Beyond the gilded gate

One house, One family,and

thefading dream ofhomeownership

Watertown

Just about every day, Mary Logue sinks into her beige sofa and admires the home she inherited a half century ago.

“This house,” she nearly whispers, “is everything.”

The modest two-family in East Watertown has been alive with the chatter of nightly dinners and family squabbles since 1943, when Mary’s aunt and uncle bought it. Tucked on a quiet street, the home would easily fit into many neighborhoods around Greater Boston. Square and green, the twin front doors framed by vertical lattice fencing. Step inside, and the carpeted stairs wind around a corner to an upstairs apartment that smells of yellowing magazines and baby powder, filled with artifacts from Mary’s 90 years: TV guides, framed photos, and tchotchkes dubbing her “World’s Greatest Grandma.” Her son, James, and his wife live downstairs.

It used to be the kind of place someone could buy on a single income with a working-class paycheck, perhaps an immigrant family like the one that raised Mary.

That is not true anymore. Not in the place Greater Boston has become.

Mary is keenly aware of that fact: She still lives on Dartmouth Street, a five-minute walk from the apartment she grew up in. But most of her children and grandchildren have retreated to Lynn or Waltham or Cambridge in order to find a place, pooling pennies for down payments or renting for sums she can barely fathom. Often, Mary wonders why the plastic four-leaf clovers scattered around her dining room have brought her grandchildren so little luck.

“They say there’s no way they can buy a place right now,” she says. “And they might be right.”

Theirs is a sadly common story around this region, where homeownership, once the traditional marker of American adulthood, has flown out of the grasp for so many. The typical house in Massachusetts once sold for three times the median household income — a reach, but manageable. Today, it sells for eight times the median household income. The age of the median first-time homebuyer nationwide climbed from 29 in 1981 to 36 in 2022, and a growing share of people here pour their income into rent, rather than a mortgage.

At the core of the problem are “age-old supply and demand issues,” said Chris Herbert, managing director of the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University. The math is simple: More people want to live here than there are places for them to live, and most towns refuse to do anything to change that.

Across four generations, Mary’s family is a case study in what that means for the typical Greater Bostonian, an example of how a homeownership system that once spurred wealth and lifted millions to better, more stable lives is failing many today. Within 100 years, her clan has watched the seams of the American Dream coming apart — one stitch, one generation at a time.

This is how it happened.

Advertisement

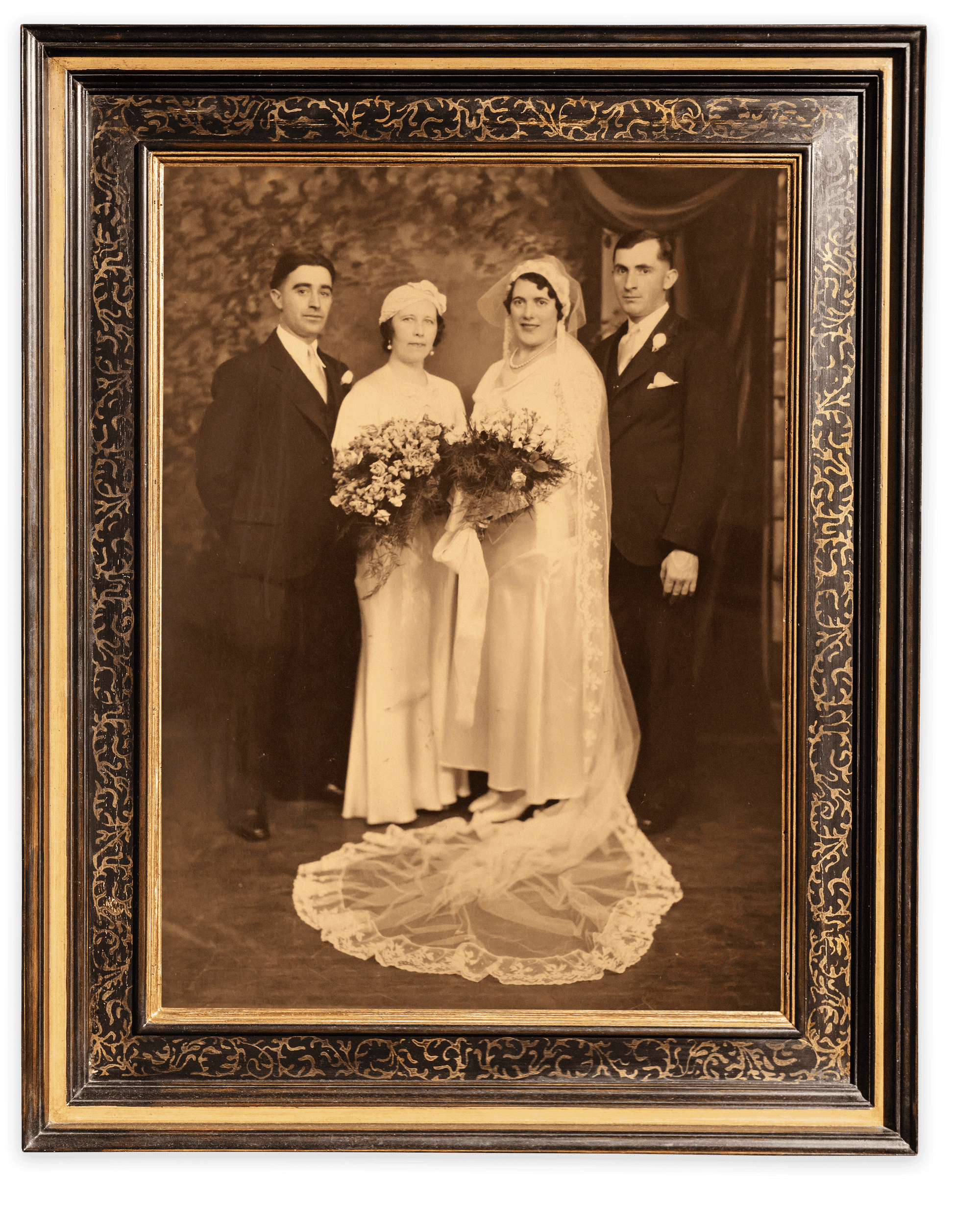

Mary’s father’s family — the Kevilles — journeyed to the states in the 1920s with no more than $25 on their person. Their hometown of Tuam, Ireland, was rural and poor with a shrinking population and lingering memories of the Potato Famine. As family lore goes, one relative was shot 32 times while serving in the Irish Republican Army.

America promised cultural freedom, better jobs, a home.

The family landed here as the economy boomed and Irish immigrants were already ascending the rungs of class and income. Patrick, Mary’s father, settled into a small apartment in Cambridge with his brother, James — a name that would prove exceptionally popular in this family. Their future wives, Winifred and Catherine, took jobs as cooks and caretakers.

Unknowingly, the Kevilles had arrived in Boston just before home buying changed dramatically. Before the 1930s, urban Americans mostly rented, leaving owner-occupied residential property reserved for the well-off: summer homes, rural estates, and city mansions. Only after the Great Depression did the country adopt a housing policy that helped everyday people buy into the market. New laws made lending and mortgages far more accessible, reducing down payments and lengthening terms to create monthly payments working people could afford. Eventually, the 30-year mortgage — an agreement that would later be dubbed “The American Mortgage” — became the standard.

Americans of all incomes — white ones, anyway, as many Black neighborhoods were locked out through redlining and raw prejudice — benefitted. Mary’s parents, Patrick and Winifred, bought 39a Chapman Street in Watertown for an unknown sum. But for reasons obscured by the sands of time, they lost it in the late 1930s. Her uncle and aunt, James and Catherine, were luckier: They purchased the Dartmouth Street home for $6,000, roughly four and a half times their annual household income of $1,300. The mortgage each month was $34.10, the equivalent of $619 today.

It stood outside the bustle of the city, but close enough to access the bounty of Boston on the now-defunct Green Line branch that ended at Watertown Square. The building itself was constructed in 1920 as part of a swath of multifamily buildings made to house workers from the US Arsenal and Hood Rubber Company. On its short block stood 24 such buildings with grassy yards and black mailboxes brimming with envelopes. Around it, East Watertown provided a haven for a hodgepodge of immigrant families — Armenian, Italian, Greek, Irish.

Buying the two-family transformed James and Catherine from tenants to landlords. They rented out the downstairs unit to help pay the mortgage and lived upstairs themselves, sleeping in separate bedrooms and keeping parakeets as pets.

They had no children. But what they did have was the foundation of financial security. How could James and Catherine have known the two-family would bolster great-grandnephews and nieces they had not yet imagined? A lifetime later, the house remains in the hands of their relatives, worth nearly nine times what they paid for it after accounting for 80 years of inflation, and provides shelter in a region roiled by a housing crisis.

“That is the Logue family home base,” James Patrick Logue III, a great-grandnephew of James and Catherine, said recently. “Who knows where we would be without it?”

One family through the decades

The home of the Keville-Logue family has offered shelter for generations. See scenes from family life through the years.

Mary learned to walk and spell in a rental two blocks from Dartmouth Street. Her parents baked Irish soda bread and stuffed Brillo pads in the piping to keep rats away. It was a simple existence, Mary said, one where they “made do or did without.”

But by the time she came of age in the ‘50s, a golden era of American homeownership had dawned. Massive postwar demand for housing cleared a path to build waves of inexpensive homes around Boston. Wraparound porches and fenced four-bedrooms became newcomers’ suburban idyll. Rows of homes sprouted neatly on the west side of Watertown near St. Patrick’s Cemetery, where Mary’s father and uncle were eventually buried side by side. The home on Dartmouth Street was left to James’s wife, Catherine.

It was a time when just about every man with a job could afford to own. Mary and her husband, James Logue, were no exception.

They first locked eyes across the dance floor at Hibernian Hall in Roxbury and wed in 1953. Within five years, their family had grown to include two boys and a girl. And even as Watertown factories faded, the tight-knit community promised them a warm place to shepherd their children to adulthood. They imagined buying a house and teaching the kids to ride bicycles on land they owned.

Then came the limp. Mary noticed James dragging his feet; his gait was slowing. Lou Gehrig’s disease followed. With a diagnosis in hand, there was little money left to save and little hope to find a home.

The upside? They already had one — on Dartmouth Street.

By the late 1960s, Mary’s husband had died. Her widowed aunt lived there alone, battling both Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis. Catherine “didn’t have anyone else, and we didn’t have anywhere else,” Mary said. “So there we went.” She moved her family into the upstairs unit and shuffled between homemaking and medical aid, leaving her little time to think about if, or how, the community outside her window was changing.

Yet changing, it was. The promise of homeownership had started to fade a little in 1970. The gap between rich and poor — diminished by a stretch of broad prosperity — was deepening again. It became difficult to build housing as towns rewrote zoning laws to block denser developments, including the prototypical Boston multifamily like the one the Kevilles bought 30 years earlier.

Once Mary was a widow in her 40s, the street of humble homes where she lived had become a pot of real estate gold. She could never buy there — or anywhere else — on her salary as a secretary at a local dry cleaning company. So her Aunt Catherine sold her the Dartmouth Street homestead in 1976 as an early inheritance before she died. At the time, the median single-family home in the Northeast cost $47,300.

Mary paid a dollar.

Advertisement

The younger Mary — at least as her children remember — was curt and stern, devoted to St. Aidan’s Church in Brookline. She wore dark eyeliner under a sweep of silver eyeshadow and stashed a nip of Fireball in her purse. Mary never had much money, though she detested sharing her money troubles with her brood.

In the ‘70s, she splurged to add a chain-link fence and driveway to Dartmouth Street, all the family could afford. Otherwise, Mary’s front desk job was just enough to cover food and Catholic school tuition, and her kids already shared a bedroom and a makeshift attic that roasted without air conditioning. Despite the $55 rent Mary received from the downstairs tenant, mortgage payments she assumed from Catherine fell to the wayside.

The Logues once almost lost the house to foreclosure, until a neighborhood lawyer stepped in to help them fend it off.

“And thank heavens he did,” Mary said.

That saved the home where the family rested their heads and set them up to benefit immensely when the Boston market took off in the 1980s. The decade brought a record-breaking surge in home prices, including an uptick of 20 percent in 1985 alone, despite interest rates in the double-digits.

Had Mary sold the Dartmouth Street home, she would’ve walked away with a hefty profit. But that never crossed her mind. It was home. At various times, its ground floor apartment housed each of her adult children, by then prospective homebuyers themselves grappling with a market that tightened by the day.

Soon enough, they realized they might have to win the lottery, literally, to afford homeownership.

Her only daughter did just that. She lived downstairs at Dartmouth Street before she won Megabucks in 1989 and put a chunk of the winnings toward a house in Acton.

The oldest, Bill, served with the Army until he left to be a Watertown cop. The pay was decent. At 25, he managed to purchase a condo along the Mass Pike in Brighton for $40,000 and married a teacher he had met years earlier, while bagging groceries at Star Market. Four years later, a veterans affairs mortgage helped the couple move to West Watertown. It was “a heck of a house,” Bill said, “with a corner lot and a 16-by-9-foot living room and gum-wood molding.” In 1994, seeking better schools for their kids, they graduated to a four-bedroom in Belmont.

Buying never felt easy, said Bill, now 63 and retired. But it was attainable: His homes appreciated in value. He could always secure a mortgage after selling the older place, especially with the benefits afforded to veterans. And Bill was driven relentlessly by the spirit of immigrant children. “What do they tell you? Buy, buy, buy,” he added. “Own something. Build your wealth.”

But what would he tell his grandkids? Does the path Bill walked still exist, he wonders? Or is Greater Boston beyond the aspirations of the middle class?

A unit in his former Brighton condo building sold last year for $425,000. Real estate website Redfin estimates his old house in Watertown is now worth $1.4 million.

“It’s sad, but a part of nature in some ways,” Bill said. “People used to understand that you have to get the next generation prepped. Let them build up and out. Do we still believe that?”

Mary’s youngest son, James Jr., and his wife, Patty, live with that question daily. They moved into Dartmouth Street with their four kids in the 1980s, happy for the stability the home provided. James Jr. — a Watertown maintenance employee — made enough to get by on one full-time income, but not enough to afford a down payment anywhere like Watertown. They considered venturing out, but Mary only charged her son a few hundred dollars a month.

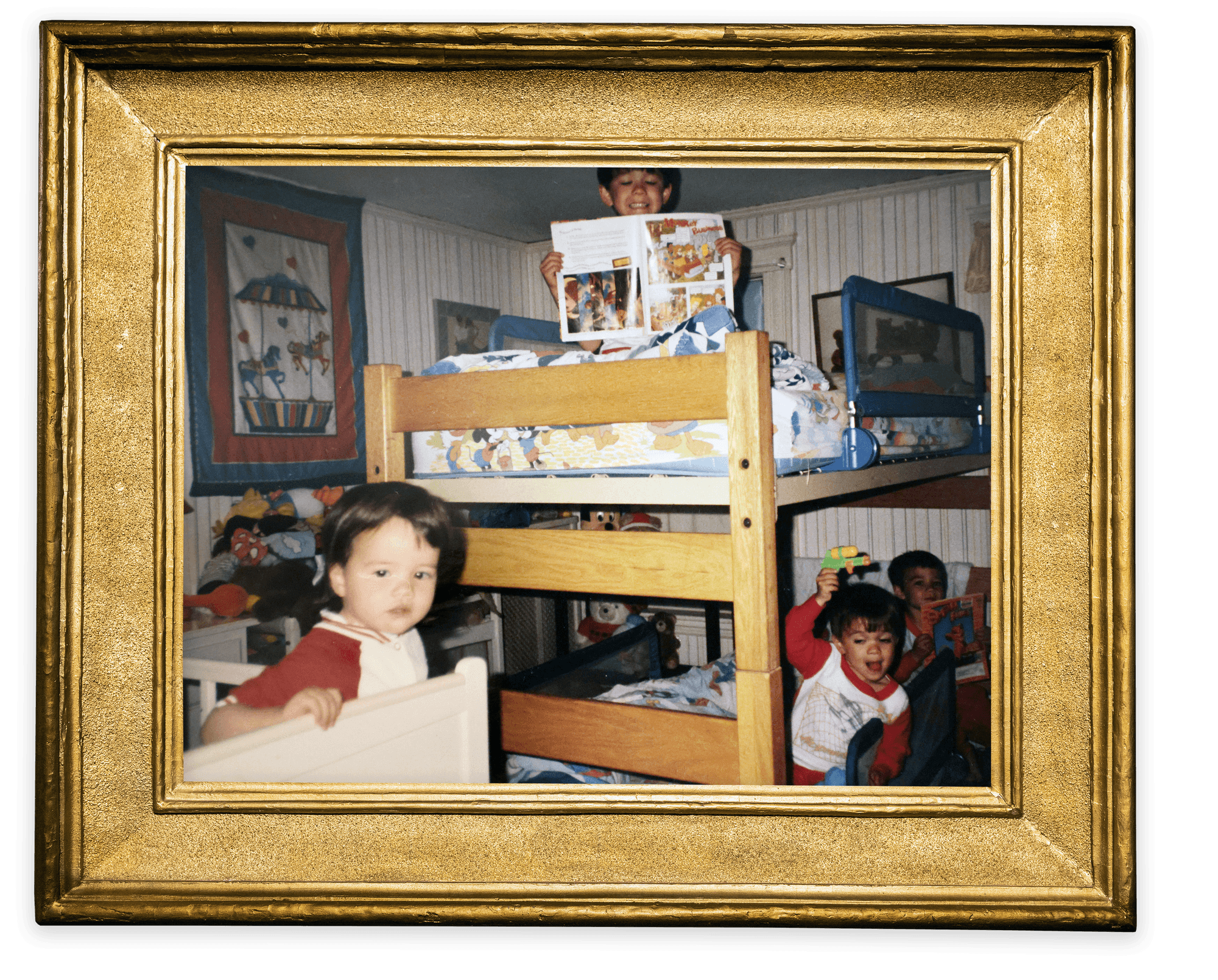

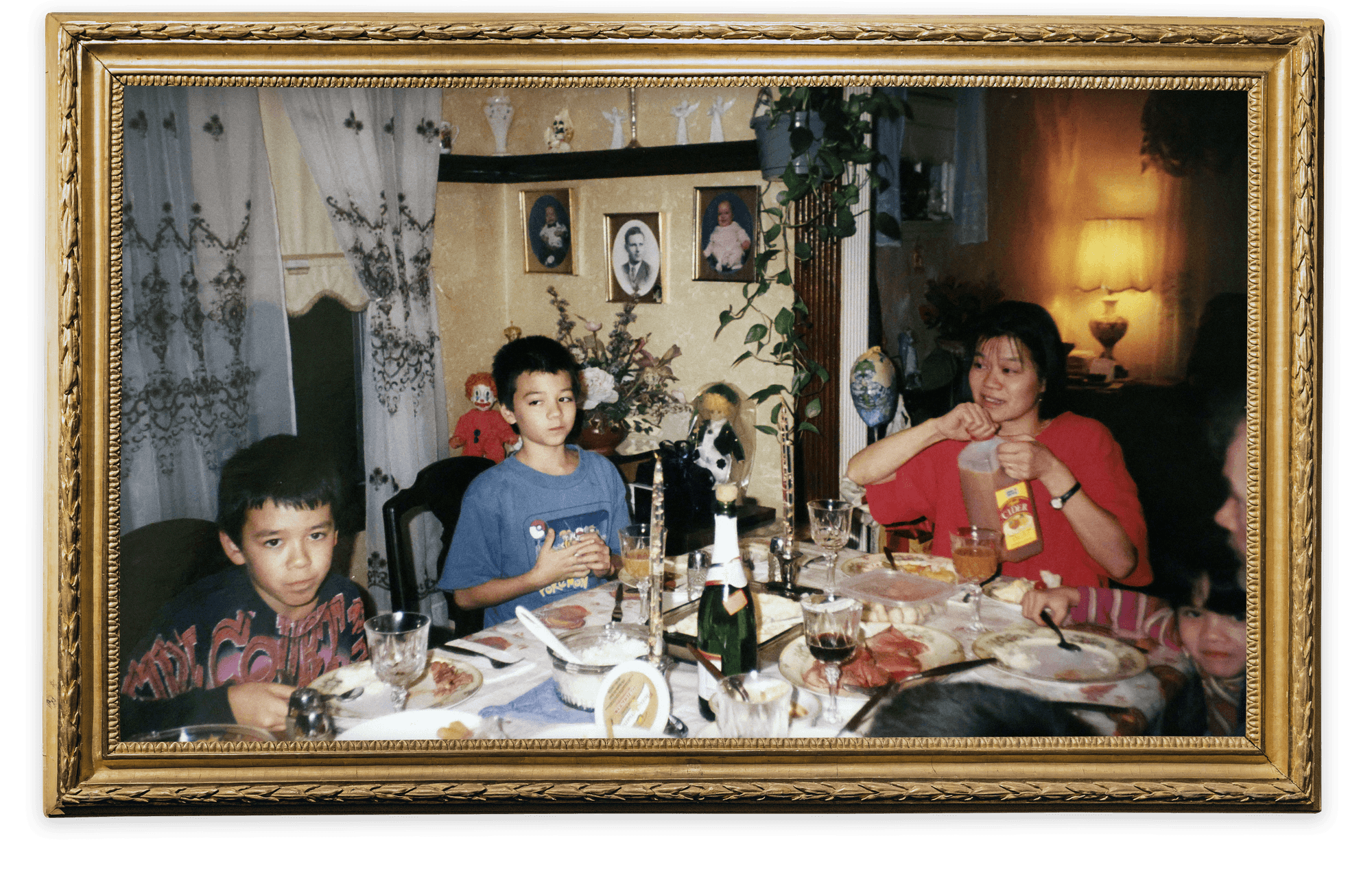

So the couple stayed: Their children grew up in a narrow second room with Mickey Mouse toys and oak bunk beds, jumping from the top level into a fortress of pillows below. On summer Saturdays, they ate Armenian pizzas called lahmajoun, adopted some of the basics of Chinese culture from their mother, and played Wiffle Ball on the cracked concrete street.

Patty worked part time at Bradlees to help with the bills, getting home by the end of school to steer the family through a typical Boston childhood. On the T, she whisked the kids to Fenway Park or the New England Aquarium. Their teen years were spent at the nearby Watertown and Arsenal malls, wasting time at the Dream Machine and Papa Gino’s.

The right time to move just never came.

“We thought living at the house was just going to be temporary,” Patty said.

Now it’s been almost 40 years.

Advertisement

Justin Logue — one of Mary’s grandchildren — entered an adult world with a housing market already stacked against him. He attended classes and participated in track at Bridgewater State in 2008, when that market crashed. Before he could legally drink, a firestorm of foreclosures had ravaged the country. Talk of layoffs, evictions, and a “Great Recession” filled the air.

It was a downturn fueled partly by the dream of homeownership, by banks writing mortgages that borrowers could not afford, on the theory that home prices would only rise. When they did not, things fell apart. Homebuilding plunged just as a demographic bulge of millennials hit prime buying years. Banks tightened lending standards. Places like Boston, spared the worst of the downturn, still saw buying become tougher.

Mary’s grandchildren fit squarely into that timeline. As they reached their 20s, Boston was quickly becoming bigger, better, and more expensive. The price of local homes doubled between 2009 and 2022. Drug companies planted themselves in Watertown, seeking what one biotech executive described as “the Kendall Square lifestyle at half the price.” Part of that prediction delivered. The curvy stretch along the Charles River where cast iron guns were once built now houses gleaming laboratories and brick townhomes. But housing prices rival Cambridge. This summer, the cheapest East Watertown home listed for sale on Zillow was $949,000. The new apartment buildings along Arsenal Street command $3,500 a month for a one-bedroom.

“I get it — Boston is a city filled with opportunities,” said Justin, 34 and an IT employee at a tech company. “But there’s a side of me that feels sad because I don’t think I can afford a home anywhere near where I grew up. … If it’s not going to get better, should I be buying now? Am I being smart about it by waiting until I feel ready? Or am I being dumb by making the timeline longer and longer, pushing the goal away?”

The only Logues who found a way to homeownership made great sacrifices, or had help.

Take Bill’s kids, for example. A homeowner himself, he helped his two children gain a foothold as best he could. His daughter lived with him for three years rent-free while saving for the down payment to buy a $417,500 house in Waltham in 2013. Mike, his son, also leaned on the parents for part of the closing costs in 2015.

Even a decade earlier, when the real estate market was more reasonable, buying felt brutal. Mike suffered through a year of open houses and negotiations and “sorrys.” “You don’t think other people will beat you out that quickly, with that much money,” he said. “But they do. It’s a defeating feeling.”

James Jr. — who still lives on Dartmouth Street — also offered his children the chance to stay in the old homestead as adults. In the past decade, they’ve each moved back to their childhood bedroom or the attic two floors above, putting aside money that would otherwise cover rent. But that was scarcely enough. Only one of four kids, James III, owns a home now.

With thick-rimmed glasses and spikey hair, he is the saver of the bunch, the pragmatist. James skipped college to go directly to work installing HVAC systems and managed to scrape together enough to buy a fixer-upper three-decker in Lynn for $435,000 in 2016. That was only the beginning of years of renovation work that included gutting the third floor, installing closets, and repainting bedrooms.

Now James keeps a half dozen tenants — friends and family scattered across the three floors, all paying well below market rent. He has stability, though he traded an easygoing chunk of his 20s for it.

“My choices have always been dictated by money,” the younger James said. “My life has been dictated by money.”

His three siblings also have good jobs in technology or pharmaceuticals, but few homebuying prospects. Brendan lives at James’s place in Lynn for $450 a month. Amanda moved out of Dartmouth Street last fall and rents in Cambridge. Justin lives with his wife in a $2,000-a-month two-bedroom in East Watertown. High school sweethearts, they’d rather buy and put down roots. But when the median sale price in Watertown sits at $900,000 — more than five times their household income — what are the options?

“We are already living at the lowest budget possible,” Justin said. “There’s not much room to cut anywhere else.”

Advertisement

Ask the Logue grandchildren what can be done to fix the housing crisis, and some degree of existentialism surfaces. One believes he’ll buy one day. Another just shrugs. (“I’ll see when I can, or if I can,” she said.) Only James III, the Lynn homeowner, speaks like a modern-day Robin Hood. “The answer is: Don’t be greedy,” he said. “The rent is too high to begin with for everybody. The only way that changes is if we act as a community.”

In a sense, that’s what the modern-day Logue clan is doing to preserve what they have and cannot stand to lose: the Dartmouth Street home that cocooned them from the market for nearly a century. A handful of family members pitch in each month to make payments on the mortgage and a decades-old loan for renovations. Handier relatives chop trees in the yard or update a bathroom.

Selling the place would fetch a princely sum. But they intend to keep it, for whomever can carry the deed forward in the Logue name. They would have to be willing to repaint the chipping exterior and replace the softening wood on the back patio. Still, Mary’s grandchildren hope, wait, and watch their hometown morph into something more beautiful than they remember, but where they cannot afford to stay.

Justin is coming to terms with the fact that there may be no future for him and his wife other than to move away from Watertown — maybe to Lowell, where you can still buy for around $400,000. He wonders if the powers-that-be consider the people the Greater Boston housing market is pushing away. He wonders what it will be like for the next generation: his cousins’ children, the baby he and wife are expecting.

Sometimes Justin asks aloud: “Does Massachusetts even care?”

The answer feels like no.

Diti Kohli can be reached at [email protected]. Feedback and tips can also be sent to the Boston Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected], or by calling 617-929-7483. Mail can be sent to Spotlight Team, the Boston Globe, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

Beyond the gilded gate

People in and around Boston are being challenged, in ways never before, to address the region's unprecedented housing crisis. The Globe Spotlight Team probed this question and found yet another crisis: One of consensus and will.

Preview: Data

Graphics: Why it’s so hard to afford housing in Boston

Part 1: Milton

In towns like Milton, home prices are a threat to prosperity. But they don’t have to be

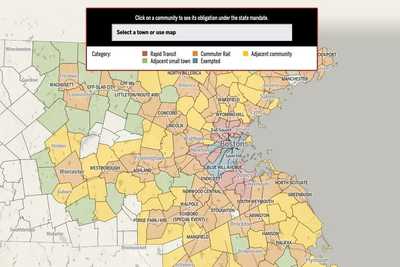

Map

How will the state’s historic rezoning mandate affect your community?

Part 2: Generations

One house, one family, and the fading dream of homeownership

Part 3: Luxury towers

Reckoning with Boston’s towers of wealth

Part 4: Brookline

An identity crisis comes to Brookline

Part 5: Single-family zoning

Reimagining an American ideal

Part 6: The renters

A Boston building, scattered souls, and rent control revisited

Part 7: Construction costs

The $600,000 problem. Why does it cost so much to build housing in Boston, and what can we do about it?

Calculator: Construction costs

Calculator: Penciling out a project

Credits

- Reporters: Mark Arsenault, Andrew Brinker, Catherine Carlock, Stephanie Ebbert, Diti Kohli and Rebecca Ostriker

- Editors: Patricia Wen, Tim Logan, Mark Morrow

- Photographers: Lane Turner, Jessica Rinaldi, Erin Clark, Craig F. Walker, Pat Greenhouse, David L. Ryan, Jonathan Wiggs

- Photo editors: Leanne Burden Seidel and Bill Greene

- Video producers: Olivia Yarvis, Randy Vazquez, and Dominic Smith

- Video director: Anush Elbakyan

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development, graphics, and data analysis: Daigo Fujiwara

- Development: John Hancock, Andrew Nguyen

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanac and Jenna Reyes

- SEO: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2024 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC