Gen Z in the Boston area

The Globe talked to dozens of Bostonians under the age of 25 and asked them about their financial goals.

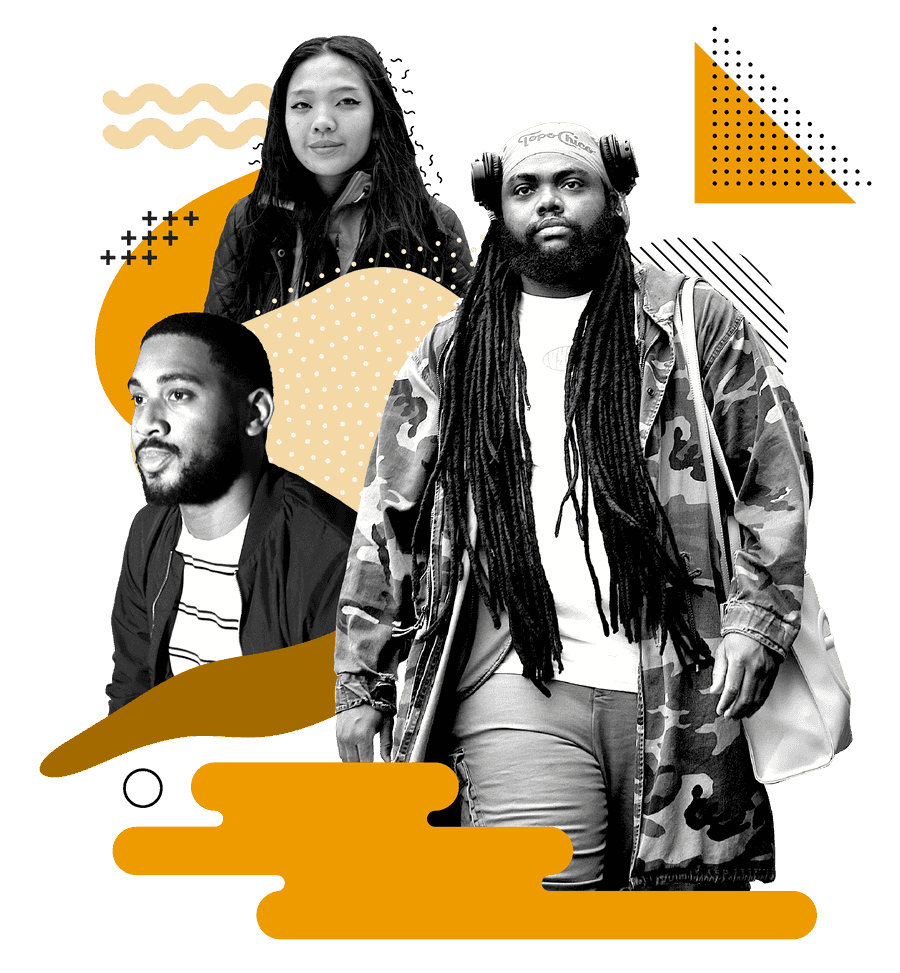

Fiona Phie

They/she, 23, East Boston

Occupation: Nonprofit program coordinator, visual artist, DoorDash driver, employee at a boba cafe

They put 40% of their income towards the goal.

Nate McLean-Nichols

He/they, 25, North End

Occupation: Musician, youth mentor

He puts at most 15% of his income towards the goal.

Miles Johnson

He/him, 23, Arlington

Occupation: Civil engineer

He puts 15% of his income towards the goal.

Every day in high school, Fiona Phie would wave to an elderly woman who sat on the stoop of her single-family home in East Boston. The woman eventually died, and Phie watched the property go through a life cycle that has become all too familiar: A developer bought the house, razed it, and built luxury apartments that rent for more than Phie’s family makes in one month — within two years.

“Just like that,” said Phie, who uses they/she pronouns. “It happened so fast.”

It makes Phie feel hopeless about a dream they have of homeownership and envious of what their parents once had. The Phies emigrated from Indonesia in 1989 and purchased a home in Eastie’s Central Square for $170,000 with money they earned selling flowers at the Wellington MBTA station. Now Phie’s mother frequently receives letters from corporations offering to pay $1 million for the house.

How can I ever compete with that, Phie wonders?

The 22-year-old lives at home rent free, so almost half of Phie’s monthly income from multiple jobs — nonprofit coordinator, visual artist, Doordash driver, boba barista — is funneled into savings. (Phie’s income fluctuates widely; last year, it was just under $50,000.) The hope? To squirrel away enough for a 25 percent down payment. But that goal becomes less attainable by the day.

Mortgage rates doubled in 18 months. Prices are not relenting. Wages can’t keep pace.

Phie feels like they could save $20,000 in a calendar year. But by the time January rolls around again, homes are $20,000 more expensive.

“It’s like, no matter what I do,” Phie said, “I’m back to where I was a year ago.”

Many members of Gen Z identify with that sense of being stuck: The closer they get to buying a home, the further away it feels. Like a flea perpetually stuck in honey, one said. Like an astronaut hurtling deep into space, added another.

Buying a house around here, especially in your 20s, has always been a monumental task. But according to a study in November by mortgage company Freddie Mac, one third of Gen Z in the United States believe that homeownership will always be out of their reach. And renting is scarcely better. Gen Z can expect to spend $226,000 on rent in their lifetimes, adjusted for inflation — about $24,000 more than millennials and $77,000 more than baby boomers, according to real estate marketplace Hotpads.

That has set Nate McLean-Nichols back. As a child, he shuffled between apartments in Roxbury and Dorchester, spending a few years in each until his family was either priced out or evicted. Now he is the breadwinner, making more than $40,000 a year as a musician, and sharing a two-bedroom in the North End with his mother, whose illness precludes her from working.

More than 70 percent of his salary goes to the $2,800 in rent and utilities, plus unexpected medical bills. It leaves him with $200 in spending money, which he uses to buy concert tickets and merchandise from other musicians. He tucks away a smidge of that for the condo he hopes to someday buy through the city’s preferential housing program for artists. The struggle gnaws at him. McLean-Nichols has musician friends who have moved elsewhere, to Philadelphia or Baltimore, settled comfortably, and never looked back.

“They’re making money in the business,” he said. “I’m losing money paying rent. What needs to be done here is that there needs to be a more intentional effort on infrastructure and hospitality. Hospitality to me is not just about welcoming people. It’s about making the changes necessary so folks want to stay in Boston.”

Miles Johnson already knows Boston is not his forever home.

He moved to Arlington in 2021 from the South for a job in civil engineering, enamored by New England’s promises of seaside views and that “intellectual” environment for which we are so often touted. Then the rent hit him, and the realization that the check he cuts his landlord dwarfs many mortgages in Atlanta and Charlotte.

Johnson, whose annual salary is in the upper five figures, understands the “why” of the situation. Basic supply and demand, he said. He is far from the only person hunting for a one-bedroom in Jamaica Plain or Roxbury, desirable neighborhoods closer to the culture and the T lines.

But five or 10 years down the line, the appeal of Boston blurs. He’ll live here for a while, find his tribe, and perhaps go to graduate school. When it comes time to settle, Johnson will likely leave.

“It’s simple economics,” he said.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporter: Diti Kohli

- Editors: Tim Logan, Andrew Caffrey

- Photographers: Barry Chin, Lane Turner, David L Ryan, John Tlumacki, Suzanne Kreiter, and Craig F. Walker

- Photo editors: Leanne Burden Seidel and William Greene

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara

- Copy editing: Mary Creane

- Digital producer: Dana Gerber

- Audio producer: Jesse Remedios

- Audience engagement: Cecilia Mazanec and Jenna Reyes

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

© 2023 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC