This story is best experienced with audio.

It was 1989. The crack epidemic was raging, the murder rate was soaring, and white flight had taken hold.

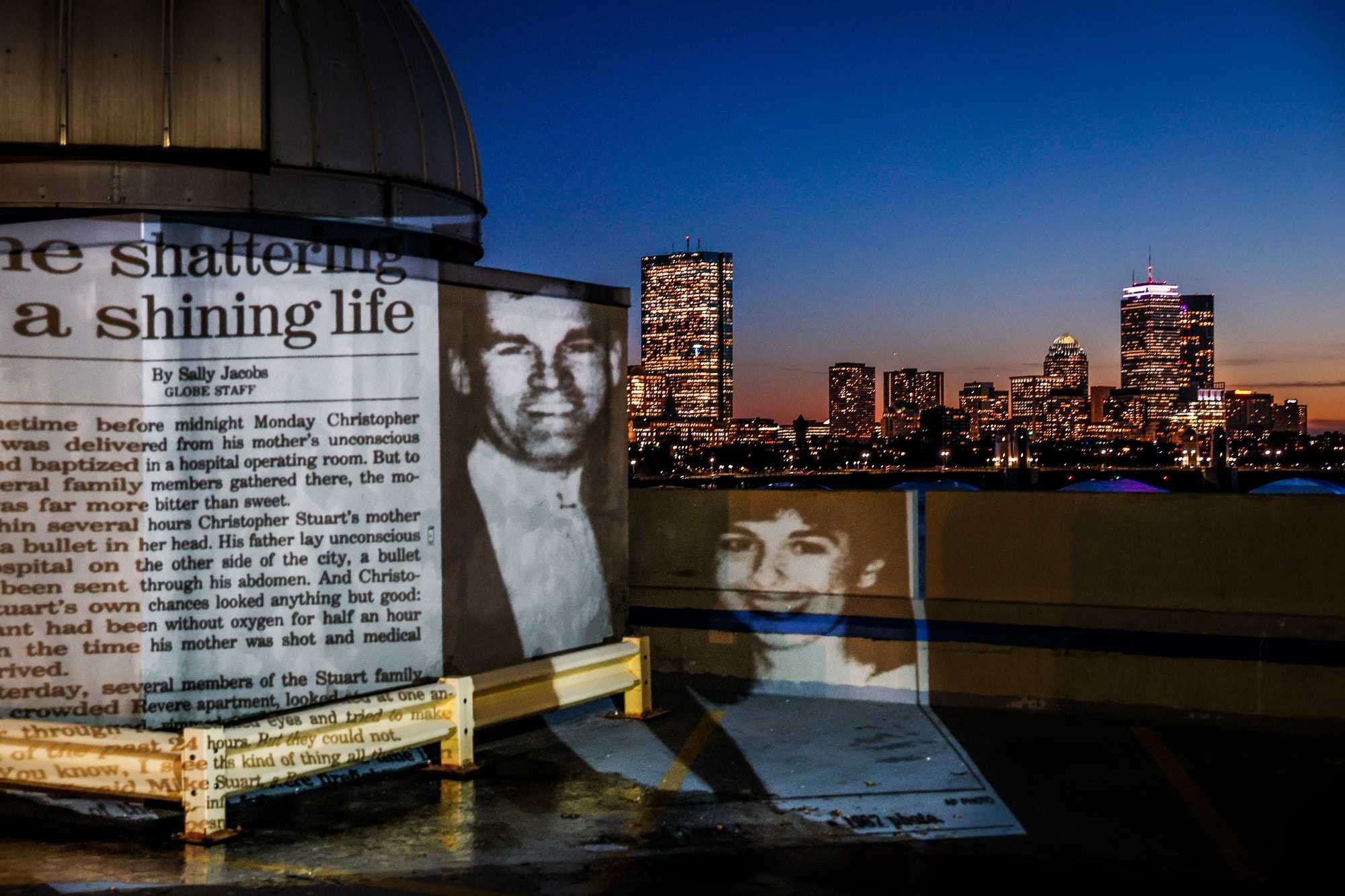

Then came a shooting that would go on to define so much about Boston: its identity, its politics, its problems.

This is the untold story of Mission Hill, the Charles and Carol Stuart shooting, and the people who got caught up in it and never managed to get free.

The Charles Stuart Case:

Chapter 1

The untold story of the Charles and Carol Stuart shooting

The voice on the 911 line was strained, with an edge of panic.

“I’ve been shot,” the man said. There were no sounds in the background that offered any clues to what had taken place. Just the low, steady static of the recorded line.

“Where is this, sir?” asked the dispatcher, who scribbled on a notepad as the wheels of a reel-to-reel recorder captured each dramatic breath and pause.

“I — I have no idea,” the man stammered.

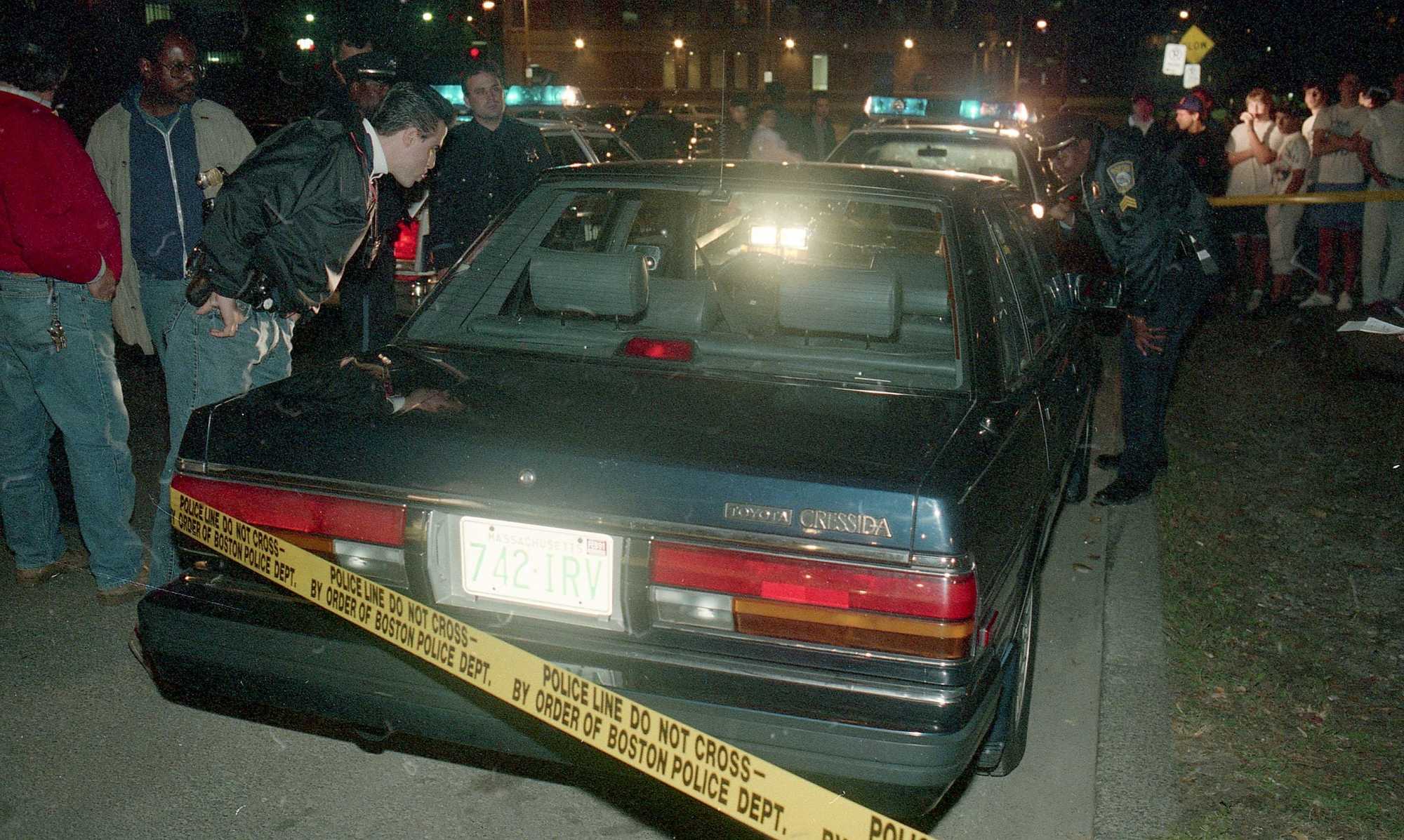

It was 8:43 p.m. on the night of Oct. 23, 1989. The man’s name was Charles Stuart, but everybody called him Chuck. He was lost somewhere in Boston, calling from the brick of a car phone installed in his blue Toyota Cressida. He wasn’t alone.

His wife, Carol, sat in the passenger seat next to him. She was seven months pregnant with their first child. And Chuck said Carol was in bad shape.

The dispatcher looked up from his notes and signaled to a sergeant — two fingers, two victims.

The sergeant grabbed another phone to listen in. He pulled the spiral phone cord tight, and wedged the handset between his ear and shoulder.

“I was just coming from … Brigham and Women’s Hospital,” said Chuck, stumbling over the words.

His voice carried just a hint of a Boston accent, like something he’d tried to leave behind. He sounded white, educated, and polite. He and Carol had been heading home to the North Shore from a birthing class. Chuck said a man jumped into his car and told him to drive.

“He made us go to an abandoned area,” Chuck said. He was talking in scattered sentence fragments now. He panted and moaned.

The dispatcher pushed him to describe his location — anything, a cross street, a building — but Chuck was fading.

“I don’t know. I don’t see any signs,” Chuck said. “Oh, god.”

But the dispatcher was starting to piece it together.

Chuck and Carol had left Boston’s premier labor and delivery hospital two, maybe three minutes before Chuck dialed 911. They had steered their car out of the parking garage and hit Huntington Avenue — which was both a busy city thoroughfare and a dividing line that separated one world from another.

Stay north of Huntington, and you get world-class hospitals, the Museum of Fine Arts, Harvard Medical School — some of the renowned jewels of Boston.

But head south, and you cross into the Roxbury neighborhood of Mission Hill, where crack dealers prowled, cabbies refused fares, and white suburban couples simply did not go.

Chuck told the dispatcher that the man got into his car at Francis Street and made him drive straight across Huntington. Chuck had crossed that line, with Carol and their unborn child in tow.

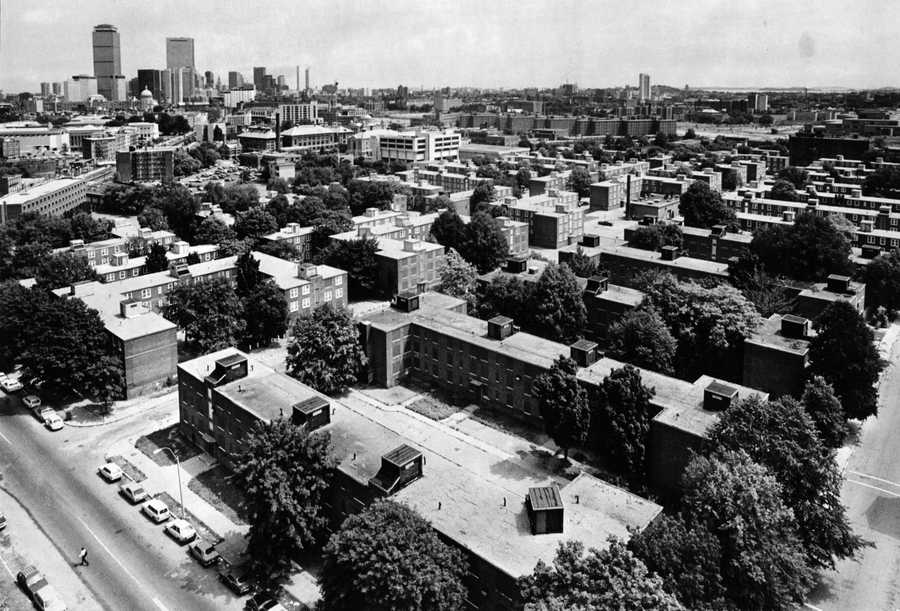

The couple’s Cressida zig-zagged through a maze of blocky brick buildings, vacant lots, drooping chain link fences, and skinny one-way streets of the Mission Hill public housing complex.

“Has your wife been shot as well?” the dispatcher asked.

“Yes,” Chuck said, quickly now, like he was forcing the word out between short, shallow breaths. A long pause followed. One second, two seconds. Then, Chuck again, his voice faltering, added: “In the head.”

Chuck and Carol Stuart’s fateful drive through the heart of Mission Hill that night would come to define so much about Boston: its identity, its politics, its problems.

But Chuck didn’t know that — not yet, and probably not ever. The police dispatcher had no idea. The sergeant was thinking only of this moment, not of posterity. This single 911 call would change the course of countless lives, and the history of the city itself. Recovery would take years, and for some, it would never come.

In just a few hours, the story of this night would be beamed in near-real time onto TV sets in living rooms across the country; it was a time before 24-hour cable news had numbed viewers to such spectacles. It would touch off one of the most intense police investigations in Boston’s history and cement the city’s reputation as one of the most racist cities in the nation. It would be the subject of books, documentaries, and songs; William Shatner would narrate it, Marky Mark would rap about it.

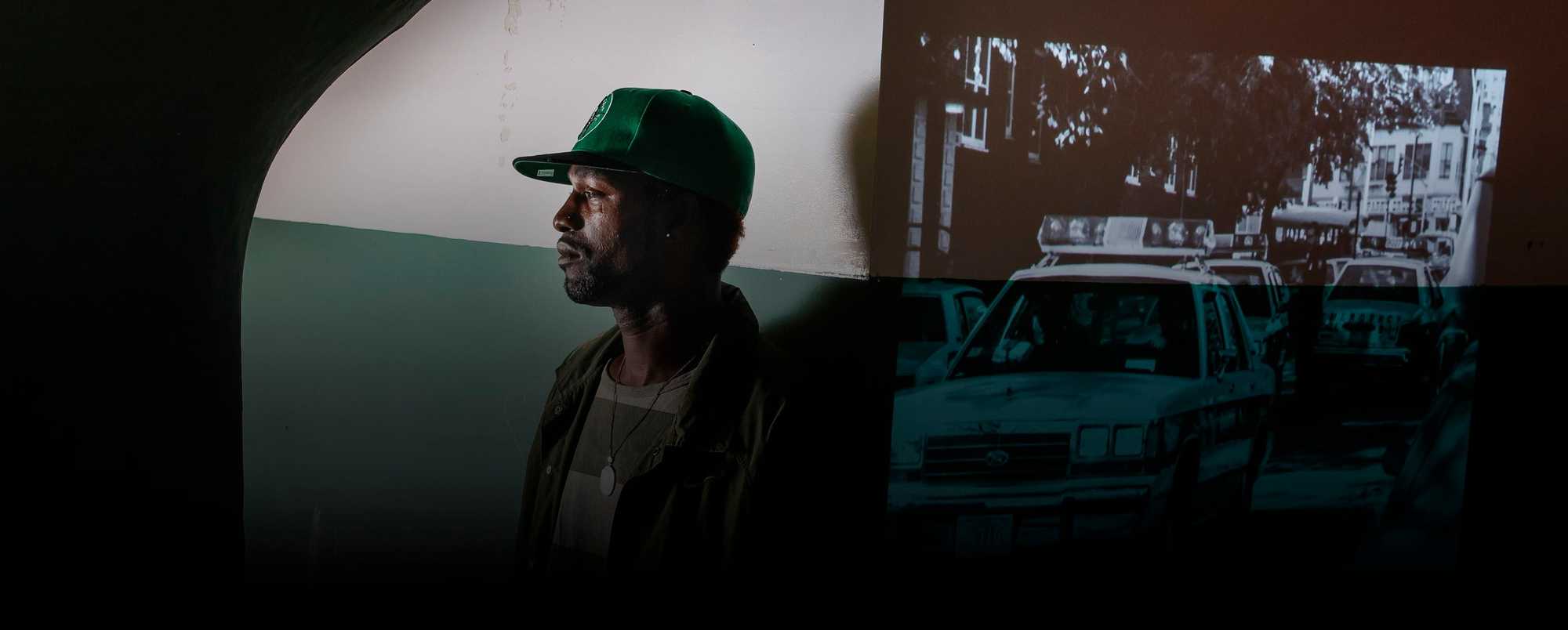

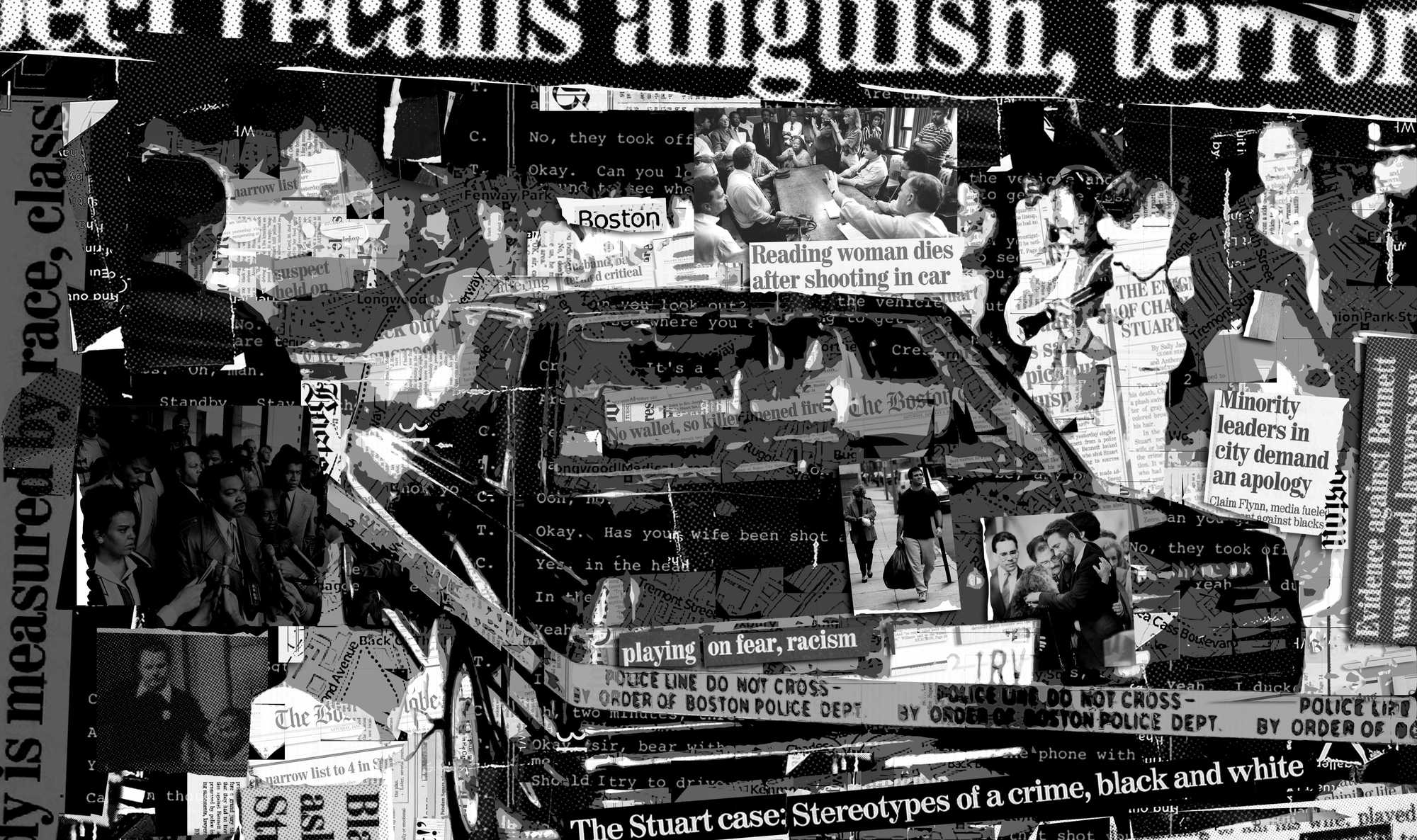

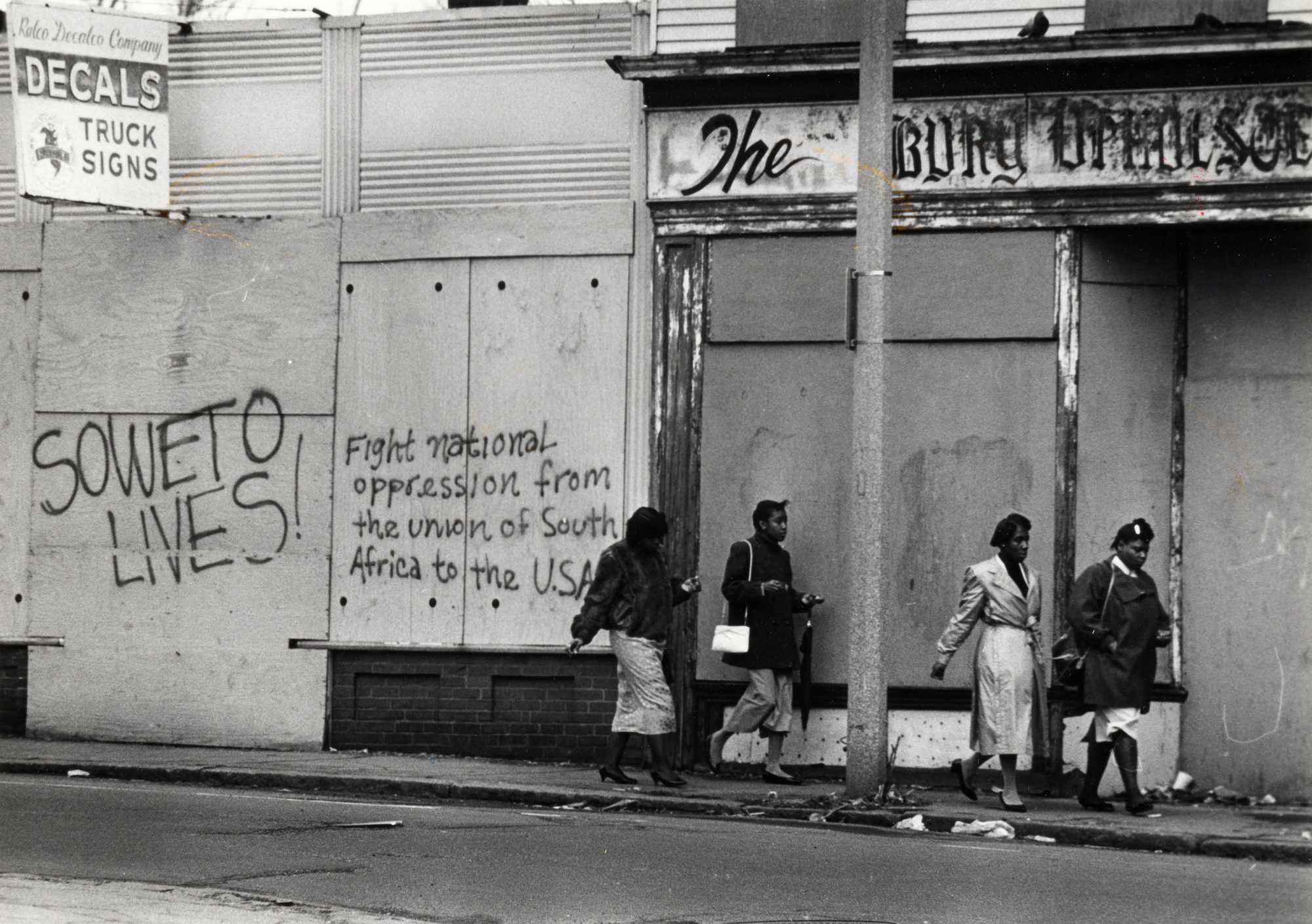

The Mission Hill neighborhood of Roxbury became the epicenter of the Stuart case. From top: The Mission Hill public housing complex in 1984. Two woman walked through Mission Hill in an undated photo. The intersection of Huntington Avenue and Tremont Street in January 1990. (Ted Dully, George Rizer, Evan Richman/Globe Staff)

To most of the rest of the country, Boston was both proudly historic and fiercely — almost comically — parochial. It was the “city on a hill,” home to John Hancock and the Kennedys and a gold-domed State House that shone in the sun. Above all else, it was a city of neighborhoods, each one separate and distinct and none too welcoming to outsiders.

There was the shamrock-tattooed white Irish enclave of Southie, where bar fights broke out over baseball even though the Red Sox hadn’t won a championship in 70 years. There was the tony Back Bay, with its broad boulevards, graceful old trees, and brownstones with wrought-iron fences.

And there was Mission Hill, a neighborhood whose residents — mostly Black and brown and barely scraping by — made up a city within a city. The corners could be tough, but the library and the basketball courts were sanctuaries, and there was always a watchful grandma or big brother around to patch a skinned knee or break up a fight. People looked out for each other here — they had to. Because to much of the rest of the city, Mission Hill was an afterthought.

In fact, so neglected were the people of Mission Hill that in the mid-1980s, some had actually aligned with other castoff neighborhoods to try and secede from Boston altogether, to form a new city called Mandela. The effort had failed, and Mission Hill had returned to its humble station as lazy TV news shorthand for urban violence.

Some, especially those who fall on the wrong side of this story, may want to write the Stuart case off as ancient history. But to many others, it’s living history. Today, the case is long gone from the news, but it never did disappear. It’s a trap door waiting to swing open.

Sit down to play dominoes against the old man who drinks Coronas in the park, and say the name “Chuck Stuart” — you’ll see the memory rise in real time. It’s all right there, just below the surface. Ask others and you’ll get a heavy exhale. “That case ruined my life,” one man says. “I’m not talking about that,” says another.

But, you knock on the right door? Someone will open it, and they’ll say: “Finally.” It’s time.

You may have heard the story of Chuck and Carol Stuart in Mission Hill. You may think you know what happened.

But you don’t. Because the story that’s long been told, taught, or passed down through generations? It’s way off.

Amid the tense conversation and push-and-pull of Boston of today and yesteryear, in the wake of an extraordinary national discussion about race, policing, and media coverage, and during the city’s renewed season of self-reflection, a team of Boston Globe reporters spent more than two years reinvestigating the Stuart case.

Reporters spoke to hundreds of people who were involved in it in some way — from police and prosecutors to suspects and witnesses to reporters and politicians and bystanders swept up in the frenzy. We assembled thousands of pages of documents, photographs, audio recordings, and videos, pulling them from courthouses and archives and the basements of long-retired people who could never quite let the case go.

We found a conspiracy that was bigger than anybody knew, and identified dozens of regular people — people who would have called themselves good, upright, law-abiding citizens — who helped to hide the truth. The police weren’t just fooled, they were careless and complicit. The media had doubts, but squashed its skepticism because a sensational story had already taken root.

Then, there is the crime itself: It was never really solved. Police and prosecutors ultimately named one gunman — but the Globe team uncovered evidence that suggests they may have gotten it wrong.

It’s been more than three decades; much of Mission Hill has been torn down and rebuilt and filled with college kids who shake their heads “no” when you ask them if they ever heard of Chuck and Carol Stuart. A whole new generation of police and politicians has arrived to push this city forward. But, whether they know it or not, they push against the weight of what was unleashed on the night of Oct. 23, 1989.

This is the untold story of Mission Hill, of the Stuart case, and of the people who got caught up in it and never managed to get free.

The only sound on the 911 line was Chuck’s labored breathing. Someone on the line, maybe a dispatcher, said, “I’ve lost him.”

But then, the officers and dispatchers on the line noticed another noise in the background of the call.

“Hey, wait a minute,” one of them said. “Can you hear the sirens?”

00:00

00:00

By now, police cars across the city had been alerted to the situation that was unfolding. Officers were flipping on their sirens and speeding toward Mission Hill, the whoop-wails rising then falling, closer and closer.

Police blue lights were common in Mission Hill in these days, almost routine — the city’s murder rate was nearing an all-time peak. But this crime — the carjacking of a man and his pregnant wife — shattered that routine.

For just a few more minutes, the people of Mission Hill were oblivious to the gathering storm.

In a high-rise hallway on a nearby street nicknamed Assassination Road, a group of teenage boys smoked a joint and passed a bottle of sweet liquor, laughing at their own jokes. They didn’t notice the sirens, not at first anyway.

A few blocks away, an 18-year-old girl curled up on her bed in her mother’s little apartment, listening to music and waiting for her boyfriend to come home. Weeks later, they would find themselves on the wrong side of a police interrogation room table.

Elsewhere, a clueless teenager dumped a stolen car at the curb and started walking toward home. And an 11-year-old boy stood in his warm kitchen, looking over his mother’s shoulder as she played spades at the table. Soon, a knock would come at the door.

Note: Street names and landscapes have changed slightly since 1989, so some locations on this map are approximate.

Brigham and Women's Hospital

Charles and Carol Stuart attended a birthing class here on Oct. 23, 1989.

As the sirens multiplied, a vast machinery switched on. Police dispatchers sent messages out into the night; the messages started to reach politicians and the media.

And on a little side street that was about to fill with detectives, a woman left her home to walk to the corner store. She barely noticed a blue Toyota Cressida coasting by, with a white man at the wheel. She was thinking about her lottery numbers. She was hoping to get lucky.

Like the rest of Boston’s nearly 600,000 residents, the people of Mission Hill were focused on the matters of the moment. Soon enough, they would find themselves pulled into the crime that would leave an indelible mark.

Back at police dispatch, the authorities were starting to panic. Where was Chuck?

Then someone figured, if they could hear the sirens over the 911 line, it meant that one of the police cruisers was close. They just had to figure out which car.

Now, the radios in the cruisers crackled with a new directive. “All units, shut off your sirens.”

In the sudden quiet that followed, dispatch ordered one cruiser at a time to sound its siren, and waited to hear the corresponding wail on Chuck’s open 911 line — like some kind of big-city sonar.

And, finally, a siren howled and the radio crackled back to life: “Bravo, 4-1-2. McGreevey Way and St. Alphonsus Street. I got ‘em down here.”

00:00

00:00

Relief flooded the dispatch room, and what felt like a city’s worth of cops descended on a previously obscure corner of Mission Hill.

The final question captured on Chuck’s 911 line before dispatch hung up was, in the moment it was asked, completely unremarkable. It’s only in hindsight, after everything that happened, that it sounds prophetic.

“Have you gotten any calls from the press yet?” a dispatcher asked a colleague.

The late shift photographer for the Boston Herald had been tooling around Roxbury in his car, listening to the police scanner, waiting for something to happen.

It had been a quiet day, but Evan Richman didn’t expect it to stay that way. It never did. There was a shooting almost every night — and it was his job to document them.

Evan was only a few years out of college — this was his first job at a big city newspaper — and every time he showed up at a crime scene, he felt jangled by the chaos and the grief. The blood on the ground, the broken glass, the stricken relatives in sweat pants and housecoats.

The scanner in his car was never really quiet, but its coded chatter had a distinct rhythm. And now, just before 9 p.m., the rhythm changed. Police dispatch was asking patrol cars to turn off their sirens. Evan had never heard that before.

Curious, he tried to steer his car in the direction of the street names the scanner rattled off: Longwood, Huntington, Tremont. He had no idea what he was driving toward — information transmitted over the public-facing radio was deliberately cryptic. But then, he heard an officer announce, “I got ‘em down here.”

Evan was only a few blocks away. Almost instantly, an ambulance threw on its siren and swerved around him. He followed.

He saw pandemonium ahead. He parked his car, grabbed his camera, and ran. The street was jammed with cruisers and ambulances, people poured out of their apartments to watch. Some kind of film crew circled the EMTs, pointing a camera and a bright light.

All eyes were locked on a blue Toyota Cressida parked at the curb.

Evan raised his camera and looked through the viewfinder. He wasn’t there to study the scene. He was there to make pictures, which, in the world of cutthroat daily journalism, is a different thing. Boston was a two-newspaper town, and the Herald was the tabloid underdog to the bigger and more cosmopolitan Boston Globe. The competition between the two papers was ferocious, and the Herald consistently beat the Globe on breaking news and crime. Every night, that’s what Evan chased. There was a circulation war, and a good crime scene photo could win a battle.

Evan positioned himself right in front of the car, facing the windshield, and clicked the shutter. He was focused on the technical elements of photography: the composition of the frame, the contrast, the exposure. He saw EMTs leaning in the front windows, and he liked the symmetry of the shot.

Then, the EMTs rushed past him pushing two stretchers. They loaded the stretchers into separate ambulances, slammed the doors, and sped away.

Just like that, it was over.

Evan still didn’t really know what happened, other than the fact that a white man and woman had been shot in a Black neighborhood. But he didn’t stick around to find out — it just didn’t seem like a particularly remarkable call. Another photographer took his film back to the Herald to be developed, and Evan went back to his car to wait for the next one.

A pair of Boston homicide detectives pulled up to the crime scene in their unmarked car and got out, just down the street from where Evan’s car had idled.

The Stuarts’ Cressida was empty at the curb, keys still dangling from the ignition. Chuck’s car phone — a real commodity in the late ‘80s — lay in the driver’s side footwell. Chuck and Carol were gone, rushed off to different hospitals. Things weren’t looking good for either of them.

Word had spread among the police on the scene that doctors at the Brigham had cut the baby out of Carol’s belly, in a desperate attempt to save his life. They hadn’t given up yet on Carol, but she had been shot point blank in the back of the head. “God bless them,” said one officer over the radio. “I hope they make it.”

Chuck was in surgery, but he’d had just enough strength as the EMTs hauled him out of his car and onto a stretcher to croak out the barest description of the man who had shot him.

“Black,” he groaned. “Man.”

00:00

00:00

The officers surrounding him in the back of the ambulance had peppered him with questions as his voice grew faint. What’d he have on for clothing? Black running suit. Stripes? Red.

Now, the patrol officers who had taken that description walked over to the detectives to relay the facts as they knew them.

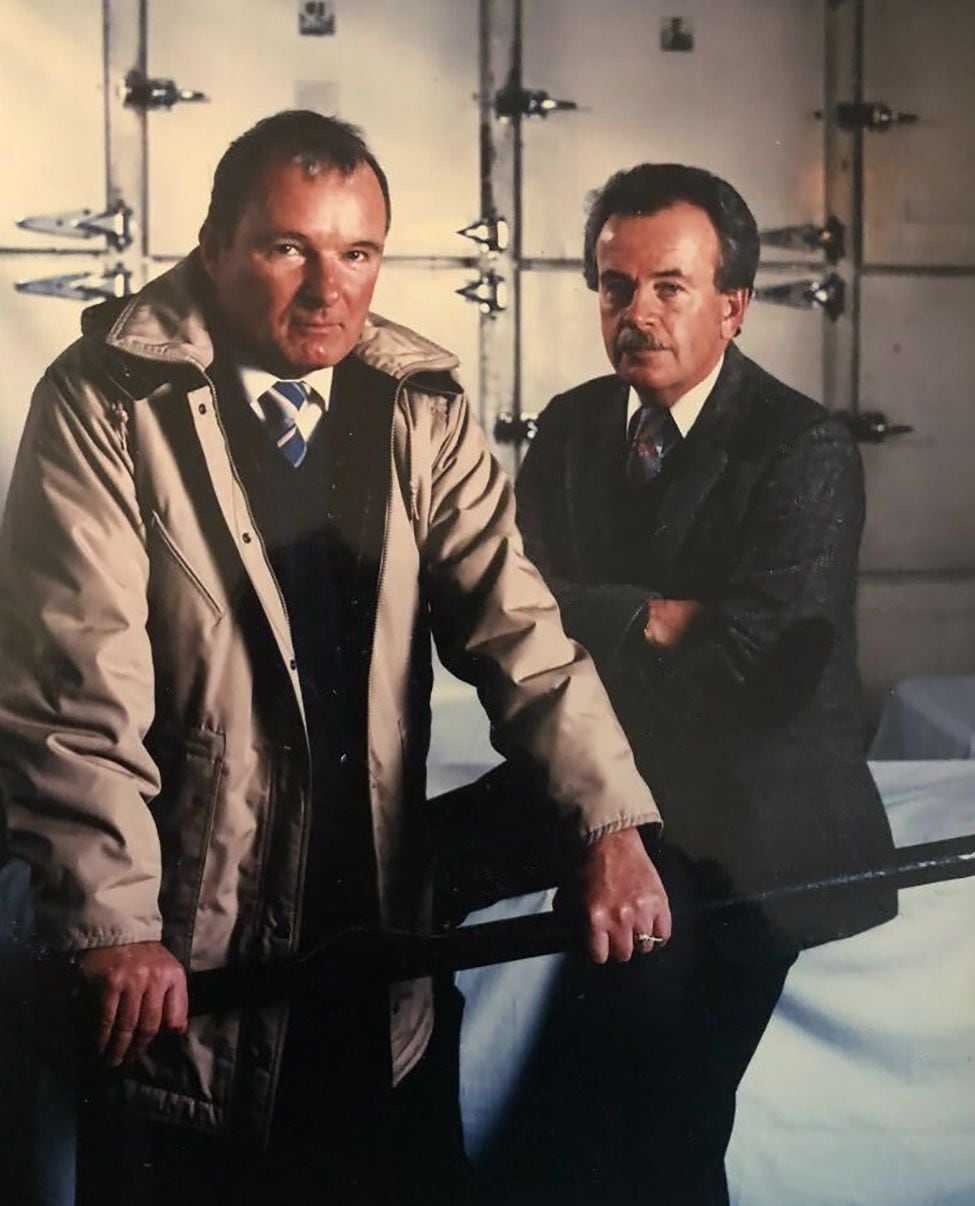

Robert Ahearn and Robert Tinlin were two of the best detectives on the force. Bob and Bob — former Navy men nicknamed “the two Bobbies,” who managed to solve almost every single case they caught. Ahearn was ruddy faced, with a salt and pepper mustache, a raucous sense of humor, and Jordache jeans; Tinlin was quieter, the “bad cop” to Ahearn’s good, a chameleon at home in both leather jackets and sweater vests. Together, they were a formidable team, and they worked out of a little box of an office in the homicide unit on D Street in Southie, under an autographed poster of the rumpled-but-brilliant TV detective Columbo. “I love it when they lie to me,” Tinlin liked to say about their suspects.

And the Bobbies saw a lot of suspects. These days, everybody in homicide was picking up a case a week, if not more. Crack had arrived in Boston just a few years earlier, and most of the shootings in the city now were gang- or drug-related. Most of the victims — and the killers — were young Black men. Most of the detectives, including Ahearn and Tinlin, were white.

Tonight’s shooting belonged to the Bobbies. But within minutes of receiving the call that sent them to the scene, they knew it wasn’t like any other shooting they had ever worked.

The head of BPD homicide was calling in all available detectives. The command staff was ringing up Mission Hill beat cops at home. The mayor himself was on his way to the hospitals to visit the victims.

This shooting had picked the city up and tipped it over, spilling its pieces in a jumble onto the streets of Mission Hill.

In this moment, in the late fall of 1989, Boston was a deeply fractured place.

It had strict liquor laws left over from the Puritans; neighborhoods whose borders defined the lives of the people inside them; civic leaders who wanted to portray the city as a progressive beacon.

Boston called itself the cradle of liberty, but it was just as famous for its racism.

Fifteen years earlier, the city had exploded into the national consciousness with widespread violence and unrest over school desegregation. In 1974, a federal judge ruled that Boston was running two different school systems: one for white kids, and one for Black kids, and ordered the city to integrate. That decision — to send Black children to white schools and white children to Black schools on yellow school buses — came to be known simply as “busing.”

00:00

00:00

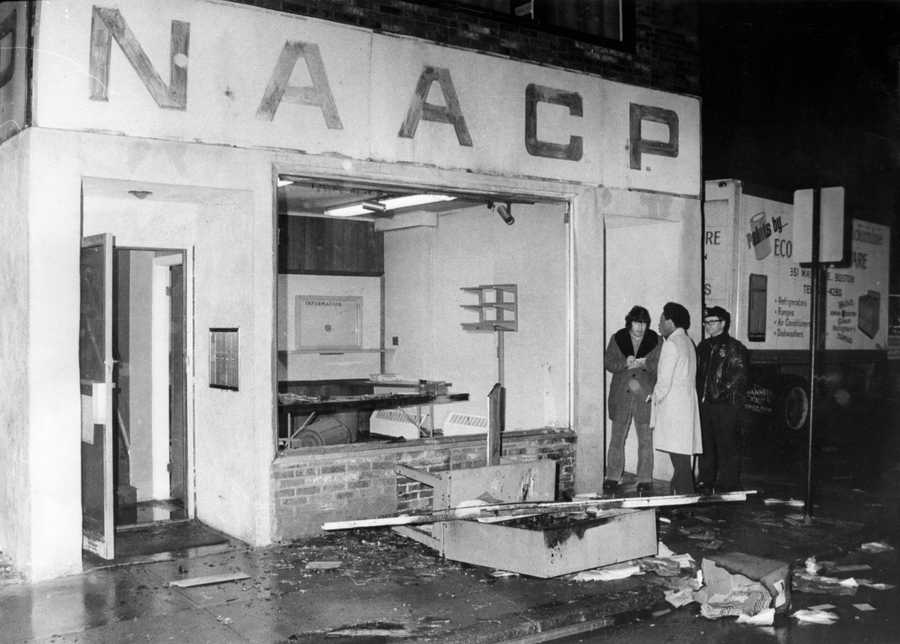

Busing set off bursts of violence that would last years. The city’s NAACP headquarters was firebombed; roving mobs beat people in the streets; students stabbed each other in the high schools. The Ku Klux Klan came to town. The National Guard was called in. TV sets across America glowed with shocking videos of white parents whipping rocks and bottles at buses full of Black children.

By the end of the ‘70s, the violence had ebbed, but the city’s reputation was made. The ‘80s brought efforts to heal, but there remained a deep schism between Boston’s white citizens and Black citizens, and the two groups regarded each other with hostility.

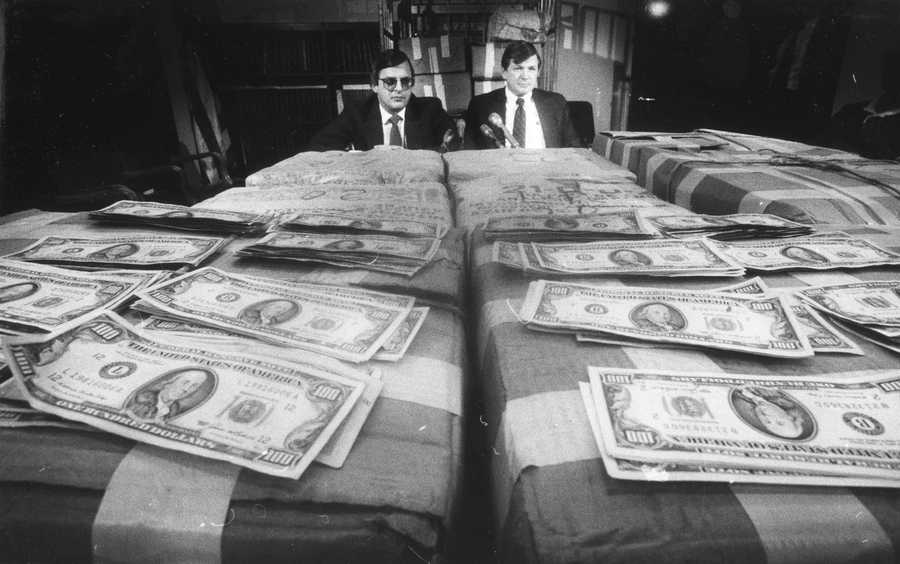

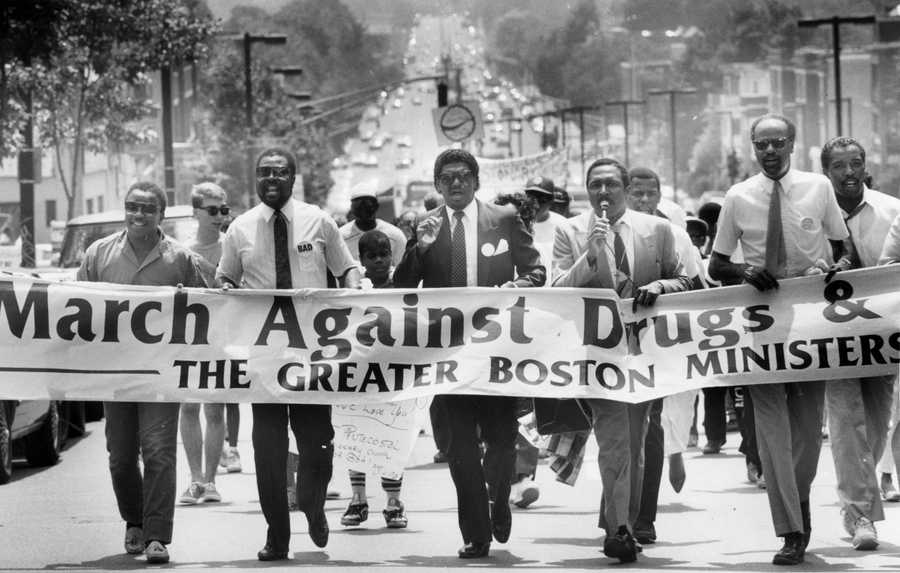

And as the ‘80s rolled on and the crack epidemic swept America, the rhetoric in Boston and across the rest of the country about race and crime grew more and more pitched. You could hear it in the speeches from the politicians and the breathless newscasts from the TV reporters: Everything was war, war, war.

A woman gestured for students being bused home to Roxbury to "go home and stay home," as a school bus left Patrick F. Gavin Middle School in South Boston on Sept. 17, 1974, during the first full week of school under the new busing system put in place to desegregate Boston Public Schools. (Charles Dixon/Globe Staff)

There was the war on drugs and the war on crime and the war on gangs and the war on welfare fraud and the war on dirty lyrics. There were the young Black men in Starter jackets sitting on stoops blasting hip-hop out of their boomboxes, “Fight the Power” and “F**k tha Police.” These were the days of white flight; of the myth of the crack baby; of the coming of the super-predator.

“Our most serious problem today is cocaine, and in particular crack,” President George H.W. Bush told the country. “Who’s responsible? Everyone who uses drugs, everyone who sells drugs, and everyone who looks the other way.”

00:00

00:00

In the spring of ‘89, a gang of Black and Latino boys was accused of savagely raping and beating a white woman jogging through Central Park, and America discovered yet a new terror: “wilding” — random attacks by Black teens. The story was false, but the truth took decades to catch up.

“We must face the truth which the headlines coming out of big cities from New York City to Los Angeles tell us,” Boston Mayor Raymond Flynn had warned at the beginning of the summer of ‘89. “America’s cities are in deep trouble.”

And now Flynn’s city was in trouble.

When Chuck Stuart dialed 911 that October night, he could barely speak, but it didn’t matter. He was telling a story that every American child — white, Black, or brown — grew up hearing:

A Black man did it.

This was the atmosphere in which homicide detectives Ahearn and Tinlin surveyed the scene one last time, before heading to the Roxbury district police station.

The sidewalks around them were filled with people from the neighborhood — young women with plastic rollers in their hair; men in colorblocked windbreakers with baseball caps pulled low over their eyes; skinny kids in high-tops and oversized T-shirts.

They were almost all Black. Chuck’s description could fit a dozen of them, maybe more, easily.

Police flashlight beams strobed up and down the streets. The crowd murmured and jostled; the cops barked at anybody who got too close. Everyone eyed each other warily. They could feel it in the air: The hunt had begun.

Carol Stuart died at 2:50 in the morning, on Oct. 24, 1989. She was 30 years old.

She had already chosen a name for her son, Christopher. He had been delivered by caesarean section and rushed to the neonatal intensive care unit. He was 10 weeks premature, and he had been without oxygen for a long time, but he was alive. He had dark hair and brown eyes, like his mother.

The police held a late-night press conference at the Roxbury station to announce that the investigation was already in full swing.

“We have a full investigation underway,” a deputy superintendent in a dark gray suit told a gaggle of reporters. “We have no suspects in custody. We do have a good description of the assailant.”

The superintendent stood shoulder to shoulder with a glowering Mayor Flynn, who looked like he’d rolled out of bed in a bright green warmup suit.

“It’s a tragic situation, that everybody’s heart goes out to the family. And it’s another example of the availability of guns,” he said. “Police officers have got the most difficult job in society today — they’re out there trying to fight a war and win a war on drugs.”

Flynn said he had just talked to the police commissioner, and they’d come up with a plan.

“I’ve asked him to put every single available detective in the city of Boston on this case to find out who the people or person who is responsible for this cowardly, senseless tragedy,” Flynn announced.

00:00

00:00

A few hours later, the coroner performed Carol’s autopsy. In his report, he cataloged every detail of her body. Brown eyes, good teeth, red-painted fingernails. Purple-red contusions around the eyelids and bluish purple bruising on her right arm.

The last pages of the report are diagrams of Carol’s body and fragments of jotted notes. “If she was looking at him (problem),” the coroner wrote. “If hand up…”

He drew a picture of the bullet’s path through Carol’s skull, and some question marks.

When the sun rose over Boston the next morning, newspaper boxes across the city displayed the crime scene photo taken by Herald photographer Evan Richman.

It ran on the front page, under the headline: ‘A terrible night!’

In Dorchester that morning, the metro editor for The Boston Globe had just sat down to eat a breakfast sandwich at Burger King, when he looked out the window at the two newspaper boxes on the street and noticed something strange.

Pedestrians were walking right past the green Globe box. But they were stopping short when they hit the yellow Herald box. They were fishing in their pockets for a quarter, buying the Herald, and staring with open mouths at the cover. What the hell? the editor thought. He abandoned his breakfast and went to investigate.

There, in black and white of the Herald, were Chuck and Carol. Chuck was in the driver’s seat, grimacing. His white dress shirt was unbuttoned, exposing his chest and stomach. His back was arched in pain.

Next to him was Carol, slumped sideways over the swell of her pregnant belly. She was leaning against her husband. Her hair fell across her face. Her mouth was open, and dark with either shadow or blood.

The Globe editor saw it and stopped breathing. He knew right there — nothing was ever going to be the same.

Advertisement