Miami team

Nov. 2, 2022

‘Selma has given so much to the world’: Residents on what’s changed — and what’s left to be done

SELMA, Ala. — Charles Bonner is standing outside Carter Drug Co., the downtown pharmacy where, on this day 59 years ago, he and some high school friends sat at the lunch counter to protest segregation.

On that afternoon — Sept. 16, 1963 — one of the group, Willie C. Robinson, was struck in the head by the store owner and others, including Bonner, were arrested. Bonner has returned today to mark the anniversary, but also to pay tribute to the woman who helped spur the drugstore sit-in and other Selma protests, including 1965′s “Bloody Sunday,” when hundreds of marchers were brutally attacked by state troopers as they walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

In the early 1960s, Colia Lafayette Clark and her husband, Bernard Lafayette Jr., were field directors with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. At their home in Selma, the couple spent countless hours with Bonner and other young people, teaching them about nonviolence and the power of peaceful protest.

It’s wisdom that changed Bonner’s life. Now 76, he’s a civil rights attorney in San Francisco, with clients that include families affected by the recent Uvalde, Texas, school shooting and the massacre at a supermarket in Buffalo. He returns to Selma two or three times a year, and he’s discouraged by what he sees: blocks of burned or boarded-up buildings, desperate poverty, and rampant violence.

“When I was growing up in Selma, there were no Black cops, no Black legislators, no Black anything in power. In 2022, there are,” he said. “But economically, the town is withering.”

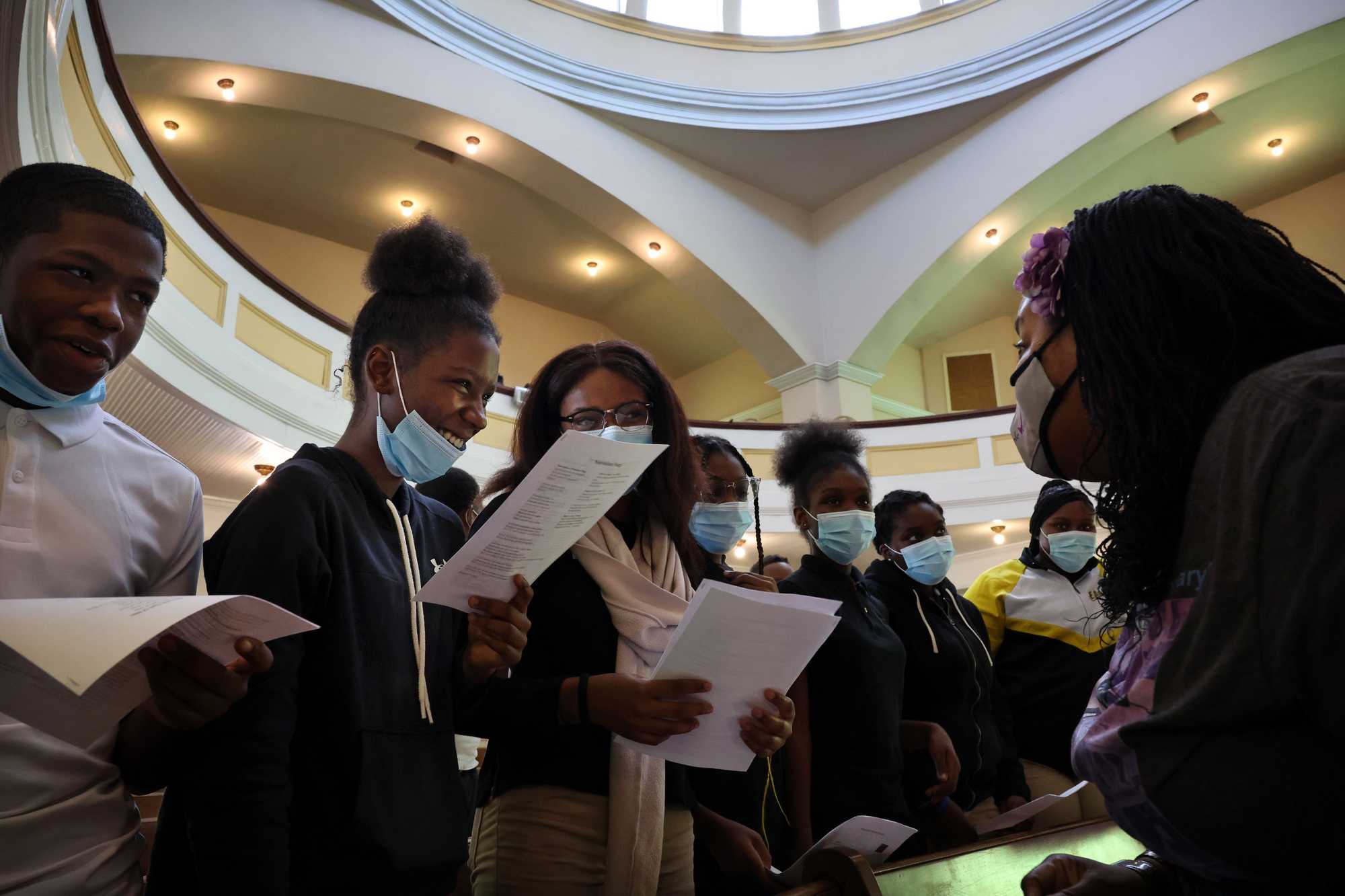

Lafayette Clark, now in her early 80s, lives in Harlem and was unable to attend the events held in her honor. But over the course of Colia Lafayette Nonviolent Freedom Day — which included a march to Carter Drug Co., nonviolence training for high school students, and a banquet — we spoke to residents, activists, students, and city officials about what’s been accomplished here, and what’s left to do.

Charles Bonner, civil rights attorney: “The born free — those who were born after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act — don’t have the same viewpoint. They don’t have that fire, the ability to keep fighting to keep plugging up the holes in the ship. As I tell folks, we were brought here packed like sardines in ships. We’re still in a ship, not only Black people, but all of us on this planet. We’re all in a ship and it’s got [a] hole in it.”

Sam Walker, lifelong Selma resident: “When integration happened, it hurt Black folk, and some of that was self-inflicted. The idea of integration was for Black people to go off to cities or other areas and get new opportunities, opportunities that had been denied to them in the past. But the goal was, once you capitalize on those opportunities, bring them back to your community and share them with other folks who didn’t leave. We didn’t do that. We went off and stayed in their community. Nobody made us do that. We could have come back. My friend’s father used to say, ‘No generation can expect to see the end of struggle, but each generation has a responsibility to advance the struggle.’ I tell young people just do your part in advancing the struggle.”

Henry Edward Allen, Selma’s first African-American firefighter and fire chief: “People used to be closer together. You had very little and you shared what you had. There were no locks on the door. Everybody looked out for everybody. Where we are right now is an economic factor. The houses that I grew up in, they fall into the ground, grass has taken over. Selma’s the third-oldest city in the state of Alabama, so our infrastructure is terrible. What we really need is a blank check from Capitol Hill. People are moving out, they ain’t moving in.”

Ainka Jackson, executive director, Selma Center for Nonviolence, Truth, and Reconciliation: “There’s an intense level of physical violence in Selma, for a variety of reasons, but we’re never taught how to resolve conflict. I tell kids: Conflict is inevitable, but combat is optional. The training I do teaches these kids how to build and grow relationships when there’s conflict. All over the world, Selma is looked to in terms of our history, but in 2019, we were the ninth poorest town in the country; murders went up by 56 percent last year. Selma has given so much to the world and the world really has to give back to Selma, not just come and take a picture at the bridge and leave. Really invest in Selma. Spend the night here, buy food and gas here, go to the museums here. That investment in Selma will pay off for these young people.”

Faya Touré, civil rights activist, lawyer, and founder of the National Voting Rights Museum and the Selma Bridge Crossing Jubilee: “You live in Selma, which is 83 percent [Black residents], with an all-Black school board and a Black superintendent, and there is not one course — not even any elective course — in Black history. There’s not an elective course on civil rights history. After the victories of the Civil Rights Act and the right to vote, we never had a movement to end the miseducation of Black people — to explain how white supremacy will keep us in mental chains. I call it the new noose. The noose is around our minds, not around our necks.”

LaTonya Mitchell, Selma resident and owner of Vinyl Express, the shop that made the Colia Lafayette Clark T-shirts: “I think people in Selma are so close to it that they don’t know the history. They walk right over it. They just wake up and live it. So, no, they don’t know the history. Like, I didn’t know about Colia [Lafayette Clark] until I started making the T-shirts. So I was introduced through a job! Throughout this day, I hope something that’s been said about her at these nonviolence workshops for the children, I really hope they get something out of it, that it will open up their eyes and they say, ‘Hey, these people fought for me. Let’s let’s stop killing one another, let’s stop fighting.’”

Ayiraa Fortier, 14, student at Ellwood Christian Academy: “A lot of the people around here have normalized violence when it shouldn’t be normalized. They just kind of feel like it’s bad, but it happens so often, it’s just something you’re used to. And I feel like we should not get used to it. This is really, really bad. People are getting murdered. I just can’t understand why people want to hurt anybody else. You don’t know who their family is. You don’t know how that’s gonna make their mom or their dad feel. I feel like, at this point, people have so much built-up pain and hurt. They don’t care what happens anymore. Peace. That’s something we really need around here.”

Interviews have been edited and condensed.

Join the discussion: Comment on this story.

Credits

- Reporters: Julian Benbow, Diti Kohli, Hanna Krueger, Emma Platoff, Annalisa Quinn, Jenna Russell, Mark Shanahan, Lissandra Villa Huerta

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Pat Greenhouse, Jessica Rinaldi, and Craig F. Walker

- Editor: Francis Storrs

- Managing editor: Stacey Myers

- Photo editors: William Greene and Leanne Burden Seidel

- Video editor: Anush Elbakyan

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: John Hancock

- Copy editors: Carrie Simonelli, Michael Bailey, Marie Piard, and Ashlee Korlach

- Homepage strategy: Leah Becerra

- Audience engagement: Lauren Booker, Heather Ciras, Sadie Layher, Maddie Mortell, and Devin Smith

- Newsletter: LaDonna LaGuerre

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Additional research: Chelsea Henderson and Jeremiah Manion

© 2022 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC