The Charles Stuart Case:

Chapter 2

The pressure builds and a police manhunt envelops Mission Hill

Autoplay audio

Homicide Detective Robert Ahearn chugged bitter coffee out of a paper cup and squinted down at the police reports spread across his desk. Something about this case was bothering him.

It was Tuesday, Oct. 24, 1989, the morning after a seven-months pregnant woman and her husband were shot leaving a birthing class at a renowned Boston hospital. Now, Carol Stuart was dead. Doctors had managed to save Chuck, who was shot in the gut. Their baby, Christopher, had been born by caesarean section and was barely hanging on.

Ahearn and his partner, Robert Tinlin — “the two Bobbies” — had been up almost all night. First, at the crime scene in Mission Hill, where paramedics found Chuck and Carol Stuart in their blue Toyota Cressida. Then, at the district police station where the mayor went on TV to announce he was ordering every available detective in the department to work the case.

That, right there, was part of what was bothering Ahearn: the publicity, the pressure. He could practically feel the mayor’s hot breath on the back of his neck.

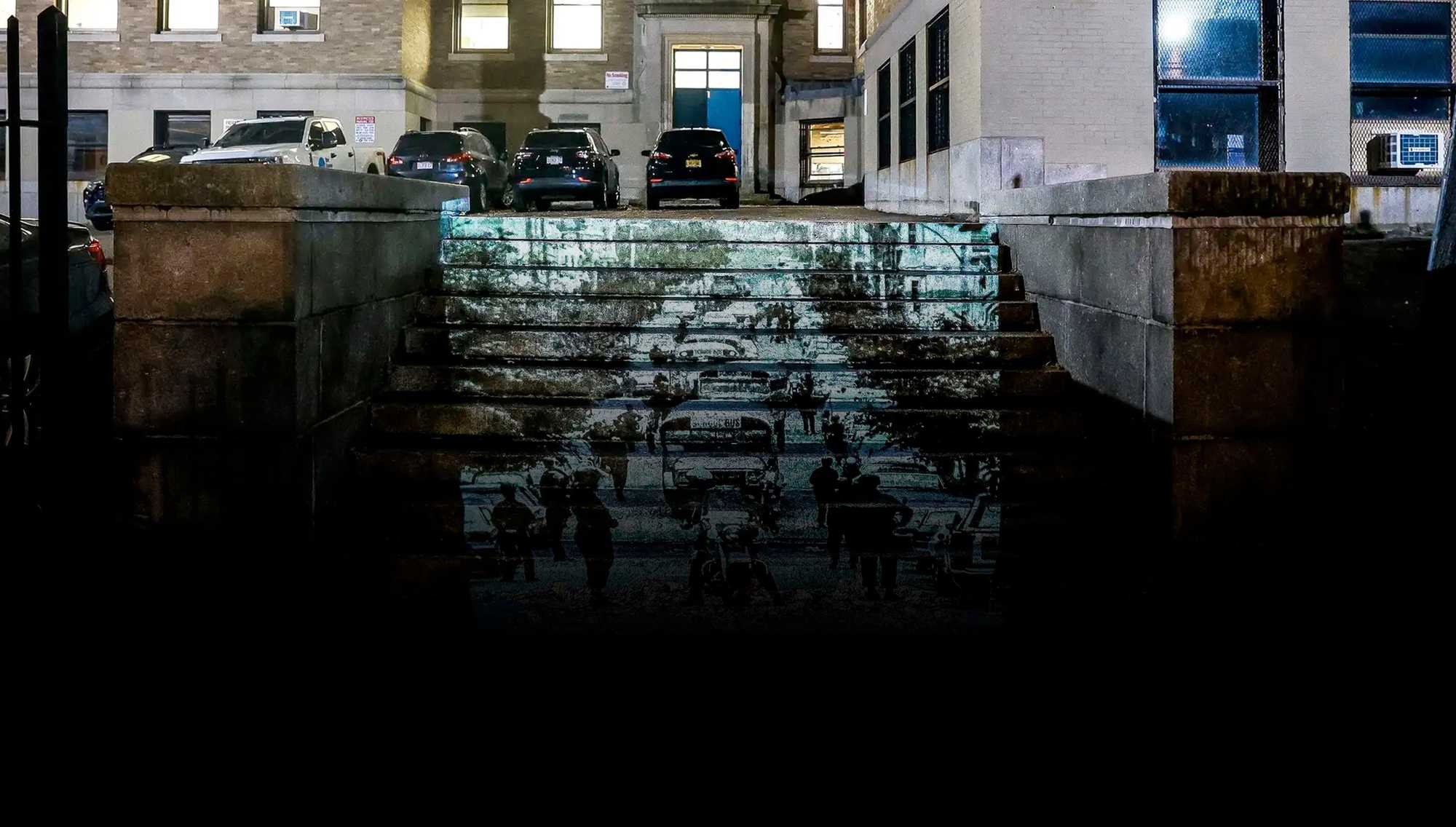

Boston police officers searched a lot near Melnea Cass Boulevard on Oct. 24, 1989, looking for the gun used to shoot the Stuarts. A Boston police officer detained a Black male in a Mission Hill public housing complex on Oct. 25, 1989. (George Rizer, Tom Landers /Globe Staff)

This wasn’t just a homicide investigation, this was a task force. There was a hot line. Hundreds of cops and dozens of reporters were crawling all over Mission Hill, undoubtedly tromping on evidence and hassling witnesses.

Chuck had only managed to give the barest description of the shooter before he was rushed into surgery — Black man, late 20s or early 30s, wearing a black track suit with red stripes. Those few, simple details cascaded across the news, reaching as far away as France. And now, the phones in the Boston homicide department were ringing off the hook with reports of suspicious Black men in liquor stores, in gardens, looking in car windows, and running down the middle of the street.

It was a goddamn headache.

Ahearn finished his coffee and tucked the paperwork back into the case jacket. What he wanted most was to talk to Chuck, but that wasn’t happening today. Chuck was heavily medicated in the ICU.

And that was the other thing. Chuck himself. Ahearn and Tinlin both felt it — there was something off about that guy.

When Chuck had called 911 to report the shooting, a reality television film crew just happened to be riding around with the responding EMTs. The cameraman had followed Chuck all the way into the operating room, where he filmed Chuck naked and asking for his wife. Ahearn and Tinlin had watched the raw footage the night before. The news was going crazy over Chuck’s bravery, but to the detectives, he seemed too calm.

Unfortunately, the interview with Chuck would have to wait.

Ahearn stood up and walked out of his second-floor office and down to the garage. The Stuarts’ Cressida still needed to be swept for prints and hairs and trace evidence. And then he needed to understand the exact route that Chuck had driven from the hospital, what happened between the time when he and Carol got shot and when they were found in the Mission Hill public housing complex.

There must be witnesses, people walking or driving or just looking out their apartment windows. Maybe the patrol officers had already started rounding them up.

DonJuan Moses woke up late that morning to the sound of adults talking angrily in the living room of his family’s Mission Hill apartment. He was 11 years old, and he knew something bad was happening. But he didn’t know what it was.

All he knew was that he was afraid. The night before kept replaying in his head.

They had all been in the kitchen. His mom, grandma, and older cousin were hosting a raucous game of spades at the table, and DonJuan stood over his grandma’s shoulder, watching the cards fly from her soft, sure hands. He remembered the music was bumping, everybody was laughing, and he felt his heart beat with the adrenaline rush of being a little kid up late with the grownups. His grandma said he could be her partner, and he took it seriously, screwing up his face in concentration to “count the books” like she’d taught him.

It was then that he’d noticed the blue lights out the window. He’d walked over to peer outside, curious. Mind your business, his mom said over her shoulder, and he’d walked back to the table. But it wasn’t long before DonJuan started to hear the low thunder of heavy footsteps — men, stampeding, somewhere inside their apartment building. Getting closer, coming up the stairs.

00:00

00:00

Playing cards slid across the table. The footsteps arrived outside their door. From the hallway, someone started pounding on it, and DonJuan felt the pounding in his chest. All these years later, he can still feel it. His mother looked up, but before she could say anything, DonJuan walked over and turned the handle.

He remembers the next few seconds stretched out long and loud and slow. The door burst open and police poured in. They were yelling about a shooting, and a description that matched his cousin. DonJuan’s mother was yelling back. One of the officers was grabbing his cousin, standing him up and slamming him forward on the table.

