Boston team

Nov. 2, 2022

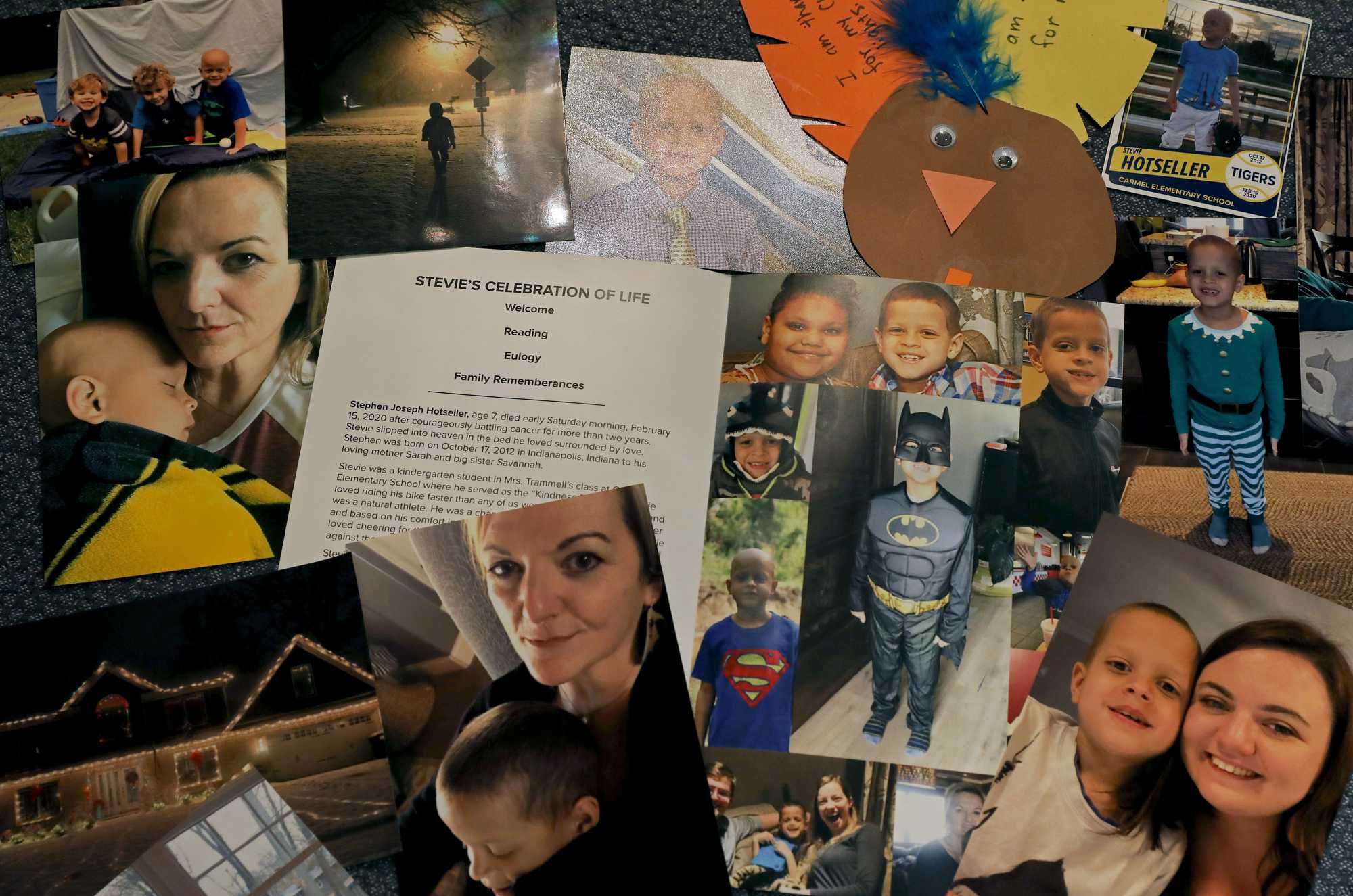

She has fostered 79 children. One of them was named Stevie.

CARMEL, Ind. — Allie Missler never wanted a third child, until Stevie.

By the time she volunteered her home for emergency short-term foster care in 2017, she and her husband had already raised two kids in their suburban four-bedroom. All they hoped to do was provide temporary shelter for children in central Indiana who needed help: A malnourished 1-year-old who only weighed 11 pounds. A spunky preteen (and her doll, Malachi). Three infants who were surrendered at “safe haven” locations, where no questions are asked.

In total, the couple has housed 79 kids for anywhere from one night to several months.

Many children arrived in the middle of the night, because the alternative was sleeping at the offices of the state Department of Child Services. “I insisted that no child will sleep on the floor of the office,” Missler said. She told DCS staff: “You call me for every child.”

She had no intention of adopting. But somewhere along the way, Stevie changed her mind.

He arrived in Carmel at age 5 with a ruptured kidney tumor that had spread cancer through his body. The Misslers opened his eyes to what felt like a life of luxury where the pantry was always stocked, and strawberry was a fruit, rather than just a flavor.

“Jesus Christ,” Stevie said on his first day in the Missler home. “How many people live here?”

Stevie swore like a sailor. He also loved Batman, Nerf battles, and “Home Alone.” Quickly, he began to call Missler “Mama.”

For much of 2018 and 2019, the couple brought Stevie to chemotherapy and scheduled visits with his birth mother — a kind twentysomething woman from Indianapolis who did not have enough to support a second child, let alone one with cancer. She had no money, no car, not even someone who could drive her and Stevie to doctor’s appointments. “Everyone wants her to pull herself up by her bootstraps,” Missler said. “But I’m screaming because she has no shoes.”

Around the time that Stevie went into remission, his mother asked the Misslers to adopt him. They agreed. He started kindergarten at Carmel Elementary School and began learning to read at a lightning pace. Tufts of ginger hair began to grow back on his head.

Then his cancer rebounded and moved to his lungs.

On Feb. 15, 2020, he died.

It was quick and peaceful, sometime around 2 a.m. All the visitors had left for the day, and Missler and Stevie were listening to Yo-Yo Ma play Bach’s Cello Suites. They had just finished reading “Goodnight Moon.”

“I saw wonder in his eyes,” Missler said. “Not a drop of fear.”

A wave of grief set the Missler family aflame. They erected “Stevie’s Garden” in the backyard with herbs, tomatillos, kale, and tulips they donate to the Carmel United Methodist Church. Meredith, the oldest Missler child, got a tattoo on her left forearm — a rendering of sound waves of Stevie saying “I love you, Mer Mer,” his nickname for her.

To spread his ashes, the Misslers traveled everywhere Stevie one day hoped to go: Central Park in New York City, a picturesque beach in Turks and Caicos, a glacier in Norway.

“This way he’s everywhere,” Missler said.

Often, Missler can’t help but think that Stevie would have lived if he had been born under different circumstances, if his mother had been able to give him the medical care he desperately needed earlier. “His cancer had a 98 percent cure rate, if his mother had access to transportation,” she said. “Let’s be real clear: Stevie died of poverty.”

His death should be a rallying call, she said, to fix the cracks in a foster care system so broken that children often arrive overmedicated “with a Ziploc baggie of loose pills” and zero documentation to confirm their allergies, background, or even their last name. It’s a reminder that there are so many more kids trapped in the same maze of bureaucracy — and few adults to help them. In Indiana, only 6,200 parents are licensed to care for the 13,000 children currently in the system.

Recent stories from the Boston team

“They are all as important as Stevie,” Missler said.

She’s taken her grievances to the state Capitol and challenged lawmakers to fund policies that support the “family first” motto many love to tout until it comes time to apportion funds. Parents need more than $21 per day to care for a foster child, and DCS could do wonders with more money, Missler said. “Love is not all you need,” she added. “Cash helps.”

For now, the Missler family is taking Stevie’s loss day by day — or better yet, child by child. Foster children still file through their door regularly for a warm bed and a hand to hold. Some are newborns already hooked on opioids; others are high schoolers, looking for guidance as they embark on a parentless adulthood.

For these parents, reminders of their third child linger. Though Missler repainted Stevie’s blue room back to beige and donated his clothes, she refuses to paint the upstairs baseboards scratched by Stevie’s remote control car. Underneath the dining table, his secret stash of Nerf darts sits untouched.

Once in a while, Missler does a double take to see a neighborhood kid stuffing rocks in her mailbox, wearing Stevie’s old shirt.

“Sometimes I look up and think, ‘Oh, that’s my boy.’”

Join the discussion: Comment on this story.

Credits

- Reporters: Julian Benbow, Diti Kohli, Hanna Krueger, Emma Platoff, Annalisa Quinn, Jenna Russell, Mark Shanahan, Lissandra Villa Huerta

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Pat Greenhouse, Jessica Rinaldi, and Craig F. Walker

- Editor: Francis Storrs

- Managing editor: Stacey Myers

- Photo editors: William Greene and Leanne Burden Seidel

- Video editor: Anush Elbakyan

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: John Hancock

- Copy editors: Carrie Simonelli, Michael Bailey, Marie Piard, and Ashlee Korlach

- Homepage strategy: Leah Becerra

- Audience engagement: Lauren Booker, Heather Ciras, Sadie Layher, Maddie Mortell, and Devin Smith

- Newsletter: LaDonna LaGuerre

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Additional research: Chelsea Henderson and Jeremiah Manion

© 2022 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC