Tom Brady: Ageless wonder

Number 12 at 39 is something of a biological miracle

By Mark Arsenault and Andrew Joseph

om Brady did not defy age this season, he knocked it down and left cleat marks.

The quarterback’s age-39 season was statistically among the best of his 17-year career with the New England Patriots. His 2016 passer rating, a complicated mash-up of metrics the NFL uses to measure quarterbacks, is tied for 10th best all-time in a season, at 112.2. He bettered that rating only once in his career, in 2007, when the Patriots became the first NFL team to win all 16 regular season games.

What’s maybe most remarkable about his 2016 performance is that it came at an age by which many other luminaries of the position — Dan Marino, Joe Montana, and John Elway, to name three — had already retired.

Sign up for Point After, the Globe’s NFL newsletter

“Aging is associated with an inevitable and inescapable physiological decline,” says Wojtek Chodzko-Zajko, a kinesiology professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who is just full of bad news. “No one has ever escaped from that physiological decline — the only way to escape it is to die.”

It can’t be escaped, but it can be put off a while.

Beyond maniacal workouts to maintain his VO2 max (the amount of oxygen an athlete can use under all-out exertion), the right DNA and a good dose of good luck, there is likely a combination of factors that have contributed to Brady’ successful late career. “It doesn’t mean that he’s not aging,” said Chodzko-Zajko. “It means he’s utilizing some of the strengths that happen with increased experience and increased wisdom to compensate for some of the physical changes that occur.”

Here we break down, body part by body part, what science suggests the average 39 year-old human encounters, and just how Brady might be defying those expectations. Keep reading below that for how NFL rule changes have advantaged Brady plus what some previous greats of the game — Warren Moon, Steve Grogan among others — say about his longevity and just how long he could play.

Brain

Brady has brushed off questions about how many concussions he has suffered, but the answer appears to be comparatively few, if any, downplaying the chance he suffers from the headaches or mental fogginess — or concern about his long-term neurological health — that has pushed other players into retirement.

Another advantage behind Brady's lasting success? He has played for one team and one coach for so long. Quarterbacks need a few years to learn and execute their teams' offensive strategies. By staying put, Brady has been able to hone his mastery and maximize it rather than starting fresh with a new team every few years.

Eyes

Vision can start to diminish around age 30, but that’s more likely to affect a baseball slugger trying to read the seams on a curveball than a quarterback looking downfield. And if athletes stay physically healthy, it is only natural that they'd improve in certain aspects of the game late in their careers thanks to experience, whether it be in reading defenses, anticipating receivers' cuts or knowing where a blitz is coming from — so-called perceptual skills. “The more, essentially, flash cards of plays they’ve done, the more perceptual expertise they have,” said David Epstein, a journalist and author of “The Sports Gene.”

These skills are built up subconsciously, but experience could even help explain why Brady appears to faster on his feet as he ages. His reflexes may not be sharper — although improvements in his fitness could help his speed overall — but he now has a better sense of how a lineman will try to sack him and how to avoid that.

Heart

Exercise experts talk about V02 max, which is a measure of how much oxygen the muscles can get and use. V02 max falls as people age, in part because the heart rate slows. That means there is less blood flowing through the body, and thus less fresh oxygen for the muscles to take up. But some athletes, it turns out, can maintain their V02 max longer because their training strengthens their heart muscles. Even if it beats less often, the heart is able to pump more blood — and more oxygen — with each single beat.

What’s more, football is a sport with lots of breaks baked in, giving players a chance to recover. A throwing quarterback like Brady can probably keep playing well even if he loses some cardiovascular endurance.

Arms

Brady’s quarterback rating this year is second only to his 2007 season, when he threw 50 touchdowns. In other words, he can still throw the ball just fine. Muscle mass, however, does start to wane when people are in their 30s. With a regimen like the one Brady sticks to — with resistance training and flexibility exercises — that loss can be staved off or at least slowed, according to Barbara Bushman, a professor of exercise physiology at Missouri State University.

“If we do strength training, strength is able to be maintained,” Bushman said. “We have to use our muscles, we have to stress them, if we want to function well.” Plus, fast-twitch muscle fibers tend to get weaker earlier than other muscles, and those are not has important for Brady’s throwing arm as they are for a running back who needs explosive power to dodge defenders.

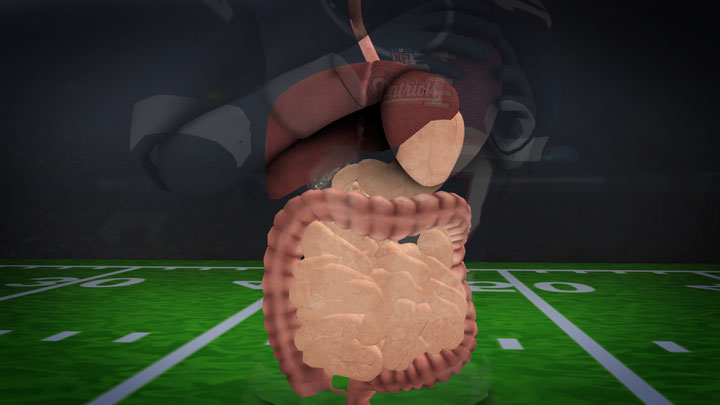

Gut

Brady’s food and beverage habits are not always backed by science — no, that sports drink won’t help you avoid a concussion — but the fact is, he eats a very nutritious diet that helps maintain his overall health.

One challenge for Brady — and anyone in their 30s: While muscle mass and bone density can be maintained with the right training, it’s harder to keep off the body fat that begins to build up around then, experts say. Starting around that age, people will naturally see about a 2 percent increase in their body fat each decade, Bushman said.

Legs

Brady has never relied on his legs as an offensive threat — which may be one reason behind his impressive stats today. His style of play (i.e. largely staying in one place) could circumvent some of affects from the muscle-mass loss, bone density, and cardiovascular endurance slowing down peers his age. Those natural processes are further decelerated by his rigorous training regime, which also lowers his risk of injury.

Brady ran an infamously slow 40-yard dash at the 2000 scouting combine, but chances are any speed he’s picked up since then has come from training and overall fitness, not some genetic factor that increased his speed as he aged. And that torn ACL that forced Brady to miss nearly all of the 2008 season? There’s been little sign of it since his return.

DNA

No, we haven’t sequenced Brady’s genome. Yet even if we had, we probably couldn’t tell you much.

Brady’s DNA does enable him to be bigger and faster and stronger than many of us. It may even help explain his dedication and ability to excel under extreme pressure. But it’s not one or even a few dozen specific genes that help him with that. Instead, hundreds, if not thousands, of genes — and how those genes are turned on and off — determine features like body composition, according to Stephen Roth, a kinesiology professor at the University of Maryland. Simply put, Brady likely doesn’t have a superhuman mutation tucked into his genetic code.

Researchers are still in the early phases of studying the connection between genetics and athletics. So far, they have found few strong associations between single gene variants and performance. A variant of the ACTN3 gene codes for a protein without which someone will have a very hard time becoming an Olympic sprinter. But even if many elite athletes have that variant, so will plenty of people whose idea of athletic achievement is bringing in all the groceries from the car in one trip. In other words, the variant is helpful — perhaps necessary — to become a top sprinter but is by no means a guarantee. (Plus, the protein helps the fast-twitch muscles contract, so someone without it could in theory become a top quarterback who, like Brady, does not rely on outrunning defenses.)

Some scientists are focused on studying the connection between genes and injury risk, while others think that perhaps the intense training elite athletes go through can kick dormant genes into high gear. “Certain types of training seem to activate genes that everyone has that will change muscular structure, even blood vessels,” said K. Anders Ericsson, a psychology professor at Florida State University. “There’s even compelling evidence that the heart will adapt to these kind of training conditions.”

It’s also possible that Brady’s genetics could explain in part why he has been able to play nearly into his fifth decade. Just as a healthy lifestyle can keep one’s “fitness age” below biological age, some experts believe people have internal aging clocks that tick away at different speeds. “We’re just beginning to understand the aging clock, but there are people who have clocks that go slower,” said Stuart Kim, a professor emeritus of developmental biology at Stanford who researches genetics and sports.

arren Moon, another Methuselah of the NFL, was selected to the 1997 NFL Pro Bowl at age 41, after a season in which he threw 25 touchdowns for the Seattle Seahawks. By age 39, he said, his athleticism had clearly declined. “I wasn’t the same runner or scrambler,” Moon, now 60, said in a phone interview. “But I made up for that with anticipation… with knowledge and command of what I was doing. Having seen everything defensively that you can see, it makes the game a lot slower, which makes you a little bit faster. Not physically faster. Your mind reacts faster.”

That seemed the case this season for Brady, who threw 28 touchdowns and just two interceptions in 12 games. (He missed four games due to a suspension, either for probably being aware of an alleged effort by team assistants two years ago to reduce the air pressure in footballs, or because the league hierarchy does not understand the Ideal Gas Law.)

NFL rules changes designed to protect quarterbacks may also be contributing to Brady’s longevity. By the mid-1990s, team officials realized that the quarterback, “the key member of the team and often the most highly paid player,” was also “the most vulnerable player on field,” said Mike Pereira, a former NFL director of officiating, now an analyst for Fox Sports. New rules sought to reduce particularly dangerous blows to the quarterback’s head and knees.

Former Patriots QB Steve Grogan, who played from 1975 to 1990, says a tweak to the intentional grounding rule was good for the health of quarterbacks, in the era after he played. A 1993 rule change gave passers running for their lives more leeway to legally throw the ball away to avoid being sacked. “When I was playing you had to have [the pass] in the vicinity of somebody, and sometimes there was nobody there to be in the vicinity,” said Grogan, now 63, in a phone interview. “So you got knocked on your can.”

Grogan played until age 37, but did not start more than six games in any year after his age-30 season. His medical record reads like a Stephen King novel: five knee surgeries; screws in his leg after the tip of his fibula snapped; a cracked fibula that snapped in practice; two ruptured disks in his neck; a broken left hand; two separated shoulders on each side; a detached tendon in his throwing elbow; and three concussions, according to a partial list of the former quarterback’s football injuries tabulated by the Globe in 2003.

“In my case I could still throw it into my mid-40s,” Grogan said. “But my knees wouldn’t let me be out there doing what I needed to do. Mobility broke down. In Tom’s case, he’s stayed fairly healthy. Still has an arm… It depends on how you take care of yourself, how you eat, how you work out, and some people — just like in life — have a longer longevity than others.”

Brady has mostly avoided serious injuries, beyond a 2008 ACL tear that cost him 15 games and inspired an NFL rule change to forbid defenders knocked to the ground from lunging into the quarterback’s lower legs.

Brady works fanatically on exercises to maintain flexibility, a trait he says keeps him healthy. “I just fall the right way,” he told the Globe near the beginning of his career, when he was 26. “Being limber, my body can contort in different ways.”

He expanded on those thoughts in a 2015 New York Times story: “If there’s so much pressure, just constant tugging on your tendons and ligaments, you’re going to get hurt… Like with a kid, when they fall, they don’t get hurt. Their muscles are soft. When you get older, you lose that.” Brady is also known for his obsessive “anti-inflammation” diet, which avoids white sugar and flour, dairy and caffeine, as well as things widely considered healthy, such as most fruit, tomatoes, peppers, and mushrooms, his personal chef told Boston.com last year.

Injuries can compound as a quarterback ages, said Moon, who was in the NFL until age 44. Moon considers himself “very lucky that I only had a couple of different fractures. I never had anything major, like a major knee injury or major shoulder separation in my passing arm. You look at Peyton Manning and the neck surgeries he had over his career. It was amazing he was able to come back and play the way he did. But at some point that’s going to catch up with you. And you saw when he kind of hit the wall, it went fast.” Manning retired at 39 after a 2015 season in which his team won the Super Bowl but he finished with a career-low passer rating.

Brady has suggested he wants to play until he’s nearly 50. That’s probably too old, Moon said, but he thinks Brady and Drew Brees, the 38-year-old New Orleans Saints quarterback who led the NFL in passing yards this season, “could definitely play until they’re around 45.”

“There’s no reason they shouldn’t be able to play at a high level longer — you can if you take care of yourself,” Moon said. “That’s one of the reasons I think Tom has been so successful. His training regimen is second to none; the way he takes care of himself, the way he eats, all the things he keeps out of his body, the way he trains, how he works on his fundamentals and techniques all offseason long. And he’s one of the most competitive people you ever want to meet. You combine all those things together and there’s a reason this guy is still playing at the top of his game.”

Illustrations by Alex Hogan.