Unbowed

A generation of black youth in America struggle with Obama's legacy and their future

Written and reported by Akilah Johnson, with Jan Ransom

Visuals by Keith Bedford

Written and reported by Akilah Johnson, with Jan Ransom

Photos and video by Keith Bedford

FERGUSON, Mo. — He sat in the front pew, listening as the pastor of Prince of Peace Missionary Baptist Church preached about the blessings bestowed on those with a humble spirit and audacious dreams.

“Obama had only been a senator for 768 days when God had put greatness in his spirit to aspire to the greatest office in the world,” said the Rev. Willie E. Kilpatrick, wiping the sweat from his brow as 17-year-old Waiel Turner and the congregation shouted in agreement. “He had a dream . . . ”

Turner has big dreams too: Graduate high school, go to the Air Force, retire as a colonel or general, and, in 2042, follow in Obama’s footsteps, becoming president of the United States. The teenager’s mama had always told him that if a black man raised by his grandparents could become president, then a black boy from Missouri could grow up and do the same.

But there is something else that he and his peers believe to be true: Black lives are not valued the same as others. That, he said, was evident more than two years ago when Michael Brown’s body lay bloodied and uncovered in the street some 7 miles from where Turner now worshiped and dreamed on a chilly Sunday afternoon.

As the nation’s first black president prepares to leave office, a generation of black teens stands on the cusp of adulthood, eyes wide open, trying to make sense of a world that many of the adults in their lives say they are struggling to understand. From the kitchen tables in Ferguson, to the high school hallways and street corners of Baltimore, to the historic neighborhoods of Boston, dozens of black teens, in interviews, questioned their place in America.

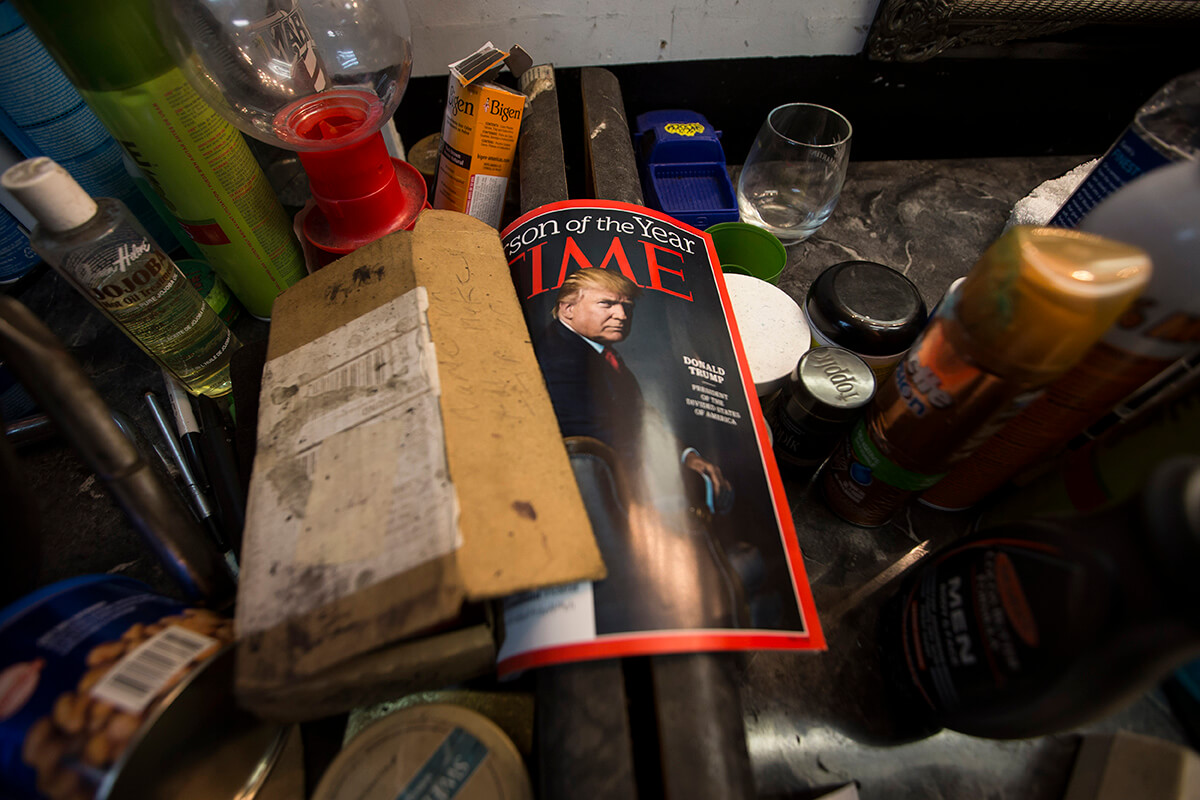

They live in a country that can elect — then reelect Obama — while enduring the savage run of police-involved shootings, causing inspiration and desperation to collide. It is this generation that will inherit the world that will be shaped by Donald Trump’s presidency, and they must find a way to live through it — and thrive.

For some, it’s a struggle. For others, the answer is clear cut. But on this much they agree: President Obama proved the impossible possible. Now, they will come to know another president, a man who many of them said ran a campaign with racist and xenophobic overtones.

Turner was too young to remember much of Obama’s first inauguration, but he remembers his second in 2012, saying it “was when I actually woke up.” There’s a possessiveness in the way Turner and his peers talk about Obama. He was — and ever will be — their president.

Donald Trump?

“He’s not my president,” Turner said. Trump is the imminent leader of the country, but there’s no bond, no connection to the man who will be the nation’s 45th president. Still, Turner said, he “can’t be a hater.” Trump won.

In 2008, Obama campaigned on a promise of hope and change. His victory prompted a national conversation about whether America was entering a “post-racial society” — with the implied hope that the country had at last atoned for one of its greatest original sins.

“Such a vision, however well-intended, was never realistic,” the 44th president said Tuesday night during his farewell address.

But as Obama fought a tough reelection battle, Trayvon Martin was shot to death in Florida. Then came Eric Garner. Michael Brown. Laquan McDonald. Tamir Rice. Eric Harris. Walter Scott. Freddie Gray. Paul O’Neal. Alton Sterling. Philando Castile. They represent a string of high-profile, police-involved deaths with varied circumstances and outcomes. But the pattern was numbing.

AdvertisementContinue reading below

At a time when prominent examples of black success abounded, young black men were still far too often being seen as a threat walking down the street. What did it mean? How did it happen?

Police officers in Ferguson fired tear gas at protesters demonstrating after Brown’s August 2014 death — and the country watched. And in April 2015, when Gray died after being handcuffed without a seat belt in a Baltimore police van, Maryland’s harbor city became the site of unrest when the fury over Gray’s death crescendoed. It’s the kind of racial animus Boston knew all too well from its own bitter struggles some 40 years ago — the wounds of which remain to this day.

“Before the Ferguson protest, nobody but us talked about racism,” Angela Davis, the noted activist and scholar on race, said during a Q&A with Princeton University professor Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor in Chicago. “Now, every time you turn on the radio or television, everybody is talking about racism.”

But has it helped?

Ferguson

As Ferguson burned and much of the world pondered the reasons why, Kayvion Calvert and his parents didn’t really talk about the events that were unfolding just 10 minutes from their home as crowds converged on West Florissant Avenue, a roadway lined with strip malls that could exist in anywhere USA. But Calvert and his family watched on the news as people marched along the thoroughfare, arms raised, shouting, “Hands up, don’t shoot!”

At the Prince of Peace Church, just outside Ferguson, leaders still remind them: “Don’t purposely draw attention to yourself.”

No sagging pants, hoodies, certain jeans and shoes, Afros, and dreadlocks.

“That’s the stereotype for a black, African-American male,” the 15-year-old said one recent Sunday evening while sitting on his bed, dishes done and homework next.

And while Obama’s election to the country’s highest office might have given Calvert the confidence to know that “outside of singing and acting I can do anything,” he said it didn’t inspire faith in government because of “how sketchy I think it is.”

“I really started to focus on politics with Barack Obama,” he said.

But, like many of his peers, he wasn’t jolted into awareness and action until Brown’s death.

He was going into eighth grade, attending classes in the same struggling school district as Brown, and students talked about it a lot. There were writing assignments and debates — both formal and impromptu — about Brown’s death and the aftermath. Some students protested by walking out of class, while others demanded better resources from the school system.

But did any of the protests — inside the school and on the streets — help?

“It was a good thing and a bad thing at the same time,” said 17-year-old Maryah Green, as she stood behind the counter of Natalie’s Cakes & More, a bakery that has recovered — and expanded — after being vandalized in the riots that followed a grand jury decision’s not to indict then-Officer Darren Wilson for fatally shooting Brown, who was struck at least six times.

Obviously, the protestors got the attention they needed, if not necessarily the results, “but we’re always referred to now in a negative term,” the lifelong Ferguson resident said.

While some of the buildings and pockmarked streets bear the scars from what happens when that tension boils over, other changes go beyond the community’s structure, to its psyche.

The atmosphere is changed, said 18-year-old Kevin Black. “The way people maneuver and get around is a whole lot different.”

People don’t walk as much, Black said, opting to ride the bus or get a ride, and they tend to be less likely to stand around stores — all of which he thinks is a good thing.

“It gives police less reason to investigate,” he said. “They had the right, if they see something suspicious, to investigate it, so that brings people out the way of the police.”

Black is a senior at Riverview Gardens High — in a school district that until recently had been stripped of its accreditation and drained of resources under the state’s controversial transfer law that forces the unaccredited school districts to pay for students’ transfers to higher performing schools if they choose.

Millions of teens had hoped Obama’s election would bolster schools like Black's, that the promise of change that so defined his 2008 campaign would be radical and swift. And then reality set in.

“Some schools can’t afford everything. Some schools can’t get the resources that they need to stay up. I thought that was going to change,” said 16-year-old Daveon Brown, Black’s schoolmate.

He thought Obama’s ascendancy to the White House would ease the deep mistrust between police and communities of color that existed long before Brown’s death.

“I thought that was going to change,” the sophomore said. “Things like that.”

But the realities of government bureaucracy quickly tamped expectation, and, in the end, one man can only do so much, even a president, especially, “if everybody in Congress doesn’t agree with what he wants to do,” he said. “So it was kind of: We thought one thing and what we thought, I don’t want to say it didn’t happen, but . . .”

“It’s happening differently than you thought it would happen,” classmate Keyon Moore interjected.

People expected too much from Obama, and when those expectations weren’t realized, the thought was “we’re all just failing,” Moore, 17, explained.

“Everyone depended on him to do everything, but really there were not a lot of people on his side,” he said. “So therefore, it’s not his fault. It’s the government’s fault.”

But, Black said, Obama did more than enough to fulfill his vow that transformation was soon to come, pointing to how the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare, reshaped the American health care system (Republicans are expected to repeal it under Trump). He also cited the president’s call to action to reform the criminal justice system, which included signing the Fair Sentencing Act that eliminated mandatory minimum sentences for possession of crack cocaine — a policy long viewed as racially discriminatory.

“I believe he could’ve done more if given more time,” said the high school senior with dreams of going into architecture. “My question to President Obama is: If you had more time, what do you think you could have accomplished?”

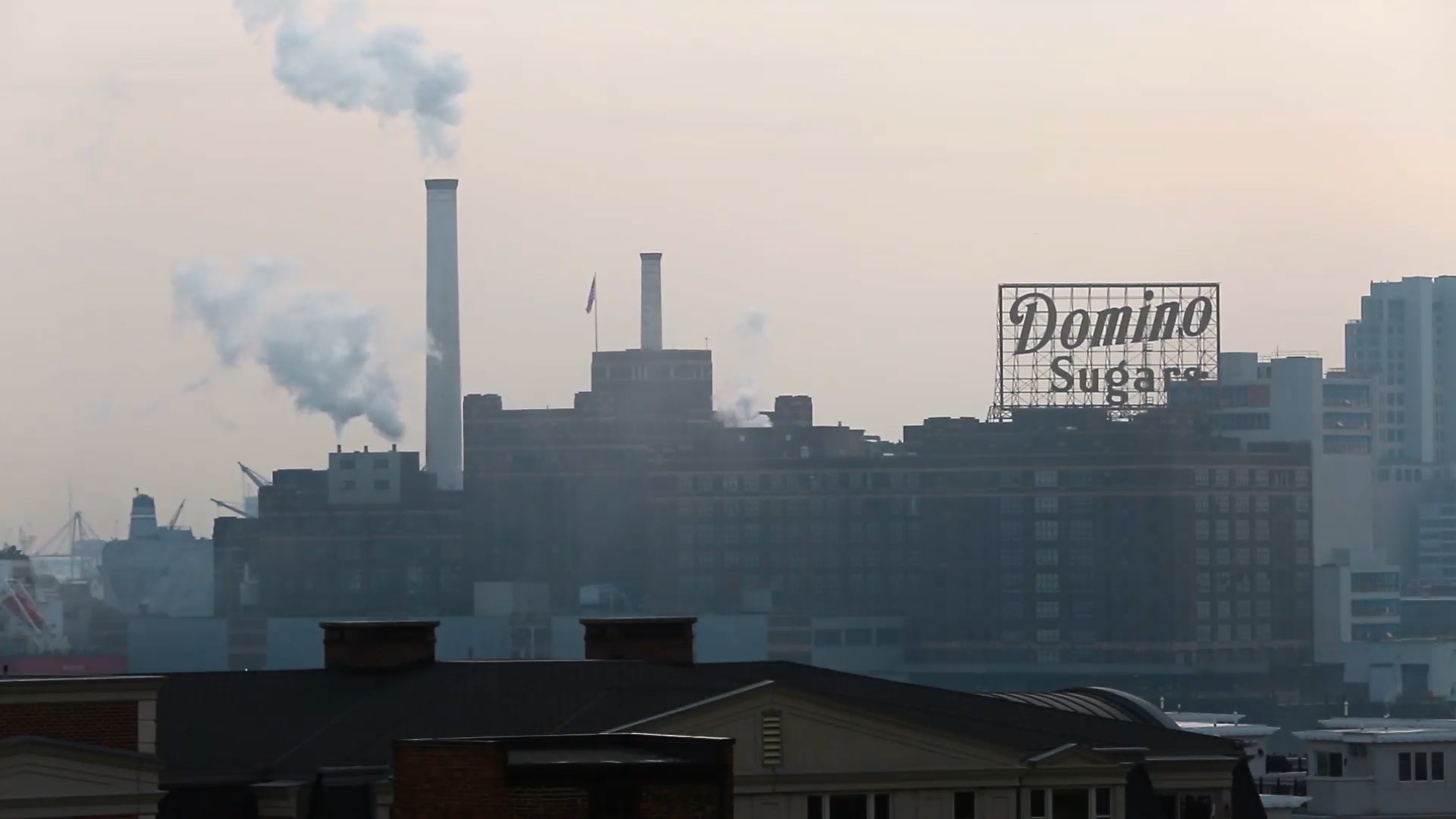

Baltimore

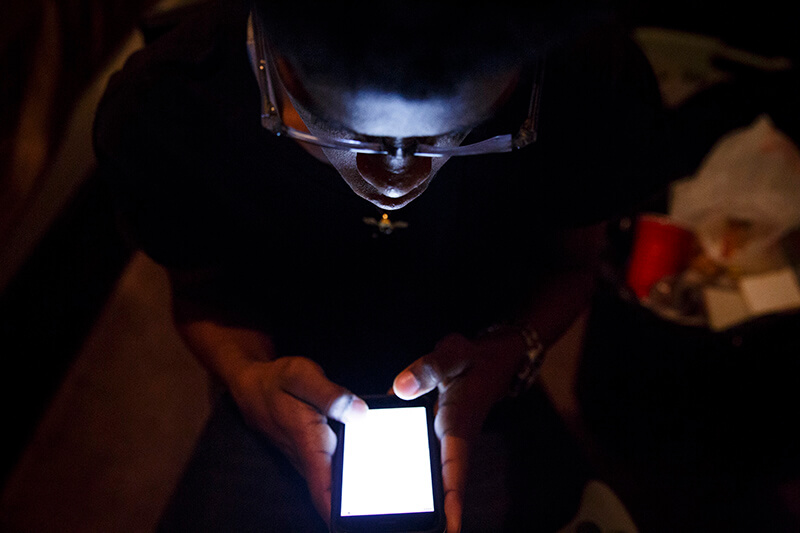

In Baltimore, 16-year old Rastehuti Missouri remembers watching the news — and his social media — at home as it showed the flames of a burning city illuminate night skies in Ferguson. Throngs of people stood before police in riot gear, clutching “nonlethal” rifles and wielding shields in defiance and protest. He remembers telling his mother: “That could never happen in Baltimore.”

Until it did.

Freddie Gray died, some seven months after Brown, suffering a spinal cord injury while in police custody.

Like Ferguson, Baltimore would be placed under a citywide curfew, and the disobedient were met with smoke bombs and pepper spray pellets. Scenes played out “like something out of a movie,” said 19-year-old Na’im Smith, whose high school in Northwest Baltimore, near Mondawmin Mall, was locked down.

A SWAT team rushed inside, he said, and escorted students out. A city bus took him away from the tension, but the drama followed him home. Eventually, a military Humvee parked at the end of his street. That’s when the seriousness of the situation began to set in.

Obama did not withhold his contempt for Baltimore’s rioters, calling them “criminals and thugs.” Smith said those words from “my president” upset him. His anger, however, was not necessarily directed at Obama but how people responded to his words.

“Let’s just be real. He’s not calling everybody hoodlums,” the high school senior said. “Let’s focus on the fact that we have these issues.”

For Rastehuti Missouri, the severity of the situation became all too real when the vacant buildings surrounding his family’s home began to burn, he said.

Still, he said, there was a point to the madness: to let people know how “crazy the city actually was.” People weren’t burning down buildings simply to cause mayhem, even if that’s what some adults think.

“They would consider what we did a riot, where I would consider it an uprising, showing we had a voice,” Missouri said. Police, he said, are “supposed to protect and serve.”

Smith said the problem stems from “a wide range of things . . . from [police] leadership on down to the specific officer and training . . . to funding.”

Some officers, he added, are just “bad tempered.”

Watching his city burn made him double down on his dream of becoming a police officer after graduation. He sees law enforcement as an act of service to his community — a ministry of sorts. Officers often interact with people at their lowest moments, and he sees the badge as an opportunity to bring encouragement and resources to those in need.

If enough young people with this mindset join the police academy, then “now all of a sudden there’s a shift in the way police officers handle themselves,” he said. “I get frustrated when I hear so many people talk about how they hate police. Well, if you’re well-abled, why not help change it?”

That’s not to say he doesn’t worry about putting on the uniform. But his anxieties don’t come from fear of retribution by his community, although he said friends often joke, “I’m a stop messing with you. You going to be the feds.”

No, he worries about the country’s next commander-in-chief.

There’s no trust there for Smith, who says Trump has no filter, expressing the first thing that comes to mind — often in 140 character bursts on Twitter. Could a flippant statement become an unofficial directive, unleashing civil unrest? What happens if that directive conflicts with Smith’s personal moral code, but he’s forced to follow through as an officer of the law?

“After he was elected, I began to get worried,” Smith said. Trump’s campaign tapped into something caustic, dividing the country in a way that he fears will cause our nation to turn on itself. “What is the world going to look like in the next four years?” he wonders.

If Trump is still in the White House four years from now, 13-year-old Jamal Karim said he’s going to “try my best to get him out of there” and make sure that people who know nothing about politics “don’t get to just walk up in here because they have money.”

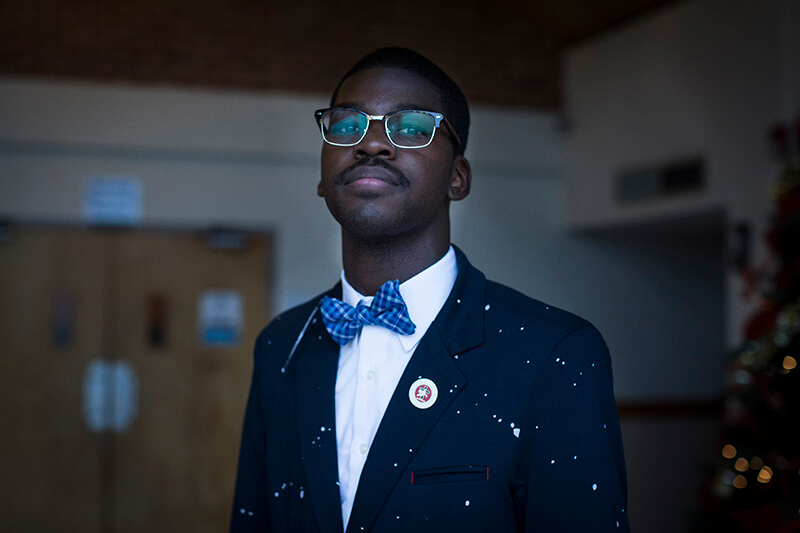

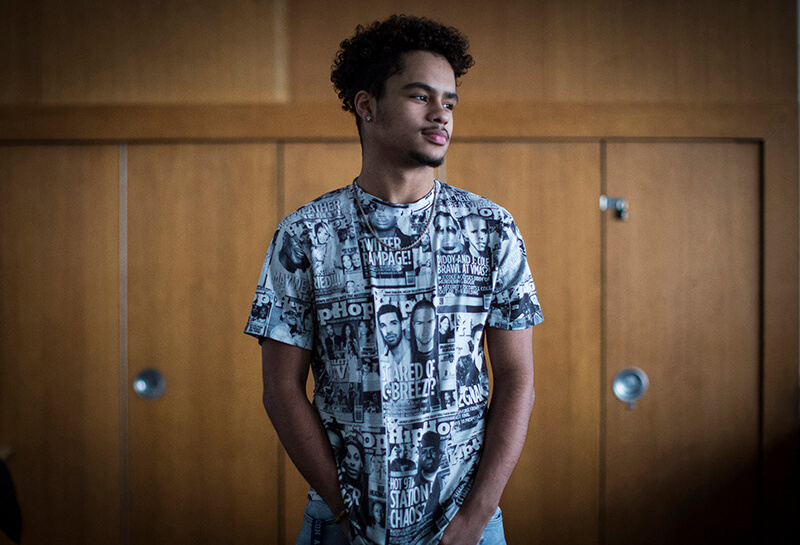

![“Every vote is important. My grandmother said she didn't vote, and I told her that her vote could've counted. [Hillary] Clinton could've won for all of that.”](assets/img/Bedford_161130_BALTIMORE_016.jpg)

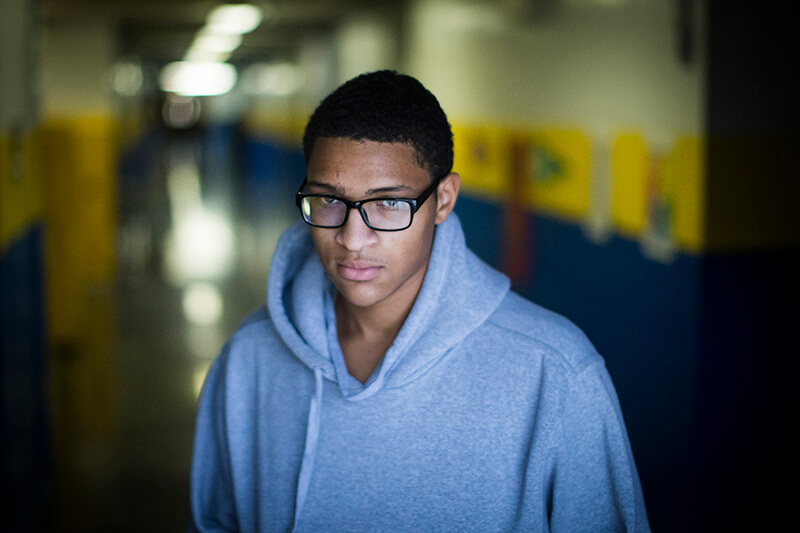

![“I love my city, but I hate how we’re living. It's not even just Baltimore. Other cities are going through [this] type of stuff now too. So black lives matter, that's why they be protesting. They feel that we should have freedom, that we should have peace.”](assets/img/Bedford_161130_BALTIMORE_019.jpg)

“Being president, that’s some serious stuff right there,” the middle school student said.

His Lakeland Elementary/Middle School classmates agree, fearing that the country is “getting ready to go back to the old ways” — the times before Obama, when they said black people were looked at as less than equal.

“They looked at us like we was some monkeys, like we wasn’t people,” Neviah Perkins, 13, said.

“Like we just had dirt on our skin,” interjected 13-year-old Jaziah Gilbert.

“Like we wasn’t nothing,” Perkins’s little brother, 12-year-old Ahmaree Perkins, concluded.

Neviah Perkins said Obama “made our race look . . . beautiful.” No one had ever seen a black man sitting in the White House, calling the shots, “and that scared them,” she said.

They aren’t quite as convinced as Karim that they have the power to continue Obama’s momentum and slow Trump’s tide, but the feisty eighth-grader, who has yet to hit his teenage growth spurt, persists. More young people need to speak out to get people’s attention, he said.

“If we got their attention before, [we] wouldn’t be in this situation. He wouldn’t be president,” he urged. “We can still get our voice heard. We can get to the right people. I’m being serious.”

Boston

Boston has been there before, grabbing international headlines because of racial unrest. The battle to integrate the school system in the 1970s left the city so bruised and battered that racially motivated incidents and harassment were once seen as the norm in some neighborhoods.

And while the city has escaped the unrest that roiled Ferguson, Baltimore, and other major US cities, teens here felt the chaos and despair all the same.

Eighteen-year-old Joseph Okafor said the fatal shooting of Brown and others after him was a wake-up call for black Americans that “just because one of us is the figurehead of this system does not mean it’s necessarily going to change.”

The profound sense of hopelessness that followed Brown’s death is just as much etched into his memory as the day Obama became the nation’s first black president. Okafor’s Hyde Park home, which was a place of such joy when Obama won in 2008, became a place of sorrow as he sat on the sofa with his then-11-year-old brother, monitoring the outrage in Ferguson on Facebook.

Bereft, he remembers thinking: “That could be me or my little brother.”

And so on Election Day last year, he did what he could to help change the world he lives in — he went to the polls, and he voted for Hillary Clinton.

AdvertisementContinue reading below

Andre Robinson isn’t old enough to vote, but the 15-year-old Dorchester resident has no plans of sitting on the sidelines and waiting. The budding activist feels a responsibility to play a role in easing the mistrust that so often stunts a constructive relationship between police and communities of color. Robinson meets face-to-face with officers through a community program, discussing their relationship with minority communities and the recent shootings of black men.

Robinson recalled one officer saying: “Things like this are happening because no one understands each other anymore and no one takes the time to understand.”

But for 17-year-old Rasheem Muhammad, it’s simple: “If you’re born black, you know what bias is.” It’s something the teenager has addressed in his poetry:

“...If you think that our struggle has gone away

that is a deadly illusion to which you have fallen prey...”

Muhammad lived in Dorchester until he was 9, and he went to a school where he said most of the students looked like him. He never noticed how segregated his life was until his mother’s sickle cell disease worsened, and he left the city to live with an uncle in Whitman, a small, mostly white suburban community in Plymouth County.

He said he could count on one hand the number of black students at his school there. He was treated differently and began to feel his blackness. Some white classmates used phrases like, “Yo, what’s up bro, you my dawg, and you’re my homie,” when they talked to him. A white friend of his mother’s friend, who was caring for Muhammad while his mother was in the hospital, took to calling him “Blacky.”

“I kept on continuously being reminded I was different,” said Muhammad, whose mother died in 2014. The year Obama won, Muhammad’s mother told him anything was possible. He never forgot that.

Reflecting on this year’s election, Muhammad, who returned to Boston to live with his aunt in 2015, said: “Struggle is a part of life. Who has time to stress about a bunch of white politicians?”

Steven Jackson said he and his friends are just trying to survive. The 17-year-old from Mattapan worries that his reality of being seen as a threat will not change.

Over the summer, the teen and several friends were stopped by police in downtown Boston, where they said officers asked if they could speak with the young men because “you guys look suspicious,” Jackson recounted. He’s had high-beam lights flashed from a police cruiser into his face as he walked with a friend. And he and friends have been pulled over and accused of being “loud and rowdy.”

“Being a young black man in America today puts fear into our hearts,” Jackson said. “We’re targeted as monsters and villains when the truth is we’re just the same as any other person in this world.”

But Jackson, an honor roll student and athlete, says his education places him closer to his goal each day.

“The opportunities for me, the doors for me are never closed as long as I keep going, keep pushing,” he said.

He finds hope, he says, for a better future because of Barack Obama, a black man who defied the odds.