The Charles Stuart Case:

Chapter 7

A city asks: How could we not have known?

Autoplay audio

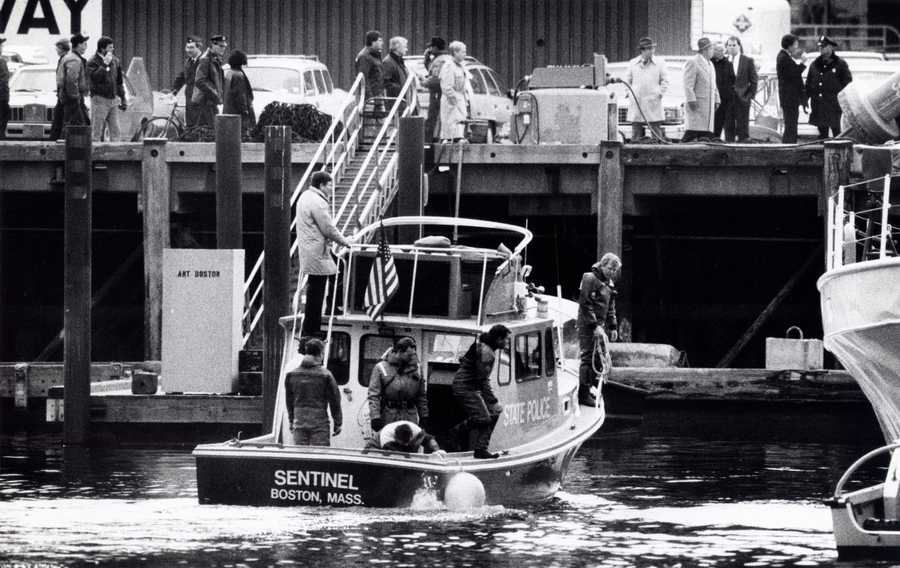

Jack Harper stood on a dock and watched State Police divers bob in the choppy waters of the Mystic River. It was the morning of Jan. 4, 1990, and all the WCVB-TV reporter knew was that a man had jumped off the Tobin Bridge just before sunrise. Police were saying it was Chuck Stuart, the man who had dominated headlines for months.

This poor guy, Jack thought.

Jack had watched Carol Stuart’s funeral on TV with the rest of America. He’d even cried at Chuck’s eulogy: Goodnight, sweet wife, my love, Chuck had written for a friend to read aloud. God has called you to his hands.

From his hospital bed, Chuck had drawn from some impossible well of compassion and urged the people of Boston to forgive his wife’s killer. Jack, like many others, felt sympathy.

Now, police boats circled the divers in the Mystic and helicopters buzzed in the sky. The bridge and the dock swarmed with police, grimacing men in long trench coats barking into handheld radios and trying to steer clear of the media horde.

Law enforcement officials would only say that they were looking for Chuck. They had said nothing about Chuck’s brother coming forward overnight to reveal Chuck as the mastermind behind his pregnant wife’s and son’s killing.

So Jack — along with countless others watching the events unfold on TV that morning — assumed that Chuck had finally buckled under the weight of his losses.

A State Police diver searched for Chuck Stuart's body on Jan. 4, 1990. (David L. Ryan/Globe Staff)

What a terrible ending, Jack recalled thinking to himself. He just couldn’t take it anymore. I understand.

Nearby, Jack caught sight of the first assistant district attorney, a taciturn but nice enough guy. Jack walked over.

Oh my god, Jack said to him. How much worse can it get?

Jack wasn’t fishing for information. He recalled that the prosecutor wouldn’t tell a reporter if their pants were on fire. Jack was just talking to talk, because he couldn’t watch all of this in silence.

He’ll never forget what happened next.

The prosecutor looked at him and said: You have no idea. You don’t know what happened.

There was a pause, while Jack tried to make sense of what the prosecutor was saying. It didn’t compute.

It’s not what you think, Jack remembers the prosecutor saying. He killed her. He set this up. He just committed suicide.

The wind blew. The boats waited, the cops waited, the city waited, the country waited, for Chuck’s body to rise up to the surface of the water. For somebody to finally see him.

Jack’s mind went blank.

Everything had changed.

The police theories, the media narratives, the citizen outrage. It was all wrong.

Suddenly, it was like the whole world was looking down into the water where Chuck Stuart went under, and seeing themselves in the reflection.

And it was ugly.

Carol’s friend remembers collapsing in hysterical sobbing when she heard the news. Barbara Williamson was shocked, of course, but almost worse than that, she was sick with guilt.

How could we not have figured this out? she wondered. How could we not have known?

Barbara had worked with Carol at the accounting firm, and she knew Chuck through Carol’s eyes: romantic, handsome, quiet, kind. Never once in the last two and a half months did she question his innocence. Never once did she question his story: that a Black man robbed and shot him and Carol.

Now, Barbara sank into the arms of a friend, and tried to find the courage to look at herself with this sharp new clarity. She felt a deep and painful shame.

00:00

00:00

I was a part of it, she remembers thinking. I was complicit. No, I didn’t pull the trigger. No, I didn’t point the finger at the wrong guy. But I’m white. And I’m enmeshed in this.

Barbara was right.

Everyone was enmeshed in this.

It only took two words from Chuck, as he lay bleeding on a stretcher in the back of an ambulance: Black. Man.

And all the machinery — the police, the press, the politicians — kicked into gear to do what they always had done. Find the Black man.

Chuck didn’t pull off his racist hoax alone. He had everyone’s help.

When Chuck jumped and the truth was revealed, a huge swath of Boston was left to reckon with the knowledge that knocked Barbara Williamson to her knees:

That they were exactly who Chuck thought they were.

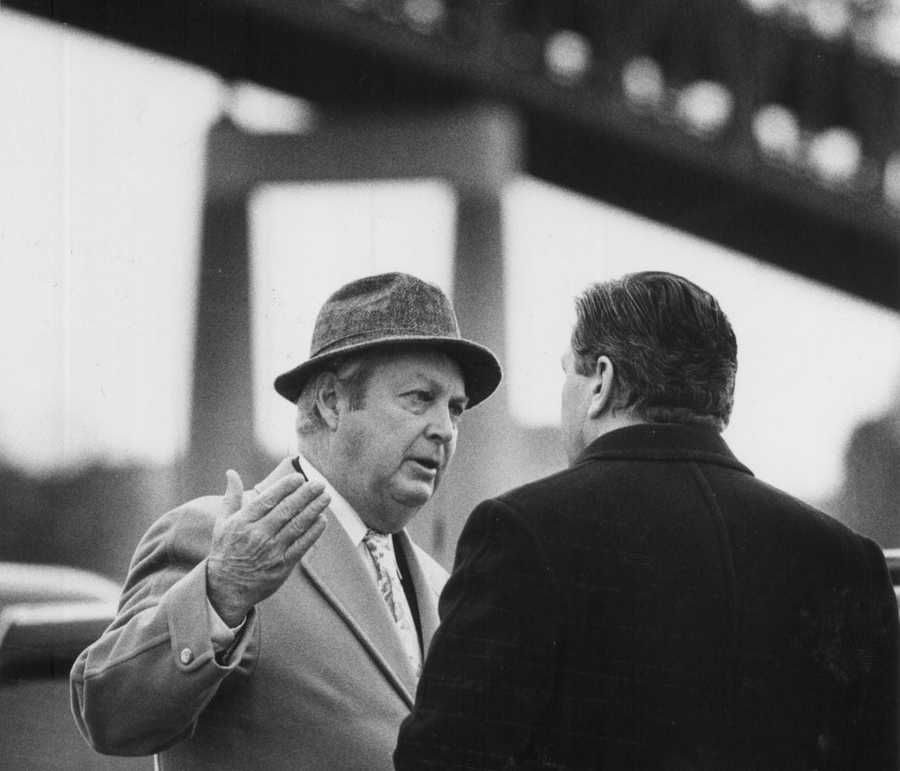

City officials scrambled. District Attorney Newman Flanagan, who had called for the return of the death penalty just months earlier, now briefed the media at the river’s edge.

The car on the bridge, he said, was Chuck’s. The note left on the passenger seat said he loved his family, the last few months had been hell, and the allegations had taken his strength. Police were searching locations in Revere for more evidence.

But this briefing — conducted before Chuck’s body was even pulled from the water — wasn’t revelatory. It was spin.

Despite the fact that the police and prosecutors had aimed all their firepower at Mission Hill and Willie Bennett, and were only now, months after the murder, searching on Chuck’s side of the river, Flanagan told a throng of reporters that Chuck had always been a viable suspect. He blamed the media for naming Willie at all and credited police with cracking the case.

“We have been very professional on this matter,” Flanagan said.

“The media has mentioned a number of people and focused in on a certain individual. Our office has never made any statement on this matter and our investigators have been constantly working on this matter and we have not ruled out anybody,” Flanagan insisted. “I think it’s fair to say that as a result of the hard work and effort, the investigation moved dramatically and focused in on Mr. Stuart.”

00:00

00:00

Privately, the police were a little more blunt. Detective Peter O’Malley, the lead investigator on the case, called police officer Billy Dunn at home and exploded. That [expletive] asshole jumped, Billy remembers him saying.

O’Malley was harried, and he got off the phone fast. But not before the detective told Billy that the higher ups were panicking.

The case had shined a light on a side of Boston that a lot of people in power felt was best left in the dark.

The city, Billy remembers O’Malley saying, they want us to stop the investigation. Right now. It’s over.

In Revere, Chuck’s family gathered in his parents’ living room and watched on television as the news cut to a shot of the divers surfacing at the stern of a police boat on the Mystic.

They had found Chuck’s body. The men on the boat reached down and hauled him up. He was wearing jeans, white sneakers, a black windbreaker. The body disappeared over the lip of the boat, and a man in a dive suit shook out a blue body bag. In the Stuarts’ living room, Chuck’s mother, Dorothy, stared straight ahead.

Not far away, Carol’s family struggled to understand the news as it played out live. They had never — not once — suspected Chuck. The DiMaitis had visited him in the hospital, had him over for dinner, cried and prayed and mourned Carol together.

The night before Chuck’s suicide, one of Chuck’s brothers had called the DiMaiti home. Carol’s brother Carl DiMaiti picked up and later recounted the call to journalists. Tomorrow’s going to be a terrible day, Chuck’s brother told him, and I just want you to know that I’m sorry. He had refused to explain, Carl said, and Carl hadn’t known what to make of it.

Now, as the meaning became clear, Carol’s father collapsed. Someone called for an ambulance.

Among Black Bostonians, the news hit much differently.

In Mission Hill, Willie Bennett’s mother, Pauline, swung the door of her apartment open and faced a pack of reporters. She shook her head.

“All the time, my son didn’t have nothing to do with it,” she said sadly and slowly. “He was innocent all the time.”

00:00

00:00

For weeks, the Bennetts had been telling anyone who would listen that Willie didn’t kill Carol or her baby. Nobody believed them. Now, one of the reporters tried to joke with her as he held up a sheet of paper to get the color balance for the camera just right. “Gotta be used to it by now,” he said, with a half-hearted chuckle. Pauline just looked down.

Willie was still in jail. Just one week earlier, Chuck had picked him out of a police lineup. “Individual number three,” Chuck had said, his knees trembling at the sight.

“I’m just glad this [expletive] is over,” Willie’s sister, Linda, told reporters cornered outside her apartment building. She waved a gloved hand in disgust. “I don’t feel like talking.”

Willie’s nephew Joey — the 15-year-old who held the smoke session where the rumor that Willie was the shooter originated — learned via a television inside lockup that his uncle had been exonerated. Joey had been jailed for beating up Erick Whitney, the teenager who first set the rumor on its course to the police.

Joey hoped the news would free his uncle from jail and free Joey himself from the label of “snitch” that now followed him wherever he went. For now, he allowed himself a little bit of relief.

Mayor Ray Flynn went that evening to Pauline’s house to apologize, but the visit turned sour the second it began. The way the Bennetts tell it, Flynn refused a seat in their kitchen, then stood awkwardly for a few minutes before leaving. The distance between them was too vast to close.

All across Black Boston, the rage and anguish and indignity of the last 10 weeks were pouring out.

White people may have been surprised, but for the city’s Black residents, this was a rerun. Some of them had even predicted this.

That includes attorney Leslie Harris, who defended the first Black suspect the police had arrested back in October, Alan Swanson. After police arrested Willie, Leslie made what now sounded like a prophetic statement about the police on the evening news.

“What they’ve done is to give the public, through the media, some type of bone to chew on,” Leslie said. “At the expense of possibly another innocent person.”

But Leslie, a veteran public defender for the poor and indigent, wasn’t a prophet. He was just a man who could see.

Since day one, he and a lot of other Black residents had been asking the same questions: Why had Chuck driven such a strange route through Mission Hill? Was he really unable to find help from a passerby at 8 p.m. on a mild night in the busy neighborhood? Why did the robber assassinate Carol with a point-blank bullet to the head and leave Chuck wounded?

“Whenever a wife is killed, the first automatic suspect is the husband,” bellowed the Rev. Don Muhammad at a news conference after Chuck’s suicide. “Except when it happens in the Black community. When it happens in the Black community, the automatic suspect is a Black man. And we’re tired.”

The mood of the city felt precariously close to the bad old days of busing. The worst parts of American history felt close at hand. Some Black leaders likened the actions of the mayor and the police and the media in Mission Hill to “night riding,” the vigilante terrorism masquerading as justice that white people once carried out against Black people across the South.

Police Commissioner Mickey Roache prepared for riots. Some people called for Mayor Flynn’s resignation.

But Flynn was certain that if he could just persuade his constituents to come together and put the whole nasty business behind them, the city would be OK.

On the night of Jan. 4, some 12 hours after Chuck jumped, Flynn went on television to defend the police and urge people to be understanding. Yes, he said, Black people had been singled out, but everyone in Boston was a victim.

“I don’t say that anybody’s at fault. I think what we ought to do is, we ought to use this as an example. Use this as an opportunity to understand how fragile the situation really is around racial incidents in any neighborhood of the city of Boston or crime in any neighborhood of the city of Boston,” Flynn said. “And let’s begin a healing process and let’s try to work together not to place blame on anybody.”

A few days later, Flynn gave his annual State of the City address and urged the city to move on.

“Now is not the time to think about the past,” he said, as if such a thing was possible. As if such a thing had ever been possible.

The Stuart case is not just a story about history and race. It’s a story about gender, too.

Through all the hysteria of late 1989, no one considered the simple fact that the leading cause of death for pregnant women in America is murder. A pregnant woman is more likely to be killed by the father of her child than she is to die from anything related to her pregnancy.

The lie that Chuck Stuart told, about the Black man who killed Carol, drew on the old American myth of the Black boogeyman, and it was a lie so deep and resonant that it swallowed up all the people involved.

In the many tellings of this story, Carol has always been emblematic of something else. Sometimes, she’s an almost holy victim, pregnant and pure. Sometimes, she’s a symbol of the lengths to which a racist society will go to defend the virtue of “white womanhood.” Erased is the good friend, the beloved daughter, the saucy waitress with no time for bad tippers.

For so long, Carol has been a supporting character in the story of her own murder.

The Globe asked Carol’s family if they wanted to speak for this project. They said no. They have spent years talking about Carol, participating in TV documentaries and TV specials, and they said they have nothing more to say.

No doubt, they fear another true crime tale, which begins — as this one does — with the dead body of an innocent woman.

But there is more to this story than has been told before. Many women die at the hands of their partners, and we rarely interrogate how, or why.

This story doesn’t end with Chuck’s jump.

And much of the story — as the world knows it — is wrong.

Advertisement