Quite the contrary, a Spotlight investigation shows. Death exposes in high relief the layers of inequities, in race and income, care and opportunity, that shape life down to its final hours. It is a truth the pandemic has only underscored — one hard to see, because it is so much easier to look away.

This series was reported by Mark Arsenault, Liz Kowalczyk, Todd Wallack, Saurabh Datar, Rebecca Ostriker, Robert Weisman and editor Patricia Wen. Today's story was written by Arsenault.

Published Sept. 26, 2020

First in a three-part series

CHICOPEE — No one thought Janet would die first.

Why would they? Her husband, Lowell, was the one who had the heart attacks and the blood clots; the one with diabetes and swollen legs numbed by disease; the one who spent the past 12 years in a wheelchair.

But it was Janet Gottsman, a housekeeper, who developed metastatic colon cancer. And in January 2019, it was Janet who lay on her deathbed in BayState Medical Center, Springfield. She was 62 years old.

Like most Massachusetts residents at the end of life, she was dying someplace she did not want to be.

Janet wanted to go home, home with Lowell, home to the tiny Chicopee apartment where they would sit side-by-side in overstuffed easy chairs, below the sultry gaze of a young Elvis Presley from a wall tapestry picked up at Graceland some decade past.

“I told them, the doctor, ‘Just send her home, I can take care of her,’" Lowell said. “He was like, ‘You’re in a wheelchair.’"

Hiring an aide to provide 24/7 care was unaffordable. A luxury hotel would have been cheaper by the day.

Lowell saw his wife in the hospital on a cold winter Monday. She was awake but delirious, he said. At the end of his visit, he hugged her and gave her a peck goodbye. “I love you,” he whispered, the last thing he ever told her. Lowell had just gotten home when the call came. Janet had died.

Left unsaid, it was the kind of death that nobody, certainly not Janet, would have chosen.

But it was the kind of death all too typical for people who work hard jobs for modest pay. They tend to die too young, and to die too hard.

In 2019, the Boston Globe Spotlight Team set out to research death in Massachusetts, to determine the effect of wealth and race on how long people live and how and where they die. This investigation involved an unprecedented statistical review of the information contained on 1.2 million death certificates, covering every Massachusetts death back to 1999. We surveyed by mail more than 450 families that had recently lost a loved one, asking specific questions about the end-of-life care their loved one received. And we collaborated with Suffolk University on an unusual survey, polling public opinion on issues related to death and dying.

The findings were stark and striking. Here, in a progressive state that boasts some of the world’s greatest hospitals, poor people live shorter lives, much shorter, than those with money. Black and Latino patients get less hospice care, die with more pain, and suffer more early deaths than do white and Asian people. People who are Black, Latino, or poor die more often inside sterile hospitals, while the wealthier have long had better access to residential-like alternatives.

We found that in addition to a lack of good options for everyone, there is often a lack of trust; for Black patients, especially, end-of-life planning to avoid an overly medicalized death raises suspicions about not getting enough care.

Thinking deeply about death does not come naturally. It is easy to look away. But in that uncomfortable blind spot, inequities are growing unchecked.

And then, as the Globe prepared to publish its findings early this year, the global pandemic crashed over Massachusetts, in a wave of death shocking in its scale. COVID-19 was the hundred-year storm that confirmed trends that had been quietly building for decades.

Death has long been called the Great Equalizer. This investigation says no, in fact it is not. The same inequities that complicate life for so many people can also determine when and how they die. That’s the case before the pandemic, throughout the virus’s spring rampage, and, without hard changes, long after the disease is out of our lives.

The longevity gap

Lowell Gottsman is 68. He wears Janet’s wedding ring and a vial with a pinch of her ashes on a chain around his neck. They met as kids, marrying in 1974, practically the moment Janet turned 18, he said. They were a bit of an odd couple in that he was this big, barrel-chested guy and she was 4-foot-10. Friends called them Mutt and Jeff. They had two children, now grown up and living in other states.

Lowell’s old apartment, the last place he and his wife lived together, is in one of the poorer census tracts in Massachusetts; the neighborhood’s 2018 median household income was $32,500, less than half the state average.

And across these lower-income neighborhoods, life is shorter.

In 2019, before the pandemic, the median age of death in low-income areas was 75, three years lower than it was in 2000 and five years beneath the statewide median of 80. The median refers to the age at which half the deaths were younger, half were older.

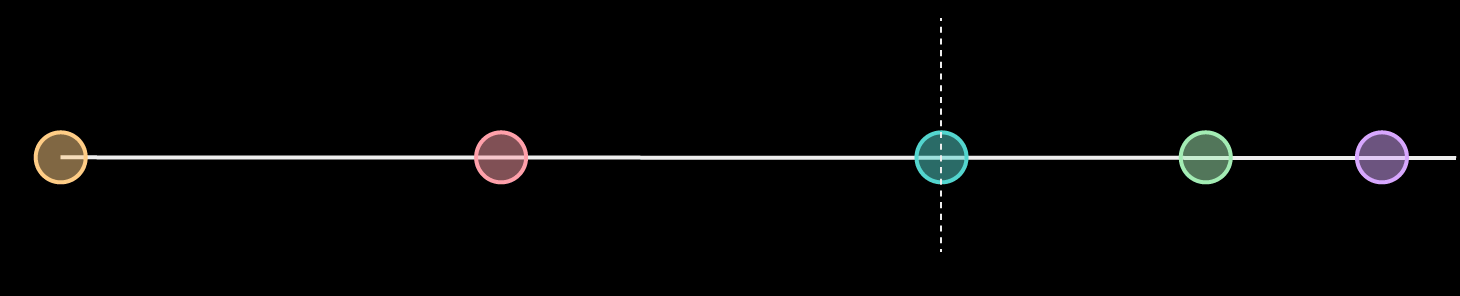

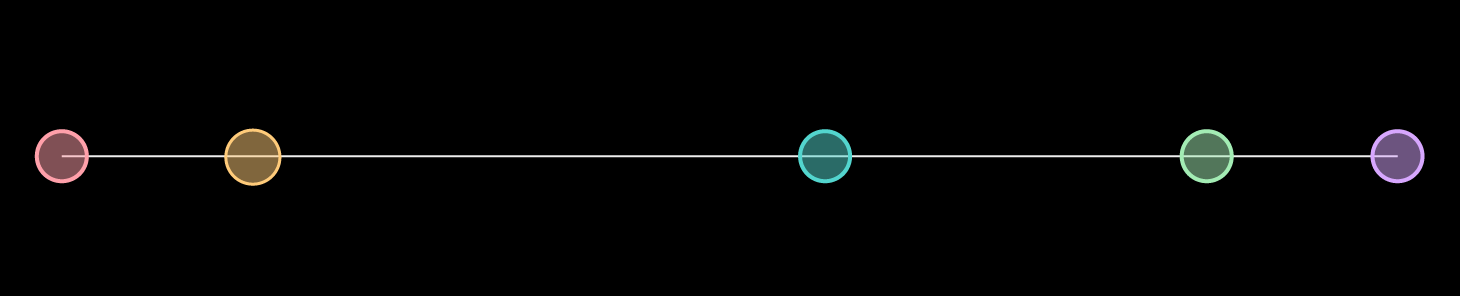

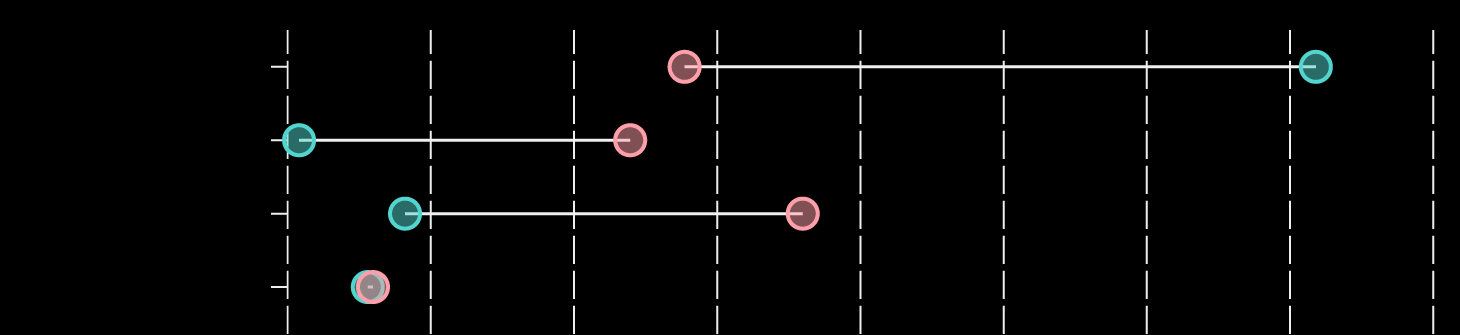

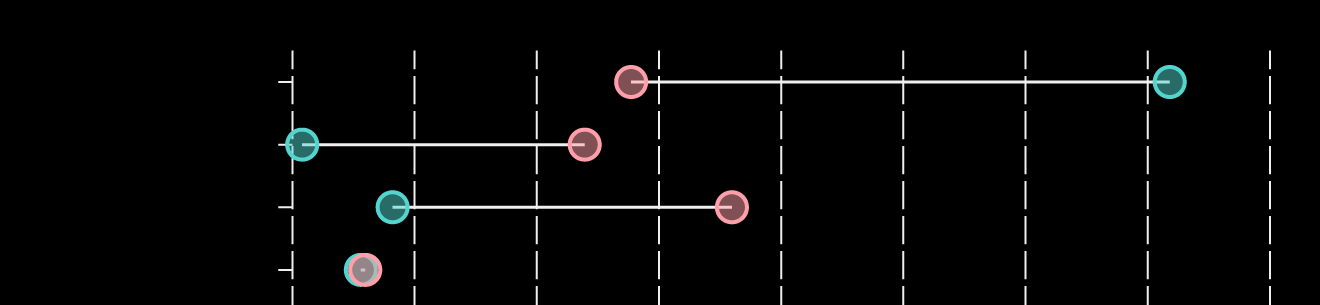

The life gap

People from high-income neighborhoods in Massachusetts last year overall lived 15 years longer than those from poor neighborhoods.

High

income

Very low

household

income

Low

income

Middle-low

income

Middle-high

income

70 years

75 years

80 years

83 years

85 years

State median age of death

Middle-low

income

High

income

Very low

household

income

Low

income

Middle-high

income

70 years

75

80

83

85

State median age of death

High

income

85 years

Middle-high

income

83 years

State median

age of death

Middle-low

income

80 years

Low

income

75 years

Very low

household

income

70 years

High

income

Very low

household

income

Low

income

Middle-low

income

Middle-high

income

70 years

75 years

80 years

83 years

85 years

State median age of death

High

income

85 years

Middle-high

income

83 years

State median

age of death

Middle-low

income

80 years

Low

income

75 years

Very low

household

income

70 years

NOTES: The Globe's income designation and other methodology can be found at the end of the article.

SOURCE: 2019 Mass. Department of Public Health death data

Saurabh Datar/Globe Staff

The connection between poverty and a shorter life is even starker in the extremes. In the 50 poorest Massachusetts census tracts — neighborhoods of Brockton, Worcester, Boston, and Fall River, among others — the median age of death was 70.

On the other end, we see the effect of wealth. In the 50 richest — parts of Lexington, Newton, North Andover, and others where household income was above $160,000 — the median age of death was 85.

We also looked at death and income in a second way — by life expectancy estimates, such as those used by public health experts and insurance companies — and the trends are similar. In the highest income areas of Massachusetts, life expectancy is 84 years, meaning that a baby born today could be expected to live to that age if current death rates remained steady.

Life expectancy declines with a neighborhood’s income level, stepping down like a ladder. At the bottom, in neighborhoods in which household income is very low, below about $31,000, a baby born today would be expected to live just 76 years.

Call it a life-gap. Or a time-gap. People from poorer areas of this state have less time to achieve what they want from their lives.

Precisely why people from poor areas die younger is not entirely understood. Those with money can afford better medical care, of course, including regular preventative care that may catch problems earlier. Education and behavior — stress management, exercise, nutrition, and smoking — may also play a role.

To produce these and many of the statistics in this series, the Globe filed voluminous state records requests, and won a public records lawsuit against the Department of Public Health, to assemble a database of Massachusetts deaths from 1999 to mid-2020. For select years, we matched the home addresses of every resident who died within the state to the median household income of each decedent’s census tract, an area more granular than a zip code and that typically contains between 1,000 and 8,000 people. These income estimates were then aggregated into an economic portrait of death in Massachusetts, which can be analyzed by race, income, sex, age, occupation, and even cause of death.

Median age of death is not an effective statistic to directly compare the longevity of each race or ethnic group in Massachusetts, largely because the white population is much bigger and older. Immigration patterns and birth rates contribute to the relative youthfulness of the Black and Latino populations, affecting death rates. Still, in an analysis of the data, nuanced findings emerge.

In recent years, the death rates for older Black and Latino people in Massachusetts have dropped below those of white people, who have seen a rise in opioid deaths and suicides. But Black and Latino families still bury a far greater proportion of their children, due to higher death rates at younger ages than in white and Asian families. That means more cases of infant mortality, more heartbreaking funerals for children and teenagers.

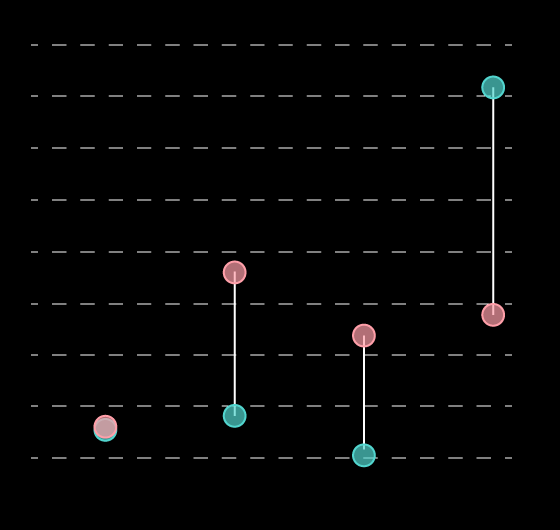

Deaths across the lifespan

Scroll across the chart to find deaths in Massachusetts at each age in the past two decades, broken down by race. This chart does not reflect current life expectancy, but a snapshot of past deaths. Since 1999, younger deaths, including in infancy, occurred more often in Black, Hispanic and Asian populations, while more white people died at older ages, reflecting in part a much larger elderly white population.

NOTES: Deaths over age 100 are excluded in this chart.

SOURCE: Massachusetts Department of Public Health death data

Kevin Litman-Navarro and Russell Goldenberg for The Pudding.

In 2018, for instance, the death rate for Black children from birth to age 5 was nearly three times that of white children. Death rates for Latino children of that age were about 24 percent higher than those of white kids.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, bringing new disparities.

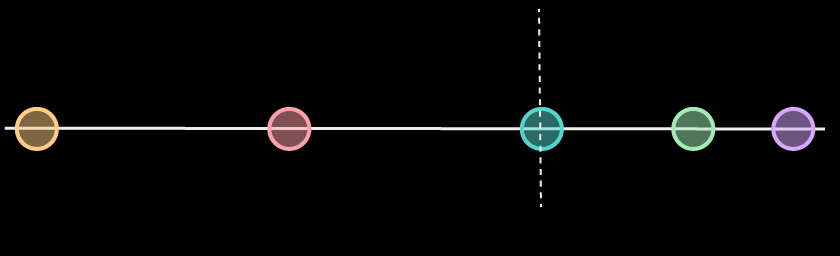

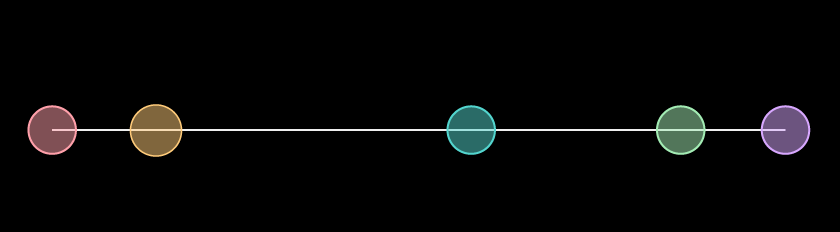

COVID-19 was a cause or contributing factor in 20 percent of Massachusetts resident deaths from January to early July in 2020.

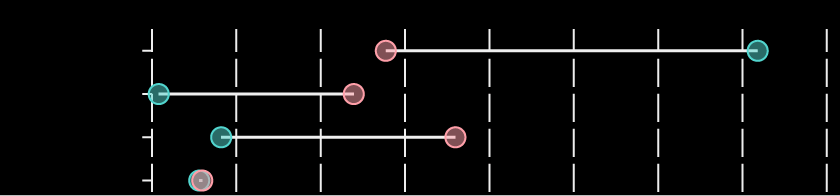

In wealthy areas of Massachusetts, the median age of death for COVID patients was 87, about seven years older than patients from low- and very-low income areas.

People with COVID-19 from low-income neighborhoods died seven years younger than those from wealthier areas.

High

income

Low

income

Very low

income

Middle-low

income

Middle-high

income

80 years

81

84 years

86 years

87 years

Middle-low

income

High

income

Low

income

Very low

income

Middle-high

income

80 years

81

84

86

87

High

income

87 years

Middle-high

income

86 years

Middle-low

income

84 years

Low income

Very low

income

80 years

81 years

High

income

Low

income

Very low

income

Middle-low

income

Middle-high

income

80 years

81

84 years

86 years

87 years

High

income

87 years

Middle-high

income

86 years

Middle-low

income

84 years

Low income

Very low

income

80 years

81 years

NOTES: Details about the Globe's income designations and other analysis can be found in the methodology box at the end of the story.

SOURCE: Mass. Department of Public Health death data

Saurabh Datar/Globe Staff

The pandemic also killed Black and Latino residents at sky-high rates. In the first six months of this year, deaths among white residents were up 24 percent over the same period in 2019, reflecting the pandemic’s deadly sweep. In raw numbers, more white patients died from COVID than Black and Latino patients.

But deaths this year were up an astounding 59 percent among Black residents in the same six-month time period; among Latino residents, deaths were up 46 percent.

The virus also introduced a new variation of inequity, the Spotlight statistical analysis shows. By affecting more people in hands-on, blue-collar jobs that cannot be done from home, COVID deaths were especially striking among people of color who fill many of these jobs.

Just 7 percent of white patients who died of COVID by early July were of working age, younger than 65.

Among Black residents who died from COVID, though, 20 percent were people under age 65; for Latino residents, the figure was higher, 28 percent.

For more than 20 years, Rosanna Wilson worked one of those jobs that cannot be done at home. She was a nursing assistant, most recently at East Longmeadow Skilled Nursing Center. She was born in Jamaica in 1962. Her parents immigrated to the United States first and then sent for their grown children.

Living in Western Massachusetts, Rosanna married, raised children, and scraped up enough savings to buy a house in Springfield. She routinely worked long hours for overtime pay “to save up for the bills,” said her daughter, Antoinette. Rosanna made “$16 to $17” an hour for intimate and unglamorous work: bathing patients, changing diapers, helping people use the bathroom, getting the patients in and out of wheelchairs, making beds.

“She came from a third-world country,” Antoinette said. “It was the best job she could get.”

As the pandemic intensified in the spring, Rosanna’s sister, June Campbell, urged Rosanna to stay out of the nursing home.

“I wish she wasn’t working there,” June said. “She didn’t get good protection.” She cared for residents while wearing “a little blue mask … like a piece of paper.” But Rosanna insisted on completing her assigned shifts. Officials at the facility say the staff was “well-protected” and had access to PPE, including gowns, gloves, and KN95 masks, and was trained in using them.

Rosanna’s daughter said her mom became “overworked” and that stress over money had worn her down. “Income can determine how well you take care of yourself,” she said. “If you’re not making enough to make ends meet, you’ll have a suppressed immune system.”

She also worked in a facility with coronavirus, like so many Massachusetts nursing homes. Twenty-four patients of East Longmeadow Skilled Nursing Center have died of COVID-19 as of late August, according to state figures.

After working a shift this spring, Rosanna felt chilled. She went to the hospital, got a COVID test, and was sent home to wait for results, her family said. By the time the test came back positive, she was laboring to breathe and her blood oxygen was low. She was admitted into Bay State Medical Center in Springfield.

Doctors ultimately recommended she be placed on a ventilator. She did not want to be suspended in an induced coma with a tube down her throat. She told her family: “I don’t want to die like this.”

Medically, though, it was her last chance, and she took it.

Rosanna died May 15. She was 58.

Where hospital systems fall short

A surgeon gave Gertha Sanon’s family the hard news at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Boston, a for-profit hospital owned by Steward Health Care. Her gallbladder cancer had spread. She likely had just weeks to live.

That would have been a good point to send in a doctor who specializes in palliative care — a hallmark of hospitals dedicated to helping patients with serious illnesses — to talk with the 72-year-old Haitian immigrant. These specialists treat pain and stress and guide important decisions, including whether to enroll in hospice. Palliative care can tremendously improve the life of someone fighting a serious illness, but the Globe analysis shows it is not always provided.

St. Elizabeth’s doesn’t have an inpatient palliative care program. In fact, none of the nine Steward hospitals in Massachusetts employ specialized credentialed palliative care doctors, including Good Samaritan Medical Center in Brockton, where Gertha was rushed twice in her final anguished weeks of life.

Even as her cancer progressed and her symptoms worsened, Gertha, a Brockton resident, never saw a palliative care specialist, according to her daughters and medical records. And she never saw a hospice worker until the day before she died at Good Samaritan in 2016.

“She was in agony and I don’t think it was called for,’' said her youngest daughter, Guerline Ulysse-Bel-Amour. “The pain was really brutal.‘'

Steward would not discuss Gertha’s care, citing privacy concerns. A company spokesperson said that it is working to establish palliative care programs in its hospitals and that the service is often offered to patients through outside providers in its network.

For an overwhelming majority, the concept of pain at the end of life is unendurable. Seventy-five percent of Massachusetts adults say they would want doctors to stop treatment and let them die if they had an incurable disease and were in terrible pain, according to the Globe/Suffolk poll.

Pain is treatable with palliative care. Yet nearly 20 Massachusetts acute care hospitals — one out of three — do not have robust inpatient palliative care programs, a Globe survey found. And three out of four of these hospitals rely heavily on revenue from Medicare and Medicaid, the government insurance programs for the elderly and the poor.

The Massachusetts Legislature tried to make hospitals more accountable on this important measure of services, passing a law in 2012 requiring them to give patients information about palliative care. But hospitals do not always comply and the state Department of Public Health does not closely enforce the requirement, the Globe found. In the five years since the rules took effect, the health department, as of early this year, had never cited a hospital for failing to follow them.

The hard work of dying

Dying at home has become so idealized, it is easy to imagine if we dare. There we lie our older selves, encircled by generations of family gathered to say goodbye. The music of our youth plays softly in the background. We feel no pain. Only love. Death notices have a shorthand for this sort of death, almost like bragging: She died peacefully at home surrounded by loving family.

It is where most people would prefer to die. Fully 72 percent of Massachusetts adults said they would rather die at home than a hospital or other institution, according to the Globe/Suffolk University poll.

Research published last December in the New England Journal of Medicine said that for the first time since the mid-20th century, more Americans were dying at home than in a hospital. But that is not true in Massachusetts. Before the COVID outbreak, it ranked 44th among states in the percentage of home deaths, according to a Spotlight analysis of 2018 CDC data.

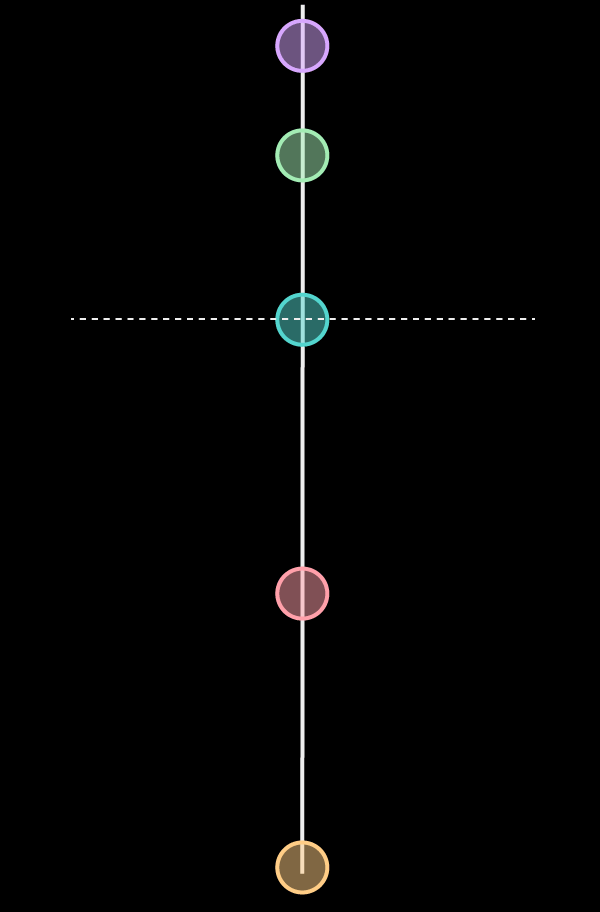

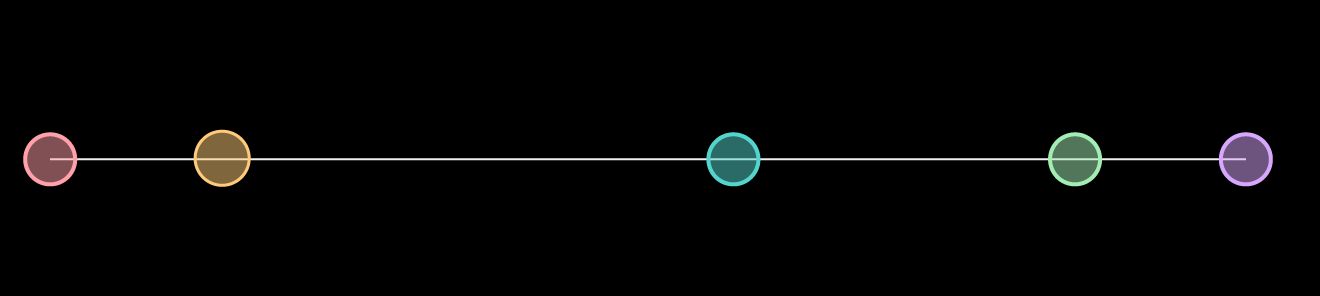

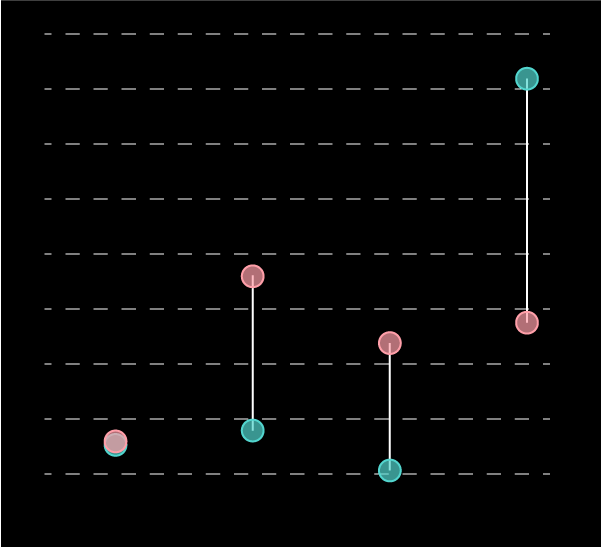

Not many get the death they want

Poll: Nearly three out of four people would prefer to die at home, but chances of a home death are only one in four.

Actual percentage of people in 2019 who died in this location

RESIDENCE

NURSING HOME

HOSPITAL

HOSPICE FACILITY

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Percent

RESIDENCE

NURSING

HOME

HOSPITAL

HOSPICE

FACILITY

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Percent

80 percent

RESIDENCE

70

60

50

40

HOSPITAL

30

HOSPICE

FACILITY

20

NURSING

HOME

10

0

RESIDENCE

NURSING HOME

HOSPITAL

HOSPICE FACILITY

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Percent

80 percent

RESIDENCE

70

60

50

40

HOSPITAL

30

HOSPICE

FACILITY

20

NURSING

HOME

10

0

SOURCE: Boston Globe/Suffolk University poll in 2019; Mass. Department of Public Health death data.

Saurabh Datar/Globe Staff

Only about a quarter of people die at home in Massachusetts, with little difference among income groups, according to pre-pandemic numbers. The national average was 31 percent; Utah led the nation with 52 percent of deaths occurring at home.

Dying at home can require the heroic commitment of close family or friends to provide often round-the-clock intense care. That can be tough or impossible if family members cannot take time off from their jobs, or if they are unable to keep up with the needs of a dying patient.

Money, for those who have enough, can make a difference in arranging a home-like alternative to dying in a chaotic hospital.

Lee Cowgill and his partner, Stanley Michalik, came from humble backgrounds, but both worked in good jobs and by late career earned a comfortable living. “We did have financial resources a lot of people wouldn’t have,” Lee said.

They stashed away extra savings over the last two years of Stanley’s life, as he fought lymphoma.

In late 2017, Lee brought Stanley home from the hospital, to Quincy, for the last time.

Lee was 60 then, working as IT director at the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program. Stanley was 78, a retired physician’s assistant at Tufts New England Medical Center.

After 27 years together, the men had a deep talk about how Stanley’s last days should go, and both agreed that there should be no heroic measures, no medical machines.

And that Stanley would be home for hospice.

It is a common misconception that hospice is a place we go to die. Hospice is a comfort care service for the dying and their families. It can take place inside a stand-alone facility but is often a service brought to people’s homes, overseen by doctors and nurses and other professionals in periodic visits and phone calls, with family members handling the daily, or even hour-to-hour, care.

The first day of Stanley’s hospice was nearly a disaster. He slipped out of a chair and Lee struggled to get him up off the floor. “I realized if I wrenched my back it would be game over,” Lee said. Who else could provide the care?

Lee hired a home health aide, three days a week. It cost $28 an hour, almost $700 a week. The aides bathed Stanley, kept him clean, fed him, made sure he was turned in the bed — the same things Lee would do — but just their presence gave Lee time to get out of the house occasionally for groceries. If Stanley had to be moved, Lee sometimes waited until an aide was around to help.

The assistance was so valuable that if Lee could do it over, he would have hired full-time aides. The problem was, he didn’t know how long he would need the help. Stanley died after about 10 days in hospice. What if it had been 10 months?

When providing home care becomes too hard, people with means will find alternatives, such as hiring help or moving their loved one to dedicated nursing homes and hospice and assisted-living facilities. The growing trend of more people moving into — and dying in — assisted-living facilities is primarily driven by white and more affluent patients.

For the poor, the alternative more often is dying in a hospital.

In 2019, 41 percent of Massachusetts deaths among people from low-income areas occurred in a hospital, with many of those patients hooked to machines and tubes. That figure includes the 9 percent who died in emergency rooms.

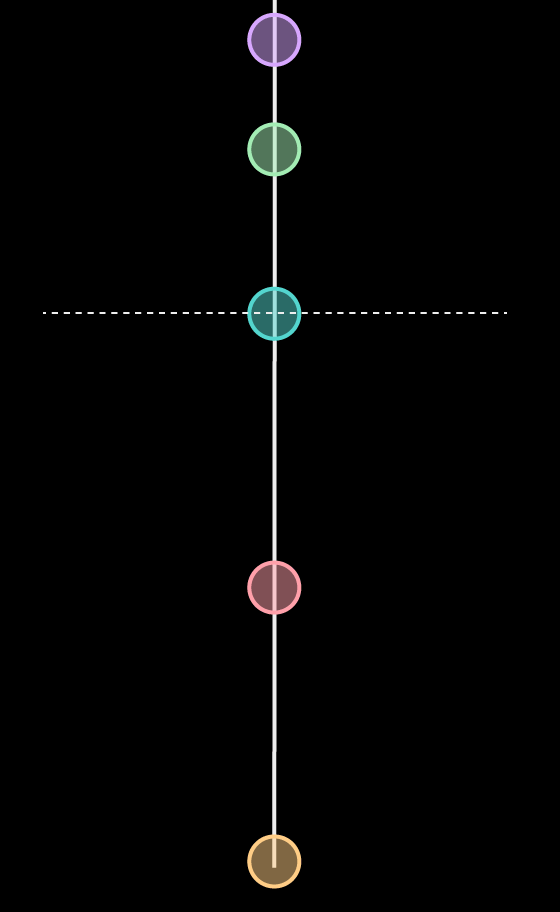

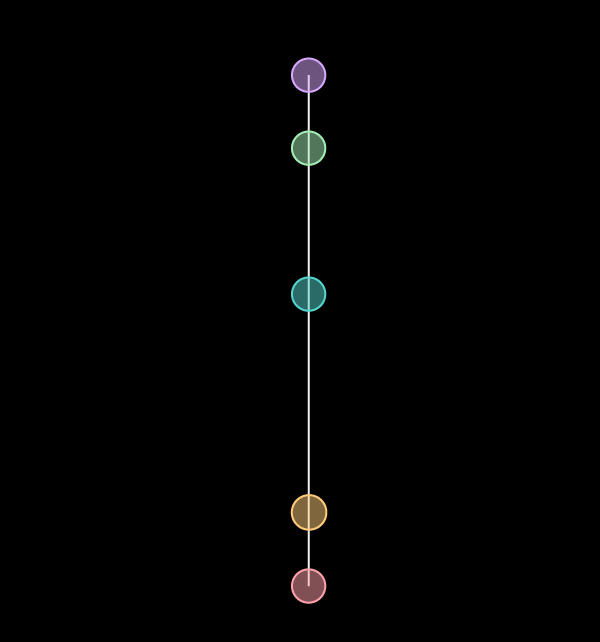

People from poor areas more likely die in hospitals

People from higher-income areas have a better chance of dying in home-like settings, such as assisted living and hospice.

Where people died in 2019 by income

NOTES: The Globe's income designations and other methodology can be found at the end of the story.

SOURCE: Mass. Department of Public Health death data

Kevin Litman-Navarro and Russell Goldenberg for The Pudding

Among patients from wealthy areas, just 30 percent died in the hospital, including 5 percent in emergency rooms.

Patients of all income levels died in greater numbers in hospital care during the pandemic, but the trends held true: People from poor areas were more likely to die in a hospital.

The coronavirus plague all but obliterated dreams of a peaceful home death: Just 2 percent of COVID patients across all incomes died at home. COVID patients who could not be saved in hospitals were not sent home to die, due to infection risks.

Thomas Davis, an 80-year-old Air Force vet from Boston, was one of the few COVID patients who did die at home, on April 15 at the height of the pandemic in Massachusetts. Tom’s wife for 27 years, Ellen Strickland, said she faced a dilemma with her husband’s end-of-life care: She had the money to hire help, but the risk of COVID infection made it difficult to find somebody who could help her. It was like not having any money at all.

“Oh my God, it was hell,” she said. Yet despite the difficulty, she was reluctant to call an ambulance. With COVID rules restricting hospital visits, she knew she would never see him again. He might die alone. “He would think I had abandoned him.”

Racial differences in end-of-life care

For some, part of end-of-life care is deciding when to forgo treatment — the drugs, the hospital visits, the scans and machines — for the sake of savoring whatever time is left. The “good death” movement is gaining ground, as more patients push back against overly medicalized deaths, inspired by influential thinkers and books, such as “Being Mortal,” by the Boston surgeon Atul Gawande. These patients want end-of-life care designed to help them live their last days better; that sometimes means turning down aggressive treatments that might extend life by weeks or months at the potential cost of whatever vitality they have left.

In 2000, about 45 percent of all Massachusetts deaths were in hospitals. That number has ticked down, slowly but consistently; in 2019, 36 percent of Massachusetts deaths were in a hospital.

But like so much else related to death, the trend is complicated along racial lines.

Black people are far less likely than white people to complete an advanced directive, a document that spells out to doctors and EMTs what kind of end-of-life care a person wants for themselves, often with an eye toward avoiding aggressive treatment unlikely to do much good. Sixty-five percent of white people age 65 or older have documented their treatment preferences, compared to just 19 percent of Black people and 48 percent of Latino people, according to a 2017 Kaiser Family Foundation survey.

Black patients are also getting less hospice care. About 2.2 million Medicare recipients died during the 2015 calendar year. About 51 percent of white patients who died received some hospice services, but only 38 percent of Black people did so, according to a University of Southern California analysis.

Hospital deaths also show a sharp racial split, supporting the idea that Black patients are more likely to pursue aggressive treatment longer or may sometimes have fewer support systems to die at home or in residential-like settings. In 2019, about 46 percent of all Black residents who died in Massachusetts died at a hospital, while only 35 percent of white deaths were in a hospital.

Racial differences are even more dramatic in one of the most polarizing end-of-life issues of our time, the right of terminally ill patients to seek prescriptions for lethal drugs to end their own lives, called, among other things, medical aid in dying. In states that permit the practice, including Oregon, Washington, and California, the participants have been overwhelmingly white, far whiter than the racial makeup of those states. Massachusetts in 2012 narrowly defeated a medical aid in dying referendum; the Globe/Suffolk poll suggests voters have potentially changed on the issue, with about 70 percent now in favor of legalizing it.

The Rev. Gloria White-Hammond, a physician and the co-pastor of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Boston, said that many Black patients are more concerned about not getting enough treatment, due to racism, than having a bad death due to too much unnecessary care.

These patients and their families are more likely to resist if a doctor recommends switching from aggressive curative treatments to comfort care, she said. Part of that mistrust comes from past outrages, such as the notorious Tuskegee Study, in which doctors experimented on Black men by secretly withholding treatment for syphilis while pretending to care for them.

For some, the pastor said, faith can also affect the cost-benefit calculation of treatment, sometimes frustrating well-meaning doctors.

“These physicians get so honestly annoyed with these Black Christian people who are believing [in] God for a miracle, and we (doctors) want to turn off all of this stuff because it’s not helping,” she said. “We think the patient is suffering and they won’t let us turn it off.‘'

For many older Black patients, there is the additional wariness that comes from the legacy of having been unable to get care at “white” hospitals in their youth.

Waters and Bessie Burroughs remember those days. The transplanted Southerners, married 58 years, are gracefully aging through their early 80s, on a tidy street in Springfield. Bessie has survived several bouts of cancer. It has shaped how she thinks of death.

When the time comes, she’d prefer to die quickly. She doesn’t want to be a burden on anyone, unable to care for herself. She is not keen on dying at home but doesn’t want a highly medicalized death connected to machines. She believes that many Black patients who seek aggressive care just haven’t engaged yet in these kinds of detailed conversations about the end-of-life care they might want.

Bessie was born at home in Aliceville, Ala., in 1938. As a girl, she sat with her mother in the “colored” waiting room at the doctor’s office, separate from the white patients. All waiting to see the same white doctor. Under those circumstances, she said, how could Black families not have gotten inferior care?

“You could not sit in the waiting room, but yet this same doctor is supposed to be pretending that he’s doing for you like he’s doing for the others?” she said. “Think about that.”

The Burroughs believe race still does have some effect on care but is not the most important factor any more; unequal care can be divided these days along other lines. Some hospitals and medical practices cater more to the wealthy, while others serve largely low-income patients on Medicaid.

“It’s money now,” Waters said. “Money talks.”

Mark Arsenault can be reached at [email protected]. Any tips and comments can also be sent to the Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected] or by calling 617-929-7483.

The entire Last Words series can be found at www.bostonglobe.com/lastwords.

How we reported this series

Determining income categories: Identifying what income level is "middle class" is challenging, especially as cost of living differs widely across the country. The Globe chose to use a Pew Research Center definition of middle class, which ranges from two-thirds to double the median household income for an area. For our Massachusetts deaths, the Globe used the US census calculations for median household income for this state.

Beyond that, our analysis then established a spectrum of income levels, ranging from "very low" (defined as up to 125 percent of the federal poverty guidelines for a family of four) to "high" income (defined as at least double the median household income). Also middle class is often divided into "middle-low" and "middle-high" along the half-way point of that income span, and "low" is simply between "very low" and "middle-low."

Estimating a deceased person's income level: The income level of people who have died is not available on death certificates or generally publicly available. The Globe - as well as other demographic researchers - have used as a proxy the median household income of their home address' census tract or zip code. Globe reporters ran the data both ways, and the results were similar. In most cases, the data reported in the stories relies on income figures from census tracts; however in some charts on the data page, zip codes were used.

The deaths included in the Globe analysis: All Massachusetts deaths from 1999 through the middle of 2020, except for those with out-of-state home addresses.

Data on where people died: Numbers do not add up to 100 percent due to rounding and because some charts do not contain every category, such as "other" locations where people died.

Some caveats in interpreting the median age of data: The Globe was cautious in interpreting trends in median age of death, especially around race and ethnic background. This can be heavily influenced by immigration patterns and sizes and age distributions of the different populations. Median age of death means half the people who died were older than that median age, and half were younger. It should not be confused with life expectancy, which estimates the lifespan of people living today.