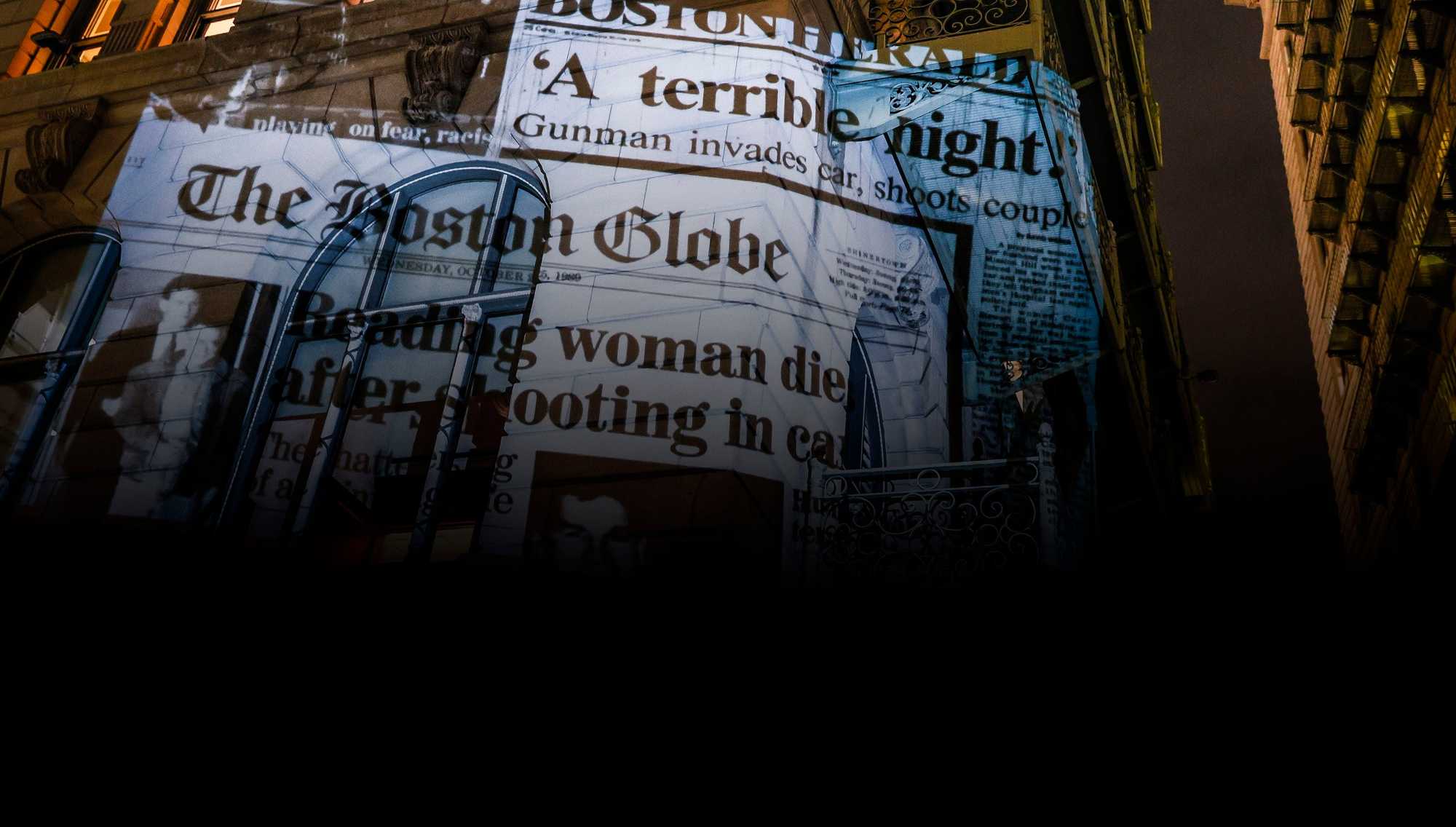

The Charles Stuart Case:

Chapter 8

New clues challenge the long-held narrative. It may be too late for many.

Autoplay audio

Veda Bennett opened her front door to two strangers one summer morning in 2022.

Her Mission Hill apartment was dark and cool and still — a sharp contrast from the sweltering concrete patio where she liked to sit on a milk crate and chat with her neighbors. People called her Channel One, because she knew all the good gossip.

“I’m glad y’all came,” Veda said. She meant it.

She thought this conversation might hurt, but she also knew it had to be done. So, she stepped back from the door and gestured — come inside — and two Globe reporters stepped across 33 years of silence and into her kitchen.

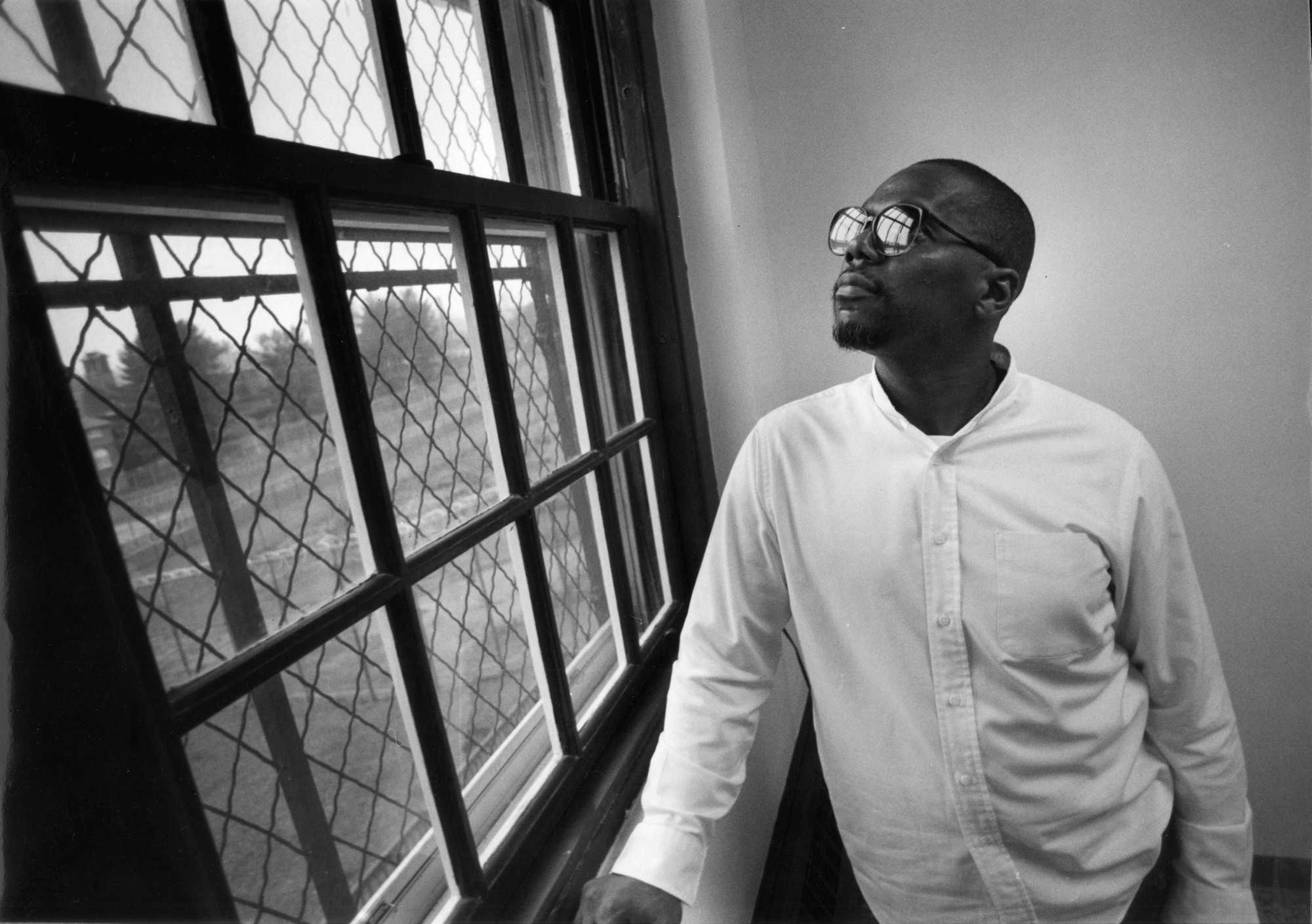

They settled at the kitchen table, and before anyone asked a single question, Willie Bennett’s younger sister started to talk.

“Nobody ever heard my story,” Veda began, and she slipped back into the fall of 1989, a time that Veda never really left. The Stuart case sucked her in and never let her go, like a planet forever orbiting the sun.

“For people to say it’s over with, it’s over with? It’s never gonna be over with for Veda Bennett,” she said, sitting underneath pictures of Willie and her dead mother and the old Mission Hill apartment where they were all living together when the police barged in and tore everything apart.

“It’s never over. It’s never gonna be over. It’s never gonna be over.”

Though the city, the police, the media — everyone, really — considers this case long closed, Veda said they’re all wrong. “They can say that,” she said, “because it didn’t happen to them.”

Mission Hill looks much different than on the night of Oct. 23, 1989, when Chuck Stuart called 911 and said that a Black man had jumped into his car and shot him and his pregnant wife, Carol. That call sparked a manhunt that swept up an untold number of Black men before police zeroed in on Veda’s brother Willie, a notorious criminal who had, as it soon became clear, nothing to do with this crime.

In the years that followed, the city tore the old brick public housing buildings down and rebuilt them in soothing baby blues and cream. Alton Court, where Willie lived at the time of his arrest, is gone, and some view this as erasure instead of progress.

The city relocated Veda Bennett to a new unit, where she said she wakes up every night at 2:30 a.m. to the sound seared in her memory, of her door opening and the police storming inside. At night, Veda said, it’s always the hour of the raid. Veda is always 29 years old, holding her 7-year-old niece on her hip as the police push through her home. She is always terrified and tripping as she runs, tumbling down the stairs, hitting her head.

She has a tumor in her head now, and she swears it was that tumble that caused it. When she does sleep, she dreams about the Stuart case. “It’s never going out of my head,” she said with a short, dark laugh. “It’s right next to the tumor.”

Every Bennett since Willie has battled with the legacy of the Stuart case. It’s a festering wound at the center of their family’s story. After the truth came out — that there never was any Black man, that Willie was innocent, that Chuck killed his own wife and child — the Bennett family never got a public apology. The Boston police never admitted they did anything wrong. The media didn’t run any corrections to its journalism.

The Bennetts sued the city in federal and state courts, but years of litigation netted them just $12,500 — a sum they collectively viewed as more insulting than zero. Willie’s mother, Pauline, used some of the money to buy new church clothes from a discount magazine and died a few months later, bitter to the end.

Veda remembers her mother’s last moments. It was the middle of the night, and Veda said she heard a thump, then Pauline calling out: I can’t breathe ... that Stuart case, that Stuart case. And then she was gone.

After Chuck jumped, there were investigations and trials and commissions and reports. The lead homicide detective who pursued Willie as the suspect got a five-day suspension, which was knocked down to four, then knocked down to three, and then tossed altogether on appeal.

Chuck’s brother Matthew and his friend went to prison for three years for getting rid of the gun. The Bennetts got their $12,500. And then, people did what Mayor Ray Flynn had been asking all along: They stopped thinking about the past. They moved forward.

But enormous questions — both evidentiary and moral — were left unanswered. The Bennetts and a whole lot of other people in Mission Hill and beyond were left behind. For them, there’s never been anything that resembles justice.

The Globe spent two years reinvestigating the Stuart murder case, from the crime to the aftermath to the influence it has on the city today.

A team of reporters conducted hundreds of interviews, and traveled thousands of miles to talk to key players. Reporters hunted through archives and basements and the back rooms of courthouses to reassemble as much of the original casefile as they could — including secret grand jury transcripts and audio recordings of interrogations that have sat unplayed on decaying tape cassettes.

Taken together, the material significantly changes the long-held narrative around the case. The Globe team found:

- Boston police didn’t just miss the clues that Chuck was likely behind the murder, they ignored them.

- A sprawling whisper network of people on the North Shore knew the truth about Chuck, and chose not to go to the police. Dozens knew he was behind Carol’s killing — some for months — but said nothing.

- Several doctors believe it’s implausible that Chuck shot himself, a key finding that suggests someone else may have pulled the trigger.

- And evidence points to Chuck’s brother, Matthew, playing a much larger role in the shooting than previously known, running counter to his claims he was tricked into helping get rid of the murder weapon.

It’s too late for any of this to matter to Willie. He’s still alive, suffering from dementia and living alone in Boston. He declined, through a family spokesperson, to comment.

And maybe it’s too late for Veda, too. “We’re not gonna gain nothing, we’re not gonna win nothing,” she said to the reporters who visited her that summer.

But maybe the simple act of breaking the silence will help.

“Somebody’s listening to me, you know?” Veda said. “Finally. Somebody’s listening.”

In the early 1990s, as the dust settled on all things Stuart, the Boston Police Department sought to figure out how its detectives landed where they did, and whether officers broke any rules or laws in the quest for the killer. When the head of the homicide unit, Lieutenant Detective Edward McNelley, sat down with internal affairs investigators, he was steadfast that his officers had done nothing wrong.

“In my opinion, the investigation was properly conducted. I think it was done competently. I think it was done professionally. I do not think there was any wrongdoing,” McNelley said. “Did he [Charles Stuart] fool us? Yes, he fooled us. But other than that, I do not find any fault with that investigation.”

The department agreed. Other than lead detective Peter O’Malley’s swearing at a witness and a “joke” about using officer Billy Dunn as a “lie detector test,” the Police Department’s internal affairs unit found that officers did everything by the book.

Chuck Stuart just fooled ‘em.

But this is far from the truth.

The first two detectives assigned to the case, Robert Ahearn and Robert Tinlin — “the two Bobbies” — suspected from the get-go that Chuck might be the killer. But they were sidelined, and O’Malley was brought in to pursue Willie. Ahearn testified in 1991 before a federal grand jury that he told both McNelley and O’Malley of his suspicions about Chuck.

This failure to pursue Chuck as a suspect was not the only chance the department missed.

Beginning in October of 1989, just days after the shootings, two men close to Chuck Stuart’s inner circle began reaching out to different police officers in Massachusetts, trying to pass along a tip that Chuck was the killer, according to police reports and grand jury testimony obtained by the Globe.

The two men were Michael “Dennis” MacLean and John Carlson. Dennis was the brother of David MacLean, Chuck’s best friend from high school. And John was Dennis’s pal. John was unavailable for an interview and Dennis declined.

Back in late 1989, shortly after Carol’s funeral, Dennis MacLean’s brother told him that Chuck had confided in him about the murder. Dennis told John, and the men decided to call police, according to Dennis’s grand jury testimony.

They were nervous, so they chose not to call the Boston police tip line directly. Instead, sometime around Nov. 1, before police had made the turn to Willie as the prime suspect, Dennis and John reached out to Sergeant Dan Grabowski, a state trooper John knew.

“He called him, gave him the information,” Dennis testified. “That it was Chuck that killed his wife.”

Grabowski took the information, Dennis said, but he never called back. No one did.

The Globe reached out to Grabowski for comment, and he declined in a voicemail and text messages to be interviewed.

“I know what’s going to happen. You’re going to make Willie Bennett a hero just like they made George Floyd a hero,” Grabowski said in the voicemail to a Globe reporter. “A complete piece of shit, a piece of trash that terrorized people his whole life.”

00:00

00:00

Grabowski retired from the Massachusetts State Police a few years ago, after rising to the rank of major, one of the highest in the organization.

For nearly a year, he sent profane and racist text messages to a Globe reporter, suggesting the media was complicit in a grand conspiracy to hide the truth.

Dennis MacLean and John Carlson didn’t give up after Grabowski blew them off. In the middle of November, they contacted another police officer who happened to be John’s brother-in-law, according to grand jury testimony. That officer took their tip more seriously.

On Nov. 16, a few days after Willie was arrested, the officer passed the tip along to Ahearn, one of the original detectives on the case.

This was the moment when the investigation into Willie could have come screeching to a halt. This was a credible tip, passed along by a police officer who vouched for one of the tipsters.

Ahearn himself already believed Chuck was the murderer.

So it’s hard, in hindsight, to understand what happened next:

Nothing.

On Nov. 18, Ahearn called David MacLean, whom Chuck had asked to help kill Carol. But David said he didn’t know anything and didn’t want to talk, then he hung up the phone.

And that ... was it.

No police car squealed to a stop in front of his house with its siren blaring. No sledgehammer banged his door down. Ahearn didn’t even call him back.

Two longtime Boston police officers — one current, one former — speculated that Ahearn could have been bitter about losing the case to O’Malley. If O’Malley wanted Ahearn’s case, he could hang himself with it.

Ahearn died in 2017. His partner, Tinlin, died in 2001. Ahearn did tell the grand jury in 1991 that he regretted not doing more.

And Tinlin’s son, who grew up to be a police officer too, said the case gnawed at the two Bobbies for the rest of their lives.

But whatever Ahearn’s motivation — department rivalry, apathy, exhaustion — the single best tip the Boston police had to solve the Stuart murder got shoved into a drawer and forgotten.

The story of the Stuart case holds that much of the world was shocked when the truth came out that Chuck was the real killer.

On Boston’s North Shore, it was old news.

The Globe found — through an analysis based on police files, grand jury testimony, recorded phone calls, and more — that at least 33 people knew the truth by the time Matthew went to police with his story on Jan. 3, 1990.

Thirty-three people knew that — as Matthew Stuart said to Michael Stuart three days after the murder — “There’s no Black person that did this.”

And yet, almost every one of those people stayed quiet, even as Chuck identified in a lineup a man they knew to be innocent.

Much like the rumor about Willie Bennett shared by a few teens in a Mission Hill smoke session, this, too, was a perverse game of telephone. Siblings told friends, who told friends, who kept it secret.

In Mission Hill, an 18-year-old Black man told his mother, who told a detective.

But in Revere, a type of omerta took hold among some Stuarts, their friends, and friends of friends. They talked — just not to police.

The Stuart case is not just a story about institutional failures by police, politicians, and the media. It is a story about the failures of regular people, too. People who believed themselves to be good and moral and decent who watched something terrible happen and did nothing.

The Globe reached out to every person who knew the truth before the police. None of them agreed to speak.

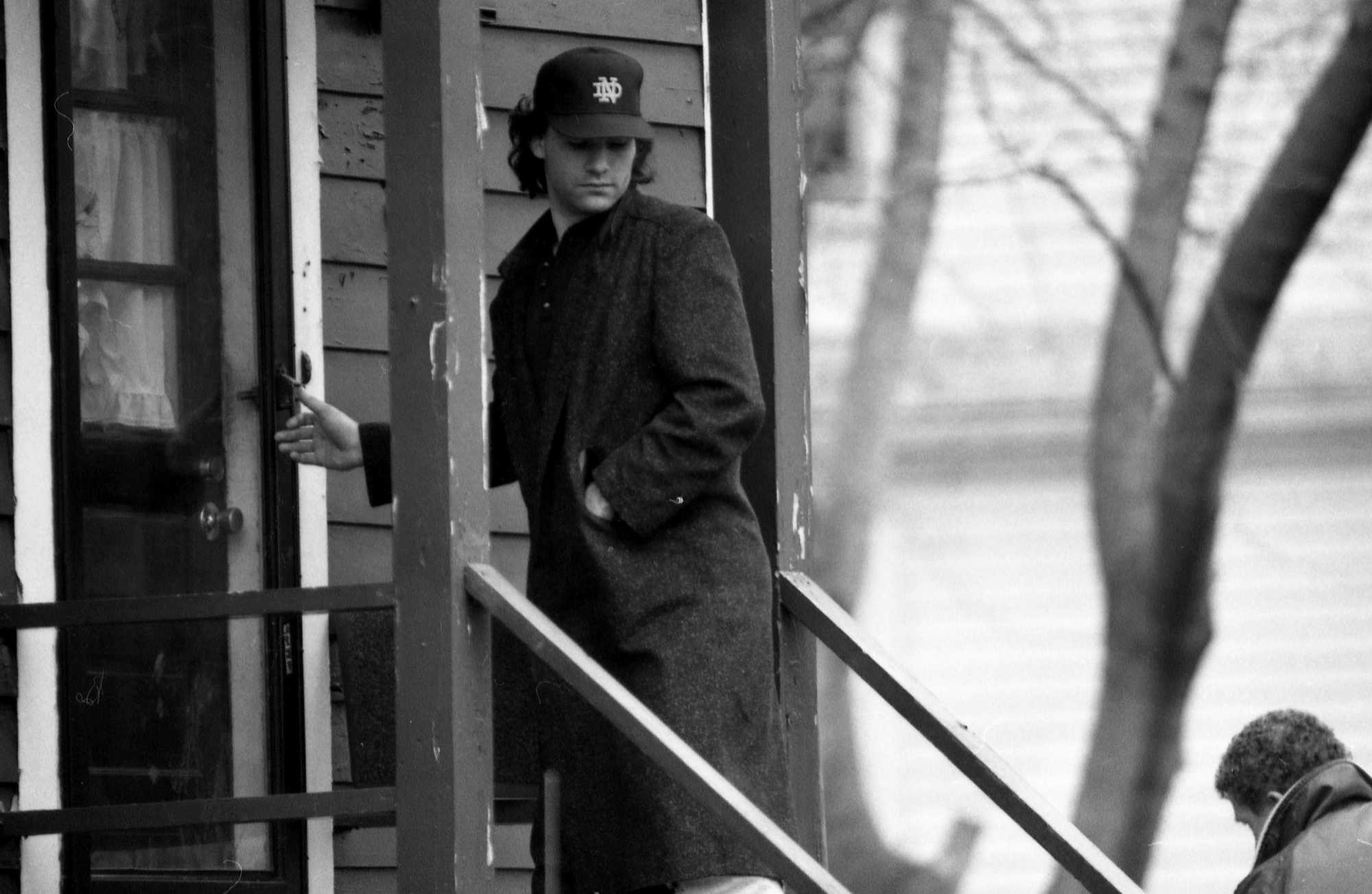

When Matthew Stuart confessed to Boston police that he disposed of the gun after Chuck killed Carol, he was motivated in part by the fear that Chuck would go to the cops first and blame Matthew for everything, his brother Michael later told police.

But Matthew didn’t have to worry. Chuck jumped and Matthew stuck to the story he told police for the rest of his life: That he never knew Chuck planned to kill Carol, and he wasn’t there when it happened. That he never even saw Carol in the car with Chuck the night of the shooting. That he had no idea Chuck even had a gun — until after Carol was dead.

In the years since the murder, a lot of people have come to view Matthew as one of the good guys.

“Matthew Stuart was one of the few heroes of this,” said Jack Harper, the WCVB-TV reporter reporter who covered the case and stood by the Mystic River on the morning of Chuck’s suicide. “If you give him the benefit of the doubt, he was the brother who went along with it initially, got rid of the gun and the stolen stuff, but at least he had a conscience down the road. … He finally said something. … He had the stones to go talk.”

Nancy Gertner, Matthew’s attorney, has always believed that Matthew was a victim of his older brother’s machinations and that Matthew bravely came forward to do the right thing and was punished for it with jail time.

“This was a young man who was tortured by this, and was actually seeking help from every quarter he could get,” said Gertner, who later became a federal judge. “Charles was the golden boy in the family. So here [Matthew] was saying something unbelievable about his older brother, saying something that was going to lead to his older brother being in prison for the rest of his life.”

00:00

00:00

The official story of the Stuart murder case is that Chuck acted alone.

But the Globe pulled medical records, police forensic reports, FBI lab notes, and more, and there is strong evidence someone else was there that night helping Chuck. And that person may have pulled the trigger.

The first clues come from detailed accounts of three witnesses who each told police that they saw a third person in or near the car with Chuck and Carol on the night of the killing. Their statements were tucked among thousands of pages of police and legal documents and have never been reported before.

The first was a basketball coach who was standing on the steps of the Tobin Center on Tremont Street, waiting for his players to arrive. Chuck’s route would have taken him past the Tobin on the way to the side street where Carol was most likely killed.

The basketball coach told police he saw a dark blue car, which matched the description of Chuck’s Cressida, driving erratically down Tremont, with a white man behind the wheel. He assumed it was a drunk driver. But what stuck out as particularly strange was what he saw in the back seat: a man in the middle, hunched over.

The second was a woman who lived in an apartment building overlooking the spot on St. Alphonsus Street where police found Chuck’s car. She told police she was leaning out her window to water her flowers when she heard a car door slam, and then saw a stocky man with a full head of hair running away from the car, saying “Oh my god, you [expletive].” The man she described resembled Matthew.

A few minutes later, she heard sirens and police, and when she looked out, she saw emergency workers taking Chuck and Carol out of the same car.

And the third witness was a man driving around the neighborhood, who told police and prosecutors that he saw a car with its headlights off park on St. Alphonsus Street. He circled, and when he passed it a second time, he saw a white man in the driver’s seat and another man whose face he couldn’t see getting out of the back seat. When he passed the car a third time, he saw the police and ambulances surrounding it.

The Globe can’t ask the witnesses about what they saw because all three are dead.

In addition to these witness statements, more clues were found in ballistics reports.

There’s no dispute that three bullets were fired in Chuck’s and Carol’s car. One entered the back of Carol’s head; police found a second lodged in the ceiling; and the third left a wound in Chuck’s lower back, traveling upward through his liver and intestines.

Dr. Erwin Hirsch, the Boston trauma surgeon who operated on Chuck that night, had treated hundreds if not thousands of gunshot wounds in Vietnam. And he was adamant that Chuck could not have shot himself. It was his view that led police to believe that Chuck was an innocent victim.

Hirsch is dead. But two other doctors who also operated on Chuck are alive, and both of them told the Globe they agreed with Hirsch: It didn’t make sense that Chuck shot himself.

At Hirsch’s direction, Dr. Fred Millham acted as Chuck’s personal doctor. Millham not only examined Chuck’s guts, he also spent a lot of time around Chuck and his family while Chuck was recovering. And during those visits, Millham picked up odd vibes. In a recent interview, Millham cited patient confidentiality laws that prevent him from saying anything specific. But given everything he saw back then, he said, he is confident in his assessment.

“It’s my opinion based on facts that everybody has — I think the brother probably did the shooting. But I’ve always thought that, since I saw them dragging Charles’s body out of the harbor,” Millham said.

“It was Matthew. Of course.”

These clues, together with the fact that Matthew admitted to conspiring with Chuck, being in Mission Hill at the time of the shooting, disposing of the gun, then covering it up for two and a half months — they suggest there’s much more to Matthew’s story than what he told police.

The lead prosecutor on the case thought so.

Francis O’Meara, the head of the homicide unit at the Suffolk district attorney’s office, testified under oath in 1991 that he was certain there was someone else in the car for the shooting — and that it could only be one of two people.

“There’s no question in my mind, none whatsoever, that there was a third person on St. Alphonsus Street that night, and it’s either Matthew Stuart or Willie Bennett,” O’Meara said. “There’s absolutely no question in my mind.”

If the lead prosecutor was so sure, why wasn’t Matthew ever charged in the murder?

O’Meara retired a long time ago. In late 2022, O’Meara wasn’t interested in talking to Globe reporters. He said it was better to let sleeping dogs lie. He died a few months later.

Matthew’s attorney, Gertner, said the reason Matthew wasn’t charged was simple: He was innocent. She pointed out that a grand jury tried to prove Matthew was involved in the murder — they interviewed nearly 100 people and pored over the case for years.

“I mean, if there had been a whisper of that evidence, he would have been charged with being an accessory to murder,” Gertner said. “And that was not a charge that they could bring.”

Matthew died of a drug overdose in a homeless shelter in 2011. His accomplice in ditching the gun, Jack McMahon, didn’t respond to numerous requests for comment.

Finally, the Globe reached out to an independent forensic consultant, Lewis Gordon, and shared with him all the police and FBI files on the shooting as well as the autopsy reports and other material. But Gordon couldn’t provide a definitive determination.

“He certainly could have shot himself. He certainly could have been shot by someone else,” Gordon said. “We just don’t have enough information to reach a conclusion one one way or the other.”

With the passage of time, there may be no way to say for sure.

Like everything else in Mission Hill, the block where the shooting took place is vastly different now. Back in ‘89, it was a bleak dead end with an abandoned bar on the corner. But on an afternoon last summer, it was buzzing with construction workers building condos where the old bar once was.

Globe reporters flagged one of them down, a young Black man named Rashard Young, and asked if he’d ever heard of the murder that unfolded right where he was standing. He squinted in confusion, until someone said, “Chuck Stuart?”

His eyes slowly lit with recognition. Then he tried to explain the thread that tied his life to Stuart’s crime.

“I was told that it wasn’t — it’s not what we think it was,” Rashard said, working it out.

Rashard knew the outlines of the story — a white man killed his wife and blamed a Black man, and the police and everybody else believed him.

Rashard wasn’t even born then, but he knows the story because his older brother told it to him when he was still a kid. In his family, the Stuart case was a warning.

“He was like, ‘Get used to it,’ you know?” Rashard said of his brother. “It was just like, Wow. Like, we can be lied on like that so quick. That’s what really scared me. You know, I’ve been lied on too… you know. So I definitely know what it’s like just because of my complexion and my just — who I am.”

Rashard’s dad is Black and his mom is white. He said he’s always felt torn between the two. But the outside world isn’t confused at all. His blackness is what people see. It’s what the police see, too.

“When they got that badge on, it’s their world,” Rashard said. “You’re living in their world.”

All these years later. Same spot. Same neighborhood. Same fear.

In the wake of the Stuart case, there were lots of recommendations about how to fix the problems in the Police Department, but many never came to fruition.

From federal authorities to the state attorney general’s office, officials determined police had done disturbing things, including stripping Black boys and men in public and searching them. The detective work was shoddy, and the teenage witnesses were scared. But each of these agencies stopped short of calling anything illegal.

Wayne Budd, the US attorney for Massachusetts at the time, wrote a scorching report on the department’s actions. As a Black man, Budd felt enormous pressure to hold someone accountable. But he couldn’t prove that the police violated federal civil rights laws. He didn’t charge anyone. And the blowback from police critics was brutal.

“The reaction from the community was particularly stinging,” he told the Globe. Budd said people told him: “Nobody’s doing anything about what these cops did in our community. You’re the US attorney, Wayne Budd, and you’re our last hope in getting justice from this.”

Budd went on to become US associate attorney general, and he oversaw the federal prosecution of the Los Angeles police officers who beat a Black man named Rodney King.

In 2020, with America up in arms again over racism and police abuse, the Boston police again came under the microscope. A team of Globe reporters — including some involved in this story — exposed corruption and misconduct within the department, as well as several instances of the agency’s failure to deliver on past pledges of reform.

Amid all this, the city again turned to Wayne Budd.

Budd chaired a commission that came up with a slate of Boston police reforms. Some of them resembled recommendations that came out of a commission formed following the Stuart case. The department is still working on some of those changes.

Today, Boston has more work to do, but this much is clear: It is not the city it was in 1989.

In 2021, voters elected for the first time a mayor who was not a white male. Michelle Wu — the 38-year-old daughter of Taiwanese immigrants, who ran on a progressive agenda that included platforms on rent control and free public transportation — won in a landslide.

Quickly, Wu made a statement with her choice for police commissioner: a former Boston police officer named Michael Cox.

And Michael Cox — he has quite a backstory.

At the time of the Stuart shooting, he was a new cop, and one of the only Black officers working drugs. One night, while Cox was undercover, fellow Boston officers mistook him for a drug dealer and viciously beat him. It took Cox years to heal.

But Cox didn’t leave the department. He stayed on the force and rose through the ranks, before leaving a few years ago to serve as a chief of police in Michigan.

His return to Boston as commissioner has been widely viewed as the best hope for ushering in a new era for the BPD.

What Cox does with that power remains to be seen. He declined to be interviewed for this project.

The scars of the Stuart case may not be so visible across Boston today, at least not on the surface.

But it lives in the homes of Black and brown families, where older brothers pass on tips to boys who will one day grow up to become construction workers and help build condos on the land where a man named Charles Stuart once called 911 to say he and wife were shot.

It’s a lesson, if you’re looking. But it doesn’t have to be a lesson that is only about the terrible things people do to each other, and the way people fail to live up to their ideals.

Take, for example, the 6-foot, 5-inch Black man with a giant smile who comes home to Mission Hill every so often to buy custom hats in bulk. The ball caps are black, with the word “LOVE” in red letters.

The man’s name is DonJuan Moses. He was the 11-year-old boy watching his family play cards in their Mission Hill apartment back in ‘89, when the police barged in and took his cousin away because he matched Chuck’s description. Black man.

DonJuan’s fear of the police has never left him. He keeps a dashcam on his windshield, backed up to his hard drive, because he’s afraid of what may happen if he gets pulled over. His trauma doesn’t come from the Stuart case alone — his father spent 41 years in prison for murder, until he was exonerated and freed in 2020.

But out of all this fear and anger, DonJuan has found something beautiful.

DonJuan buys the LOVE hats because he works in a hospice, and he likes to give the hats to the patients. He wants them to know that, even if they have no family, they’re not going to die alone. He will be there.

“Give them what you ain’t never had. Love,” he said. “Give them something that we are not promised.”

This type of love — joy, even — was evident on a cold winter night in 2022, a mile or so from that once-bleak corner where Carol and Christopher Stuart were killed.

A group of Black and Latino high school students trickled through the door of a meeting room, where their mentor, George “Chip” Greenidge Jr., waited for them.

Chip knows Mission Hill. His dad has lived there since the 1980s. When the shooting happened, Chip watched his neighborhood convulse. When the police swept through, Chip’s dad banned him from visiting.

So he watched it unfold on TV, with everybody else.

A world away, Carol’s family, the DiMaitis, were watching, too.

And their reaction to the crime would change the course of Chip’s life.

After the DiMaitis lost their daughter and grandson in such a horrifying, public way, they didn’t want to keep talking about the awful things done in Carol’s and Christopher’s names.

They did want a way to remember them. They wanted Carol’s legacy to be about something other than her husband’s terrible crime.

So a few weeks after Chuck’s suicide, Carol’s family announced the creation of a foundation, the Carol DiMaiti Stuart Foundation, that would grant college scholarships to the residents of Mission Hill and promote better race relationships throughout Boston.

“There has been so much said and written about this terrible tragedy in our lives that we don’t want to add to that today,” said Carol’s father, Giusto. “Carol was a loving, caring person who always thought of the other person first. She loved to help those less fortunate than herself and was constantly trying to improve their place in this world.”

00:00

00:00

Over the next month, the foundation garnered more than $270,000 in donations. The letters and support poured in from across the country. Vice President Dan Quayle sent $150, as did Massachusetts Congressman Barney Frank. Governor Michael Dukakis donated $50, along with a lunch invite.

And soon, the foundation put that money to use.

One of its first scholarship recipients was a young man named Chip.

Chip remembers one day, when all the scholars the foundation had sponsored came together. Carol’s mother and father were there, and Chip remembers the way her mother Evelyn hugged him so tight, smiling so hard.

“She was proud to call us her kids,” Chip said. “She was very proud that this scholarship fund was a way to have the wonderful legacy of her daughter and her grandson to live on.”

Of all the many victims of the Stuart murder case, none suffered more personal or devastating losses than the DiMaiti family.

Yet it was the DiMaitis — not City Hall, and certainly not the Police Department — who sought to build bridges.

Their foundation helped Chip pay for tuition at Morehouse College. These days, he’s finishing a PhD at Georgia State University, and he’s a visiting fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School.

And in early 2023, Wu appointed him to Boston’s Reparations Task Force, where he will help examine the wrongs that the city has done to Black residents.

“The push was that we would always give back to the neighborhood of Mission Hill and Roxbury,” he told the Globe. “And that’s what I’ve done. Always.”

Chip is a busy guy. On that cold winter night in 2022, he obliged two reporters who asked for an interview, but then his students started badgering him and joking and laughing and generally being teenagers. Finally, he had to stop talking and focus on them.

“How’s everyone doing today? How’s everyone doing today!?” Chip bellowed, clapping his hands and grinning as the kids met his goofy greeting with their own. “Good, good, good, good.”

Then he introduced the reporters.

“This is the Boston Globe right here,” he said. “Anyone ever hear of Charles Stuart before?”

The kids all just stared at him.

“Anyone heard of Carol Stuart before?” he tried again, and this time the kids said no, together.

00:00

00:00

“Everybody? No? Not at all?” Chip said. “OK. Well, we’re going to get our session started.”

For 34 years, Chuck Stuart and all the trauma he sowed have served as a mark against the city, a slice of history that’s been impossible to move past.

Racial divisions haven’t disappeared. But this is also not the same city that fell for Chuck’s hoax.

That was plainly apparent in the warm meeting room, where Chip Greenidge was helping a group of Black and Latino teens write their college essays.

These teens haven’t forgotten the nightmare in Mission Hill. They don’t know that history at all.

Which means they don’t have to live with it, either.

So they’re free, to put pens to paper, and set off to write the next chapter of Boston’s story.

About this story

To report “Nightmare in Mission Hill,” Globe journalists spent thousands of hours, over two years, examining documents, photographs, audio recordings, and video. The team conducted more than 250 interviews.

Quotes within this story were either taken directly from sworn testimony, police interviews, audiotapes, or were heard by reporters. In cases where someone recounted dialogue or comments, those words appear in italics.

Click here for more information on sourcing.

Advertisement