BEYOND THE

GILDED GATE

Greater Boston has a housing crisis, but doesn’t act like it. In towns like Milton, soaring home prices are a barrier to a new generation of buyers and a clear threat to future prosperity. It is a fact of life here, but it doesn’t have to be.

Milton

This is what subversion of the law looks like in an affluent Boston suburb.

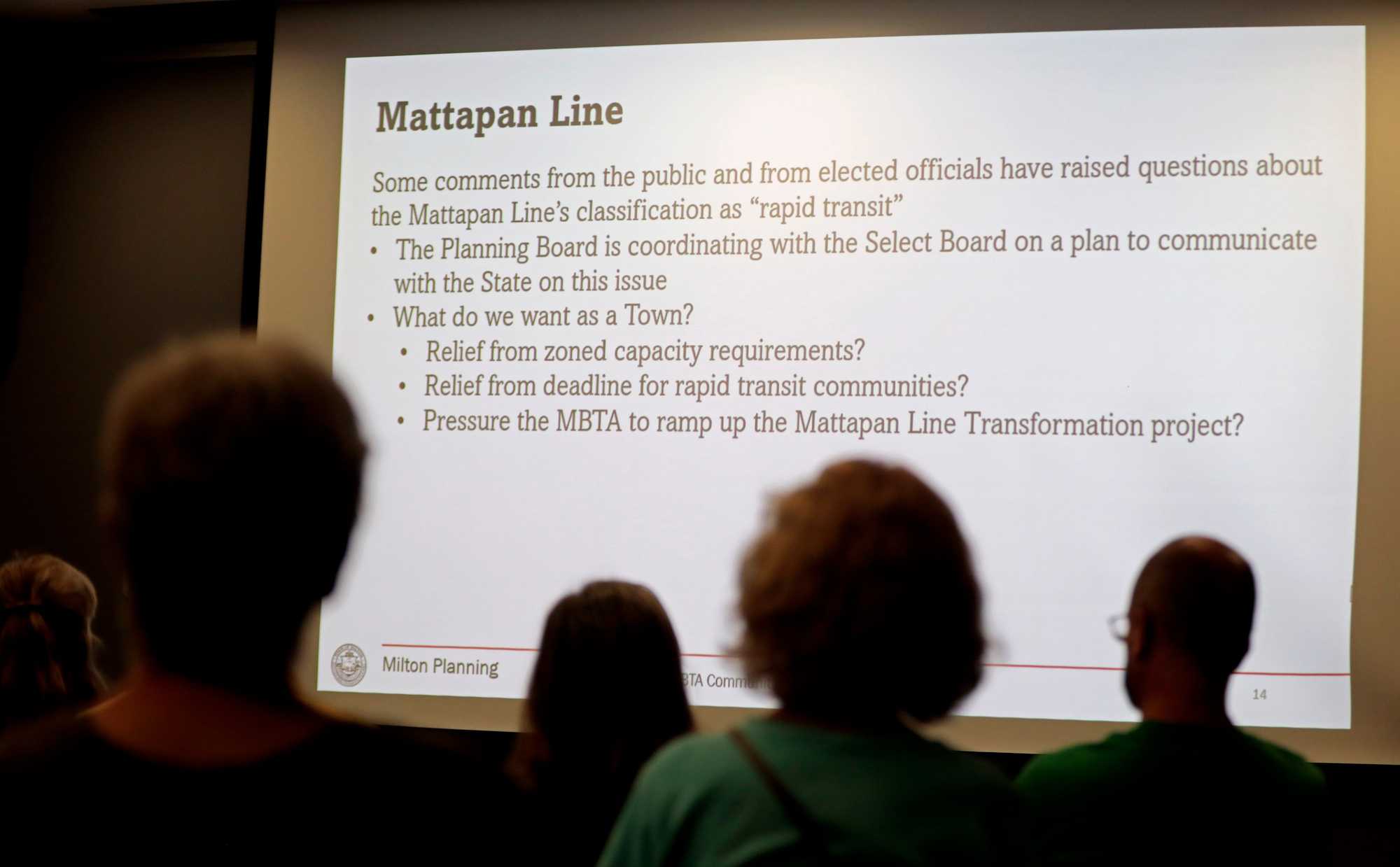

It is the town planner being buttonholed about Milton’s obligation to zone for more apartments and condos, as a historic new law requires of communities served by the MBTA: “Are we obligated to keep that T line?” a resident inquired, asking about the Mattapan Trolley. “For the grief it’s going to cost us, what if the residents voted to get rid of it?”

It is a disembodied voice in a public Zoom meeting that urges, “We need to step back and not talk about how we’re going to do this … but really whether we’re going to.”

And it is a retiree sitting through a 72-minute Planning Department slideshow on the town’s obligation to encourage more multifamily housing, and then rising to point out, “There’s no slide here for noncompliance.”

On one level, this quiet revolution, politely unfolding under Robert’s Rules of Order, is about local control, self-determination, and fear – fear that more permissive zoning required by state law would forever change this prosperous bedroom town of mostly single-family homes.

But really it is about much more than that. What is at stake is no less than the future of the region.

For Milton’s story is everywhere – it is the story of Boston’s pricey suburbs, cocooned by restrictive single-family zoning rules that make apartment and condo projects so hard to permit that they are rarely built.

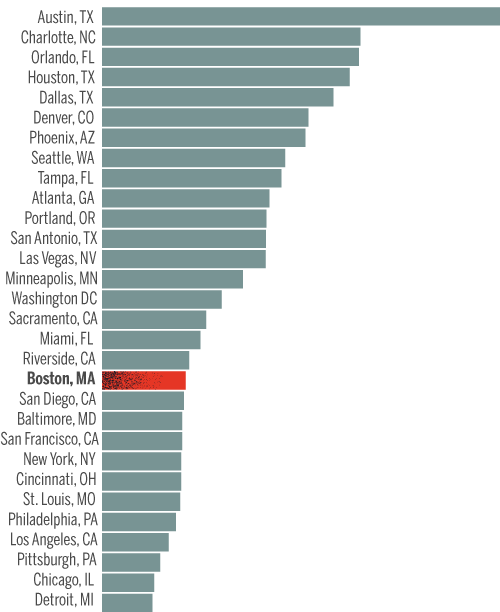

It is the story of a town, and region, that has for half a century doubled down on the status quo, or made zoning even more restrictive, all but guaranteeing that single-family home prices — rising more steeply here than in any other state since 1980 — will remain shockingly high.

The fallout from these outrageous home prices is a sort of economic climate change, steadily making much of the region uninhabitable for those of modest incomes. Expensive housing acts as a golden gate, and there is a price to be paid for living in a gated community.

This is the price: Across this region, the dream of suburban life is largely foreclosed by lack of affordable options to the children of those who live in the suburbs now, to the town employees who keep municipalities humming, to newcomers who might bring new energies to town — and added diversity of class and race.

There are not nearly enough homes being built around Boston to keep up with the young but maturing generations looking to buy, and the people coming to fill new jobs created by the lively tech economy. The region creates about three jobs for every one new home these days — a ruinous ratio that is sure, in time, to choke off the prosperity that has prevailed here for so long. Indeed, there are signs that it already is.

With an abundance of data showing a housing shortage this acute and damaging, the Boston Globe Spotlight Team decided this year to study the roots of one of the most intractable problems facing our state, and to examine some possible solutions. The team’s findings will be shared in a series of stories that begins today.

One fact became obvious in the course of this review: The sense of urgency here does not match this brewing crisis. Not even close.

One reason may be that swelling property values don’t feel like a crisis for those who bought into the market years or decades ago, they feel like a windfall. This region, Milton included, is awash in paper millionaires.

But standing pat will suffocate hope — the hope of many now trying to enter this mad housing market, from empty-nesters hoping to downsize in the town they know, to newcomers seeking to buy a first home as careers and prosperity grow.

They are the new neighbors, so to say, that Milton, and other desirable suburbs, may never know.

How did it come to this? And what can be done?

Among those feeling outside the gate are Tara Gregory, 53, of Hyde Park, and her mother, Brenda, 72, who have just about given up on moving to Milton after more than two years of visiting open houses and scouring home listings. The town, so tidy and green with a sense of community, reminds Brenda of growing up in North Carolina. “It makes her feel like down South,” said Gregory, who works for a day care center. “She’s open, but her dream place is Milton.”

“The good properties are really high,” she continued. “That’s where my mom really wanted to be, but we recently started looking in other towns because our chances in Milton seem so slim to us.”

Inside the gate and happy to be there is 80-year-old Paul Vaughan, who made it to Milton more than half a century ago. He is the one who asked the town planner whether Milton could elude the new zoning rules by renouncing its transit line. A retired private investigator, Vaughan is protective of his town, he says, because, well, it’s special. In the late 1940s, when Vaughan was a boy growing up in Dorchester, his big Irish family — “cousins by the dozens” — would caravan together to beach days at Nantasket or in Duxbury, sometimes passing through Milton on the way.

Vaughan recalls his grandma raving about Milton in her Irish brogue: “Oh, bejesus, isn’t this beautiful?” Vaughan moved to town in 1967. He felt like the lucky Dorchester kid who’d made it.

His story taps into a fear about the state-mandated rezoning that ricocheted around Milton and the wider region this past summer: If you build bigger, higher, denser, you’re building something like the housing in much of Boston, and not everybody wants to live in Boston. It is an emotional issue. In Arlington, for example, residents who did not have a chance to speak at a September public meeting on the state-ordered zoning changes raised such a ruckus that officials called for the police to restore order.

Massachusetts home builders have been warning about the stifling effect of local building restrictions for 60 years. Home construction fell off a cliff in the 1990s, the least productive decade for new homes in the state since the 1920s, when free spirits danced the Charleston at speakeasies and the state’s population was little more than half what it is now.

“If you go 20 or 30 years producing a fraction of the new housing that you used to produce, you create an enormous collision between availability and affordability,” said former governor Charlie Baker, who signed the ambitious 2021 state law requiring Milton and other towns in the MBTA service area to create and approve new zoning rules that encourage multifamily housing. The first wave of deadlines for action on the new rules is fast approaching at the end of this year.

The point of the law is to increase housing supply to meet a ravenous demand that’s driving up prices. The median selling price for single-family homes in Greater Boston hit a record high of $910,000 in July, with Milton at $928,000. To afford those prices, a household would need an annual income of at least $300,000, according to Daniel McCue, a senior research associate at Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, factoring in mortgage and other costs. That’s nearly three times the household median income in the broader Boston metro area, which is $104,000.

Taming this problem is one of the greatest challenges of our time. The housing crisis endangers what makes this region so desirable — the workers who are the beating heart of the universities, hospitals, and drug makers that have transformed metro Boston into the Silicon Valley of biotech. Without housing they can afford, these workers will not come here or stay here, employers will not expand here, and a noose around our economy tightens.

Advertisement

Character of a town

Though it borders the city, Milton still largely feels like a typical town. It’s a bedroom community where the few commercial properties are tucked into village retail hubs. Some of its neighborhoods are grids of closely nestled middle-class homes, others look more like sections of a rural village than a suburb on Boston’s southern edge. The town population of 28,630 has barely increased in 50 years. You can still get lost on winding roads and come across horseback riders on Hillside Street. The WWII-era cars of the Mattapan Trolley are working artifacts from a long-distant past.

Yet Milton is not trapped in time. The town borders neighborhoods with sizable Black populations, Mattapan and Dorchester, and Milton is home to a growing Black middle class; Black residents make up about 17 percent of the population, a ten-fold increase since 1980. Sixty-percent of the Black residents of Milton are concentrated in a census tract in the northwest part of town that borders Mattapan, according to a 2022 report by the town’s Equity and Justice for All Advisory Committee.

The town has also grown more politically liberal over the past generation. Its voters favored Republicans Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and Milton’s hometown president, George H.W. Bush, who was born there in 1924. But since Bush won the town in 1988, Milton has supported Democrats for president, generally by widening margins. Joe Biden won here by 48 points in 2020.

It is a community of fine homes, abundant lawns, and woods, with a scattering of gently aging mansions. People here are understandably proud of their way of life. Many don’t want to see it change, and don’t want to lose their say in how Milton is developed.

“Some see it as a Brigadoon,” said Kathleen O’Donnell, of East Milton, a real estate lawyer and member of the town’s Zoning Board, conjuring the image of a mythical community untouched by modernity. She did not intend it as a compliment, for it implies an inability to adapt.

As in many affluent suburbs around Boston, generations have risen up like an immune response to defend the town from certain proposed developments, especially those that would add multifamily housing.

If you go 20 or 30 years producing a fraction of the new housing that you used to produce, you create an enormous collision between availability and affordability.—Former governor Charlie Baker

Home construction in Milton slowed dramatically after the 1960s — and all but froze the past two decades. About 93 percent of the town’s housing stock was built before 2000.

The overwhelming majority of Milton homes, about 78 percent, are single family. Apartment and condo buildings in Milton have been permitted on a case-by-case basis. The town has few renters: 82 percent of Milton’s housing is owner-occupied, 20 points higher than the statewide average.

Milton is also wealthier than most towns. Its median household income of $154,000 is well north of the Boston metro median of $104,000 and the statewide median of about $94,000, which itself is among the best in the nation.

O’Donnell, 71, now in her second stint on the Zoning Board, grew up outside New York City, studied at Boston College, and settled in Milton 38 years ago. She loves it; enough so that she believes the town should open itself up so people of differing incomes have the opportunity to live there. That would take some new types of housing.

In March 2022, O’Donnell, then an elected member of the Milton Planning Board, fought for a Town Meeting article to make it easier for Milton homeowners to build accessory dwelling units, the small homes tucked into existing house lots that are commonly known as granny flats. Like similar laws in force in California, the proposal would have granted more freedom for someone in a single-family district to turn a garage, carriage house, or some small structure into an apartment for a family member or for rent.

The political debate over the proposal “was just awful,” O’Donnell said. “People accused me of trying to ruin the town.” Some doors were shut in her face during her walk-and-knock reelection campaign that spring, she said.

“Everybody who complained said, ‘We left Dorchester to come to Milton and now you’re trying to turn Milton into Dorchester,” she said. “It was like, ‘We made it and who are you to come here and try to change our town?’ "

The accessory dwelling proposal was ultimately sent off for further study. O’Donnell lost her seat on the Planning Board in the April 2022 election, clearly, she said, over the issue.

Danya Raphael, a member of Milton’s Affordable Housing Trust, acknowledged that opponents of accessory dwelling units “campaigned a bit louder than we did.” She predicted, though, that the measure, and others, would eventually pass out of necessity, and noted that many people in Milton support the construction of more multifamily housing. “We have teachers, nurses, firefighters, and police officers that the town depends on who can��’t afford to live here,” she said. “I can’t see any argument that a healthy housing mix is not healthy for the town.”

For supporters of more housing opportunities in Milton, the failed fight over accessory dwellings was a missed opportunity, though not the worst one. The worst loss, the one they still talk about with head-shaking disbelief like it was the 1986 World Series, is what happened to the Governor Stoughton land.

William Stoughton, a Colonial-era governor and Milton landowner, is best known to history as chief justice of the Salem Witch Trials, not the proudest moment in Massachusetts jurisprudence. Upon his death in 1701, Stoughton bequeathed a 40-acre Milton woodlot to the town, specifically “for the benefit of the poor.” It became the site of the town farm, where indigent residents found shelter and work. Around 1941, buildings on the land were leased out and the proceeds deposited into a fund for Milton residents in financial need, according to Probate Court documents.

More than 300 years after the gift, 21st-century Milton was still wrestling with how to honor Stoughton’s wishes. Starting around 2008, a local committee researched ideas. Julie Creamer, a member of the committee studying what to do with the gift, pushed to use the land for affordable housing, something the town needs, she said, that was in concert with Stoughton’s wishes.

A nonprofit housing developer, The Community Builders Inc. of Boston, proposed building a neighborhood on the land with up to 100 units of mixed-income and affordable housing.

Instead, the selectboard, who are the trustees of the Governor Stoughton Trust, in 2011 sold most of the land for $5 million to Pulte Homes of New England, a high-end housing developer. The sale proceeds went into a fund, where the interest is to be used to help Milton residents in financial hardship.

Luxury homes have been built on the former Milton Town Farm site, most of which was sold to Pulte Homes, a high-end developer. The land had been bequeathed to Milton for "the poor" in 1701 by William Stoughton, a Colonial-era governor. On the portion of the Stoughton land that Milton kept, a boarded-up building decays beneath a tangle of nature. The parcel is also home to the town's animal shelter, which is being rebuilt elsewhere, potentially freeing up land for affordable housing. (photos by Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

On Milton’s former poor farm, Pulte built 23 very large, single-family homes, clustered in a neighborhood of homogenized affluence. Each house is worth close to $2 million, according to property records.

Multimillion dollar homes on land meant for the poor: “That was the biggest misstep the town has ever made,” Creamer said.

Former selectboard member Robert Sweeney, on the board at the time, said “the people who are critical of that decision are incorrect. The sale of that land benefitted the poor of Milton by the amount of $5 million.” Administrators of the trust “have done a wonderful job very quietly helping the poor of Milton” with essentials such as home fuel costs and transportation.

Milton kept about four acres of the Stoughton land. There is a push now within town government to open the land to bids by affordable housing developers, for perhaps 30-40 units. The plan has seen some twists and turns, explained Tim Czerwienski, Milton’s director of planning and community development, who also is deeply involved in Milton’s efforts to comply with the MBTA communities rezoning.

For one, the town’s outdated animal shelter is on the parcel. Initial construction bids to rebuild the shelter elsewhere were too high. Then, last April, an anonymous donor pledged $2.5 million toward a new animal shelter — on the condition that it be built on the current site. That perked the antenna of local housing advocates, who suspect that some wealthy neighbor offered the money to frustrate plans for affordable housing.

“For crying out loud,” said O’Donnell, unable to keep from laughing, “how obvious is that!”

The town ultimately received an affordable bid to build a new shelter, and in September approved a contract with Axis Construction to build at an alternate site, on the former dump access road off Randolph Avenue. Town officials plan to eventually solicit proposals from developers to erect affordable housing on the Stoughton land, though “it’s still very early days,” Czerwienski said.

Legacy of restrictions

New York City generally gets credit for the first comprehensive zoning plan, in 1916. The general idea was, let’s put business here and residential over there, so the different land uses don’t bother each other.

But from the very beginning, land rules were also ruthlessly deployed to exclude certain people.

In 1912, Massachusetts lawmakers passed the Tenement House Act for Towns, a law with links to the eugenics and anti-immigrant movements of the early 20th century, and which shaped the development of much of suburban Boston.

The Tenement House Act was not land use zoning, though it acted like zoning in one important way — it banned a popular style of multifamily construction, the classic New England triple-decker, home of so many of the working class and, critically, new immigrants. The law contained a “local option,” meaning it took effect only in communities that voted to accept it, generally at their town meetings.

Ostensibly a building code, the act provided rules for things such as ventilation and sanitation in apartment houses. But its most consequential paragraphs targeted apartment structures made of wood, prohibiting kitchens above the second floor and occupancy by more than two families. That killed the triple-decker.

It was no coincidence that the Tenement Act so directly targeted housing affordable for immigrants. The act was championed by a group called the Massachusetts Civic League, according to state records. The founder and main financial backer of the group was Joseph Lee, a wealthy Boston philanthropist, School Committee member, and anti-immigrant crusader.

The other major organization Lee financed during this period was the Immigration Restriction League, a group that lobbied to curb immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe, largely to keep out Jews and Italians.

“I believe in exclusion by race,” Lee summed up in a letter to a friend, according to The Guarded Gate, a 2019 book on the anti-immigrant movement by former New York Times public editor Daniel Okrent.

Lee’s Civic League attacked triple-deckers as “monstrosities” that destroy property values, breed disease “in darkness and filth,” and contain “a class of people who contribute little to the revenues of the city, while their presence increases the cost of all departments.”

Milton Town Meeting accepted the Tenement Act in 1913. Other Boston suburbs followed suit. Just two years later, a Boston Evening Transcript headline pronounced “The Passing of the Three Decker: Twenty-Three Massachusetts Towns Have Sounded Its Doom by the Adoption of the Tenement House Act.”

Over the next several years, through new state laws, municipalities amassed even greater power to control development. The state Constitutional Convention in 1918 supported an amendment affirming the constitutionality of land use zoning, despite concerns that zoning would be used to segregate classes or races. The state Legislature followed up with enabling legislation in 1920, and by the end of that year municipalities such as Brockton had approved land use zoning.

In 1937, Milton undertook a major zoning project, in response to reports that “several hundred” new, tiny house lots were soon to be proposed, according to news coverage at the time in The Milton Record. A committee produced a zoning plan to raise minimum lot sizes in developed areas and to control building in open areas by imposing lot minimums of up to 40,000 square feet, about one acre.

A local real estate association argued that the jump to 40,000-foot minimums for one house “is radical” and “excludes the average citizen.” But critics were lonely voices. In early 1938, Town Meeting voted 185-13 to approve the plan.

By 1960, such restrictive suburban zoning around Greater Boston began to drag on the construction of homes, and the term “housing crisis” emerged. Homebuilders sounded the klaxon, pouring out frustration at a conference in Boston in 1961, saying that many towns had zoned out mid-priced homes.

“So long as we have these outlandish requirements of one- and two-acre lots for new homes, there’s not much hope of keeping new home costs down,” the president of the Home Builders Association of Greater Boston said at the time.

Home building slowed significantly over the 1960s. In the 1950s, Massachusetts had produced about 290,000 new homes, increasing total housing stock by 20 percent, according to census figures. Only about 199,000 homes were built in the ‘60s. After a rebound in the 1970s and 80s, housing development fell way off in the 1990s, with only 149,000 new homes produced. The past two decades have not been much better, averaging 188,000, about two-thirds of what Massachusetts produced in the 1950s.

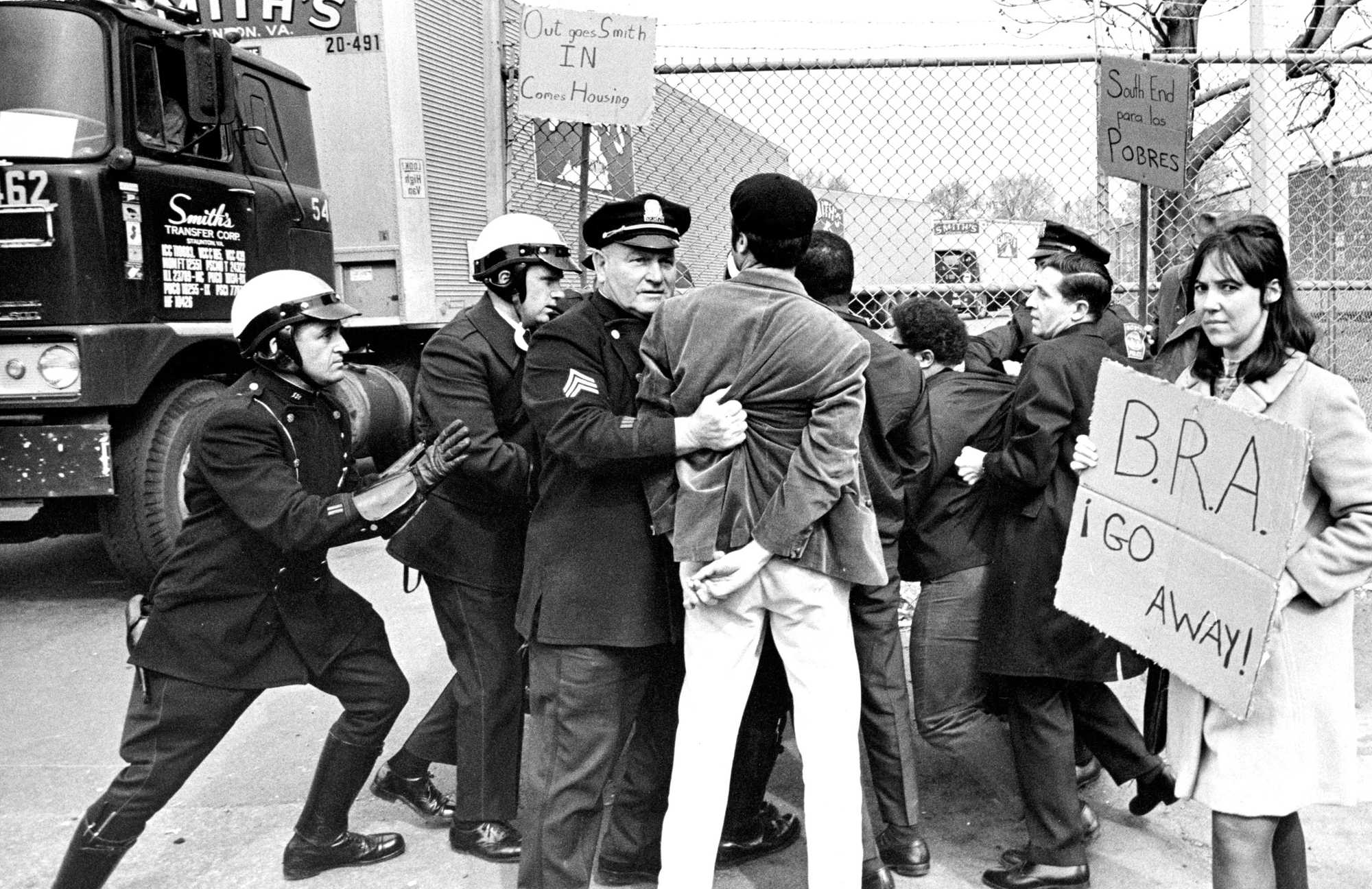

By the end of the 1960s, Greater Boston was feeling the shortage. Prices were rising. Low- and moderate-income families were being squeezed. It was a time of upheaval and high emotions over growing inequity, particularly in the city.

“We’re almost destitute for housing,” then-Boston Mayor Kevin White said in late 1968.

The Legislature responded. After spending the first half of the century granting power to local communities to control development, state lawmakers took some of that power away.

![Boston, MA - 11/1/1965: People protest housing redevelopment on Hefferan Street in the Brighton area of Boston in November 1965. Boston officially began an urban renewal program in 1964 that focused on physical and social redevelopment of lower income areas of Boston. It was met with resistance from many Boston-area residents. [Date unknown - estimated to month] (Bill Brett/Globe Staff) --- BGPA Reference: 141205_CB_014](/2023/10/special-projects/spotlight-boston-housing/static/dabde7ac9ed91c0ae5cd79b980c9d4c3/3555a/HJ6XTUPD2FCNLF56755J5VLYXY.jpg)

Housing has long been an emotional issue. At left, people protested housing redevelopment on Hefferan Street in the Allston-Brighton section of Boston in November 1965. At right, Boston Police move protesters so trucks can go at the Smith Transfer Corp. on Tremont Street in Roxbury in April 1968. Anti-urban renewal demonstrators were picketing the terminal, demanding that Lenox Street apartments be renovated rather than demolished. (Bill Brett, Ollie Noonan Jr./Globe Staff)

In 1969, lawmakers debated a bill to allow developers to overcome zoning in communities that fail to maintain 10 percent of their housing stock as income-restricted affordable homes. Opponents blasted the legislation as “the death knell of local government.” One suburban representative argued that the bill “would transport segments of the ghetto to the suburbs.”

On the other side, a lawmaker argued that “artificial zoning barriers” to the production of new homes were “morally indefensible.” The bill passed in August 1969. It came to be known as Chapter 40B, for where it appears in the General Laws. The law has facilitated multifamily developments that would not otherwise have been built, but it’s hard to call it an unmitigated success, given that 78 percent of municipalities remain below the 10 percent affordable housing threshold.

Milton’s subsidized housing inventory is at about 5.6 percent, according to data provided by the town. About 90 percent of the town’s subsidized housing is for seniors, data show, which some housing analysts see as a common sign of suburbs being unwelcoming to young families, especially those who might add burdens to the school system.

Nearly 20 years after 40B passed, in a major rezoning in 1988, Milton increased minimum lot sizes in large areas of town to two acres, according to the planning office.

Over the decades, these building restrictions have reduced the variety of housing in Milton. “The housing we have allowed under our zoning is big and definitionally expensive,” Czerwienski said. Developers generally don’t build starter homes on two-acre lots. In addition to pricing out people who want to move to town, expensive real estate traps Milton residents who want to downsize their homes without leaving the community they love.

People such as Deborah Azerrad, a graphic designer, who moved to Milton 23 years ago from Brookline to raise a young family. Now 60, she is single and in more house than she needs. “I would like to stay in my community where I am now, but just in a smaller place,” she said. But it is hard to downsize in a community lacking a variety of lower-priced housing options. “There is nowhere for me to move that’s affordable to me.”

Advertisement

Taking back power

Baker, as governor, got a piercing look at housing’s stranglehold on the economy, in 2017, when retail giant Amazon conducted a national search for a city in which to build a second headquarters to base thousands of jobs. Top state leaders lobbied hard to woo the company.

“We were one of the five finalists, right?” Baker recalled. “[Amazon officials] came and visited us in 2017, somewhere around there. Jay Ash was still the secretary of Housing and Economic Development, and he said to me, ‘This housing thing is killing us.’ And I said, ‘What do you mean?’ He said, ‘Our housing prices are high, but more importantly, they’ve done their homework on how hard it is to produce more housing. And I think that’s gonna do us in.’

“And by the way – it did,” Baker said.

Amazon passed on Boston for New York and suburban Washington, D.C.

To facilitate more home building, Baker proposed, among other ideas, to amend state law so that an array of municipal zoning changes and exceptions would be approved on a straight majority vote of a town meeting or a municipal board, rather than a two-thirds vote. The proposal was tucked into an economic development bill passed in 2020, to which the Legislature also added the more controversial MBTA communities requirement focused on multifamily housing.

The MBTA provision requires 177 cities and towns in the T’s service area to approve new zoning to permit dense environmentally friendly multifamily housing, largely around T stations, so residents can easily commute by train. The intention is to encourage more housing construction while trying not to exacerbate the region’s other hellish problem – commuter traffic.

Under the law, Milton must rezone to permit 2,461 units, which represents 25 percent of the current number of year-round homes in town. A fact easily lost when the rhetoric heats up is that all these new units are theoretical. The mandate is to rezone, not build. The law presumes the invisible hand of the free market will ultimately erect housing within the more permissive zoning.

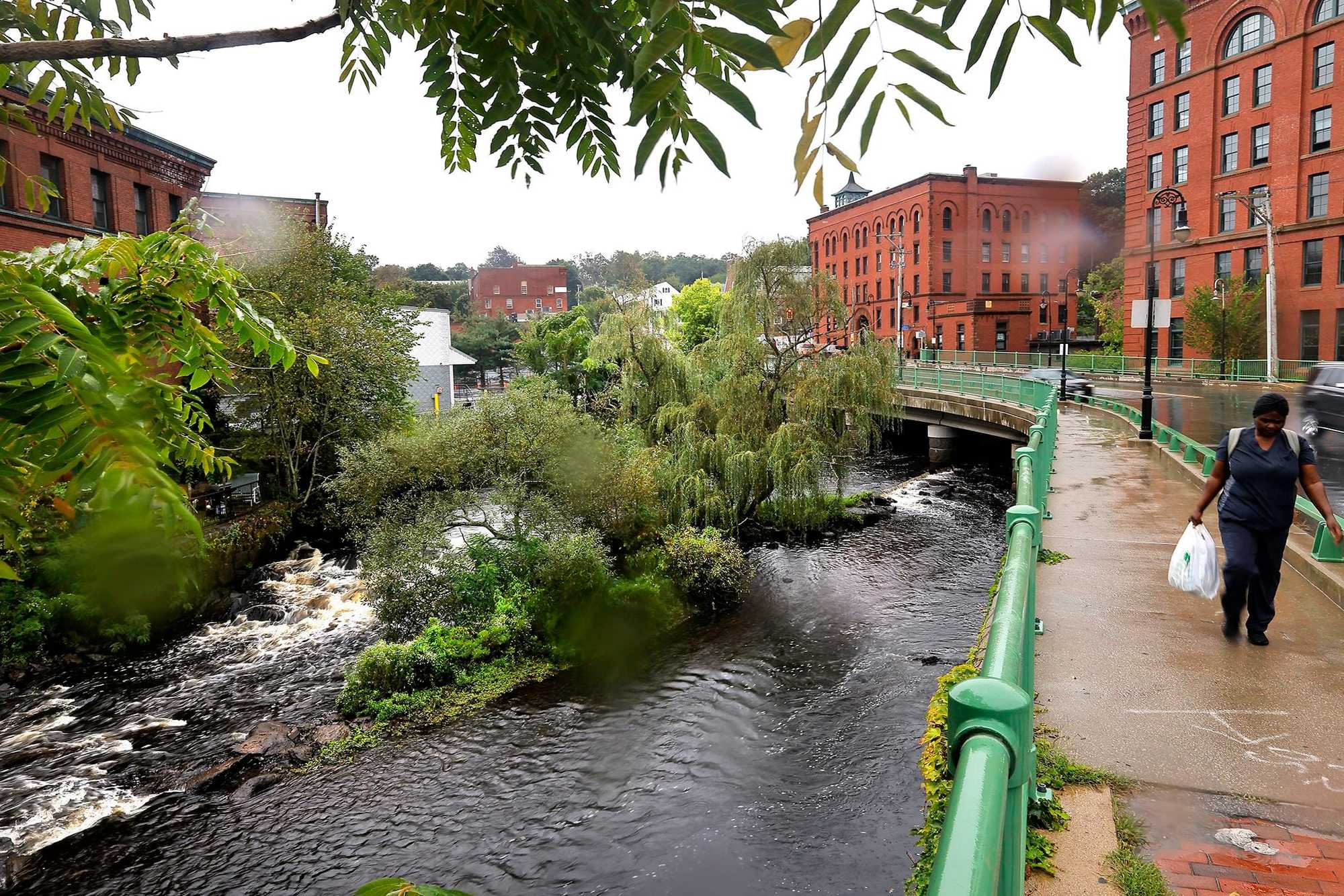

The Hendries condo development is adjacent to a Mattapan Trolley stop in Milton, exactly the kind of housing the state is encouraging with its new zoning mandate. At right, a pedestrian crossed the Adams Street Bridge that connects Milton and Dorchester. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

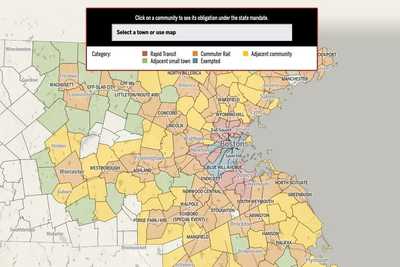

Milton is among a dozen communities serviced by MBTA “rapid transit” — the Red, Green, Blue, Orange, and Silver lines — facing a deadline to rezone by the end of this year. Next year, commuter rail and adjacent communities must rezone; in 2025, adjacent small towns.

Towns and cities that refuse lose access to certain state grants. The bigger deterrent is the threat of litigation brought by the attorney general. In August, a housing advocacy group sued the Town of Holden for not completing initial rezoning forms. Holden’s town manager told the Worcester Telegram and Gazette in March, “Arbitrary borders drawn by Boston politicians to change our zoning is something we’re not going to go along with.”

Map: How will the state’s rezoning mandate affect your community?

Click on a community to see its obligation under the state mandate.

Pushback against the mandate from across the region should not be a surprise. People around here don’t like being bigfooted by big government, and usurping local control over development is an unusually aggressive move by the state.

On a scorching day this past summer, Brian O’Halloran, 68, of Milton, a retired software engineer who worked in Boston, gazed across the street to the splendid single-family homes of his neighbors, and spoke about his fears. Under more permissive zoning, a developer with dollar signs in his eyes might one day buy up those single-family houses, raze them to their cellars and, without public hearings or a vote from Town Meeting, erect an apartment building that could alter life forever on O’Halloran’s hushed dead-end street.

For someone so politically engaged — O’Halloran is a Town Meeting member — not having a say about a major neighborhood development would be hard to swallow. Voters would lose their voice.

Not far from O’Halloran’s street, workers this summer were completing interior construction at a new 38-unit condo building at the site of the former Hendries ice cream factory, which was approved after many public meetings and with input from the community. “Whatever people think about this building,” he said, “it went through the bottom-up process. The decision was that it would be a good thing for the town. Others may say it won’t be, but at the end of the day we all got a chance to say our piece.”

The prospect of losing that voice leaves him with “somewhat the fear of the unknown,” acknowledged O’Halloran. That fear is why he and others in Milton have raised the notion of the town not complying with the rezoning requirement. And if the town gets sued, well, let’s see what the courts say.

Baker said he appreciates the gravity of taking power from municipalities and local voters. He is a former selectboard member in Swampscott. “We have a deeply embedded commitment to local control,” he said. “I mean, we had local communities before we had a state.”

The uncomfortable distance that Baker and the Legislature were willing to push the towns in the name of more homes is another indication of the magnitude of the crisis.

Put simply, Baker said, “We need the housing.”

‘My success is from having a place to live’

Two diverging philosophies divide Milton residents, said Milton lawyer and affordable housing activist Linda Champion.

“One is, ‘Don’t come to Milton unless you can afford to be here,’ " Champion said. “The other is, ‘We want more people to come because we all benefit from [economically and racially] diverse people coming here.’ "

Champion backs the rezoning and says there is significant grass-roots support across town for permitting more multifamily housing. She is on the steering committee of Affordable Inclusive Milton, a newish citizens group that advocates for more affordable homes and for diversifying Milton’s population. The group sponsored an early public informational forum on the MBTA communities law.

Champion, 50, has lived in Milton for 22 years, having moved here from Canton. She left Texas as a teenager to reconnect with family in Massachusetts. That didn’t go as she hoped, but Champion stayed, trying to make a living as a woman of color alone in a place she didn’t know, working modest-paying jobs. Housing was always a top concern. She lived in a coworker’s spare room, and then with strangers who needed a roommate. It was unsettling and stressful.

By 1991, however, she secured a subsidized studio apartment in Boston. Her rent was based on a percentage of her income. It was her first housing that was stable and reasonably priced, and “it changed my life,” she said.

She worked as a secretary by day, went to college in the evening, and then to a second job as a legal transcriptionist. She got her undergraduate degree at Suffolk University, and then went to Suffolk Law. Now she is a prosecutor for the Suffolk district attorney’s office and a professor at New England Law.

Having a dependable, safe, affordable home “allowed me to go to school and then to college and then law school,” Champion said. “My success is from having a place to live.”

Advertisement

‘This is the rule now’

Czerwienski, the Milton town planner, came from New Jersey to Boston College as an undergrad in 2002, got his life wrapped up in Greater Boston, and stayed. After grad school, he worked as assistant planner in Milton, then as a project manager for the Boston Planning & Development Agency, before coming back to Milton as planner in 2020.

That is how Czerwienski became the public face of Milton’s massive rezoning effort this year.

Czerwienski is 39. He wears the sculpted beard of an English professor and can speak extemporaneously about land use policy seemingly without end. He has the even keel of someone who understands that local government is a customer service business. It was Czerwienski who fielded the eye-popping question about avoiding the rezoning by getting rid of the trains, to which he answered mildly, “That would not be my advice to the town of Milton.”

Tim Czerwienski, director of planning and community development for Milton, leads a public informational meeting on the MBTA communities requirement, in the Milton Public Library in June. (Pat Greenhouse/Globe Staff)

At a residents’ meeting in May, Czerwienski fielded a question about why Milton isn’t pushing back harder against the state’s demands. A member of the town’s elected Planning Board, Sean Fahy, jumped in to defend Czerwienski. It’s Tim’s job to do all this work, Fahy explained, but “it’s not a foregone conclusion” that Milton will comply. “Town Meeting will determine whether or not we have made the decision.”

“Thank you for that, Sean,” Czerwienski said. “And, you know, I’m – my job is to be a rule follower. And this is the rule now.”

While Czerwienski, the planning staff, and consultants spent the summer and fall working with the Planning Board on new zoning, the board also explored another path.

The Mattapan Trolley, the reason Milton is classified as a rapid transit community, is unique in the MBTA. For one thing, the restored cars that run on the 2.6-mile spur are from the 1940s, giving the line the vibe of a rolling railroad museum. It is also not a straight shot to downtown Boston; passengers who board the train at Mattapan or the four closely clustered stops in Milton must get off the trolley at Ashmont and get on a regular Red Line train. Eliminating the trolley is not a brand new idea: The MBTA itself in the past floated the idea of replacing the trolley with buses.

Before the pandemic, the trolley recorded about 6,600 daily boardings; the line now serves around 3,700 riders a day, according to the T.

A theory popular with some residents is that the trolley is something less than the other MBTA lines and therefore not “rapid transit.” If that is the case, Milton would fall into a less intensive category under the guidelines for the MBTA communities law, that of “adjacent community.” The Planning Board made this argument in a Sept.15 letter to Thomas Glynn, chair of the MBTA board of directors.

The letter begins: “The Milton Planning Board writes to respectfully request that the MBTA remove the Mattapan Trolley line from its classification as rapid transit. We believe the past history, present usage, and projected future plans of the line confirm that the Mattapan Trolley is not rapid transit.”

If state officials buy this argument, it would reduce Milton’s obligation to zone for new housing, from 2,461 theoretical units to about 984, as well as extend the town’s deadline by one year.

Throughout the long debate this summer, Czerwienski has publicly maintained that complying with the law would be good for the town.

For one thing, it is, you know – the law. Also, a variety of apartment and condominium options would serve people priced out of Milton as well as current residents trapped in big homes they no longer want. As Czerwienski put it, “The people who want to live in these multifamily spaces are already here.”

He also believes that encouraging denser housing around transit is the best thing a town can do to get cars off the road and combat climate change. Great benefits, in his view, though as he repeatedly acknowledged, it’s not his call.

Town Meeting decides what Milton will become, as it always has. The vote, which may resonate far beyond the town’s borders, is expected in December.

Mark Arsenault can be reached at [email protected]. Feedback and tips can also be sent to the Boston Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected], or by calling 617-929-7483. Mail can be sent to Spotlight Team, the Boston Globe, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

Beyond the gilded gate

People in and around Boston are being challenged, in ways never before, to address the region's unprecedented housing crisis. The Globe Spotlight Team probed this question and found yet another crisis: One of consensus and will.

Preview: Data

Graphics: Why it’s so hard to afford housing in Boston

Part 1: Milton

In towns like Milton, home prices are a threat to prosperity. But they don’t have to be

Map

How will the state’s historic rezoning mandate affect your community?

Part 2: Generations

One house, one family, and the fading dream of homeownership

Part 3: Luxury towers

Reckoning with Boston’s towers of wealth

Part 4: Brookline

An identity crisis comes to Brookline

Part 5: Single-family zoning

Reimagining an American ideal

Part 6: The renters

A Boston building, scattered souls, and rent control revisited

Part 7: Construction costs

The $600,000 problem. Why does it cost so much to build housing in Boston, and what can we do about it?

Calculator: Construction costs

Calculator: Penciling out a project

Credits

- Reporters: Mark Arsenault, Andrew Brinker, Catherine Carlock, Stephanie Ebbert, Diti Kohli and Rebecca Ostriker

- Editors: Patricia Wen, Tim Logan, Mark Morrow

- Photographers: Lane Turner, Jessica Rinaldi, Erin Clark, Craig F. Walker, Pat Greenhouse, David L. Ryan, Jonathan Wiggs

- Photo editors: Leanne Burden Seidel and Bill Greene

- Video producers: Olivia Yarvis, Randy Vazquez, and Dominic Smith

- Video director: Anush Elbakyan

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development, graphics, and data analysis: Daigo Fujiwara

- Development: John Hancock, Andrew Nguyen

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanac and Jenna Reyes

- SEO: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2024 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC