At 5:54 a.m. on Nov. 8, 2000, CNN’s top anchors signed off after more than 13 straight hours of election coverage that had seen multiple incorrect calls on the winner of the presidency. “Folks,” political analyst Jeff Greenfield quipped, “in the year 2004, please, could you make up your minds a little more conclusively? Because I think we can’t take another election like this one.”

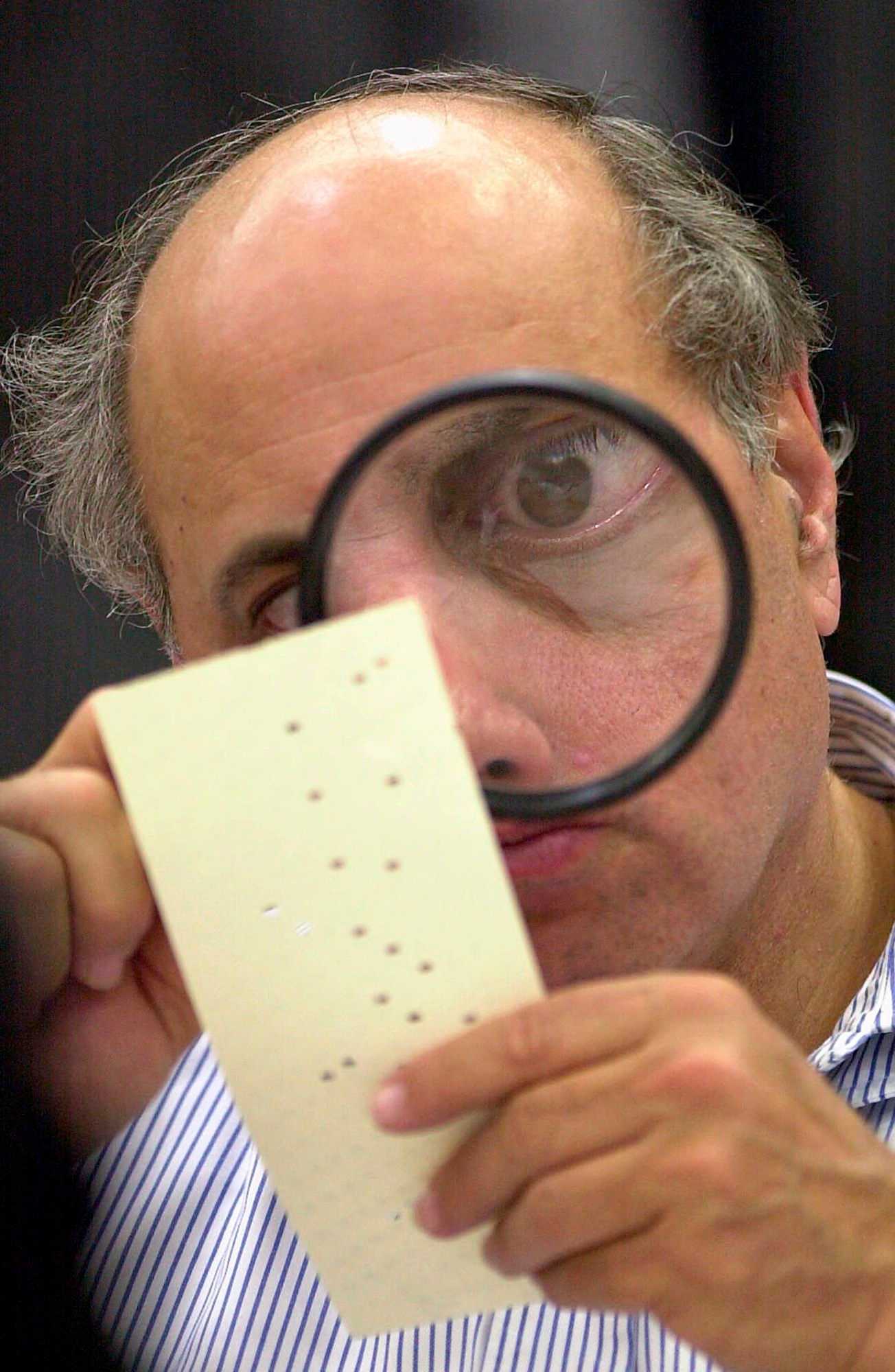

What followed was a crisis that tested the US election system like little had before. The parties warred bitterly over ambiguous ballots in Florida and vote-counting rules. The race for the presidency ultimately came down to fewer than 600 votes and was decided by the US Supreme Court in a deeply controversial ruling that made George W. Bush president.

It was a post-election season like none in modern memory, one that only ended peaceably when the Democratic candidate, Al Gore, bowed to the court’s conclusion and conceded.

Twenty years later, the furor of 2000 looks almost quaint. And Greenfield’s crack about our electoral system reaching its breaking point now seems prophetic.

In the 2020 presidential election, the problem wasn’t with the vote itself, which was remarkably accurate and well-run, especially amid a global pandemic. It was with the candidate who lost, but would not concede. The election crisis this time was fueled by then-president Trump and his supporters who spread conspiracy theories about the integrity of states’ elections systems and bogus claims that the outcome was a fraud that stole victory, and the White House, from Trump.

All this has added massive stress on a system that — while improved by bipartisan legislation and new funding after the 2000 debacle — has been left threadbare and struggling as the midterm election nears.

Unlike after 2000, there is little chance now of both parties agreeing on major reforms — or on much of anything. The American democratic system — which relies entirely on the competency and tirelessness of thousands of local election officials — is facing a test it may not pass.

“Elections have to have an end, results have to be final,” said Natalie Adona, the current assistant clerk-recorder and clerk-recorder-elect in Nevada County, Calif., who faced threats and harassment from election deniers in her job earlier this year. “If they aren’t, then democracy cannot function.”

“If conflicts are never resolved,” she continued, “I think it can only lead to violence. Don’t you?”

Advertisement

The effects of the current crisis have been measurable, especially at ground level. In highly contested battleground states, roughly 1 in 3 of the top election administrators has left the job after the 2020 election, far more than the last presidential cycle, a Globe review found. In fact, nearly every state saw more election officials leave after 2020 than departed after 2016, some at rates over 40 percent.

But what’s received less attention is the strain being heaped on a system that wasn’t healthy to begin with.

In interviews with 19 current or just-departed election officials across 11 states, a clear picture emerges of beleaguered civil servants dealing with everything from supply chain woes, to unfunded new requirements that exhaust their budgets, to cramped and outdated offices not designed to handle all-mail elections or dramatically increased scrutiny by partisan and sometimes disruptive election observers.

Local control is a central feature of the US election system, making it virtually impossible for a nefarious actor to disrupt or manipulate results on a large or nationwide scale. But the decentralization is also a bug, with more than 10,000 different jurisdictions managing elections, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

That leaves most election budgets up to cities and counties that are already struggling to pay for services like policing and infrastructure. Elections are often perceived as a part-time responsibility, even though planning is a year-round job. A handful of places, often major cities, are well-resourced. But many cities and counties have no wiggle room to handle extra expenses. Some barely stay afloat.

As a result, election workers have long been expected to perform miracles every cycle, stretching their meager budgets to keep up with the demands of voters and state legislatures.

“You’re throwing a party and you don’t know how many people are showing up … and you want to make sure everybody has a piece of cake,” said Jennifer Morrell, a former elections official who now works with the consultancy The Elections Group. “Even in the best of circumstances, running an election is a lot of work.”

And few election directors work in the best of circumstances.

Staffing is often a challenge, both for the day-to-day administration and Election Day itself. Election offices are frequently crammed into small parts of local government buildings that hardly have room for ballots or observers or that lack security.

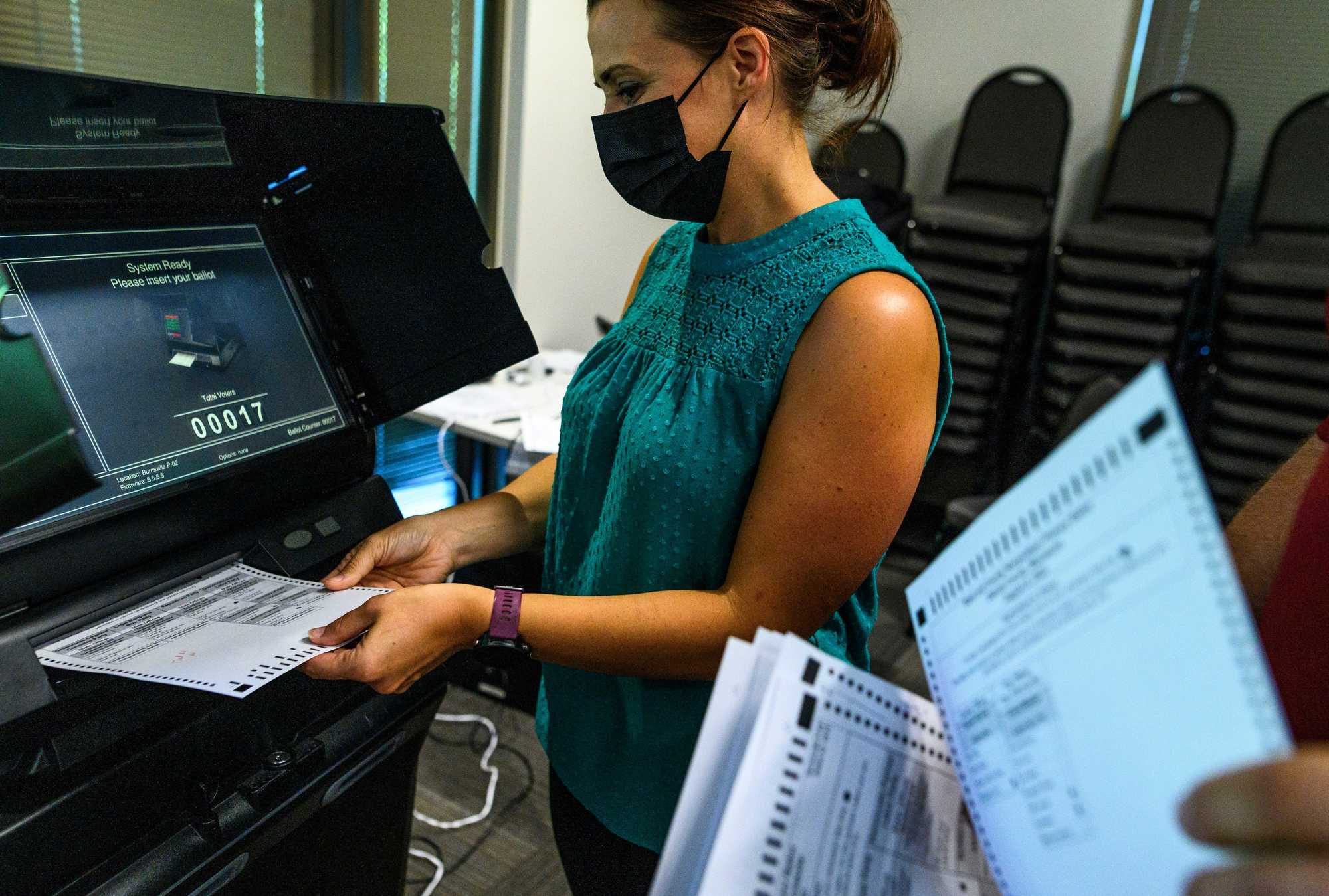

Physical equipment is another issue, technological and otherwise. The post-2000 election legislation —the Help America Vote Act — allowed states and localities to buy new machines, modernizing most of the country’s election systems. But it ended up being a one-time infusion of resources. So when the equipment reached the end of its life, there was no additional funding to replace it. That means this November, some of the machines will be almost as old as some of the voters who use them.

“It’s kind of this consistent, slight malnourishment,” said Ricky Hatch, who runs elections for Weber County, Utah, as part of his job as clerk auditor. “Election officials, we kind of roll with the punches. … You have duct tape and paper clips, and you can make it work. Now, with something this crucial, that’s not the ideal.”

On the first day of in-person early voting in the 2020 election in Spotsylvania County, Va., this struggle was on display. By midday already eight voters had come in to vote in person in the highway-side election offices despite having requested a mailed absentee ballot, which were among the 4,000 sitting in the back room stamped and ready to mail after days of stuffing and folding. Some voters had been confused or had plans change, while one man said he wanted to “test the system” if it would catch a double-vote attempt. It did.

Kellie Acors, the county’s registrar, pointed to the dollars-and-cents cost of such confusion. Creating and processing absentee ballots costs money. “It’s close to $2 a pack,” she lamented. “And that’s not even staff sitting there stuffing all of them, ordering envelopes, checking them when they come in.” That was money and staff time she was now watching literally end up in the trash.

In St. Louis County, Missouri, Director of Elections Eric Fey says his office has been able to upgrade some technology. But his peers next door in the city of St. Louis have had to obtain spare equipment from other jurisdictions across the country to keep their machines, which date to 2007, operational. St. Louis Democratic Director of Elections D. Benjamin Borgmeyer said the city has now found money to replace the machines, but between the pace of elections and limited vendor options, it’s been difficult to actually do so. In 2020, Fey said, the county received grants from the Center for Tech and Civic Life and were able to pay poll workers enough that their no-show rate went down dramatically.

It’s a perfect example, Fey said, of how a little extra resources can make a big difference. But the grants became controversial due to the center’s financial backing by tech giants including Facebook and its founder, Mark Zuckerberg. Missouri is one of 21 states that has since banned or limited the use of outside elections funding.

Fey called it “ridiculous” for elections to be held on machines so old that they almost pre-date iPhones, or to struggle to recruit poll workers on Election Day because they’re “paid a volunteer wage.”

His counterpart in Kansas City, Lauri Ealom, struggles with office space in the city’s historic Union Station building that she says regularly floods and has no security, as well as keeping and hiring staff who receive inadequate pay for a job that subjects them to unrelenting stress and derision.

“It’s just really bad,” she said. “All of my people feel like they’re doing something huge for the community in our city. But I mean, at what point — do your kids starve?”

But Missouri’s secretary of state disagreed with this assessment, downplaying concerns about funding voiced by some of his peers.

“There is not an election authority in this state that can’t run a good election because of a lack of resources from the state,” Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft said. “We have the money to run elections. But it may not just be run on 85 inch, 4K definition TVs, but we have the money to run it well.”

Fey was visibly perturbed when he heard Ashcroft’s comments relayed to him, noting that 2022 is the first time the state is picking up part of the cost of the election.

“That’s very frustrating, to me, and to most of my colleagues, for somebody to say something like that,” Fey said. “We’ll always make it work with whatever resources we have. But it can work better. And I’m not talking about having an 85 inch 4K TV. … (Right now) it’s held together by baling wire.

“It’s kind of a dirty secret in election administration, none of us can allow an election to fail, but in a sense, if an election fails somewhere and shows a weakness, then the state Legislature or Congress might actually respond to that with resources,” Fey added.

Election administrators also struggle with a shortage of another precious resource — their own time.

Aubrey Rowlatt, from Carson City, Nev., is the clerk-recorder and public administrator for her city of nearly 60,000 people. That means she’s managing the elections office as well as marriage licenses, property transactions, and public meeting records. As public administrator, she also serves as the executor of a person’s estate if he or she dies with no relatives. That means on top of everything else, roughly three to four times a week, she has to go through the affairs of city residents who pass away and figure out how to distribute what’s left.

She’s one of the election administrators who’s leaving, opting to not run for re-election this year. She’s exhausted by the demands on her time, the pressure of having to always get it right, and the fear of harassment she’s seen nationwide coming to Carson.

“I know I can administrate an election,” Rowlatt said. “But am I equipped to be also a psychologist, personal security, an understander of cybersecurity threats? … What if there’s a power outage? What if there’s a forest fire?”

Advertisement

If elections were always difficult to pull off, 2020 upped the ante.

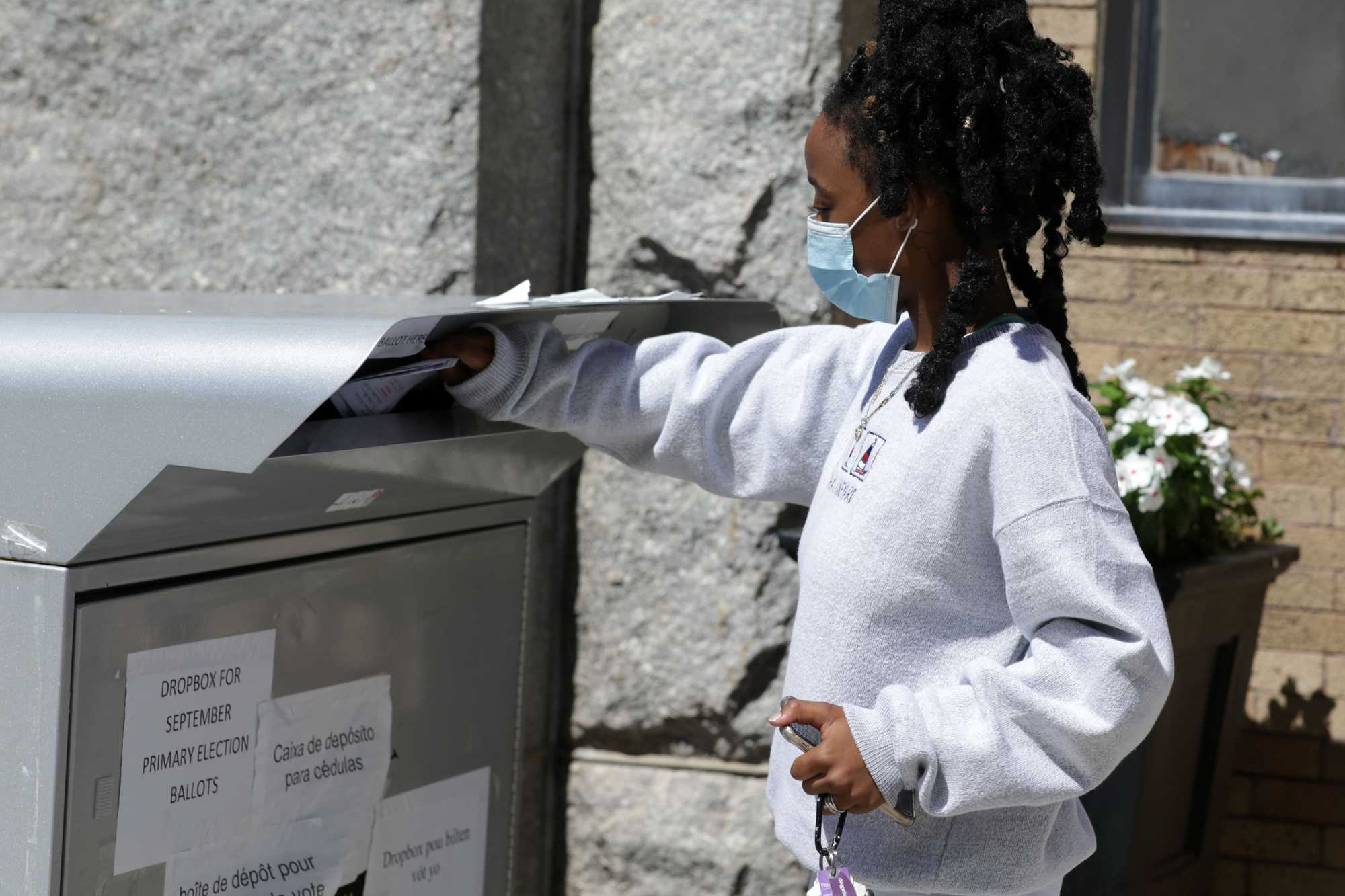

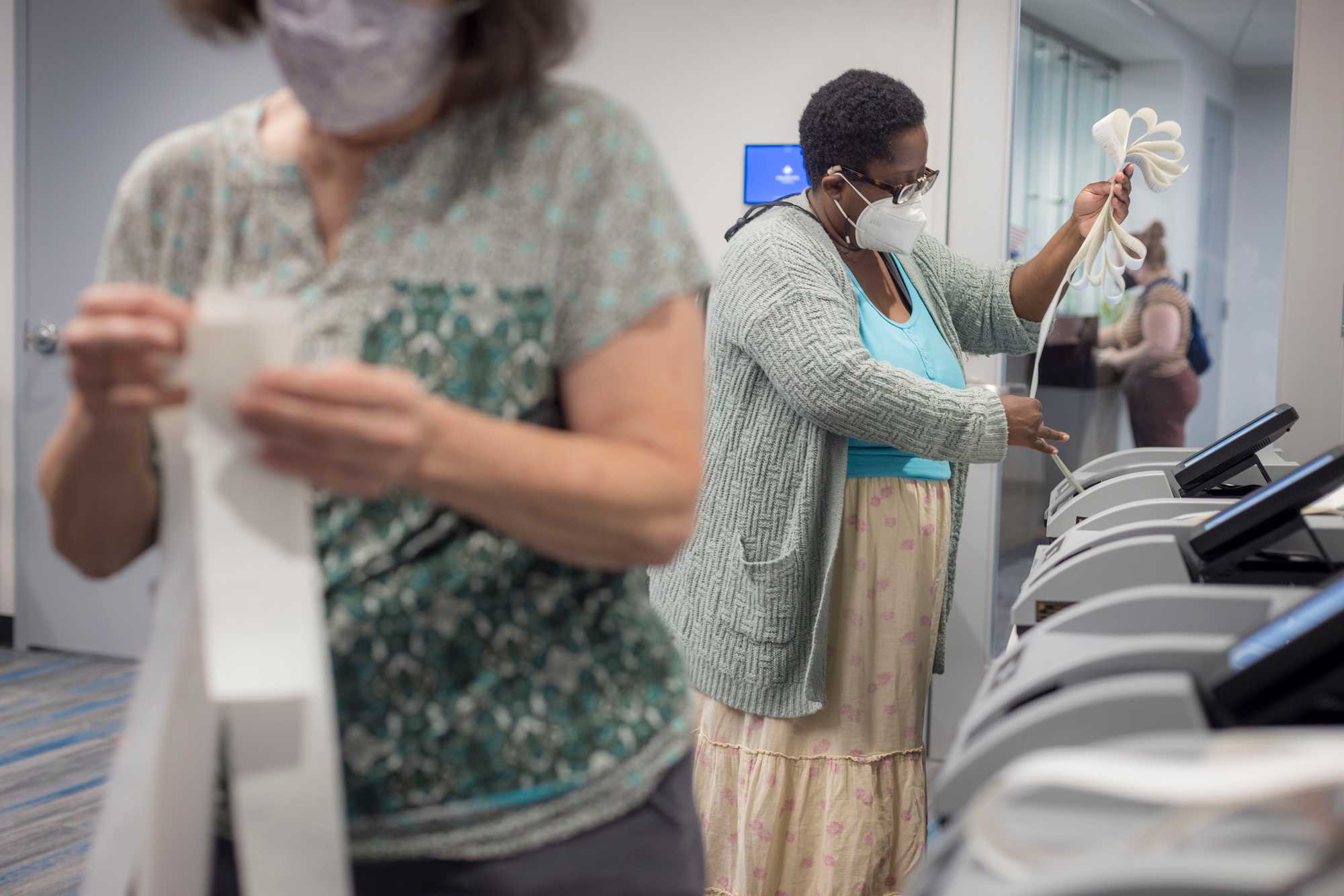

The pandemic ushered in a slew of last-minute procedural changes to keep voters safe — changes that many states stuck with this year — expanding the ability to vote by mail or vote early.

As a result, voter habits, which election officials must predict accurately to adequately conduct an election, are changing with an unprecedented level of unpredictability.

This year, election administrators are struggling to prep for an election in which voters could just as plausibly return to in-person voting as they could permanently shift to mailing their ballots, sometimes requiring them to staff up, order materials, and secure voting locations for both outcomes at once.

That’s on top of a host of new election laws written by politicians who tend to think more about the implications for their own futures and for voter access when writing laws than about implementation.

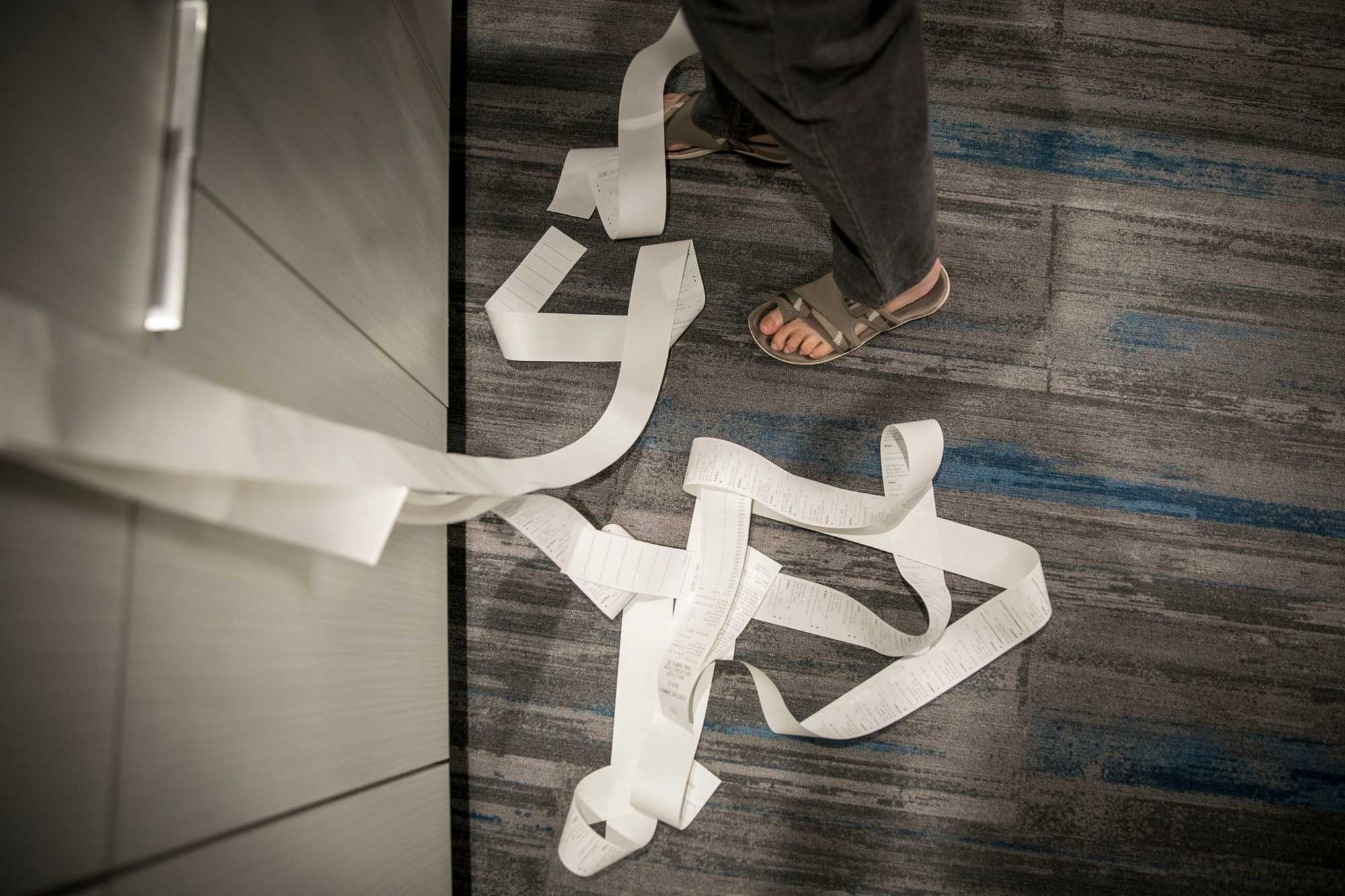

Virginia this spring passed a law requiring that results be reported by precinct, which requires precinct-specific ballots. But some counties have dozens of precincts that all use the same early voting spots, prompting many in the state this year to, for the first time, use ballot-on-demand printers rather than stocking thousands of ballots during a paper shortage and risking them getting mixed up.

Texas has a relatively new law requiring absentee voters to include driver’s license or Social Security numbers on their return ballot, which caused the number of rejected ballots to skyrocket and required a new envelope design with additional layers to preserve the personal information in transit. The new design not only increases the cost but also complicates the ballot counting process, which increases staffing requirements.

Nevada this year will mail every active voter a ballot but also allow them to vote in person, confounding election administrators like Rowlatt who are trying to predict turnout and working off unchanged budgets.

In Massachusetts, Foxborough Clerk Robert E. Cutler, Jr., who is also president of the Massachusetts Town Clerks Association, noted that a recent law making mail-in balloting permanent for presidential elections and expanding in-person early voting to two weeks before an election came with no additional funding.

“I don’t know if it’s as much an under-appreciation or a lack of understanding as to what actually goes into putting an election together,” Cutler said. “It’s not sustainable.”

Those who helped pass the Help America Vote Act in the aftermath of the 2000 election said there were key differences then that helped them get to a productive outcome. One was leadership: Gore unambiguously conceded to Bush, and leaders of Congress from both parties committed to reaching a compromise. Another difference was agreement on the problem: It was clear to anyone watching that the punch-card ballots that caused vote counting troubles in Florida (the infamous “hanging chads”) needed to be reassessed. And finally, the political environment was far less toxic.

“I remember the dismay people felt as we watched the punch-card ballots get counted and thinking that, this is the country that put a man on the moon, that created the Internet, and our election process looks like it’s a third world country,” said Neil Volz, the lead staff member on the issue for Republican Representative Bob Ney of Ohio, who sponsored the bill. “There was a united belief that we as Americans could do better than that.”

Volz recalled a moment on the afternoon of Sept. 11, 2001, when he found himself in a room with Representative Steny Hoyer, the Maryland Democrat who was the lead author of the bipartisan bill. Reeling from the terrorist attacks on the country, they talked about how to shape the legislation. Both men said it felt right to work on that issue on a day focused on patriotism.

“We discussed the larger picture, protecting democracy,” Hoyer recalled. “The ballot is how you make it work better, … giving people the opportunity, to not only vote but to feel that their vote is counted accurately.”

But 20 years later, Hoyer has a dim view of a repeat. The Help America Vote Act “could not pass today,” he said.

Veterans of elections say every presidential cycle has some productive impact on the profession. After 2000, it was massive. Other times it’s smaller, like 2012 calling attention to long lines at the polls and 2016 prompting investment in cybersecurity.

But with election denialism so extreme that it led to the violent insurrection at the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, election administrators fear only more chaos is next.

“You look at 2020, and I’m not nearly as confident that the consequences are going to be good,” said Forrest Lehman, director of elections in Lycoming County, Pa. “If the people who are showing up at meetings and posting all over Facebook are to be believed, they want to get rid of all voting systems.”

Advertisement

If there’s a single state whose election workers know what might be coming our way after the 2020 maelstrom, it’s Virginia.

The Old Dominion state is one of only two in the country that hold major off-year elections, with a highly competitive gubernatorial race in 2021. Its proximity to D.C. brings heavy national political interest and investment to the state, which made it a testing ground for right-wing election tactics. Conservative attorney Cleta Mitchell has been a major force in that effort, helping to forge coalitions of citizens into so-called election integrity groups that fan across states and question election officials. They say it’s in the name of preventing fraud, though they have no specific evidence of any significant concerns. But election administrators say, intentionally or not, the army of interrogators, observers, and antagonists spurred on by the group has taken up so much time they have little left to actually run elections.

“We got to experience the first big election in the environment that was created by 2020 and the events of early 2021,” said Brenda Cabrera, general registrar of Fairfax city and president of the Virginia registrar’s association. “Virginia found out that it was worse, really, in 2021 than in 2020.”

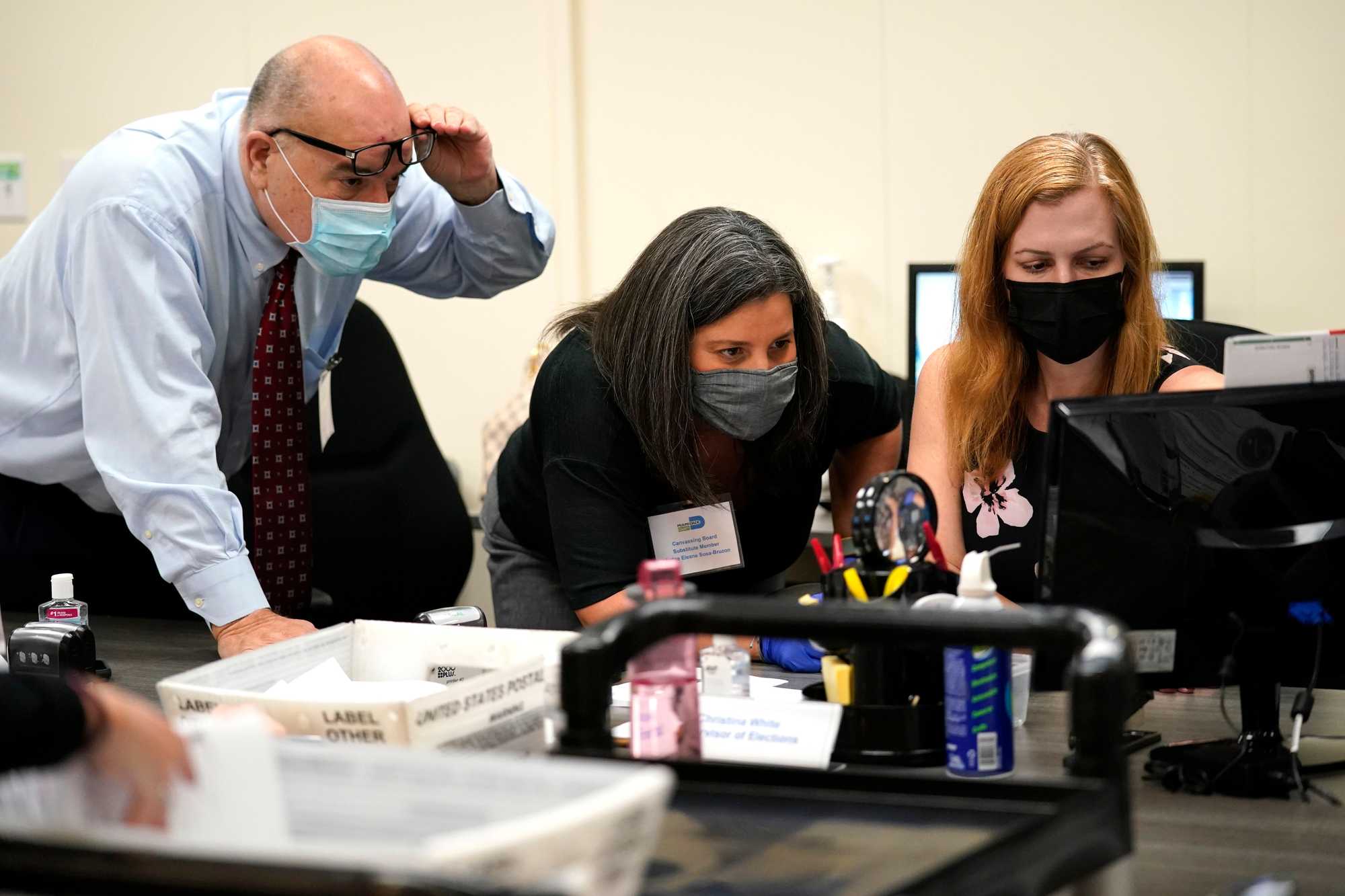

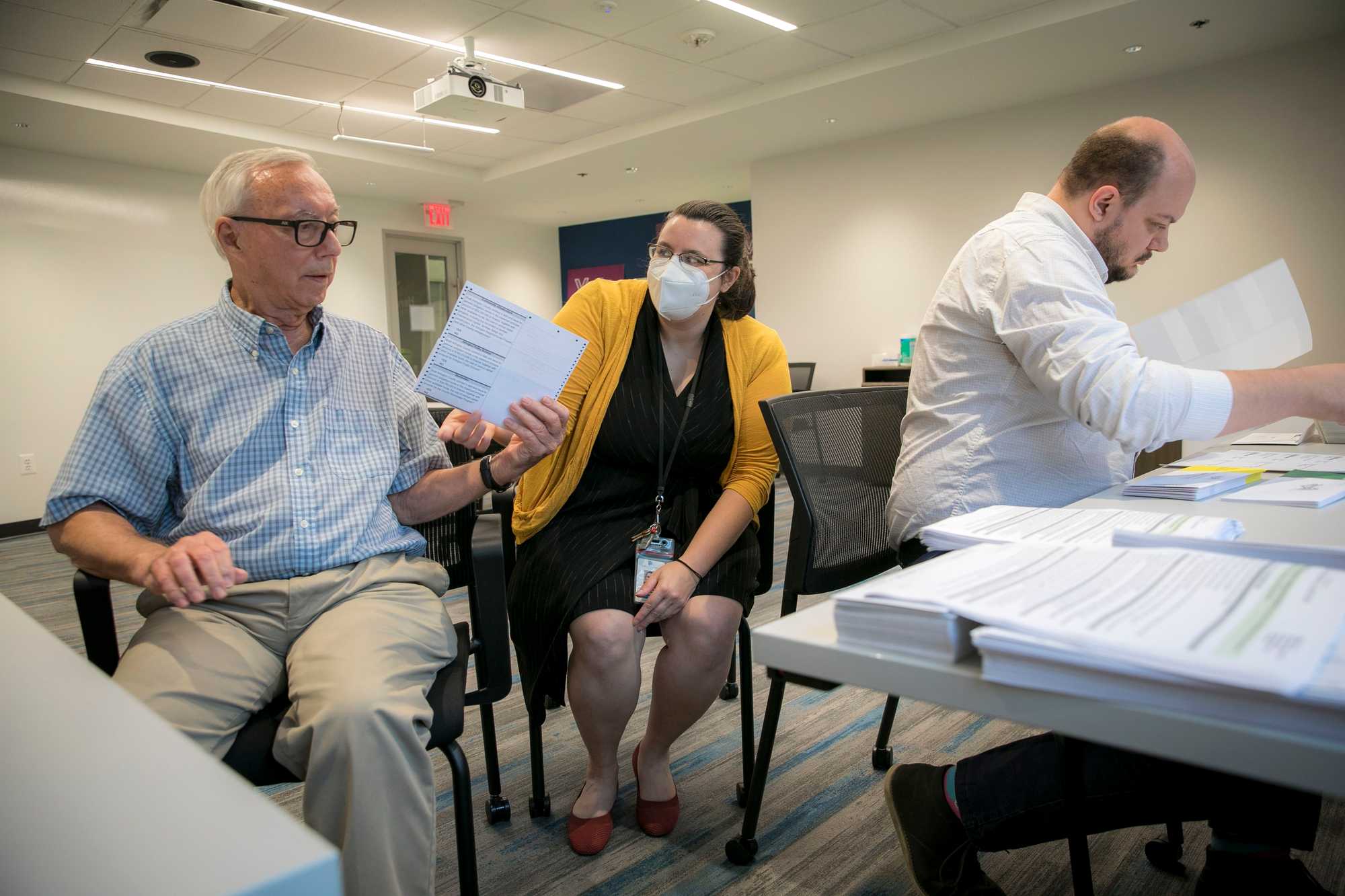

In Arlington, Va., General Registrar Gretchen Reinemeyer is on a first-name basis with her phalanx of election integrity enthusiasts. They attend and participate in meetings of her electoral board, the three-person body that oversees and appointed her. Three of them were also on hand, on behalf of the local GOP, on a Thursday in late September when Reinemeyer prepped for the imminent opening of early voting.

As she spent the morning testing the machines to be used, a standard and required step, the group posed a host of procedural questions and requests. Reading from and taking notes in a formal-looking binder, they repeatedly questioned how the machines worked, asked for a copy of the software (which Reinemeyer informed them that she neither had, nor could legally turn over), and pressed for access to employee-only secured spaces so they could stand behind poll workers checking in voters.

After the testing was complete, Reinemeyer spent nearly an additional hour speaking with the trio and answering their questions about early voting, including printing copies of the Virginia code and guidance from the state about what observers were — and weren’t — entitled to access.

In a subsequent interview, Reinemeyer said the distracting and time-draining questions have continued. While she, like most registrars, welcomes interest from citizens and relishes opportunities to educate the public about what they do, she said, the volume and apparent level of organization of the inquiries in this case are at a different level.

“We just want to run the election,” Reinemeyer said. “And so it feels like a distraction. And if we can’t focus on running the election, then inevitably, there will be mistakes, things will go wrong, and that’s the frustration. … The job is (now) less about running the election than running interference.”

Acors, Reinemeyer’s counterpart roughly an hour south in exurban Spotsylvania County, recently had to divert much of her pre-election attention to rebut a push from locals who claim to have concerns about election fraud without evidence of any. They sought to have her county — with 103,000 registered voters — hand-count the results without technological assistance. It’s a new cause célèbre among election conspiracy theorists who spread doubt about the results of the 2020 election.

A few members of the Board of Supervisors in late August allowed a presentation in favor of the plan, featuring itinerant election technology doubter Mark Cook. Acors received only a few hours warning from someone who had seen the agenda and rushed to be on scene to respond, earning herself time at a meeting a month later to give a detailed presentation explaining the misunderstandings in the original presentation. Ultimately, the county attorney made it clear that Virginia law requires the use of vote-counting technology and the board dropped the matter.

But the issue is popping up across the country. In Nevada, after a handful of counties have moved toward hand counts, the state created staffing and procedural requirements to ensure they’re done as accurately as possible. Arizona’s secretary of state is threatening to a sue a county over such a plan. Lehman faced a similar push in Pennsylvania before the elections board determined federal law wouldn’t allow it. And Hatch in Utah said he ran some numbers to put the matter to bed, calculating that hand-tabulating the results within two days of the election would take an additional 600 staff at the cost of his current total election budget of $130,000. And all the administrators agree that hand counting would introduce more error, as machines have been repeatedly shown to count faster with fewer mistakes than human beings.

Election worker turnover is increasing

The Boston Globe collected turnover data for top county election officials in five battleground states — Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin — along with four others, as well as analyzed a database maintained over time by the nonprofit US Vote Foundation. In eight of the nine states, significantly more of those workers have left their jobs since the 2020 election than departed over a similar period after the 2016 election.

Click on a state to see how the turnover rate changed from the periods between 2016 to 2018 and 2020 to 2022.

2020-2022 turnover rate

A former Virginia official who had enough of the system is Scott Konopasek. A former military intelligence officer, he has run elections all over the country since the mid-1990s, including through the tumult of 2000. He served as registrar in Fairfax County for less than a year before deciding he wanted no more of the Virginia electoral board system, nor any other election administration job.

“It’s not the profession it used to be and it’s not one that’s set up for election administrators to succeed in,” Konopasek said. “It’s tragic.”

He’s convinced after his experience in Virginia that the people organizing citizens into the so-called election integrity groups aren’t trying to improve elections but to “break” them. He said that in 2000, there were sore losers, but they presented some realistic solutions and accepted truth when it was explained to them. This time, he said, even if the individuals asking questions and making requests are genuine in their interest, the cumulative effect is overwhelming the already beleaguered system.

Those involved in making demands of election workers argue they are truly committed to the accuracy of elections, concerned about fraud or the potential for fraud in voting. They are driven, often, by a suspicion of voting technology and a vague belief that the 2020 election results can’t be right because they elected Biden by margins that were surprising to them.

Konopasek said such efforts are short-sighted, as voters who succeed in intimidating experienced administrators into quitting or slowing down the process, ultimately, are jeopardizing their own right to vote.

“It’s killing the goose that gives you the golden eggs,” Konopasek said. “Even though you haven’t taken care of the goose, even though you haven’t fed the goose very well, even though you don’t appreciate the goose … the goose is good enough to keep giving you those eggs. But if the goose is dead or gone or retired, no more eggs.”

Advertisement

The election officials who aren’t leaving have different reasons, but many say they have a sense of purpose — or a fear of who will take their place.

“I’m too mad to quit,” said Mark Earley, a more-than 30-year veteran of elections administration who runs the office in Leon County in Florida. “Elections are my thing, and it’s like a patriotic duty.”

But he said it has become ever more daunting to live up to that duty.

“It’s just a very intimidating place to work,” Earley said. “And if we leave, who’s going to replace us? … In this current environment, we’re very worried about what extremists might come in and start undermining the sanctity of our elections.”

The officials who tough it out and remain consider themselves defenders of the public faith in elections themselves — which is everything in a democracy.

“You cannot believe in the government that results from elections if you don’t first believe that the elections were fair,” said Doug Lewis, former executive director of The Election Center and an expert on elections administration. “So nothing in this society works very well if you have a distrust of the voting process. … I know this sounds overblown, but it’s not.”

Jess Bidgood, Jim Puzzanghera, Shannon Coan, Sarah Ryley, and Lissandra Villa Huerta of the Globe staff contributed to this report.

Credits

- Reporters: Jess Bidgood, Jim Puzzanghera, Tal Kopan

- Editors: Scott Allen, Mark Morrow, Jen Peter

- Multimedia editor: Christina Prignano

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development and graphics: Daigo Fujiwara

- Photo editors: William Greene and Kim Chapin

- Audio editors: Scott Helman and Jesse Remedios

- Copy editors: Mary Creane and Michael J. Bailey

- Data analysis: Shannon Coan and Sarah Ryley

- Audience engagement: Lauren Booker

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

© 2022 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC