The desperate and the dead: community care

State mental hospitals were closed to give people with mental illness greater freedom

but it increased the risk they’d get no care at all.

“My son is dead,” the man said, distraught over the heroin overdose that took his 30-year-old child. He’d feared this might happen, and yet he couldn’t stop it. Now he needed help for himself.

It was an autumn afternoon last year. The father, a 65-year-old retired construction worker, sat in the Lowell office of Ken Powers, a counselor he’d been seeing for more than a year. The man pulled out a tribute he’d written to his son and began to sob. Powers started crying, too.

Then came a knock on the door — highly unusual in the middle of a private counseling session. It was the program director at Powers’s agency, Comprehensive Outpatient Services Inc. The for-profit behavioral health company had just filed for bankruptcy, they were told. The building was being seized. Powers had less than an hour to get out.

His counseling session cut short, the father instead helped Powers pack up his office, filling his own car with Powers’s musical instruments and books. It was an abrupt, unsettling end to a much-needed moment of connection.

“It was like a slap across the face,” said the man, who asked not to be identified.

The sudden closure of Comprehensive Outpatient Services — which left as many as 2,500 people temporarily without counseling, psychiatric prescriptions, and other critical assistance — was a sharp illustration of the destructive forces splintering the Massachusetts mental health care system.

From a father depressed about his lost son to those at risk of becoming dangerous to themselves or others, many people with a pressing need for mental health care all across the state are not getting it, left largely to navigate the dwindling treatment options on their own. Some can handle the challenge, if barely; too many simply cannot.

Nearly a third of community mental health providers in Massachusetts reported closing clinics from 2013 to 2015, according to one study, a trend that has continued this year. Two intensive day programs for adults in the Boston area with severe mental illness closed in recent months, displacing 100 more people.

The shutdowns underscored a truth that providers have long known: Mental health care is often a money loser, in large part because of the state’s long-term neglect. The state Medicaid program, MassHealth, has for years reimbursed providers at rates far below the cost of treatment, meaning they lose money on every person they serve.

“We just couldn’t sustain the loss over time,” said Nancy Gajee, a top psychologist at the nonprofit May Institute, which in March closed one of the two adult day programs, Crossroads in West Roxbury.

The daily struggle to find and pay for care is an indictment of political leadership in Massachusetts and beyond that spans generations.

Governors from Francis Sargent to Deval Patrick, House speakers, Senate presidents, and other legislative leaders, and federal officials together cut hundreds of millions of dollars in mental health spending over the last 50 years. They closed psychiatric hospitals but funneled comparatively little of the savings into community treatment programs — once successfully defying a federal court order requiring that they spend millions more. They stood by as community service providers withered and shrank, and as counseling, psychiatric prescribing, and other services grew harder to access. They allowed state oversight to erode to dangerous levels.

The result is a system that’s defined more by its gaps and gross inadequacies than by its successes — severely underfunded, largely uncoordinated, often unreliable, and, at times, startlingly unsafe. It is a system that prizes independence for people with mental illness but often ignores the accompanying risks to public safety. A system that puts blind belief in the power of antipsychotic drugs and immense trust in even the very sickest to take them willingly. A system that too often leaves people in mental health crisis with nowhere to turn.

It was never supposed to be this way. President Kennedy and his allies recognized the grim state of America’s mental institutions — which at their peak housed nearly 560,000 people — and promised a robust, humane system of community-based treatment in their place.

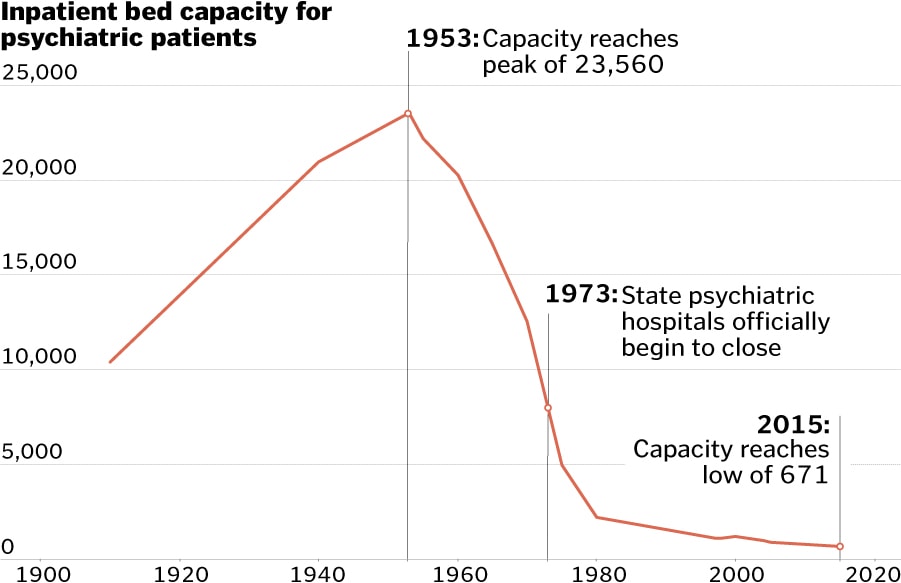

Massachusetts has reduced state-funded inpatient psychiatric beds by more than 97 percent.

Source: Massachusetts Department of Mental Health

Aditi Bhandari/Globe Staff

From Washington to Beacon Hill, the vision went like this: People afflicted by mental illness would receive care out in the world, instead of being locked away in dreary fortresses. They would live with family or in group homes and retain sovereignty over their lives and treatment. They would receive support and monitoring from a tight-knit network of mental health clinics, doctors, and hospitals.

“Reliance on the cold mercy of custodial isolation will be supplanted by the open warmth of community concern and capability,” Kennedy assured Congress, just months before his assassination in 1963.

Massachusetts political leaders showed flashes of good intentions, too. Sargent championed community care and moved to modernize archaic mental health laws in the 1970s. Michael Dukakis, haunted by the horrid conditions he’d witnessed while visiting institutionalized children, in 1978 accepted a federal consent decree establishing extensive community treatment options in Western Massachusetts. In the 1990s, Governor William Weld and Charlie Baker, then Weld’s top health and budget aide, turned mental health treatment over to private companies and nonprofits, promising “equal or superior” care to what state-run facilities provided.

The savings to the state were very real; the promise of “equal or superior” care too often a mirage.

That calculus continued a long-running pattern. For over 60 years, as state leaders cut the mental hospital population from more than 23,000 to less than 700, they, along with federal leaders, walked away from their promised investments in community treatment.

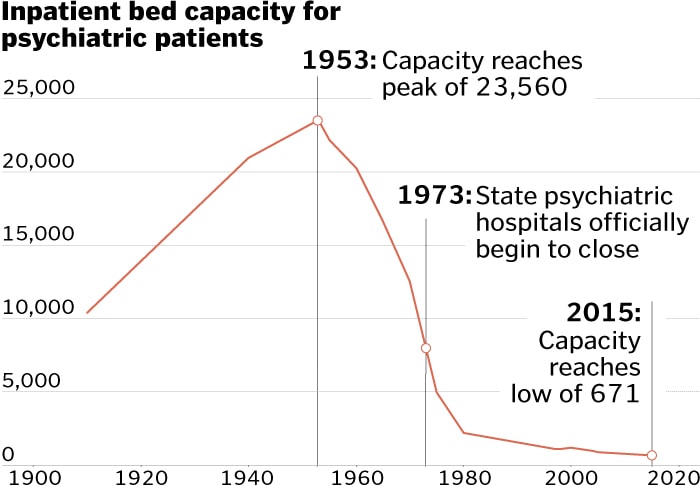

The state Department of Mental Health slashed spending on inpatient care by more than half over 20 years, while the agency’s spending on outpatient treatment barely increased.

Source: Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, US Census

Aditi Bhandari/Globe Staff

Massachusetts slashed spending on inpatient mental health care by more than half — or nearly $161 million — from 1994 to 2013, including inflation. But a Spotlight analysis shows that over the same period, per-capita spending on outpatient care by the state Department of Mental Health barely budged. State budget-writers instead put new funds into areas like public schools and transportation.

“The state did not want to put the kind of money in that needed to be done to make a viable system,” said Barbara Rhuda, a leader of the Massachusetts chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness in the 1990s. “I think it’s come back to kick them all in the you-know-what.”

As the Department of Mental Health spent less, the agency ceded control over what had once been a state-run system, replaced by a profusion of private providers making separate decisions on how to administer care. Even though MassHealth now commits more than $1 billion annually to mental health and substance abuse treatment, the system has grown so diffuse that finding help is increasingly complicated and capricious.

Today, state Senate President Stanley Rosenberg said it would likely take the kind of court order that has often driven social policy in Massachusetts to force legislators to make major additional investments in adult mental health care. Only following a class-action lawsuit known as Rosie D., after the lead plaintiff, did the Legislature boost behavioral health funding for thousands of children on Medicaid by more than $200 million annually.

“For the most part, we’re still pushed into whatever it is we do,” said Rosenberg, an Amherst Democrat. “It’s not because we don’t care. It’s because there are so many compelling, competing interests chasing very few new dollars.”

At the federal level, President Reagan in 1981 effectively ended Kennedy’s ambitious plan to build federally funded community mental health centers across the nation. Only 789 of the originally imagined 2,000 centers were built. About two dozen were established in Massachusetts, fewer than half the number federal mental health officials had vowed.

Most people paying the price for this patchwork system suffer privately, their trials unfolding out of sight. Sometimes, though, the consequences of lackluster care, or the absence of care altogether, turn tragic. These cases reveal, in sudden, horrifying fashion, the gaps in safety nets that were stretched thin over the years before finally giving way.

Martha Tipper packed the swimming gear, put her children in the stroller, and started toward her car at the Whole Foods in downtown Boston. After 90 sweltering minutes at the Charles River Park pool, it was time to go.

Walking along Thoreau Path that afternoon in July 2012, Tipper called her husband to ask about buying salmon for dinner. A woman with a floral shirt and large headphones suddenly appeared at her side.

Her name was Diane Huggins. Nothing in her manner hinted at the burden she carried inside.

A 58-year-old grandmother, Huggins had spiraled into darkness, consumed by the psychosis she had battled for more than three decades. On her medication, she could manage pretty well; but off it now, again, she posed a known risk to others. And yet no one had stepped in.

Not the outpatient psychiatric practice she’d relied on at Boston Medical Center, which raised no alarms after she stopped showing up for treatment. Not her former psychiatrist, who’d taken a job at another hospital. Not the state Department of Mental Health, which had monitored her for years before concluding she was fit to manage her life.

“What time is it exactly?” Huggins asked Tipper.

“2:04,” Tipper said.

With that, Huggins drew a butcher knife from her purse and brought it down toward Tipper’s almost 2-year-old son, narrowly missing him. Tipper threw the stroller over, her son and 4-year-old daughter still inside, as Huggins continued to slash, cutting Tipper’s hand, arm, and calf.

Charles Sadowski, a retired English teacher walking nearby, knocked Huggins down. Tipper grabbed the children and fled. Aided by others, Sadowski wrestled the knife away and subdued Huggins until police arrived.

“OK, the cops are here,” Huggins said. “You can get off of me.”

Those words — spare, almost matter of fact — spoke to her history. In separate attacks years earlier, Huggins had stabbed two other perfect strangers to quiet the inner voices. Here she was in police custody again.

Huggins had actually received far more mental health treatment than most, but the level of care was uneven and, by any measure, insufficient. Every time the system broke down, leaving her mental health largely in her own hands, she became a danger to society. Huggins — and the public — required what the system could not provide: close monitoring and uninterrupted treatment throughout her life.

Her case is exceptional — only a small fraction of those suffering from a mental illness are prone to violence — but hardly unique. From 2005 through 2015, more than 10 percent of homicides with known suspects were committed by people with a history of mental illness or who had clear symptoms, according to a Spotlight Team analysis. Huggins’s pattern of attacks underscores a larger question at the core of this Globe investigation: If the care system can’t meet the needs of someone in such extreme and obvious straits, who is it there for?

The risk of violence from a small group of severely ill people — often untreated — was laid bare after Pericles Clergeau, a young man with multiple psychotic conditions, was released from Westborough State Hospital as it was closing in 2010 to help address a state budget gap.

Clergeau’s record of psychiatric treatment and hospitalizations dates back to preadolescence and fills some 7,000 pages, according to his lawyer and court records. But despite previous violent assaults on fellow patients, school staff, and mental health workers, he was set free to navigate the world on his own.

Less than a year after leaving Westborough, Clergeau landed at the Lowell Transitional Living Center, where, on the morning of Jan. 29, 2011, he confronted Jose Roldan, a 34-year-old shelter employee who’d tried to help him. In a fit of paranoid rage, Clergeau, then 18, pulled a knife and stabbed Roldan to death.

Roldan’s murder came in a string of fatal attacks on vulnerable employees of shelters or mental health facilities.

Just nine days earlier, Deshawn James Chappell, a 27-year-old with a record of aggression who was off his schizophrenia medication, stabbed 25-year-old counselor Stephanie Moulton in the neck at a Revere group home. He dumped her body behind a church in Lynn.

Then on March 24, Nicholas Davenport, a 20-year-old with a history of mental illness, according to court records, allegedly attacked Jason Lew, a staff member at the Pocasset Mental Health Center, as Lew tried to restrain him. Lew, 60, died two weeks later from what prosecutors say was a related heart attack. In 2012, a judge ruled Davenport incompetent to stand trial for manslaughter.

The risks posed by the state’s inadequate community care system, especially in dealing with the most severe cases, should have, by that point, been abundantly clear. Less than two years earlier, in 2009, a state panel had identified an alarming pattern of people with severe mental illness returning to hospital psychiatric units soon after leaving. That suggested they weren’t getting better or couldn’t readily handle life on their own. It was, the panel noted, “a clear warning sign that the public mental health system is in trouble.”

After Moulton’s murder, a Department of Mental Health task force warned that after years of budget cuts, the mental health care system lacked the beds, clinicians, services, and communication among its many different players to meet the increasing demands posed by people with serious mental illness.

“If we care about safety, we cannot pretend that all is well,” wrote the task force cochairmen, Kenneth L. Appelbaum, a psychiatry professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, and retired judge Paul F. Healy Jr.

Yet, the public warning did little to mobilize efforts to stop the violence. From the release of that 2011 report through the end of 2015, another 51 people were killed by assailants with a diagnosed mental illness or strong indications of it, the Spotlight analysis found. Over the same period, 32 people with signs of mental illness were shot by police, 17 of them fatally.

While state leaders took some steps to patch the failing system, such as boosting spending, in other ways they continued to weaken it. They rebuffed a plea from Moulton’s family to equip group home workers with panic buttons to summon help, and Governor Deval Patrick reduced services at Taunton State Hospital and targeted it for closure.

Massachusetts once led the nation in ensuring that people suffering from severe mental illness were cared for. Indeed, the driving force behind the country’s first psychiatric institutions, in the 1800s, was a Massachusetts reformer named Dorothea Dix, who’d been appalled at seeing people with mental disorders confined to unheated jail cells.

Out of her activism grew institutions built on high ideals, if also little scientific understanding of mental illness. Westborough State Hospital, for one, opened on the shores of Lake Chauncy in the 1880s with the aim of providing sunlight, fresh air, and tranquility. Patients worked a farm that produced milk, pork, and a bounty of fruits and vegetables. Jimmy Piersall, a star outfielder for the Red Sox, was stabilized there after a breakdown during the 1952 season, a recovery made famous in the movie “Fear Strikes Out,” based on his own book.

The erosion of Massachusetts’ early leadership has been a long time in the making, coming as its institutionalized population dropped from one of the largest in the nation to among the smallest on a per-capita basis.

Massachusetts now ranks near the bottom of states in keeping people with mental illness out of prison, in the use of dedicated courts for people with mental illness, and in training police to handle mental health crises, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center, a nonprofit reform group based in Virginia. And Massachusetts is one of only a handful of states that still maintains separate agencies for mental health and substance abuse, despite a clear national consensus that they should be treated together, because so many people with mental illness also struggle with drugs or alcohol.

And a 2013 study showed that the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health spent less money per capita than the national average even though the cost of living here is among the highest in the country. In New England, only Rhode Island spent less.

None of the last three governors nor William Weld, who presided over key changes to mental health care in the 1990s, agreed to an interview about the system’s unraveling. But each had a hand in it.

With Charlie Baker as his point man, Weld shut down at least five inpatient mental health facilities, eliminating some 900 beds, and reduced Department of Mental Health staff by 40 percent over five years. Weld boosted spending on community care, but he and Baker also triggered a seismic shift: They began farming out state services to private vendors, such as the for-profit Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership, which in 1996 began managing mental health care for people on MassHealth.

The shift to private providers meant the federal government, through MassHealth, paid a larger share of Massachusetts’ mental health bills. But the move to a privately operated system also led to patients being denied treatment, sent home from hospitals too soon, or left to fend for themselves on the streets.

A leaked 1995 memo from the Department of Mental Health reported a 79 percent surge in annual deaths of people in the state mental health system from 1990 to 1994 as well as alarming increases in suicides, injuries, and patients walking away from mental health care facilities. One psychiatrist at the time called privatization “a social catastrophe.”

Meanwhile, the state’s role overseeing mental health care shrunk steadily, and work once done by state employees, such as tracking down patients who missed appointments, was increasingly left undone. Today, the Department of Mental Health directly serves less than 10 percent of the estimated 238,000 Massachusetts adults who struggle with serious mental illness — a much smaller share than the agency once managed.

The result, the Legislature’s Mental Health Advisory Committee concluded in 2014, is a system in which accountability for the care of the most severely ill people is often “lost or nonexistent.” They bounce from hospital to hospital, caregiver to caregiver, until, with some frequency, something awful happens.

Still, governors have continued closing psychiatric hospitals. Under Mitt Romney, the state shut down Medfield State Hospital in 2003, and, crucially, shuttered a specialized unit at Taunton State Hospital for men with severe mental illness who were prone to violence but not necessarily criminals. State officials contended the so-called Difficult to Manage Unit was no longer needed, having identified “safer, less traumatizing, and more clinically appropriate ways to manage patients.” But its closure also shaved another $2.2 million from the state budget.

The shutdown deprived the state of a vital facility for a small population of severely ill men who could be dangerous to others and required intensive, secure care, said Bruce Swartz, a psychologist who helped design the unit and served as its clinical director for eight years. That would include people like Pericles Clergeau, who Swartz said would have been a candidate for the unit had it still existed in 2010 when Clergeau was a patient at Westborough State Hospital.

“It was extremely distressing to see the Commonwealth terminate a service that served such an important function, was well utilized, and enjoyed a statewide reputation for excellence,” Swartz said.

A few years later, the Patrick administration shut Westborough State Hospital earlier than expected to erase a $13 million hole in the Department of Mental Health budget.

“The place was going to close, and that was that,” said Kathleen Torrey, who was a nursing supervisor at Westborough. “The people had to be out.”

Baker so far has signed two state budgets that boost mental health spending by 4 percent over two years and make more significant investments in combating substance abuse. That has allowed some improvements, though not nearly enough to fix the glaring deficiencies in the system that have accumulated over decades.

And it’s unclear how far the Legislature is prepared to go in supporting mental health care reform and expansion. House Speaker Robert DeLeo declined to be interviewed, but one of his top deputies said the lingering stigma around mental illness makes it difficult to build support for major funding increases.

“No matter how you slice it, we just don’t have enough,” said state Representative Patricia Haddad, a Somerset Democrat who cochaired the Mental Health Advisory Committee. “We wouldn’t even be having this conversation if it were broken limbs or hearts.”

If you go to sleep, Diane Huggins told her children, I will kill you.

Some nights she threatened to kill all three. Other nights the threats were more specific.

Her daughter, Arianne Neves, was only 6. But she knew a mother wasn’t supposed to say these things. She’d stay up all night to keep watch over her younger brothers.

The voices in Huggins’s head in those days, in the early 1980s, were ferocious and unrelenting. They blamed her for the death of a boyfriend’s child, she would later tell a state psychologist. They called her a dog and commanded her to murder.

Desperate to quiet the refrain, Huggins forced her children to scour their Dorchester apartment. “Like if we scrubbed the walls the voices would go away,” Neves said.

But they only grew louder. On the afternoon of July 11, 1985, two months after the state Department of Social Services had taken Huggins’s children away, the voices delivered a command she could not refuse.

“If you want us to leave, you’ll have to kill someone else,” the voices said, according to a psychologist’s report in her court record.

Huggins, then 31, grabbed a knife, burst outside to Seaver Street, and attacked a 4-year-old boy playing tag with his older brother. Huggins pushed him down and stabbed him repeatedly.

“Are you satisfied now?” she shouted afterward, later turning herself in to police.

A neighbor ran out and pressed towels to the boy’s wounds. Taken to Boston City Hospital, the boy survived. Once the shock wore off, the pain hit him hard. He was mute for weeks.

This stabbing and subsequent arrest, which took place decades before the 2012 attack along Thoreau Path, set Huggins on a long, rocky journey of recovery and relapse. She would enjoy productive stretches but never fully shake her murderous delusions.

Found not guilty by reason of insanity, she spent almost nine months at Metropolitan State Hospital in Waltham, a state psychiatric facility that would close a few years later. Doctors thought she suffered from either schizoaffective disorder or depression with psychotic features. She would be diagnosed with both in later years.

In an earlier era, a woman like Diane Huggins could well have spent her life confined to an institution. Instead she entered adulthood just as advocates, policy makers, and civil rights lawyers were winning greater autonomy for people with mental illness. Those changes, which played a massive role in emptying the squalid mental hospitals, gave Huggins multiple chances to live independently.

Huggins was released from Metropolitan State in April 1986 after showing steady progress and complying with treatment. She eventually moved to a Dorchester facility for homeless women and tried to rebuild her life. It largely worked for seven years, although she did assault a fellow resident in 1992 in response to what she believed was a racial slur.

Then in April 1993, Huggins, who made regular visits to an outpatient clinic but otherwise had no apparent oversight, stopped taking lithium after a severe outburst of acne and cysts, a relatively common side effect. She spiraled into paranoia. She isolated herself in her Charlestown home and canceled appointments, artfully masking her descent from doctors and family.

On the afternoon of May 25, Huggins got hungry and went to a nearby Foodmaster, bringing a knife for protection, she later told a psychiatrist. She encountered a stranger, Tracy Luisi, in a grocery aisle, who she believed was making derogatory comments.

Huggins pulled out the knife and stabbed Luisi 11 times as Luisi shielded her 4-year-old daughter. Luisi survived but lost sight in her eye, according to court records.

Again found not guilty by reason of insanity, Huggins was sent to Taunton State Hospital, where, despite two potentially fatal knife attacks on her record, she was regularly assessed for signs of progress that would allow her to reenter society.

In 1997, four years after the assault on Luisi, with Huggins again living independently, the state Department of Mental Health received a judge’s permission to assign a guardian to monitor her treatment. Under the so-called Rogers order, she was required to receive regular injections of Haldol, an antipsychotic, and to be seen regularly by her guardian, psychiatrist, and state case manager.

“With treatment,” the court papers say, “it is hoped that she will be able to live safely and productively outside the hospital setting without being a danger to herself or others.”

Sal Giarratani has never shaken the memory.

It was the late 1950s. He was a young boy, riding in the backseat of his aunt’s car, peering out the windows as they passed by Boston State Hospital in Mattapan.

“All of these people clinging to the fences, looking at the traffic,” said Giarratani, who would later spend 41 years as a mental health worker and police officer with the Department of Mental Health.

Originally built on hope and compassion, many psychiatric institutions became, over the first half of the 20th century, wretched warehouses. Photographs and news accounts of naked, forlorn, and utterly forgotten patients shocked the public conscience, even in once-pioneering Massachusetts, where stately, Victorian-era state hospital campuses hid a dark truth.

Abuses at what is now Bridgewater State Hospital — men without clothes led into barren cells; guards baiting and teasing patients — were exposed in Frederick Wiseman’s 1967 documentary “Titicut Follies.” Such abuses only affirmed a growing belief that voluntary, community-based treatment was simply the right thing to do, even if it meant some severely ill adults might reject all medication and help.

Civil rights activists and disability rights lawyers around the country made it their mission to end the harsh restrictions imposed on people with mental illness — to give them choice and restore their humanity. These lawyers and activists often found a willing ear in the courtroom, where sympathetic judges repeatedly expanded patient rights and forced states to establish proper systems of care in the community.

In Massachusetts, a 1978 Supreme Judicial Court decision made it far more difficult to involuntarily commit someone to a psychiatric hospital. After the case of Laura Hagberg, an elderly woman seeking release from Worcester State Hospital, anyone seeking to confine a person with mental illness would have to prove “beyond a reasonable doubt” that the person was a danger to themselves or others.

The same year, US District Judge Frank Freedman approved a consent agreement compelling the state to establish alternative treatment options for those confined unnecessarily to Northampton State Hospital.

“Residents and clients are entitled to live in the least restrictive, most normal residential alternative,” read the landmark agreement, which resolved a class-action lawsuit brought on behalf of patients.

The decree called for Northampton’s patient population to drop from about 370 to 50 within three years. The exodus in fact took far longer — in part because the administration of Governor Ed King in 1981 successfully challenged the spending levels ordered by the federal judge — but many credited judicial intervention with bringing a comparatively effective community care system to Western Massachusetts.

Subsequent rulings by the state’s highest court established the right of people with mental illness to refuse psychotropic drugs like Thorazine, whose power to blunt psychotic behavior had made deinstitutionalization possible when it came into use in the 1950s.

Massachusetts — with its culture of civil rights activism, vocal community of people in recovery from mental illness, and influential voices such as Marylou Sudders, the state secretary of health and human services — has gone further than most in safeguarding the right to decline mental health care.

Unlike nearly every other state, Massachusetts has refused to adopt a so-called assisted outpatient treatment law allowing court-ordered treatment for people with severe mental illness. Opponents fear it would be misused, forcing treatment on people whose behavior is merely disruptive or inconvenient, not dangerous.

The civil rights imperative also provided convenient cover for leaders in Massachusetts and elsewhere who were shutting down mental health facilities mostly as a way to save money.

“Cynical governors saw that as an opportunity to close facilities, dump people out . . . and save the state tons of money and not provide them with services,” said Bob Fleischner, a longtime disability rights attorney with the Center for Public Representation in Northampton.

Under Deval Patrick, once a leading civil rights lawyer himself, Massachusetts accelerated the closure of Westborough State over 10 months in 2009 and 2010. It was a money-saving move but it squared, too, with a 1999 US Supreme Court ruling that the disabled must be served “in the most integrated setting” possible.

Many Westborough alumni fared well after being released into the community, according to state surveys of selected patients. Joel Skolnick, who was Westborough’s chief operating officer, recalled one man who’d been anxious about leaving, but called to tell Skolnick afterward about the thrill of liberty.

“I’m sitting on the porch looking at the street, and I’ve never had this much freedom in my life,” the man said, according to Skolnick.

Other former patients were hospitalized repeatedly or returned to state institutions. A few went to jail. Pericles Clergeau wound up on the streets, eventually landing at the Lowell Transitional Living Center where he thrust a knife into Jose Roldan’s neck, killing him.

When Clergeau pleaded guilty on May 31 to second-degree murder, his lawyer, Keith Halpern, stood up in Middlesex Superior Court and said Roldan’s death could have been prevented had the mental health care system not failed Clergeau so badly.

“There are thousands of people like this who need to be helped,” Halpern said. “And we’re not giving them the help.”

The chronic underfunding of mental health treatment is a big reason why. MassHealth, a major funder of mental health care services in this state, has long forced providers into an unsustainable position, according to interviews with mental health practitioners and a 2013 report commissioned by the Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership. The state insurance program paid less than two-thirds of the cost of providing diagnostic services, the study found, and barely more than half of the cost of providing group therapy.

The closure of Comprehensive Outpatient Services, which was first detailed in the Lowell Sun, wasn’t solely a function of poor state reimbursement — a judge in the bankruptcy case cited the owner’s financial incompetence. But the shutdown underscored how tenuous the mental health care system had become.

“It hurt a lot of people,” said Ken Powers, who, in his new job with Bridgewell, a growing nonprofit serving Eastern Massachusetts, resumed counseling the man who’d lost his son to heroin.

Under Baker, the state has pumped an additional $41 million into MassHealth reimbursement rates, which providers say is a promising start toward rebuilding critical mental health services.

But the underfunding of mental health care also affects people who rely on private insurers for their treatment. One in six mental health clinicians in private practice say they no longer even accept insurance because repayment rates are so low, according to a 2015 study by CliniciansUNITED, a union-affiliated group. That means people who want such services have to pay out-of-pocket. Nearly half of clinicians surveyed by CliniciansUNITED said insurance pressures caused them to turn away five or more potential patients each month.

One Brookline social worker said she stopped accepting United Behavioral Health insurance because its payment rates were so low that her take-home pay came to well under $35 an hour.

“Rates have remained flat. My cost of living has gone up significantly,” said the social worker, who asked that her name not be used. “It’s embarrassing how poorly we get paid.”

Insurers reject assertions that they underpay mental health care providers, though Lora Pellegrini, president and CEO of the Massachusetts Association of Health Plans, said they are open to a dialogue about rates. “I think we pay providers adequately,” she said.

And pockets of promise do exist within the beleaguered system. Mobile crisis teams, which respond to psychiatric emergencies in schools, hospitals, and homes, handled more than 100,000 calls in fiscal year 2014, a 26 percent increase from five years earlier. Massachusetts in 2015 also won a nearly $1 million grant from a new federal pilot program that aims to establish, if further funding emerges, community clinics nationwide — much like the ones Kennedy pushed a half-century ago.

But these efforts to date are like fingers in the dike. Gaping holes remain — holes that mental health workers, family members, and advocates for people with mental illness have warned about for many years.

It’s an inescapable legacy of deinstitutionalization, as it was managed here: Although many former patients went on to better lives, severely ill people were pushed into a community system that they weren’t ready for — and that wasn’t ready for them. What has followed is a revolving door of emergency room visits, frequent run-ins with police, and nagging fears among family and providers that someone under their care will turn violent.

No one is calling for a return to the old institutions and old ways, but the status quo is untenable.

“First and foremost it’s inhumane,” said Jim Durkin, director of legislation, political action, and communications for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, which has fought service reductions. “It’s also a colossal waste of money.”

Diane Huggins was thriving. Her state-supervised treatment was working — so well, in fact, that the Department of Mental Health concluded in January 2004 that Huggins was “now competent to make her own decisions.”

The state asked Probate Judge John Smoot to dismiss the Rogers guardianship, despite Huggins having twice been found not guilty by reason of insanity for violent crimes. Smoot granted the motion.

At first, Huggins voluntarily continued with the Haldol injections. She cultivated a therapeutic relationship with Peggy Johnson, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center. She earned a degree from Bunker Hill Community College, got an apartment in the West End, and even assumed the role of loving grandmother and baby sitter to the children of her daughter, Arianne Neves.

But in quick succession in 2009, Huggins was rocked by the deaths of her husband — they had separated but remained close — and her youngest son, who died at 31 from kidney failure. Then Johnson left Boston Medical Center at the end of 2011 to become chief of psychiatry at Carney Hospital.

Huggins at the time reported symptoms of depression and psychosis, but Johnson felt that she was reasonably stable, especially measured against Johnson’s other clients. Accordingly, when making arrangements to leave the practice, Johnson did not flag Huggins as a “high risk” patient.

But soon after, Huggins dropped out of treatment and stopped taking her medication, concealing her decline once again.

Her primary care physician, Richard Pels at Cambridge Health Alliance, grew concerned about her behavior early in July 2012. He asked his nurse to track her down. But when Huggins responded curtly on the phone, “I’m fine,” Pels saw no grounds to pry further, he said in an interview.

Pels said his office had sought Huggins’s Boston Medical Center records in 2009 but never received them — a somewhat common occurrence in the siloed health care system, he said. Thus Pels had limited knowledge of her psychiatric care and medication history. He knew nothing of her past violent attacks, he said.

On July 17, 2012, about a week after that phone call from the nurse, Huggins’s delusions crescendoed again. Around 2 p.m. that day, Huggins lunged for Martha Tipper’s children.

Neves was devastated when she got word. So was Peggy Johnson when she learned of the attack much later.

“I felt all of those complicated emotions,” Johnson said. “Failure in terms of just, can we do better? Is there a way that people can be cared for, allowed to be contributing members of society until they’re not? And then have some capacity to respond to that?”

Pels added, “I think the larger ‘we’ failed her.”

Neves, who said she is her mother’s legal health care agent, was angry that no one from Boston Medical Center alerted her that her mother had dropped out of treatment.

“Nobody said anything to anybody,” Neves said.

Boston Medical Center declined to address Huggins’s case specifically, saying in a statement: “Caregivers must work within the rules and structure of the current system, including strict patient privacy laws designed to protect civil liberties, in their quest to provide the best care possible for patients.”

Huggins, despite years of work, often successful, to check her violent impulses, had now gone after random children or families with a knife three times. For the third time, she was found not guilty by reason of insanity, a rarity in a criminal justice system that typically treats mental-health defenses with deep skepticism.

A psychiatrist who evaluated her after the 2012 attack wrote of her mental health treatment, “No crisis management plan was reportedly in place.” The passivity of those words was fitting. There had been no emergency plan, no one to step in when things began to slip. Any crises were Huggins’s to manage on her own.

Last summer, Huggins was discharged from Lemuel Shattuck Hospital in Jamaica Plain, where she was held after the 2012 attack. Over the objection of Suffolk County prosecutors, she was moved to a nursing home west of Boston.

Now 62, Huggins uses a wheelchair to get around. She has difficulty tying her shoes or showering without assistance, Neves said.

The nursing home is a locked facility, her daughter said, but Huggins enjoys some freedoms. Neves takes her to Walmart and brings her home for holidays. A friend takes her to Dunkin’ Donuts. Huggins, who declined to be interviewed, receives a regular Haldol injection, said Neves, who accompanies her to medical appointments.

“I feel like she’s at a point where she can live what’s left of her life . . . and not be a danger to herself or anyone else,” she said.

The boy Huggins stabbed in 1985 has since graduated from Boston College High School, earned a political science degree from Boston College, and worked in banking. He now works for the state helping families in need.

He still bears the knife scars but has sympathy for Huggins.

“I hope she gets what she needs,” said the man, who is now in his 30s and asked not to be named. “I don’t want another kid to go through what I went through.”

Neves understands the pain Huggins has caused. Neves has known her own: the burden of living, for all these years, with the weight of her mother’s illness.

“The family,” she said, “was a victim, too.”

Contact the Spotlight team

- Tipline 617-929-7483

- Email [email protected]

- Twitter @GlobeSpotlight