DonJuan backed up out of the kitchen, until he hit the piano that some long-gone tenant had somehow dragged up three flights of stairs. “Whoever heard of a piano in the projects?” his mom had always said. In this moment, nothing made sense to the 11-year-old boy. DonJuan couldn’t breathe.

The cops cuffed his cousin and yanked him out the door and down the stairs. The kitchen emptied out. The footsteps receded. It was like a wave had crashed in and swept his cousin away.

DonJuan remembers spending the rest of the night in his bedroom, standing sentry at the window, watching in case the police came back. He had finally fallen asleep just before dawn, until the adult voices woke him up.

Now, he recognized his cousin’s voice, and he jumped up and ran into the living room.

This is bullshit! his cousin was yelling. DonJuan froze at the edge of the room, and the adults ignored him. They had just gotten home from bailing out his cousin, and they were talking over each other about money and lawyers. None of it meant anything to DonJuan, who didn’t even know about the murder yet.

DonJuan was relieved that his cousin was safe, but he didn’t understand what his family had to do with what was going on. Outside, police in uniforms and plainclothes walked through the tall grass in the alleyways, studied tire marks in the road, and jogged along the rooftops.

His mother’s words from the night before rang in his head.

These piece of [expletive] police, she’d fumed. They back at it again.

Louis Elisa had almost no advice to offer.

Every time his phone rang with another panicked call about what the police were doing in Mission Hill, the president of the Boston chapter of the NAACP repeated this message:

Stay inside, and lock your door.

But deep down, he knew it wouldn’t help. If the cops were coming, the cops were coming.

In theory, the police were searching for the suspect Chuck Stuart had described. In practice, they were stopping almost every young Black man they saw, making them empty their pockets and identify themselves. Not even just Black men — Hispanic men, too. Teams of officers were conducting sweeps, picking up teenagers and young men on outstanding arrest warrants and squeezing them for information. Louis was getting calls about police dragging people out of their homes.

People like DonJuan’s cousin — who was released without charges after less than 24 hours.

For months now, the Boston police had “stopped and frisked” young Black males they suspected of gang activity — a flexible and expansive concept that often ensnared kids just hanging out.

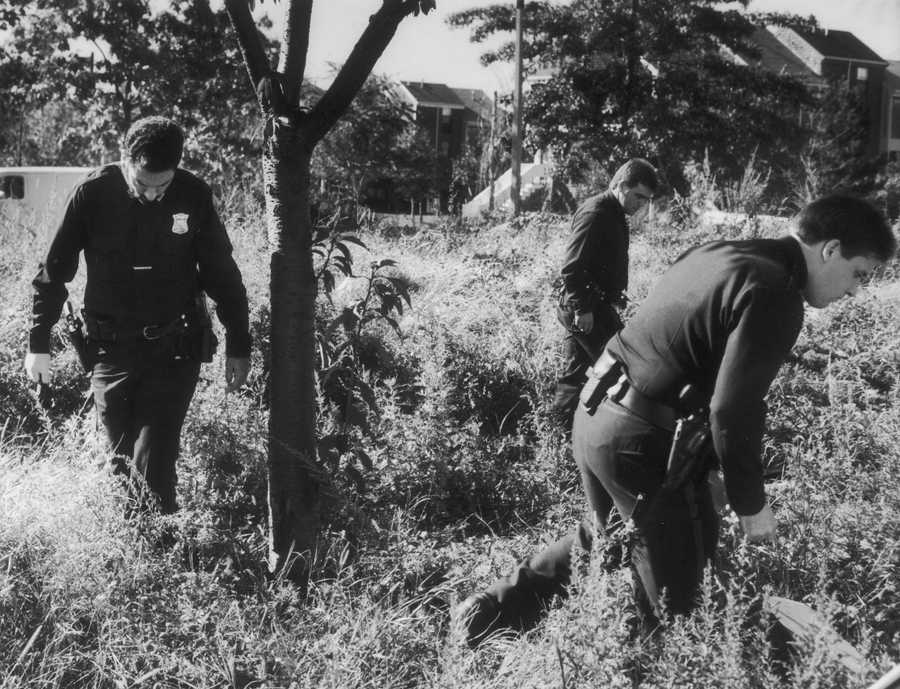

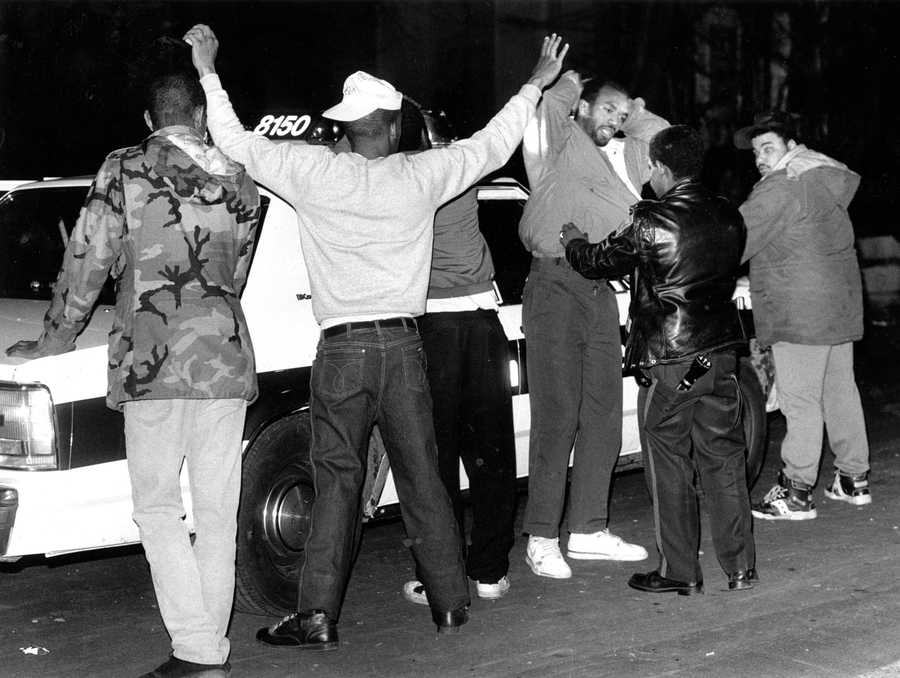

A Boston police officer searched a man in the Academy Homes public housing complex in 1989 after residents reported hearing gunshots. A Boston police officer searched a group of men in Roxbury in March 1989 while investigating a report of gunfire. (John Tlumacki/Globe Staff)

A lot of people thought this was the only way to keep the city safe. They called the summer of ‘89 Boston’s “hot summer,” because the number of killings and shootings were in the midst of a bloody spike, on their way to doubling in just three years. And the cooler fall weather didn’t slow the violence. Since September, more than 100 people had been shot or killed, and the police were talking about a “reign of violence.” Stop and frisk had become a court battle. A Superior Court judge had ordered the Boston Police Department to stop — and the department had flat-out refused. What were they supposed to do? cops asked. Just show up after the victims were dead and ask politely what happened?

But now, after last night’s shooting, Louis was starting to hear about cops forcing young Black boys and men to strip off their clothes in the street. To Louis, it was starting to seem more like a police riot than an investigation.

Louis had already appealed to the mayor directly, asking him to temper the police response.

Louis had been at a ceremony of Free Masons when the shooting happened, and when he heard the details — white couple, pregnant woman, Black shooter, Mission Hill — he headed straight to the Roxbury district police station, still wearing his tuxedo. When he arrived, he saw the cops assembling with riot shields.

Mayor Raymond Flynn and Police Commissioner Mickey Roache were about to hold the press conference in which Flynn would promise a citywide response with tactics as aggressive as the law would allow.

Louis had made his way over to Flynn before the cameras started rolling: Stop, he said. Think. Why would a robber carjack a couple in a busy neighborhood, murder the woman, and leave the man alive? This isn’t New York City, he told the mayor — a reference to the Central Park Jogger case from a few months earlier, in which “wilding” Black teenagers were accused of brutally raping a white woman. The publicity around that explosive accusation — which later was disproved — had led to widespread panic and calls for the return of capital punishment in New York.

But Flynn had just looked at Louis and said, You don’t know what you’re talking about, Louis recalled.

So Louis had turned to Roache. Mickey, you’re the commissioner, he said, but Mickey, Louis said, shook his head. What am I gonna do, Lou? You know, I mean, he’s the mayor.

Louis still burned with anger and frustration. But he didn’t have time to stew. He needed to find a different way.

00:00

00:00

So, on Tuesday night, about 24 hours after the killing, he agreed to an appearance on a nightly TV news show, hoping to reach the powers that be through the television screen.

“Shock, outrage, fear,” the anchor intoned, as the program started, before interviews with police officials and the mayor.

But Louis’s message — that police and politicians were reacting with too much force — was drowned out by a message from the Suffolk District Attorney Newman Flanagan, the prosecutor overseeing the case.

All day long, politicians, lawmakers, and regular citizens had been calling for the reinstatement of the death penalty for the murderer of Carol Stuart. And seconds after Louis urged caution in the city’s response, the camera cut to Flanagan, who looked like he might have been awake all night.

Flanagan pointed straight out at the viewers and challenged them to listen to Chuck Stuart’s 911 tape. Imagine him, he said, watching his wife die.

Then, Flanagan made his final point. In a case like this one, he said, capital punishment should be on the table. The killer should get the death penalty.

By the day of Carol’s funeral, it seemed practically every person in America had seen her wedding photos. The TV news had beamed them all over the country — Carol, with her dark curly hair and huge grin; Chuck, smiling almost shyly into the camera’s flash. The Boston Herald had started calling them the Camelot Couple, and the national media had picked up the tabloid’s moniker.

It was a nod to Massachusetts’ most beloved couple, JFK and Jackie, a catchy shorthand for all the things Chuck and Carol had come to embody in the press: goodness, promise, purity, tragedy.

To white suburbanites in particular, already awash in warnings about the dangers of the “inner city,” Carol’s murder was a terrifying warning.

“Any one of us can become victims,” one of Carol’s friends said on the news. “It can be a relative of mine. It can be a relative of yours. It can literally be everyone.”

It was Oct. 28, five days after the shooting. Onlookers gathered outside the Medford church where Chuck and Carol had married, and where Carol was now being eulogized.

Inside, it was standing-room-only. Mayor Flynn was there, along with the police commissioner and the governor of Massachusetts, Michael Dukakis. People wept quietly through the whole service. But the emotional climax came when Chuck’s best friend climbed up to the podium and unfolded a note that Chuck, unable to attend because of his injuries, had written from his hospital bed.

“Goodnight, sweet wife, my love,” the letter began. “God has called you to his hands.”

The letter was short. Chuck didn’t have the strength to pen much more. He called on people to forgive the killer, as God would forgive.

“Now you sleep away from me. I will never again know the feeling of your hand in mine. But I will always feel you,” he wrote to Carol. “I miss you. And I love you. Your husband, Chuck.”

00:00

00:00

A long silence followed. Then, from the pews, a single strangled cry.

A few days later, Carol’s and Chuck’s baby boy died. Christopher William Stuart was 17 days old when he took his last breath. He was buried next to Carol.

Every day, in the hospital room where he wrote his letter to Carol, Chuck had been growing stronger.

And so, on Oct. 26, two days before the funeral, Detectives Ahearn and Tinlin had finally been allowed into the Boston City Hospital ICU to interview him. Until then, Chuck had been too heavily medicated to talk — the bullet had ripped through his liver and intestines, missing his aorta by a fraction of an inch.

Still, Chuck’s doctors had warned the detectives to keep their visit brief. So they stuck to the basics: What happened? Who did it?

Chuck told them what he could remember. The shooter was 28 to 34 years old, 5’10”, gaunt, with high cheekbones, a short afro, shaggy facial hair, and a raspy voice with a singsong tone. He’d gotten in the car and told Chuck not to look in the rearview mirror. He demanded money, then called Chuck “5-0”— street slang for police — and started shooting.

Chuck was still on a lot of pain medication. His voice was flat, monotone. He got tired fast, and the detectives called it.

As the Bobbies walked out of the hospital, they stopped in the entryway and looked at each other.

He remind you of anyone? one of them asked.

Advertisement