MACON, Ga. — Desperate to hold on to power, Donald Trump gripped the lectern bearing the presidential seal and prepared to deliver another election lie.

He had helicoptered to Dalton, Ga., to hold a rally for Republican candidates on the eve of the state’s Jan. 5, 2021, Senate runoff election. But Trump spent much of his nearly 90-minute speech spreading false allegations about fraud in the presidential election he had lost two months earlier.

“Anybody live in Bibb County?” he asked the crowd. “Bibb. Bibb. Bibb. B-I-B-B.”

He asserted that more than 12,000 votes had been switched there from him to Joe Biden on Election Night. “It was like a miracle!” Trump bellowed, stretching his arms sarcastically after the rallygoers booed.

It also was completely untrue.

Trump devoted less than a minute of his screed to that particular allegation, but it was enough to unleash a cascade of problems roughly three hours to the south in Macon-Bibb County. Threats and intimidation. The elections supervisor’s resignation. A controversial search for a permanent replacement that ended up in court.

The job remains unfilled just days before the November midterms, putting an interim elections supervisor in charge at a time when there’s more pressure on the system and the people who run it than ever before.

The tumultuous 2020 presidential election and its misinformation-filled aftermath overwhelmed many local elections supervisors. They’ve quit in droves around the country, chased away by harassment, burnout, stress, a blizzard of time-consuming public records requests from election deniers, and, in multiple states, new election rules that made the already difficult and often thankless job too much to handle.

The turnover has been dramatic in the tightly contested states that decided the presidential election two years ago: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

A Globe analysis of those states, along with Massachusetts, found that about 30 percent of top local election officials have left their jobs since 2020. That was a significant increase compared to the 18 percent turnover in the two years after the 2016 presidential election. In Georgia, at least 57 of the state’s 159 county elections supervisors — about 36 percent — have left since 2020. That’s up from the roughly 21 percent who left the jobs after the 2016 presidential election.

It’s not surprising. Georgia arguably has been the eye of the political storm in the aftermath of the 2020 election. The state has been rocked by controversy after controversy, and may, once again this year, prove to be pivotal in deciding which party will control the US Senate.

Nowhere, in other words, is there a greater need for an experienced, nonpartisan corps of local elections officials. And in Georgia, that corps has been severely depleted as early voting has already begun ahead of another crucial Election Day on Nov. 8.

President Biden won the state by just 11,779 votes, an upset that drew the wrath of Trump and his supporters. A barrage of unproven fraud allegations followed and spurred death threats against elections officials, an ongoing criminal investigation into potential election interference in Georgia by Trump’s allies, and a new more restrictive state election law that has triggered protests and boycotts.

After helping swing the 2020 presidential election to Biden, the state held a Senate runoff election in early 2021 that delivered narrow control of the chamber to the Democrats. Georgia will be in the spotlight again on Nov. 8, when its closely contested Senate race once more could be a majority-maker — and possibly force election workers here to go into overtime again with a Dec. 6 runoff if neither candidate tops 50 percent as required by state law.

“It’s like the world’s watching Georgia,” said Deidre Holden, the elections supervisor in Paulding County and the former co-president of the Georgia Association of Voter Registration and Election Officials. “Some people can’t take that pressure. They don’t want to be put under a microscope. They don’t want their every little move to be questioned.”

Macon-Bibb County’s longtime elections supervisor, Jeanetta Watson, joined the exodus this past January. She stepped down after nearly a decade in the position, citing the “overwhelmingly stressful” demands of a job that since 2020 has involved “rapidly changing election laws, policies, and procedures” that have “taken a toll on my mental health.”

“Election officials throughout the state share these same sentiments and have also decided to resign, retire, and or pursue other careers,” she wrote in her resignation letter.

Finding permanent replacements for these critical workers in this environment has not been easy.

“People read what’s happening,” said Mike Kaplan, the chair of the Macon-Bibb County Board of Elections. “We don’t have a lot of people dying to become an elections supervisor, and it’s not just here. It’s everywhere.”

Advertisement

Macon-Bibb County’s elections are run out of a former Shoe Carnival outlet in Macon, across the street from a pawn shop and a Krispy Kreme store. Since she departed, Watson’s former office there has morphed into a temporary storage room.

One day last month, multicolored binders were clustered on a corner of the L shaped, dark wood desk. A quartet of white bankers boxes were on a folding table set up in the middle of the room. And standing sentinel inside the door was a silver metal absentee ballot drop box that the county no longer can deploy because of the new state law restricting its use.

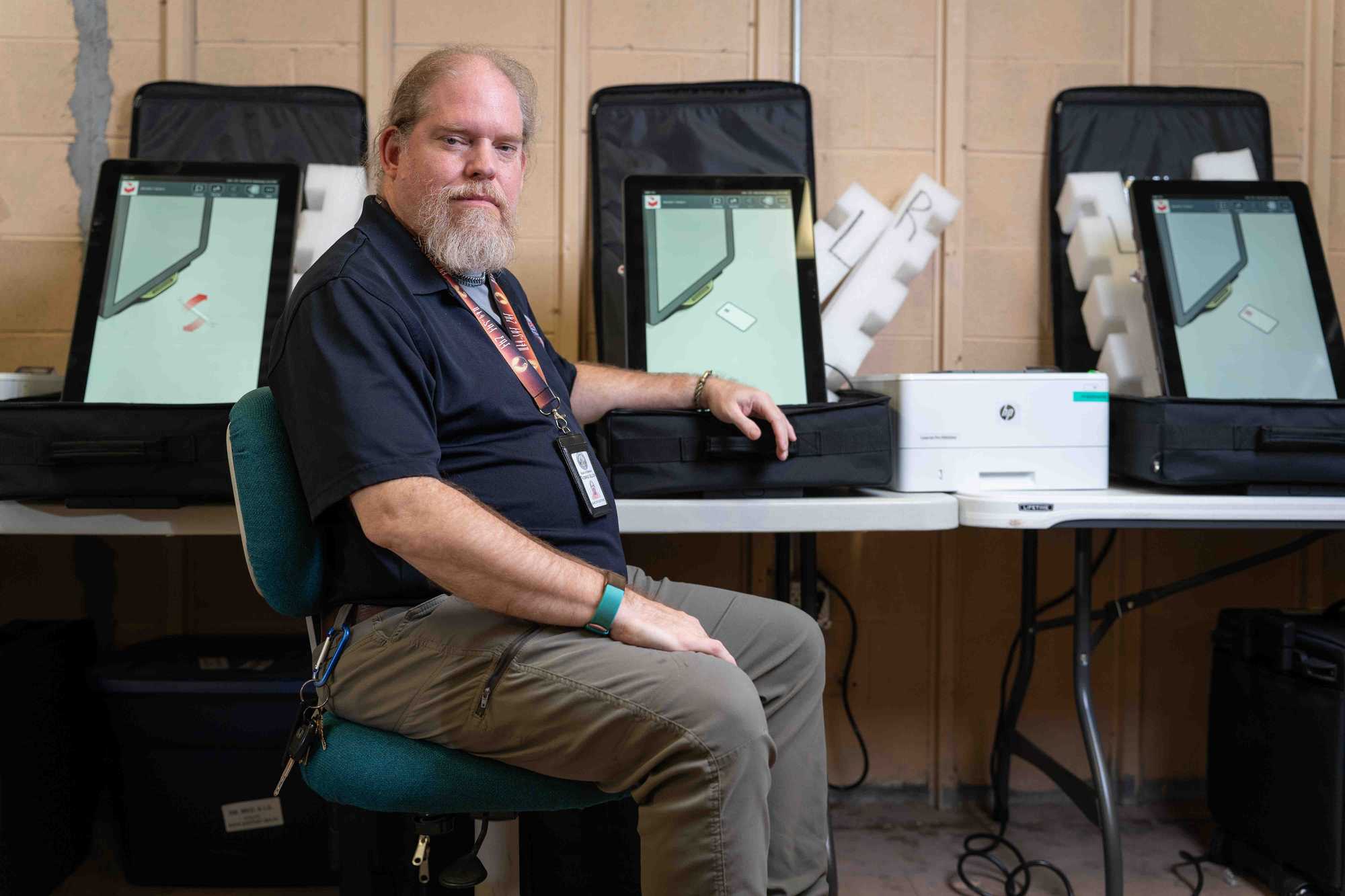

The county’s interim elections supervisor, Thomas Gillon, walks past the vacant office when he arrives each morning a little after 8 a.m. He prefers the smaller, windowless space just down the hallway where he has worked since 2013 as the county’s election officer, a catchall position that includes responsibility for poll workers, candidate campaign filings, and even jumping in to run a polling place on Election Day if needed.

This year, he’s had to jump in to run the entire elections operation in this county of about 157,000 residents roughly 90 miles south of Atlanta — all while still performing his old responsibilities.

“It’s certainly not a stress-free job,” said Gillon, 52, a lifelong Macon resident with a graying beard, ponytail, and a penchant for understatement. As he sat at his desk under the low hum of the HVAC system one September morning, Gillon explained that he received valuable experience this spring after running the county’s primary elections. Aside from one minor problem — a misspelled candidate’s name on the ballot — he said his first time running the whole process in this hyper-sensitive environment went well.

“Phew, you survived with no lawsuits, nobody coming up with pitchforks and flaming torches or anything like that,” Gillon said, describing his feelings once the primary was over. “If we did that one, we can do another one.”

Hundreds of local officials across the country are in the same position. They’re running elections for the first time this year after departures that have drained expertise and experience from the nation’s highly decentralized system of election management just as it faces intense new scrutiny because of the continued lies of Trump and his supporters.

“It’s the institutional knowledge that walks out the door that you can’t really replace for years,” said Richard Barron, who stepped down late last year as the elections supervisor in Fulton County, the most populous in the state. He and his staff faced death threats after Trump and his supporters focused much of their anger about his Georgia loss on the county, which is home to Atlanta.

“If experienced election officials across this country continue to quit or are run out of their jobs because of this ridiculous harassment, who’s going to take their place? The answer: It’s inexperienced people,” Lisa Marra, the elections director in Cochise County, Ariz., warned at a roundtable in August on election misinformation held by the US House Oversight and Reform Committee. “And that’s not going to help us move the needle to increase voter confidence in America.”

The inexperience takes different forms: people who’ve never worked in the field but were drawn even in this environment to perform a crucial role for democracy; those with experience but from a job in another state with different election laws and procedures; and local election workers who’ve been elevated to the top position for the first time either permanently or temporarily because of a struggle to fill vacancies. Fulton County, for example, has not been able to find a permanent elections supervisor for nearly a year.

Hear from election workers

The Globe interviewed dozens of current and recently departed election officials. Here’s what they had to say about what it’s like to run elections in the wake of 2020.

For those who have taken on these now high-profile jobs, the learning curve is steep, the margin for error razor-thin.

Even veteran elections supervisors said it’s difficult to run a flawless election with myriad moving parts that often go wrong in the casting and counting of thousands and sometimes millions of ballots. In the past, minor problems that didn’t alter the outcome of a race drew little attention.

No more.

Election officials worry about rookie mistakes causing more of the kinds of problems that deniers have seized on. After the 2020 election and the mistrust caused by Trump’s lies, every glitch can be amplified, every mistake blown out of proportion and trumpeted as evidence of a partisan conspiracy — a conspiracy bereft of evidence. That leads to the departure of more stressed and frustrated elections supervisors and the hiring of less-experienced ones who are more likely to slip up.

It all creates a vicious cycle at a time when American democracy can least afford it.

Advertisement

It seems difficult to get Stacey Godfrey down.

She has an upbeat personality and an easy laugh. With Halloween approaching, her office in the small town of Jasper, Ga., was decorated with little silver and gold pumpkins along with festive wooden signs declaring “Autumn blessings” and “Welcome Fall.”

But she admitted there have been times that the hassles of her new job as the Pickens County elections supervisor — the first time she’s ever worked in the field — have gotten to her.

“I won’t say that there have not been days that I haven’t been like, ‘What was I thinking?’ " said Godfrey, sitting behind her desk wearing a black shirt with the county’s green and blue seal and a lanyard holding an oval “Secure the Vote” button. But her laugh returns when she later adds, “I will proudly say I’ve been in this job for a year and I’m not on medication!”

Pickens County has about 34,000 residents and bills itself as the “Gateway to the North Georgia Mountains.” It’s a strongly Republican area that gave 82 percent of its 2020 presidential vote to Trump. Godfrey has lived there her whole life and when the elections supervisor job became vacant in early 2021, she decided to apply.

She had been working for the county for three years in planning and development and believed the elections post was a particularly important job. She also thought it would be good to have more women in supervisor positions. But she didn’t think she’d be chosen.

“I had never even been a poll worker,” she said.

But Godfrey was the county’s pick out of five candidates. She took over in July 2021 and immediately learned there was no playbook for the job.

“We were pretty much walking through everything blind and just trying to feel our way,” she said. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had to pick up the phone and call my counterparts in other counties because I don’t know the answers to things.”

One of the people she leaned on was Holden, the elections supervisor in nearby Paulding County since 2007. Holden tries to mentor the new elections supervisors in her region — and there have been more of them around the state since 2020.

“When I first got into elections and I would go to our conferences, you knew you were going to see the same faces every year because this is something you do for a long time,” Holden said. “Now, you get to a conference and you don’t recognize anybody. I’ve been doing this for all these years and it’s like, ‘Where are all these new people coming from?’ ”

Although states provide training, election officials have banded together to help new colleagues learn the job because everyone’s reputation now is on the line.

“If a county messes up,” Holden said, “we’re all at fault.”

Godfrey acknowledges there was a lot she didn’t know when she took the job in Pickens County — including one detail that blew up on her this spring.

She had gotten her feet wet with a small municipal election in November 2021, but things got more complicated this May with a primary for Congress and state offices, as well as local races and ballot questions. Each ballot was 18-inches long, with choices on the front and back. Because it was her first big election, Godfrey said she focused on making sure every candidate was properly listed.

She didn’t realize that Georgia law requires the candidates be listed in alphabetical order.

Godfrey had listed the local race candidates in the order that they qualified for the ballot. She was fortunate that in nearly every race, they happened to qualify in alphabetical order. But that wasn’t the case in the most controversial contest, the battle for a county Board of Commissioners seat. Somebody discovered those candidates were not in proper order. Godfrey said she was horrified when she found out and immediately notified the state, but early voting had already started so there was no way to fix the ballots.

In the super-charged post-2020 environment, word of the incident “spread like wildfire” on Facebook, she said. Because the candidate who was mistakenly listed first in the race had been the former chairman of the Board of Elections, some local political activists accused Godfrey’s office of attempting to influence the outcome, she said.

“They were trying to say we were trying to rig the election,” she said. “Somebody called and reported us to the state so we had an investigator come out.”

Godfrey issued a public apology at the next election board meeting.

“I said everybody makes mistakes,” Godfrey recalled. “I don’t know anybody who could have taken this job and not made a mistake.”

Moments like that got Godfrey down and had her wondering why she decided to become an election official in this volatile political environment. But there was another moment that provided an answer.

She said “a handicapped gentleman” called one day saying he wanted to be taken off the voter rolls because he couldn’t figure out how to send in his absentee ballot. Godfrey read the instructions to him over the phone and walked him through the process. When he later dropped his ballot off at the office, he thanked her and gave her a hug.

“It made my day,” Godfrey said. “And I just turned around and I had the biggest smile on my face and said, ‘You know, that’s one of the reasons I do what I do.’ "

Advertisement

Two days after Trump conjured chaos in Bibb County in early 2021, he repeated the allegation at the Jan. 6 rally in Washington, D.C., that fueled the US Capitol insurrection.

But the vote switching claimed by Trump never happened.

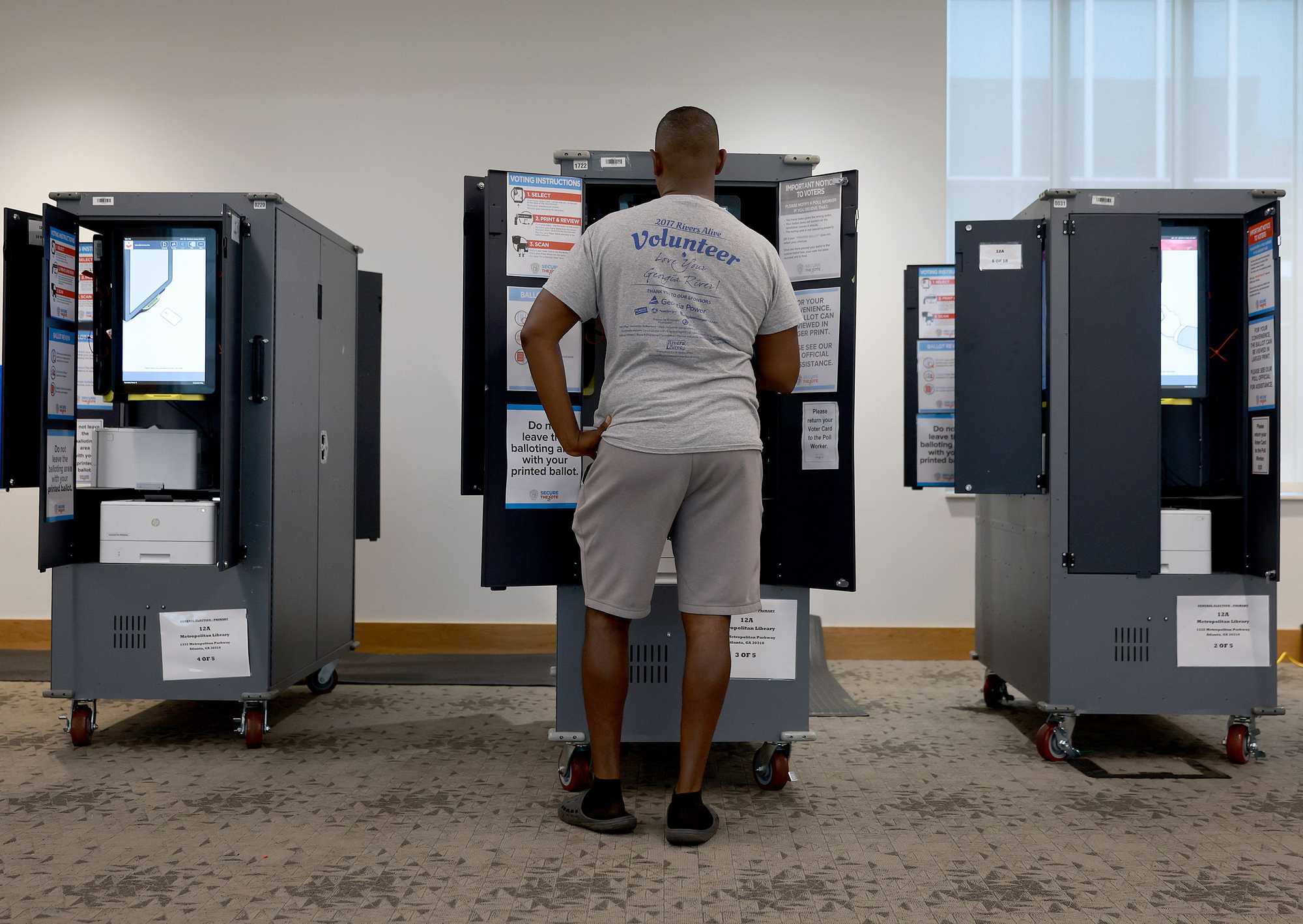

Election Night results showed Biden handily won Macon-Bibb County with 61.4 percent of the vote to Trump’s 37.6 percent — a margin of 16,883 votes out of roughly 70,000 cast. Amid the accusations about the election, the Georgia secretary of state’s office conducted two statewide recounts, including one in which all the ballots were tabulated by hand rather than machines.

They found microscopic discrepancies statewide and in Bibb County. The official results certified in December 2020 showed Biden won the county by 16,849 votes — a net gain of 34 votes for Trump.

To Trump and the deniers, the facts didn’t matter.

The allegation that more than 12,000 votes had been switched — interestingly just enough to swing the state to Trump — triggered threats, intimidation, and harassment of the county’s election workers during the runoff election the day after the Dalton rally. Trump supporters photographed their license plates and posted them on social media, followed workers bringing runoff ballots back to the election headquarters, and then demanded to come into areas of the building where they were not allowed, said Kaplan, an independent who chairs Macon-Bibb County’s five person Board of Elections.

“It didn’t get violent, but it was scary,” he said. The whole episode shook up Watson, Kaplan said. Watson’s husband declined a request to speak with her about the decision, saying she has not been discussing it with the media.

Herbert Spangler, a longtime Republican on the board, said he almost quit, too, in the face of threats and intimidation from members of his own party.

“You wouldn’t believe some of the e-mails and texts I got,” Spangler said. “I got so fed up.”

In the aftermath, Georgia Republicans passed the Election Integrity Act in early 2021 that includes new identification requirements to vote absentee, reduces the amount of time in which to request an absentee ballot, limits the use of ballot drop boxes, and adds complexities to the job of running elections.

Trump and his supporters focused a lot of their anger on Georgia’s Republican secretary of state, Brad Raffensperger, for certifying Biden’s victory. Among other changes, the law gives the state Legislature more influence over certifying elections and allows the state election board to suspend county election officials and appoint temporary replacements after conducting a performance review.

The Justice Department and civil rights groups have sued Georgia over the law. It is one of at least 42 restrictive voting laws enacted in 21 states since the start of 2021, according to the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonprofit law and public policy organization.

All the heightened attention in Georgia has been too much for some veteran elections supervisors, said Blake Evans, director of elections in the Georgia secretary of state’s office.

“The landscape of elections has changed as far as the public scrutiny that elections get,” he said. “That kind of intensified scrutiny is probably causing some folks, especially if they’ve been around 20 to 25 years, to say, ‘OK, maybe it’s time for me to retire.’ "

Advertisement

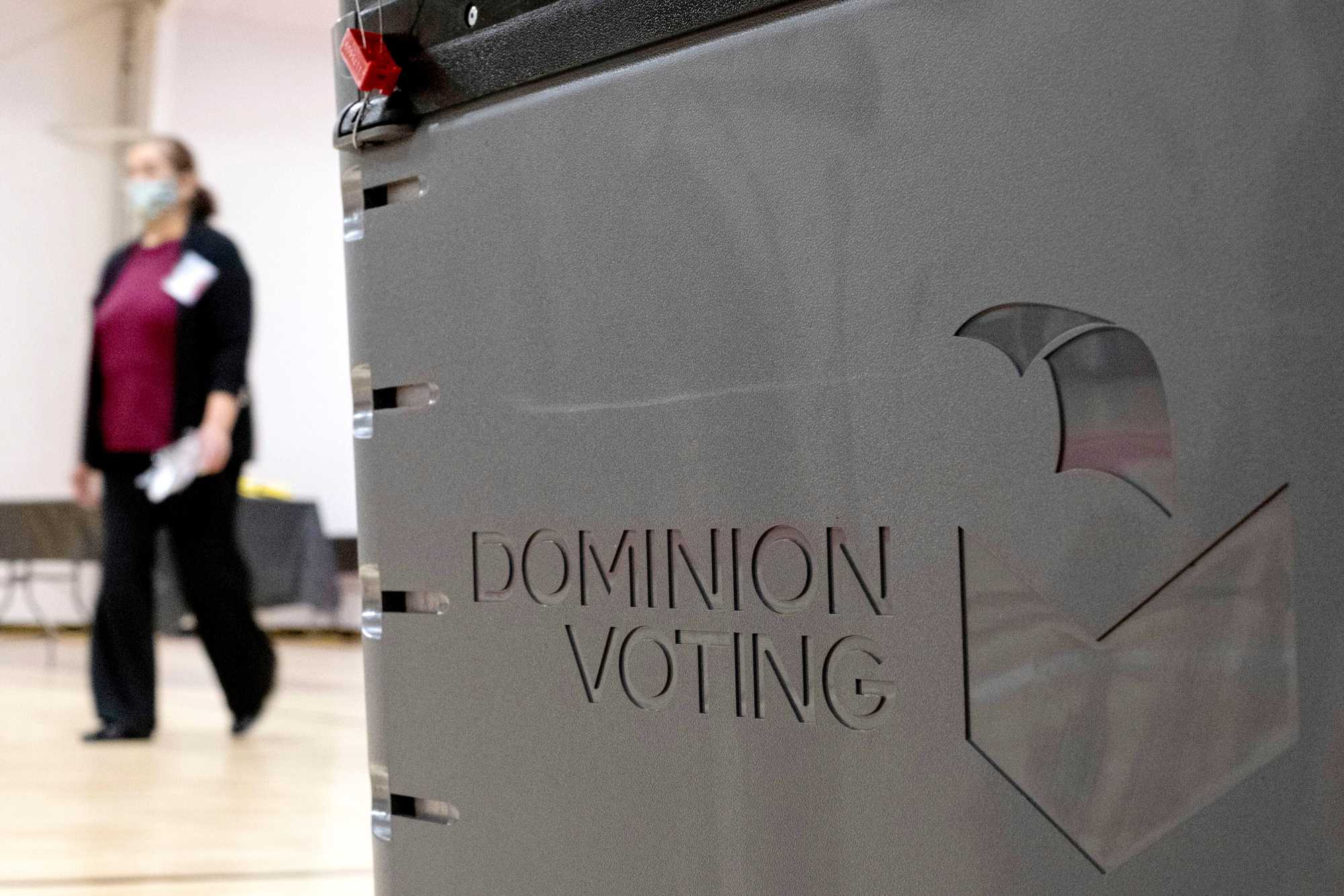

While the Macon-Bibb County Election Board searched for Watson’s permanent replacement, they tapped Gillon to run things on an interim basis. Gillon’s days now are spent juggling two jobs while preparing for the Nov. 8 election. He must make sure the Dominion Voting Systems ballot-marking machines the state began using in 2020 are working properly, all the supplies are ready, the county’s 31 polling places are lined up, and there are enough poll workers to staff them.

“I know the illusion is that elections just happen,” he said, answering e-mails in his office one September morning as a radio played Asia’s “In the Heat of the Moment” softly in the background. “They do not.”

One of Gillon’s hobbies is going to Star Wars conventions and dressing as a villain — a TIE fighter pilot to be exact. But he doesn’t want to be perceived as the bad guy in Bibb County on Election Day. He goes out of his way to explain to voters how the system works and to debunk conspiracy theories and outright lies.

Kaplan said the county was fortunate to have an experienced election worker like Gillon who could step in, particularly at a time when it’s difficult to fill those jobs. The problem isn’t just finding experienced people but the controversy that can erupt when trying to hire them.

Bibb County had 13 applicants for the elections supervisor position, Kaplan said. Only two had election experience. One was Gillon. The other was Canetra Ford, who had once been the county’s deputy registrar. The Board of Elections voted to recommend her for the job in April but the hire requires the approval of the County Commission. And after partisan social media posts from her became public, the County Commission decided not to act on the recommendation.

Macon Mayor Lester Miller, who is on the commission, said he planned to take responsibility for filling the job away from the Board of Elections and form a new selection committee. The board sued. Then in September, the Elections Board voted to recommend that Gillon be hired permanently. But his approval is now caught up in a legal dispute that’s unlikely to get resolved before the Nov. 8 election.

Kaplan said it shows how fraught and combustible Georgia elections have become.

“Nobody gave a damn who the elections supervisor was,” he said of before 2020. “Everybody gives a [expletive] now.”

The situation remains in limbo as Gillon prepares to run his first general election in the state that could, once again, be at the center of the storm.

Jess Bidgood, Tal Kopan, Shannon Coan, Sarah Ryley, and Lissandra Villa Huerta of the Globe staff contributed to this report.

Credits

- Reporters: Jess Bidgood, Jim Puzzanghera, Tal Kopan

- Editors: Scott Allen, Mark Morrow, Jen Peter

- Multimedia editor: Christina Prignano

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development and graphics: Daigo Fujiwara

- Photo editors: William Greene and Kim Chapin

- Audio editors: Scott Helman and Jesse Remedios

- Copy editors: Mary Creane and Michael J. Bailey

- Data analysis: Shannon Coan and Sarah Ryley

- Audience engagement: Lauren Booker

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

© 2022 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC