Boston team

Oct. 27, 2022

Does a free public transit system sound like a pipe dream? Kansas City is doing it.

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — It takes exactly 43 minutes and 43 seconds for the Main Max bus to complete its full route, squeaking and squelching and rattling from its first stop near the Missouri River to a strip mall 8 miles south.

Climb aboard early on this sun-sweaty Tuesday afternoon and you can watch wilting riders taking their seats, clad in scrubs, return-to-office-ready polos, and many, many Chiefs jerseys. Talk to some of them and you’ll be reminded that public transit woes are a universal frustration. Since Kansas City made all routes free at the start of the pandemic, riders here report using the bus more — but some still have their gripes.

Today, there was the 19-year-old heading home from his shift in the kitchen at Fogo de Chao, who said he probably saves about $200 a year on transit but can’t quite figure out where the extra money goes. And there was a UPS maintenance man happily using his day off to take a free trip to the barbershop (and, briefly, to flirt with an out-of-town reporter).

But there’s also the accountant who complained bitterly about the frequent delays. And the nursing student who needs the bus to get to school but said three or four times a week it doesn’t show up at all.

Recent stories from the Boston team

Michael Herron, 44, joked that he’s “cheap,” a fan of Kansas City’s free museums as well as its free transit. He can get to his job at the dairy in about an hour “if all goes perfectly.” Often it does not.

That lack of reliability is a challenge common to US city transit systems, not the unique result of the fare-free program. Like many of its peers, Kansas City is struggling to hire and retain drivers in a tight labor market. Kansas City is the biggest city in the country with free public transportation, but it isn’t guaranteed past 2023. The buses themselves communicate that uncertainty. “EXACT FARE REQUIRED,” a yellow sign near the door still read. A fare machine stood dormant near the driver.

Ending the experiment could be devastating; most people here don’t have access to a car, and riders say free fares have helped them commute to work, shop for groceries, and see family and friends more frequently.

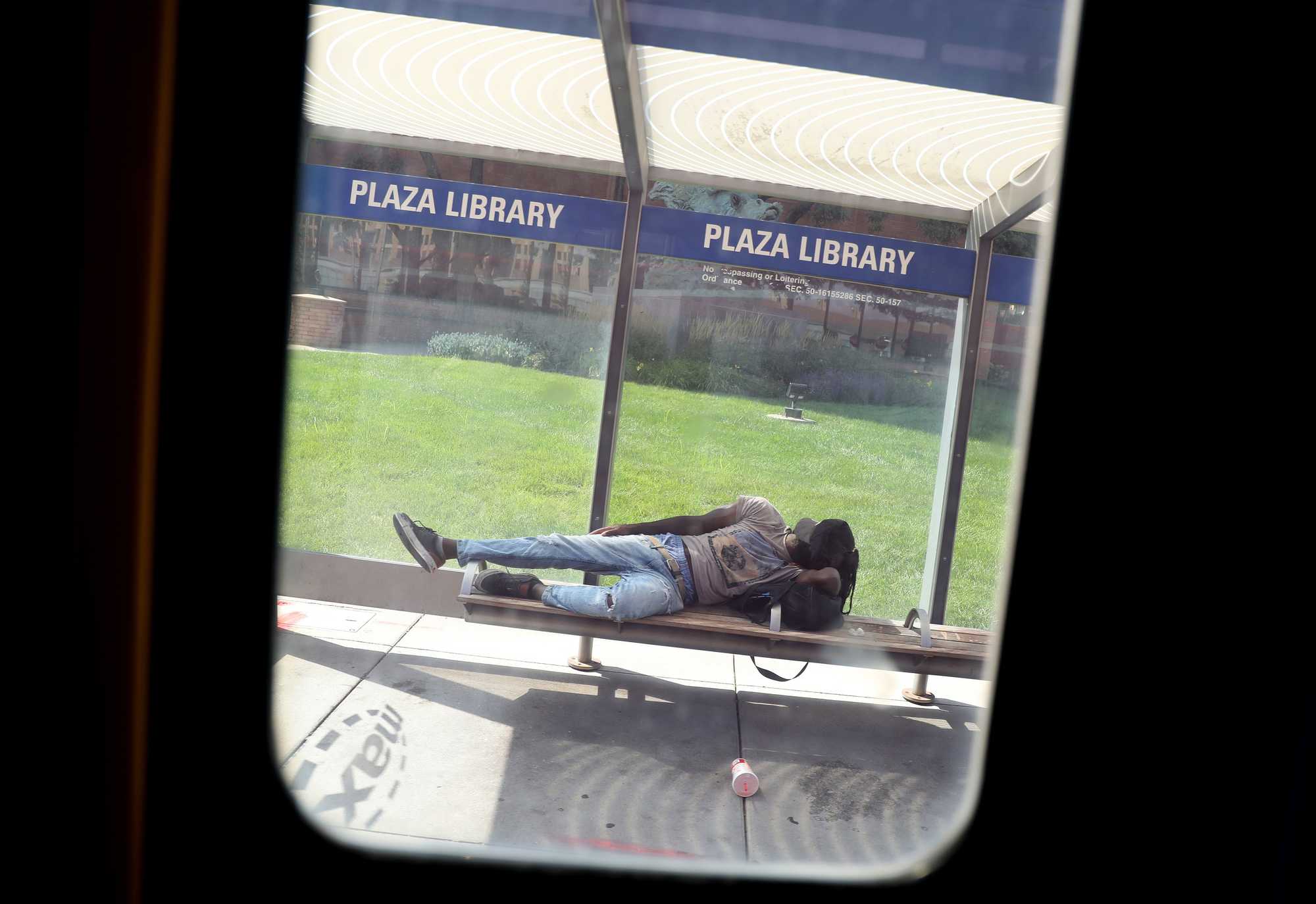

But not everyone is so attached. After letting passengers off at the last stop, driver James Bruce rose from his seat for a two-minute break. He said free fares have made buses more attractive to some riders he has little interest in ferrying — people who, in his view, are there only to cause trouble and take up seats.

Then, Bruce pulled away from the curb in a cloud of diesel exhaust, leaving several passengers waiting for connecting routes. It’s hot on the bench in the sun, and the next bus is already six minutes late.

Join the discussion: Comment on this story.

Credits

- Reporters: Julian Benbow, Diti Kohli, Hanna Krueger, Emma Platoff, Annalisa Quinn, Jenna Russell, Mark Shanahan, Lissandra Villa Huerta

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Pat Greenhouse, Jessica Rinaldi, and Craig F. Walker

- Editor: Francis Storrs

- Managing editor: Stacey Myers

- Photo editors: William Greene and Leanne Burden Seidel

- Video editor: Anush Elbakyan

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: John Hancock

- Copy editors: Carrie Simonelli, Michael Bailey, Marie Piard, and Ashlee Korlach

- Homepage strategy: Leah Becerra

- Audience engagement: Lauren Booker, Heather Ciras, Sadie Layher, Maddie Mortell, and Devin Smith

- Newsletter: LaDonna LaGuerre

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Additional research: Chelsea Henderson and Jeremiah Manion

© 2022 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC