The desperate and the dead: courts

‘I can’t take it anymore’

A courtroom suicide shows the court’s unpreparedness to deal with mentally ill defendants.

LOWELL — Debra Silvestri slipped into the women’s bathroom at the district courthouse, pulling a plastic bag full of sedatives and antidepressants from her purse. Her lawyer had just told her the judge was thinking of sending her to a women’s prison because a court-ordered test showed she had been drinking.

For more than a year, the 55-year-old mother of three had come nearly every week to the Lowell Drug Court, a requirement of her probation following a 2012 drunken driving arrest. It was supposed to be a compassionate alternative for addicts such as Silvestri, a place that steered them away from jail and toward treatment.

But Silvestri had other problems that made drug court painful for her. She had struggled for years with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, once cutting her wrists and wandering the streets of Tewksbury, knocking on neighbors’ doors in the middle of the night.

Yet, court officials rarely asked Silvestri about her mental health. Instead, they focused on making sure she attended AA meetings, took random drug tests, and breathed into a machine that can detect alcohol use. Her life had turned into a succession of court-ordered deadlines that made her so anxious her hair had started falling out in clumps.

“I can’t take it anymore,” Silvestri often told family members.

On that afternoon in court in September 2015, Silvestri was terrified. Judge Thomas Brennan, a former prosecutor, sent at least half the people who came before him back to jail, usually for relatively minor probation violations like drinking or taking drugs. Silvestri was sure she would be next.

She emerged from the restroom. On her way into the courtroom, she saw her aunt, who had driven her to court that day.

“I don’t think I’m coming home with you today,” Silvestri said, kissing her aunt on the cheek. “Tell the kids I love them.”

Then, she took a seat at the front of the courtroom. One hour into the session, she slumped over, eyes closed. Two women sitting next to Silvestri grabbed her to keep her from falling to the floor.

An ambulance rushed her to Lowell General Hospital, a powerful mix of tricyclic antidepressants and sedatives in her veins.

By the time the vehicle pulled up to the emergency room, it was too late. The medical examiner ruled her death a suicide.

People like Deb Silvestri have been streaming into Massachusetts courtrooms in growing numbers since the early 1970s when the state began closing psychiatric hospitals, leaving more and more patients to fend for themselves and often find trouble with the law.

The trend became obvious to front-line court officials as they confronted a stream of defendants who were eerily silent, suspicious, quick to anger.

“As time went by, it became more and more evident that we were dealing with more and more people with mental illness,” recalled Bernie Fitzgerald, who started his career as a probation officer in Dorchester District Court in 1971.

The courts weren’t ready for this onslaught, and they still aren’t today. An examination by the Globe Spotlight Team finds that here, as at other levels of government, the state lags badly in its services and solicitude for defendants with mental illness. Massachusetts’ court system ranks among the worst in the country at providing specialized services for people with mental illness and keeping them out of prison or jail, where they often suffer emotionally and get subpar treatment.

Court personnel are, in the main, poorly equipped to deal with those with mental illness. Judges, probation officers, and lawyers alike admit they often lack the expertise, the resources, or the time to help people whose conditions can be hard to diagnose and can complicate the assessment of their intent in alleged criminal acts.

The state has been slow to launch special courts designed to address these defendants’ circumstances and needs. That consigns many of those with mental illness to regular courts or sessions designed primarily to deal with defendants addicted to drugs.

“I don’t think we as a court have a sophisticated understanding or protocol when it comes to dealing with people with mental illness,” said Judge Mark Coven, the first justice of the Quincy District Court, one of the few in the state to hold sessions specifically for defendants with mental illness. The Legislature this year turned down funding for more.

The Trial Court doesn’t even keep track of how many people with mental illness are among the approximately 200,000 criminal cases that pass through the courts each year. The total almost certainly runs to the tens of thousands, given this rough benchmark: At least 30 percent of defendants committed to prisons report having mental illness. And jails report that 10 to 40 percent of inmates are on medication for a mental health condition.

The courts and the state’s Department of Mental Health do spend millions of dollars on psychiatrists and other mental health services — about $18 million in fiscal year 2017 — but half the money is spent on juveniles and on the approximately 2,000 adults whose symptoms are so severe that a state-paid specialist must assess their competence to stand trial.

That leaves few resources for the far larger group of defendants with serious mental illness who are deemed competent to stand trial but are not sick enough to be hospitalized.

As a result, the majority grind through a system with few options available to address their underlying health problems, and, all too often, people in need of mental health care are instead sent to jail.

Consider Jarrod Harlow, a young man with a long history of mental illness, including bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder, who was jailed for five months while awaiting trial for a hoax bomb threat to the town of Acton in 2015. Harlow said he was harassed by other inmates, wept every morning, and began banging his head and hurting himself to the point that jail officials called his lawyer and implored her to get him out of jail.

A judge eventually agreed that Harlow was incompetent to stand trial. That cleared the way for him to be released from jail and sent to a hospital.

Or take the case of a 22-year-old Marlborough woman with psychiatric disorders, who rotated in and out of hospitals until she was incarcerated for six months for assaulting a police officer and breaking and entering in 2015. Her behavior in MCI-Framingham became so alarming — bashing her fists against the wall and threatening to kill herself — that prison officials sent her temporarily to a state hospital. “Her current psychiatric illness cannot be managed in the prison setting,” a prison official wrote to the Marlborough District Court.

And then there’s Rosa Alicea, a 66-year-old Lawrence woman apparently afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease — a neurological condition which can present symptoms akin to mental illness — who spent two weeks at MCI-Framingham for bringing a gun into a courthouse in September 2014. She had found the weapon outside her apartment and forgotten that she put it in her purse, but prosecutors said she was too dangerous to be released. A social worker assisting the defense and Alicea’s daughter helped convince the judge she did not belong in jail, but she still spent six more weeks in a locked hospital ward before being released.

In sum, the courts, like police departments, prisons, shelters, emergency rooms, and beleaguered families, are left to deal with a crisis of care for people with mental illness that the state has largely failed to address.

“The criminal justice system is the system that takes over when all other systems have failed. We’re the last resort, and we’re left to pick up the pieces,” Suffolk District Attorney Daniel F. Conley said.

A defense attorney who has represented many clients with mental illness said courts are being asked to do a job for which they are poorly suited.

“The appropriate venue is, of course, mental health care facilities, with case managers, with a system that can monitor them while they’re at home, at work, at school,” said Bill Lane, a public defender who works in courts around Boston. “We’ve destroyed that in this state. We’ve opened the drain plug, and that has led to the courts.”

Most states that have addressed the problem with energy and sufficient resources have moved to create a system of specialized courts tailored, in their tone and enforcement methods, to the sensitivities and needs of offenders with mental illness.

Research increasingly shows the benefits: One study in Utah found that graduates of such courts are 22 percent less likely to commit new crimes. In New Hampshire, officials say mental health courts have kept 80 people in one county out of jail, for an estimated annual savings of about $2.24 million.

But despite the significant potential benefits and savings, Massachusetts lags badly on this front.

There are just seven mental health courts here, sufficient to address the needs of just 17 percent of the state population. Utah, meanwhile, has opened 12 mental health courts, enough to serve 85 percent of its population. And New Hampshire, with a population five times smaller than Massachusetts, has 10 mental health courts.

Nearly 600 criminal defendants attended mental health court in Massachusetts between June 2015 and May 2016, state figures show, but thousands more might have benefited if more sessions had been available. The specialized court was never an option for Silvestri because the nearest one was more than 20 miles away — too far for someone whose driver’s license was suspended after a drunken driving arrest.

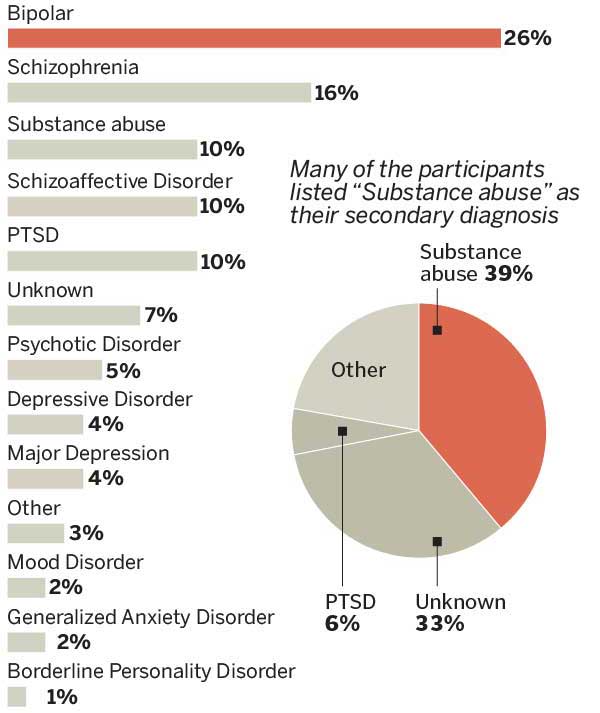

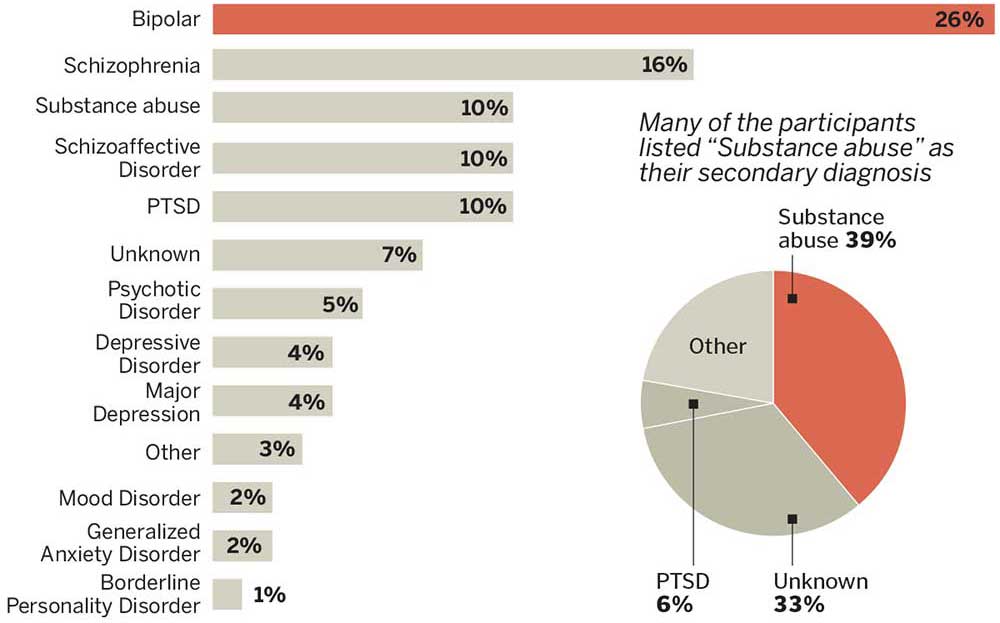

Diagnoses of people using mental health courts.

Two diagnoses were recorded for each individual using mental health courts. The Globe calculated the percentage of people who listed each condition as a primary diagnosis.

Note: the Department of Mental Health provided to the Globe preliminary data from 572 people whose cases were heard in Massachusetts mental health courts from June 2015 to May 2016.

The nonprofit Treatment Advocacy Center, which analyzes how each state’s criminal justice system treats defendants with mental illness, in 2013 ranked Massachusetts 39th in providing access to mental health courts and gave Massachusetts a failing grade for efforts to keep people with mental illness out of jail.

Trial Court Administrator Harry Spence had talked about an ambitious expansion of the mental health courts early in 2015, but the Trial Court opened only onethat year, in Quincy.

The Trial Court pushed for an additional $2.8 million to open seven more specialty courts in 2017, but the Legislature provided only enough to maintain the current 41 specialty courts, most of them drug courts.

Spence said the evidence for the effectiveness of mental health courts is less conclusive than for drug courts and that the latter have to be the state’s priority because of the deadly opioid epidemic.

But if evidence for the comparative effectiveness of mental health courts is what is required, Massachusetts has done little about it. Courts here have not even gathered the data that could quantify the state’s need for mental health courts.

Since May 2013, probation officers have been asking felons on probation about their mental health, said Edward J. Dolan, the state’s commissioner of probation, but the information was still in “paper and pencil” form as of September 2015, making it virtually impossible to analyze. A year later, the courts had yet to convert the data into electronic form.

Many defendants with mental illness end up in drug courts by default because people with mental illness frequently struggle with substance abuse as well — in many cases, turning to drugs and alcohol to ease their symptoms. In Lowell drug court, 26 of the 41 participants whose cases were examined by the Globe had been ordered to undergo mental health treatment as a condition of remaining in the program.

State officials say drug courts can handle this caseload effectively. After all, mental health and drug courts have a similar mission: give participants a chance to stay out of jail by accepting and complying with court-supervised probation and mandated treatment.

But drug and mental health courts are not interchangeable. Drug courts rely on a heavily structured process, including regular testing for drug and alcohol use. In mental health court, by contrast, drug testing is not a mainstay, and there are more likely to be clinical workers who can help a defendant find treatment and therapy.

Deb Silvestri’s family questioned whether Brennan and other court officials in Lowell were aware of the severity of her mental illness, that she heard voices and worried police were spying on her through the cable TV line running outside her Tewksbury apartment.

“I wish they’d gotten her the psychiatric help she needed,” Silvestri’s mother, Joan Silvestri, said. “Debbie reached her breaking point.”

Silvestri was not ordered to undergo mental health treatment as part of her probation, court records show. But during a drug court session three months before her suicide, Brennan asked Silvestri whether she was still seeing a mental health counselor, according to a recording of the hearing.

She told him yes.

In an interview, Brennan declined to discuss what he knew of Silvestri’s mental health, but he said the courtroom suicide affected him deeply.

However, he said her death did not make him reevaluate how he runs the court.

“I don’t think there was anything that occurred . . . that would require any kind of change,” Brennan said.

It is important to provide appropriate compassionate support and services, he said, but also firmness.

“There has to be accountability,” Brennan said. “Unless you have accountability, [drug court] doesn’t work.”

Bridget Green prepared carefully for her last day in Roxbury mental health court.

For years, she had suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and an addiction to crack cocaine. She had been homeless, a victim of frequent beatings and robberies on the street.

The court staff had saved her life, she believed, and that cold morning in September, she wanted to look nice for them. She curled her hair, donned a new blouse and a pair of black slacks, and applied purple eyeshadow and plum-colored lipstick.

Green, 54, relies on a walker to get around because of her bad knees and back. But when Judge David Weingarten called her name that morning, Green eagerly bounded out of her seat and rushed to the front of the courtroom.

“How are you, Ms. Green?” Weingarten asked, smiling broadly.

“I’m excellent,” she said, beaming back. “I’m graduating!”

Green had been skeptical that mental health court would work for her. The idea of mandatory appearances before a judge every two weeks or so to explain how she was managing her mental illness and her addiction seemed unlikely to help. After all, she had gone to hospitals for help in the past, only to feel dismissed by the nurses and doctors and wait hours, if not days, for treatment.

She ended up in the court after a woman living in her group home accused her of stealing a purse. Green was thrown out on the streets. Her lawyer, Rebecca Kratka, persuaded Weingarten to accept her into the voluntary court program, where the terms were straightforward: comply with weekly drug screens, regularly visit a Roxbury center to help combat her drug addiction, and continue her therapy, according to court records.

If she kept up with these conditions, the larceny charge could be dismissed. If she failed, she could be terminated from the program and her case moved back to regular district court.

Green is like many other people who have passed through the state’s mental health courts. More than half of the 572 people who participated in the sessions between June 2015 and May 2016 said they have been homeless, according to preliminary figures from the state Department of Mental Health. Two-thirds also said they have struggled with drug addiction or alcoholism.

The first few months in the court were difficult for Green. Living on the streets made it hard to stay clean, and she repeatedly returned to using crack. Weingarten sometimes warned that he might have to send her back to regular court, but the judge never sent her to jail for relapsing. When he learned that she was still homeless, he urged a court clinician to help Green find a place to live. She was eventually placed in a residential program.

Green said it was the first time she felt someone cared about her.

“They give you a lot of praise. They make you feel like you can do it,” Green said. “They made me want to stay on my meds. They made me want to get clean.”

By August, after nearly two years of court supervision, Green was sober. She was living in a Dorchester house she had found on her own and visiting her therapist regularly. Everyone agreed she was ready to leave the program.

On her graduation day, Weingarten remarked on how far she had come and commented on her healthy appearance.

“This is the best I’ve ever seen you look,” he told her. “You fought for yourself.”

He dismissed her case, and Green pumped her fist. But she was not done yet.

She recited a poem she had written to the court, entitled “Friends ’Til the End.” Then she pulled a tiny speaker from the bag attached to her walker and plugged in her phone.

“I’m going to sing,” Green announced.

Green swayed her hips, snapping her fingers as she crooned Luther Ingram’s “(If Loving You is Wrong) I Don’t Want to be Right.” Weingarten leaned forward in his chair, smiling.

Deb Silvestri’s experience in the Lowell drug court could scarcely have been more different.

On the surface, Silvestri looked like a promising candidate for rehabilitation. When she was pulled over in 2012 for driving erratically — a partially empty vodka bottle peeking out of her purse — it was her first OUI arrest in nearly 20 years. But it was her third offense and, under state law, she would have to go to jail. She served six months on the initial charge but eventually was sent back to MCI-Framingham for drinking, a violation of her probation.

Silvestri was still in custody in June 2014 when she met Marie Burke, the state’s drug court coordinator, who invited her to join the voluntary program in Lowell.

Silvestri was desperate and hopeful the court could help her, her mother said.

“She wanted to overcome this,” Joan Silvestri said. “She knew she had to do something, and it was the only way of staying out of jail.”

But some judges’ relentless focus on substance abuse can make drug courts hard places to endure for those with mental illnesses. In 2015, one probationer with mental illness in Brockton chose to go to jail for 46 days rather than stay in the 18-month drug court program, after a judge told him that he would not be allowed to take the Neurontin he had been prescribed to treat his bipolar disorder because the drug is frequently abused.

Similarly, court officials in Lowell discouraged a 29-year-old food delivery worker from taking the same drug in 2015, even though he protested that his doctor had prescribed it for years to treat his mood disorder.

The Lowell court’s strict demand for accountability was especially stressful for Silvestri, who often told friends and family that she feared police would come to her door and arrest her. During the year Silvestri was in the program, at least 23 of 41 fellow probationers were sent to jail, largely for offenses such as relapsing or getting kicked out of treatment programs, according to a Globe analysis of court records. The stays in jail lasted anywhere from a few days to several weeks.

National standards for drug courts recommend jail only when participants are a threat to public safety or when all other measures have failed, and they recommend that detention last no more than five days.

But Brennan said drug court participants who relapse with drugs or alcohol need to be kept safe from themselves. Putting them in jail keeps them off the street and gives them time to think about their actions, he said. Last year, Brennan ordered one woman held for four weeks, through Christmas, after she told the court she had used heroin.

“I know some of the attorneys will say, ‘Get them into this program or a sober house.’ To me, that’s not what should happen,” Brennan said. “These are people who are in danger. You’re talking about people’s lives.”

Several lawyers who appear before Brennan are concerned about the court’s habit of incarcerating probationers instead of finding them better treatment, said Lynda Dantas, the attorney in charge of the Lowell District Court Office of the Committee for Public Counsel Services.

“We’ve got this court that is legitimately trying to help people, but they do not understand the depth of the problems,” said Dantas, who works in the drug court. “The court has no education in mental health diagnosis and treatment.”

Still, some probationers have thanked Brennan for his tough approach. During one session, a young woman named Kathleen who had been homeless and addicted to heroin credited the drug court’s strict structure for helping her get sober and find a job.

“Nothing about this has been easy, but it’s been worth it,” Kathleen said.

For months, Silvestri did well, too. She attended the court without fail and met all the conditions of her probation.

But in May 2015, court officials said a drug screen suggested Silvestri had been trying to fool the test. Brennan ordered her to breathe into a Sobrietor several times a day to prove she wasn’t drinking.

Silvestri worried the requirement would make things hard for her at her new job at Dunkin’ Donuts if she had to leave frequently to breathe into the machine.

“The sobrietor will give me a nervous breakdown,” Silvestri pleaded with Brennan. “Can you hold off just this one time? I’m begging you.”

Brennan held firm.

“That’s what’s going to happen,” he told her.

Judge Kathleen Coffey, who runs the mental health session in West Roxbury District Court, said many of the probationers in her courtroom have drug addictions, and relapses are not uncommon. But jail time is rarely the right penalty, she said.

“I don’t see that as the answer,” she said. “A lot of the time people [with mental illness] are using illegal drugs to self-medicate.”

In Coffey’s courtroom, probationers are praised, spoken to gently, and at times offered candy from a bowl at the bench.

On Silvestri’s last day in court in Lowell, Brennan was not offering candy. He had not yet decided what to do about Silvestri’s failed test — her lawyer told her Brennan was also considering sending her to an alcohol treatment center. But by then, Silvestri had seen too many probationers sent to jail for positive drug tests.

“I think they’re going to lock me up,” Silvestri told her aunt about an hour before she collapsed.

Burke, Brennan, and another judge attended Silvestri’s funeral in Wilmington. Joan Silvestri recalled being touched at first. But then, she said, she wondered whether there was more to their attendance than a simple desire to pay their respects.

“Did they have a sense of guilt?” Joan asked herself. “Did they feel like they had pushed her to the limit?”

A few weeks after the funeral, Brennan addressed Silvestri’s death in court, reading a letter from Trial Court Chief Justice Paula Carey and the head of the Lowell District Court that defended his actions.

“The death of this drug court participant,” they wrote, “is a tragedy and it is felt keenly every day by those who worked persistently and devotedly to provide the opportunities for a substance-free life.”

Six years ago, Utah hired a retired judge to visit its mental health and drug courts to make sure they were following national standards. The rigorous examination involves a 77-item checklist for mental health courts (110 for drug courts). The retired judge visits each courtroom at least once every two years to ensure compliance.

“They can’t start a new court or continue operation unless they have been certified,” said Richard Schwermer, Utah’s assistant state court administrator, who oversees the state’s specialty courts.

Ohio, another national leader in mental health courts, has been enforcing quality standards in its courtrooms for three years.

Massachusetts, by contrast, only just launched a review process for specialty courts this year, starting with drug courts.

Still, many observers agree that attitudes about mental illness in the state courts are improving.

Most judges are eager to receive more training and are receiving it, they say. Newly hired court officers now receive at least four hours of training to help them learn how to cope with defendants with mental illness. Subsequent annual trainings include 1½-hour sessions that teach skills such as how to identify mental illness and signs a defendant may try to commit suicide, according to the Trial Court.

The Trial Court is also compiling a statewide list of services and resources that probation officers and judges can access online, which could make it easier for them to help defendants with mental illness.

“We have to take people as they come to us and have them hopefully leave our system better than when they came to us,” Carey said. “I won’t say that we achieve that result 100 percent of the time, but certainly we will strive to do that.”

Still, the reforms to date are modest in the face of a crisis in which thousands of defendants with mental illness currently get no help at all. Many others have problems more serious than court officials can manage — a stint in mental health court did not prevent Bodio Hutchinson, a troubled homeless man, from stabbing two park rangers on Boston Common two years ago. In September, Hutchinson accepted an eight- to 10-year sentence for attempted murder.

Advocates for those with mental illness said such cases are a reminder that no court can replace a robust community treatment system.

But Spence, the court administrator, recognizes the role that courts play in the crisis. In May 2015, at a training session for mental health court officials in Worcester, he reminded the judges, probation officers, and lawyers how the courts can contribute to the warehousing of people with mental illness in jails and prisons, what many people call “the new asylums.”

“Is that more humane than housing them in a hospital system? I think the answer is no,” Spence told the crowd. “We must ensure that we fulfill the promise of deinstitutionalization and don’t just replicate those Victorian hospitals with prisons.”

Contact the Spotlight team

- Tipline 617-929-7483

- Email [email protected]

- Twitter @GlobeSpotlight