Boston team

Oct. 27, 2022

Nearly every business in this Iowa town has closed. They won’t give up on the opera house.

WHAT CHEER, Iowa — Judy Striegel is crying backstage, but these are tears of joy.

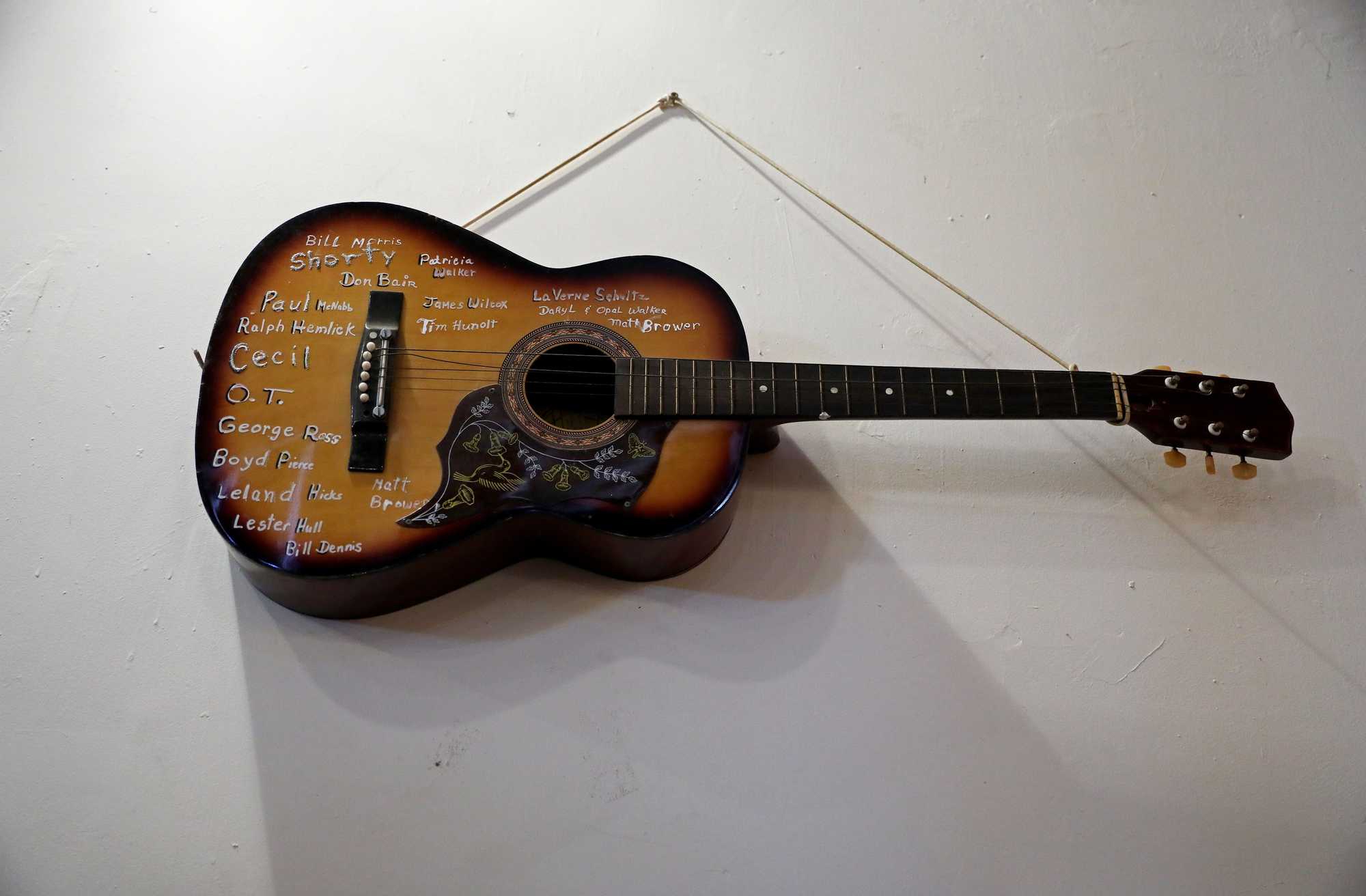

Striegel gets emotional thinking about the neighbors who have helped this 19th-century opera house come to life again: a leaky roof repaired, hazardous knob-and-tube wiring replaced. It’s starting to look like what it could be, with spiderwebs cleared off red velvet curtains and new planks of wood replacing soft patches of floor.

You have to squint to see the future here, but she has no problem with that.

Decades ago, thousands lived in the former coal town of What Cheer (pronounced watch-ear); now, the population has dwindled to about 700. The old opera house is among the last surviving businesses and one of few money makers in a place whose past can seem brighter than its present.

On North Barnes Street, the mile-long stretch that unites family farms, most everything has closed, though some signs remain on doors, like gravestones. From a distance, you can imagine that Donna’s Diner is still serving up hash browns and eggs, that the storefronts with broken plywood inside still house Marilyn’s Tavern and Wesley Thomas Grocer. Men drive up the stretch in golf carts, or dump coolers full of water in parking lots, or burn garbage in their driveways, whiling away a Wednesday afternoon. Little is open other than Dollar General — the best in the area, a cashier promises — and Casey’s gas station.

But wedged between the shuttered bank and the new one is an opportunity.

Striegel wants to restore the aging but functional opera house to its historic splendor and shape it into a home for the community’s future, with movie nights and school events and as many Saturday evening performances as she can fit on the schedule.

The country-western venue has hosted acts such as John Philip Sousa (1906) and the Texas Tenors (2017). Most importantly to Striegel, the 525-seat theater is where her oldest son performed in high school musicals, and where her mother-in-law wowed with her “beautiful, beautiful voice.” Her third child, Ben, remembers attending plays there as a kid, including some that starred his uncle. (“He’s a better teacher than actor,” he cracks.)

Restoring the venue is as much a personal mission for Striegel as an economic one. “We either do this, or we let it go,” said the 67-year-old with a bob of straight gray hair. “The attachment here is family.”

Beer Belly Barbecue down the way donated 240 meals of pork and brisket for a recent fund-raiser; Eric Coble, the co-owner of the funeral home across the street, gave $1,000 to pay the band. The lighting business in nearby Oskaloosa asked how much more Striegel needed, then wrote a check for $20,000.

In all, $100,000 was raised in just 10 months, a sum that astonishes her still.

Recent stories from the Boston team

Officially, Striegel is retired, but farmers never really retire. She is modest, strong-willed, and soft-spoken at once, a woman who has always done everything and never taken any of the credit. At 35, with four kids living at home, she went back to community college and became a nurse to support the struggling family farm. Striegel spent 25 years in that career, before Ben took over the property — hundreds of acres of corn, soybeans, and cattle a short dirt-road drive off What Cheer’s main street. Instead of turning to a quieter chapter of life, Striegel now pours full-time hours into fixing up the opera house, always ready to drop her errands to take strangers on an hours-long tour of the brick building.

She helped replace a perilous rectangular chunk in the center of the stage, still wobbly after a hole was carved there years ago so a visiting magician could drop through the floor. That was a touchy point for opera house board members, some of whom were involved in the questionable decision to chop up the stage in the first place.

Her commitment to the venue’s original style sometimes trumps her aesthetic sensibilities. (“Us gals don’t really like it,” she confesses of a light fixture in the building foyer, whispering as if to keep the bulbs from hearing.)

Only the third floor, where asbestos lurks beneath the floral tiles, is fully unusable. Green paint is peeling off the walls, and dusty props and mirrors litter the floor. Striegel knows that building an elevator up here could cost as much as $1 million, but nothing feels out of reach. She can see the sunny, high-ceilinged rooms in the back becoming an apartment, perhaps even for an artist-in-residence; the expansive center space once again a ballroom.

They’ll replace what they need and use what they have, like the brown upright piano in the corner with a mercurial middle C.

“As you can tell, history means a lot to me,” Striegel said. “You don’t throw anything away.”

Join the discussion: Comment on this story.

Credits

- Reporters: Julian Benbow, Diti Kohli, Hanna Krueger, Emma Platoff, Annalisa Quinn, Jenna Russell, Mark Shanahan, Lissandra Villa Huerta

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Pat Greenhouse, Jessica Rinaldi, and Craig F. Walker

- Editor: Francis Storrs

- Managing editor: Stacey Myers

- Photo editors: William Greene and Leanne Burden Seidel

- Video editor: Anush Elbakyan

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: John Hancock

- Copy editors: Carrie Simonelli, Michael Bailey, Marie Piard, and Ashlee Korlach

- Homepage strategy: Leah Becerra

- Audience engagement: Lauren Booker, Heather Ciras, Sadie Layher, Maddie Mortell, and Devin Smith

- Newsletter: LaDonna LaGuerre

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Additional research: Chelsea Henderson and Jeremiah Manion

© 2022 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC