Commentary |

Adrian Walker

Years later, a look at the media’s sins in the Stuart case

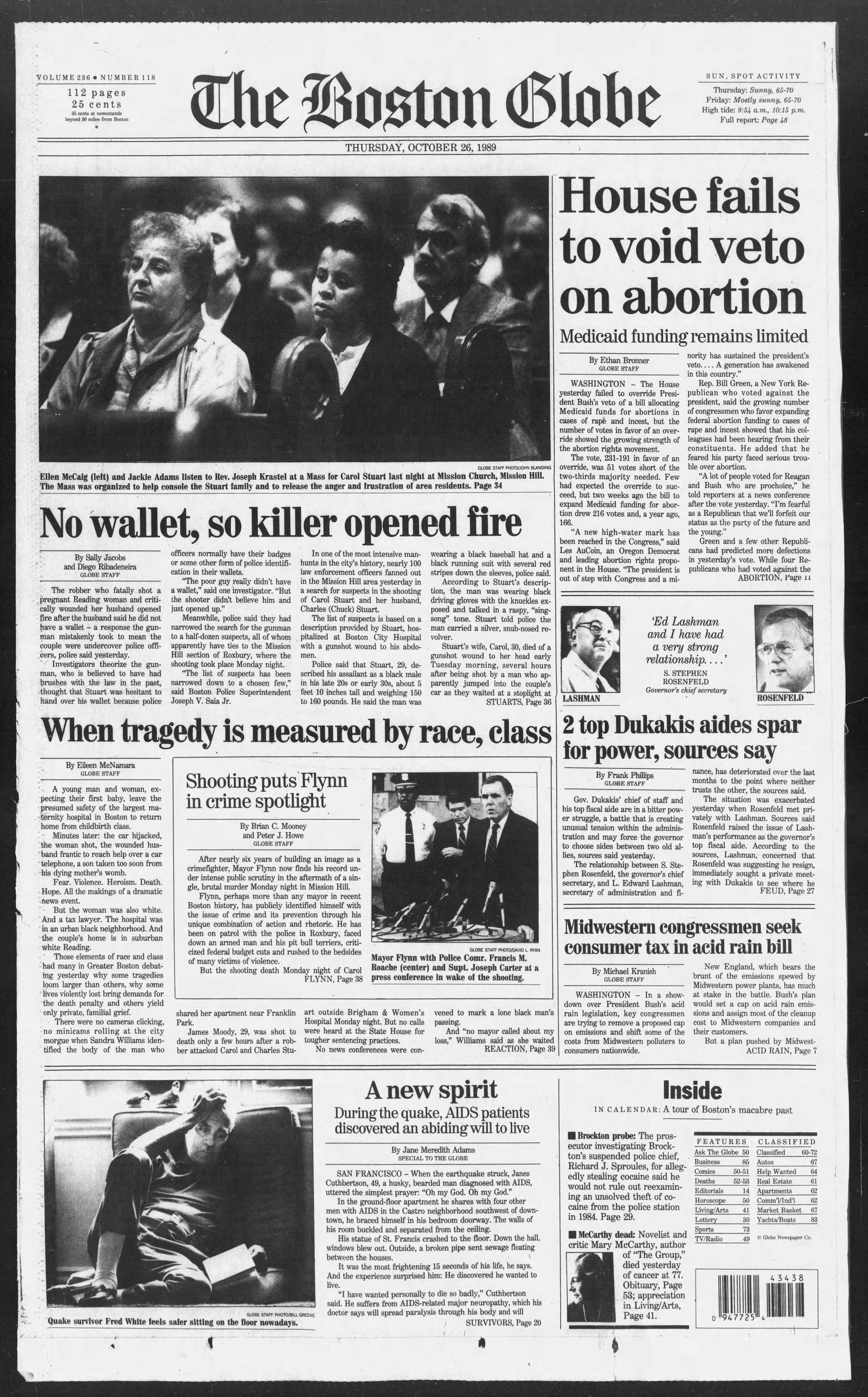

The 1989 murder of a pregnant white woman in Black-and-brown Mission Hill put the city’s longstanding race and class divisions front and center.

And it proved to be a major test for the Boston media.

It raised questions of whose murders matter, and whose stories resonate. It brought to the surface such issues as diversity — more precisely, lack of diversity — in the city’s newsrooms. And it made the city’s proud media establishment look at itself in a way that remains deeply uncomfortable to this day.

Once Charles Stuart leaped to his death off the Tobin Bridge, the city’s newsrooms came under fire for buying into his hoax — that the shooter was Black — for identifying suspects implicated by police in a murder they hadn’t committed, and for giving the killing of a white woman from the suburbs a level of attention murders of Black victims never garnered.

Most of the criticism was deserved. I say that as someone who was a reporter on the story, with a front-row seat to observe what I consider many missteps.

For a time, the case sparked an unusual spate of self-examination in the press. But the questions it raised — about how to cover communities of color and about whose stories are valued — were never resolved and resonate to this day.

So it’s time to reckon with what happened.

From the outset, this story felt different. Bigger. More dramatic.

First, there was Stuart’s 911 call, which offered a gripping moment-by-moment view of the tragedy. Some television outlets even played 13 uninterrupted minutes of the call.

Add to that a remarkable, gruesome Boston Herald snapshot of the couple bleeding out in the front seats of their car. And of course, you had the narrative of the moment: a white suburban couple set upon in the supposedly dangerous inner city.

Throw in a torrid newspaper war between the Globe and the Herald and the story was an instant sensation.

“I just knew from that moment on that everything was going to be different and this story was going to be like no other I’ve ever seen,” recalled Greg Moore, who directed the Globe’s coverage as assistant managing editor for local news.

The pressure to own the story was immense.

In the mostly white Boston media of 1989, Stuart’s bogus account wasn’t really a hard sell. Murders were way up — especially in such places as Mission Hill in Roxbury. White flight had taken root and suburbanites were anxious. There was already a sense that the city was barely under control. Maybe not even barely.

Selling Charles Stuart’s story didn’t take a mastermind. It just took someone who understood Boston — and America.

He pinned his crime on the perennial, archetypal American suspect: a Black man.

“It’s how Charles played the fault of American history,” Globe columnist Renee Graham said in an interview recently. “You know, I’m not even saying he was some sort of criminal mastermind. You don’t have to be in this country to do that. It’s been done before and it’s been done since.”

In this case, the Black man held as the lead suspect, entirely on the basis of rumor — was Willie Bennett.

Graham and I were both young Globe reporters during the Stuart case. Both outsiders — she from New York, I was from Miami. We both had plenty of questions about what was going on with the case — like, why weren’t murder charges brought against the suspects?

But in the extreme heat of that moment, our role was small; sources and contacts were the critical currency and we had neither.

The media listened to the people it leaned on as sources for every other shooting.

Which made sense. Until the morning it didn’t.

On Jan. 4, 1990, the day Stuart launched himself off the Tobin Bridge, two things were clear immediately: One was that law enforcement had gotten the story all wrong.

The other obvious fact was that a lot of coverage had badly missed the mark.

We’re talking about sins of omission, mostly. Not enough of what had emanated from City Hall, from the homicide unit, from the district attorney’s office had been aggressively challenged.

And the media was called out for those sins almost immediately — especially by a rightfully aggrieved Black community.

An odd thing happened in the immediate aftermath of Stuart’s suicide. For a while, the coverage got even more frenzied, and more irresponsible. Longstanding rules about second sources, or being careful about using anonymous sources, were cast aside.

Editors — even more concerned about getting beat — began going with almost anything that seemed plausible.

“When I go back and look at it, that was a freewheeling time,” Moore says now.

Most prominent among those who pushed the limit: Mike Barnicle, the Globe’s star Metro columnist. He broke some news, but some of the most questionable pieces bore his byline,

Barnicle had a wealth of sources within the Boston Police Department, and his own brother Paul happened to be a homicide detective. Their relationship was common knowledge in the newsroom, though seldom, if ever, shared with readers.

Barnicle hardly wrote about the Stuart shooting or the police manhunt in its first frenzied weeks. That changed once Stuart jumped.

Barnicle wrote a page one column saying Charles’s motive was a $482,000 insurance policy he’d taken out on Carol DiMaiti Stuart just weeks before her murder.

There was just one problem with that piece — it wasn’t true.

Yes, Charles and his brother Matthew Stuart plotted to profit from an insurance payout on Carol’s jewelry. But, Charles didn’t take out a big ticket life insurance policy on Carol in the weeks before her death. The insurance company, Prudential, said flatly there was no such policy and no check cut to Charles.

A Globe spokesman said at the time that the newspaper stood by its reporting, but it sure didn’t look good. When Moore, the editor, asked Barnicle about his source for the column, Barnicle simply refused to answer the question.

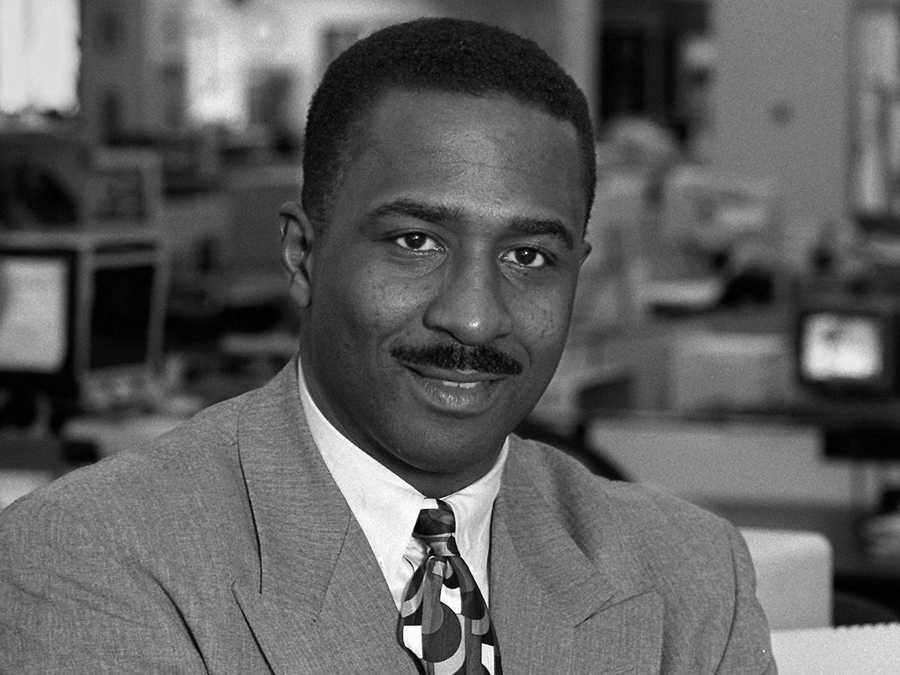

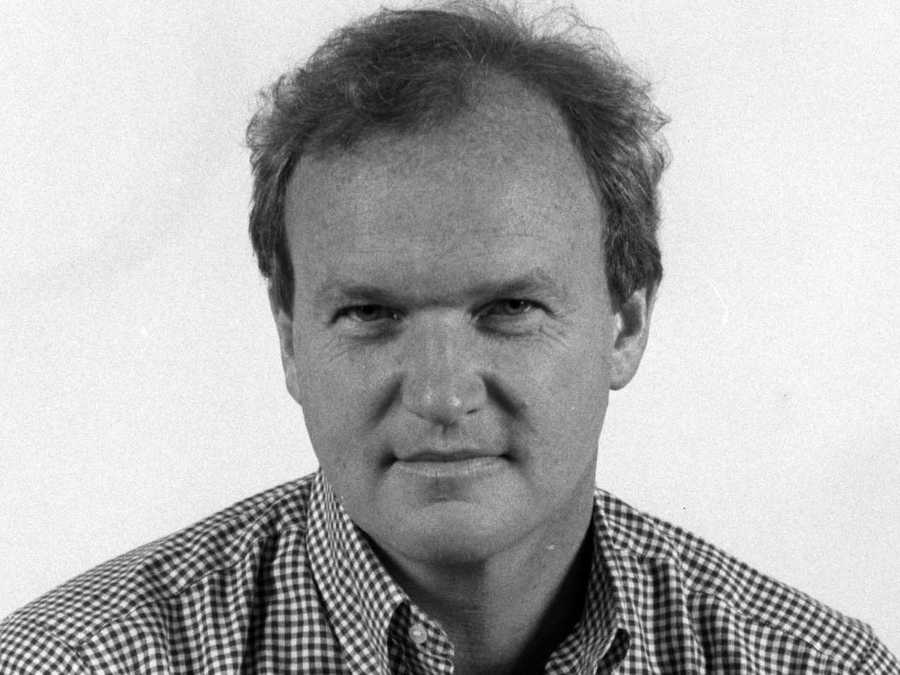

Greg Moore in 1996 and Mike Barnicle in 1989.

“And the fact that we could not force Barnicle to produce documentation for where he got that information, that was a wake-up call for me, like, you know, nobody should be bigger than an institution,” Moore recalled. “And in that case, he was.”

The Globe never published a correction.

But the Barnicle column that was even more widely criticized was one that centered on Willie Bennett’s seventh grade report card. It was published on Jan. 7, three days after Stuart jumped, and after Bennett had been cleared.

Barnicle wrote that, when Willie was a 14 year-old student, he had an extremely low IQ. And Willie got D’s in science and geography.

The column read:

“The man’s pathetic, violent history is so much a part of the unyielding issues of race, crime and drugs tearing daily at America that it is amazing how any black minister or black politician could ever stand up and howl in public that his arrest was a product of police bigotry and a volley of discrimination aimed at all black residents of Boston.”

The only reason to write such a piece, as far as I’m concerned, was to give the police cover. After they had implicated an innocent man for murder.

I called Barnicle recently and asked him to talk about his coverage. He said in so many words — no thanks. And he made it clear that he believes there’s no story here and no value in revisiting it.

For a moment, at least, the scandal prompted something uncommon in media circles: public self-reflection.

Much of that took the form of panels in which media honchos were assembled to answer for why they had performed so poorly in such a crucial moment. Some of them live today on YouTube: the legendary TV producer Fred Friendly convened one, as did the brilliant Harvard Law professor Charles Ogletree.

In those sessions, journalists bemoaned the lack of diversity in their newsrooms, conceding that they weren’t doing enough to reflect the communities they covered. At the same time, many editors and producers insisted that they had done their best with the facts at hand. Of course this murder was a bigger story than most others, they insisted. Of course the media — with no subpoena power, no ability to compel anyone to tell the truth — was at the mercy of their trusted sources.

After a few months, the panels ended. The media moved on. And the city did, too.

The questions about what had gone wrong weren’t limited to the general public. Inside the newsroom as well, the failures stung, perhaps most deeply for Black reporters who found themselves caught in the crossfire over decisions we didn’t make and couldn’t defend. Take Graham, my fellow Globe columnist, for example.

What really gets her — all these years later — is the lack of any accountability for what we got wrong.

In particular, what Barnicle got wrong. That insurance story, for instance.

“Usually you get something wrong in a story, you have to write a correction,” she said. “They never wrote a correction. And I don’t know. I always assumed it’s because they just didn’t want to make Barnicle look bad that he’d gotten something that big in the biggest story of the year wrong.”

Years later, Barnicle was caught plagiarizing, after years of being suspected of fabricating columns as well. He left the Globe in 1998. He’s now a TV columnist and contributor for MSNBC.

“That should end a career,” Graham noted. " You know, when you get tagged with the two great sins of journalism, plagiarism and fabrication, that should be the end of it. But, you know, this is America. … Life is never over for a white man in America.”

Moore, our old boss, feels differently. He said he remains proud that issues of race and class figured prominently in the Globe’s coverage from the beginning. He said he has no regrets.

That isn’t to say that he didn’t learn a painful lesson.

“In retrospect, I don’t trust anything or anybody,” Moore said. “You know, if somebody tells me something like that, I want to know exactly, what is that based on? And again, I think that’s another legacy of Stuart, at least for me.”

Moore has a point in asserting that the Globe’s coverage took on issues of race and class.

The best example might be a piece written by reporter Eileen McNamara just days after Carol Stuart’s murder.

As the Stuart story was exploding, she asked herself a simple question: Why was this murder — of all murders — the one that’s sent the city into a frenzy?

That led her to ask who else might have been murdered that evening. And she wrote a classic story about James Moody, a black man also shot to death on Oct. 23, 1989, but with none of the civic outrage that had accompanied the demise of Carol Stuart. Moody’s killing, in Dorchester, had received hardly any attention at all. As though it were simply business as usual.

Headlined, “When tragedy is measured by race, class,” the piece dove right into the sense of inequity that so many still feel about the media’s approach to crime coverage.

“James Moody, 29, was shot to death only a few hours after a robber attacked Carol and Charles Stuart outside Brigham & Women’s Hospital Monday night. But no calls were heard at the State House for tougher sentencing practices.

“No news conferences were convened to mark a lone black man’s passing.”

As Moody’s girlfriend bitterly recalled after identifying his body, “No mayor called about my loss.”

If there is anything I wish I could revisit, it would be the coverage of Willie Bennett, the man who was identified as a suspect in the Stuart murder and had his name dragged through the mud for weeks — all without ever being charged with the killing.

Bennett is now 73 and infirm, and stopped giving interviews years ago. His nephew, Joey Bennett, has emerged as his de facto spokesman.

Joey believes that the family has never been compensated for its losses and is owed for its pain and suffering.

Who wouldn’t, given what they went through?

I spent a year pursuing an interview with Joey Bennett for this project. He wanted to be paid for his story. The Globe has a hard-and-fast rule against ever paying sources to talk to us. Like most mainstream media organizations, we believe such arrangements are unethical and weaken the newspaper’s credibility with readers.

But “Murder in Boston” — the name of the documentary and podcast that parallel this Globe report — is the fruit of a partnership with HBO, and the documentary world is different. HBO and Little Room Films (the production company for the documentary) entered into what they describe as a “standard archive licensing agreement” in which Joey was paid an undisclosed sum for the use of pictures and other family materials. He then gave interviews with both HBO and the Globe, and portions of each are used in the Globe-produced podcast.

The Bennetts were conflicted in their feelings about the media. We interviewed Willie Bennett’s younger sister Veda — before Joey told his relatives to stop talking — and she was forthcoming. She said she was eager for her side of the story to be told.

I think both of those points of view — the grievance and the desire to talk — are completely valid. Indisputably, the Bennetts have been deeply wronged. Also indisputably, this story cannot be told properly without them.

Their story has always been the missing piece of this narrative.

I hope the prominence of their participation now brings the Bennetts some overdue measure of peace.

People have often asked — hell, I’ve asked — what did the media learn from the disastrous coverage of Stuart?

Graham thinks the media learned little. If anything.

“I don’t know that journalism has gotten better since the Stuart case,” she says now. “You know, I think that the media still is attracted to heat, not light. Like you always say, this is what changed everything. But it didn’t change anything. I mean, look, they couldn’t even write a damn correction, a change, nothing.”

I’m not sure I agree with that. I think we learned to be more skeptical about official stories.

And I believe this story held other lessons, whether we’ve learned them or not.

It was a lesson on why newsrooms need to reflect the people whose stories are being told. Also we need to be more skeptical about accepting the accounts of those in power.

We learned — or should have learned — that we needed to talk to more people in places like Mission Hill, to people bearing the brunt of the decisions of people in power. As we all know, abuses of power hardly ended in 1989.

I hope we learned how to think more broadly about who suffers in the wake of crime. In 1989, our understanding of the victims began and ended with the two families: the Stuarts and the DiMaitis.

But an entire neighborhood suffered as well. We hear their voices now: those of DonJuan Moses, Ron Bell, Tito Jackson, and so many others.

We needed to hear them then.

And we didn’t.

Adrian Walker is a Globe columnist. He can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him @Adrian_Walker.

Update: This piece was updated to reflect that Mike Barnicle claimed in a copyrighted Globe column that Charles Stuart’s motive was a $482,000 insurance policy Stuart had taken out on Carol DiMaiti Stuart just weeks before her murder. The insurance policy didn’t exist. Material from that column was also used in a corresponding news story, which included Barnicle’s byline, among others.

Advertisement