Under Siege: Democracy’s front lines in crisis

AMERICA’SELECTION WORKERSARE LEAVINGIN DROVES..

CENTRAL LAKE, Mich. — Judith Kosloski used to like her job.

The no-nonsense clerk of this small township, tucked amid the lakes of Northern Michigan, enjoyed matching faces with names as she kept her local government humming. Processing her community’s tiny payroll, deeding its cemetery plots, running its elections. At 77, the spiky-haired Kosloski said her job is nothing less than to be Central Lake’s “guiding light.”

But after the 2020 election, the job lost its glow. Her vital municipal role has turned hellish.

A tabulation error by the Antrim County clerk — making it appear momentarily that Joe Biden had carried the deep red county — sparked a feeding frenzy among Donald Trump supporters and led to an hyperbolic lawsuit alleging fraud. On the day after Thanksgiving 2020, a lawyer who claimed connections to Trump visited with investigators and others, seeking access to her tabulator, a machine that tallies up votes.

And there was more, she said: threatening phone calls, the letter in her home mailbox asking if she was proud of herself for causing the whole mess, the thoroughly-debunked report from the investigators that cited extra complications in Central Lake as a supposed smoking gun. The endless second-guessing that followed.

“There are days that I go home and just sit and cry,” Kosloski said from behind her desk last month, where a stack of pale green election paperwork was piled up next to her. “I’m done.”

When Kosloski’s term ends in 2024, she is going to retire, driven out sooner than she once planned by the tide of suspicion, threats, and harassment that former president Donald Trump’s ongoing promotion of election conspiracy theories has unleashed across the country.

“I think a lot of clerks are doing the same thing,” Kosloski said. “We’ve had it.”

She’s right.

Kosloski’s impending retirement is part of an exodus of election workers since the 2020 election, depleting the anonymous corps of clerks and officials who make it possible for Americans to exercise their most basic right.

Experts worry that the loss of these foot soldiers of democracy drains the system of experience and institutional knowledge at the very moment election deniers are looking to seize on any actual or alleged mistake to further erode public faith in elections.

“It leaves a vacuum at best. At worst, (the departing employee) gets replaced by an election denier,” said David Becker, the executive director and founder of the Center for Election Innovation and Research.

A Globe review of the ranks of top county election officials in five hard-fought battleground states — Arizona, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Georgia — found a dramatic jump in election official turnover. A similar trend held for the municipal election officials of Massachusetts, which of course is no battleground. Between the 2016 election and the 2018 midterms, the six states saw about 18 percent of those top officials depart. In the nearly two years since the 2020 election, that figure has risen to roughly 30 percent. These figures do not include turnover in the lower ranks of election administration, which could be even higher.

The pattern is by no means limited to battleground states. In South Carolina, just four out of 46 county election directors left their jobs in the two years after the 2016 election, the Globe found, compared to 19 counties that have seen vacancies in those roles since 2020, state figures show. In Utah, 17 out of 29 county clerks who administered the 2020 election have either quit or plan to leave at the end of their terms, according to state figures; the Globe could find only one who left within two years of the 2016 election.

Election worker turnover is increasing

The Boston Globe collected turnover data for top county election officials in five battleground states — Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin — along with four others, as well as analyzed a database maintained over time by the nonprofit US Vote Foundation. In eight of the nine states, significantly more of those workers have left their jobs since the 2020 election than departed over a similar period after the 2016 election.

Click on a state to see how the turnover rate changed from the periods between 2016 to 2018 and 2020 to 2022.

2020-2022 turnover rate

There are thousands of election administrators across this country and no central authority that tracks how many leave their jobs or why. But, to get a rough sense of turnover across the nation, The Boston Globe analyzed a database of election workers maintained by the nonprofit US Vote Foundation. In nearly every state that the group reliably tracks, more of those workers appear to have left their jobs since the 2020 election than departed over a similar period after the 2016 election.

Clerks’ reasons for departures are manifold. Some are simply retiring. Some departing clerks have cited the harassment as enough by itself, while others say constant queries from distrustful voters, coupled with onerous new voting laws, are making their often relatively low-paying jobs harder to stomach.

“I can see in their face, they’re worn out,” said Michael Adams, the Republican secretary of state of Kentucky.

The Globe interviewed 73 current and recently departed election officials across 18 states, who painted a picture of an apolitical, largely obscure profession facing an unprecedented crisis, beset by activists who believe that the 2020 election was rigged.

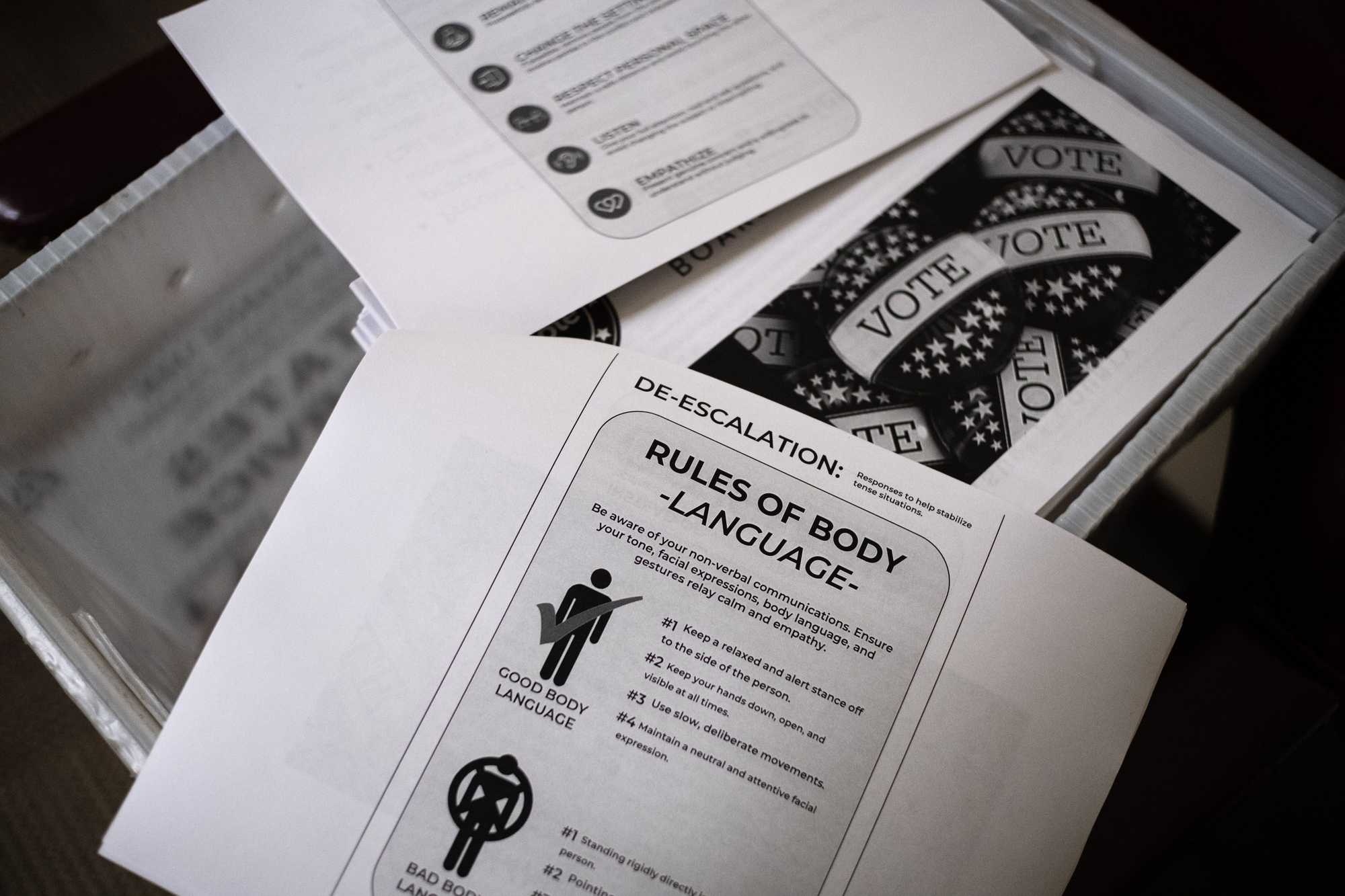

Almost two years after Trump’s defeat, election deniers are still pursuing three lines of attack on their profession: challenging and harassing workers directly, making endless demands for records and recounts that leave them overburdened, and pressuring Republican local elected officials and law enforcement to join their cause.

Election officials say the deniers seem driven by a conviction that persists without evidence and goes beyond politics. “It’s more religion,” said Samuel Gedman, the chief deputy clerk in Grand Traverse County, Mich.

At their service counters, their board meetings, and even family gatherings, they find themselves with the all but impossible task of proving that something outlandish did not happen. And, across the country, they know that a single error — like the one in Antrim County — can put them in the crosshairs of the election deniers.

“All it takes is one mess-up from me, and I just pray every day, no, not today,” said Aubrey Rowlatt, the clerk-recorder for Carson City, Nev., who has opted not to run for reelection. “I’ve never felt as uneasy about an election as I do this one.”

And they worry that deniers’ hunt for mistakes, which sucks up hours of administrators’ time as they produce public records and answer suspicious questions, is wearing them down, making them more prone to error.

Today, some of the administrators feeling the most stress work in places where Trump won overwhelmingly, and many are Republicans themselves. In Surry County, N.C., Trump received three-quarters of the vote, but that didn’t stop an election denier this year from alleging that the county’s voting machines had been in communication with Russia in 2020. And while such accusations are the stuff of fantasy, they land with force in the lives of the professionals who are targeted.

“We thought we’d been through everything we could go through in 2020,” said Michella Huff, the director of the Board of Elections in Surry County. “But we had no idea the different types of things we would be going through in 2022.”

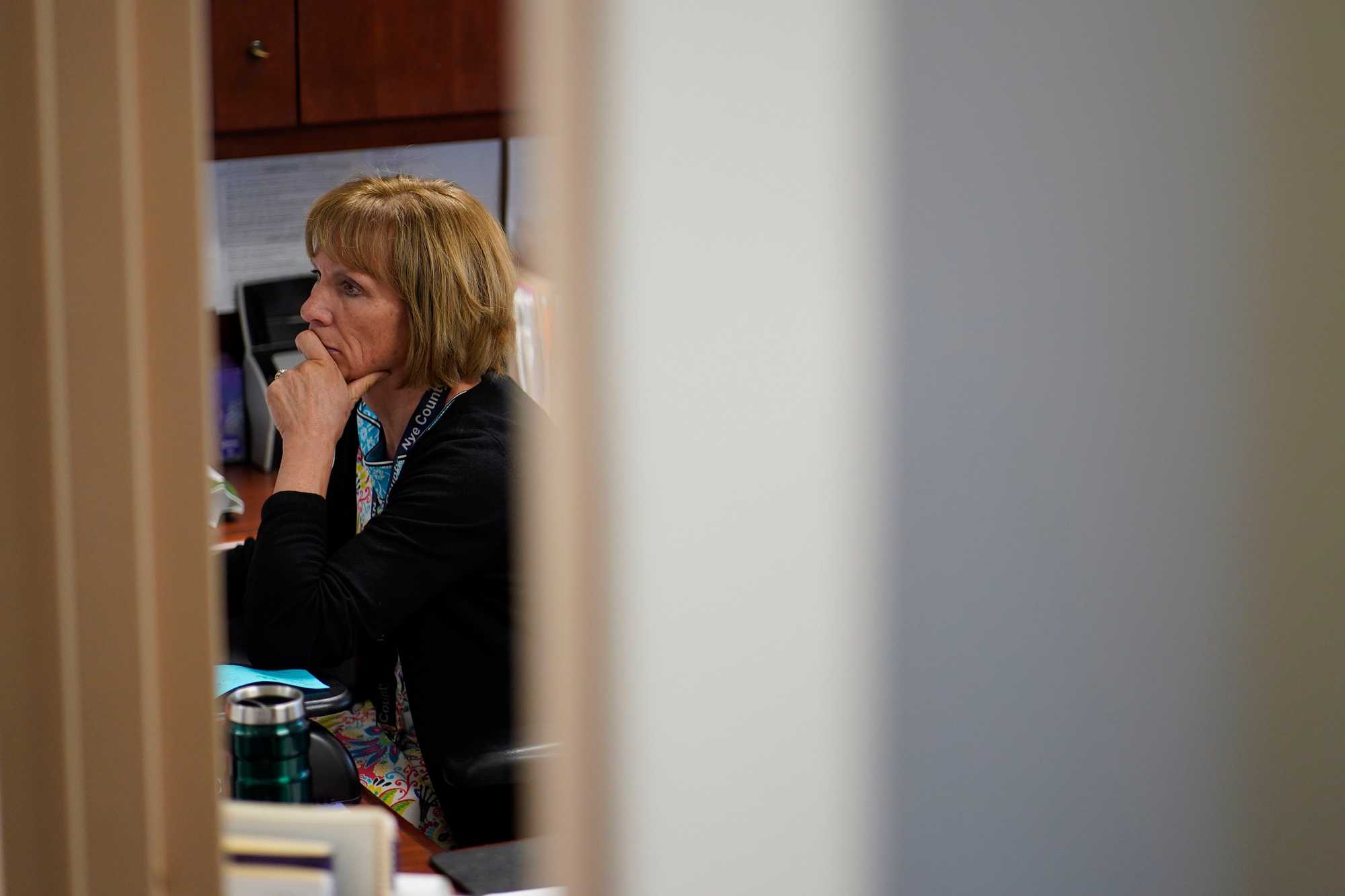

In another Trump-dominated county, Sandra Merlino retired in August in the middle of her term as county clerk in Nye County, Nev., after her commissioners gave in to the demands of an election-denying activist who insisted voter fraud was behind his loss in a 2020 congressional race. Over Merlino’s strenuous protest, they called for the county’s ballots to be counted by hand.

“It was horrible, because I’ve been doing elections since January of 2000,” said Merlino, who was immediately replaced by a clerk who has falsely said Trump won the election. The activist that pushed for the hand count, Jim Marchant, is now the Republican nominee for secretary of state and leading in the polls.

Advertisement

Not so long ago, most voters would have been hard-pressed to name the people who administered their elections, let alone seek them out. Today, stories of the harassment of election workers are as disturbing as they are plentiful. In Weber County, Utah, the county clerk and auditor’s car was vandalized three times outside his home — a smashed tail light, a broken window, and an egging — all around key, election-related dates in 2020 and 2021.

“I get e-mails all the time: ‘We’re watching you, we know you’re in on it,’” said the clerk, Ricky Hatch. “My wife wants me to wear a bulletproof vest to work.”

In Pinal County, Ariz., in 2020, a rock sailed through the glass door of the elections office, according to the former elections director there, Michele Forney, who never knew who did it or why. Since the 2020 election, so many threatening calls have poured into that state’s secretary of state’s office they have taken the phones offline twice.

In Michigan, Tina Barton, the former clerk in Rochester Hills, north of Detroit, received sexualized, profane phone and Facebook messages after the election. “I deserved a knife to my throat ... I deserved to be executed,” she said, recounting a few of the messages.

The authors of this sort of vicious harassment rarely face consequences. Numerous election officials interviewed for this story described an indifferent response when they alerted law enforcement about the threats and abuse they were receiving.

Richard Barron, the former elections director in Fulton County, Ga., said he went to the police when he and members of his staff, including Shaye Moss, who offered harrowing testimony in front of the Jan. 6 committee this summer, were deluged with death threats after Trump himself baselessly scapegoated them in late 2020. But he got only disappointment for his trouble.

“They were being harassed horribly,” he said but he recalled that the county police said they couldn’t protect the women because they lived in different counties. “The Fulton County police didn’t do anything.” Moss and Barron have both left their jobs.

Hear from election workers

The Globe interviewed dozens of current and recently departed election officials. Here’s what they had to say about what it’s like to run elections in the wake of 2020.

And while the Justice Department has devoted a task force to abuses against election workers, it has only charged four new cases as of August. The reason, officials say, is because many hostile contacts did not necessarily contain a “threat of unlawful violence” — a legal distinction that often leaves election workers feeling like they’re on their own.

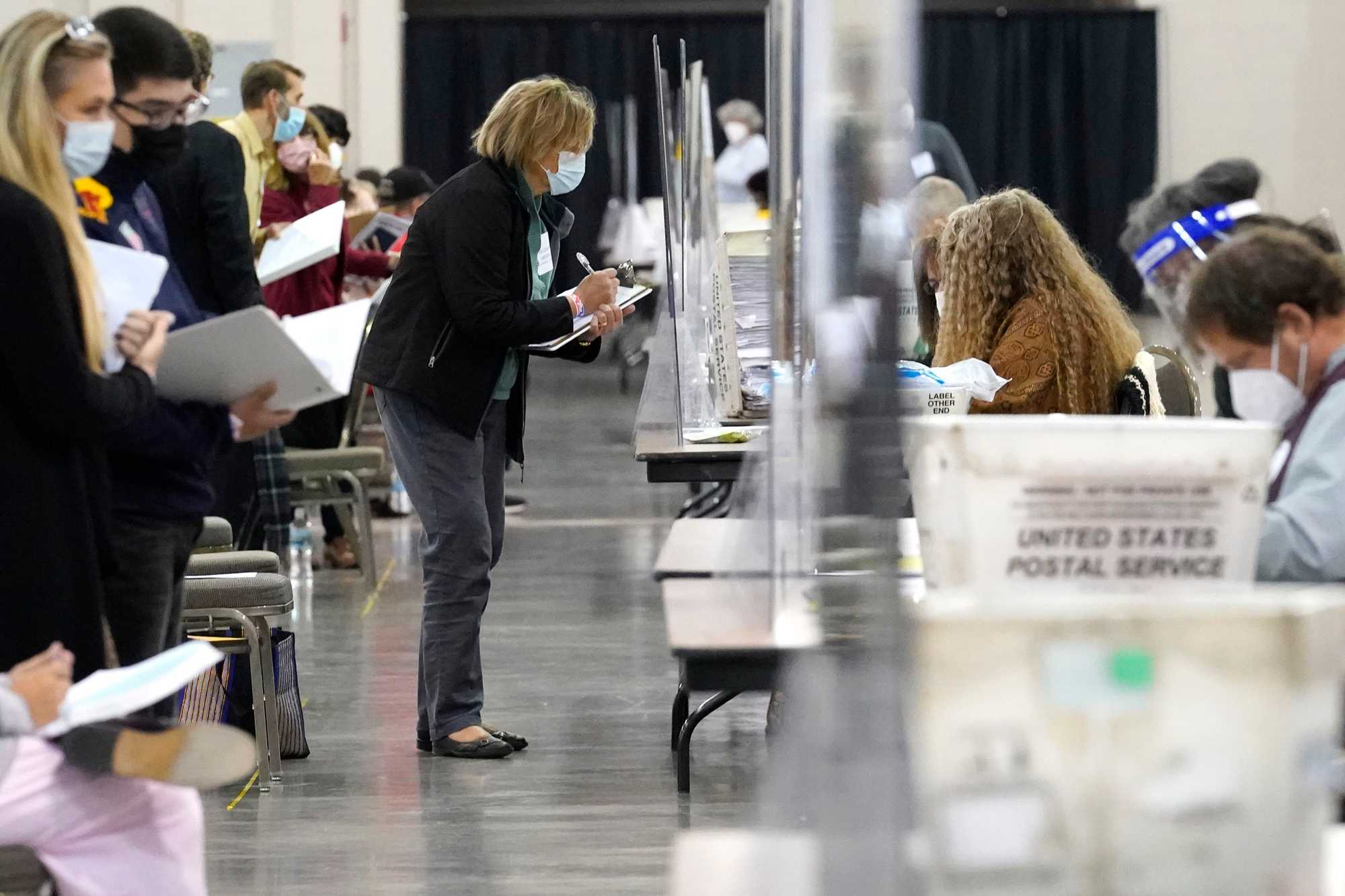

Beyond the threats, the suspicious questions from people newly conditioned to distrust the system don’t stop. Many election administrators have grown increasingly concerned about the way Trump activists such as the MyPillow CEO, Mike Lindell, and the election-denying lawyer Cleta Mitchell have weaponized legal processes, urging their followers to sign up as election observers, file rafts of public records requests, demand recounts even when the margins were large, and mount groundless challenges to the voter rolls.

“I’ve had 21 (records requests) since Monday morning,” sighed Tonya Wichman, the director of the board of elections in Defiance County, Ohio, on a Wednesday in August.

Such records requests must by law be responded to. But the sheer numbers now make that duty feel like another form of harassment.

“That’s abuse of process, it’s a different form of abuse than nasty e-mails, but it also puts a great strain on these poor people,” said Adams, the Kentucky secretary of state.

Many election officials say they are already fighting hostility from local Republican elected officials, and the political environment is only getting more inhospitable, as election deniers climb the ranks of the GOP. The election-analyzing website FiveThirtyEight estimates that 60 percent of US voters this fall will find at least one election denier on the November ballot. Their campaign rhetoric already promotes distrust of election administrators; soon, they could also be making the rules.

Advertisement

About 10 minutes away from Judith Kosloski’s office is the office of the Antrim County clerk, Sheryl Guy, who keeps a current directory of the 83 Michigan county clerks on her desk, one for each page. It is stuffed with the yellow sticky notes she uses to mark her colleagues’ departures, sometimes with notes about when they left. “Last day, 8/27/21.” “Retired, 7/22.”

“What do you think these people are leaving for?” she asked. “It’s either the crazies in the public or the politics inside the building.”

Guy knows a lot about both. In the hours after the polls closed in 2020, her county became ground zero for conspiracy theories that went all the way up to the Trump White House.

It is hard to imagine her office as a command center for election fraud — huge stuffed minions from the animated comedy franchise sit on a high shelf keeping watch over a room decorated with a faded Norman Rockwell print on the wall and meticulously tended succulent plants. But Guy’s operation became a prime target for wild allegations and hostility.

“Take 2020, put it in a little box, and bury it,” said the chief deputy clerk, Connie Wing, who was looking at sample ballots for the midterms, trying to focus on the next election. “It’s like, that hand keeps coming up through the ground.”

Shortly before the 2020 election, Guy, a cheerful Republican, made what seemed like a small, if embarrassing, mistake: She failed to properly update her election software after ballots in a couple of local elections got corrected. As a result, on election night, votes got assigned to the wrong candidates and it briefly looked like Joe Biden had won this deep red county.

“We were just dying,” Guy said.

As she and her team worked to fix the problem — Trump won the county with more than 60 percent of the vote — the phones began to ring.

“Threatening calls, stupid calls, telling us how ignorant and dumb we are, how we should be put in front of a firing squad,” Guy remembered.

A local real estate agent, Bill Bailey, a denier who lives in Kosloski’s township, sued the county. Election-denying lawyers descended, first pushing for access to local clerks’ tabulators, including Kosloski’s. In early December, a judge paved the way for an examination of all of the county’s election equipment.

The resulting report, written by an organization called the Allied Security Operations Group, alleged that the county’s Dominion voting machines were “purposefully designed with inherent errors to create systemic fraud,” a conclusion a state investigator would describe as based on “false, inaccurate, or unsubstantiated statements.” But it caught the attention of Trump himself. An aide of his forwarded it to Jeffrey Rosen, then the deputy US attorney general, with the subject line, “From POTUS.”

For Guy, the stress was unbearable — her small mistake had become fodder for something much bigger than her office. As 2021 wore on, deniers staged two demonstrations outside her office: a prayer vigil, and then a rally. Then a conservative radio host piled on with his own lawsuit.

“Some days,” she said, “you just feel like you’re going to break.”

Adding insult to injury, she said, some members of her board of commissioners seemed to side with the election deniers, whose power in this state’s GOP is only growing. A former poll worker who baselessly alleged election fraud is now the GOP nominee for secretary of state, while the nominee for attorney general, Matthew DePerno, is the lawyer who represented Bailey in his lawsuit.

In the end, the lawsuits, now dismissed, the investigations, and a hand recount made almost no change in the 2020 voting, once the error was fixed. The final audit gave Trump 9,759 votes to Biden’s 5,959 in Antrim County. And a March 2021 report commissioned by the secretary of state and the attorney general rejected allegations of systemic fraud, chalking the problem up to human errors.

But all the overwrought machinations took their toll.

Guy is retiring at the end of her term, a decision she insists she made before the 2020 election. Wing, her deputy, has the qualifications to replace her, but she has decided to leave, too.

“I see what she goes through,” Wing said. “You couldn’t pay me to put up with what she’s put up with.”

Advertisement

Michella Huff once thought she was safe from the wave of election denialism that washed over so many other election officials. After all, the elections director of Surry County, N.C., had presided over a 2020 presidential election in which Trump won 75.3 percent of the vote and said things were fairly quiet in the immediate wake of the election. But her past six months are a study in the way determined election deniers are upending the lives of election officials, long after the 2020 ballots were cast.

On a rainy Tuesday in September in this rural stretch along the Virginia border, a pile of signs lay near a back entrance of the squat county service center bearing a stark message: “The people’s trust is shattered. We demand a forensic audit.”

The signs, which had been posted on the building’s property by the vice chair of the local Republican Party, Keith Senter, and taken down by Huff, were a reminder of the suspicion that suddenly descended this year — on March 28, to be exact.

That day, Senter showed up at Huff’s office with Douglas Frank, a math teacher from Ohio who is a close ally of Lindell, who has toured the country spreading outlandish election disinformation.

Huff said the men claimed they had proof that her voting machines had pinged cell towers in Russia in 2020, and that they needed to access her machines so they could examine their modems.

“Our machines don’t have modems,” so they can’t “ping” anyone, Huff told them, and resisted their demands to access her equipment for more than an hour. “They said they would see that I was fired if I did not comply.”

The deniers kept coming back. In April, Senter returned to Huff’s office and said he could not wait to watch her downfall. A local teacher began knocking on doors, looking for voting irregularities. Then came the May presentation to the Board of Commissioners, which was joined by Mark Cook, an “IT specialist” who has traveled the country falsely alleging that voting machines are easily hacked, and David Clements, a fired professor who has hawked his baseless claims of election fraud all over the nation.

“In Antrim County, there were 7,000 votes that were flipped in favor of Biden — that happened,” said Clements, using debunked disinformation to make his point. “We’re talking about real vulnerabilities that were exploited in the 2020 election.”

The deniers, Huff said, urged the board to cut her pay to $12 per hour. And as Lindell’s acolytes have marched through town, the number of hostile calls echoing their disinformation have ticked up.

“The deniers are definitely growing in numbers,” Huff said.

Senter did not return multiple messages seeking comment.

In late summer, Huff faced another scourge from the election deniers: a flurry of onerous public records requests.

Every single election office contacted by the Globe for this story said it had received mountains of such requests.

In September, Robbin Wagoner, a brand new clerical worker in Huff’s office, was still scanning tabulator tape to complete a public records request filed by Senter. The tape, which looks like an extra-long receipt, curled onto the floor as she scanned it into the copier, 10 inches at a time.

Nearby, a chalkboard read “63 days until general election.” It was a reminder of how much more there was to do while Wagoner was stuck scanning.

“I have to wonder, is it meant to distract? Is it meant to jeopardize?” Huff wondered. “I’m not quite sure what there is to find.”

Huff said the hostility has exacted a personal toll, with her withdrawing from aspects of normal life.

“I do more and more online shopping, so I don’t have to see anybody,” she said. “For a big part of the primary, I didn’t go to church. I didn’t want to hear it. I didn’t want to hear the comments.”

She adores her staff, and she wants to stay in her job, but sometimes she wonders if she can endure it all through the 2024 election.

“If it’s here,” she said, of the hostility and false claims, “it can happen anywhere.”

Advertisement

The day after Labor Day, Gedman, the deputy clerk in Grand Traverse County, Mich., received an e-mailed invitation to a meeting in his office building that promised to be a “rewarding, educational experience.”

The meeting, according to another flyer he received, was an “evidence and legal action meeting,” in which an activist hawking the findings of a Michigan group called the Election Integrity Force would review the “fraudulent election process” of 2020 and discuss efforts to decertify the county’s election result. Gedman was trying to get ballots ready for the November election, but he decided to go and listen.

“They were trying to recruit sheriffs, they were trying to recruit local clerks to turn over tabulators,” Gedman said. “They’re just trying to kind of, co-opt people who are already working in elections to sort of, validate this kind of thing.”

The Grand Traverse sheriff has not found these efforts compelling, Gedman said, but the activists found a more receptive audience a week earlier in Leelanau County, about half an hour northwest.

They spoke to a crowd of about 35 people, including several county commissioners and Sheriff Mike Borkovich, according to the Leelanau Enterprise, which had a reporter in the room. The speaker, a drywaller named Scott Aughney, made unsubstantiated claims about supposed discrepancies in voting records and likened state election officials’ tactics to those of Hitler and Stalin.

“Sheriff Borkovich audibly cheered Aughney when Aughney explained that he was devoted to exposing voter fraud throughout Michigan mainly because his faith in Jesus Christ was leading him to do so,” the paper reported.

In that county, Clerk Michelle Crocker endured so much hostility after the election that she started to feel unnerved at home, and started mixing up the vehicles she took to work. Yet she has had little support from her fellow Republicans on her county board as deniers have pressed their case.

“It’s not that they were slamming me, it’s just that my fellow Republicans were not stepping up to the plate,” Crocker said. “It would have been nice, because they were all on the ballot in 2020 and they all won.”

Crocker isn’t sure if she will run for another term or retire like Guy, joining the exodus of experienced election workers across the country. Neither is Bonnie Scheele, the county clerk in Grand Traverse who works with Gedman. One of her biggest critics owns an ice cream store, and she wonders what would happen if she marched inside and accused him, without evidence, of using dirty equipment. What if she could treat the public the way they treat her? What if she doesn’t come back?

“It’d be a real shame to let people drive you off of it, because it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy at that point,” Gedman said to Scheele during a Globe interview.

The deniers say “‘there’s something wrong with elections,’ and then they drive all experienced people, competent people out of it. And then there will be something wrong with elections. You can’t allow that to happen.”

Sarah Ryley, Tal Kopan, Jim Puzzanghera, and Lissandra Villa Huerta of the Globe staff and Globe correspondent Shannon Coan contributed to this report.

Credits

- Reporters: Jess Bidgood, Jim Puzzanghera, Tal Kopan

- Editors: Scott Allen, Mark Morrow, Jen Peter

- Multimedia editor: Christina Prignano

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development and graphics: Daigo Fujiwara

- Photo editors: William Greene and Kim Chapin

- Audio editors: Scott Helman and Jesse Remedios

- Copy editors: Mary Creane and Michael J. Bailey

- Data analysis: Shannon Coan and Sarah Ryley

- Audience engagement: Lauren Booker

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

© 2022 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC