The Charles Stuart Case:

Chapter 6

An open secret festers north of Boston, within the Stuart family

Autoplay audio

Chuck Stuart stopped his car on the lower deck of the Tobin Bridge a little before 7 a.m. on the morning of Jan. 4, 1990.

He sat there for a few minutes with his parking lights on. Rush-hour traffic was just starting to pick up on the bridge, a key link to the city from the northern suburbs. Soon, it would be bumper to bumper the whole length of the long steel arc. But not yet. It was still quiet enough that he could have heard the whoosh of wind from each car that passed him.

A woman driving by applying her makeup caught a glimpse of Chuck’s reflection in her compact mirror. Not enough to make out his expression — just a flash of his pale face in the dark.

As the streaks of gray light crept into the freezing sky, Chuck stepped out of his car onto the bridge. He left a handwritten note on the front seat, and he didn’t bother to close his door.

A businessman spotted Chuck as he walked to the edge, and climbed up and over the green railing. Later, when the police would push the businessman to remember, he’d be able to summon only the barest details: the man was white, medium-build; dark jacket or vest. He described him mostly in terms of what he didn’t see. Not blond; not short; no hat.

Chuck stood there on the wrong side of the railing for a second, peering down into the Mystic River.

Nobody called the police about the man on the bridge. They saw him, but they didn’t ask themselves what on earth he was doing. They didn’t look.

Just like the police, the media, and the city hadn’t really looked for the last two and a half months.

From the first crackle of his 911 call on, nothing was what it seemed. Chuck’s story was a lie. Another man was there with him in Mission Hill — but it wasn’t Willie Bennett, the supposed “mad dog” detectives arrested to great fanfare. It wasn’t a Black man at all.

If police had questioned Chuck’s story with the same intensity they brought to the Black teenagers of Mission Hill, the fur store manager’s narrative would have fallen apart. But they didn’t. Save for the two Bobbies, police largely believed him — along with almost everybody else.

The best lies are often rooted in truth, and Chuck told a lie that sounded like the truth: A Black man did it. It was a lie that played on the primal fears of white people going back generations.

And Mission Hill was at the center of it all.

It just seemed so obvious to everybody that the shooter would be found there. “Where else were we supposed to go?” one police official would demand later, sarcastically rattling off a list of hoity-toity white locales. “To the Myopia Hunt Club? Pride’s Crossing? Beverly Farms?”

Maybe not. But what about Chuck’s hometown, the mostly white North Shore city of Revere?

That’s where this story was really unfolding the whole time. And nobody was looking.

Note: Street names and landscapes have changed slightly since 1989, so some locations on this map are approximate.

Stuart family home

This was the home of the Stuart family, including Matthew. Matthew returned here after taking the gun away from the murder scene.

On the night of the murder, as nearly every police cruiser in Boston sped toward Mission Hill in search of Chuck’s blue Cressida, they all missed the silver Toyota rolling slowly out of a side street, headed north.

The following account comes from hours of subsequent police interviews, sworn grand jury testimony, and court filings.

Behind the wheel that night was Chuck’s younger brother, 23-year-old Matthew Stuart. Carol Stuart’s pocketbook sat on the seat next to him. Inside was a silver-plated .38 revolver that was missing three bullets and smelled faintly of gunpowder.

As the first calls from police dispatch went out to officers like Billy Dunn – Drop what you’re doing! All hands on deck in Mission Hill! – Matthew coasted up the highway and pulled off in Revere, rolling to a stop in front of his family’s little red Cape Cod-style home.

He slipped into the basement, where he had a little bedroom, and shoved Carol’s pocketbook — with the gun inside — into a drawer. Then he headed back out to pick up a roast beef sandwich for the buddy whose car he was driving.

As reporters swarmed St. Alphonsus Street, where Carol’s blood was drying on the pavement, Matthew dropped the borrowed car off at the Wonderland greyhound racing track and strolled back home.

He found the kitchen full of people. His mother, his sister Shelley, and his brothers Mark and Michael. They were crying and heading for the door. It’s Chuck and Carol, they told Matthew — they’ve been shot. That was all they knew. They were going to the hospital where Chuck was being treated, but they asked Matthew to stay behind with his father, who was too sick to go out.

Matthew played it cool. He told his family he’d wait with his father. His mother and siblings rushed out and drove to Boston, where things were happening fast.

Mayor Ray Flynn was holding a press conference to announce that he was calling in every available detective to work this case. The head of the Boston NAACP was begging the police commissioner to rein in his officers. The police commissioner was shrugging and asking, What am I going to do?

Meanwhile, Matthew slipped back out the door, leaving his ailing father behind, and headed around the corner to the house of his childhood best friend, Jack McMahon.

That night, as America’s attention turned to the search for the Black man, Matthew and Jack walked down a deserted set of railroad tracks to Dizzy Bridge, which ran across the Pines River in Revere, carrying Carol’s purse in a trash bag weighed down with bricks. The two men paused at the edge of the water.

They opened the purse one final time and rummaged through the jewelry, which was tucked in a smaller drawstring bag inside.

They decided to keep the wedding ring.

Let’s hang onto that, just for sentimental reasons, Matthew said.

What had started, in Matthew’s later telling, as a quick-hit insurance scam orchestrated by Chuck — a plan to steal Carol’s pricey jewelry and make it look like a stickup in a rough part of town — had apparently evolved into a fatal shooting. And after all that, Matthew was feeling sentimental about the wedding ring.

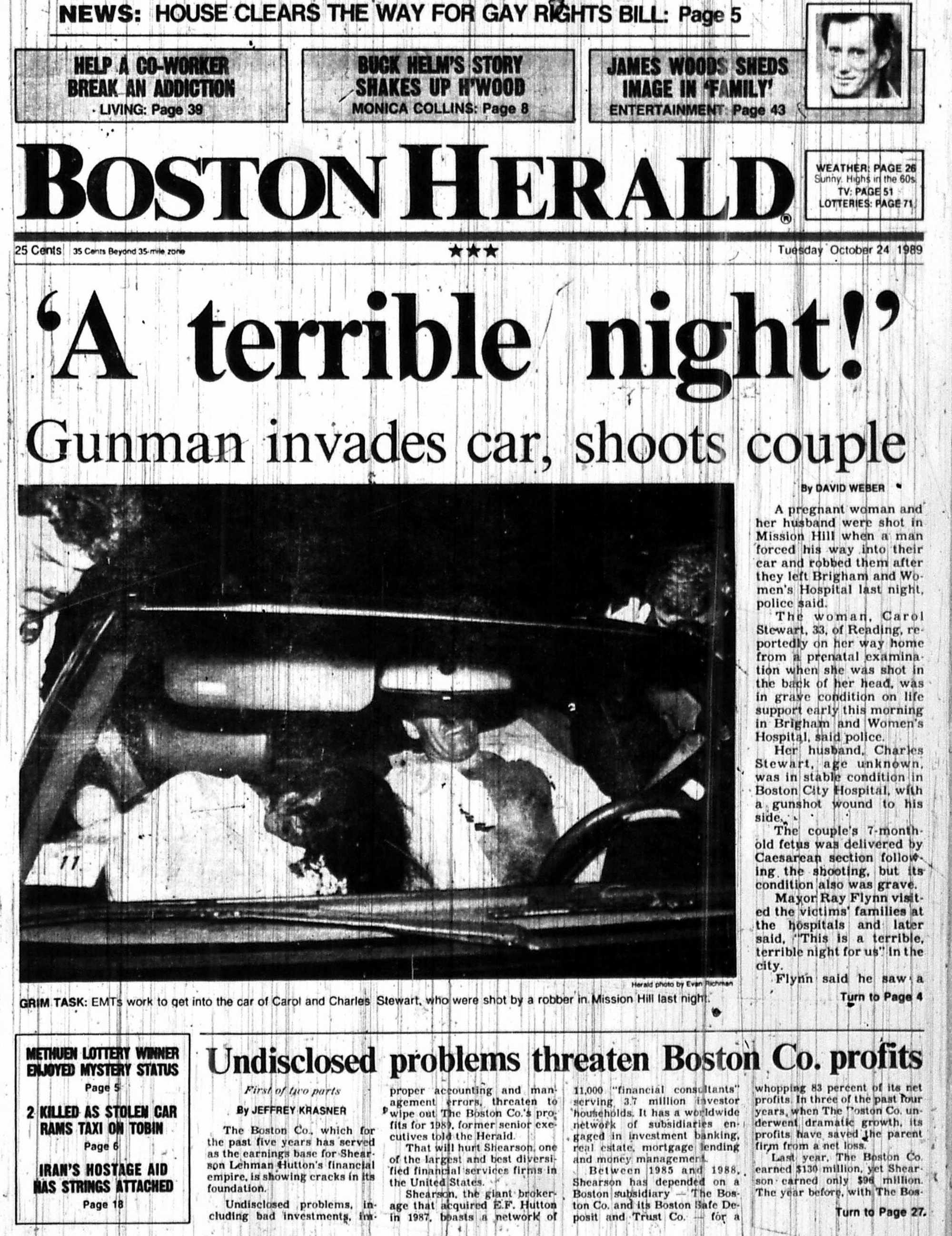

By now, Mission Hill was flooded with police. Eleven-year-old DonJuan Moses’ apartment door was flying open and the cops were pouring inside to take his cousin away. Evan Richman’s graphic crime scene photograph was being printed on the front page of the Boston Herald. Christopher Stuart was being born and Carol Stuart was dying.

Matthew and Jack put the drawstring bag with the jewelry into a trash bag with some rocks, and cut holes in the plastic so no air pocket could form and float it back up. They took the gun out of Carol’s pocketbook and replaced it with one of the bricks. They threw the trash bag, the pocketbook, and the gun separately into the water. Then they walked home to watch the news.

The next morning, Matthew Stuart called his ex-girlfriend and asked her to come pick him up.

Matthew and 23-year-old Janet Monteforte had dated for two and a half years, but they’d broken up a couple of months earlier. Matthew drank quite a bit, and he could get angry and loud. They still cared about each other, though, and Janet knew Matthew’s family. When he told her Chuck and Carol had been shot, she screamed and dropped the phone.

00:00

00:00

About a half hour later, Janet pulled up in front of the Stuart family home in her Buick. Matthew got in, and told her to drive to the Li’l Peach convenience store two blocks from his house. When she asked him why, he wouldn’t tell her. Just drive, he said, according to Janet’s recounting of the conversation to police.

At this point, Janet knew that Chuck and Carol had been shot, but nothing more. Matthew was quiet as she drove. When she pulled into the parking lot, he climbed out of her car, went inside the store, and came back out with a copy of the Boston Herald.

‘A terrible night!’ the headline screamed. Underneath was that photograph. Chuck, twisting in agony. Carol, limp and bloody. Janet looked from the paper to Matthew’s face, but he was unreadable.

We’re going to Bickford’s, Matthew said, according to Janet. I have to tell you something.

Why? Janet asked, confused. Bickford’s was a breakfast place on Route 1 in Saugus.

Just drive, Matthew said, just drive.

So Janet pulled out, and she just drove.

They had just turned onto Broadway when Matthew spoke again. He couldn’t keep the secret for one more second.

Chuck killed Carol, Matthew said. Janet stopped the car.

Matthew went on to tell this version of the story to lots of people. He told it to Janet, he told it to his brother Michael, he told it to his uncle and his friends and anybody else who would listen to him. He spread this story far and wide along the North Shore.

Is his story true? Parts of it are. Probably even most of it. But exactly what role Matthew actually played in Mission Hill on Oct. 23 — a dupe or trigger man? The Globe found that’s not so clear cut.

True or false, this is the story as Matthew told it. And this is the version that has stood as the truth for the last 34 years.

It starts a month before the murder, in September of 1989, when Chuck broke the silence of an 18-month feud with Matthew, to ask for his brother’s help.

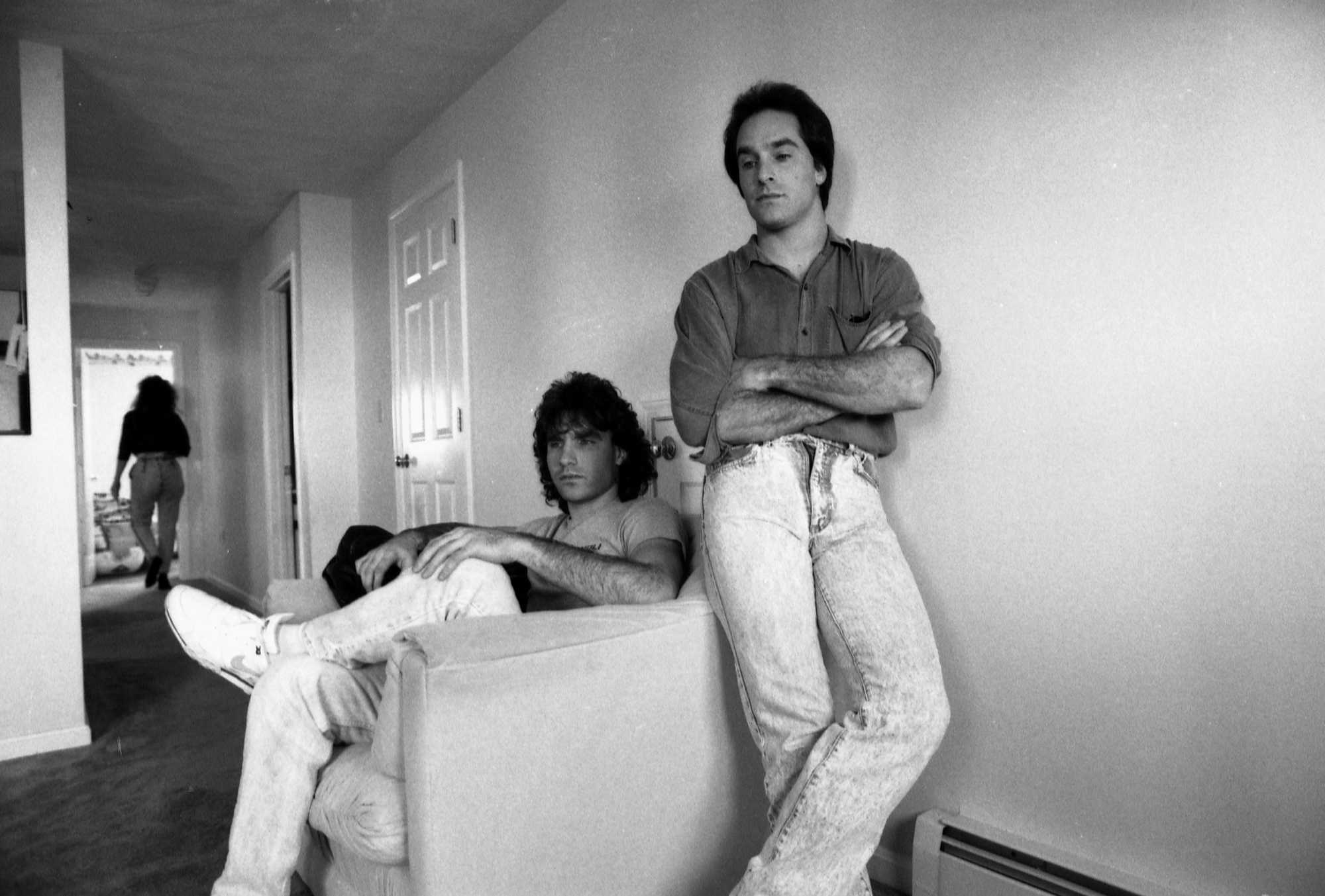

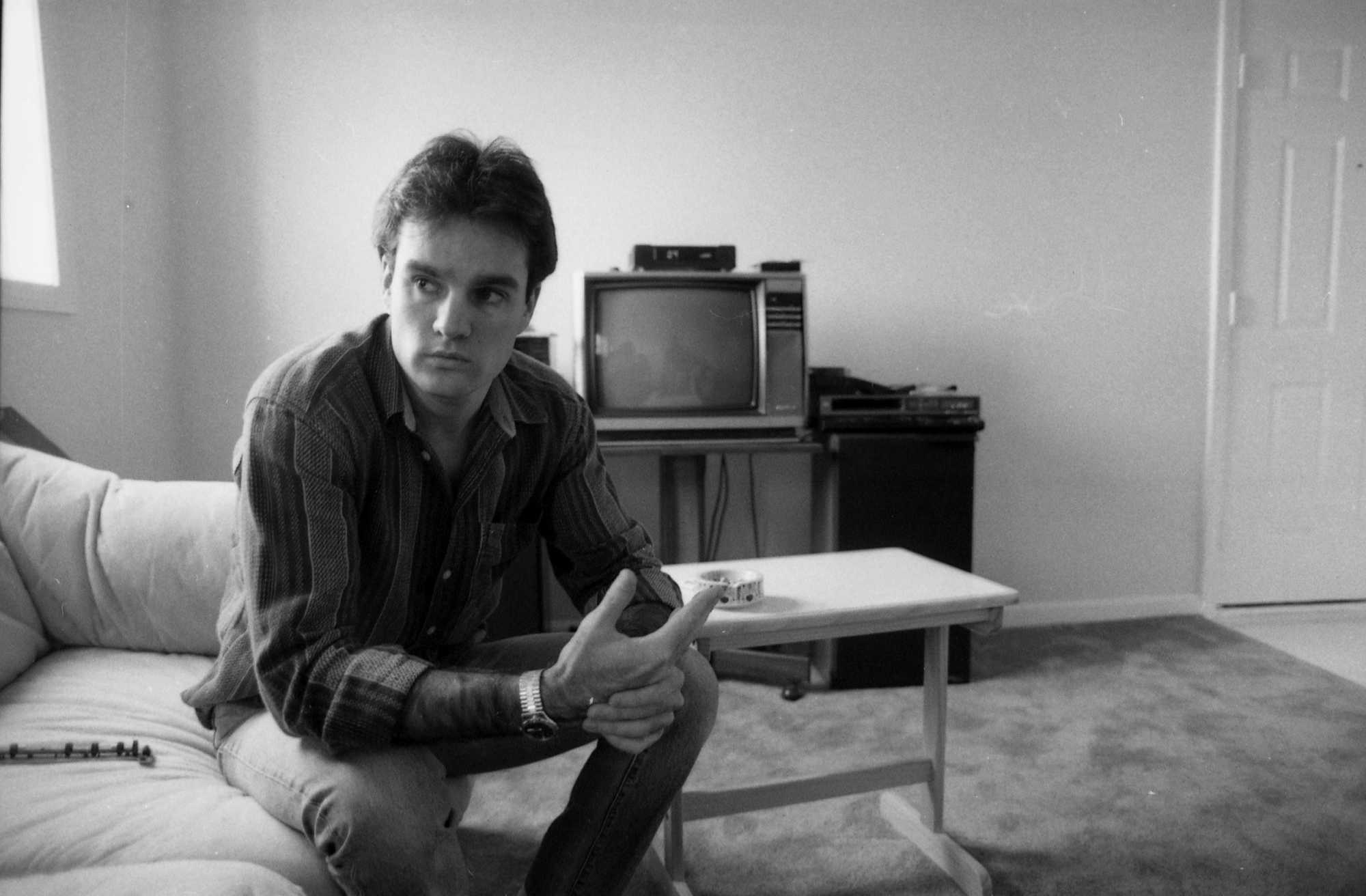

Matthew and Chuck had never been close. Chuck strutted about in a tailored suit jacket, and Matthew was the unkempt younger brother with a mullet, living in his parents’ basement, working odd jobs, and drinking until he passed out. A fight over who would do the yard work around their parents’ home had been the final straw, and they’d stopped speaking.

But by the fall of 1989, both of their parents were gravely ill. Their mother was battling breast cancer and their father, Parkinson’s. So Chuck told Matthew it was time to end their feud, for the good of the family.

That wasn’t all. Chuck told Matthew he had a plan that could make them both some money. He later testified that Chuck called it “an insurance job” — a euphemistic description for a staged robbery of his own home.

I’ll pay you for it, Chuck told Matthew, according to Matthew’s sworn testimony. I’ll make it worth your while.

But when Chuck and Matthew put their home break-in scheme into action in the middle of October, they botched it.

Matthew said he was supposed to sneak into Chuck’s empty house and take a bag of jewelry, which Chuck would report stolen to his insurance company to collect a payout. But when Matthew crept into the basement at the appointed time, he discovered that Chuck and Carol were both still home.

He wound up hiding in the basement bathroom until Chuck pretended a fuse had blown, and came downstairs to tell Matthew to run.

Matthew was rattled by the whole thing, but Chuck didn’t seem fazed. He told Matthew he had a new idea, something even easier and more lucrative — a job in town. Chuck wouldn’t tell his younger brother any details, but he said he’d pay him up to $10,000 for his cooperation.

Well, all right Chuck, Matthew said he told Chuck. It’s your operation.

On Oct. 22 — the day before the murder — Matthew said Chuck took him down to Boston. They drove past Brigham and Women’s Hospital on Francis Street, and Chuck pointed to the garage where he said he was going to park.

Chuck kept driving, over the dividing line of Huntington Avenue into the neighborhood of Mission Hill. He cruised down Tremont and hooked a left at a “checks cashed” sign, onto a little side street near a half-demolished bar where a yellow Schlitz sign still hung.

Park over here, Chuck told Matthew. Twenty past 8 or so. Then just wait for me to drive toward you and throw you a bag.

And that was it. Matthew always maintained that he didn’t ask a single question.

On Oct. 23, the night of the murder, Matthew got to the side street a little early, around 8 o’clock, he said, and bought gloves at a store nearby. There was a guy in a pickup fiddling with his truck in the spot where Matthew was supposed to park, so he waited nearby until the man drove off.

Around 8:15 p.m., he said, he saw Chuck’s blue Toyota Cressida come speeding around the corner toward him. Matthew could see something bulky in the passenger seat, but he thought it was just a pile of clothes. Matthew pulled up to Chuck’s window and Chuck tossed him the purse.

00:00

00:00

Get the [expletive] out of here, Matthew said Chuck told him. Drive slow.

Matthew said he didn’t know what Chuck had done until he saw the shooting on the news.

He would stick to this story for the rest of his short life.

That morning after the killing, Matthew and his off-and-on girlfriend, Janet, ate breakfast at Bickford’s, then went back to the Stuart family house to hang out in Matthew’s room in the basement. At some point, Jack McMahon came over and asked Janet what she thought. She told him she didn’t want either Matthew or Jack to get in trouble.

There seemed little danger of that.

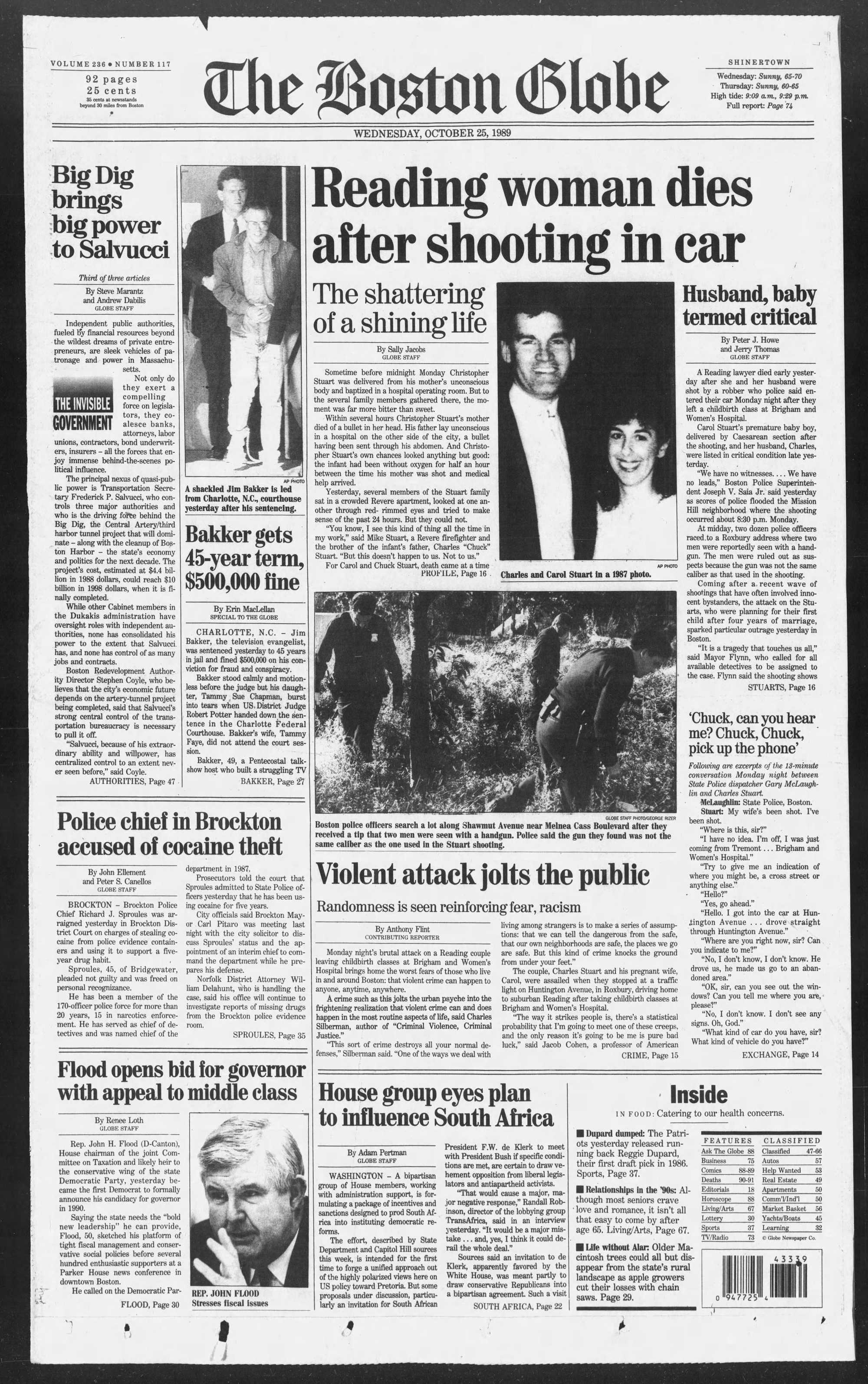

On that first full day after the murder, while Beacon Hill boomed with calls from lawmakers to reinstate the death penalty, the city of Revere was quiet, except for the media. Reporters jostled for the first interview with the devastated Stuart family.

Sometime in the afternoon, Globe reporter Sally Jacobs knocked on the front door.

Sally remembers being surprised the Stuarts let her inside. The house was filled with people crying. She walked into the living room, where the Stuart brothers were all gathered. Matthew, Michael, Mark. To Sally, they seemed shell-shocked, dazed. They didn’t seem to want to talk much, which Sally understood.

There are two things Sally remembers most vividly about that visit.

The first is the graceful turn of phrase she conjured up for her front page story the next day, to describe Chuck’s and Carol’s relationship: “so loving it warmed even those at its edge.” Today, when she says it aloud, she winces.

00:00

00:00

The second is the quiet that fell over the living room toward the end of the interview. “Over in Revere, where Chuck’s brothers and his friends gathered,” she wrote in her story, “a moment of silence hung heavy late in the afternoon.”

At the time, Sally thought the silence was grief.

The silence was more complicated than that. For some, it was grief. But for others, it was conspiracy.

Take, for example, Matthew’s and Chuck’s brother, Michael. Michael was a firefighter in Revere, two years younger than Chuck and closer to Chuck than Matthew was.

In Sally’s Globe article, Michael was quoted talking about his shock that something so terrible could happen to a family like his. “I see this kind of thing all the time in my work,” he said. “But this doesn’t happen to us. Not to us.” He said that he’d tried to warn his brother Chuck about how dangerous Mission Hill was. “I told him it’s not the best of areas. … I would never send my wife in there by herself.”

Here’s what Michael didn’t tell Sally — that almost two months earlier, at the beginning of August, Chuck had shown up at Michael’s house and asked him to go for a ride.

Sure, Michael said, he later recounted in front of a grand jury. What’s up?

They walked outside to Chuck’s van. Well, Chuck told him. I’m planning something.

Chuck talked in circles and didn’t come right out and say it. But what Chuck was implying was clear:

He wanted Michael to help him kill Carol.

Michael told Chuck no. He just said he was making about $800 a week, and he didn’t need the risk. Michael would later claim that he didn’t fully understand what Chuck was proposing.

And Michael wasn’t the only one who knew. Around the same time, Chuck had invited an old high school friend, David MacLean, out to dinner at the Ground Round restaurant in Andover and asked him if he would help kill Carol, too.

Like Michael, David told Chuck “no.” But neither of them went to the police. Not before Carol was killed, and not after.

Carol’s murder was an open secret before it even happened.

And afterward, the news that Chuck was the mastermind of the murder and the police were hunting a racist figment of his imagination traveled fast across the North Shore.

It was gossip too juicy to keep to yourself.

Matthew told Jack and Janet. Jack told his girlfriend, his mom, his dad, his dad’s girlfriend, his brother, and his brother’s girlfriend. Janet told a bunch of her friends. By the time of Carol’s funeral, at least 11 people knew that Chuck was the killer — including two of the men who carried Carol’s casket, the Globe found.

The most startling example of how casually the news spread comes from a detailed summary of phone calls — obtained by the Globe — that Janet made on a recorded line at the bank where she worked.

Janet was a clerk, and she spent a lot of time chattering on the phone to all her friends.

She didn’t discuss the moral dilemma of whether to go to the police — at least not on the recorded line, records show. Janet was wrapped up in a different matter: whether she should dump her current boyfriend, Jim, and get back together with Matthew.

I can’t turn my back on Matt, she told her friend Gina, one day after learning that Matthew had helped his brother cover up his pregnant wife’s murder. Not when he needs me like this.

The call log tracks every step of Janet’s agonizing choice.

While Alan Swanson, the first Black suspect in the murder, sat in jail, Janet fretted about whether to go on vacation to California with Jim or Matthew.

On the day that homicide detectives dragged Erick Whitney and Dereck Jackson into the precinct to grill them, Janet called Jim and told him she needed a break from their relationship, then called him back to say she was sorry.

And at the end of November, after Swanson was released and Willie Bennett arrested, Janet made up her mind.

She went on vacation to California with Matthew.

For two and a half months, the silence on the North Shore held.

A blonde woman named Debbie Allen visited Chuck in the hospital and called him almost every day. She was a 22-year-old college student who had worked with Chuck at Kakas Furs, and before the murder, Chuck had told at least one friend they were sleeping together, according to grand jury testimony. Later, Debbie would deny a romance, but while Chuck was laid up, she kept a journal for him chronicling the things he was missing: “good songs, full moons, rain storms, astrological forecasts, new jokes,” and told him she loved him, according to a letter obtained by the Globe.

When Chuck got out of the hospital, Carol’s family offered to let him live with them. Chuck demurred, saying he needed to be alone, but they made plans to have him over for dinner. Right around the new year, he moved back into the house with the pool where Carol had dreamed of raising her family. When he began to feel Debbie slipping away from him, he drafted lovelorn notes on Carol’s personalized legal stationery: “What I need right now is to hold your hand.” He bought jewelry. He bought himself a new car. He acted like he thought he was going to get away with it.

Yet, cracks were beginning to appear in the solid wall of silence his friends and family had built around him. Enough people knew now for factions to form and distrust to fester.

Toward the end of December, Janet Monteforte — who was now imagining marriage with Matthew — told her parents what was going on. And her parents did what nobody else had. They contacted an attorney and pushed for Matthew to talk.

But when Michael learned that Janet’s whole family knew the truth before he could tell his parents and other siblings, he got upset. He testified later that he had been telling Matthew all along: “Don’t just go running to the police. You’ve gotta do this the right way.” Michael was convinced that Chuck was going to try to make it look like Matthew had been the gunman. Matthew and Michael had discussed going to an attorney or wearing a wire, but the moment was never right.

Now, the moment was gone.

So, on Jan. 1, 1990, Michael called Mark Stuart, the only brother who didn’t yet know what had happened, and told him everything. Mark was aghast. After that, events moved fast.

Mark told their sister, Shelley, the next day, and the two of them together told Matthew that he had waited long enough to come forward. He had to go to the police now, or they would do it themselves. To ensure that it happened, they organized a meeting with Chuck’s own attorney and made Matthew tell him what he knew.

By the evening of Jan. 3, the Stuart siblings told their parents and another sibling, Neysa. And late that night, Matthew took a ride with the attorney whom Janet’s parents had contacted down to the Suffolk district attorney’s office in Boston. He rode the elevator up to the sixth floor, and sat down in a room with lead prosecutor Francis O’Meara, the head of the Boston Police Department’s homicide unit, and Detective Peter O’Malley.

The head of homicide, Lieutenant Detective Edward McNelley, hit “record” on a cassette player and turned to Matthew.

“Do you have a story you’d like to tell us, Matt?” he asked.

“Yes,” Matthew said.

00:00

00:00

As the sun began to rise over the Mystic River the next morning, Jan. 4, 1990, Chuck stood on the edge of the Tobin Bridge as the traffic whipped by.

It’s not clear exactly how much Chuck knew about Matthew’s confession, or whether he knew about it at all.

What is now known, through Stuart family grand jury testimony, is that Chuck had stopped by his parents’ home the day before and started grilling Matthew on whether he’d told anyone what happened. Matthew denied it, but Chuck clearly didn’t believe him. Then Chuck left to go meet with his attorney, who dropped him as a client and told him to find a criminal lawyer.

By that morning, Chuck knew enough to know it was all over. The police were closing in. He knew he didn’t have long.

But for one more second, high above the Mystic River, he was still the man no one could really see.

Advertisement