Second of a two-part series

They were brave, they were frightened, they were desperate.

The five respected physicians had seen and heard enough, and they were now bound and determined to stop Dr. Yvon Baribeau, a heart surgeon whom they saw as having a long history of deadly errors in the operating room. Three of them had already gone up the chain of command at Catholic Medical Center, with urgent appeals, but had been largely rebuffed by hospital leadership. The other two feared the hospital had lost its moral compass and allied themselves with the effort.

A celebrated surgeon,

a trail of secrets and death

Part one

Colleagues tried to stop a surgeon who would set a record for malpractice settlements. Hospital executives let him go on and on.

Part two

A crisis of conscience, with lives on the line

Chronology: What the public didn’t know about Dr. Yvon Baribeau

Secrecy pervades medical malpractice settlements

And so the five resolved to join in an almost unimaginable step: to go straight to the organization that founded and still oversees the hospital.

They were taking their case to the Church.

One by one, in early 2018, the five visited a priest at a church just a few miles from Catholic Medical Center in Manchester, N.H. Monsignor John Quinn, a former diocese appointee to the hospital board of trustees, had agreed to see them in the strictest confidence, something like the seal of the confessional.

The physicians wanted it that way because they had an extraordinary request: Please help us stop Dr. Baribeau.

They knew they might be risking their careers by seeking to oust one of the top revenue-generating surgeons at the hospital, but they believed Baribeau was making more and more deadly mistakes. After decades in Manchester, a Boston Globe Spotlight Team investigation has found, he would become the US physician who accumulated the highest number of malpractice settlements involving surgical deaths in the last two decades, a database shows. In the previous year alone, six Baribeau patients who had died or were allegedly injured by his surgeries would become the subject of malpractice claims and settlements. And he was still operating.

One of those patients, a retired Army officer, lost so much blood after Baribeau allegedly lacerated a major blood vessel during heart surgery that clinicians had to replenish her entire blood supply nearly five times, according to a hospital colleague who reviewed the transfusion records. It wasn’t enough; she died the next day.

There were many cases as disturbing as this. And though the five doctors couldn’t know it at the time, the pattern would only worsen; the season that came to be known at CMC as the “summer of death” lay just ahead.

For the doctors, all this was more than a medical travesty, it was a crisis of conscience. They felt haunted by the likelihood that the patient harm would continue and brought those facts and feelings to Monsignor Quinn.

Dr. Paul Del Giudice, who led CMC’s anesthesia department for many years, recalled unburdening himself to Quinn as they sat in armchairs a few feet from each other in the priest’s modestly appointed office. Del Giudice confided that many doctors were deeply troubled about Baribeau but felt powerless in the face of an administration that had sought to silence or oust some who complained.

He recalls that Quinn nodded and listened during the meeting — but made no promises.

Maybe, the doctors hoped, Quinn could prevail upon Bishop Peter Libasci of Manchester to intervene.

“We truly thought we could effectuate at least some sort of change,” said Del Giudice, who had witnessed Baribeau’s work in the operating room for more than two decades.

Another doctor who had sat down with Quinn — and who asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals from CMC leaders — said he and the others had “this horrendous moral dilemma going on” and being able to share this with the priest was deeply meaningful.

“Then I could be at peace, having done as much as I could,” he said.

It remains unclear if Quinn, or anyone in the diocese, acted on the pleas. Quinn has maintained public silence about these visits to St. Elizabeth Seton parish in Bedford, N.H. When a Globe reporter went to his rectory in May, he declined to confirm that the visits had happened at all.

“If any people came to speak with me, that would have been under the confessional seal or counseling, and it would be confidential,” he said.

The bishop’s office also declined to comment when asked about these visits.

These doctors were acting out of humanity, the value at the core of the medical profession, but were also part of something rarely seen in the annals of American medicine: a protracted uprising led by medical professionals against a prominent colleague and hospital leadership.

They were joined in this by a growing number of staff in the 330-bed Catholic Medical Center who were alarmed by the administration’s recent approach in dealing with Baribeau. In previous years, administrators had disciplined Baribeau after investigating allegations that he had endangered patient safety — including once imposing a 28-day suspension of his operating privileges.

But as tragic outcomes were happening more frequently, hospital leaders appeared to be shielding Baribeau from consequences, according to numerous current and former medical staff who spoke to the Globe. Some doctors who voiced serious concerns about Baribeau faced administrative actions that many colleagues saw as retaliation.

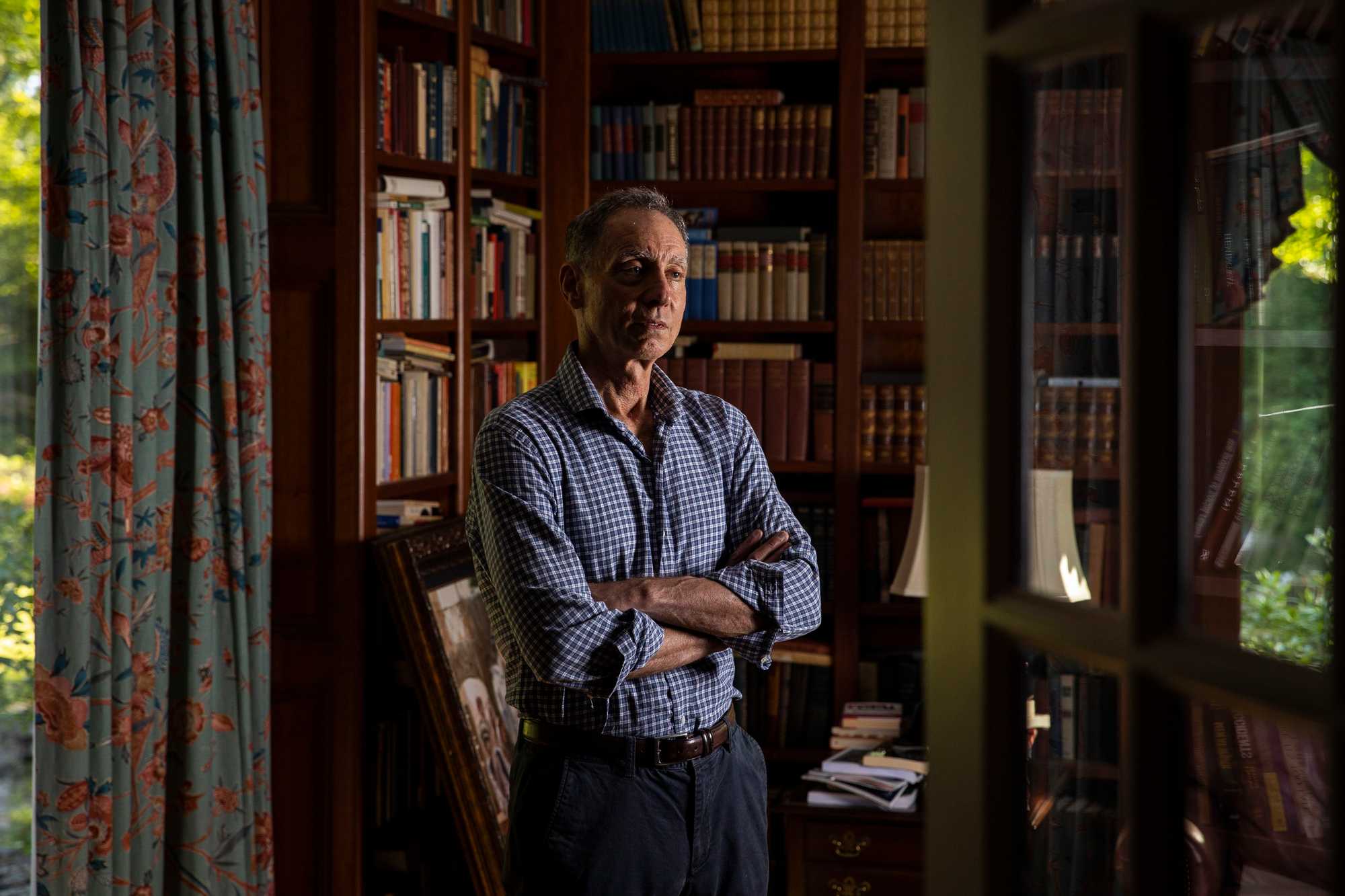

![The hospital administration “should have booted [Dr. Yvon Baribeau] off the medical staff years ago,” said Dr. David Fontaine, a former head of radiology at Catholic Medical Center, who served on a key hospital committee charged with upholding physician standards.](/2022/09/07/metro/investigations/spotlight/trail-of-secrets-and-death/static/06439a418c8349b85b2bc57b09f3d0f8/08d39/F57FBHOKVW2OYFB3SSXAKJKNAA.jpg)

Dr. David Fontaine, a radiologist who served on a key CMC committee charged with upholding physician standards, said the administration “should have booted him off the medical staff years ago,” but he brought in coveted revenue for the hospital.

“It’s the pursuit of money over the quality of patient care,” said Fontaine, who still practices at the hospital.

Top hospital officials adamantly deny they ever put profits ahead of patient safety, or retaliated against any clinician for speaking out against Baribeau. But many longtime doctors say some personnel moves, such as the abrupt ousting of cardiologist Dr. David Goldberg, sent an unmistakable message. One day in 2016, Goldberg, a prominent Baribeau critic, was suddenly placed on leave.

Goldberg would later file a federal whistle-blower lawsuit, which included disturbing allegations that Baribeau had caused needless deaths over half a dozen years. Some nurses, distressed by Baribeau’s surgical errors, would take action as well, including collecting a list of troubling cases to present to administrators.

And the sense of alarm would soon reach local lawyers, who wrote forceful letters in 2018 to the state Board of Medicine and the hospital, demanding that Baribeau stop practicing and warning CMC of its legal risk if he did not. About two years later, Baribeau would settle 17 malpractice claims. bringing to 21 the total number of settlements he agreed to over his career.

Baribeau, now retired, has declined multiple requests for an interview with the Globe, but his attorney, Beth Catenza, said Baribeau made patient safety his top priority. In an e-mail, she said Baribeau is the victim of “a group of physicians with a long history of personal bias against him,” but declined to give specifics.

She defended Baribeau as a conscientious professional who worked hard to build CMC’s heart program and “prided himself on giving even the sickest of patients a chance at survival, when other surgeons would not.”

And she said Baribeau’s treatment of patients was repeatedly supported by experts across the country, including independent reviewers who found his care of patients in 2018 was “reasonable, appropriate, and within the standard of care.”

In a separate e-mailed statement, Baribeau said he was informed of 17 malpractice claims against him in 2020, after his retirement, and he ultimately agreed to settle them with no admission of wrongdoing. Baribeau also said the Globe’s questions about his care of patients contained “significant errors” but both he and Catenza declined to identify any specific inaccuracies, citing patient privacy laws.

“I am proud of the care I provided to patients throughout my career at Catholic Medical Center,” Baribeau said.

But more than two dozen current and former medical staff at the hospital told the Globe this was a grim period in the hospital’s history, and many said that they want not just Baribeau but the administrators who oversaw him — some still in power — to be held accountable.

The moral stakes are clear, said Dr. Weldon Sanford, the current chief of pathology at the hospital, and require action.

“I’m a person of faith and I’ve got to face my maker someday. And if I don’t do what’s right, I can’t live with myself,” Sanford said.

The protection of Dr. Baribeau

Dr. Raef Fahmy was one of the first to face sanctions after speaking up.

Drs. Raef Fahmy, David Goldberg, and Patrick Mahon

Current and former doctors at CMC

He held the prestigious position of chief medical officer at CMC, appointed by the CEO to oversee the medical staff. This skilled foot and ankle surgeon, however, participated in a contentious meeting in late 2014 about Baribeau with top doctors and administrators and recommended that a neutral third party be brought in to help bring the crisis to an end.

Afterward, as Fahmy recounted in an interview, a top administrator called him into his office.

“Here’s how the conversation went: ‘We’re kind of concerned about your attitude around here. It seems you’re angry and upset all the time. You can’t be CMO, you’re not objective,” Fahmy said.

Fahmy was demoted from his post, then removed from hospital committees and isolated in a tiny office.

This would be followed up a couple of months later with a letter from the hospital CEO, according to a confidential legal document obtained by the Globe, admonishing him for speaking directly to some hospital trustees “to voice a concern that not enough was being done” about Baribeau, and “not going through the appropriate chain of command.”

Fahmy chose to leave CMC voluntarily in June 2015 and took another job in the Midwest.

He was among three high-profile physician leaders who were on the receiving end of personnel actions that many of their colleagues saw as retaliation for expressing serious concerns about Baribeau. At times, the offending actions had involved telling people outside the administration about the problems with Baribeau, violating what appeared to be an unwritten protocol of the hospital.

Hospital officials have declined to comment about any of these personnel actions but deny they had anything to do with Baribeau.

“For anybody to suggest that they were let go from CMC for raising concerns is absolutely false,” said CEO Alex Walker, who joined the hospital as general counsel in 2012.

Dr. Joseph Pepe, who preceded Walker as CEO before stepping down last year, also said any “separations” initiated by management would have been due to behavioral issues, or “breaking policies after multiple warnings.”

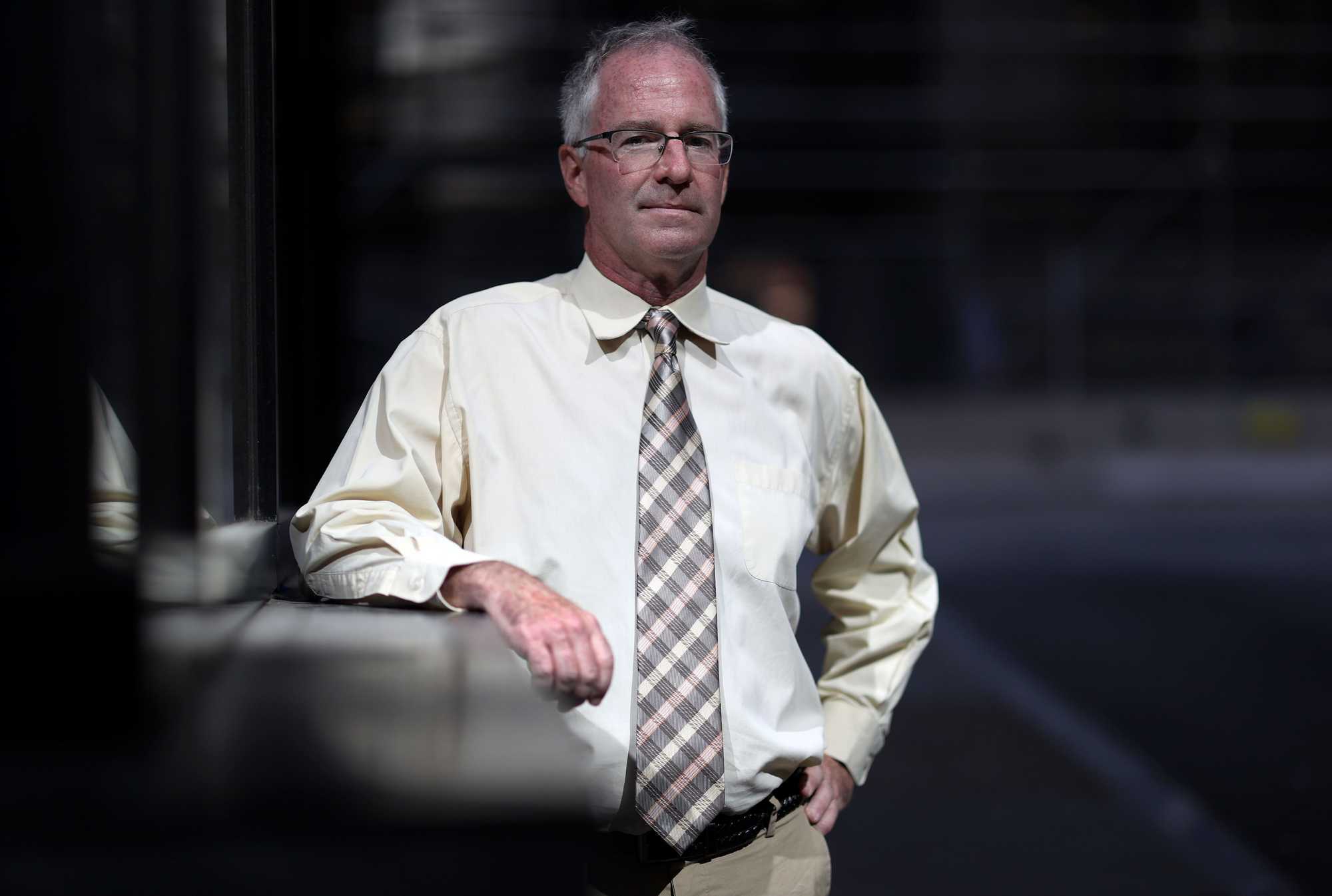

But then there is the experience of Dr. Patrick Mahon, a longtime vascular surgeon who still works at Catholic Medical Center.

Mahon, the former chair of surgery and president of the medical staff, led the hospital’s peer-review committee in late 2017, when the committee was alerted that Baribeau had allegedly repeatedly mishandled an artificial heart valve, botching its implantation three times during a surgery performed on one patient.

So in January 2018, Mahon contacted a company representative to learn more about the valve, which has a special method of insertion.

Word that he had done so reached administration officials, who were so upset they temporarily held up Mahon’s hospital employment contract, accused him of creating a “hostile work environment” for Baribeau, and threatened him with termination if there were future missteps, according to a letter from an administration official obtained by the Globe.

“That is pure intimidation and retaliation by the hospital,” said Mahon.

And the doctor said he believed he knew the reason for it. He recalled that Dr. Louis Fink, executive medical director of Catholic Medical Center’s flagship heart institute, once likened Baribeau to UCLA’s Lew Alcindor, the future pro basketball star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who was so important to his college team that his coach believed he deserved special leniency for infractions.

Dr. Goldberg, the cardiologist and Baribeau critic, had moved up the ranks at CMC and was about to rise to the role of president of the medical staff. He had been vice president of the medical staff, a prestigious position to which he was elected by hospital doctors. The president’s post would have given him a seat on the board of trustees.

But executives abruptly placed him on administrative leave without warning one day in November 2016.

The confidential legal document obtained by the Globe suggested the administration’s reason for his removal related to workplace outbursts and other un-collegial behaviors.

Goldberg was widely respected among physician leaders at CMC for his passionate commitment to patients, top surgical skills, and strong ethical compass. But he could also be a divisive figure, known for his exacting style and outspokenness that some found abrasive and disruptive.

Alyson Pitman Giles, the hospital’s CEO before Pepe, remembered Goldberg as “a pain-in-the-ass guy,” she said. “But he was the best cardiologist there.”

Goldberg soon negotiated departure terms with the hospital. But being pushed out of an institution he cared deeply about was personally devastating for him and sent a chilling message to the doctors as a group.

“With the unilateral dismissal of David Goldberg, a culture of fear has been created within the medical staff at large,” wrote Dr. Jonathan Vacik, a former emergency department director, in a January 2017 e-mail to fellow doctors that was obtained by the Globe.

The decision to remove Goldberg would not only create a stir in the hospital, it would set the stage, in the years to come, for him to file a whistle-blower lawsuit that would later become public, exposing the very controversy the hospital leadership wanted so badly to keep under wraps.

Meanwhile, as CMC leaders moved against Baribeau’s critics, they also instituted new policies that had the effect of increasing protection for the surgeon himself.

Around 2015, CMC introduced a revised quality-assurance system that reduced the power of physician leaders to determine which cases warranted review and potential discipline and gave more power to the new chief medical officer, Dr. William Goodman, according to multiple current and former doctors.

Goodman led a team made up mostly of nurses that vetted cases and could intervene to challenge the ratings of medical leaders, according to colleagues and hospital documents.

The result, doctors said, was that Baribeau’s troubling cases no longer underwent the same kind of rigorous peer-review process in which fellow doctors determined what went wrong and devised potential remedies, including whether disciplinary action was recommended.

Multiple doctors said Goodman intervened in the process in ways they believed protected Baribeau.

Del Giudice, the anesthesiologist, said he repeatedly alerted a top quality-assurance nurse about troubling Baribeau cases, for potential investigation. “She’d pull the chart,” Del Giudice recalled. “She would go to Goodman, and he would say no,” because the case had already been discussed in a less formal setting.

Goodman told the Globe he would never block the examination of a case that way, and it was “not compatible with my way of handling patient care and safety.”

He also defended the quality-assurance changes as an improvement that was based on “best practices from other hospitals in the state” and brought more voices to the process.

But others saw the new review system as a way executives could reduce the risk of Baribeau getting any additional discipline. That was important, as the surgeon’s standing was on the edge. A letter from the board chair in 2015 noted he had had three major problematic cases and a fourth might bring termination.

“Requirements basically slid away, and [Baribeau] was left to do whatever he wanted to do whenever he wanted to do it,” said Fontaine, a former head of radiology at CMC who served on the committee overseeing physician standards.

Dr. Diane Biron, a former chair of medicine who also served on the committee, said the changes gave Goodman too much power and meant physician leaders were not in the loop about some troubling cases. As time went on, she said, “it was becoming very clear we were not being kept aware of issues that were happening” with Baribeau.

Questions around death data

It was August 2018, and one unconscious patient in the ICU had captured the attention of doctors and nurses. The elderly man had undergone double bypass surgery performed by Baribeau. Soon afterward, his vital signs crashed, and now he was tethered to a whooshing heart-lung machine.

As the tissue in his chest began to blacken and die due to lack of blood flow, horrified staff were certain he would not survive. Yet, they said, Baribeau kept him on the machine and led the patient’s family to believe he might recover.

“He was rotted from the inside out,” said Dr. William Kelley, an anesthesiologist at the hospital. “The chest wall was gone. It was black and necrotic. But the family was told otherwise.”

Some clinicians suspected they knew why Baribeau encouraged this course: When it comes to cardiac surgery quality measures tracked by the federal Medicare program and other groups, a patient who dies within 30 days is typically counted as a potential surgery-related death. One surgical quality organization, however, also did count hospital deaths after 30 days as possibly connected to the surgery – but not if that patient died after being transferred to a hospice program.

“The patient was kept alive for 30 days,” wrote another physician in a Google document he created later that month to record Baribeau’s troubling cases and shared with the Globe. “On day 31 he was placed on palliative care. It was well known to ICU staff that this patient was rotting for at least the last 2 weeks of his life but was kept alive to avoid a death within 30 days.”

Staff interviewed by the Globe said some CMC cardiac surgeons pushed the 30-day goal, especially Baribeau. They say these lengthy periods on ventilators — when the patient has little or no prospect for survival — gave false hope to the families and wasted resources and could cause unnecessary suffering for patients.

“He would say, ‘We are pushing forward with this patient....You’ve got to keep doing it for 30 days,’” said one former CMC physician who did not want to be identified for fear of career repercussions. “Those things didn’t make sense. All of these patients would die regardless.”

Baribeau’s lawyer, Catenza, and hospital officials vehemently deny that patients were kept alive in part to manipulate mortality data, an assertion also made in Goldberg’s whistle-blower complaint. “Dr. Baribeau categorically denies that he ever tried to manipulate surgical mortality data,” she said in a written statement.

Walker, the CEO, said the hospital investigated the allegations and found them to be “just utterly false.”

Retired ICU nurse practitioner Mary Sanford, who worked with Baribeau for 16 years, said the surgeon did keep patients longer on life support than some colleagues, but felt she understood his reasons.

“Dr. Baribeau was not a person who liked to give up,” said Sanford. He wanted to give them every opportunity for survival, she said, and there always was the outside chance of “miracles.”

Dr. Louis Fink, executive medical director of Catholic Medical Center's flagship heart institute (left), and Alex Walker, CEO of the hospital. (Catholic Medical Center)

But eight current and former physicians, nurses, and other staff told the Globe they believed Baribeau had less honorable motives for prolonging some patients on life support. And some reported their suspicions to administrators.

Pepe, who was CEO at the time, denied that CMC allowed any such behavior by Baribeau, but he acknowledged that staff had raised concerns. “It was brought to my attention that sometimes [Baribeau’s patients] were in the ICU a long period of time, and that caused a lot of people to be upset,” he told the Globe, but did not elaborate.

In a letter to the Globe in June, Fink, medical director of the hospital’s heart institute, called the accusations of manipulated data in the hospital “outrageous.”

Hospital data, he also said, found that of about 1,700 patients operated on by CMC’s cardiothoracic surgeons from early 2017 through 2018, just two died in a hospital bed after 30 days, and three others died in a hospital-based hospice program after 30 days. The total number is so low it “does not support a widespread conspiracy,” and any impact on mortality data “would be negligible,” Fink wrote.

But others are not so sure. A tactic designed to manipulate mortality data is what John Coll believes was behind his 52-year-old sister’s sudden transfer from the ICU into hospice after 30 days.

Maggie Coll

Cardiac surgery patient

In early 2017, Coll got news that his sister, Maggie, was on the brink of death: The former teacher’s valve replacement and coronary artery bypass surgery done by Baribeau more than 30 days earlier had failed to fix her heart troubles, she had been maintained on a ventilator after surgery, and now she was crashing. Even the ventilator wasn’t going to keep her from dying. Coll also heard from relatives that he needed to get to the hospital right away; he had power of attorney for his sister, and he needed to sign paperwork to transfer her into hospice before she died.

Another sister, a retired disability lawyer who had been at Maggie’s side during much of the hospitalization, explained the reason for this urgent request as she understood it: It was all so Maggie’s death wouldn’t hurt the hospital’s surgical survival rates. He later heard a similar reason given by a malpractice attorney who contacted him about his sister’s case.

They were “playing with the numbers,’' Coll said, even as his sister’s life ebbed away.

Baribeau becomes a patient

On a late April day in 2018, something was clearly wrong with Baribeau. He was pale and sweaty and seemed to be working in pain, according to a colleague who saw him in the operating room. He canceled a scheduled surgery and went to the ER.

Suddenly the doctor was the patient. Word spread quickly in the hospital that he had been diagnosed with colon cancer, requiring an emergency operation that day.

There was no formal announcement by administrators to explain Baribeau’s absence. Colleagues knew someone in his condition would typically start chemotherapy, after taking six weeks or so to heal from surgery. Then the treatments themselves would take months. The expectation among colleagues was that Baribeau would not be in the OR for a stretch because of the sometimes debilitating side effects of the therapy.

But about a month after surgery, Baribeau quietly requested a medical clearance letter from Dr. Robert Catania, the general surgeon who had done his emergency operation, to return to work in the operating room.

The letter, obtained by the Globe, states, “Yvon Baribeau is able to return to work starting on May 21st. At this time, there are no restrictions on his activity.”

Reached by the Globe, Catania said he could not discuss Baribeau’s health because of confidentiality requirements. He confirmed that he had signed the clearance letter but expected it would just be a temporary measure.

Baribeau started chemotherapy May 31, and got treatments every other week, according to the confidential legal document obtained by the Globe.

Catania, a former president of the medical staff, said he also repeatedly urged Baribeau to alert the medical staff services office of his condition and treatment, as required by hospital policy to ensure no staffer is too impaired to safely do their job.

Baribeau responded that the chief medical officer, Goodman, was “aware of his situation,” Catania said.

A serious illness of a colleague often generates sympathy in the workplace. But in this case, staff reactions were complicated. Some already doubted Baribeau’s surgical competence. When Baribeau was restored to the operating room schedule in June, many worried he might be operating while impaired by his illness and chemotherapy treatment.

Few knew much about Baribeau’s overall health, or his personal life. He was now 62, and had spent nearly all of his career — and long grueling hours — at Catholic Medical Center. Still he was largely an enigma.

His halting gait in the past betrayed serious back troubles. Over the years, he underwent several back surgeries and procedures on both of his hands for Dupuytren’s contracture, a condition that Baribeau said ultimately impaired his ability to use “fine instrumentation safely,” according to documents that he filed after retirement in a 2020 disability insurance lawsuit.

Mary Beth Jenkins, who oversaw the operating room as the hospital’s executive director for surgical services, was among numerous staff who became deeply concerned that he might be too impaired to operate. “I went to Bill Goodman myself and said, “Why is he doing surgery? I want to know who cleared him,” Jenkins said.

She said Goodman, the chief medical officer, stammered out a response, suggesting clearance was forthcoming.

Goodman said he couldn’t comment on any staff member’s health or personnel issues and said he acted properly and fairly implemented policies during this time.

Baribeau’s attorney told the Globe that he “never operated while impaired,” and that “CMC was fully supportive” of his decision to return to the operating room. Hospital executives refused to discuss the matter, saying it was confidential personnel information.

But one thing was known as May of 2018 gave way to June: Baribeau was coming back to the OR. Tragedy would follow close behind.

A whistle-blower claim and the ‘summer of death’

While Baribeau prepared to return to surgery, Goldberg continued to move forward with his own plan. More than a year had passed since he had been forced out of the hospital, and it had been a stressful time for him and his family. Goldberg had moved on to work elsewhere, but he remained alarmed about Baribeau still operating on patients unaware of his history of errors.

The cardiologist was working on a federal whistle-blower lawsuit with a prominent figure in New Hampshire legal and political circles: Charles “Chuck” Douglas III, a former congressman and judge.

In June 2018, they filed under seal against CMC that largely focused on Baribeau but also detailed an alleged Medicare kickback scheme involving a medical device company and another local cardiologist who referred many cases to the hospital.

The rest of the document focused on allegations that about a dozen Baribeau patients died or were harmed by his “substandard care,” and that he tried to manipulate his mortality statistics with some patients. The suit identified patients by initials only. The Globe was able to identify the patients through interviews and records.

The hospital “has created a practice of covering up medical errors so that they do not reach the patients or their families,” the whistle-blower suit read.

Goldberg would later suffer a setback at a new job at Holy Family Hospital in Methuen, one that was reminiscent of the reasons CMC had given for forcing him out — that he could be abrasive. Though he felt that he was flourishing overall and had taken on leadership positions, Goldberg was cited last year by administrators at Holy Family for noncollegial behavior in the cardiac catheterization lab.

After discussions with supervisors, he came to the humbling realization that he needed to better cope with all the stress in his life and improve his communication style. He said he voluntarily agreed to temporarily surrender privileges to work in that unit and to undergo some counseling.

Meanwhile, Goldberg would face an uphill battle in persuading federal prosecutors to pursue his allegations against Baribeau. Malpractice cases typically involve state negligence laws and are handled in state civil courts. Veteran lawyers say federal prosecutors are typically reluctant to litigate what are essentially medical malpractice claims in a whistle-blower lawsuit.

“Historically, the government has tended to shy away from second-guessing medical decision-making,” said David Lazarus, a former federal prosecutor in Boston. “It becomes a battle of the experts.”

But the suit would eventually put CMC executives on notice that word of Baribeau’s problems was leaking out beyond the hospital walls.

Inside Catholic Medical Center, Baribeau, who had begun treatment for cancer, donned scrubs and returned to the OR in June 2018.

What followed was a harrowing two months for the cardiac surgery staff – a period that numerous current and former Catholic Medical Center doctors still refer to as “the summer of death.”

In a single five-week stretch, three of Baribeau’s patients died and two were severely injured in surgeries that were later part of medical malpractice settlements.

Interviews, hospital records, and other documents obtained by the Globe provided some information about the patients, all men over 60, who died or were injured during this period:

One elective heart-surgery case that July included a problem with the same kind of heart valve that Baribeau had previously experienced trouble implanting; substantial post-op bleeding followed. The patient was cognitively impaired and later died.

Later that month, Baribeau sawed through a man’s sternum near the edge instead of the midline. According to a CMC document obtained by the Globe, this probably made it harder for the sternum to be wired shut properly, and the man’s chest opened up after surgery. Because of complications, one leg was amputated, and the patient spent months in the ICU before being released.

That summer, it seemed clear Baribeau was struggling physically, though still there was much secrecy around his condition. Baribeau “was sick, he was coughing a lot,” recalled Margaret Rodriguez, a former CMC operating room director. “At one point I was in his OR, I must have fed him seven cough drops behind his mask.”

Margaret Rodriguez

Former operating room director at CMC

Finally nurses, anguished about Baribeau’s risk to patients, stepped forward, bringing the problem directly to the administration.

One of the cardiac nurses came to Rodriguez’s office. The nurse “sat down, and she said, ‘I just don’t want to see another innocent patient die unnecessarily,’” recalled Rodriguez. “I said, ‘I understand, and I will bring this forward.’”

Rodriguez met with a high-ranking administrator who wanted specifics, so Rodriguez enlisted help from Terry Beauvais, a longtime nurse first assistant who had been at Baribeau’s side during numerous troubling cases. Together, they got approval to pull patient records for several cases, Rodriguez said, and Beauvais wrote a memo detailing what happened in those cases.

When Rodriguez met again with that administrator, “I remember her saying ‘What outcome do you guys want?’” Rodriguez recalled. “I said, ‘I would love it if he never came back into the OR again.”

The administrator was silent, betraying nothing of what she would do next.

By late summer, concerns about Baribeau’s health and performance had reached other administrators, and Baribeau’s name disappeared from the surgical schedule. There was no official explanation from the administration about why.

It seemed that, perhaps, the surgeon was going to quietly fade from the scene.

That sense of relief on the CMC staff was, however, temporary. By the end of 2018, Baribeau’s name would appear back on the schedule, and he would be on call to see patients on Christmas Eve.

This time, however, some powerful lawyers were engaged.

On Dec. 6, Douglas, the lawyer for Goldberg in the whistle-blower case, sent to the New Hampshire Board of Medicine, imploring the board to quickly suspend Baribeau’s license, writing that the surgeon’s “continued access to patients poses a risk to public safety.”

Baribeau, he wrote, “has committed a series of unreported, avoidable instances of medical malpractice and neglect, resulting in loss of limb and life to his patients.” He said hospital administrators “have failed to take necessary steps to protect their patients in the face of Dr. Baribeau’s physical and mental decline.”

A week later, hospital executives got an ominous letter from one of the top malpractice firms in New Hampshire, Abramson, Brown & Dugan. One of the firm’s attorneys, Holly Haines, addressed Catholic Medical Center’s director of risk management, attaching a copy of Douglas’s letter to the medical board and alerting the hospital that her office represented numerous families in malpractice investigations involving Baribeau.

“We understand that Dr. Baribeau has been put back on the surgical schedule this month, and wanted to make sure CMC was aware of their risk exposure if any additional patients are harmed,” she wrote in the letter reviewed by the Globe.

Baribeau’s name would be removed from the Christmas Eve schedule — and would remain off it for good.

Hospital executives later told the Globe that in 2018-19, the New Hampshire medical board investigated at least a dozen of Baribeau’s cases, with access to patient records, and did not take disciplinary action against him. The board would not comment.

The following year, Baribeau was briefly assigned to a CMC outpatient center to perform vascular surgery, but that didn’t last long. In August 2019, then-CEO Pepe Baribeau’s retirement.

“I know I speak [for all of us] in being grateful for Dr. Baribeau’s vision and commitment to his colleagues, his patients, and to advancing cardiac care in New Hampshire,” he wrote. “His presence will undoubtedly be missed here, but please join me in thanking him for his dedication to CMC and wishing him the very best as he begins a new chapter in his life.”

Questions about the future

To this day, top hospital executives continue to reiterate their support of Baribeau — and none of those who oversaw Baribeau has faced any known review or consequences for the 21 medical malpractice settlements now linked to him.

The waiting room for cardiac surgery patients at CMC still features a group photo with a smiling Baribeau — part of the advertisement that once ran in multiple newspapers.

There appears to be no pressure from the New Hampshire Board of Medicine to account for what happened. Its website continues to show a flawless record for Baribeau. The board, however, does have a new member: Goldberg, the former CMC cardiologist who filed the whistle-blower suit, was appointed earlier this year by the governor.

“My priority as a doctor has always been to advocate for top medical care and patient safety,” Goldberg said.

Baribeau, now 66, apparently still lives in a suburb outside Manchester. A woman describing herself as his wife answered the door this spring but told reporters Baribeau was not home and asked reporters to leave. When the Globe asked Baribeau’s attorney if the doctor intends to return to surgery, she said Baribeau “is retired and has no intention of returning to practice.”

Since leaving CMC, he has also filed a lawsuit against his long-term disability insurer, contesting its decision on benefits and revealing a history of back and hand troubles that he said prevent him from working.

Newsletter: The Globe Investigates

Sign up to recieve Spotlight reports and special projects in your inbox

The whistle-blower suit concluded earlier this year, with federal authorities exacting $3.8 million from CMC to settle claims involving the cardiology kickback scheme, but the allegations of malpractice and manipulated mortality were dropped.

Douglas, the attorney representing Goldberg in the whistle-blower suit, said he and Goldberg were disappointed authorities did not act on the Baribeau-related cases, though they believe the lawsuit — unsealed in February this year — drew public attention to the painful secrets inside CMC and the hospital’s complicity. Meanwhile hospital officials hailed the mixed outcome as an exoneration.

Federal authorities declined to comment about the allegations against Baribeau but noted they reserved the right to re-open the matter involving the surgeon later, though that rarely happens.

As is standard in such cases, the whistle-blower, Goldberg, received a percentage of the settlement; in this case, he got 15 percent, which came to about $570,000, plus expenses.

When asked in an interview with Globe reporters this year if they would hire back Baribeau, should he renew his surgical license, CEO Walker did not answer immediately. There was a long pause.

“Yes, I mean, subject to … the processes that we follow to grant privileges in the hospital, subject to, you know, his skills being up to date,” he said. “Absolutely.”

Send comments and tips to [email protected], or at 617-929-7483. Or write to the reporters on this story at [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; and [email protected].

Credits

- Reporters: Rebecca Ostriker, Liz Kowalczyk, Jonathan Saltzman, and Deirdre Fernandes

- Spotlight Editor: Patricia Wen

- Other editors: Scott Allen and Mark Morrow

- Multimedia editor: Christina Prignano

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara

- Photographers: Erin Clark and Jessica Rinaldi

- Photo editors: William Greene and Leanne Burden Seidel

- Animation: Dominic Smith

- Video editor: Anush Elbakyan

- Copy editors: Michael Bailey and Mary Creane

- Audience engagement: Maddie Mortell and Devin Smith

- Newsletters: LaDonna LaGuerre

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Data analysis: Yuriko Schumacher

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2022 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC