In Harm’s Way

A grisly blueprint of terror

Charlottesville car attack four years ago foreshadowed a summer of violence in 2020

Switch to light mode

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va. — The violent clashes between white supremacists and racial justice protesters had not yet swept through this old college town when, in May 2017, James Alex Fields Jr. sent a bit of twisted humor to his friend on Instagram.

It was a photograph of a dark gray Dodge Challenger ramming into a group of cyclists, their bikes and bodies tossed into the air. “PROTEST,” read a white block of text, “BUT I’M LATE FOR WORK!!”

In Harm’s Way

Pictured above: People flew into the air as a vehicle was driven into a group of protesters demonstrating against a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Va. (Ryan M. Kelly/The Daily Progress via AP/file)

“When I see protesters blocking,” Fields, then 20, added, tapping his grisly threat onto his iPhone from somewhere in the small town of Maumee, Ohio, where he lived just southwest of Toledo.

Three months later, on a cool night in August, Fields climbed into his own Dodge Challenger and drove the nine hours to Charlottesville. He arrived before dawn and hung around the empty city before eventually making his way to a downtown park, where he joined the white supremacists, Neo-Nazis, Klansmen, and members of other far right-wing groups rallying to consolidate the US white power movement and denounce the planned removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

Hundreds of counter-protesters responded with their own show of solidarity, leading to skirmishes and chaos that morning. But by the early afternoon, police officers had broken up the event, and people waving Black Lives Matter signs and LGBTQ flags streamed into the bright, summer light, feeling victorious. As they rounded Fourth Street, marching past old, brick buildings to a pedestrian mall lined with cafes and restaurants, they chanted, “Whose streets? Our streets!”

Farther up the hill, Fields waited. He watched for about a minute before he slowly backed up, shifted his car into gear, and barreled straight into the crowd, his tires screeching against the pavement.

A nationwide threat

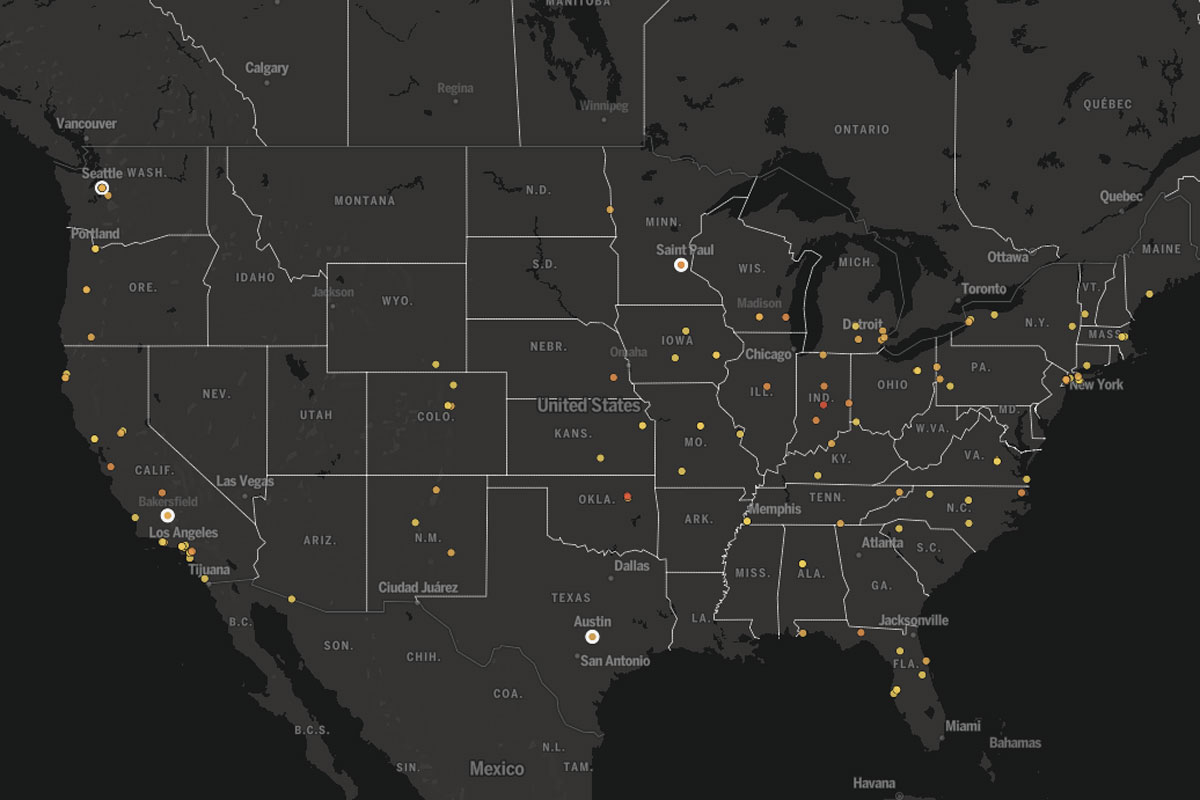

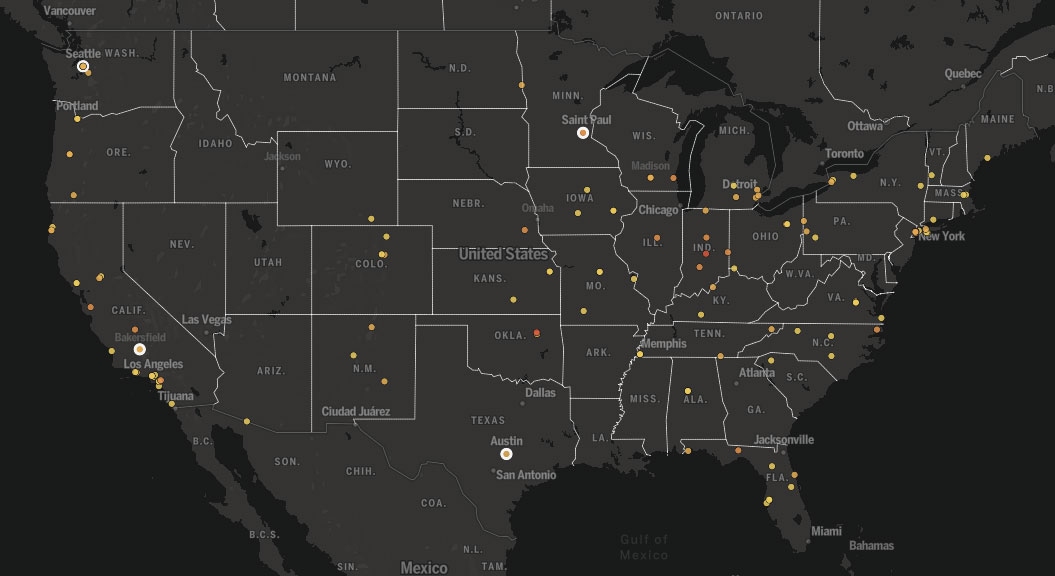

Drivers have steered their vehicles toward protesters at least 139 times across the United States between George Floyd’s murder May 25, 2020 and Sept. 30, 2021. These rammings occurred in big cities and small, from Los Angeles to Brookwood, Ala.. And in 38 percent of those incidents, the Globe found no evidence drivers faced charges.

Marcus Martin looked up from his cellphone just in time to push his fiancée, Marissa, out of the way before he was flung upward. Alexis Morris was struck so suddenly by the car, and with such force, that she thought a bomb had exploded. She was knocked to the ground, with a badly broken leg.

Brian Henderson threw himself over the car’s hood and avoided the brunt of the impact. But, unaware, Heather Heyer, 32, stood directly in the Challenger’s path and was hit with its entire two-ton weight. As Heyer’s body was thrust into the air, Jeanne Peterson, whose right leg was crushed under the car, said she locked eyes with hers. They were lifeless, she recalled later.

People heard the sickening thud of bodies, then a boom as Fields slammed into a white Camry and the Camry plowed into a maroon minivan.

From a distance, Ryan Kelly, a news photographer for The Daily Progress, had seen Fields reverse and reflexively pointed his lens at the dark gray Challenger as he heard the squeal of tires. He snapped a string of photos of the crash, including one image that would win a Pulitzer Prize. It bore an eerie resemblance to the grim, captioned image that Fields had sent his friend — the Internet meme.

Many hoped that the extreme cruelty and cowardice of the car attack in Charlottesville would make it the last of its kind. The horror of the murderous white supremacist assault echoed loudly in a city that had long been grappling with its Confederate symbols and vestiges of slavery, from Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello to the University of Virginia’s bucolic campus — founded by slave holders with wealth earned from slavery — to the equestrian bronze of General Lee, long a fixture in the city’s historic district.

Plastic flowers and stuffed animals were mounded on the street in Heyer’s memory. Photos of her hung inside downtown shop windows. People plastered “Heather” and “C’ville” bumper-stickers to their cars, and here, as across the country, there seemed to be a reawakening to the growing threat of white supremacist extremism and the deadly violence that racist and divisive political rhetoric, which reverberated from President Trump’s rally speeches to far-right corners of the Internet, could inspire among its followers.

Yet, as the racial justice demonstrations continued, ramping up in the summer of 2020 after the murder of George Floyd, vehicle violence against protesters became a frightening and near-daily fact of life. A Globe analysis has found that at least 139 people have, since Fields’s deadly act, driven their vehicles into demonstrations, causing 100 injuries, three deaths, and spurring a fatal shooting. While some rammings may have been unintentional, at least nine of them meet the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ definition of domestic terrorism — deliberate violence by everyday people to achieve political goals — making the vehicular assault in Charlottesville a foundational emblem for a rising form of violence on American streets. That attack was the beginning of something sinister, not the end.

The Globe series, which began Sunday, aims to comprehensively document this unthinkable pattern — violence some states have all but sanctioned, aimed at constitutionally protected gatherings — which has to date drawn comparatively little national notice and response. A collision of rights and wrongs is underway, and rights are far too often on the losing end.

The Globe was able to confirm charges in only 65 incidents, and some drivers were never identified or arrested by police. Those who were caught or later charged often said they were frightened of the protesters, and prosecutors tended not to explore their motives or whether the driver felt racial or ideological hate toward the demonstrators. The Charlottesville terror attack is thus a rare case that provides a deeper look into the mindset of one attacker — and the broader online campaign on the right that has helped dehumanize protesters and normalize the violence, in part by glorifying Fields and spreading memes like the one he shared with his friend.

This retelling of the case is based on interviews with Fields’s living victims and with more than two dozen counterterrorism and disinformation analysts, law enforcement officers, and national security officials, and on a review of hundreds of criminal and civil court records, including a lawsuit filed on behalf of victims that has shed new light on the extent of the online coordination ahead of the attack.

In the months leading up to the deadly rally, talk of transforming one’s vehicle into a weapon saturated far-right social media spaces and conversations on Discord, a chat platform for gamers, according to the civil case that cites tens of thousands of messages from that platform and others exchanged among the rally’s organizers and participants.

White supremacists including Richard Spencer, a defendant in the case, and Jason Kessler, of Charlottesville, circulated memes and texts extolling Hitler and his Jewish genocide and others that portrayed Jews and Black people as enemies of white people. Other users encouraged mowing down antiracism protesters, with some framing the attacks as self-defense, and one sharing a meme featuring a John Deere tractor, calling it a “multi-lane protester digestor.”

“Is it legal to run over protestors blocking roadways? I’m NOT just [expletive]. I would like clarification,” that same user wrote in another post.

The online coordination and threats of violence did not appear to draw much interest from federal law enforcement officials at the time; they were serving a president determined to downplay the homegrown threat of white supremacy and were part of a national security bureaucracy that had long prioritized investigating terrorists inspired by radical Islam over any other kind of extremism. It’s a blind spot that has benefited drivers, most of whom are white, who have followed in Fields’s tracks in the years since.

“There has been so little scrutiny and accountability when it comes to these cases that so often we chalk them up to isolated incidents and refuse to see the pattern,” said Amy Spitalnick, executive director of Integrity First for America, a nonprofit funding the case against Spencer and other rally organizers. “These attacks aren’t accidents. They’re intended to instill terror in people and communities.”

Caitlin Healy/Globe Staff

In their words

Constance Paige Young

Charlottesville, Virginia

Constance Paige Young was injured when a car drove into a group of counter-protesters at a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017. She is an antiracism activist and advocates for survivors of sexual violence.

Since the earliest days of the Internet, memes like the ones Fields shared have been its so-called second-language, flippant mashups of pictures and text that allow groups to fluidly transfer ideas, trade jokes, and engage in other kinds of communication. Memes are commonplace, and usually harmless even if offensive. But in the hands of extremists, they can become powerful tools to indoctrinate people into dangerous ideologies and incite so-called “lone wolves,” like Fields, to commit isolated acts of terror. The incidents, that is, appear random but often are not.

In the United States, federal law enforcement and counterterrorism officers started investigating the role that memes and other online content play in this so-called “stochastic” — random-seeming — terrorism, as they tracked Al Qaeda, the first terrorist organization to wield the Internet as a tool to manipulate the masses and spread online manuals on how to build bombs and launch attacks. As early as 2010, an Al Qaeda webzine titled “The Ultimate Mowing Machine” summoned followers to utilize a pickup truck as a “mowing machine, not to mow grass but mow down the enemies of Allah.”

Four years later, its deadly offshoot, the Islamic State, or ISIS, rose to power, in part by flooding the web with social media campaigns and gory videos of beheadings that shocked the world. Its spokesman, Abu Mohammad al-Adnani, infamously called for lone wolf attacks on any single “disbelieving American, Frenchman or any of their allies” using whatever weapon available, whether it be a rock, a knife, or “your car.”

“There has been so little scrutiny and accountability when it comes to these cases that so often we chalk them up to isolated incidents and refuse to see the pattern. These attacks aren’t accidents. They’re intended to instill terror in people and communities.”

— Amy Spitalnick, Executive director of Integrity First for America

The foreign terror organizations’ ideology differs markedly from that of the US white power movement: ISIS members have sought to create a caliphate, or autonomous region under an Islamic ruler in the heart of the Middle East, while American white supremacist extremists seek to build an all-white ethnostate, reaching far beyond the nation’s borders.

But the tactics they use to recruit, radicalize, and push the most unstable of followers to act on violent notions are similar, counterterrorism and national security experts said. Through online channels, Islamic and white supremacist extremists alike seek out those feeling disconnected from society and try to propagate and perpetuate the feeling that their way of life is under threat, that the political system to address their grievances is broken, and that the only way to address the moral and societal wrongs that outrage them is by inflicting terror.

In the case of ISIS fighters, the enemies in memes are thus “infidels” and Western-backed autocracies. Among white supremacists and members of the white power movement, the targets are immigrants, people of color, Jews, and anyone else who they fear threatens to outnumber and replace whites, not only in the United States but also around the world.

Memes live and die by social media algorithms that decide their reach: The more people like or engage with a certain kind of meme, the more they are fed similar kinds of memes by social media platforms. And their effectiveness relies on mixing humor with edginess, earnestness with plausible deniability, making it difficult to draw a causal connection between the savage edge of a meme and the savagery that may follow.

Nikolas Guggenberger, executive director of the Yale Information Society Project, a center for scholars studying law, technology, and society, sees such memes as “a small piece of a much larger puzzle” of the process of radicalization. Frequent interactions with a certain kind of meme “might bring someone closer to the edge, or for someone who is already close to the edge, it might just push them over,” Guggenberger said.

However an extremist comes to embrace violence, a common thread is that the lives of their targets have been thoroughly devalued in their minds, said Talia Lavin, whose research infiltrating white power groups became the basis of her book, “Culture Warlords: My Journey Into the Dark Web of White Supremacy.”

“That is the essential act that is being done here, which is reducing the worth of human lives into a punchline,” she said.

As Fields plowed into the Camry, which had stopped in traffic amid the impromptu march, people screamed and rushed in all directions. A woman held her arms out amid the chaos to protect her friends. Fields revved his car and fled before anyone had a chance to recover from the shock. He kept going, trailed by a sheriff’s deputy blaring his sirens, until he eventually pulled over. When officers found him in his car, his glasses had been knocked to the ground and his iPhone was still plugged into the console with directions for his route home. His shirt was stained from the earlier scuffles between demonstrators at the park.

In his conversations with police later, he said he was sorry and had not meant to hurt anyone, then cried and hyperventilated upon learning he had killed a woman. “I thought they were attacking me,” he said in body camera footage.

In this also, his assault was an eerie preface to the car rammings to come: Drivers who have run down demonstrators often say they acted in fear — and law enforcement has been, in many cases, sympathetic to that claim.

At his trial in late 2018, Fields’s defense lawyers pointed to that final tearful scene as they sought to paint a picture of a young, troubled man who had taken a day off from his job as a security officer to attend the rally and had every intention of behaving peaceably and then going home. He didn’t bring any weapons or protective gear, they said, no guns or shield, although Fields does appear in a photo from that day holding a black shield. The car attack memes he posted were not unlike other signs at the rally, they argued. They pointed to one counter-demonstrator who toted a gun and held a placard that read, “This machine kills fascists.”

Plus, defense attorney Denise Lunsford added, many others had posted that kind of content — not just Fields.

Prosecutors Joe Platania and Nina-Alice Antony countered that Fields indeed had a weapon, his car, calling the car attack memes he posted a “blueprint for the crime.” He might not have spent three months planning the attack, Platania told jurors, but in the moment he put the car into gear and slammed into the crowd he “seized the opportunity to make the meme a reality.”

“What those posts really give you is a glimpse into his mind,” he said. “It gives you a glimpse into the attitude of those people who would be out on the street protesting.”

Initially, Judge Richard Moore had not been inclined to admit the posted memes as evidence out of concern that they could unfairly prejudice the jury against Fields. But reading them over at home on his recliner one night as the trial commenced, he could not ignore the similarities between the images and the scene of the crime, he told the lawyers in court.

“It’s a car running into protesters, and that’s the thing I could not get away from,” the judge said. “One would not know whether he’s trying to re-create that or whether it just says something about his intent or his view of people, but either way it would be relevant if it shows it wasn’t an accident, if it shows he thought poorly of protesters.”

Moore’s concern about Fields’s motive was compounded by other facts. Days before the crash, Fields had received a text from his mother warning him to be careful at the rally. Fields replied with a photo of Hitler. “We’re not the ones who need to be careful,” he fired back. On jail calls with her after his arrest, he called the mother of Heather Heyer, the woman he killed, a “communist” and one of those “antiwhite supremacists.”

“She is the enemy,” Fields said.

After a seven-hour deliberation, a jury found Fields guilty of first-degree murder, along with other felony counts for injuring 35 people with his car. He received a second life sentence after he pleaded guilty to 29 federal hate crimes. But it is the civil case against Spencer and other “Unite the Right” rally defendants, which opened with jury selection last week, not Fields’s criminal cases, that is expected to give the clearest glimpse into his online world.

The foundation of the meme shared by Fields is a photograph of a drunk driver hitting a group of cyclists competing in a 2008 race in Mexico. Its style recalls memes propagated by gamers and others in the earliest days of the Internet that made fun of gruesome car crashes and shocking acts of violence but were divorced from any political context, according to Brian Friedberg, who studies far right-wing platforms at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center and analyzed it for the Globe.

Such memes took on a new life sometime around 2014, as Black Lives Matter protests began to gain national momentum after the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. The new constructions joked about hurting or driving over protesters and have tended to crop up in cycles ever since, ebbing and flowing with the energy of the movement to end police brutality against unarmed Black people.

One of the most popular — later re-created on T-shirts and bumper-stickers — was a crudely drawn image of a Humvee hitting stick people, the words “All Lives Splatter” scrawled across the top.

Others referred to demonstrators as mere speed bumps.

The car attack memes proliferated among a cross-section of right-wing sites and users, including the Facebook pages of some law enforcement, conservative, and pro-confederacy groups. And though they did not necessarily originate in white supremacists’ spaces, they festered there, researchers and counterterrorism experts said.

Online echo chambers have furthered the reach of an American white power movement that since the 1980s has become increasingly dangerous. The movement has decentralized into cells to avoid the snare of law enforcement and become adept at flouting criminal laws while, like the memes themselves, still maintaining plausible deniability about its violent intentions, domestic terrorism experts said. And unlike the violent online content produced by ISIS, which has often been the subject of intense FBI scrutiny, the posts dehumanizing liberal protesters have been allowed to filter into the mainstream.

Just who created the car attack meme shared by Fields is unknown. But the captioned image appeared on the Internet for the first time on Twitter on Jan. 20, 2017, posted by a user who has since been kicked off the platform, as protests organized by Democrats and women’s groups against Trump’s presidency heated up on the day of his inauguration, activating a backlash on the right.

When Fields first shared it on May 12, 2017, he had been locked in a private Instagram conversation about politics with a friend. He sent the image along with World War II photos of Hitler and Jewish people, according to the investigators who extracted the content from his phone. Four days later, he published a similar version of the car attack meme on Instagram in a public post without comment. Fields, who had called for violence in the name of white supremacy since high school, also went on to publish posts in support of Hitler and denying the Holocaust, and often referred to Black people by racial slurs, according to his federal sentencing memos.

He was a threat in plain sight, but no one appeared to be watching.

The campaign in Charlottesville to stop the removal of the Robert E. Lee statue would draw national attention in August, when one night before Fields plowed his car into counter-protesters, hundreds of white people, clad in white polo shirts and carrying tiki torches, evoking the KKK, marched on the University of Virginia, chanting, “You will not replace us.”

But at an earlier, much less populated gathering in May, one day after Fields sent the car attack meme to his friend, Richard Spencer led a similar procession at his alma mater, the University of Virginia. He banged a drum before Confederate flag-waving followers and quoted the kind of meme flourishing in the far right online spaces that drew young, disgruntled white men like Fields. “I was born too late for the Crusades,” Spencer said. “I was born too early for the conquest of Mars, but I was born at the right time for the race war.”

Homegrown extremism fueled by hate and racism had long benefited from federal inattention, yet it intensified to new levels as domestic terrorism investigations withered during the Trump years, experts said. In October 2018, a white nationalist shouting anti-Semitic slurs and armed with an AR-15 semi-automatic rifle and handguns killed 11 people at a synagogue in Pittsburgh. In August 2019, a self-proclaimed white supremacist drove to El Paso to “kill Mexicans” at a Walmart, leaving 23 people dead.

There was a foiled plot by far right, antigovernment extremists, the boogaloo boys, to kidnap the Democratic governor of Michigan, Gretchen Whitmer. And on Jan. 6, 2021, many from the same far right militias and groups that rallied in Charlottesville stormed the US Capitol, some of them carrying Confederate flags and wearing Nazi insignia.

And, in the months that followed Floyd’s murder, car ramming incidents proliferated.

Newsletter sign-up: The Globe Investigates

Spotlight reports and special projects that hold the powerful accountable and uncover waste, fraud, and abuse.

Researchers at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, who have tracked terror incidents and plots since 1994, have found 11 vehicular attacks met the definition of terrorism in 2020, 10 of which were committed by far right extremists and one by a far left extremist. Nine of these were car rammings in which people drove into protests. In the decade prior, they tracked only three such attacks in the United States, including the Charlottesville case; the other two earlier incidents were inspired by ISIS.

Yet, days after Trump vowed to tackle the threat following the El Paso attack, his administration whittled resources away from fighting white supremacist and racist violence. Miles Taylor, former chief of staff to Kirstjen Nielsen, Trump’s third homeland security secretary, recalls sitting in briefings with law enforcement officials, who anecdotally warned that white supremacist extremists were sharing ISIS-car ramming videos as early as 2008. Taylor and other officials at the Department of Homeland Security said they tried to put the president on alert, but Trump’s focus was squarely on border and immigration enforcement.

“Not only did the president not pay attention to it, well into the campaign year, he ramped up his vitriolic rhetoric in such a way that I think it fueled more violence,” Taylor said.

Hobbled by the lack of federal direction and resources, local prosecutors and law enforcement officers have been ill-equipped to understand and counter threats of car attacks. It doesn’t usually fall to them to investigate the social media accounts of car ramming suspects, and they have often taken the drivers’ claims of what occurred at face value. When they do have social media evidence, like in the Fields case, judges don’t always allow it in court.

“Not only did the president not pay attention to it, well into the campaign year, he ramped up his vitriolic rhetoric in such a way that I think it fueled more violence.”

— Miles Taylor, Former chief of staff to Kirstjen Nielsen, President Trump’s third homeland security secretary

In the Globe analysis, at least one driver, in Colorado, had bragged about once hitting a protester on social media in 2017 before he sped through a Black Lives Matter protest in 2020 and hit a demonstrator. He claimed he had been afraid of the crowd surrounding his car, saying one person hit his window with a hammer, and faced a reckless driving charge that was later dropped. Another, a woman from Greenville, N.C., appeared to have published Instagram posts on the Confederate flag and the white race before she hit two Black women protesting a police shooting. She faces felony assault charges, but none for hate crimes. One defense lawyer argued that his client, Michael Ray Stepanek, who intentionally drove into Black Lives Matter protesters in Iowa City, Iowa, had been conditioned by social media and right-wing news to view them as criminals. Stepanek served 76 days in jail but avoided prison time and got a deferred judgment, which means his willful injury charge can be expunged after serving three years of probation.

Five Internet years later — a digital eternity — the car attack meme is now considered ancient and passé. But its core message — that hitting protesters is acceptable — has taken root. Republicans in 16 state legislatures across the country have proposed legislation giving drivers some degree of legal immunity for running into protesters. Most of the bills came amid the Floyd protests, with three of those states enacting laws this year.

A new and ever-replenishing crop of memes remain in circulation, spreading and reinforcing a slew of anti-Democrat, racist, and far right ideas that Trump and his allies helped bring from the fringe to the mainstream. And a sort of meme culture has become pervasive in Republican Party politics, researchers said, as a new generation of politicians such as Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene reproduce the shock value of the online content in hyperbolic and flamboyant stunts.

“This is a simple meme you would find on the Internet but this meme is very real,” she said, referring to a giant copy of a Scooby-Doo meme she brandished on the House floor in September. It featured Fred yanking a green mask labeled “Green New Deal” off of someone’s head to reveal a communist symbol, the hammer and sickle.

In the real world, Charlottesville is still recovering. Heather Heyer’s mother, Susan Bro, said the car ramming and her daughter’s death awakened a lot of people to the threat of white supremacy, but it also put “a white face on a Black issue.”

She is relieved that attention on her daughter has faded, and she has pushed to redirect it to the cause for which Heyer died marching, Black Lives Matter, launching a foundation to provide college and high school scholarships to students passionate about social change.

Caitlin Healy/Globe Staff

In their words

Susan Bro

Charlottesville, Virginia

Susan Bro’s daughter, Heather Heyer, was killed in 2017 when a car drove into a group of counter-protesters at a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va. In her honor, Bro started the Heather Heyer Foundation to provide scholarships to students “passionate about positive social change.”

Bro’s life has been forever altered. She never sits with her back to the door of a restaurant, advice provided by federal law enforcement after she was the target of death threats.

“You would think that the mother of a dead girl would not have to think about that,” she said. But Bro vowed none of that will silence her.

“As long as people divide themselves into us and them, there will be mothers who weep, there will be fathers who weep, for their lost child,” she said.

The city poured millions into counseling services and renamed the street where Heyer was killed “Heather’s Way.” On the four-year anniversary of the bloodshed in August, a makeshift memorial was still standing. Plastic flowers were wrapped around street poles. Messages scribbled in chalk across a brick wall endured.

Gone but not forgotten

Never forget the summer of hate

Hope is action

People dropped off roses and some silently wept. “Her favorite color was purple,” Scott McNabe, 56, a security guard, shared. He and John Loehr, 66, who owned a nearby business, recalled what the city was like before the attack. The site where they stood was not far from where Barack Obama gave a speech and Bruce Springsteen had performed several concerts.

Neither he nor Loehr realized at the time that they were at ground zero of a ghastly trend, that many more protesters would be hit by cars after that.

Sitting on the pavement nearby, Sue Frankel, 57, a program director at an adult education center and activist for more than 30 years, was more than aware of that fact. She had been marching down the street the afternoon that Fields plowed his car into the crowd and was pushed out of the way as people fled. She remembers they had been feeling joyous before the chaos broke out; their march had been cathartic.

“It was like a spontaneous act of celebration and solidarity for us to take the streets and just try to reclaim a little bit of the communal space for something positive,” Frankel said.

After the white supremacist attack, their focus shifted to preventing another such murderous episode. But their efforts have only become more dangerous.

“People have been trying to proclaim truth and justice in the streets for as long as there have been streets,” she said. But now anytime she goes out to protest, she added, she is constantly on the lookout and carries a heavy expectation of impending doom. “Things are less safe.”

Credits

- Reporter: Jazmine Ulloa

- Editors: Elizabeth Goodwin, Jim Puzzanghera, and Mark Morrow

- Photo editor: Kim Chapin

- Director of photography: William Greene

- Video production: Caitlin Healy

- Video production: Caitlin Healy

- Copy editors: Michael Bailey and Mary Creane

- Digital storytelling, design, and development: John Hancock

- Audience experience and engagement: Christina Prignano

- Quality assurance: Chelsey Johnson and Jackson Pace

© Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC