Families, especially those with means, sought to place their frail elders in Belmont Manor, a five-star nursing home. It was a safe refuge for the twilight years, until suddenly it became something else entirely: a case study in the coronavirus's indiscriminate power.

This series was reported by Rebecca Ostriker, Todd Wallack, Liz Kowalczyk, Robert Weisman, Mark Arsenault, and editor Patricia Wen. Today's story was written by Ostriker.

Published Sept. 28, 2020

Third in a three-part series

Belmont Manor looked immaculate. Petunias adorned the nursing home’s sunny front walkway, while hydrangeas nodded in the shade on a recent summer day.

For years, family members felt lucky to get a spot for a loved one here. Tucked in an affluent Boston suburb, the home boasted a five-star rating from the federal government. With its elegant library and dining hall featuring a grand piano, Belmont Manor Nursing and Rehabilitation Center was a rarity, a family-owned facility that felt almost like home. Pricey, too: About $160,000 got you a bed in a double room for a year. And most residents paid their bills out of pocket.

“They were the Four Seasons of nursing homes,” said Lisa Fliegel, whose father spent six years at the Belmont home.

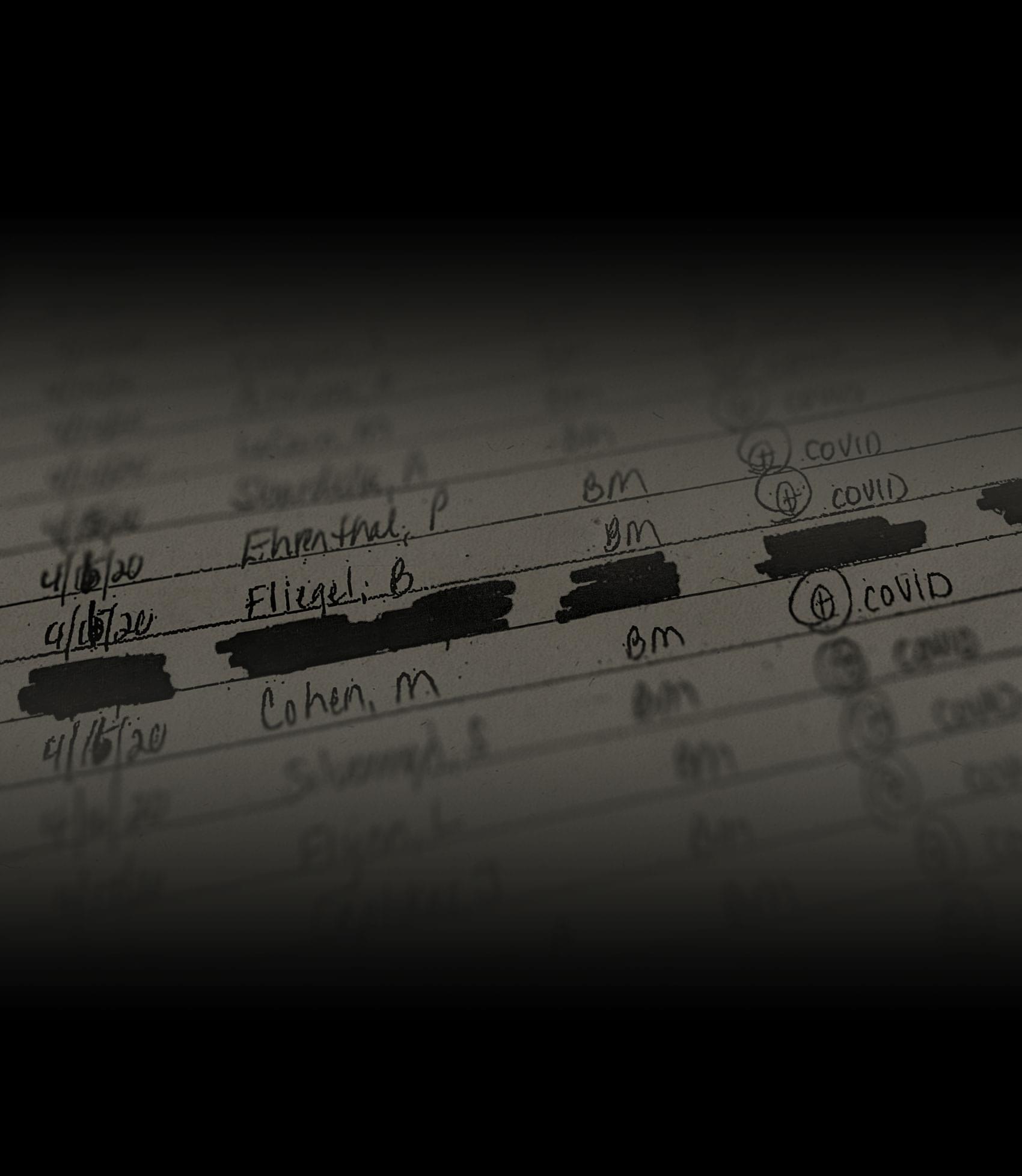

But when the coronavirus ravaged Massachusetts nursing homes, all that money did not buy Belmont Manor’s residents any extra protection: 56 people in the 135-bed facility, including Fliegel’s father, have died from confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infections. That’s more than four deaths per 10 beds. Only one Massachusetts nursing home, located in hard-hit Chelsea, has suffered a higher death rate.

The staggering toll is a case study in the indiscriminate power of this virus and in the failure of the state and the elder-care system to protect some of Massachusetts’ most vulnerable residents. As the virus initially spread inside Belmont Manor, many caregivers weren’t wearing masks. When people started getting sick, the nursing home’s leaders had a less-than-adequate plan to stem the tide. As staffing became tight because of infections and other absences, some employees who tested positive but had no symptoms stayed on the job briefly, while the home’s doctors, to help limit the spread of infection across facilities, did not set foot in the building at the pandemic’s peak.

Town officials were so worried in early April about Belmont Manor’s shortage of testing materials and personal protective equipment they wrote to the state Department of Public Health, urgently asking for help. “[W]e believe that the facility Administrator/Owner is putting at serious risk the lives of all of their residents,” wrote Belmont health director Wesley Chin and David Frizzell, the fire chief at the time.

Ultimately, infection reached nearly every resident; at one point, only six in the building were left unscathed. More than 70 staff members were infected as well.

Belmont Manor’s longtime administrator, Stewart Karger, said that his nursing home was hit with a tsunami of forces beyond his control, and to a significant extent he is right. Caught in an unprecedented health crisis, the home’s leaders were far from alone in their intense but nonetheless ineffective response. Almost 80 percent of Massachusetts nursing homes have seen confirmed or probable COVID-19 deaths, bringing the long-term-care toll to more than 6,000 as of last week — among the highest in the country.

It is just that Belmont Manor, with its strong reputation, seemed to offer more. Families may believe that placing their loved ones in elite nursing homes offers them some greater measure of protection. But a Boston Globe Spotlight Team analysis of about 380 Massachusetts nursing facilities found that well-resourced, highly rated homes fared no better than lower-ranked, less-funded ones in the pandemic. In fact, of the five nursing homes with the highest COVID-19 death rates in Massachusetts, four are five-star homes, as rated by the federal government.

How can that be? The Globe analysis found two primary factors affecting mortality. By far the most powerful is a facility’s location in a high-population area such as Greater Boston, a viral hotspot. Research in multiple states has found location is key: the higher the community infection rate, the greater the risk a worker or visitor will bring the virus into a nursing home.

And once infection enters a building, a second factor comes into play: the number of licensed nurses, who have extensive training in infection control. Staffing is a factor firmly in the control of nursing home management, and Belmont Manor reported licensed nursing hours 20 percent below the state average.

Taken together, the two factors can make a major difference: The Spotlight analysis found that nursing homes in Greater Boston with below-average licensed nurse staffing hours have an average COVID-19 death rate about 50 percent higher than facilities outside that area, with more nurse staffing.

At many cash-strapped nursing homes, a lack of funding undermined efforts to contain the virus, according to industry leaders. But well-resourced homes, including Belmont Manor, didn’t have that excuse. Such homes are far less dependent on Medicaid reimbursement, which pays on average about half as much as private-paying Massachusetts clients. At Belmont Manor, only a third of residents are on Medicaid, while nearly two thirds pay out of their own pockets — one of the highest percentages in Massachusetts — giving the home’s owners an enviable income stream.

How much income? At Belmont Manor, brother and sister co-owners Stewart and Susan Karger, the admissions coordinator, pay themselves handsomely: about $1.6 million and $660,000 in 2018, respectively, according to a state filing.

The Spotlight Team also found evidence suggesting that some Massachusetts facilities may illegally discriminate in order to maintain their financial standing. In an undercover investigation executed in the two months before the pandemic, many nursing homes, including Belmont Manor, appeared to discourage applicants who said they were applying for Medicaid, while responding positively to clients who said they could pay privately for their care, at much higher rates.

Under Massachusetts law, it is illegal for nursing homes that accept Medicaid funding to discriminate against applicants who are on Medicaid or will soon be eligible for it.

Karger defended his leadership, saying that Belmont Manor follows the law on admissions and that because of the home’s corporate structure, “all profits have to flow through to the principals.”

And Karger said that he did everything he could to stop the awful march of COVID-19 through the facility. He echoed Governor Charlie Baker and his top deputies in describing the challenges of combating what Karger called an “invisible monster,” especially when at first, so little was known about how people with no symptoms can spread the virus.

“This was a learning curve, I think, by the entire medical community,” Karger told the Globe in a Zoom interview in July. “It’s very easy to sit here now four months out, and go back and say what we could have, should have done, when we know more today.”

Karger pointed to a series of factors that contributed to the home’s struggles, from a lack of available testing and a nationwide scramble for PPE to ever-changing state and federal guidance.

“We’ve been raked through the coals,” he said. “This wasn’t anyone’s fault.”

Still, some families struggle to understand how a home that seemed to care so much for their loved ones did not do better at keeping them safe.

How could this happen at “a privileged nursing home with all the resources in the world?” asked Fliegel, whose father, Berton Fliegel, was a social worker, professor and community activist. He died at Belmont Manor after being diagnosed with COVID-19, on April 16, at the age of 90.

A manor is made

Stewart Karger grew up in the business, accompanying his father to Belmont Manor as a boy. His father had founded the home in 1967, and after Karger graduated from college in 1979, he started training to become its administrator.

After taking over in 1985, he expanded and remodeled the home, proudly advertising it as “one of the finest facilities in Massachusetts.”

And there were plans to make it even finer. When the pandemic hit, Karger was moving ahead with an expansion plan that would have eliminated several three-bed rooms in favor of singles and doubles. One hope, Karger’s application to the state said, was that rooming fewer residents together would help “with infection control.” Similarly, a new laundry chute would “decrease the risk of cross contamination.”

Both improvements existed only on paper when the novel coronavirus roared in.

Karger described working in elder care as a calling. He savored the “hustle and bustle” at Belmont Manor, he told the Globe, taking a hands-on approach every day.

“The way I administer, I was up on the floors all the time,” Karger said. “I knew every resident, every family. I would go into rooms and talk to residents. If they needed something, you name it.”

Once when residents were being brought to dinner, Karger spotted a food stain on a woman’s sweater. He insisted that then-activities assistant Walker Matzko wheel her back to have her top changed. “Would you want your grandmother to go to a meal like that?” Matzko recalled him asking. “He really puts these residents first.”

Many family members of those who died of COVID-19 at Belmont Manor still praise it highly. They rave about the quality of care, the warm atmosphere, the cleanliness, and the accessibility of management. They appreciated its amenities, from musical performances to lavish holiday celebrations. “The food was expensive things — smoked salmon, shrimp, really nice,” said an Arlington resident whose brother died there in the pandemic and did not want to be named.

“Stewart and Susan have done a spectacular job taking care of my wife over all these years,” said Frederick Childs, whose wife, Beatrice, died of COVID-19 on April 20. “When anything is not perfect, Belmont Manor calls you immediately.”

With the home in demand, the Kargers had many options about whom they could admit.

Marjorie Harvey arrived at Belmont Manor around three years ago. A former social worker, she had a form of vascular dementia that made her nonverbal, her daughter said. She kept injuring herself, and home care just wasn’t working out.

“I had heard it was competitive, but we were lucky to get her right in,” Diane Lulek recalled of her mother, who died April 12.

Harvey could pay privately for her care, said Lulek, and she was not alone among residents’ relatives who believed that made a difference.

Her perception is supported by a Globe Spotlight investigation into potential Medicaid discrimination in nursing-home admissions across the state. Via e-mail, reporters posed as women seeking space for their elderly mothers. Some said their mothers would be on Medicaid, while others said their mothers could pay privately.

And the pattern that emerged from the review was clear: Money talks.

Upon receiving the Spotlight e-mails, Susan Karger told the Medicaid applicant there was a waiting list. “[I]t is always hard to be able to say how long, but at this time, there are a lot waiting,” she wrote. Yet responding to an e-mail from a private-pay applicant two weeks later, she seemed more encouraging: “I would like to talk with you about your Mother’s needs. Please call me, or send me your telephone number so I can call you. Look forward to hearing from you."

Susan Karger declined to comment on the Globe’s findings, and Stewart Karger denied any illegality in a one-sentence reply. “Belmont Manor follows all state and federal regulations regarding admissions,” he said via e-mail.

In 2018, only two of 106 admissions at Belmont Manor were people on Medicaid, a state filing showed. The home’s tilt toward private-paying residents translates into millions in extra revenue. Every day, such residents pay Belmont Manor an average of $450, while Medicaid pays it just $190, according to a state filing.

Karger said in an interview that the home’s high private-pay percentage is because of its location and strong reputation. Most residents, he said, arrive with “a very limited amount of money, and they spend down and they go onto Medicaid.”

One thing is clear, however. With all its revenue, Belmont Manor had below-average levels of licensed nurse staffing.

Much of the crucial work in nursing homes is done by certified nursing assistants, who bathe, dress, and feed residents, among other tasks. But licensed nurses have “a lot more clinical training, especially around issues of infection control, that can really help with proper use of personal protective equipment and other protocols,” said David Grabowski, a professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School.

Lower nurse staffing can mean considerable cost savings: Belmont Manor’s registered nurses and licensed practical nurses now make an average of $33.11 and $31.83 per hour, respectively, compared to $18.40 for its nursing assistants, the home said.

Three former Belmont Manor employees, including a nurse who worked through the peak of the pandemic, said nursing levels were too low, so nurses simply didn’t have enough time to handle their tasks. They might have to rush through shifts, they said, or stay long afterward to finish.

A single nurse often had to handle clinical tasks for a unit of 30 or so patients alone even before the pandemic, they said.

“How can a nurse, a single person, be able to give medication, manage phone calls, talk with the doctors” and address other needs for them all? asked one former staffer who requested anonymity. “That’s where there are shortcuts” such as not washing hands between patients, she said.

In the pandemic, the job only got tougher. “It was very stressful,” said Anthony Romeo Rodriguez, a registered nurse who started working at Belmont Manor just before the COVID-19 deaths began this spring. All four units there soon had just one nurse per shift, he said.

“These are older folks, and the onset of illness is so quick,” Rodriguez explained. “These are people’s lives, they could literally die on your watch. It’s scary.”

“It’s just too much for one nurse to be doing alone,” said Rodriguez, who left after the pandemic’s peak. “There should have been two nurses, especially with the pandemic.”

Certified nursing assistants, many of them immigrants, worked in large numbers at Belmont Manor before the pandemic, bringing overall staffing levels above average. But even they could feel strained as they cared for a challenging population of residents, several former nursing assistants said. Nearly 80 percent of residents have dementia, according to Belmont Manor. “It’s a hard job to do,” said one former nursing aide.

This month, the Baker administration announced nursing-facility reforms, including eliminating three- and four-bed rooms, setting minimum staffing levels, and requiring facilities to spend at least 75 percent of revenue on “direct care staffing costs.” Belmont Manor’s staffing levels now would exceed the new state requirement; it is unclear whether the spending requirement would be more than it now spends on direct-care staffing.

Karger denied his home’s staffing was too low. “At no time have we ever been short-staffed, or required people to rush through their shifts or not to be able to give the appropriate care,” he said. The home’s nursing levels were tailored for its patient population, he explained — mostly older long-term residents with chronic conditions, plus a small percentage of short-term rehab patients who might need intense licensed nursing support.

Dr. David Barrasso, Belmont Manor’s longtime medical director, agreed. “A large number of patients, they need the most intimate of care,” he said. “Those aren’t activities for skilled nurses, they’re activities for nurses’ aides.”

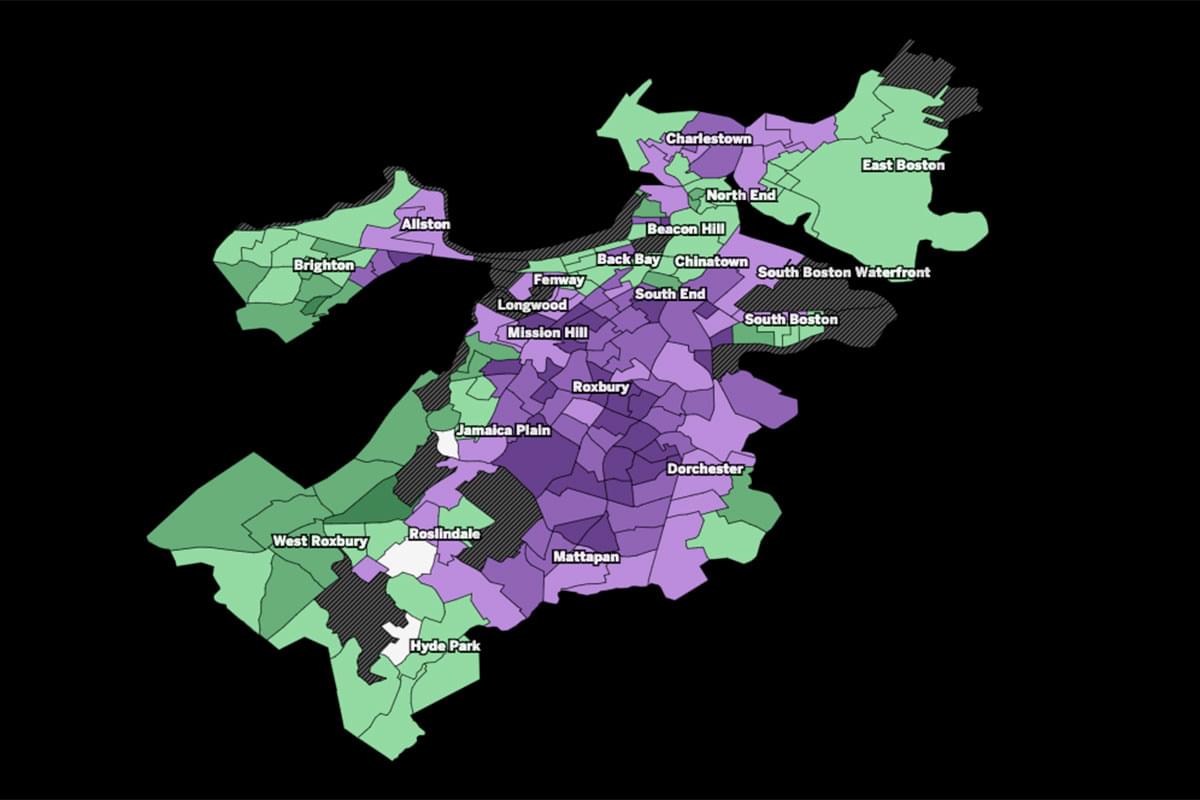

Nearly four out of five Massachusetts nursing homes faced COVID-19 deaths

Death rates varied widely across the state. A Globe Spotlight analysis found geography was the most significant factor related to high death rates. Facilities with the largest cluster of deaths were centered around Greater Boston and other major cities.*

- No deaths reported

- 1-10 deaths reported

- 11-25 deaths reported

- 26-50 deaths reported

- > 51 deaths reported

*The Globe analysis also found a nursing home’s licensed nurse staffing levels were also statistically significant in a facility’s death rate. Many factors were found to have no statistically significant correlation, including its government ratings, its for-profit or nonprofit status, its racial demographics and or its dependence on Medicaid, Medicare, or self-paying residents.

** Cases refer to suspected or confirmed cases among staff and residents. Deaths refer to only death among residents.

NOTES: Map does not include state-operated facilities, including the Holyoke Soldiers’ Home that had a high death toll.

SOURCE: Massachusetts Department of Public Health figures, updated as of Sept. 23, 2020, Belmont Manor data.

Daigo Fujiwara, Tood Wallack/Globe Staff

‘What is your plan?’

By the end of February, news of the pandemic’s spread had grown alarming. An outbreak in Kirkland, Wash., made clear that nursing homes were at special risk.

At Belmont Manor, Stewart Karger had stepped up the home’s cleaning and sanitization regimen. He’d hurried to order personal protective equipment from companies as far away as China and Mexico, though supplies would take about six weeks to arrive.

In early March, Karger’s team assured the Belmont Health Department they were prepared, said Chin, the health director. They began screening for coronavirus symptoms, using a more rigorous standard than the state guidelines, and then closed their doors to most visitors March 12, four days before a state mandate.

But at first, the home didn’t provide masks to all its caregivers. Like many homes, it didn’t have enough.

“If we had used our masks for every single staff member at that point,” Karger said, “we would have run out in a very short period of time.”

Karger and Barrasso were among many who did not initially recognize the threat of asymptomatic transmission. Despite multiple reports in March that people without symptoms were spreading the virus, early guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated, “this is not thought to be the main way the virus spreads.”

“At that time, we never really realized how contagious this was,” Karger said.

“Personally, I didn’t expect there to be asymptomatic transmission,” said Barrasso. “That was a stunner.”

One former nursing assistant recalls being screened and sent home with a high temperature, though he had no other symptoms. He ended up in the hospital with COVID-19. “I was there 33 days,” he said — placed on a ventilator, barely surviving.

By the time Belmont Manor had its first resident with COVID-19 symptoms on March 27, the virus may have been spreading for a week or more. The stricken resident and his roommate were isolated and attended by staff with appropriate PPE.

With the first confirmed COVID-19 case on March 30, records show a DPH epidemiologist told Belmont Manor all caregivers should wear masks.

Town health and safety officials quickly grew alarmed, according to scores of e-mails obtained by the Globe through a public records request.

“We are in desperate need for isolation [g]owns [and] g[o]ggles. We expect to need 5000 gowns,” Karger wrote them March 31.

In a phone call with Karger that day, Frizzell, who oversaw the town’s emergency medical services, learned the home already had two COVID-positive patients, was waiting for 16 test results, and couldn’t get more testing swabs. So Karger “was treating the whole place as being infected and not segregating or isolating any suspected cases,” Frizzell e-mailed colleagues.

The first COVID-19 death came April 1: Philip Milano, a former aerospace engineer, at 94.

In a video conference that day, town officials warned Karger and Belmont Manor director of nursing Mary Murray-Carr they could expect to have multiple daily deaths. “What is your plan?” “Don’t really have a plan haven’t thought of it” was the gist of their reply, according to notes taken by Frizzell, who recently retired as fire chief.

“What happens if you lose up to 50% of your staff?” Their response, according to the notes: “Don’t really know what they would do and asked us for suggestions.”

The next day, Frizzell wrote to colleagues, “I didn’t get much sleep last night thinking about the situation at Belmont Manor.”

Town officials were so worried they sent a “Letter of Concern” on April 2 to the state, asking for help with testing. By that point a dozen symptomatic patients had been moved to a dedicated COVID-19 wing, but four others remained in a locked dementia unit, and the home couldn’t test more.

All suspected COVID-19 patients were isolated the next day, and the National Guard tested residents April 5, but only those with symptoms.

Soon, shortages of staff and PPE reached critical points, officials said. The state would send thousands of items from its emergency stockpile. But on April 14 Belmont Manor was down to just 100 gowns, little more than enough for a day, e-mails show.

That day, Lisa Fliegel came for an end-of-life visit with her father. Like most Belmont Manor residents, he had a do-not-resuscitate order. “You have two minutes to come and say goodbye,” she said the home told her.

Two minutes turned into five hours.

The place was “totally understaffed,” she recalled. They “forgot I was there.”

During her visit, “there were people screaming in pain and confusion the entire time I was there,” she said.

Rodriguez, the former Belmont Manor nurse, remembers that tumultuous time well. Caregivers typically wore the same surgical mask and gown all day, going in and out of COVID-positive and COVID-negative rooms, he said. By mid-April, he recalled, they went on an honor system to check their own temperatures.

On April 15, Karger e-mailed a startling update, writing to families “with a heavy heart.” He said 116 residents had tested positive, 30 had died, and 59 of about 190 employees were infected.

Alerting town officials the next day that there weren’t enough staff for the evening’s shifts, Karger closed a unit and consolidated patients. “They are in urgent need of help from DPH,” Chin told a regional emergency planner.

At a press briefing April 16, Health and Human Services Secretary Marylou Sudders said, “We are actually sending in our technical assistance SWAT team to help them figure out what they need to be doing at Belmont Manor.”

Yet once the tidal wave of infection had breached its doors, Belmont Manor was overwhelmed. By April 17 — less than three weeks after the first confirmed case — only six residents were left uninfected, Karger’s team told state monitors. Nearly two-thirds of the 114 staff who had been tested were COVID-positive as well.

As the death toll hit the headlines, Karger hired Denterlein, a public relations firm. And some officials mobilized to help solve a temporary weekend staffing crisis.

Matters came to a head at the state monitoring visit on April 17, when surveyors discovered that multiple employees who’d tested positive but had no symptoms were continuing to work. Karger was relying on special CDC guidelines that allow for that step when facing a staff-shortage crisis.

But the DPH representatives told him no, all COVID-positive employees had to refrain from work for 10 days after their tests. Karger’s team warned that if they had to exclude those employees from work, "they would potentially have to evacuate the building as they would not have enough staff to safely care for residents,” surveyors reported.

State Senator William Brownsberger appealed to state authorities for help. Though the Baker administration says no exceptions were made, Brownsberger said a solution was reached. Some asymptomatic COVID-positive staff worked through the weekend, but only with COVID-positive patients, Belmont Manor told the Globe through a spokesperson.

“Reason prevailed,” Brownsberger said. “You had a facility where basically everyone had COVID, so sending people home with COVID would not be the right decision. DPH was asking the impossible. … We were able to reach the right people at DPH and they were able to clarify."

Rodriguez, the registered nurse, remembers other challenges adding up. A lot of the health records were kept on paper, not in an electronic system, he said. And he never saw the home’s doctors during the pandemic’s peak: “They never came to the facility. It was all over the phone.” That meant nurses might have to wait for a doctor to call back, he explained, and doctors couldn’t see the patients’ charts.

Karger said Barrasso and Belmont Manor’s associate medical director “provided care using telemedicine, including bedside visits via FaceTime or Skype, for most of the pandemic to avoid inadvertently spreading infection across facilities.”

Even as the number of deaths finally began to dwindle, more bad news came: The home was cited for two “core” deficiencies at a state infection-control audit May 15, including the location of a station for donning and doffing PPE.

Karger said a second citation involving separating COVID-negative patients from others was an auditor’s error. And at the next audit, Belmont Manor got a perfect score. “Today, Belmont Manor is COVID-19 free,” Karger recently told the Globe.

Still, the grueling weeks have left an emotional mark.

“It was horrendous. It was horrible,” Karger said. “It is just something that I will never get over. You reevaluate your life when you’re going through this. I am pushing forward, but it’s really tough.”

Some bereaved family members still puzzle over what happened. The home was known for its warm atmosphere — compassionate caregivers, and a schedule packed with hands-on activities. Could all that have initially helped spread the virus?

“Because they’re such an affectionate, caring group is the only way we thought perhaps that’s how it spread,” said Karen Haroian, who used to visit her mother, Barbara Jutstrom, every evening for dinner. She died April 9. “They would hug my mother! They would give her a little kiss on her cheek.”

Chin, the town’s health director, said he now believes Belmont Manor’s leaders did their best “based on the little guidance they had” from state and federal authorities. Without government acknowledgement of the extent of asymptomatic spread, Chin said, “we were all operating in the dark.”

And Karger insisted the extremity of Belmont Manor’s death toll was due to forces beyond his control. His home was exposed early on in the pandemic, he said, when there were nationwide shortages of PPE. Because the National Guard would not test nursing home staff or asymptomatic residents at first, and test results took multiple days to come back, it was difficult to evaluate risks and determine who was infected.

“We simply did not have the information we needed to cohort patients and provide the right PPE to staff,” he stated in an e-mail.

Any suggestion “that Belmont Manor could have avoided the ravages of this pandemic with additional financial investments (past or present) or staffing is unsubstantiated by any facts,” Karger added via e-mail. “We have consistently invested in the staff, physical infrastructure and equipment necessary to provide outstanding care.”

He emphasized that throughout, he did what experts told him.

“We felt we followed every protocol possible for what we knew,” Karger said. “The guidance was changing on a daily basis from DPH. And it was very difficult.”

The value of caring staff

Belmont Manor was not the only highly rated nursing home to be hit hard. Others were also operating in high-population areas with relatively low nurse staffing levels.

Among the five facilities with the state’s highest coronavirus death rates, two other five-star homes had below-average licensed nurse staffing levels. The Katzman Family Center for Living in Chelsea has a COVID-19 death rate of 46 per 100 beds, the state’s worst. At Coleman House in Northborough, there have been 38 deaths per 100 beds.

The Katzman Family Center started widespread testing early in March, so it identified cases and attributed deaths to COVID-19 “much earlier than other facilities,” Adam Berman, president of Chelsea Jewish Lifecare, which operates the facility, said via e-mail. He also said the home, located in the COVID-19 hotspot of Chelsea, kept its doors open to COVID-positive admissions at the pandemic’s peak.

Berman noted that the home’s four-star overall staffing rating is above average. The administrator of Coleman House, which has a two-star overall staffing rating, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Staffing is one of three categories that make up the federal ratings from the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and it’s the most reliable because it is based on payroll records, said Richard J. Mollot, executive director of the Long Term Care Community Coalition. “Those are the best data we have.”

Several recent studies also suggest more nurse staffing can help contain COVID-19 in nursing homes. Dr. Jose Figueroa, assistant professor at Harvard’s T. H. Chan School of Public Health, and colleagues found that in eight states including Massachusetts, staffing was the only ratings category linked to fewer COVID-19 cases. “It’s called a nursing home for a reason, right?” said Figueroa.

Lisa Fliegel fondly remembers Belmont Manor’s caring staff. And her April 14 end-of-life visit remains fresh in her mind.

For years, she’d made weekly visits to see Berton Fliegel, treasuring time with the man who, as his death notice stated, “devoted his career to fighting on behalf of the poor.”

It was two days before he died. She found him in a delirium. Fliegel prayed and sang, and gave him lemon-flavored water. “He’s just writhing and screaming and tearing at his clothes,” she recalled. She asked staff to give him more morphine, and they spritzed some medicine under his tongue.

A woman came to bathe him and change his clothes. As the caregiver undressed and washed him, Fliegel told him, "This woman is doing this out of love.”

“It was painful and awful,” Fliegel said of her father’s suffering. But thinking of the predicament of so many front-line workers, “I almost felt more horror for the woman who was taking care of him than him.”

Thinking back now on what might have gone wrong at Belmont Manor, Fliegel believes it was hubris: The home’s leaders didn’t realize what they didn’t know, she said. The thought struck her anew when she returned after her father’s funeral.

She sat on the grass, as staff offered condolences.

“A Hispanic man who works in facilities came out with a cart of my dad’s stuff,” Fliegel said. Even his toothbrush and respiration machine, with the mask he’d worn.

She had asked for everything but was shocked to see items certainly exposed to the virus. And she worried for the worker.

By that day, almost all the residents were infected. And “the guy didn’t have a mask on,” she recalled. “He wasn’t wearing gloves.”

Rebecca Ostriker can be reached at [email protected]. Any tips and comments can also be sent to the Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected] or by calling 617-929-7483.

The entire three-part Last Words series can be found at www.bostonglobe.com/lastwords.