Nothing about the brown UPS delivery truck with the license plate R98004 stands out much, as it crawls through the clogged streets of downtown Boston each day, delivering the goods to satisfy our insatiable need to get everything we want, whenever we want.

Except for this: Over the past four years, R98004 has become the most ticketed vehicle in all of Boston — with over 1,550 parking violations — doing way more than its share to make Boston’s traffic congestion, already some of the worst in the nation, that much more severe and ceaseless.

How do we know? We followed it.

On one fall Friday, the Globe Spotlight Team spotted the truck illegally parked for fully 5 hours and 6 minutes of a 7 hour and 7 minute span during its shift.

It paused in a tow zone, where it blocked a lane of downtown traffic for nearly an hour. Then on to another tow zone, before wildly overstaying its welcome by spending more than 3 hours in a 30-minute commercial parking space.

On many days, you can spy a bright orange parking ticket sticking out under the windshield wiper or stuffed into a container overflowing with others just like it: In the first half of 2019 alone, the truck amassed 238 tickets. And in all that time, it was never booted or towed.

Why? Because UPS has a formal agreement with the city that its vehicles will not be booted, no matter how many tickets they accrue. Same goes for many FedEx trucks, making their rounds. The deal works for everyone — the city that feasts on the ticket fines, the UPS truck that doesn’t have to search for a parking spot, and the consumer who gets his new shoes just a day after ordering them online — everyone, that is, except the rest of us, trying and failing to get from here to there on our city’s narrow, winding, overstuffed streets.

That boxy delivery truck blocking your lane is just one maddening manifestation of a public failure to adapt to the new convenience economy. The technology built around our desire for instant gratification — Uber and Lyft, DoorDash and Grubhub, the Amazon packages whizzing from distribution centers to our doorsteps — has become the source of huge amounts of new traffic. Hundreds of thousands of these trips would never have happened just a few years ago.

But the public policy response has been no match for this challenge, the Globe Spotlight Team has found. In Boston, in fact, the operative policy only enables the offender.

Join us live to discuss our reporting and possible solutions to Boston’s commuting crisis.

About this eventIt is part of a pattern of delayed or passive public response to our slow-moving — very slow-moving — crisis in commuting. True, state officials were a nose ahead of the pack in imposing a surcharge on Uber and Lyft rides three years ago — an attempt at the time to make the companies pay their share of transportation costs — but now they have fallen out of the vanguard. Confronted by the powerful ride-share lobby on Beacon Hill, state leaders haven’t summoned the will or nerve to impose the kind of high fees and stringent limits other cities are using to try to curb the traffic.

The result is obvious to anyone who drives or walks in congested areas. Deliveries of online purchases in Boston’s metro region surged by more than 90 percent from 2010 to 2018, data shows, blocking travel lanes, crosswalks, handicapped ramps, and hydrants as they come and go.

Ride-hailing vehicles have also become ubiquitous since arriving in our city about seven years ago, accounting for a growing share of cars on the road on some of our busiest streets.

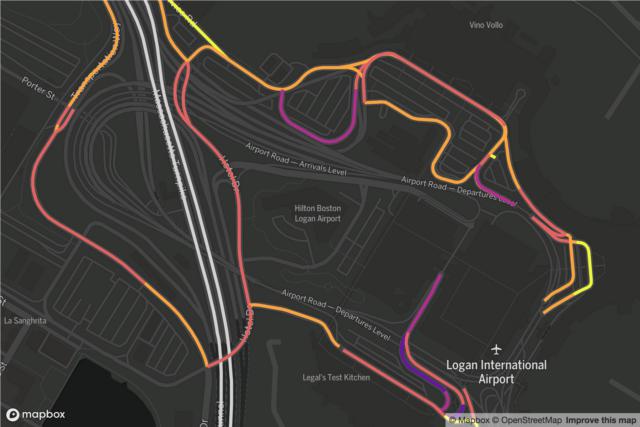

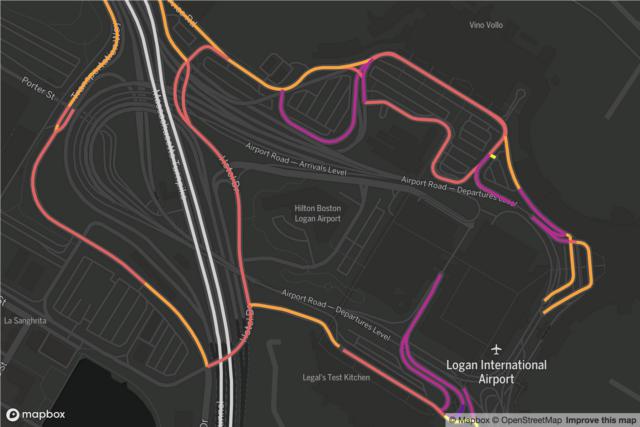

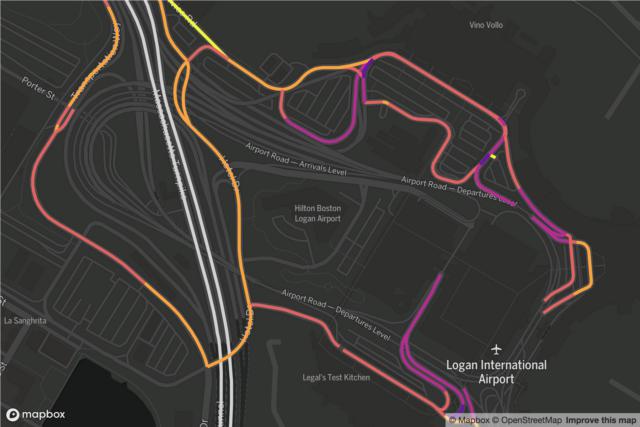

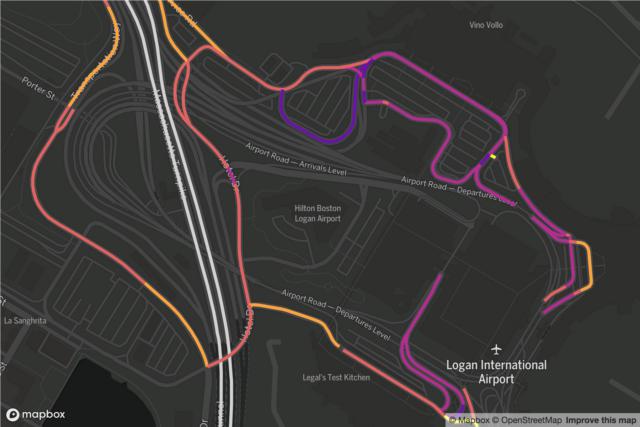

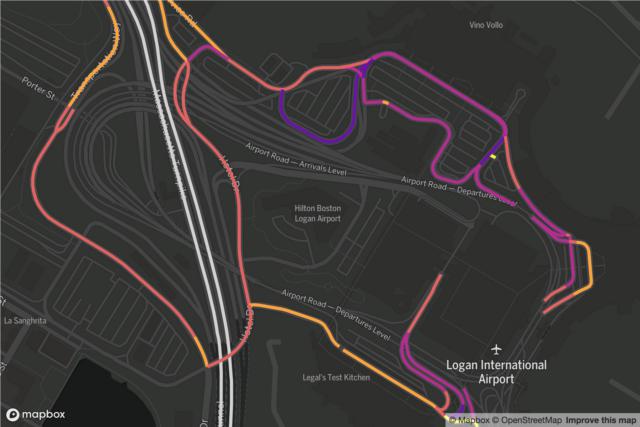

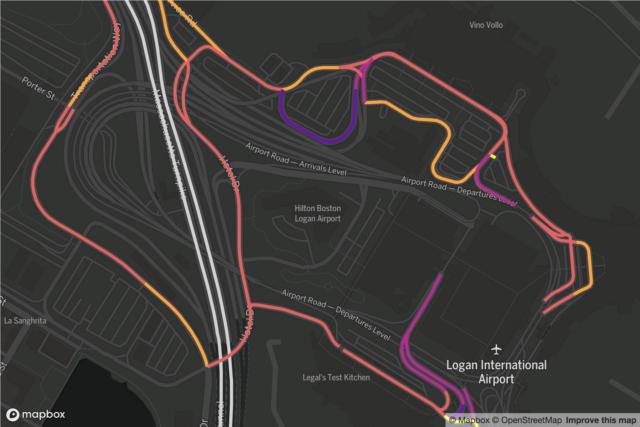

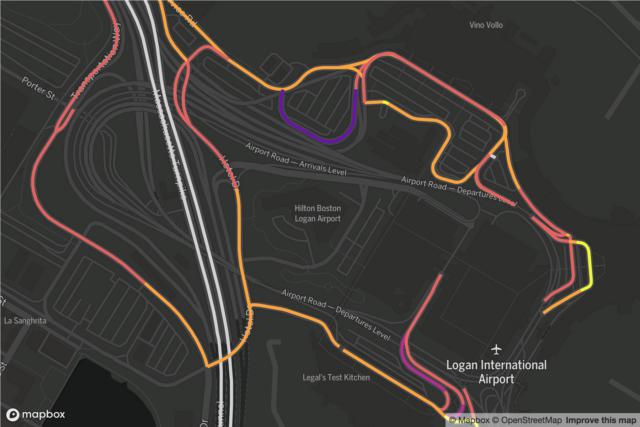

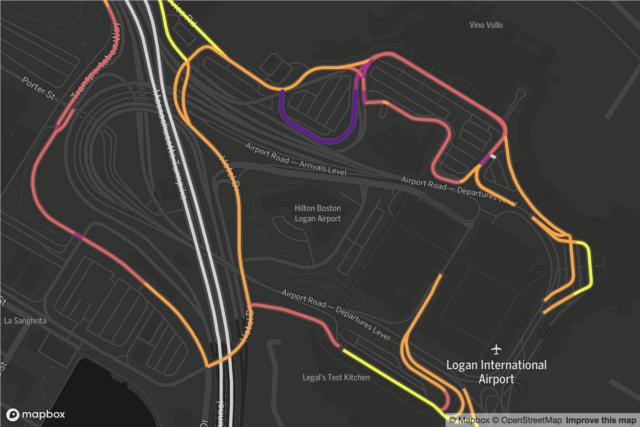

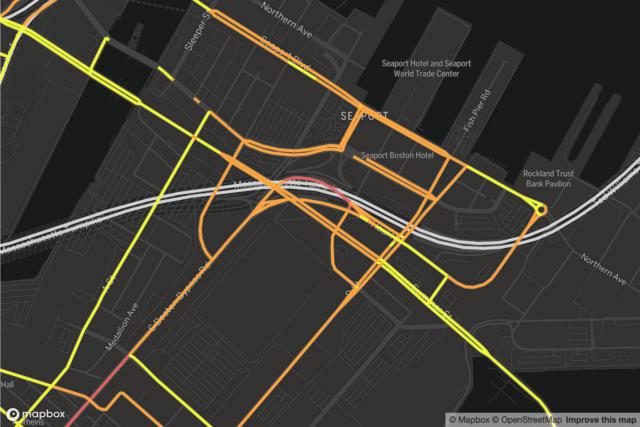

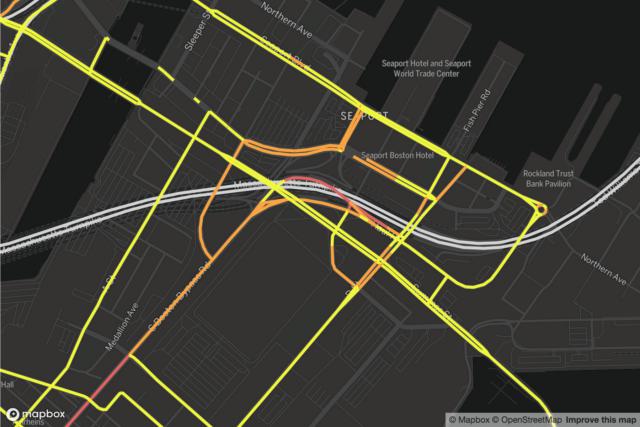

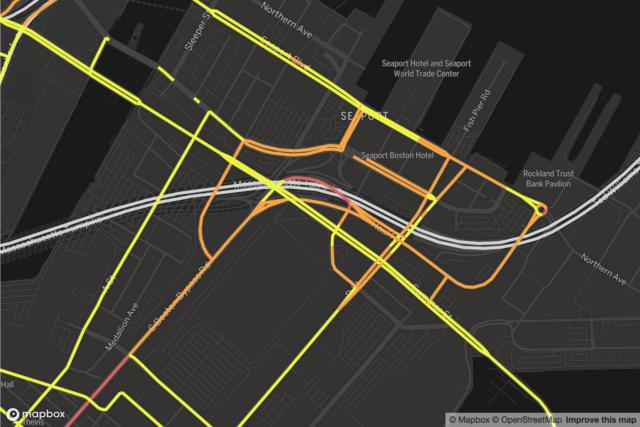

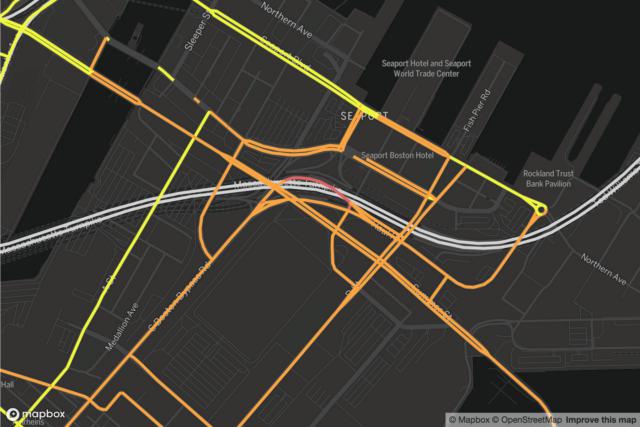

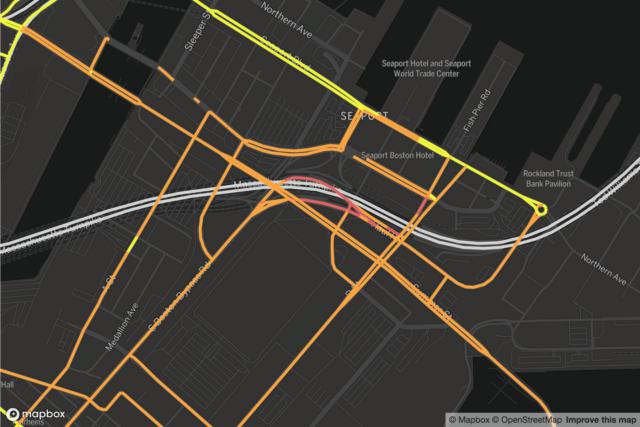

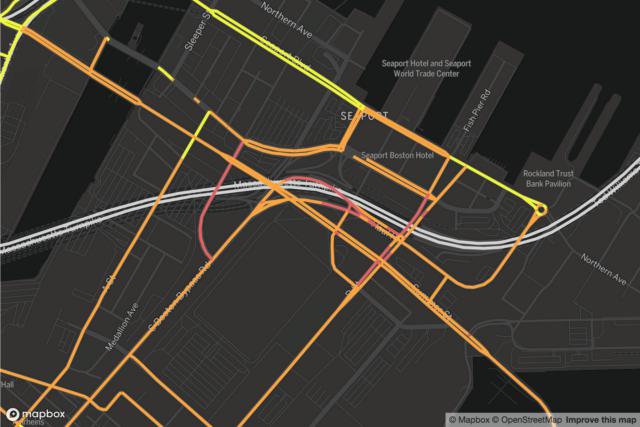

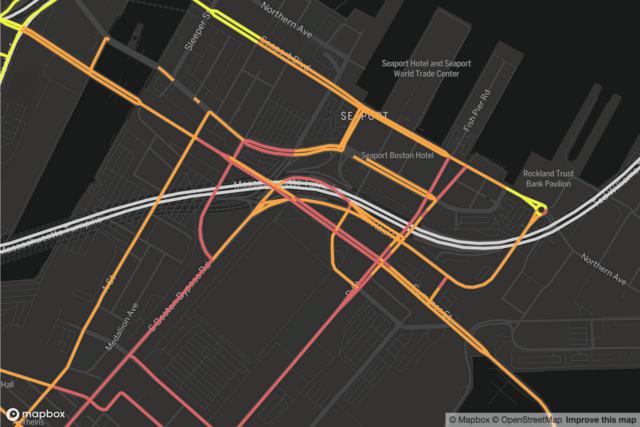

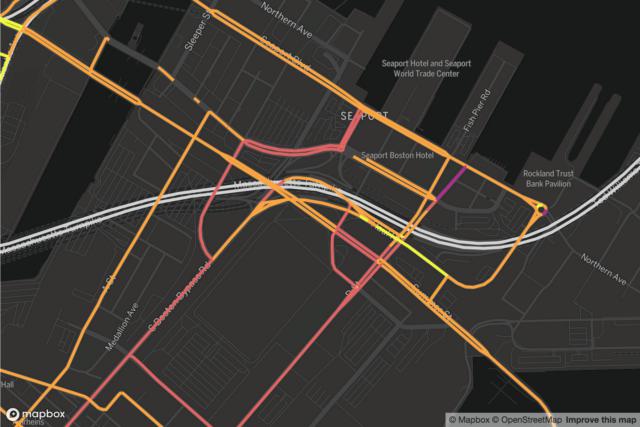

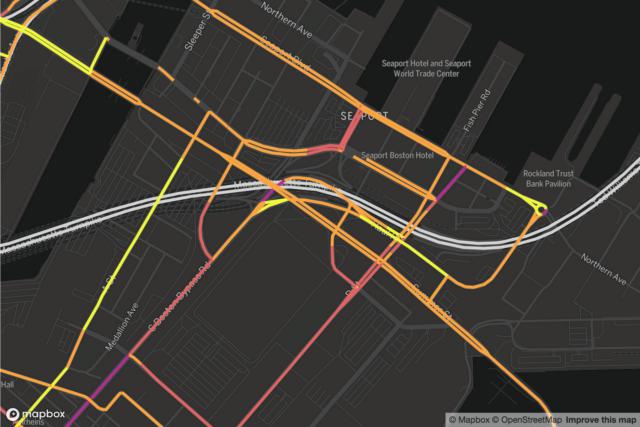

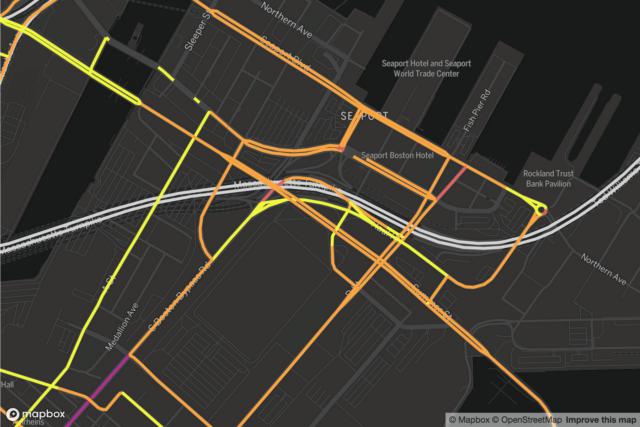

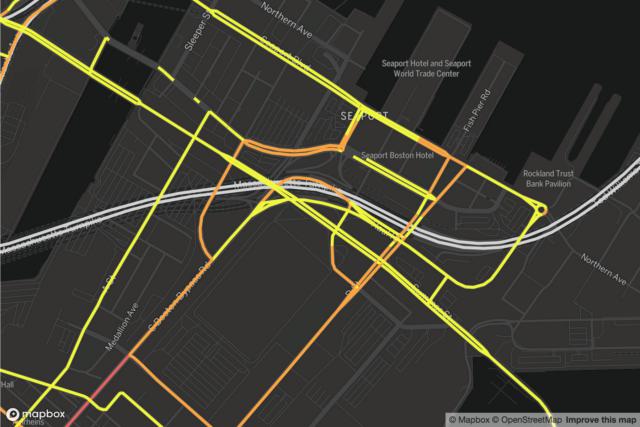

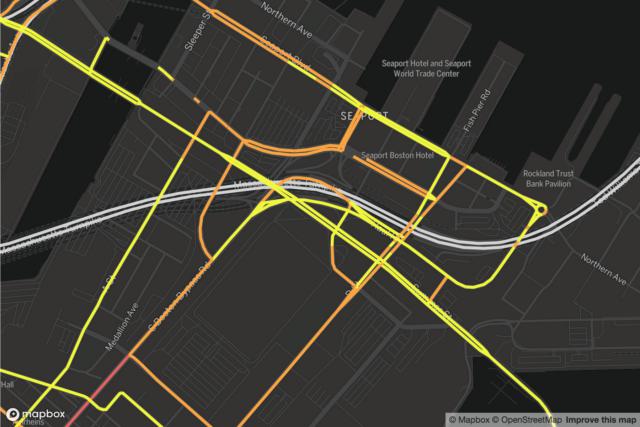

Try driving down a portion of D Street in the Seaport at 2 p.m. to 3 p.m. where up to one out of five trips are by ride-hailing cars, according to new estimates from transportation analytics company StreetLight. Or take in the traffic on the streets near Logan International Airport: At any hour from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m., on at least one road in the area, at least 15 percent of trips — and sometimes more than 20 percent — are made by Uber and Lyft cars.

Nearly half the time, ride-hailing vehicles aren’t carrying passengers at all, according to one study using data from Uber and Lyft, but driving to meet one or trolling to find one.

These are just some of the unforeseen and unaddressed consequences of technological innovation. We have a habit of not connecting the convenience on one end — the merchandise arriving on our doorstep at warp speed — with the inconvenience on the other. A scofflaw delivery truck, perhaps. You know the one.

New challenges lie ahead, such as the self-driving cars that could soon swarm our streets. These futuristic vehicles are already being tested on the public roadways in Boston’s Seaport and could branch out into even busier areas soon. Will these vehicles make our commutes safer and more efficient, as promised, or simply lead to still more cars clogging the streets?

And if the answer is the latter, will public officials do anything about it?

They’d better, say experts such as Bruce Schaller, a transportation consultant.

“It’s fundamentally important for cities to manage the growth of vehicle use,” the former New York City transportation official said. “Otherwise, they’ll suffocate.”

FALLING BEHIND ON LEGISLATION

When Uber and Lyft entered the Boston market earlier this decade, they promised a lot.

The new alternative to taxis would give marginalized communities like Roxbury and Dorchester, where cabs rarely went, better transportation; provide late-night revelers in bars with a safer route home; remain a complement — not a competitor — to public transit; and cut down on carbon dioxide emissions that contribute to climate change.

Less discussed was another contribution — traffic.

As cab usage has plummeted — from 14.6 million rides in 2012 to 4.8 million rides six years later, Boston police say — ride-hailing trips have soared to levels the taxi fleet never approached.

In 2018, Uber and Lyft provided 42 million trips in the city and more than 81 million across the state, according to data the firms provided the state.

This summer, a study financed by the two companies showed ride-for-hire vehicles made up an estimated 8 percent of the 312 million driven miles in Suffolk County in September 2018. That rate is less than the one in San Francisco County, where Uber is based, but more than in the counties home to Seattle, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C.

It sounds like a modest number, 8 percent. In the world of traffic, it is anything but.

“As long as you’re well below the capacity of the road, adding a few cars doesn’t matter,” said Peter Furth, a civil engineering professor at Northeastern University who specializes in transit and traffic. “But once you get near capacity, a few more can take you over the cliff.”

Uber and Lyft aren’t just devouring the market once controlled by medallioned cabs, they’re drawing in customers who never would have taken a car to their destination in the first place.

That spells congestion.

Gregory Erhardt, a University of Kentucky professor who has studied the effects of these ride-hailing companies, said the reality is contrary to their rosy marketing pitch. In a ground-breaking study, he found that about half of the new congestion in San Francisco could be attributed to customers using ride-hailing apps.

“There’s this idea that they’re eco-friendly, and you should invite them,” he said. “But it turns out, it hasn’t lived up to that promise.”

Asked about the contention that its service worsens traffic, an Uber spokesman questioned the accuracy of the street-level data for the Boston area provided to the Globe, and said many of its rides are taken outside rush-hour. Uber and Lyft officials both pointed at the state’s recent congestion report, which estimated that trips from their companies accounted for about 4 percent of vehicle trips in Boston.

“We share the state’s goals of reducing congestion and investing in mass transit, but proposals should not scapegoat ride-share customers to protect car owners and delivery trucks,” said Harry Hartfield, an Uber spokesman.

Again, the 4 percent figure it is a small-sounding number but one that can trigger an outsized effect in Boston.

Drawing on an exclusive analysis by StreetLight, the Spotlight Team pinpointed places in town where that effect is especially pronounced. On the John F. Fitzgerald Surface Road near the Financial District, at 4 p.m. to 5 p.m., for example, up to 15 percent of the trips are from ride-hailing or delivery service cars.

Transportation experts have started calling for more aggressive government intervention to rein in Ubers and Lyfts because of another troubling side-effect of their popularity: They undermine mass transit. About 42 percent of Uber and Lyft riders surveyed in the Greater Boston area said they would have otherwise taken a bus or train, and another 12 percent would have walked or biked instead, according to a study by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council.

Barred from city cab stands, Uber and Lyft drivers are also a major source of other familiar irritations — cars stopped or parked where they shouldn’t be, doors opening in the middle of the street or in the path of bicycle commuters to take in passengers.

“It’s just an absolute nightmare right now trying to safely get around on a bike,” said Peter Doherty, a Somerville resident who commutes to downtown Boston. “It’s an unmarked car just stopping in weird locations, and doors are popping open.”

When the Legislature first passed a bill regulating Ubers and Lyfts in 2016, such effects were just beginning to be felt. The legislation included a fee of 20 cents per ride, one of the first surcharges on such rides in the nation. The proceeds were meant to help fund state and city transportation projects and provide some financial aid to taxi drivers hammered by the new competition.

But three years and tens of millions of Uber and Lyft rides later, Massachusetts has already fallen behind many other governments in both fees and regulations.

Such cities as New York are now taking stronger stands against the ride-hailing companies, insisting these private operators that rely on taxpayer-funded roadways and law enforcement services pay their fair share of public fees. The city charges Uber and Lyft a whopping $2.75 per ride for vehicles travelling in one part of the city and less for rides that are shared, as a way of incentivizing carpooling.

In New York, a city with a vast cab fleet, the Taxi and Limousine Commission has enormous clout compared to the regulatory agencies in Massachusetts that deal with ride-hailing companies. New York City last year went so far as to temporarily halt all licensing for new Uber and Lyft vehicles, among the most aggressive steps taken by any American city.

Uber and Lyft fees per ride

New York City*

$2.75

D.C.

6%

Portland, Ore.

50¢

Seattle

24¢

Mass.

20¢

* Only applies in certain sections of the city

It’s not just New York. In Seattle, Uber and Lyft vehicles are charged 24 cents per ride, but the mayor has suggested increasing that price nearly three-fold, a move that prompted Lyft to send messages to its customers decrying the attempt.

The City of Boston has publicly testified in favor of Beacon Hill legislation that would charge a 6.25 percent fee — equal to the state sales tax — on rides, with lower fee for shared rides, but there has been minimal movement on the suggestion. For a $10 solo ride, that would be equivalent to a 62-cent fee.

Transit advocates say a stronger regime of fees and regulations would enable the state not just to raise money, but to change how people think about the way they get around town.

“The first time around, [the state] was collecting the fee thinking about the impact to the transportation system,” said Lizzi Weyant, governmental affairs director for the Metropolitan Area Planning Council. “But now it’s also about changing the behavior of [ride-hailing] users… . We have the chance to … encourage them to think about their travel and invest their money to make public transportation stronger.”

Any efforts by legislators to impose higher fees or stronger limits are likely to be met with strong debate on Beacon Hill. Ride-hailing firms are relatively new, but they have been quick to invest in the oldest political art — influence. Since 2014, Lyft has spent more than $373,000 on lobbying on Beacon Hill; Uber has spent more than $1.4 million since 2012, on issues ranging from ride-hailing fees to autonomous vehicles.

Their clout was vividly displayed earlier this year when MassPort attempted to raise its $3.25 fee for pick-ups from the airport to $5 for both pick-ups and drop-offs. The agency had noticed that the state’s airport fees for ride-hailing vehicles were falling behind several other travel hubs, such as Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and Oakland, and wanted to catch up.

But after pushback from the companies and their advocates, the agency decided to only add a $3.25 fee to drop-offs at the airport. What would have been one of the highest fees in the nation thus remains one in the middle of the pack.

Still, Uber and Lyft have faced some government limits. Their passengers at the airport are now dropped off and picked up at a central parking garage at most hours, rather than at the curb, limiting disruptions caused by drivers who stop in the middle of a lane to pick up a fare. Separately, the City of Boston also introduced a pilot program to designate certain sections of curb as official ride-hailing pick-up and drop-off zones in the Fenway district from 5 p.m. to 8 a.m., though the city has given no indication it will become permanent. Another similar pilot program was put in place in the Seaport.

Governor Charlie Baker has been characteristically cautious about raising fees on Uber and Lyft. He has instead proposed a bill that would require the companies to provide more specific data about where and when trips start and end, so cities can better manage them.

State Transportation Secretary Stephanie Pollack told the Globe the Baker administration is open to further ride-hailing measures and said she supports the airport’s move to cut down on such trips. But she declined to say whether the administration would support raising the fees outside of trips to and from the airport to help change travel behavior.

“I think it should be a policy debate,” she said.

DELIVERY SERVICES CLOG STREETS

The I-want-it-now-and-I-want-it-delivered economy is in the ascendant, and the drivers who make that proposition work are struggling to keep up. There are thousands of promises to keep, and nowhere to park.

Juan Reinoso knows that well. He said he would rather stop in a legal parking spot when he’s delivering Uber Eats meals to people after he wraps up his shift in a university cafeteria. But as he tried to scout for parking in front of Harvard Square’s Sweetgreen restaurant, it seemed impossible.

“See, what are you supposed to do in this situation?” he asked. “It’s just the way that Boston is made.”

He settled on temporarily blocking a crosswalk in front of a fire hydrant, before dashing out of his car to pick up a salad order for his next customer.

Business is brisk. “It’s the future. It’s comfortable, and people like it,” he said.

And the traffic that comes with it is bound to get worse, as food delivery trucks, Amazon, and United Parcel Service hit the streets with ever greater regularity. For each month from September 2017 to July 2018, for example, the total sales of the main food delivery companies in Boston — Caviar, DoorDash, Grubhub, Postmates, and Uber Eats — grew more than 60 percent compared to the same month in the previous year, according to figures from Second Measure, a California-based analytics firm.

The companies declined to release data on the exact number of their delivery trips in the Boston area. But one researcher who tracks the market estimates that about 1.6 million online purchases, including on-demand food orders, are delivered every day in the Boston metro area, compared to just under 823,000 in 2010. That’s an increase of more than 90 percent, according to Jose Holguin-Veras, the director of the Center for Sustainable Urban Freight Systems at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y.

What’s to be done about this convenience-driven crush? Boston’s former chief information officer, Jascha Franklin-Hodge, said he hopes cities will experiment with more sophisticated approaches to this new road usage.

“A car trying to get to a restaurant, doing a pick-up, and coming to my house in the middle of rush hour is causing much more of an impact than if it’s happening once the rush is over,” said Franklin-Hodge. “So the question is: How would I start to think about policies that don’t say, ‘You can’t have food delivered at 5:30,’ but say, ‘Hey, maybe you should pay a little more on that,’ as a way to encourage people to be thoughtful?”

Boston has tried nothing like that. But it has long made life easier by relaxing parking enforcement for companies like UPS, which was ticketed more than 51,000 times over the last four years, with fines of anywhere from $15 to $120 per offense, according to an analysis by the Globe.

The most common offense was for double-parking, which by definition means blocking a travel lane.

UPS is just one of nearly 300 companies that have a deal enabling them to incur a limitless number of parking tickets without getting booted, as long as they promise to pay them within a certain time. The list includes construction and electrical companies, as well as several courier companies. In total, the agreements, also found in other cities, protect more than 1,100 UPS trucks and about 200 Federal Express trucks in Boston.

Kim Krebs, a spokeswoman for UPS, said that the company struggles to find enough commercial parking spots — and that cities should stop prioritizing curb space for personal vehicles.

“We’re actively engaged with city officials and looking for solutions that make it easier to deliver while reducing congestion and enhancing sustainability methods and quality of life for Bostonians,” she said in a statement.

In Boston, Mayor Martin J. Walsh said the city has increased parking fines to help reduce illegal parking, including in loading zones — theoretically a change that should free up spaces for delivery vehicles to use. But Chris Osgood, the mayor’s chief of streets, said the city knows it must do more.

This project was possible because of Globe subscribers. If you don’t subscribe yet, please support our work here.

Subscribe now“Commercial parking is an issue that we need to think about how we actually get more … trucks to the curb, and that is about making space available and about managing them,” he said.

Other cities are already well ahead, trying to tackle the problem in more innovative ways: In Manhattan, the city provides incentives to companies that are willing to deliver goods overnight — from 7 p.m. to 6 a.m. — to cut down on traffic and emissions from trucks waiting in congestion. The city has reported it will expand the program, building off the successful pilot.

But in Boston, Walsh and Osgood say they’re not planning on testing such a program, fearing it could be an unwelcome night-time disruption in residential neighborhoods.

SELF-DRIVING CARS POSE A NEW TEST

It’s not exactly George Jetson’s flying car, but even now, the beginning of the newest revolution in transportation can be seen tooling around the edges of Boston’s Seaport District. Less than a mile from Harpoon Brewery and down the street from a Dunkin’, it’s not uncommon to see a boxy four- or six-seat self-driving shuttle making its way near the office buildings of the Innovation and Design Center. Here, the two most prominent self-driving car companies in Boston, Optimus Ride and Aptiv, are already promising that we could see an autonomous vehicle without someone directly in the driver’s seat in the near future.

Companies promoting self-driving cars say that such cars could potentially reduce traffic, as vehicles move more efficiently among one another.

The reality could be less rosy. Traffic could be brought to a near standstill if and when autonomous vehicles are finally popularized, according to current research. Adam Millard-Ball, of University of California Santa Cruz, has found that, if given the chance, autonomous ride-hail vehicles would create more congestion on city streets by aimlessly driving as they waited to give the next ride, rather than paying for expensive parking in city centers. For example, even 2,000 self-driving cars could, he estimated, slow traffic on certain streets in downtown San Francisco to less than 2 miles per hour as they try to kill time.

In many ways, the rise of self-driving cars could mirror the history of Ubers and Lyft, which were largely unfamiliar to people — until they were everywhere. In suburban Phoenix, hundreds of white self-driving vans are powered by Waymo, a unit of Google’s parent company, Alphabet. In sections of four nondescript suburban subdivisions, the largest fleet of autonomous vehicles on American roads has been ferrying passengers in a pilot program, which still includes an employee in the driver’s seat as a precaution. Residents say they’ll see several self-driving Waymo cars each day, sometimes whizzing down major thoroughfares at 40 miles per hour.

One day this summer, Andrea Depew and her daughter used her phone to summon a self-driving car to their home in Chandler, Ariz. to take a trip to a nearby shaved ice store — just as they would call a normal Lyft. The car arrived with someone in the driver’s seat, but he was barely touching the steering wheel as it twisted in his hands.

“I think it feels pretty normal to be in one,” said Depew, who uses the program several times a month.

Her daughter, Madelyn, knows she’s in a vehicle on the cutting edge of technology but increasingly, she said, it feels like a normal part of daily life.

“I know what it’s like,” said the 14-year-old. “It feels familiar.”

Some experts say that sort of easy familiarity will almost certainly lead to even more traffic for cities that already struggle with congestion. While the easy availability of driverless cars may reduce parking and car ownership, forecasts suggest that autonomous vehicles themselves will cause a 30 percent increase in driven miles.

For now, cities seem most concerned with a more obvious worry — the safety of such vehicles, especially after an autonomous car from Uber, a major Waymo competitor, killed a woman crossing the street near Phoenix in 2018, prompting Uber to pull its autonomous vehicles from public use.

But there are concrete steps that cities or the state could take to save regions from autonomous vehicle gridlock: charge cars for their driving time on certain streets at certain times or for the number of miles traveled. Subways and buses could also eventually employ self-driving technology, since a better-functioning public transit system could lure more people out of individual cars.

In the meantime, the riding public is unsure of what to expect. Outside One Seaport, fresh from a birthday celebration and not far from the headquarters of Boston’s self-driving car companies, Briana O’Leary and James Gregoire were split on what autonomous vehicles would mean for Boston’s traffic nightmares.

Gregoire said autonomous vehicles will help congestion because they are pre-programmed to be better drivers than humans. But O’Leary imagined that self-driving cars may only make traffic worse if everyone takes advantage of this new technology by taking more solo rides.

“My question is, how do self-driving cars change the number of cars on the road?” she asked.

It is the question of the hour. But there was no way to settle it, so the two soon headed for their waiting car across the street — a vehicle from Lyft.

Nicole Dungca can be reached at [email protected], and she can be followed on Twitter at @ndungca. Saurabh Datar can be reached at [email protected], and he can be followed on Twitter at @ssdatar. Tips and comments about this Spotlight series can be sent to [email protected].

The Globe worked with StreetLight, which collects its data and generates metrics through its platform that uses sources that include anonymized location records from opted-in smartphone apps and vehicle navigation devices. The metrics have been validated using thousands of North American traffic counters, including more than 330 installed by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation. The metrics describe aggregate groups of travelers, not individuals. Neither StreetLight nor the Globe can identify individual users or devices.

To analyze travel patterns of vehicles using on-demand app services such as Uber, Lyft, UberEats, DoorDash, and GrubHub, the company observed nearly 80,000 trips in and around Logan airport from April to December 2018. By combining such data with statistics reported from Logan airport, the census, and the state, the company computed estimates for drivers working for on-demand app services at various times throughout the day. The firm observed about 758,500 ride-share and delivery trips total for its analysis. The large majority of trips are estimated to be from services such as Uber and Lyft, rather than food delivery services, according to StreetLight.

StreetLight’s methodology observed the movement patterns of devices to determine whether the driver uses such apps. Those drivers who aren’t using such apps tend to make fewer stops and travel in more direct paths than a driver who is working as a ride-share driver or food delivery app driver.