The desperate and the dead: prisons

There may be no worse place for mentally ill people to receive treatment than prison

yet a growing number end up in the ‘new asylums’

Nick Lynch hesitated at the prison door, pausing on the threshold as he stood between two worlds. Muscled and tattooed, 26 years old, he blinked at the brightness of the sun, the springtime colors.

One more step, then freedom, for the first time in eight years. He had dreamed about this moment; he had feared it, too.

Ahead of him on that April morning in 2012 lay the most treacherous passage an inmate can face: the transition back to normal life. More than 40 percent of prisoners who attempt it fail, ending up back in jail or prison. For those who carry mental illness with them, like Nick Lynch, failure looms larger and occurs even more often.

In the parking lot at Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center, a maximum-security prison 40 miles northwest of Boston, Nick’s father turned to him and raised a camera. Before him stood the son he’d lost eight years ago, with the prison walls looming fortresslike behind him. Someday years from now, his dad thought, Nick would look back at this day and see how far he’d come.

His father had spent months preparing for his son’s release. A Navy veteran who worked in health care, Kevin Lynch had bought a fixer-upper on Cape Cod to renovate with his son, a project that would help the two of them get reacquainted. He planned to help Nick enroll in college while taking graduate courses himself; they would navigate this new world together.

But Nick was sicker now than when he’d gone to prison.

For most of his imprisonment, according to Nick, he received little treatment for his mental health and limited access to medicine that helped him. Long stretches in segregation made his illness worse. In an account confirmed by his medical records, he says his condition spiraled downward near the end of his sentence, when he attempted suicide and mutilated himself, biting a piece of flesh the size of a quarter from his own wrist. His desperate acts finally led to better care, including medicines that eased his symptoms, he says.

Like many inmates, Nick used illegal drugs while he was locked up, but says he received no treatment for addiction. Nor was he referred for any when he was released, say Nick and his dad, even though his discharge papers, signed the day of his release, list substance abuse as a “chronic medical problem.”

A spokesman for the Department of Correction declined to discuss Nick’s treatment in detail, but said prison clinicians appeared to follow protocol, increasing care as Nick’s condition worsened. The spokesman defended the prison’s release planning, too, saying staff helped arrange for Nick’s continuing treatment.

But when it came to his son’s mental health, Nick’s father says, he was the one pushing for a plan — and doing the legwork to find willing providers.

What Nick carried with him, walking out of prison, seemed like so much less than what he needed: a few plastic packets of pills, bundled together with rubber bands; an appointment at a treatment center that his dad says he had contacted.

They would celebrate his homecoming together at a gray-shingled tavern on Cape Cod, his family filled with hope and visions of his future. Overwhelmed by the menu and the server’s questions, Nick lowered his eyes and let his sister order for him.

He had been a teenager when he was locked up. Now, he was a man starting over again. He did not know then how briefly his new life would last: 103 days, precious and desperate, leading back to trouble, punishment, and regret.

Last year, more than 15,000 prisoners walked out of Massachusetts jails and prisons. More than one-third suffer from mental illness; more than half have a history of addiction. Thousands are coping with both kinds of disorders, their risk of problems amplified as they reenter society.

Within three years of being released, 37 percent of inmates who leave state prisons with mental illnesses are locked up again, compared with 30 percent of those who do not have mental health problems, according to a Department of Correction analysis of 2012 releases. Inmates battling addiction fare worse: About half are convicted of a new crime within three years, according to one state study. And inmates with a “dual diagnosis” of addiction and mental illness, like Nick Lynch, do the worst of all, national studies show.

Despite the vast need — and the potential payoff in reduced recidivism — mental health and substance abuse treatment for many Massachusetts inmates is chronically undermined by clinician shortages, shrinking access to medication, and the widespread use of segregation as discipline. The prison environment itself is a major obstacle to treatment: In a culture ruled by aggression and fear, the trust and openness required for therapy are exponentially harder to achieve.

And when their incarcerations end, many mentally ill and drug-addicted prisoners are sent back into the world without basic tools they need to succeed, such as ready access to medication, addiction counseling, or adequate support and oversight. Such omissions can be critical: The Harvard-led Boston Reentry Study found in 2014 that inmates with a mix of mental illness and addiction are significantly less likely than others to find stable housing, work income, and family support in the critical initial period after leaving prison, leaving them insecure, isolated, and at risk of falling into “diminished mental health, drug use and relapse.”

That revolving door is enormously expensive, sweeping thousands of released inmates back into jail and prison and adding tens of millions of dollars to state budgets. Keeping even a single person out of prison saves the state more than $50,000 a year.

Yet at that precarious moment when an inmate with mental illness reenters the world — vulnerable and in urgent need of support — he or she has little hope of assistance from the state Department of Mental Health. Last year, 90 percent of the estimated 6,000 inmates with mental illness who were released from jails and prisons got little or no help from DMH as they tried to find treatment in the community, according to numbers provided by the state. Inmates like Nick Lynch don’t even apply for DMH help; their conditions aren’t considered serious enough under state criteria.

Limited by longtime public and legislative indifference, Massachusetts prisons have struggled to adopt the long view when it comes to spending on mental health care. Some national studies have ranked Massachusetts above average for prison health care spending, but the department’s own consultants concluded in 2011 that it could not fairly be compared with other states because of its unusually extensive — and expensive — mandate, including care for civilly committed patients at the state detox center and at Bridgewater State Hospital.

When those extra costs were set aside, the consultants found, Massachusetts’ health care spending on its 10,000 “regular inmates” was among the lowest in the nation, at $6,000 annually. The consultant, MGT Inc. of Texas — hired by DOC to recommend money-saving changes — warned that “further additional significant savings . . . are unlikely for this population.”

Still, the state kept cutting: Spending on mental health care in the prisons fell by 20 percent after the Texas study, from $18.9 million in fiscal 2013 to $15.2 million in fiscal 2014, according to DOC data.

Part of the savings came from drastically reducing prisoner prescriptions, targeting medicines with abuse potential — medicines that are also, for some patients, the most effective at controlling symptoms — and largely ending treatment for ADHD. From 2010 to 2015, prison mental health providers reduced the average number of inmate prescriptions by 35 percent, including a two-month period in 2010 when DOC officials said a “rigorous quality assurance review” allowed them to eliminate some 2,000 prescriptions they deemed unnecessary.

Some experts say such sweeping cutbacks, especially for inmates with ADHD, can increase disruptive behavior and, perversely, the use of segregation as punishment.

Short-changing care has other consequences: unreasonably heavy caseloads for clinical staff at some prisons, which strictly limit the care each inmate gets, according to a dozen current and former prison mental health clinicians who spoke to the Globe. The full-time mental health staff in the prisons is 25 percent smaller now than in 2012, though the number of inmates in treatment is similar, state data shows.

In a startling illustration of the work overload, seven of 15 prisons in Massachusetts are federally designated “health professional shortage areas” in the realm of mental health, meaning they exhibit “extreme need” for more clinicians and employ fewer than one psychiatrist per 2,000 inmates.

Three former clinicians and a former clinicial supervisor said some state inmates who need long-term help do not get it because supervisors resist adding patients to the already crushing caseload, sometimes refusing repeated requests. Instead, they said, clinicians are encouraged to provide treatment only when an inmate asks for it by submitting a “sick slip” — a practice that results in less consistent care.

“You’re encouraged to keep [case] numbers low,” said Patricia Stacy, a licensed clinical social worker who worked at Souza-Baranowski prison for more than three years. “Inmates will say, ‘What do I have to do, cut myself to get an open[ed] case?’ ”

Stacy, who was abruptly fired last year, believes she lost her job because she pushed for inmates to get more and better treatment — and was vocal when she thought their care fell short. She filed a complaint with the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination, alleging retaliation by her employer.

Correction department leaders said they have not heard of supervisors restricting the mental health caseload, but they acknowledged that clinical decisions are made by the for-profit company that provides mental health care in prisons. State officials said only the company — known as the Massachusetts Partnership for Correctional Healthcare, or MPCH — could provide details on care.

But MPCH, in turn, referred all questions about the care it provides back to state correction officials.

State officials could not definitively explain the $3.7 million drop in mental health care spending that occurred from 2013 to 2014, the period when MPCH was taking over mental health care in the prisons. They hypothesized that savings resulted from the move to a single vendor; previously, the prison system used separate contractors for mental health and medical care.

Yet, even as they said they lacked details about inmates’ treatment, prison officials defended a treatment system they said rivals any other state’s.

“It’s about getting the right person in the right program at the right time — that really is the best way to use your limited resources,” said Chris Mitchell, assistant deputy commissioner of reentry, who oversees efforts to prepare DOC inmates for release.

The prisons have acknowledged the need for more specialized care, creating a handful of separate units to treat inmates with serious mental illnesses. By most accounts, those units represent a major step forward. But altogether, specialized mental health treatment units in the 15 Massachusetts prisons have space for 285 inmates — 10 percent of the 2,900 with diagnosed mental illness, and less than half of the 725 whose illnesses are designated as serious by prison officials.

Those who don’t make it into those special units get minimal care: one therapy session per month with a clinician who might be juggling 50 or more other cases; a brief check-in with a psychiatrist four times a year; and maybe — for those not suspected of faking symptoms to get pills — a prescription from a limited list of medications.

A similar shortage of care seems to exist for addiction, which is rampant in prisons. State corrections officials say at least 65 percent of state inmates — at least 5,000 men and women — suffer from substance use disorders. Yet they maintain only 641 specialized beds for addiction treatment. They say that is plenty, and that inmates who want help receive it. Several prison mental health clinicians strongly disagreed, questioning the quality and availability of treatment.

A study this year by the Council of State Governments Justice Center found 22 percent of DOC inmates released in 2015 had no access to addiction treatment before leaving prison. Of those who did have access in one nine-month period, fewer than half actually received it: 39 percent refused help and 17 percent enrolled but did not finish.

Untreated addiction interferes with inmates’ mental health treatment, and it hurts their chances when they are released, said Dr. Jeri Walker, a psychiatrist who treated state inmates for five years.

“If you don’t address it, and then you release them,” she said, “what are the chances they’re going to stay clean?”

Long before he got locked up — when he was just a kid — Nick Lynch was already struggling with his mental health. His parents’ marriage was failing. He was always in trouble at school. When he was 8 years old, his mother sought help for him at a psychiatric hospital for children. At 10, he was so disruptive he was often suspended from school.

“He has more potential than he is showing,” the principal wrote in a note saved by his dad. A month later in school, Nick drew a picture of a person with a noose around his neck, the words “Shoot Me” written on his shirt.

His first diagnosis, as a child, was ADD, attention deficit disorder. Hospitalized again at 14, he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, his father said. A doctor prescribed new medication, but Nick loathed the side effects and stopped taking it. He started smoking marijuana instead. He tried living with his dad in Florida, but he got kicked out of school for selling weed.

“The decisions you make now will affect the rest of your life,” his father told him.

Come on, Nick thought, dismissing the warning. I’m only 16.

Years later, both of them would look back at that moment, finally understanding its full portent. In a series of interviews last year, Nick Lynch was reflective about the path he’d chosen, keenly aware of the burden it placed on his family and deeply remorseful for the pain he’d caused them. Looking back on his younger self, he said, felt like he was looking at a different person.

His school expulsion at 16 was only the beginning. At 18, he was jailed for armed robbery and assault with intent to murder, after he pointed a gun at three men in a car and robbed them of $100. He pleaded guilty; a judge sentenced him to six to eight years in state prison.

Nick was shipped around the prison system, making stops in Concord and Walpole before landing at maximum-security Souza-Baranowski. Along the way, he says, he got little mental health care, and faced skepticism from clinicians about his symptoms, which he says included bouts of crippling anxiety and paralyzing depression. Use of medication was discouraged, says Nick; when he did get some, it usually made him feel worse. Interactions with clinicians typically consisted of one- or two-minute checks on his well-being. Eventually he gave up, he says, and stopped asking for help.

Instead, he gave in to rage and fear, getting into frequent fights with other inmates. He hit first and hardest because he thought it kept him safer: “You don’t want to be the person on the floor not moving.” Punished constantly for his aggression, he says he spent months alone in segregation, until he could barely tolerate being around other people.

Suicide — once a shadowy and distant possibility — became real to him, vivid and familiar. Half a dozen of his friends hanged themselves or overdosed in prison, including the man who had showed him the ropes when he first got to Walpole. At times, Nick contemplated death himself. But he learned to avoid being placed on suicide watch, which meant isolation in a dark and filthy cell, without pen or paper, soap or socks, he said. Sometimes his “brain felt sick,” but he kept quiet: “If you say you’re hurting, they’ll punish you for it,” he said.

He reached a breaking point in 2010 after a brutal fight with another inmate, so bad that the man he’d beaten was sent to a hospital. When it was over, Nick could not contain his despair: He turned on himself and bit off part of his own wrist.

Still, the pain he felt was not enough; his self-destructive desperation crescendoed. The next day, Nick tried to hang himself.

He blacked out, he says, and an officer cut him down, “deep ligature marks” etched into his neck, according to records. Sent to Bridgewater State Hospital for evaluation, Nick says he was enraged and disgusted by abuse and filth he saw there, and soon got in yet another fight. Bridgewater shipped him back to Souza-Baranowski, concluding that he was not sick enough to stay.

That was when the prison’s treatment of him changed, Nick says: His mental health became a matter of concern. A prison psychiatrist prescribed two medications, Wellbutrin and Neurontin, that Nick believes finally quieted his anger.

“I’d showed them something they hadn’t realized about me,” he said of his suicide attempt and self-mutilation. “That’s what it took to get on medication.”

Nick had not arrived in prison with that damage. But he would take it with him when he walked free two years later.

If you tried to design an environment where mental illness would thrive, you might end up with something much like jail or prison.

Inside the state’s 32 jails and prisons, inmates are largely deprived of contact with family and friends. They spend little time outdoors or engaged in productive activity. Violence erupts without warning, feeding a climate of unrelenting anxiety.

In such a setting, security comes first. Cynicism seeps into the culture. Even clinicians who believe deeply in treatment for prisoners acknowledge the towering roadblocks to its success.

“To provide good mental health treatment in prison, in an environment ridden with anxiety — you just can’t do it. It’s the antithesis of the environment they need,” said Kristin Dame, a mental health clinician who spent three years as coordinator of a special treatment unit at Souza-Baranowski. “You can’t adequately treat someone for abuse when they’re still living with their abuser, so how do you treat for trauma when they’re still living in trauma?”

Privacy, considered essential to effective clinical practice, is often impossible in prisons. In some prisons, inmates must talk with clinicians in clear-walled observation rooms, where everyone outside can see, or through a cell door as neighbors listen in.

Even in the units with the best available care, treatment is distorted by security demands. Inside the 19-bed Secure Treatment Program at maximum-security Souza-Baranowski, group therapy sessions take place in a room dominated by a semicircle of six imposing metal cages painted periwinkle blue, known as “therapeutic modules.” Each inmate is locked into his or her own cage for group talks — thick plastic spit shields between them — to eliminate the risk of violence. Even during outdoor recreation time, each inmate is locked into his own large metal cage.

Widely praised when it opened in 2008 as a treatment-based alternative to solitary confinement, the unit has more recently become a source of complaints from prisoners who say they are verbally abused there by some officers, said James Pingeon of the nonprofit watchdog group Prisoners’ Legal Services. That harsh treatment can threaten their tentative stability, he said.

All 12 prison mental health professionals who spoke to the Globe, in separate interviews, acknowledged the necessity of balancing clinical needs with security concerns. Each said they bring some skepticism to their evaluation of inmates’ complaints: Some prisoners do manipulate the system, faking symptoms to stay out of segregation, or to get medication they don’t need.

But many said that skepticism is taken too far by some clinical staff, leading some prisoners to be labeled as liars and cut off from help.

That indifference can be dangerous in prison, where the standard punishment for serious infractions — segregation — is known to make mental illness worse.

“Too often, inmates are placed in solitary confinement because of behavior related to their underlying mental illness and their histories of trauma,” said Lisa Newman-Polk, a clinical social worker at Souza-Baranowski from 2013 to 2014. “Sadly, solitary confinement often produces, or exacerbates, acute psychiatric symptoms. So these men often become unstable and symptomatic — and more prone to behavior that results in longer and more frequent stays in solitary.”

Joseph Vyce hanged himself at MCI-Cedar Junction at Walpole in 2014 after being sent to the Departmental Disciplinary Unit, or DDU, where inmates are held for long stretches in solitary confinement. Prisons had stopped sending inmates with serious mental illnesses into the extreme isolation of the DDU after a lawsuit and court settlement in 2012. But prison officials — warned by an outside doctor and concerned advocates before his death that the 35-year-old appeared to be too sick for the unit — insisted that Vyce suffered from substance use disorder, not a more serious mental illness, according to Prisoners’ Legal Services and a lawyer for Vyce’s estate.

It was only after his death that the advocates learned the DOC had access to his prior medical record, which showed he had a history of suicide attempts and had been diagnosed at least six times with bipolar disorder, a serious illness that should have barred him from the DDU. DOC officials declined to comment on his death, citing the pending litigation.

“He was my flesh and blood, and they treated him like trash,” said his mother, Lorena Vyce, 61, who is moving forward with a lawsuit against the prison, according to a lawyer representing her son’s estate. “He was outgoing. He wanted life. That’s why this has been so hard to believe, that he could get to so dark of a place.”

Some clinicians and advocates contend there is a pattern in the prisons of diagnosing inmates with less serious mental illnesses — which cost less to treat, and don’t require special housing or discipline — even when symptoms and history indicate greater severity. DOC officials said that practice has never been observed or reported, calling it a “license revokable” violation of ethics.

Despite the limited number of specialized mental health beds in the prisons, corrections officials said there are no more than a handful of inmates on waiting lists. On a tour last summer, one such area — the Residential Treatment Unit at Souza-Baranowski prison — was more than half empty, with 34 unoccupied beds and 26 prisoners in residence.

“We’ve got the vacancy light on, but there aren’t many who meet all the criteria,” said an official on the tour who explained that inmates prone to violence cannot be housed there.

DOC officials later disputed the employee’s assessment, saying behavior issues never override an inmate’s need for placement. If beds are empty, they said, it means there aren’t inmates who require that level of treatment. They stressed that care in special units is not always best, especially to prepare inmates for life outside prison. “We want [inmates] practicing and rehearsing how to manage their illnesses in the community,” said Mitzi Peterson, DOC’s director of behavioral health.

Just 40 of the 400 inmates receiving mental health treatment at Souza-Baranowski on that day last summer were housed in its two special treatment units. The rest coped with their illnesses in the regular cell blocks, or in segregation, where Nick Lynch said he spent years alone with his symptoms.

“When you’re in that [segregation] cell, and you know you can scream and scream and nothing can get you out . . . [I]t’s overwhelming,” he said.

Six weeks after he’d walked out the door of the prison in Shirley, Nick Lynch was trying to seem at ease, to make his dad happy and prove that he could make it. But the world that he’d walked into still felt alien. The strain of adapting was quickly becoming unbearable.

It was June 2012. He was working at a gym in Mashpee. The job was fine, but he felt constantly on edge, surrounded by people who knew nothing of his past. He worried what they’d think if they found out he’d been in prison. Afraid to be himself, unsure how to be someone else, Nick’s mind churned with anxious thoughts. Everyone around him seemed so young, products of a different, gentler world he barely knew.

Everything I’m going to say is going to scare you, he thought.

He shied away from conversation and kept to himself, segregated this time in a hole of his making.

At night in the small house his father had bought on the Cape — furnished in soothing neutral colors to ease his transition — Nick lay awake, unnerved by the quiet, unable to sleep without the prison’s clamor.

Nick had left prison with a limited supply of the two psychiatric medications he’d taken there, Wellbutrin, an antidepressant, and Neurontin, for his anxiety. He needed to see a psychiatrist to get new prescriptions. His father, who had contacted prison staff months before his son’s release, says they did not offer to find a psychiatrist for Nick, so he did it himself. Prison records mention the need to arrange mental health care, but the notes do not identify an outpatient health provider until the day before his release — and only after an entry detailing his father’s involvement.

But when Nick showed up for his first appointment at Gosnold, a treatment center on the Cape, he was told he would have to meet multiple times with a therapist, who could not prescribe medications, before he could see the psychiatrist who could, according to Nick and his father.

When his supply of medication from prison ran out, Nick and his dad say, the Gosnold therapist sent Nick to a hospital emergency room for a refill, rather than alerting the psychiatrist. The ER gave him a 10-day supply of antianxiety medication in mid-May, records show, but with a warning: Further requests would be considered drug-seeking behavior and would probably be denied.

Yes, Nick thought, I am seeking these drugs — because I need them.

His antidepressant was gone, never to be refilled. He was mostly without meds for his anxiety, too — except during a period of relief in June, when a nurse practitioner at a different health clinic in Hyannis wrote him a two-week prescription for Neurontin. Though he visited the federally funded clinic several times that summer for primary care, documentation kept by his father includes no record of any prescriptions during July.

He never saw a psychiatrist at either health center, Nick says. It is not clear that any coordination linked his treatments — medication in Hyannis, therapy in Falmouth. No one managed his withdrawal symptoms when his pills ran out, the family says, or raised concerns about his risk of drug abuse.

His patchwork care was not unusual, according to the veteran defense attorney who represented Nick in his most recent case. In years of work with incarcerated clients, Rosemary Scapicchio said she has seen the same breakdowns in oversight and treatment derail newly released inmates again and again.

“There’s no bridge,” she said. “There’s no one to say, ‘Go here; do this.’ . . . And then the pills are gone, and they’re trying to figure it out.”

Ray Tamasi, president of the Gosnold center, acknowledged that Nick’s care in 2012, as Nick and his father described it, seemed to have inadvisably delayed the young man’s access to a psychiatrist who could have reviewed and renewed his prescriptions. New patients are often assessed by a therapist before seeing a psychiatrist, he said, but those who come in already taking medication should gain access to a doctor without long delays.

“It sounds like we could have done better, to get him to the psychiatrist sooner,” said Tamasi, “but there is sometimes overwhelming demand for these services.”

He said Gosnold now employs recovery coaches who partner with patients coming out of prison, jail, or detox to help keep their stressful reentries on track. Had such coaches been available when Nick was released, it might have provided oversight he lacked.

Instead, Nick bounced between appointments, hiding his fear and the longing he felt to escape it. In mid-June, he attended his younger sister’s wedding. The stress of facing his extended family — all of them wondering whether he would make it — heightened his anxiety, he said. He drank and smoked marijuana to soothe his nerves, violating the terms of his probation.

As his access to medication grew tenuous, Nick tried to take the entrance exam at Cape Cod Community College. Halfway through the test, he panicked and fled. It wasn’t the questions that scared him, he says, but the computer he did not know how to use. Staring down the strange machine, he felt a pang of need: I’ve got to have my medicine, he thought, so I can do this.

A few days after he ran from the exam, someone from the college called and urged him to try it again. The next time, he finished and passed, earning close to maximum scores in the sections on reading and language.

Nick wanted to take business classes, to build a life like his best friend Brian Diaz had. As kids, he and Brian had run wild together, Nick says; they had gone to prison days apart, for unrelated offenses. After Brian got out, a few years before Nick, he had owned his own successful barber shop in Worcester. Brian seemed to have put his past behind him — it made Nick aspire to his own success.

But other old acquaintances of Nick’s were selling drugs. Any day that summer of 2012, he was one phone call away from an illicit pill that would erase all the fear and pressure.

His yearning for relief increased every day, a river of longing that finally swept him away. Nick says he had never taken drugs outside of jail, but now he craved them: heroin, painkillers, “whatever would make me feel better. . . . It seemed like the only way that I could function.”

He didn’t tell his father, but he spoke of feeling damaged. “People don’t realize,” his dad remembers Nick saying that summer, “the person who went into prison was much better than the person who came out.”

Kevin Lynch didn’t guess that Nick was using drugs, although the signs were there. His son was disappearing for long stretches, leaving him to shingle the house on his own. He confronted Nick about it, and they fought. One night in early August, eating dinner with his dad, Nick seemed far away, staring and smoking in silence.

He said he couldn’t stay; he had to be somewhere.

He hugged and kissed his father. Then he disappeared into the darkness.

Not everyone thinks inmates deserve good mental health care — or any kind of health care, for that matter. “The view is that they’re criminals and they don’t deserve it,” said Pat McCarthy, longtime health service administrator at the Hampden County Correctional Center in Ludlow.

McCarthy sees the danger in that thinking: “The less we do here, to stabilize and treat them,” he cautions, “the less prepared they are to go back to the community.”

County jails and houses of correction hold about half the state’s 20,000 inmates; they are 17 separate kingdoms, run by 13 sheriffs. At the Worcester County jail, where Nick Lynch spent much of last year — and where a Department of Justice investigation found serious failures in mental health care in 2008 — officials have doubled the clinical staff in three years, to 10 full-time positions, added new private rooms for counseling, and incorporated training for correctional officers about their own, often neglected mental health issues.

“The need is tremendous,” said superintendent David Tuttle, who oversees 1,100 inmates, half receiving treatment. “We all need to take a good honest look at how we handle these people, when they’re here and when they leave.”

Still, the widespread recognition of the need often fails to inform policy and practice. Many county jails routinely send inmates home with just a week’s supply of medication — or none at all. Staffing is erratic: Essex and Hampden counties each house around 1,500 inmates, but Essex has four mental health clinicians, while Hampden employs more than 50, according to a survey conducted for the Globe by the Massachusetts Sheriffs’ Association.

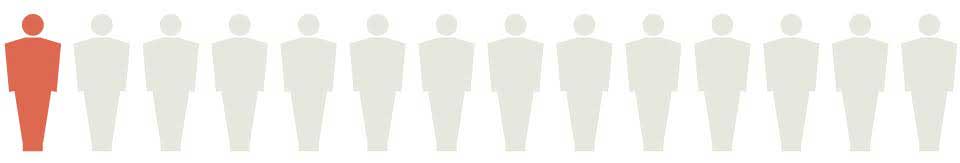

As of December 31, there were 3,012 open mental health cases among county inmates in Massachusetts. But only 216 inmates—7 percent—were Massachusetts Department of Mental Health clients.

For every 14 inmates with mental illness, only one had access to a full array of state services.

Patrick Garvin/Globe Staff

Patrick Garvin/Globe Staff

SOURCE: Massachusetts Sheriffs' Association; county correctional facilities

In Norfolk County, Sheriff Michael Bellotti has been waiting since 2007 to transform inmates’ mental health care. That’s when the Legislature granted initial approval to his plans for a two-story, regional mental health center to improve upon the jail’s cramped medical unit.

Nine years later, the project has yet to be funded.

“We’re doing the best we can,” Bellotti said. “This is the hand we were dealt, and we’re dealing with it.”

More than a century ago, outraged Americans took action to stop the use of jails and prisons as mental health asylums. In the mid-1800s, after the number of mentally ill people incarcerated nationwide reached record highs, a national campaign succeeded in moving tens of thousands of them to psychiatric hospitals. The shift was no panacea — some hospital patients suffered abuse and neglect — but access to treatment improved. For a century afterward, until 1960, people with mental illness largely disappeared from the nation’s prisons, according to a recent report by the Pioneer Institute.

Then, in the middle of the 20th century, the public turned against mental hospitals, appalled at the wretched conditions some offered and optimistic that patients could live better lives in the community. But as Massachusetts shut down most of its psychiatric institutions, people with severe and chronic mental illnesses again flooded police stations, courtrooms, jails, and prisons. Year by year, as the state fails to construct a robust, fully functioning community care system, more of them end up incarcerated.

Jails and prisons, never designed for any therapeutic purpose, have become the new asylums.

Yet even the compromised care prisoners get while locked up may be better than what awaits them on the outside.

As correctional facilities, hemmed in by budget constraints, prepare mentally ill inmates for release, the Department of Mental Health sends its 10-member Forensic Transition Team to help arrange treatment back in the community. But the system that awaits them there is threadbare and stretched thin — and available to just a few of those who need it.

Stymied by a state budget that has been shrinking for years, DMH reserves its full array of services only for those it accepts as “clients.” To gain access to state resources including caseworkers, day programs, and housing, people with serious mental illness must navigate a demanding application process — and only the sickest who apply win approval. Among all Massachusetts adults, a population including an estimated 216,000 people with a serious mental illness, only 21,000, about 10 percent, are DMH clients with full access to treatment and support.

No one needs those structures more than inmates returning from prison. And when they are missing, people like Nick Lynch fall through the cracks.

Kevin Lynch closed his eyes and prayed it might be a mistake: His son Nick, the caller said, had been arrested that morning. A drug deal in Marshfield had turned volatile; a bullet had pierced an apartment wall. Police had charged Nick with attempted murder.

It was Aug. 6, 2012. Numb with grief, his father did the math, calculating the velocity of their failure: 103 days had passed since Nick’s release from prison.

Locked up in the jail in Plymouth County, Nick sent agonized apologies to his father. “The drugs made my mind work in a different way and without them I was a ball of anxiety and sickness,” he wrote. “I am so sorry I hurt you Dad. . . . You did all you could. I love you more than anything.”

Kevin Lynch avoided the small, gray-shingled house where Nick had lived for those three months and two weeks. He dreaded going inside to pack up his son’s things; that, he knew, would make the bitter loss more real. Swallowed by depression after Nick’s arrest, his father tried to fight it off, then gave in and sought treatment.

The family’s hopes would flare again, when the new charge against Nick was dismissed. But the young man had stumbled and would not regain his footing. A judge sent him to a drug treatment program in Worcester; ominously for Nick — and for others with addictions tied to mental illness — it did not allow psychiatric medications. Nick lasted five months before he failed a drug test, violating his probation.

Then his best friend, Brian Diaz, hanged himself in the Worcester jail, after being found with drugs and sent to segregation. He was 29, with 2-year-old twin daughters.

Brian had been like a brother to Nick, and a hopeful example, but Brian, too, had slipped back into old habits. Facing a return to jail, he had been distraught. But when Brian spoke of suicide, Nick could not imagine he was serious.

Brian had too much to live for, he’d thought. Brian would never do that.

The death of his closest friend devastated Nick.

“I never lost something that I loved that much,” he said.

Three weeks after Brian died, consumed by grief and guilt, Nick OD’d and medics revived him with Narcan. Out with friends in Worcester hours later, he joined a late-night bar brawl that badly injured two people. A video showed him outside the club, kicking a man on the ground.

The new charges against him, for aggravated assault with a dangerous weapon and assault causing bodily injury, guaranteed that Nick would be locked up again for years.

He was held, awaiting trial, at the Worcester jail, where he’d first served time when he was 17. Some of the officers remembered him, the angry, skinny kid he’d been back then, at the start of his journey through the prison system. Closing in on 30 now, a seasoned prison elder, Nick stayed out of fights, and out of segregation, mostly. He asked for the meds that had helped him before, but his request was rejected.

As part of the standard procedure as he reentered the system, a prison clinician in Concord reviewed records from Nick’s previous incarceration. She found he had been classified, in 2011, as seriously ill — warranting two or more clinical visits per month — but in practice, in the year before his release, he got less intensive care: “Monthly contacts were considered sufficient,” she noted.

Over and over again in his mind, Nick replayed his 103 days of freedom, lingering on each decision he wished he could change.

“I needed to fix my brain like I needed water to live,” he wrote to his father in 2014. “I didn’t know I [had] developed a drug dependency but I did. . . . The anxiety was so bad. It was a way to cope and I fell for it.”

He could feel himself deteriorating again. “My brain and will used to be strong Dad,” he lamented, “but instead of growing stronger through my prison experience I grow weaker.”

When weeks passed and Nick didn’t call, his dad assumed he was back in segregation. With that silence came the unspeakable fear: that his son would try to kill himself again.

Kevin Lynch tried to channel his fear into action. He earned a degree in health care policy and lobbied lawmakers on Beacon Hill for better mental health care statewide. He established the nonprofit Quell Foundation to help people like Nick, and he gave away $50,000 in college scholarships to students whose lives had been touched by mental illness.

There was so much that needed to be done — and so little he could do to help his son.

In July of 2015, Nick assaulted another inmate, a man he blamed for his friend Brian’s suicide. Nick was sent to segregation for 15 days; by August, his mental health was in steep decline. He’d stopped taking Remeron, the antidepressant they’d given him, because of side effects including weight gain. With mounting desperation, he asked his father to help him.

At his father’s request, the jail agreed to let a doctor from outside examine Nick. The psychiatrist recommended two medications, including Wellbutrin, the antidepressant that had helped Nick in the past. He says jail clinicians told him they could not prescribe either one; Wellbutrin and other commonly abused medications are rarely given in jails and prisons, and usually only after other drugs fail to help, especially to inmates with histories of addiction.

Nick was not alone in his frustration. The phaseout of Wellbutrin has adversely affected numerous prisoners who felt no other medicine helped them, said Tatum Pritchard, an attorney with Prisoners’ Legal Services who has assisted several men with their requests for the medication.

One prisoner who had his longtime Wellbutrin prescription canceled was given other meds that made him stutter so badly he could barely speak, Pritchard said, while another became suicidal when he was switched to Lexapro. Advocates question why abusable medications can’t be crushed and put in water for inmates to drink, preventing them from “cheeking” pills to sell later. But some clinicians say the meds don’t work as well that way — and that even crushed medication can be salvaged for sale or abuse.

Prisoners “suffer for years and years just because someone put their medication on a different list,” Pritchard said. “It doesn’t make any sense.”

Nick felt desperate, but he knew that others had it worse.

At least he would be released again. Someday.

Late in October of 2015, Nick was finally sentenced to three to four years in prison for the bar assault. Afterward, his father slipped out of the courtroom and into the hallway. A towering man, 6 feet 4 inches tall, he stood alone with his head bowed in grief, unable to speak.

Nick was sent to the state prison in Walpole, where he says clinicians would not give him Wellbutrin. He asked for it again early this year, after being transferred to Old Colony Correctional Center in Bridgewater, a medium security prison designated as a center for mental health treatment. A supportive doctor filed a special request, but the request was denied, Nick says.

He opted to go without medication, again. Before long he was back in segregation. Then he was sent back to Souza-Baranowski, the maximum-security prison where he’d once attempted suicide.

Every November, as his son’s birthday approaches, Kevin Lynch buys Nick a birthday present. He packs away each perfect gift — among them, a football signed by six New England Patriots — in the boxes he stores in his attic, tucked in with Nick’s childhood baseball cards and the historic front pages he saves for his son: the 2004 Red Sox World Series win; Obama’s 2008 election; bin Laden’s death in 2011.

The dusty collection holds a message for his son: I was thinking of you, always. I did not forget.

On one box, a note is printed in red pen: Nick, I will save this for you forever.

He expects his son to get out of prison sometime next year.

Contact the Spotlight team

- Tipline 617-929-7483

- Email [email protected]

- Twitter @GlobeSpotlight