In Harm’s Way

Putting the law on the driver’s side

In Iowa and elsewhere, Republicans push bills granting some legal immunity to motorists who hit protesters.

Switch to light mode

DES MOINES — A large crowd that included fist-raising activists stood on the front steps of Iowa’s five-domed Capitol building in June 2020 and repeatedly chanted “Black lives matter!”

Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds, a Republican, was right there with them.

It was less than three weeks after the police killing of George Floyd and, as in so many other US cities, the streets of Des Moines had been filled with protesters demanding racial justice. But the political reaction in Iowa was unique. The Republican-controlled state legislature quickly drafted and, in one day, unanimously approved a police reform bill called the More Perfect Union Act that banned most chokeholds and took steps to address police misconduct.

In Harm’s Way

Pictured above: Black Liberation Movement member and activist Jaylen Cavil, 24, was struck by an SUV that had the Iowa governor as a passenger in June of 2020. (Scott Morgan for The Boston Globe)

The next afternoon, Reynolds sat at a wooden desk set up under the bright sunshine outside the Capitol and, surrounded by lawmakers from both parties and racial justice activists, she proudly signed the legislation into law.

“The upsetting tragedy, the crime that took George Floyd’s life on a street in Minneapolis, opened the eyes of a nation and sparked a movement,” she said before putting 40 ceremonial pens to paper and handing them to key players in the crowd. “To the thousands of Iowans who have taken to the streets calling for reforms to address inequities faced by people of color in our state, I want you to know that this is not the end of our work. It is just the beginning.”

The moment was a significant olive branch to activists who lay far outside of her political base, and one that sparked some hope for change in Iowa. But the new law wasn’t nearly enough for the activists. They pushed for more reforms. And the backlash to demonstrations that continued around the state and the nation soon set Reynolds on a collision course with the Black Lives Matter movement — and, in a very real sense, one particular protester.

Jaylen Cavil, then 23 years old, and other members of the Des Moines Black Liberation Movement had become something of a shadow to Reynolds after she signed the More Perfect Union Act. They showed up every day outside her office to pressure her to restore voting rights to ex-felons, chanting, “Hey Kim! Use your pen! Sign that s***! Use your pen. Sign that s***! 60,000! 60,000! Need to vote!”

On June 30, 2020, they took that campaign on the road, about two dozen of them trailing Reynolds along highways hugged tightly by cornfields as she headed to events 90 miles northeast of Des Moines. Under the gaze of a 15-foot tall longhorn bull at the entrance to the small rural community of Ackley, they gathered with their cow bells and megaphones at the edge of a two-lane road outside Family Traditions Meat Co. while she toured the small business and picked up a “brisket bomb” sandwich for lunch.

The increasingly volatile combination of protesters and vehicles was in place. All it needed was a spark.

When Reynolds climbed into the backseat of her state-issued Chevrolet Suburban, Cavil positioned himself where the gravel parking lot met the road, a megaphone in his right hand and a water bottle in his left.

“I’m going to stand here and the car’s going to stop and we’re all going to yell and make Kim Reynolds hear us and maybe she’ll roll down her window,” Cavil, now 24, recalled thinking at the time.

But the SUV didn’t stop.

Video showed the slow-moving vehicle striking Cavil as he walked in front of it. Cavil turned in place at the last second and the right front of the SUV bumped his hip. He slid across the front of the vehicle before pivoting and moving away as state police jumped in and the vehicle stopped. He was uninjured but infuriated.

“He could have stopped. He could have turned,” Cavil said recently of the driver. “He just kept going straight.”

An Iowa State Patrol spokesman said Cavil intentionally stepped in front of the SUV, which was trying to turn away from him. Reynolds said her driver “acted appropriately.”

Nearly a year later — in a state that had at least four other incidents in 2020 involving motorists driving into groups of racial injustice protesters — Reynolds once again signed a law prompted by Floyd’s killing. But this one veered in the opposite direction from the reforms activists had cheered on the capitol steps.

Her Back the Blue Act mostly focused on pro-law enforcement measures. It increased criminal penalties for protest-related crimes. And when it came to vehicles striking protesters, the law took the side of the drivers.

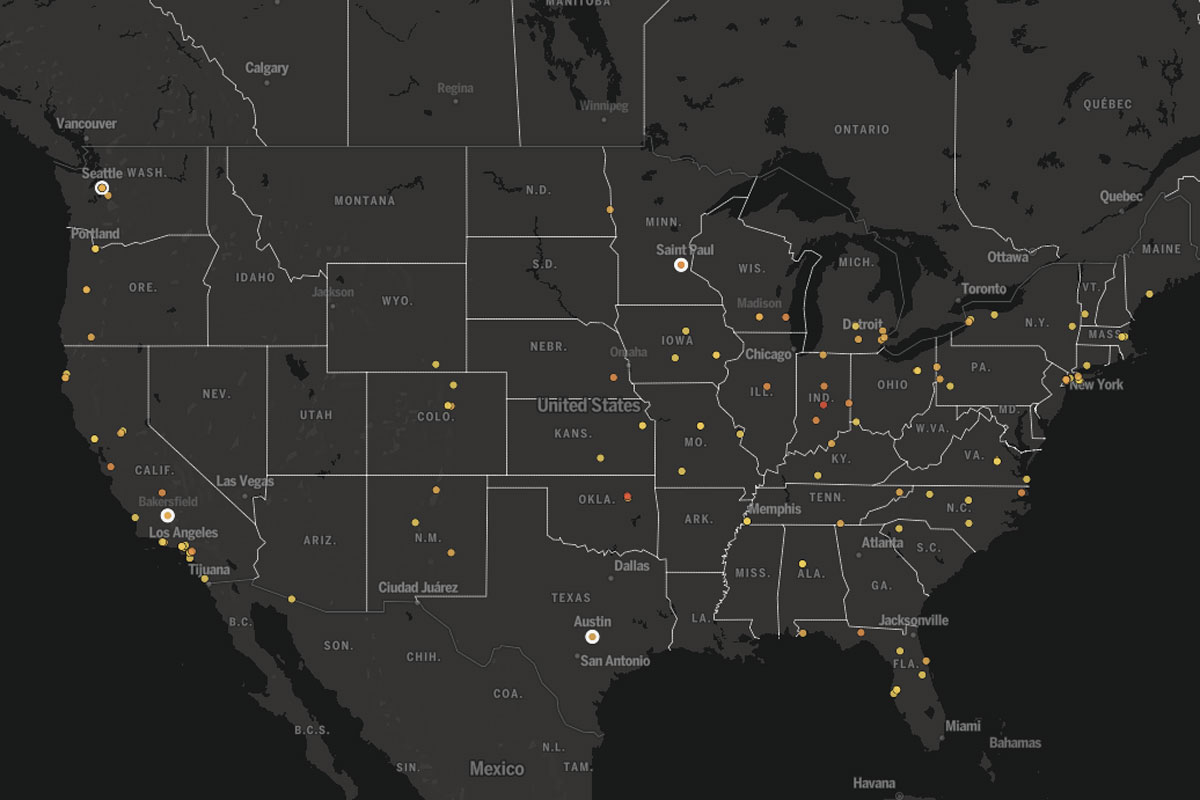

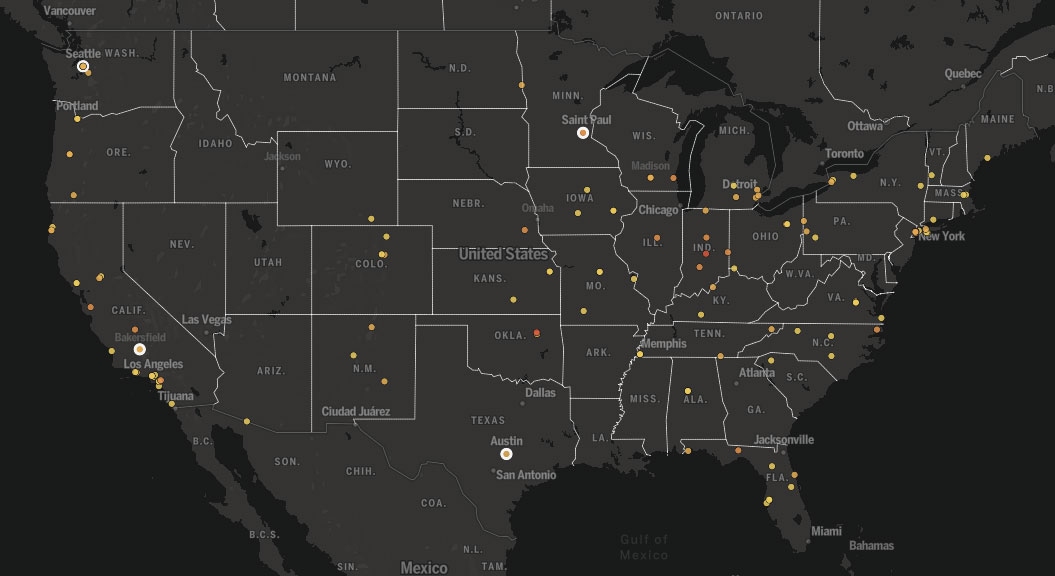

Iowa is one of three states, along with Oklahoma and Florida, to enact laws this year giving drivers some degree of legal immunity if they use their vehicles to hurt protesters, part of a wave of “hit and kill” bills introduced in 13 other states by Republican legislators since 2017. Most of those proposals came after one of the most sustained periods of demonstrations in US history following Floyd’s murder, and the effort to crack down on protesters has sent a chilling message to activists, who believe it will encourage violence against them.

Driver immunity laws across the country

Three states have enacted laws that give drivers some level of immunity from charges after hitting protesters with a vehicle. Similar bills have been introduced in 13 other states since 2017. Click on individual states below to see more information on the state’s legislation.

- No legislation

- Enacted

- Pending

- Expired or defeated

Republicans’ rationale for backing the bills — that it is people behind the wheel of a vehicle weighing thousands of pounds, not pedestrians, who are scared and at risk during protests that have been overwhelmingly peaceful — also reveals the extreme lens with which many conservatives see Black Lives Matter and other protesters, and the legitimacy of their dissent.

As long as they exercise “due care” and are not acting with “reckless or willful misconduct,” drivers now are granted immunity from lawsuits in Iowa if they injure anyone with their vehicle “who is participating in a protest, demonstration, riot, or unlawful assembly or who is engaging in disorderly conduct and is blocking traffic in a public street or highway.” The immunity does not apply to protests that have valid permits to be on the streets, but most protests, which are spontaneous or sometimes deliberately disruptive to call attention to a cause, do not have those permits.

The new laws and proposals came after a sharp rise in people driving their vehicles into protests. A Globe analysis found 139 instances of what researchers call vehicle rammings between Floyd’s death on May 25, 2020, and Sept. 30, 2021, that caused 100 injuries and killed at least three people. Drivers had a range of motivations, including racial hatred of protesters, anger about traffic backups, or fears of being stuck in a crowd. The Globe confirmed the existence of charges in less than half the incidents, and many were simply misdemeanors or traffic citations.

In Iowa, civil rights advocates are still reeling from how quickly the state’s Republicans boomeranged from embracing calls for police reform to protecting people who harm the protesters pushing for those changes.

Reynolds, who was convicted in two drunken driving incidents 20 years ago before quitting drinking, had lent a particularly sympathetic ear to some of their demands for change. And she ultimately signed an executive order in August 2020 restoring voting rights for felons who have served their sentences. Her spokesman did not respond to Globe requests for an interview with the governor.

Some experts fear the driver immunity provision in the new law may be the permission some angry Iowans are seeking to transform their hostility to Black Lives Matter and other liberal protesters into violence.

“There’s this kind of vigilantism that’s returning,” said Nick Robinson, a senior legal adviser at the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, which has tracked a sharp increase in legislative proposals nationwide to restrict the right to peacefully protest. “If we deem these protesters to be rioters, we’re going to take the law into our own hands. And if that means injuring them with our vehicle or killing them with our vehicle, we have an expectation that the state will protect us. That’s just a recipe for disaster.”

Marching on roads and highways is a longstanding tactic of protesters to draw attention to their cause, snarling traffic and blocking intersections in acts of civil disobedience.

“Get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes, until the revolution of 1776 is complete,” civil rights icon John Lewis told the crowd at the March on Washington in 1963. Two years later, a phalanx of police officers wielding clubs and firing tear gas viciously attacked Lewis and 600 other demonstrators as they peacefully marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., in an iconic moment of the civil rights movement.

“We know it’s not lawful to block cars in the street,” Cavil said. “That’s what civil disobedience is. It’s purposefully disobeying the law in a nonviolent way.”

But when present-day racial injustice protesters deployed the tactic after the police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014 and other people of color around the country, it quickly sparked a backlash that only intensified following the election of Donald Trump as president.

Republican state legislators sought to toughen penalties for blocking roadways as right wing memes joking about intentionally running over liberal protesters proliferated online. Then, a new, more radical idea surfaced: grant drivers immunity if they unintentionally hit a protester.

A nationwide threat

Drivers have steered their vehicles toward protesters at least 139 times across the United States between George Floyd’s murder May 25, 2020 and Sept. 30, 2021. These rammings occurred in big cities and small, from Los Angeles to Brookwood, Ala. And in 38 percent of those incidents, the Globe found no evidence drivers faced charges.

“It’s shifting the burden of proof from the motor vehicle driver to the pedestrian,” North Dakota state Representative Keith Kempenich declared when he introduced a driver immunity bill in early 2017 in response to protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline, an underground oil pipeline through sensitive environmental and cultural areas. He told reporters he was motivated to take action after he claimed that protesters on a highway swarmed around the car of his 72-year-old mother-in-law.

Over the next several months, Republicans introduced driver immunity bills in Tennessee, Florida, North Carolina, Texas, and Rhode Island. Lobbyists and analysts said there was no indication of a coordinated nationwide effort to push the measures then or now. The language of the bills varied and many were triggered by local events. In Tennessee, for example, a bill followed protests in Nashville over Trump’s ban on travelers from several Muslim-majority countries.

“We don’t want anyone to be hurt, but people should not knowingly put themselves in harm’s way when you’ve got moms and dads trying to get their kids to school,” said Tennessee state Representative Matthew Hill, one of the bill’s sponsors.

The proposals were viewed as extreme and none of them was approved, although the North Carolina bill passed the state General Assembly. The effort swiftly lost momentum after Heather Heyer, 32, was killed in August 2017, when James Fields Jr. intentionally drove his car into people counter-protesting the “Unite the Right” white supremacist gathering in Charlottesville, Va.

Driver immunity was largely dormant as an issue until the fall of 2020. Then, in the aftermath of a summer of nationwide racial injustice protests, Republicans in 11 states began to unleash a second, larger flurry of “hit and kill” bills. They came amid a more expansive effort by Republicans to crack down on protesters in the lead-up to and immediate aftermath of a contentious presidential election.

“Recently in our country, we have seen attacks on law enforcement. We’ve seen disorder and tumult in many cities across the country,” Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, a Republican, said in September 2020 as he stood with a dozen sheriffs and other law enforcement officials to unveil the Combatting Violence, Disorder and Looting and Law Enforcement Protection Act. “I think that this has been a really sad chapter in American history.”

Although he acknowledged Florida had not experienced much violence, his sweeping proposal included elevating to felonies crimes committed during a riot, which is broadly defined, requiring arrested protesters to be held until they make a court appearance —and specifying that a “driver is NOT liable for injury or death caused if fleeing for safety from a mob.” The Republican-controlled legislature voted largely along party lines to approve a bill similar to his proposal and DeSantis signed it in April.

The driver immunity provision, which shields motorists from civil lawsuits for any injury or death caused by a collision, scares activists like Francesca Menes, chair of the Black Collective, a Miami group working to increase political consciousness and economic power of Black communities. A federal judge in September blocked the state from enforcing the law after a suit filed by the Black Collective and other civil rights groups. DeSantis said he will appeal.

“It’s going to encourage people to want to hit people,” Menes said of the driver immunity provision. “People are going to be in their big trucks with their big Confederate flags to make it very visible to us … that they are willing to run us over and we cannot sue them for damages should they hurt us and we have to recover our medical costs.”

In Oklahoma, a law also signed in April, went where Florida’s did not: prohibiting not just lawsuits but criminal charges for drivers under certain circumstances. The bill stemmed from a May 2020 incident during a Tulsa Black Lives Matter protest in which a pickup truck pulling a horse trailer drove through a crowd on a highway.

Three people were seriously injured, including Ryan Knight, a father of five who was paralyzed from the chest down after he fell from an overpass as the truck pushed into the panicked crowd. The district attorney decided not to file charges against the driver, saying he and his wife and two children traveling with them were victims of a “violent and unprovoked attack.”

But Republican lawmakers pushed through a bill anyway, signed into law by GOP Governor Kevin Stitt, that adds new penalties for protest-related crimes and grants drivers immunity for any injuries that occur when “fleeing from a riot” while fearing for their own serious injury or death as long as they exercise “due care.” A federal judge last week temporarily blocked part of the law, but left the driver immunity provision in place.

“I certainly support the right to peacefully protest and assemble,” Oklahoma state Representative Kevin West, one of the bill’s sponsors, said in a statement when the law was signed. “I will not, however, endorse rioters that spill onto city or state streets, blocking traffic and even harming property of vehicle operators who are simply trying to move freely. This law gives clarity to those motorists that they are in fact within their rights to seek safety.”

This same logic had taken hold several hundred miles north in Iowa.

During the summer of 2020, racial justice demonstrations didn’t just happen in Des Moines. People took to the streets in other communities, large and small, across the state and the protests began to meet conservative resistance.

“It might have been easy at first for some of these rural legislators to dismiss this as just a Des Moines thing,” said Adam Mason, a longtime lobbyist with Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement, a public interest group. “But then you see it happening in your rural communities as well and they start to get nervous.”

Although the Iowa protests were overwhelmingly peaceful, Tim Hagle, an associate political science professor at the University of Iowa, said incidents of violence at protests around the country helped to alter the political dynamic in Iowa.

Democrats had hoped for big gains in the state legislature in last November’s elections. But Republicans picked up seats and Trump again comfortably won the state’s six electoral votes. When the more conservative legislature convened last winter, Reynolds’s position on police reform had shifted. Although she said in her annual address that she was readying proposed legislation that “continues our march toward racial justice,” Reynolds also joined the Republican chorus led by Trump against calls to defund the police and vowed she “will always have their back.”

Newsletter sign-up: The Globe Investigates

Spotlight reports and special projects that hold the powerful accountable and uncover waste, fraud, and abuse.

Reynolds’s initial Back the Blue Act proposal banned racial profiling by police but was centered on pro-law enforcement measures, including denying state money to localities that decreased police budgets and increasing penalties for protest-related crimes.

As the bill advanced through the legislature this year, it became a vehicle for Republicans to push back on Black Lives Matter protesters, who were being portrayed as criminal cop-haters in conservative media. GOP lawmakers removed the racial profiling ban. They also added the driver immunity provision from a bill by Republican state Senator Julian Garrett of Indianola, a suburb of Des Moines.

“We’ve got to stop this law-violating,” Garrett told his colleagues as they debated the Back the Blue Act in May. “We’ve got to stop this criminal activity if we possibly can.”

Garrett said in an interview that he pushed for driver immunity after protesters shut down streets and blocked Interstate 80 in the past. He said he didn’t think a driver should be liable if “you accidentally run into somebody ... who was out violating the law.”

As for concerns the immunity would endanger protesters and make them afraid to march in the streets, Garrett said, “If you don’t violate the law, you’ve got nothing to worry about.”

Democrats including Representative Ross Wilburn of Ames, a member of the legislature’s Black caucus, were appalled by the bill and stunned by the driver immunity provision.

“It flies in the face of civil rights protests in the ‘60s and the march for justice that has continued ever since then,” said Wilburn, who also is the state Democratic Party chairman. “It was an extreme overreaction to people and their peaceful protests.”

The law felt like a slap in the face to activists such as Ala Mohamed, 22, co-founder of the Iowa Freedom Riders, who experienced vehicle violence first-hand during the Floyd demonstrations.

She was protesting with about 200 people at an Iowa City intersection on Aug. 21, 2020, when a Toyota Camry sped into the crowd. The vehicle hit several people, although nobody was seriously injured. Police arrested the driver Michael Ray Stepanek, 45, of Iowa City, who told them the protesters needed “an attitude adjustment.” He later agreed to a plea deal that allows a felony charge of willful injury resulting in bodily injury to be dismissed if he completes a three-year probation.

Caitlin Healy/Globe Staff

In their words

Ala Mohamed

Iowa City, Iowa

Ala Mohamed is a student at the University of Iowa and co-founder of the Iowa Freedom Riders, a racial justice and liberation group. She organized and participated in a George Floyd protest in August 2020 and witnessed two incidents of vehicles hitting protesters.

Minutes before that incident, Mohamed said, a car shot through the same intersection as she and volunteers prepared to block traffic for the approaching protest. One of the volunteers grabbed onto the car’s hood for a short stretch before rolling off, shaken but unharmed, Mohamed said. A week later in Iowa City, witness video showed a car backing into several protesters, with a passenger yelling “white power” and throwing a water bottle at them.

“It’s going to affect a lot of Black and brown people because we are the ones who are protesting,” Mohamed, now a senior at the University of Iowa, said of the state’s new driver immunity law. “It just goes to show we have a long way to go.”

The day Iowa’s Back the Blue Act passed this spring, Cavil, the activist who was hit by Reynolds’s car, said he got Twitter replies and messages with images of cars running people over.

“Someone kept doing the same ‘Grand Theft Auto’ gif of someone getting flattened by a car, saying, ‘I can’t wait for your next protest,’” Cavil said. “I think it emboldens people.”

Reynolds’s swing between supporting modest criminal justice reforms and the Back the Blue Act mirrors a larger national realignment on the right in reaction to widespread protests following police shootings of unarmed people of color. Many Republican-controlled state legislatures began leading the way on criminal justice reforms in recent years, driven in part by a desire to cut the costs of ballooning prison populations. But Trump made opposing Black Lives Matter a key part of his presidential campaign, calling the slogan a “symbol of hate” and warning protesters, “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.”

Iowa civil rights advocates said national politics and a backlash to the Floyd protests played a role in Iowa’s shift from police reform to a crackdown on protesters.

“This is so unrelated to any fact on the ground in Iowa, and it’s coupled with a national thrust among elected officials to restrict people’s rights to protest,” said Pete McRoberts, policy director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Iowa. “It’s not like there was some enormous societal problem and that the governor just had to get involved to fix it.”

Reynolds, a former county treasurer and state senator, was lieutenant governor and took office in 2017 when then-Governor Terry Branstad became ambassador to China, then won a full term in 2018. She faces reelection in 2022 and may have her sights set higher. She campaigned with Trump last fall and has publicly clashed with President Biden over the state’s ban on mask mandates. Bob Vander Plaats, head of the Iowa-based conservative Christian group The Family Leader, suggested this summer that Reynolds would be a strong running mate for Trump or whoever wins the party’s 2024 presidential nomination.

When Reynolds signed the Back the Blue Act into law in June, there were no racial justice activists behind her chanting “Black lives matter!” This time, in a ceremony at the Iowa Law Enforcement Academy, she was surrounded by police officers.

Credits

- Reporter: Jim Puzzanghera

- Editors: Elizabeth Goodwin, Jim Puzzanghera, and Mark Morrow

- Photographer: Scott Morgan

- Photo editor: Kim Chapin

- Director of photography: William Greene

- Video production: Caitlin Healy

- Copy editors: Michael Bailey and Mary Creane

- Digital storytelling, design, and development: John Hancock

- Audience experience and engagement: Christina Prignano

- Quality assurance: Chelsey Johnson and Jackson Pace

© Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC