The Charles Stuart Case:

Chapter 4

Tips and rumors lead to a series of intense police interrogations

Autoplay audio

Late on the night of Nov. 3, 1989, a Boston police detective walked into an interrogation room on the second floor of the homicide unit in Southie and sat down at a table opposite a twitchy Black teenager.

The detective was Peter O’Malley. He was in his late 50s, with white hair, a paunch, and a voice as gruff and smoky as a barroom. The other detectives called him “the Colonel,” and they knew: When the Colonel walked into an interrogation room, he came out with a confession.

O’Malley was considered a closer, and the Stuart case needed closing.

And he was certain that this teenager sitting across from him was the key.

It had been 11 days since a pregnant white woman was murdered and her husband shot shortly after they left a birthing class at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

The city of Boston was gripped by an almost hysterical terror. Photographs of Chuck and Carol Stuart were everywhere — the picture of what could go wrong when a nice suburban couple ventured into what one newscast called “a city whose very arteries are coated with layers of cocaine, crack, heroin, drug dealers, drug runners, money launderers, and fast suspects in sneakers.”

The painful old wounds from the racial violence of busing were beginning to tear open, and Mayor Ray Flynn — elected on promises of racial healing — was squeezing the Police Department to make an arrest.

Worst of all, the shooter — a tall and skinny Black man with a raspy, sing-song voice — was still on the loose, despite the siege the police had laid to the public housing complex where they were sure he lived.

Inside the interrogation room, O’Malley hit “record” on a tape deck.

“Give the tape recorder your name, and talk loudly,” he said.

The Black teenager leaned forward and did what he was told: He spoke into the machine.

00:00

00:00

The rumor that would tumble out on this night would take O’Malley and the rest of the Boston Police Department weeks to untangle. Detectives would bring in one teenager after another, and each one would say something different.

To this day, 34 years later, people are still telling different versions.

But this was the story that would set Boston police on their course to finally making an arrest. There’s truth here, but there are lies and exaggerations, too, and it’s not easy to sort one from another. Not today, and not back then.

Detective O’Malley and his partner were starting at the tail end of a convoluted game of telephone.

They were trying to track it backwards. They were trying to follow it all the way to the beginning.

To the night after the murder, in a little bedroom in Mission Hill where a bunch of teenagers had gathered to smoke some pot and shoot the breeze. To the night the killer supposedly confessed.

Erick Whitney was 18, and on the short side at 5’5”, but he worked hard to look good. Every morning, he cleaned his sneakers with a toothbrush and washed his face with Ivory soap. He was a bagger at Stop & Shop, but at night he rode around in fancy cars he and his buddies boosted, trying to impress girls.

And it worked. Angela Brittle was crazy about him and had been from the moment Erick first smiled as he bagged the groceries she rang up.

He called her “Annie girl.” She was a year younger than Erick, a hot ticket in high-top Adidas, tight jeans, Care Free Curl ponytail with a lollipop sticking out. Angela was tough — she was from Dorchester, and she could fight — but Erick treated her like she was delicate, and she liked that. Nobody treated her that way.

Underneath Erick’s layers of swagger, Angela discovered a kindred sweetness. He acted like a player, but it turned out he had never had a real girlfriend. And for all his bluster about what a tough guy he was, Angela said, she sensed a vulnerability. It was in the way he talked about his mom.

Other than Angela herself, Erick’s mom was his closest confidante. She had a reputation as being “down” — which meant she was hip enough to confide real problems in. But she could be cruel and dismissive. Erick was afraid of her, and always trying to please her, and failing.

He was a teenage gangster wannabe who couldn’t make his mom love him. And it was because of this that police first heard the rumor about the Stuart murder.

Because Erick heard the rumor from his friend, who heard it from somebody else. And, Erick, eager to impress, embellished it a little bit around the edges to make himself look important and told exactly one person:

His mother.

Erick’s mother rang up a Boston cop she knew, who passed the news along to homicide. Homicide told a Roxbury sergeant who happened to be Angela Brittle’s uncle, and Angela’s uncle went and talked to Angela. And Angela, a tough girl with a good heart, did what she thought was the right thing: She persuaded Erick to come down to the homicide unit with her and her uncle to talk.

Erick and Angela walked together into the interrogation room on Nov. 3 and right away, they saw arrest warrants taped to the wall. The police knew Erick — not because he was some big-time criminal, but because he was just plain unlucky. He got pinched for every little thing. He was currently wanted for shoplifting a watch from Jordan Marsh and for breaking a car window — though he claimed he was innocent, and just happened to be holding a rock.

Word of O’Malley’s witness had gotten around the homicide unit, and a growing crowd of officers hung outside, eager to hear the Colonel break the case. And, after hours of commanding and cajoling, it looked like he had done it.

“I want you to tell me,” O’Malley said to Erick, once he finally turned on the tape recorder. “Your words.”

But Erick didn’t have any of his own words to say. He said he only had a story he’d heard from his friend nicknamed “D.”

It went like this: On Oct. 24 — the night after Carol Stuart was murdered — D went over to another friend’s house, a 15-year-old kid everybody called Toot.

D and Toot and a couple other people — Erick was a little fuzzy on who — were smoking weed and drinking 40s and playing Super Mario Brothers, when Toot started running his mouth, talking about how his uncle did the murder.

Toot said his uncle was in the car, Erick said on the tape, mumbling like he had a mouth full of marbles, trying to explain what D said Toot said his uncle said. “Told ‘em, ‘Don’t look in the rearview mirror. Give me your money and your wallet.’ So he seen the watch, then he took that.

“He got out. He saw the Stuart man reach for whatever, he thought he was 5-0 and he bust both of ‘em.”

Angela had sat in the interrogation room with Erick for a long time before the detectives asked her to leave so they could record Erick’s formal statement. She remembers eight or nine officers, almost all of them white, crammed into this dark little room with too few chairs. The homicide unit wasn’t far from the airport, and every time a plane flew overhead, it rumbled so loudly that they all had to stop talking until it passed. Later, the police would deny it, but Angela remembers they were cursing at Erick, and saying he’d be arrested if he didn’t tell them what he knew.

Toward the end, Angela sat across the table from Erick. He faced the door; she had her back to it. Behind her, she heard the door open and she watched Erick’s face go slack with fear.

She watched his eyes widen at the man who stood behind her.

Do you know who the [expletive] I am? came a deep voice. She watched Erick nod — yes.

Who am I? the voice demanded.

Angela turned to see a hulking white cop as big as a refrigerator filling the doorway. Erick’s voice was small when he finally answered.

Billy Dunn, Erick said.

O’Malley had called in “the Legend.”

Billy Dunn knew Erick. He knew D and Toot and all the other kids in Mission Hill, too. He used to joke that their mothers told him their names before they were even born.

O’Malley knew he couldn’t navigate the mazes of Mission Hill without a guide. He could barely even understand the slang. O’Malley thought of Billy as his interpreter and his lie detector: Billy’s very presence could scare anybody into telling the truth.

So when O’Malley heard the first few beats of Erick’s story, he called in Billy, and he asked him to go get Erick’s friend D.

Several hours later, D — a 17-year-old high school student named Dereck Jackson — sat in front of O’Malley and offered another version of the rumor.

And in Dereck’s telling, it was Toot’s uncle himself who told Dereck he did the murder.

But Dereck’s story, Erick’s story, the answer that O’Malley was so sure he could find at the end of the game of telephone? It’s all a lie, at least according to the guy who supposedly kicked this whole rumor off.

“You can’t make this [expletive] up,” said a man named Joey Bennett, three decades since O’Malley first hit “record.” “Oh but they did make it up.”

Long ago, Joey just went by Toot. He was the crack-dealing, car-stealing, protector-of-his-family, the 15-year-old kid who held the smoke session that launched the rumor.

00:00

00:00

Joey’s family, the Bennetts, was one of the most well-known families in Mission Hill, having arrived in the late 1960s. Joey grew up playing marbles, having block parties, and opening up the fire hydrants to shoot geysers of water into the streets in the summer.

When crack tore through Boston in the ‘80s, though, it wrecked practically Joey’s whole family. His dad wasn’t around, so Joey took care of his little brother. At 12, he started selling crack himself. Eventually, he said, social services took him and his brother away from their mom and moved him into his grandmother’s apartment on Alton Court, hoping to turn him around.

But as much as his grandmother loved him — which was maybe the most anybody ever loved him — it wasn’t enough to reform Joey. By 13, he was carrying guns. By 14, he’d been shot. By 15, he was running with grown men and driving stolen cars.

So back to the smoke session. Back to Joey’s room. Back to the birth of the rumor.

The night after the murder, Joey recalled, he laid low. He had never seen so many police officers in Mission Hill. All he wanted to do was get back to the stolen car and gun he’d ditched a few blocks away the night before. But in the wake of Chuck’s 911 call, he knew that would be a stupid move. The cops were stopping everybody.

Instead, Joey decided to have Dereck and a couple other buddies over to smoke weed in his room.

So there they were, smoking and drinking, a giant boombox speaker on a dresser, and the Nintendo on the floor.

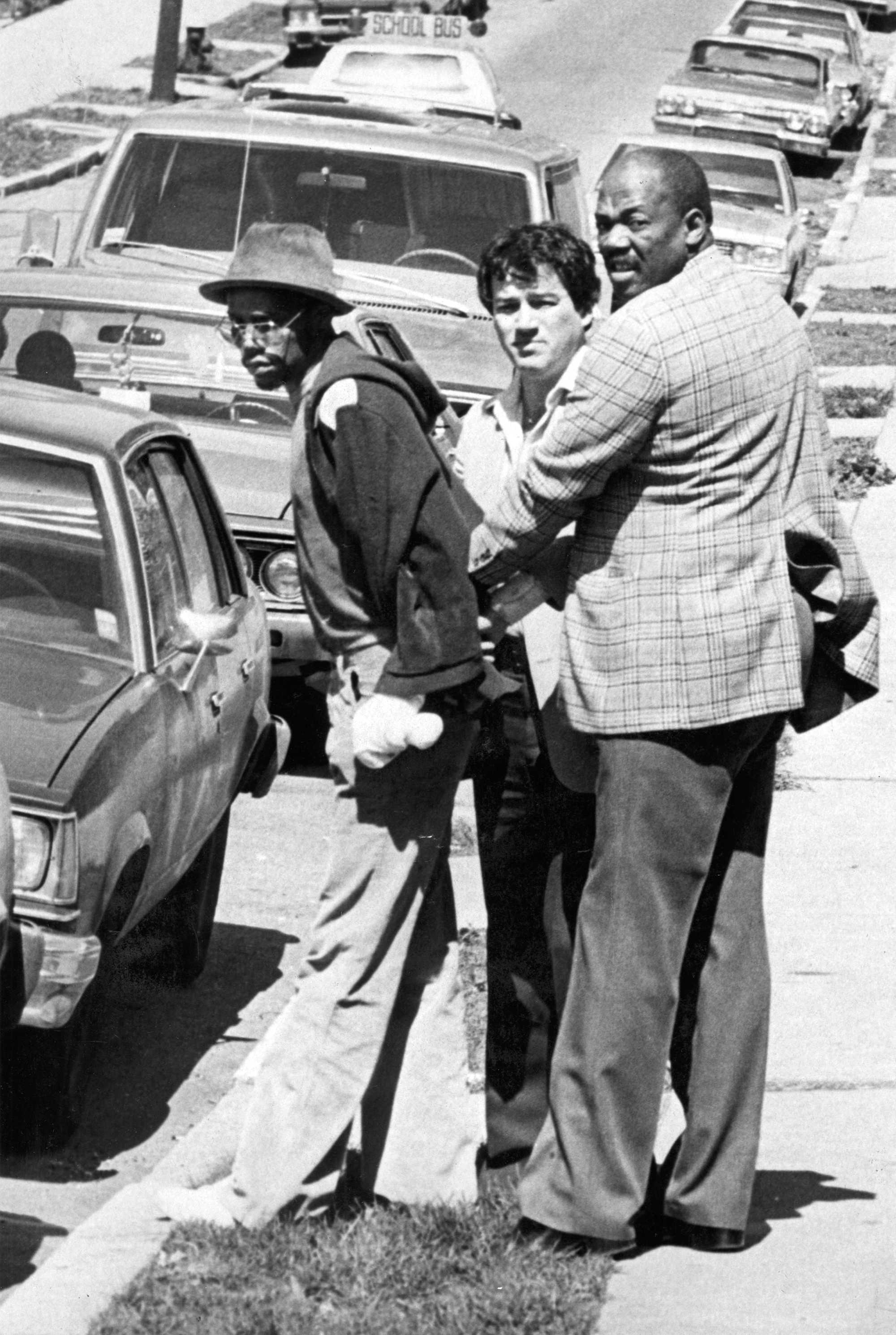

And that’s when one of Joey’s friends noticed a framed newspaper article sitting on a shelf in Joey’s closet. It was a faded clip from 1981, front page of The Boston Globe metro section, with a big above-the-fold photograph of a skinny black man in handcuffs surrounded by police officers. The headline threatened: “You’re not going to take me alive.”

Yo, who’s that? Joey remembers one of his friends asking.

Joey smiled.

That’s my uncle, he said.

Joey’s uncle. Wild Bill. Willie Bennett.

“Every police officer’s nightmare,” Joey’s framed article began, and that wasn’t even the half of it.

In a time when “F**k tha Police” seemed to blast out of every stereo system, Willie Bennett was a living embodiment of the lyrics. He was a one-man army.

Once, when a cop tried to pull him over for driving with an expired license plate, Willie pulled out a sawed-off shotgun and held the officer up right from the driver’s seat of his car. Took the cop’s gun, shot out the front left tire of his cruiser, and drove off. Another time, Willie and a friend opened fire on a pair of officers who had been chasing them over a stolen car.

Just about everybody in Mission Hill knew Willie. Kids looked up to him, and grown men stayed out of his way. Willie wore linen suits, suede jackets, and fancy shoes. He had girlfriends in different cities.

Joey at 15 was a hard kid, but he was still just a kid. And he idolized his uncle. Willie was his hero, and Joey wanted to be him.

The framed article in Joey’s closet was about the final showdown Willie had with police before the Stuart shooting. “You’re not going to take me alive,” he had shouted at officers, crouched in the apartment where they found him aiming a .357 magnum revolver. But — improbably — they did, shooting Willie once in the hand.

Joey remembers saying that night during the smoke session with his friends: “That’s my uncle.”

In Joey’s telling, this was the full extent of the exchange with his friends in that smoke session. He said he never linked Willie Bennett to the Stuart shooting.

Joey says he was just a kid proud of his neighborhood-famous outlaw uncle.

Boston police — especially Billy Dunn — knew Willie, too. He heard about it when Willie got out of prison toward the end of the ‘80s, when he finished his time for the crimes written up in Joey’s article.

Billy remembers the moment they met.

It was late, Billy recalled, and he was driving around Mission Hill with his partner. They saw a guy standing in a dark doorway, and they didn’t recognize him. They pulled up.

What’s your name? Billy said, recalling the exchange.

You know my name, the man said from the shadow.

What’s your name? Billy asked again.

Willie, the man said.

Willie Bennett.

00:00

00:00

Geez, Billy said, I heard a lot about you.

The reply, as Billy remembers it, came low and deadly: I heard a lot about you. And if you get in my way, I’ll kill you.

Billy recalls he didn’t break eye contact. I think I’ll kill you first, he said. Get out of here.

So when the police heard that Willie Bennett was walking around Mission Hill bragging about shooting the Stuarts, they weren’t surprised.

Erick and Dereck weren’t the first people to tell police they should look at Willie for the shooting — his name had come up just a few days into the investigation, in the form of an anonymous tip: “Word on the street is, Bennett did it.” There had been reports of Willie running through the public housing complex with a gun that night and raging afterwards that he never meant to shoot the woman.

But those stories were vague and confusing. What Erick and Dereck said in the interrogation room sounded solid.

Or so it seemed, when O’Malley finally hit “stop” on his tape deck.

But one day later, Erick and Dereck returned to the homicide unit in Southie. They were there to take it all back.

O’Malley only recorded one interview on Nov. 4, the day the teens tried to recant. The tape is old and scratchy, but the anger in his voice is unmistakable.

“Why were you lyin’ to me in a murder investigation? Tell the machine that.”

Erick mumbles and is almost incoherent.

“I made — I made that story up,” he said. “My my my my my girl said you was gonna put my… twenty years in Walpole, I flipped out, I was scared, I came, I said anything …”

Walpole was a prison. Erick was trying to explain that he lied and told O’Malley what he thought he wanted to hear so that O’Malley wouldn’t send him there.

Erick’s hands were wet with sweat. O’Malley noticed.

00:00

00:00

“Does that mean you’re nervous?” the detective growled.

“It means I’m scared,” Erick said.

“You’re scared?” O’Malley asked. “Do I look like I’m going to beat you up?”

Erick said no. He was afraid of going to jail.

In the end, it didn’t matter that Erick tried to recant. O’Malley didn’t believe him. O’Malley didn’t bother to record an interview with Dereck. The teenagers left the station, and a little less than two weeks later, they testified to their original stories before the grand jury. A week after that, they went back before the grand jury and recanted again.

But the version of the rumor that Erick and Dereck had told on that first night was the only one that counted. It had given the detectives everything they needed to solve the case.

Erick Whitney is dead now. He was stabbed to death in 1999. There is no way to know what he would say about all this.

Dereck is alive. He still maintains that Joey did say that his Uncle Willie did the murder. But his story about Willie confessing, he says, was a lie.

Dereck was a black teenager surrounded by white cops in the homicide unit in Southie. Southie was not a place Black people went.

“A scared kid,” Dereck said. “We said — I said, what they wanted me to say.”

Angela — Erick’s girlfriend, who persuaded him to come to the station in the first place — remembers a deep sense of foreboding about what forces they had set in motion.

“What’s going to happen now?” she remembers wondering, after Erick’s interview in homicide. “This is a pregnant woman. This is a white woman. This is not going to roll over easy.”

The police used Erick’s and Dereck’s testimony to raid three homes connected to Willie: two in Mission Hill, where his mother and girlfriend lived, and one in Burlington, where he was staying with another girlfriend.

Billy Dunn was one of the first officers through the door at Willie’s mother’s home. There, they found a .38 bullet in the wall — the same caliber as the one the medical examiner recovered from Carol Stuart’s head.

They arrested Joey on cocaine charges, though the officer that found the little white bag of powder was notorious for dishonesty and the powder later tested negative for drugs. It didn’t help the police case anyway — if detectives thought Joey Bennett was going to give an interview ratting on Willie, they were disappointed.

Willie wasn’t in Mission Hill the night of the search warrants. Officers arrested him in Burlington on an outstanding traffic infraction. They couldn’t charge him with the murder — not yet. So they kept him in jail on unrelated charges while O’Malley and his partner worked to build their case.

Willie’s photograph made it into the papers again. And this time, the police were sure they had the killer.

Detectives just needed Chuck to make a positive identification.

Seven weeks later, on Dec. 28, they would get it.

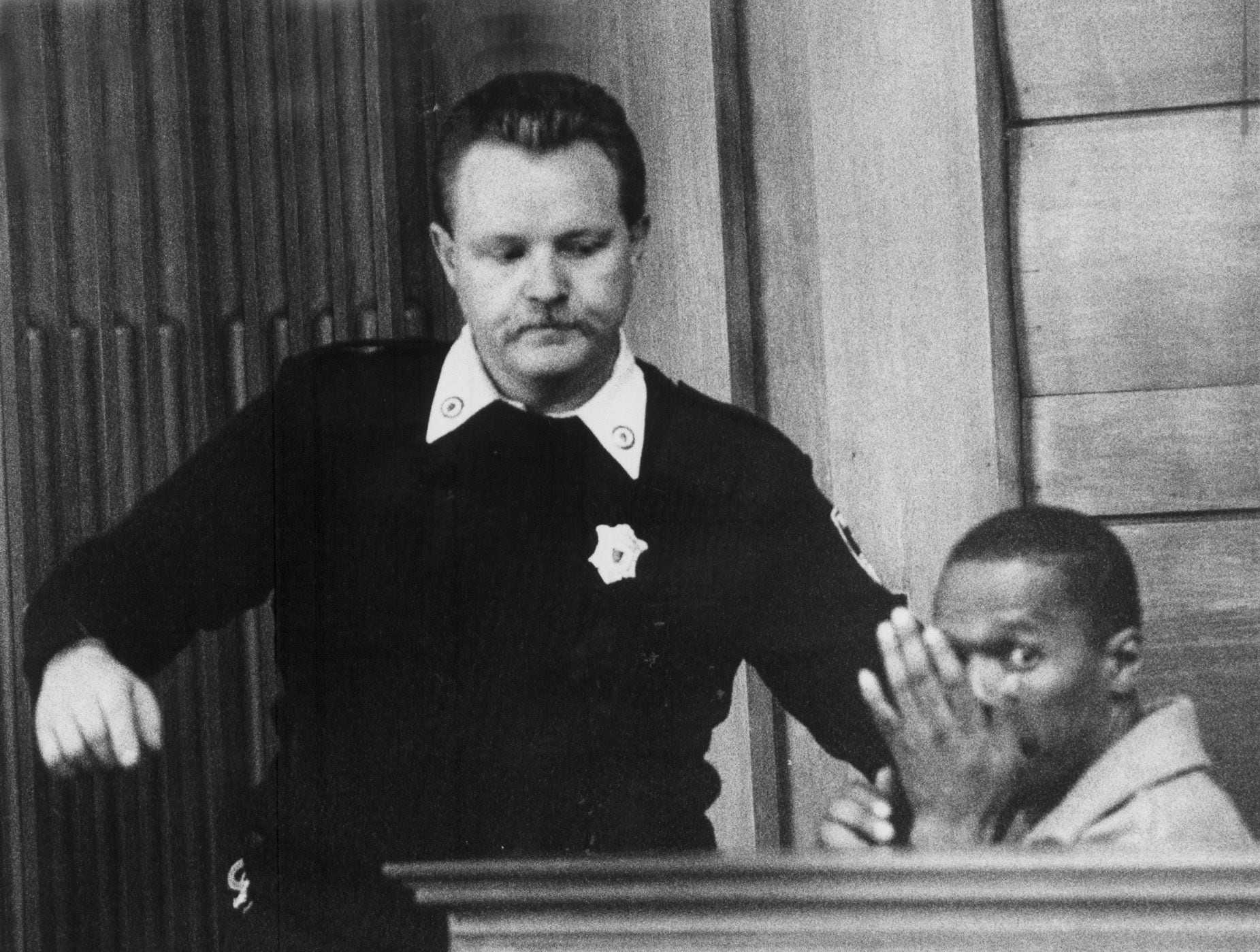

Chuck Stuart was finally strong enough to come to police headquarters and look in through the one-way glass to a little room where eight Black men were lined up, holding cards with numbers on them.

One at a time, the officers asked the men to step forward. When Chuck saw number 3, his legs started shaking.

It was the skinny Black man who murdered his wife and child.

Chuck pointed to Willie.

Advertisement