Streets that put people first, not cars

Cities around the world are reconfiguring their urban grids to support local communities and economies. Boston should do it too.

March 7, 2021

Over the past year COVID-19 has forced dramatic changes in our communities, especially when it comes to outdoor public places. Gyms moved fitness classes into parks. Retailers found new opportunities for "sidewalk sales." Restaurants claimed parking spaces and roadways for outdoor dining service. And in the process, we've sensed how much better our cities and local economies can be after the pandemic.

We hear less traffic on city streets and are exposed to lower levels of harmful pollutants. And we’ve gained an entirely new way of thinking about space in our cities and towns.

Instead of viewing streets as spaces to move vehicles quickly through, what if we reimagined these valuable slices of real estate as places to build community, to connect disconnected neighborhoods, to encourage healthier lifestyles, to improve our neighborhoods’ air quality, and to support local economies?

New outdoor dining spaces in Boston. Courtesy of Jonathan Berk.

Superblocks

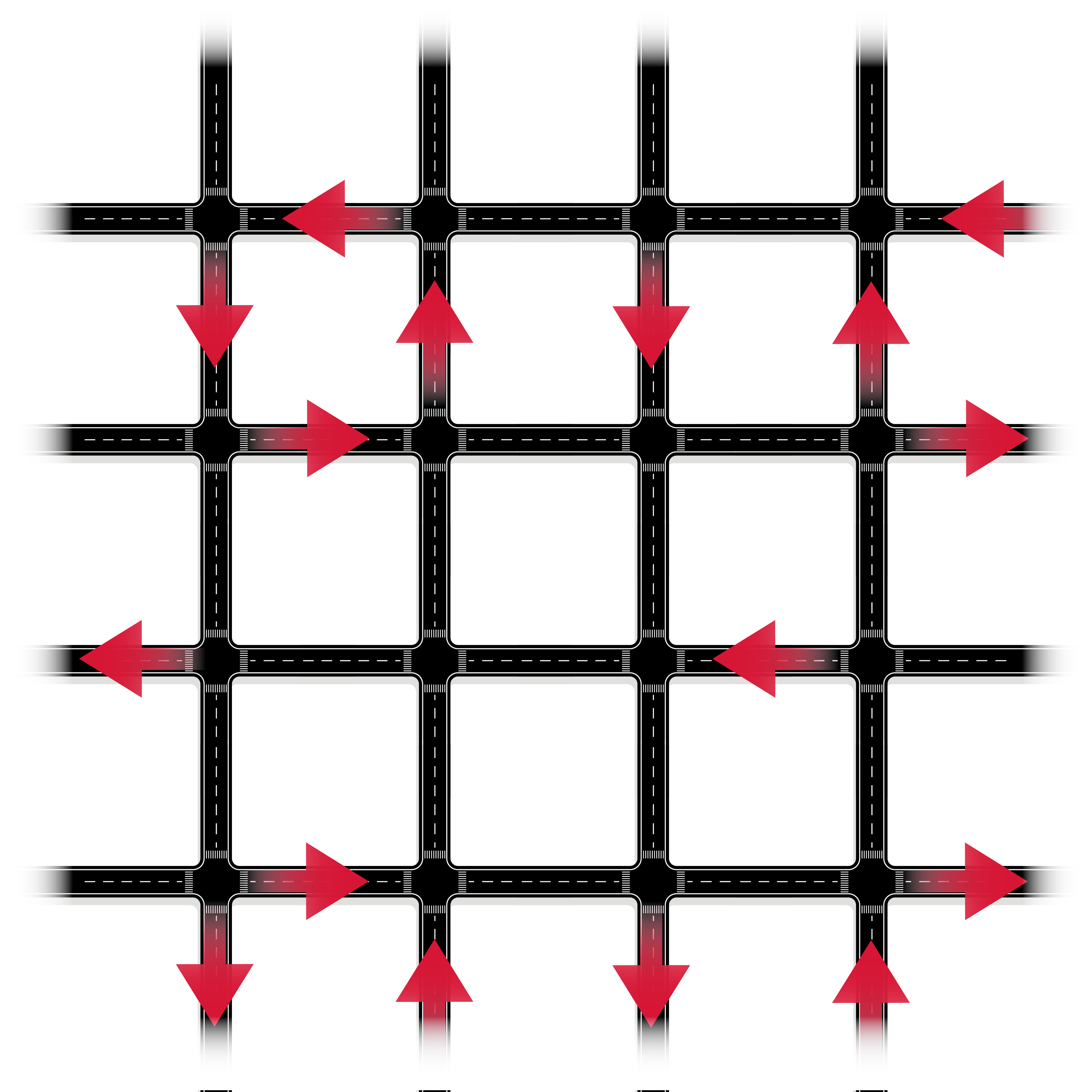

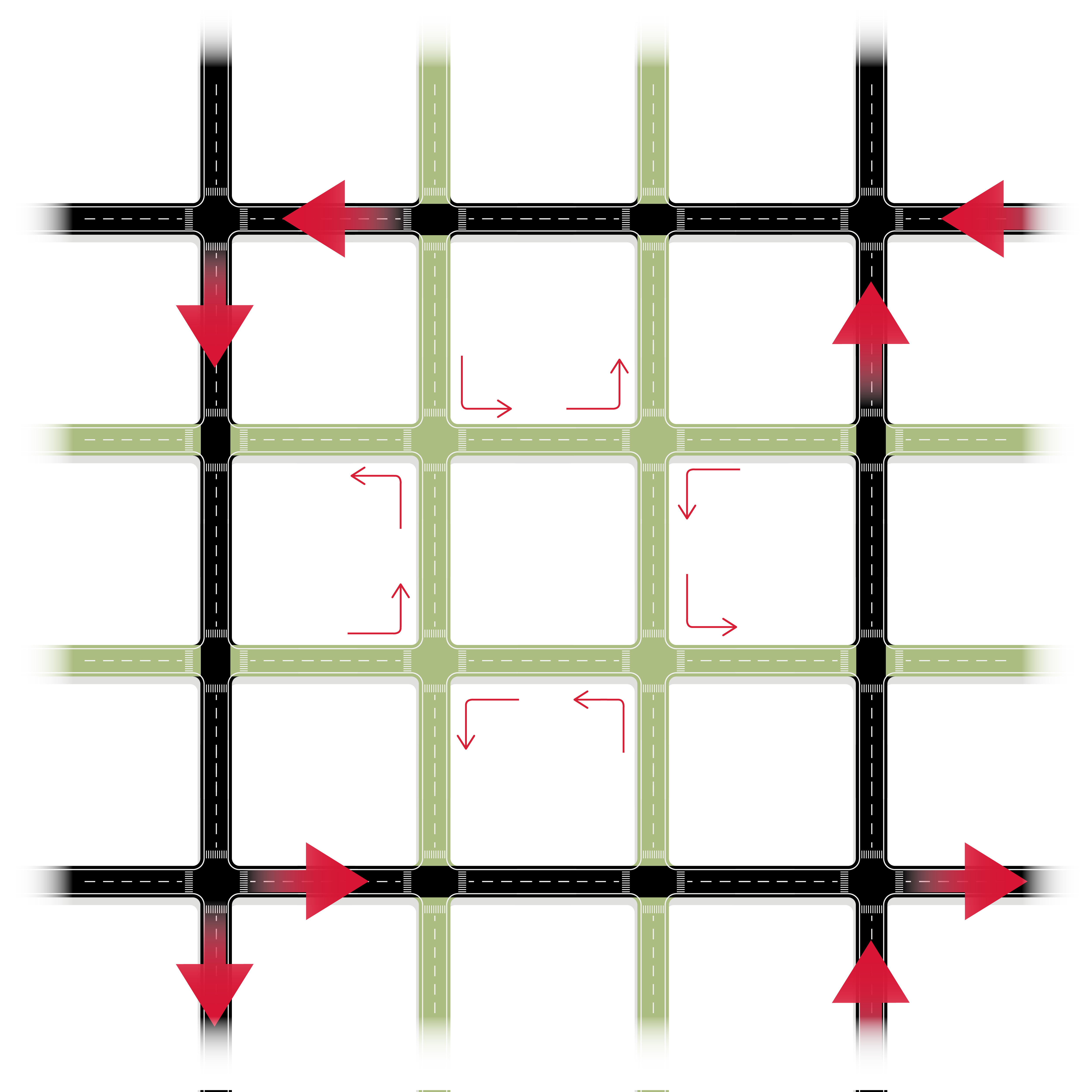

Barcelona, Spain, has been experimenting with exactly this, with a concept called the “superblock.” It combines several traditional city blocks into a more integrated whole. Major roads running on the outside of the superblock are designated for normal vehicle traffic and remain untouched, but the interior streets are restricted to local traffic only, with a dramatically reduced speed limit. These streets become a zone that is more amenable to cyclists, pedestrians, greenery, and outdoor commercial activity.

Traditional

Superblock

As Barcelona defines it, the plan is to create "mini neighborhoods" repurposed to "fill our city with life." "Our objective is for Barcelona to be a city in which to live," Janet Sanz, a city councilor in Barcelona, told the Guardian.

Residents on these streets get many health benefits: more room to exercise, less particulate matter and other pollutants in the air, and a lower risk of being injured by a car. Neighbors also have more ways to develop personal connections with one another.

People using redesigned streetscapes in Barcelona. Courtesy of @SuperillaP9 via Twitter.

Advertisement Continue reading below

In a landmark study in San Francisco in the 1970s, Donald Appleyard, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, compared three streets: one with 2,000 vehicles per day, one with 8,000, and one with 16,000. His research indicated that people living on the least-trafficked street had three times as many neighbors they would classify as friends as people on the busiest street had. Although much has changed about cities and people's social lives since Appleyard's research, we still encounter our neighbors on our streets in much the same way.

Boston's streets

I use Boston’s South End as an example of what the superblock treatment could do in the city because it’s where I live. I’ve walked and biked these streets for years, and I’ve discussed ideas of reusing our streets at length with neighbors and local business owners. I wouldn’t presume to suggest specific designs for other parts of town or other communities, because I believe that the best ideas for how to improve a neighborhood start from the ground up, though they can draw their inspiration from cities everywhere. My hope is that from Boston to Worcester and Springfield to Salem, people will consider ideas like superblocks and other types of street transformations through an equity lens. Alterations of public space can be geared toward strengthening the social fabric and local economies in neighborhoods that have traditionally seen disinvestment in their public spaces.

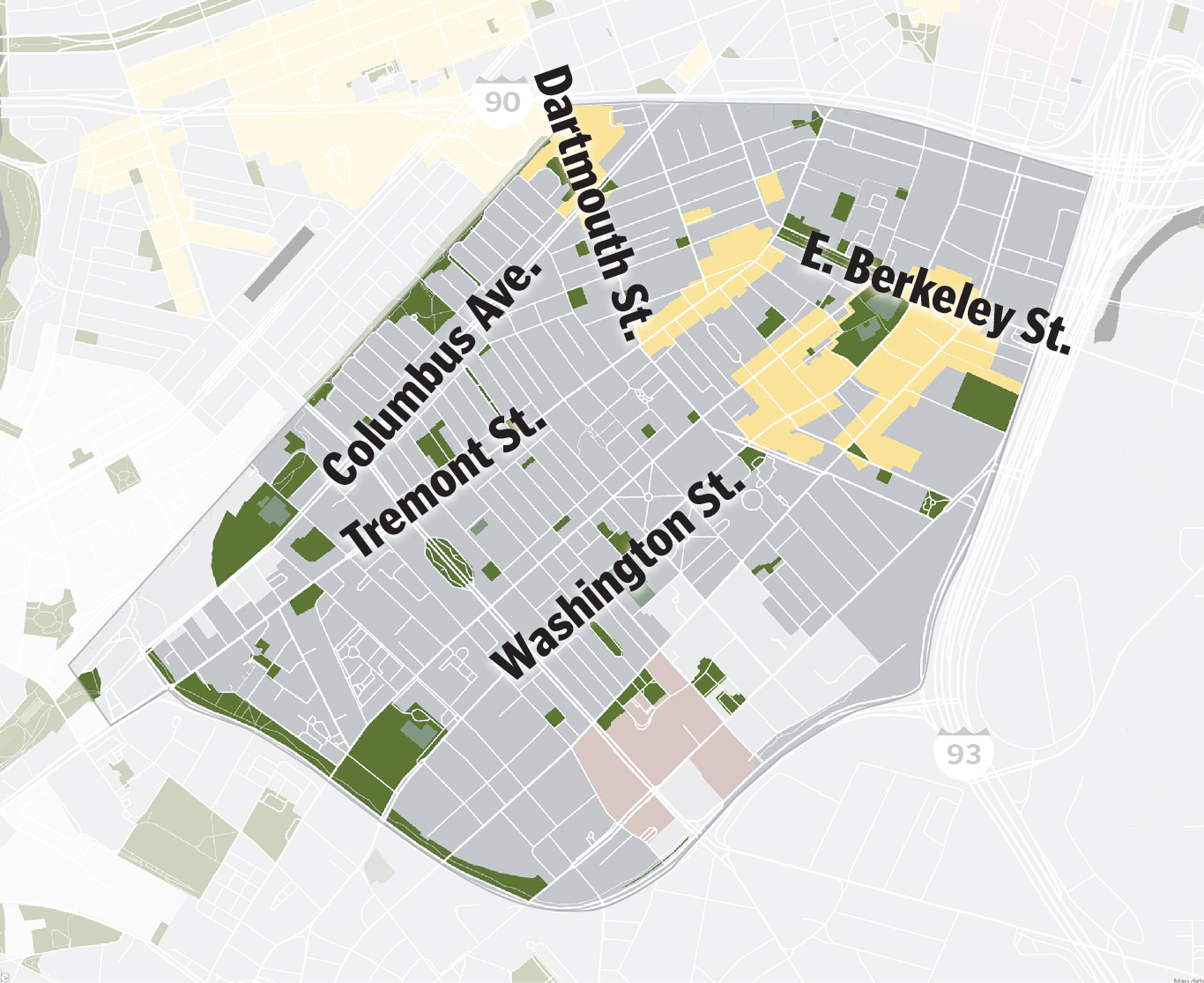

Boston's South End neighborhood.

I envision South End arterial streets remaining untouched, such as Washington Street, Tremont Street, and Columbus Avenue, along with through streets like East Berkeley and Dartmouth. These would be open to traffic as usual. Imagine that these streets form the borders of each superblock, and all nonlocal traffic gets pushed to them. Traffic into the neighborhood streets is limited to residents, visitors, customers, and deliveries — a rule made clear by signage at all entrances to the superblocks and reinforced with a posted speed limit of 5 mph, which signals that street space is now shared by pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers.

Let’s imagine as well that local traffic is directed in a U-shape into and out of the neighborhoods, freeing up space at intersections to create small parks while making it impossible for drivers to ignore the signage and use neighborhood streets as a cut-through to get around traffic.

Pavement markings, seating, and planters at the newly created intersection plaza spaces create gathering places within a few hundred feet of hundreds of residents’ homes.

With less traffic, streets are narrowed, opening up space for permanent outdoor dining, play areas for children, and small parks.

A section of Shawmut Street now and as it might look in a superblock, as rendered by Copley Wolff Design Group.

Superblocks will still contain ample parking spaces for residents, deliveries, and visitors to local businesses. It’s just that Waze and other traffic apps won’t recommend trips through the area as shortcuts to people going elsewhere.

Smaller-scale street transformations of the past year remind us that we’ve simply looked the other way for decades as one of our most valuable public assets has become the exclusive domain of the automobile, precluding so much opportunity for community activities and commerce. Just look at New York City, where live concerts and outdoor movie nights spontaneously popped up last summer, with residents bringing their own chairs outside. The city provided the space by decreasing traffic, and the void was filled by creativity, connectivity, and community.

The same thing can happen for hundreds of thousands of people across Massachusetts for whom the street outside their home serves as their front porch and is the only nearby space where they can easily meet their neighbors.

A movie night in a street in New York City. Courtesy of Kevin Stankiewicz.

Business prospects can rise in superblocks, too. More restaurants can offer outdoor dining. Other local businesses can use the increased street space for everything from sidewalk sales to farmers markets. This could be crucial for keeping neighborhood dollars in neighborhood businesses, building and sustaining local wealth.

And nonprofits might use these new outdoor spaces to help neighborhood kids with their homework.

As Janette Sadik-Khan, the former commissioner of the New York City Department of Transportation, said about transforming sections of Times Square into large pedestrian plazas: "It's possible to change your streets quickly. It's not expensive, it can provide immediate benefits, and it can be quite popular. You just need to reimagine your streets. They're hidden in plain sight."

Credits

Editor: Brian Bergstein

Design and development: Andrew Nguyen

Graphics: Heather Hopp-Bruce

©2021 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC