Miami team

Oct. 27, 2022

A mother’s loss after the Oklahoma City bombing is seared in a photo we can’t forget

OKLAHOMA CITY — You might remember the photo. I can’t forget it.

All these years later, that image of the child, bloodied and lifeless, being cradled by a firefighter in the frantic aftermath of the Oklahoma City bombing still makes me shudder.

I was 29, about to get married and contemplating having kids, when an anti-government, pro-gun zealot parked a Ryder moving truck packed with explosives outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building and walked away.

What happened on the morning of April 19, 1995, remains the deadliest act of domestic terrorism in US history, a shocking fact considering how much home-grown savagery we’ve endured since. The front of the nine-story building was sheared off in the blast, killing more than 100 people instantly. It took rescue crews more than two weeks to sift through the rubble, by which time the death toll had reached 168, including 19 children.

No picture captured the unconscionable tragedy of that day more than the photo of the baby, her slack limbs dangling over the arm of the firefighter. Taken by amateur photographer Charles Porter IV — he developed it at a nearby Walmart — the photo was published and broadcast around the world and won a Pulitzer Prize.

Its effect on me was intense. I’d been ambivalent about having kids, and the atrocity in Oklahoma City, symbolized by this one awful image, made me wonder if a world capable of such barbarism is a world I’d want to raise a child in. The picture resurfaces from time to time — usually on the anniversary of the bombing — and I always think about the baby’s parents. What effect has it had on them?

Now I know.

Recent stories from the Miami team

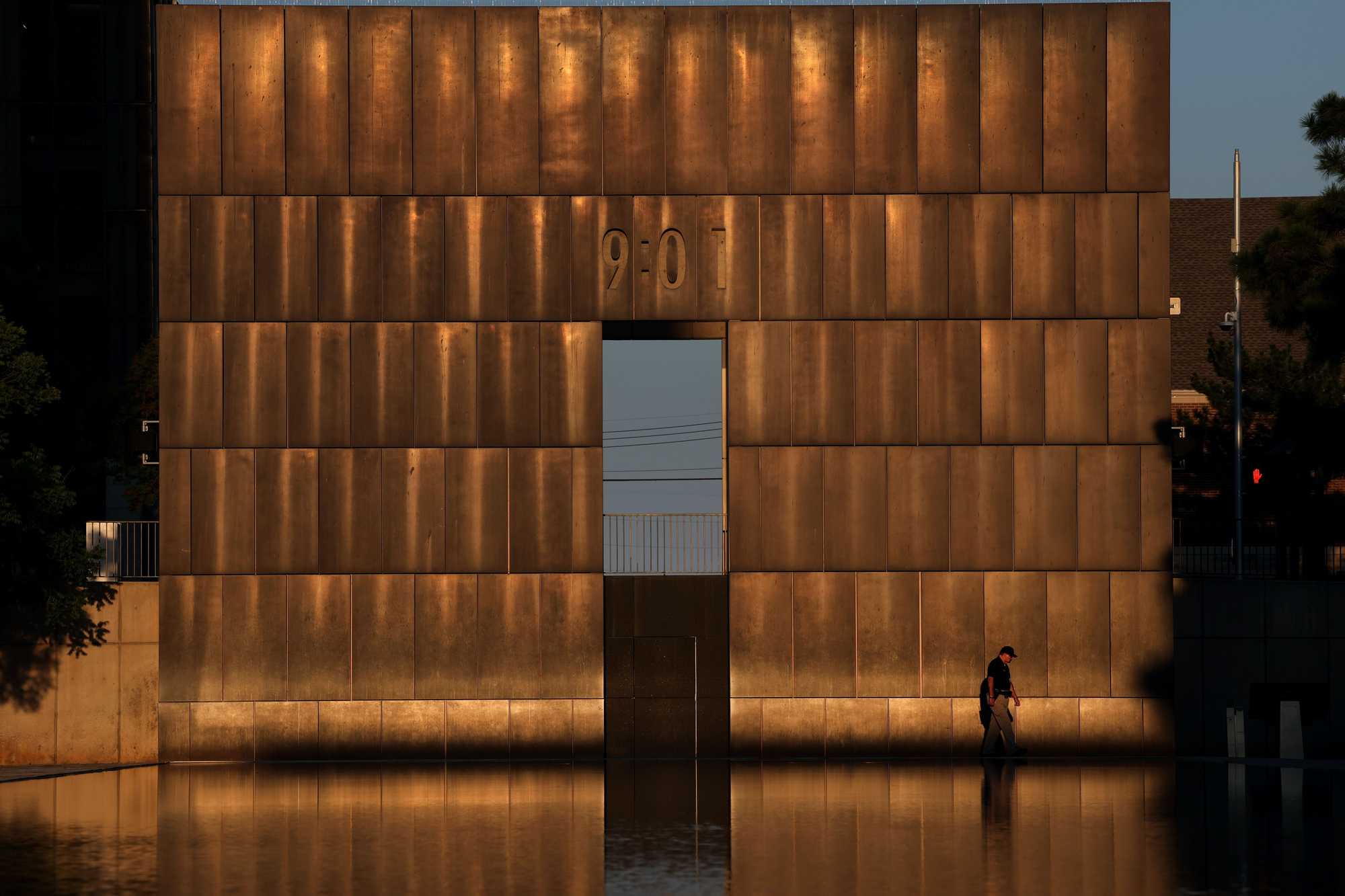

Aren Almon was a 22-year-old single mom in 1995. She and her infant daughter, Baylee, lived in a high-rise a block from the Murrah Building. Almon lives there today, but now her apartment overlooks the Oklahoma City National Memorial, a tranquil space the size of a city block with a reflecting pool and several tall evergreens that stand sentry over a manicured lawn with 168 empty chairs.

“I don’t look at the memorial and feel like Baylee’s there,” Almon told me. “She’s wherever I want her to be. She’s wherever I am.” After the bombing, Almon moved away and married, but came back after getting divorced. “I know it freaks people out that I live here. But it doesn’t bother me. It doesn’t make me feel better, either. Nothing’s going to do that.”

On the morning of April 19th, the day after Baylee’s first birthday, Almon dropped her daughter off at the day-care center in the Murrah Building and continued on to her job at an insurance agency 10 blocks away. Not long after, she felt the earth shake. Looking out the window, she saw a thick spiral of black smoke rising over downtown.

The story Almon tells about the next 12 hours is excruciating: the ghastly scene amid the debris of the federal building; her frenzied search for any sign of her daughter; the sprint between hospitals; and, finally, the news that Baylee was dead.

“The pediatrician walked around the corner with a priest,” Almon recalled, starting to cry. “And I knew she was gone.”

What followed was a blur. Almon, who’d never experienced loss, was despondent. Overwhelmed. Then she saw the photo. The day after the bombing, The Oklahoman, the state’s largest newspaper, put Porter’s picture of Baylee on the front page, and Almon, already in shock, was inconsolable. Within days, the image was everywhere.

“I literally had to stand in grocery stores and see my daughter’s dead body on the front of magazines,” she said. “People sold T-shirts with it. I mean, I get that it was a symbol of the innocence lost, but for me, it was a child — my child.”

The ubiquity of the image caused pain for Almon in unexpected ways. It made her a frequent focus of news stories about the bombing, which meant she was recognized by strangers, many of whom felt no compunction about approaching her on the street and saying stupid, insensitive things. Three years after the bombing, when she was pregnant with her second child, Bella, Almon was told, more than once: “You know, you can’t replace Baylee.”

“But the worst is when they come up to me crying and I have to comfort them for my loss,” said Almon, who also has a 21-year-old son, Broox.

The photo sowed resentment. Other families who lost loved ones in the bombing felt overshadowed or ignored, and they blamed Almon. “They think Baylee’s never going to be forgotten and their kids are,” she said. “They act like I took the picture and put it out there.”

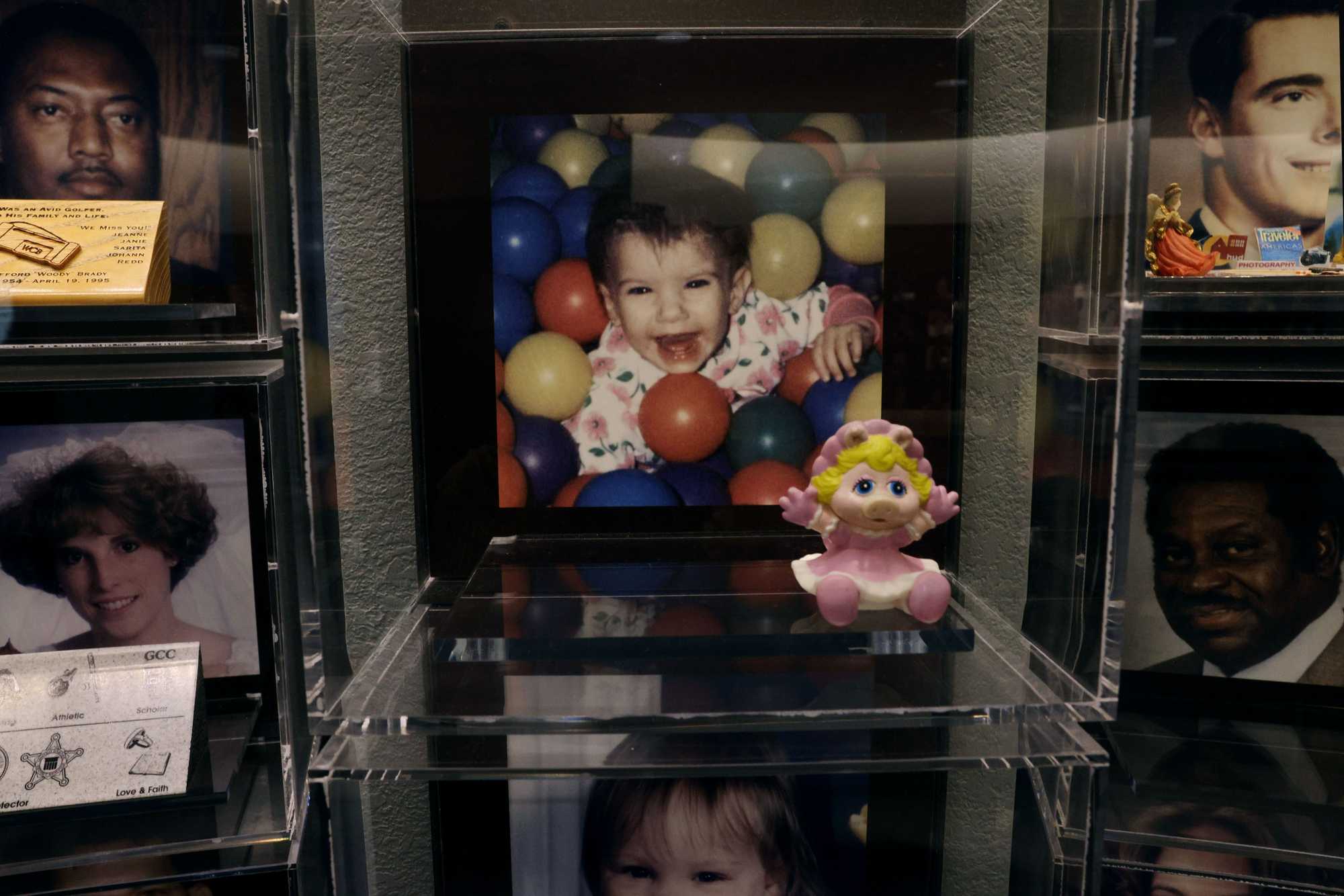

It was baking hot as I walked around the memorial with Almon and Bella, now 24. But it was also lovely in its way — quiet and peaceful. As we stood beside Baylee’s memorial chair, which Almon decorates on every holiday, a mother and daughter visiting from Indiana wandered up. Like so many others, they’d seen the famous photo and wanted to pay their respects.

They were dumbstruck to discover that the women there were Baylee’s mother and sister. The four chatted briefly and then Christine Russell and her daughter, Anna, continued walking, heads bowed.

“She’s paid a huge price because of that photo,” Russell said softly.

It’s true. Almon is still stricken by the sight of the picture. And yet, she also knows it tells the story of that horrific day in a way that words can’t. Resting her hand on the back of Baylee’s empty chair, Almon gets tearful again.

“I know where she is, and I know she’s safe,” she said, “but I miss her so much.”

With Bella at her side, Almon turned to go. But I lingered. My wife and I did have children — a girl and a boy. They’re 21 and 18 now. Beautiful people. The world may not be any less cruel, but there’s a little more love in it.

Join the discussion: Comment on this story.

Credits

- Reporters: Julian Benbow, Diti Kohli, Hanna Krueger, Emma Platoff, Annalisa Quinn, Jenna Russell, Mark Shanahan, Lissandra Villa Huerta

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Pat Greenhouse, Jessica Rinaldi, and Craig F. Walker

- Editor: Francis Storrs

- Managing editor: Stacey Myers

- Photo editors: William Greene and Leanne Burden Seidel

- Video editor: Anush Elbakyan

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: John Hancock

- Copy editors: Carrie Simonelli, Michael Bailey, Marie Piard, and Ashlee Korlach

- Homepage strategy: Leah Becerra

- Audience engagement: Lauren Booker, Heather Ciras, Sadie Layher, Maddie Mortell, and Devin Smith

- Newsletter: LaDonna LaGuerre

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Additional research: Chelsea Henderson and Jeremiah Manion

© 2022 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC