Chaim Bloom is transforming the Red Sox. What does the future hold?

The chief baseball officer is entering his fourth season at the helm. With the 2023 season upon us, there remain more questions than answers about the team’s strategy and future.

Offseasons often come with themes. The Red Sox’ came in the form of a question.

“What are they doing?”

Many people — from baseball insiders to fans — have struggled to identify the unifying strand in the team’s efforts to build its 2023 roster to improve upon a 78-84 last-place disappointment in 2022.

Franchise cornerstone Xander Bogaerts departed in free agency before the front office made a back-up-the-truck $331 million commitment to ensure Rafael Devers did not follow suit.

The Red Sox did little to pursue a standout class of stars in free agency after Bogaerts left for San Diego, opting not to play ball with the likes of Aaron Judge, Trea Turner, Carlos Correa, Brandon Nimmo, Justin Verlander, and Carlos Rodón.

Instead, they guaranteed $90 million to Japanese star Masataka Yoshida, the 10th-largest amount guaranteed for a free agent or posted player, with an additional $15.4 million sent to Orix, Yoshida’s Japanese team.

Beyond that, the Sox made several modest investments in free agency, signing seven others to short guaranteed deals, and turning over a sizable chunk of the roster for a fourth straight offseason.

The moves elicited more questions:

· Is massive roster turnover — and with it a less-recognizable team for fans — a constant?

· Are the Red Sox still top spenders?

· Are they still in the business of acquiring stars?

· How much has the farm system actually improved?

Those questions point toward larger ones: Who are the Red Sox under chief baseball officer Chaim Bloom and where are they going?

Red Sox on Opening Day, 2012-2023

Players listed in order of when they first appeared on a Red Sox Opening Day roster, including key players who were on the injured list to begin the season.

- Clay Buchholz

- Jon Lester

- Josh Beckett

- Daniel Bard

- Felix Doubront

- Alfredo Aceves

- Matt Albers

- Scott Atchison

- Michael Bowden

- Mark Melancon

- Franklin Morales

- Vicente Padilla

- Justin Thomas

- Jarrod Saltalamacchia

- Adrian Gonzalez

- Dustin Pedroia

- Mike Aviles

- Kevin Youkilis

- Ryan Sweeney

- Jacoby Ellsbury

- Cody Ross

- Nick Punto

- Darnell McDonald

- Kelly Shoppach

- David Ortiz

- Rich Hill

- Daisuke Matsuzaka

- Andrew Miller

- Carl Crawford

- Andrew Bailey

- Chris Carpenter

- Ryan Kalish

- John Lackey

- Ryan Dempster

- Joel Hanrahan

- Clayton Mortensen

- Junichi Tazawa

- Koji Uehara

- Mike Napoli

- Jose Iglesias

- Will Middlebrooks

- Jackie Bradley Jr.

- Shane Victorino

- Jonny Gomes

- Pedro Ciriaco

- Mike Carp

- David Ross

- Daniel Nava

- Craig Breslow

- Stephen Drew

- Jake Peavy

- Burke Badenhop

- Chris Capuano

- Edward Mujica

- Brandon Workman

- A.J. Pierzynski

- Xander Bogaerts

- Grady Sizemore

- Jonathan Herrera

- Steven Wright

- Wade Miley

- Rick Porcello

- Justin Masterson

- Tommy Layne

- Alexi Ogando

- Robbie Ross Jr.

- Anthony Varvaro

- Ryan Hanigan

- Pablo Sandoval

- Allen Craig

- Mookie Betts

- Brock Holt

- Hanley Ramirez

- Sandy Léon

- Edwin Escobar

- Joe Kelly

- Christian Vázquez

- David Price

- Matt Barnes

- Craig Kimbrel

- Noe Ramirez

- Rusney Castillo

- Travis Shaw

- Blake Swihart

- Chris Young

- Eduardo Rodriguez

- Carson Smith

- Chris Sale

- Heath Hembree

- Fernando Abad

- Robby Scott

- Ben Taylor

- Mitch Moreland

- Andrew Benintendi

- Steve Selsky

- Roenis Elias

- Josh Rutledge

- Tyler Thornburg

- Drew Pomeranz

- Hector Velázquez

- Brian Johnson

- Marcus Walden

- Bobby Poyner

- Rafael Devers

- J.D. Martinez

- Eduardo Núñez

- Marco Hernandez

- Austin Maddox

- Nate Eovaldi

- Colten Brewer

- Ryan Brasier

- Sam Travis

- Steve Pearce

- Jeffrey Springs

- Dylan Covey

- Matt Hall

- Martín Pérez

- Phillips Valdez

- Austin Brice

- Ryan Weber

- Josh Osich

- José Peraza

- Alex Verdugo

- Kevin Plawecki

- Jonathan Lucroy

- Jonathan Araúz

- Michael Chavis

- Tzu-Wei Lin

- Kevin Pillar

- Josh Taylor

- Darwinzon Hernandez

- Garrett Richards

- Nick Pivetta

- Tanner Houck

- Adam Ottavino

- Garrett Whitlock

- Matt Andriese

- Hirokazu Sawamura

- Bobby Dalbec

- Kiké Hernández

- Franchy Cordero

- Hunter Renfroe

- Marwin Gonzalez

- Christian Arroyo

- Michael Wacha

- Kutter Crawford

- Matt Strahm

- Austin Davis

- Jake Diekman

- Hansel Robles

- Trevor Story

- James Paxton

- Corey Kluber

- Kenley Jansen

- Chris Martin

- Joely Rodríguez

- Richard Bleier

- Zack Kelly

- John Schreiber

- Wyatt Mills

- Reese McGuire

- Triston Casas

- Masataka Yoshida

- Adam Duvall

- Justin Turner

- Rob Refsnyder

- Yu Chang

- Raimel Tapia

- Adalberto Mondesi

- Brayan Bello

- Connor Wong

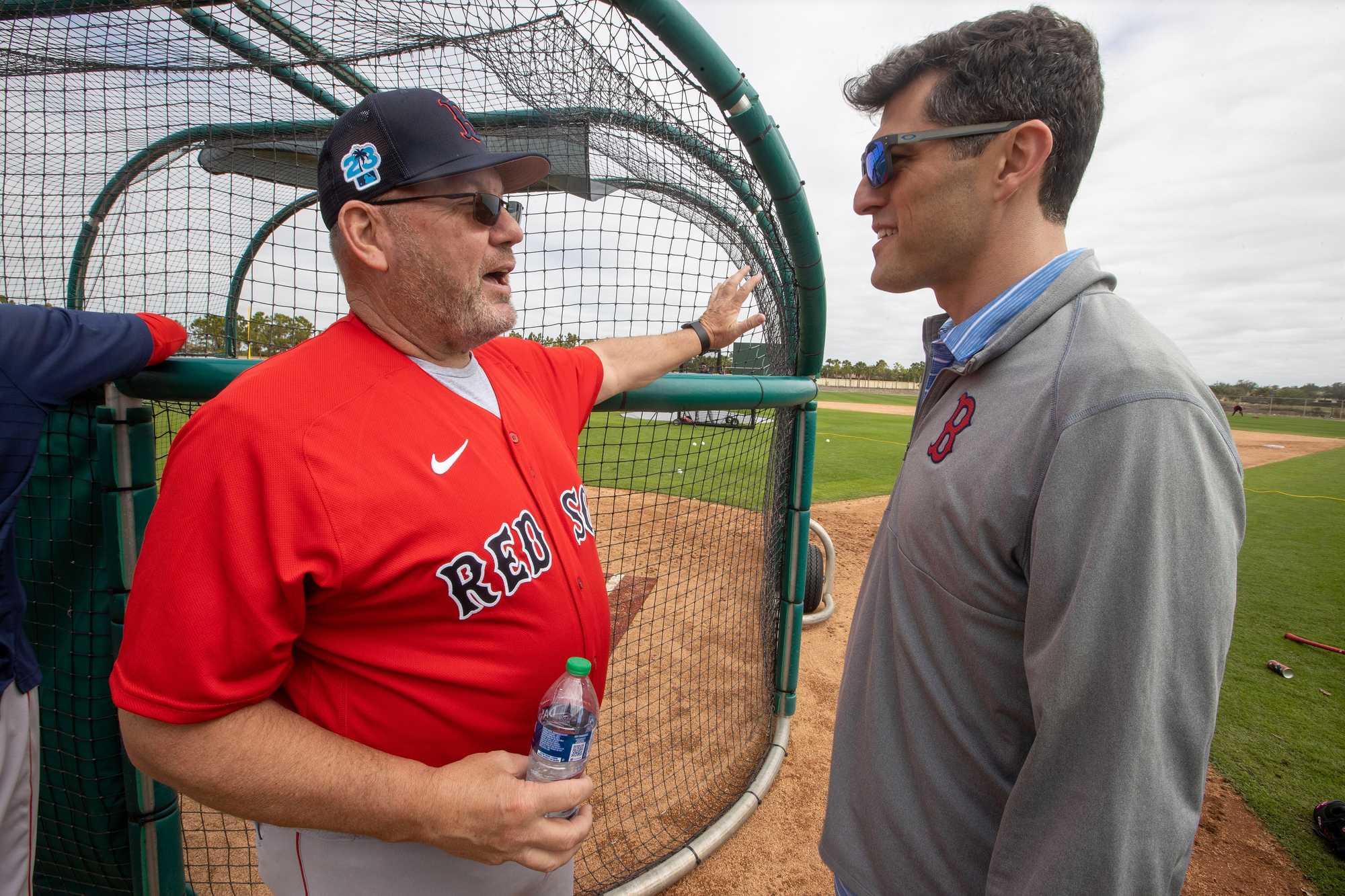

Three bosses, three approaches

The Red Sox won two World Series under three different leaders from 2012 to 2023. Ben Cherington took over in the 2011 offseason and relied mostly on a mix of homegrown and free-agent veterans to win in 2013. Dave Dombrowski bet big on stars to win in 2018. In 2021, Chaim Bloom’s Sox made it within two wins of the World Series.

One size doesn’t fit all

Cherington inherited a team with a number of long-term commitments and a wave of young talent in the distance in the minors. Dombrowski arrived as the group that had developed under Cherington was starting to establish itself, and had the freedom to bring in stars. Bloom inherited a veteran roster that had recently won a title but was at risk to decline, as well as a farm system with little top-end talent.

2012

Cherington started his tenure with several homegrown standouts — Dustin Pedroia, Jon Lester, Clay Buchholz, Jacoby Ellsbury, and Kevin Youkilis — who'd been supplemented with several high-priced deals for top-end talents like Adrián González, Carl Crawford, John Lackey, and Josh Beckett. But the veterans were in decline, resulting in a mid-year roster- and payroll-resetting blockbuster to deal González, Crawford, and Beckett to the Dodgers.

Homegrown WAR: 8.4

2013

While the trade had freed a huge amount of money, the Sox opted to spread the wealth, moving aggressively to re-sign David Ortiz before acquiring mid-tier free agents on one- to three-year deals. Nearly all of those additions hit on the high end of their projections, the team's veteran holdovers excelled, and rookies Xander Bogaerts and Brandon Workman made immediate impacts. The Sox won an improbable title.

Homegrown WAR: 25.4

2014

The Red Sox allowed a few key contributors from the previous year to depart, with the team mostly acquiring seat warmers to keep spots occupied while waiting for some top minor leaguers to join Bogaerts. But the magic of 2013 didn't repeat itself. Veterans regressed and callups struggled, resulting in a last-place finish and mid-year selloff of Lester, Lackey, and Andrew Miller.

Homegrown WAR: 10.9

2015

A patchwork starting rotation performed like ... a patchwork starting rotation, while high-priced signings Hanley Ramirez and Pablo Sandoval proved immense disappointments — a combination that condemned the Sox to a second straight last-place finish. Cherington left in August, and Dombrowski was brought in. Bogaerts and Betts flourished after struggling in 2014, while several other players — including Jackie Bradley Jr. and Eduardo Rodriguez — emerged down the stretch.

Homegrown WAR: 18.0

2016

Dombrowski moved quickly to address what he saw as a limited number of holes, anchoring his offseason around the signing of free-agent starter David Price to a record-setting contract and a trade for Craig Kimbrel. Betts, Bogaerts, and Bradley all joined Ortiz, in his farewell season, as All-Stars. Rick Porcello, meanwhile, took a Cy Young turn, as the Sox reopened their window of title contention by winning the AL East.

Homegrown WAR: 26.8

2017

The Sox tried to thread the needle, working to shed payroll to duck under the luxury tax threshold while still maintaining championship ambitions. There was the bull's-eye acquisition of Chris Sale for four prospects, and the ill-fated addition of Tyler Thornburg. Despite the struggles of young stars and a tense environment with the unraveling relationship between Dombrowski and manager John Farrell, the Sox — aided in part by mid-year callup Rafael Devers — reached the playoffs for the second straight year.

Homegrown WAR: 21.9

2018

Dombrowski was not deterred by two straight ALDS eliminations, and thought the Red Sox needed minimal upgrades. First, he hired Alex Cora to change the team's culture. Then, in February, he signed J.D. Martinez to a five-year, $110 million deal. Martinez was key, Betts became an MVP, Bogaerts added power to his game, and Andrew Benintendi emerged as a supporting standout. The Sox rolled to a 108-win season, then marched through the playoffs for the team's fourth title of the century.

Homegrown WAR: 24.9

2019

Though he explored possible trades of Bogaerts and Porcello, Dombrowski essentially opted to bring back the band to defend its title, adding just one player from outside the organization (reliever Colten Brewer). But most of the players who'd had career years in 2018 were unable to reproduce. The Sox had no prospects ready, and feared a long-term franchise downturn. Dombrowski was fired in September.

Homegrown WAR: 28.1

2020

Bloom arrived with a mandate to reconfigure the roster and payroll while rebuilding the young talent base. First, there was the painfully drawn-out trade of Betts and Price to the Dodgers. Porcello walked in free agency, Sale underwent Tommy John surgery and Eduardo Rodriguez suffered from myocarditis. The Sox were left with a pitching staff ill-suited to handle major league lineups, and went with a revolving door of pitchers and position players to little effect. The Sox finished last in the pandemic-shortened season.

Homegrown WAR: 5.5 (60-game season)

2021

To address several needs, the Sox took a number of routes: They took righthander Garrett Whitlock from the Yankees in the Rule 5 draft, made a separate trade with the Yankees to land reliever Adam Ottavino, and signed several free agents to one- and two-year deals, most notably Kiké Hernández and Hunter Renfroe. Those acquisitions gelled with holdover stars Bogaerts and Devers, and with full, healthy seasons from Nate Eovaldi and Rodriguez, the Red Sox made a charge to the ALCS.

Homegrown WAR: 11.9

2022

After getting within two wins of the World Series, Bloom signed Trevor Story to a six-year, $140 million contract. But injuries limited Story to 94 games, and the Sox' pair of turn-back-the-clock moves — trading to reacquire Bradley coming off a career-worst year and signing Travis Shaw to a minor league free agent deal — proved disappointing. The rotation was beset by injuries and the bullpen proved a weakness as the Sox endured another last-place finish.

Homegrown WAR: 13.4

2023

Bogaerts — the last holdover from the 2013 championship team — turned down a six-year offer from the Sox and left for the Padres in free agency. Only Devers, Sale, and Ryan Brasier remain from the 2018 title team. The Sox did commit $331 million to Devers for 11 years, giving the team its anchor into the future, and signed Masataka Yoshida to a five-year, $90 million contract. The Sox otherwise rounded out its projected Opening Day roster largely with players signed to one- and two-year deals.

The backdrop

When Bloom took over in October 2019, the Red Sox were a year removed from their fourth championship of the 21st century. Dave Dombrowski had been fired a month and a half earlier, and the team was in what ownership saw as a perilous position.

The roster featured immense talent and name recognition, but at a cost: Mookie Betts, Chris Sale, David Price, J.D. Martinez, Bogaerts, and Devers were all going to make at least $20 million in 2020.

The payroll in 2019 was the highest (by far) in team history and the highest in the majors that season, but the Sox sputtered to an 84-78 record. Team officials had accepted that Betts was certain to reach free agency. The farm system that had produced an incredible homegrown generation was ranked dead last.

The Sox feared age and injuries would negatively impact the rest of the roster. There were cautionary tales: The Giants, who won their third title in five years in 2014 before finishing 20 games below .500 from 2015-19; the Phillies, who won a World Series in 2008 and then missed the playoffs from 2012 until 2022; and the Tigers, who followed four straight postseason berths from 2011-14 by going 70 games below .500 from 2015-19.

“We could drive right off that cliff — you guys have seen big-market teams do it before — and end up rebuilding for half a decade,” Bloom said in response to a hail of boos from fans this past January. “That can’t happen in Boston.

“So what we had to do was find a way to turn that car around before we drove off that cliff.”

One thing was paramount for the U-turn: restoring the farm system, making it robust enough that it could constantly replenish the roster. The most efficient path to an elite farm system comes from tanking, but the Sox didn’t want to take that approach.

The Sox believed they had the worst of all worlds — a large payroll with most of the money concentrated in aging stars, plus a growing number of holes. With the hiring of Bloom, they planned to keep some of their most recognizable stars but accepted that they would part with others while trying to forge a more complete team.

“We had a team that had a lot of recent success but was the most expensive team not only in this division, but in Major League Baseball, and was very clearly not the class of the division anymore,” said Bloom. “And also, industry consensus was that the young talent base was near the bottom of the industry.”

Emblematic of the change the Red Sox have undergone under Chaim Bloom are the departures of Mookie Betts to the Dodgers and Xander Bogaerts to the Padres — two homegrown stars who had been franchise cornerstones. (Christian Petersen/Getty Images)

Thus, Bloom and the Sox made the brutal choice that will forever frame his tenure in Boston — trading Betts to the Dodgers in February 2020, before he reached free agency.

The Sox were able to create payroll space and start rebuilding the talent base by landing outfielder Alex Verdugo and minor leaguers Jeter Downs and Connor Wong. The decision was meant to get them beyond a boom-and-bust cycle that characterized the 2010s — a decade of two championships, four AL East titles, and three last-place finishes.

Instead, Bloom’s first three seasons have consisted of a pair of last-place finishes sandwiched around a surprise run to the ALCS in 2021. The Sox are four games over .500 (194-190) in the three years, a .505 winning percentage that ranks 16th in the big leagues.

On one hand, team officials view the 2021 run — fueled by the signing of a large number of free agents — as payoff for the decision not to rebuild while taking a flexible approach to roster building.

On the other, the Red Sox have now finished last five times in the past 11 seasons — most in the majors since 2012.

As the roster churns

A common theme to Bloom’s Red Sox rosters is the considerable year-over-year turnover — a marked contrast to the Dombrowski era, when an offseason might consist of a handful of moves.

The 2018 Opening Day roster featured one player — J.D. Martinez — who was new to the organization. Same with the 2019 Opening Day team (Colten Brewer).

Since Bloom’s arrival, the Red Sox have had 13 players who were new to the organization on Opening Day in 2020; nine new players in 2021; and eight in 2022. There’s a good chance that 10 newcomers will be on the roster (or injury list) when the season begins Thursday.

It’s not just you: Yes, the Red Sox use a lot of players

The number of unique players used per game by the Red Sox grew by 54 percent in the three years Chaim Bloom has been general manager compared with the three years prior. That increase is fourth highest across the major leagues over that time frame.

Percentile per column

- 1st

- 50th

- 99th

| 2017-19 | 2020-22 | ’17-19 | ’20-22 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Team | Hit. | Pit. | Total | Hit. | Pit. | Total | PPG | PPG | Pct. Ch. |

| Angels | 53 | 94 | 147 | 54 | 92 | 146 | 0.3 | 0.38 | 26% |

| Astros | 33 | 68 | 101 | 36 | 78 | 114 | 0.21 | 0.3 | 43% |

| Athletics | 43 | 87 | 130 | 53 | 73 | 126 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 23% |

| Blue Jays | 52 | 100 | 152 | 42 | 97 | 139 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 16% |

| Braves | 46 | 89 | 135 | 44 | 87 | 131 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 23% |

| Brewers | 41 | 86 | 127 | 44 | 86 | 130 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 30% |

| Cardinals | 40 | 75 | 115 | 38 | 83 | 121 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 34% |

| Cubs | 36 | 84 | 120 | 58 | 100 | 158 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 67% |

| D-backs | 42 | 72 | 114 | 45 | 92 | 137 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 52% |

| Dodgers | 44 | 80 | 124 | 37 | 88 | 125 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 28% |

| Giants | 56 | 79 | 135 | 54 | 82 | 136 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 28% |

| Guardians | 46 | 73 | 119 | 46 | 67 | 113 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 20% |

| Mariners | 53 | 108 | 161 | 51 | 93 | 144 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 13% |

| Marlins | 44 | 76 | 120 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 58% |

| Mets | 49 | 86 | 135 | 59 | 91 | 150 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 41% |

| Nationals | 40 | 83 | 123 | 51 | 87 | 138 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 42% |

| Orioles | 49 | 87 | 136 | 45 | 97 | 142 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 32% |

| Padres | 42 | 87 | 129 | 51 | 85 | 136 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 33% |

| Phillies | 46 | 88 | 134 | 41 | 90 | 131 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 24% |

| Pirates | 40 | 78 | 118 | 57 | 94 | 151 | 0.24 | 0.39 | 62% |

| Rangers | 38 | 90 | 128 | 54 | 84 | 138 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 36% |

| Rays | 57 | 86 | 143 | 39 | 99 | 138 | 0.29 | 0.36 | 22% |

| Reds | 43 | 81 | 124 | 48 | 88 | 136 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 39% |

| Red Sox | 33 | 75 | 108 | 43 | 88 | 131 | 0.22 | 0.34 | 54% |

| Rockies | 34 | 71 | 105 | 36 | 71 | 107 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 30% |

| Royals | 41 | 82 | 123 | 41 | 85 | 126 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 30% |

| Tigers | 40 | 85 | 125 | 42 | 79 | 121 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 23% |

| Twins | 36 | 91 | 127 | 43 | 93 | 136 | 0.26 | 0.35 | 36% |

| White Sox | 40 | 83 | 123 | 40 | 71 | 111 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 14% |

| Yankees | 46 | 81 | 127 | 42 | 86 | 128 | 0.26 | 0.33 | 28% |

This made the Red Sox less recognizable to longtime fans. Is turnover a feature or bug? Maybe both.

Take the Astros and Dodgers, who have resided atop the sport recently. Neither has been afraid to let stars walk. Houston let Justin Verlander, Carlos Correa, George Springer, and Gerrit Cole leave in successive offseasons, replacing them with young players from its system. The Dodgers saw shortstops Corey Seager and Trea Turner depart in back-to-back winters and cut ties with franchise stalwart Justin Turner.

The Sox appear committed to some degree of roster transformation while looking for upgrades and creating opportunities for players to establish themselves. But Bloom is uncomfortable with the number of needs they’ve had to address with players outside the organization.

“To say everybody’s just going to be here forever, that’s not realistic,” said Bloom, “and frankly, I don’t think that’s what we should want. I do think part of the reason the organization has won as much as it has over the last two decades is because it has been unafraid to make tough decisions that don’t feel great in the moment.”

Read more | See which teams our staff predicts will make the playoffs

But he has optimism about the future.

“I think it’s important for an organization, for a fan base, especially in Boston, to see and feel more continuity than I think we’ve been able to have them feel over the last couple of years,” he said. “I don’t anticipate change as jarring as what we’ve had the last three years going forward. I think, I hope that that ends up being a pretty unique period here.”

Are the Red Sox still big spenders?

Bloom was hired from the small-budget Rays, a former association often caricatured as a plan to draw down the team’s payroll. Trading Betts — motivated in no small part by the salary dump of David Price — did little to challenge those perceptions.

Yet the more recent reality suggests Bloom is spending in a fashion that is more in line with typical team behavior.

In 2022, the Red Sox carried a payroll (as calculated by MLB for luxury tax purposes) of just under $233 million — slightly above the $230 million threshold that resulted in a tax bill. It marked the eighth time in the last 16 years the Sox had spent beyond the threshold.

In 14 of those 16 seasons, the Sox carried a payroll within 11 percent of the tax threshold. In nine of them, including both 2021 and 2022, they were within 5 percent.

They have been in the top six in payroll for all but one of the last 16 years, and have led the league in spending twice, both times under Dombrowski.

Putting the Red Sox’ spending into context

The Red Sox have ranked among the six highest-spending teams in MLB in 15 of the past 16 seasons. They could drop this season in large part because many other teams are spending big.

Year

Over league average

Relative to luxury tax

Rank

2007

2

2008

6

2009

3

2010

2

2011

3

2012

2

2013

3

2014

5

2015

3

2016

5

2017

6

2018

1

2019

1

2020

8

2021

6

2022

5

The 2023 Sox project to have a payroll of roughly $220 million — a number that is likely to edge closer to this year’s $233 million tax threshold with space reserved for preseason and in-season roster additions as well as signings and callups. While Sox officials declined to discuss the payroll commitments, there’s a good chance they will finish the year within 5 percent of the threshold.

Sox president and CEO Sam Kennedy said principal owner John Henry, who also owns the Globe, and chairman Tom Werner maintain their commitment to spend on the team, and remain open to adding payroll this year.

“What you’ve seen is a commitment to spending in the top of baseball. That’s not going to change,” said Kennedy. “Are we going to add another $100 million or $200 million to the 2023 Boston Red Sox? No we’re not.

“But John and Tom have always demonstrated a willingness to adjust the payroll budget on the fly. That’s historically true. We’re going to have the major league payroll to be competitive. We’ve had it and will continue to have it.”

The issue? The Red Sox’ steady spending comes at a time when a growing number of teams have increased their roster investments.

A record seven teams — the Mets, Yankees, Padres, Phillies, Dodgers, Blue Jays, and Braves — seem likely to spend past the tax line in 2023. The Cubs, Astros, and Angels project to carry payrolls near or just above the Sox’ season-opening projection.

It’s possible the 2023 Sox will finish with their lowest payroll rank in Henry and Werner’s tenure.

At a certain point, payroll size is ultimately less important than whether money is well-spent. The last four teams to win the World Series stayed under the luxury tax. Large payrolls can contribute to success but don’t guarantee it.

The Sox know that well. In 2018, they were the most expensive World Series winner in baseball history. In 2022, they were the most expensive last-place finisher in baseball history.

Are they still trying to acquire stars?

The Red Sox haven’t always been good this century. But they’ve almost always had multiple cornerstone players who connected fans to the franchise’s accomplishments and ambitions.

That matters. Stars don’t guarantee titles, as the Mike Trout/Shohei Ohtani Angels have made clear, but World Series are rarely won in their absence. That’s certainly been true of the Sox.

“Star players win championships,” said Kennedy.

Meanwhile, the Sox have confronted grim consequences when they have lone stars rather than constellations.

According to Baseball Prospectus, there have been five seasons this century in which the Sox had fewer than two players reach at least a 4-win WAR plateau: 2022, 2020, 2015, 2014, and 2012. A common theme exists for those teams: They all finished last in the AL East.

This year, the Prospectus 50th percentile (midpoint) projections feature nary a Red Sox player reaching 4.0 WAR. Devers (3.8) and Yoshida (3.7) — who received the largest commitments from the Sox this winter — are closest. The team does not have a pitcher whose 50th percentile projection ranks among the top 75; Chris Sale’s 1.4 WAR projection ranks 76th.

After Xander Bogaerts left in free agency, the Red Sox made a big effort to retain Rafael Devers. Their largest offseason addition entering the 2023 season was Masataka Yoshida from Japan. (Devers: John Tlumacki/Globe Staff. Yoshida: Megan Briggs/Getty Images)

Have the Red Sox been too cautious in pursuing upgrades from outside the organization under Bloom?

The Devers contract represented a landmark, evidence that the Sox will spend at the highest levels for top talent, particularly when that commitment doesn’t stray too far beyond a player’s prime.

Still, the team’s biggest open-market move has been for Trevor Story, signed to a six-year, $140 million deal in March 2022 — tied for the 17th largest free-agent guarantee in baseball since Bloom joined the Sox. Beyond their unsuccessful effort to retain Bogaerts, the Sox weren’t meaningfully involved in the top of this offseason’s free-agent market.

Free agency has always been a risky form of team-building. Players are signed for the peak years at the front end of deals, and contracts usually come with diminishing returns at the back end. The market has changed, with more deals in the nine-to-13-year range instead of six-to-seven — giving far more chances for a contract to zero out.

Teams that believe they’re built to win in the short term, with well-constructed rosters and a base of young, inexpensive players, tend to be more inclined to take those risks in pursuit of stars. The Sox are moving closer to that, but aren’t there yet.

Advertisement

“There are different ways of going about trying to build a championship-caliber team,” said GM Brian O’Halloran. “Some of it depends on the state of your organization and your talent base, and some of it might just be choices that the department or the department leaders make.”

Over the last three offseasons, the Sox have felt like they’ve had too many roster needs to lock an enormous chunk of their budget in a single player beyond his likely years of productivity. That hasn’t meant total risk avoidance — they spent to land Story and Yoshida, viewing both as elite talents — but it has meant staying below the top of the market.

“Obviously, you’d love to have a star at every position,” said Bloom. “But a complete roster matters, so you want both [stars and depth]. If you are leaving holes on your roster, it doesn’t matter how many headlines you grabbed. That will come back to bite you.”

Eventually, the Sox envision a fuller roster entering the offseason — ideally one with several contributors who are early in their big league careers — that permits bigger risks.

“Hopefully, as we go forward, the bigger investments we make will be consistently backed up by more complete rosters,” said Bloom. “That’s what consistent winning looks like.”

They have started to assemble young talent. The arrivals of pitchers Garrett Whitlock and Tanner Houck in 2021 made it easier to sign Story to his six-year deal. The emergence of first baseman Triston Casas and pitcher Brayan Bello made the Red Sox more comfortable signing Devers to his landmark deal.

The more productive the player development system, the more comfortable the Sox will become with taking bigger swings in pursuing players.

Has the farm system improved?

In 2002, Theo Epstein took over as general manager of the Red Sox and said he would create a scouting and player development machine. Everything the current Red Sox are trying to accomplish relies on a 2.0 version of the system that helped them win their first World Series in 86 years.

The goal: a gushing talent pipeline that supplies the big league team with both stars and depth, with enough talent to round out the roster but still support aggressive trades in addition to free agency.

They aren’t there yet.

Tending to the farm

The Red Sox’ minor-league system was wiped out during the Dombrowski era – but, of course, the team also won a World Series. This season, the team has its best ranking (according to Baseball America) since 2016. Hover/touch the circles below to see prospect names.

Year

Baseball America Top 100 prospects

(With ranking. Higher prospects shaded red. Lower prospects shaded orange.)

Red Sox farm system rank

(Where Boston ranked among the 30 MLB teams.)

15 Baseball America Top 100 prospect (Higher prospects shaded red. Lower prospects shaded orange.)

Red Sox farm system rank

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

Baseball America pegs the Sox as having the 10th-best farm system, with five top-100 prospects: Marcelo Mayer (2021 first-rounder), Casas (2018 first-rounder), Ceddanne Rafaela (2017 signee), Miguel Bleis (2021 international signee), and Yoshida, who is eligible for Rookie of the Year because he has never played in MLB. Publications that do not view Yoshida as a prospect have the Sox ranked closer to the middle of the pack.

“We’ve improved it significantly,” O’Halloran said. “It’s not where we hope and expect it to be in the future.”

There are signs that the Sox are doing a better job of developing players than they did a few years earlier.

Coaches and analysts have collaborated to help reshape the arsenals of Houck, Bello, and Kutter Crawford in ways that allowed them to become big league contributors. It’s the most promising period of homegrown pitcher development in more than a decade.

Both Casas and Rafaela have improved in the minors. Rafaela has gone from an off-the-radar prospect to a potential big league regular, and Casas will start at first base.

At the same time, some of the team’s developmental misses have been costly.

Jeter Downs and Jarren Duran have not developed as projected, prompting a desperate search for up-the-middle players this winter after Bogaerts departed.

Over the last three years, the Sox have been more active in trading for minor league talent than at any other point this century. But most of their acquisitions were for depth rather than shots at top-tier talent.

Getting Downs — a top-100 prospect when acquired from the Dodgers for Betts — was the biggest swing, and the Sox whiffed. He was lopped off the 40-man roster this offseason and claimed off waivers by the Nationals.

But long-term success relies less on individual performances and more on how the system develops players. The Red Sox had fallen behind in what many team officials describe as the arms race of development.

Since Bloom’s arrival, the Sox have focused on efforts below the surface, working to assemble the personnel, systems, and technology to become an organization that supplies the big league team with an unending talent pipeline.

Advertisement

The team’s championship run in 2018 was fueled by a golden generation of homegrown players. By the end of 2019, the Sox had a bottom-ranked farm system. To make matters worse, they felt they were behind organizations like the Dodgers, Astros, Yankees, and Rays when it came to how they developed players.

They had passionate coaches and teachers but didn’t have a pitching lab focused on pitch design, didn’t have the scale of technology to precisely track everything on the field, didn’t have the specificity of goals in player plans to instruct them on not only what they needed to work on but how they needed to do it.

Infrastructure building isn’t glamorous, but it is essential. And it’s been central to how the Sox have operated since Bloom’s arrival — particularly this winter, as they spoke increasingly about a goal of being the top player-development organization in the game, while operating as if they rank 30th to avoid complacency.

“We’ve done some internal evaluations, looking at ourselves and how we compare to other teams,” said farm director Brian Abraham. “We want to be the best. And I think this offseason represented us moving toward that direction.”

Where are the Red Sox going?

The true value of any improvements will come when the Red Sox have internal depth. In the meantime, they are trying to complement what they have with the right mix of free agents to field a contending team in the short term — so long as it doesn’t tie up too much payroll or too many roster spots when (or if) the young talent base they hope to cultivate is ready to contend for a title.

That approach worked in 2021 but flopped in 2022, and public projection systems are unkind to the 2023 Red Sox.

Fangraphs projects them at about .500, the lowest preseason win total projected for the Sox in the 11 years the website has evaluated the data. Baseball Prospectus sees an 80-win season. Both peg the Sox to finish in fourth.

One thing is for sure: Expectations are low

The Red Sox are projected to finish at .500 and in fourth in the AL East, according to Fangraphs — the lowest the Sox have been projected by the website. Here’s a look at the historic projections.

- Projected wins and division finish

- Actual wins and division finish

No one is surprised by the skepticism.

“We still are the ‘worst’ team in the division,” manager Alex Cora said. “Obviously somebody has to be the favorite and somebody has to be the underdog. And right now, we’re not the favorites.

“I saw what happened last year. If I’m in that business [of predicting], which I was, I’d be saying the same thing.”

Read more | Why projection systems don’t like the 2023 Red Sox

Members of the team still see paths for them to outperform expectations and contend in 2023. Good health for Chris Sale, precocious contributions from players such as Casas and Bello, a superstar turn by Devers, or a deep, disciplined lineup where the sum exceeds the parts could allow the Sox to surprise.

Still, many evaluators see the AL East as a two-tiered division, with the Yankees, Rays, and Blue Jays and their loaded rosters poised for a battle royale, and a clear talent gap separating those three clubs from the Red Sox and Orioles.

Where does Bloom go from here?

It’s premature to suggest the Red Sox can’t be a playoff team in 2023. But a wealth of things will have to go right for them to make another surprise run.

So, the obvious question: Is Bloom’s job in danger?

After all, his predecessors — Dombrowski and Ben Cherington — were replaced in their fourth seasons despite having World Series titles on their résumés.

“It comes down to wins and losses. That’s how we’re all judged,” said Kennedy. “But there’s a lot going on that we’re really proud of, and we continue to be committed to the approach that we have in terms of building a very strong minor league system and winning at the major league level all at the same time.”

Read more | Meet the players on the Red Sox’ 2023 Opening Day roster

Kennedy said there is a “strong belief and commitment” internally to the leadership team of Bloom, O’Halloran, and Cora, noting that at the end of 2021, Bloom was hailed for threading the needle of short- and long-term.

“There’s a lot of good things happening under the hood, and a lot of good things that we hope will be happening in plain daylight where everyone can see the results of Chaim and his team,” Kennedy said. “We’ll see what 2023 brings, but we have a high level of confidence in him and his staff.”

But the winds can shift.

Ownership was in close alignment with Cherington until it pivoted to a new leader while the Red Sox were mired in a third last-place season in four years, and just before the young core he’d cultivated flourished.

The Sox planned to extend Dombrowski in the wake of the 2018 World Series, but fault lines opened during the offseason that, in tandem with the disappointing 2019 campaign, led to his ouster.

Bloom, according to major league sources, is in the middle of the long-term contract he signed when he joined the Sox, one that includes at least one guaranteed year (as well as one or more team options) beyond the 2023 season. But that status doesn’t come with any guarantees.

Advertisement

Nor, Bloom believes, should it.

“I don’t want to talk about my own situation,” he said. “I just don’t. The way I view it is it shouldn’t matter to how I do my job.

“The first question I got when I rolled into camp here was ‘Do you think your job is on the line this year?’

“Really, the best answer I can give, which I should have given at that point in time, is I think it’s always on the line. If you’re not going after every day in this job like it’s the most important day of your career, then you’re probably not doing the job you should, and it should always come back to what’s the right thing for the Red Sox.”

So is he doing that? There are, Bloom believes, two ways of judging that question.

The first is binary: Did the team win the World Series the previous year or not?

The second is directional: Is the team closer to that goal at the end of any given year than at the start of it?

“The goal anywhere and certainly here should always be to win the World Series,” said Bloom. “Last year, we obviously didn’t pull off the winning part. I do think the organization still finished the year in a better position than it started.

“If we can win and keep winning while we keep improving the organization, that is the recipe for us getting where we want to go.”

Even if the Red Sox believe they have pulled back from the cliff, they haven’t yet arrived at the sport’s summit.

Credits

- Reporter: Alex Speier

- Editor: Katie McInerney

- Graphics, Design, and Development: John Hancock

- Copy editor: John Carney

- Audience engagement: Cecilia Mazanec and Jenna Reyes

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

© 2023 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC