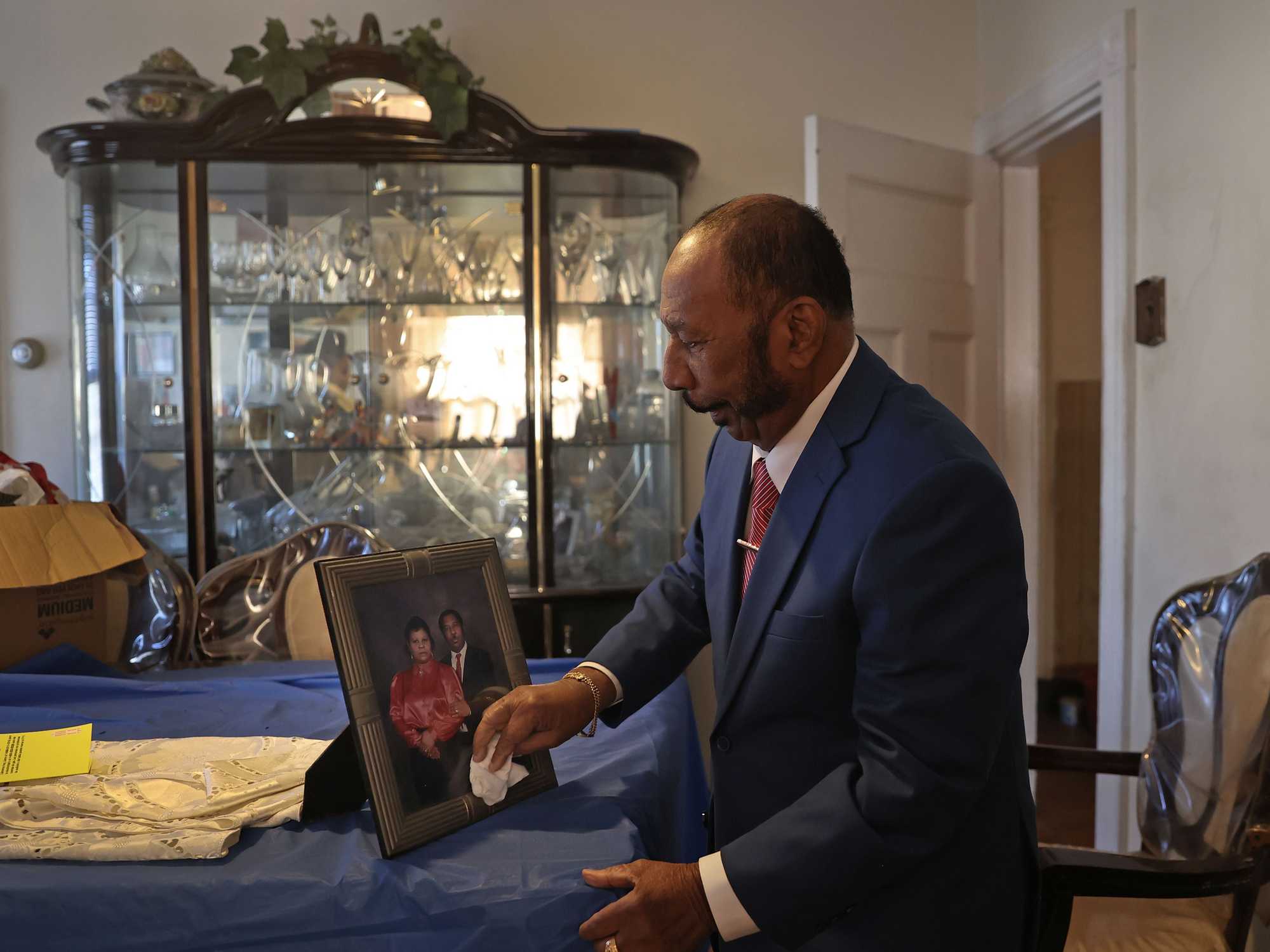

After emigrating from Haiti in the late 1970s, Thomas Duplessy set out to build a comfortable life in Boston. He soon began checking off his list of goals: He worked at a Mattapan butcher shop six days a week for just over six years until he saved enough to buy the business. Then, he and his wife, Marie Annette Duplessy, purchased a home in Dorchester, a six-bedroom where they could raise their family. And with the help of a home equity line of credit, he was able to send his nine children to college.

His children, he believed, would be set for the future. They’d go into the world with the foundation for upward mobility: a college education and an inheritance of both the home and business.

But he worries that inheritance could slip away.

Competition from a nearby grocery store forced him to close the market 20 years ago. For a time, he moved to selling cars. He’s now on a fixed income — Social Security and retirement — barely enough to afford his utility bills, make repairs on the house, and finish paying off the second mortgage.

Mobility issues have put Marie Annette in a nursing facility as her husband races to make modifications to their home so that she can return by the end of December, in time to celebrate his 80th birthday with their family.

There have been offers on the house from developers — even cash offers — that could make life easier. But he has refused them. The home is modest by Boston’s standards, but it’s something. And it’s his. Cashing out now might mean an infusion of cash in the short term, but would it be enough to buy another property in the city? Would there be anything left to leave his children? A developer could turn his family home into new condos, like the ones now across the street: eight three-bedroom units that sold for nearly $4 million combined between 2018 and 2020.

Duplessy could never hope to reap that kind of profit from the property on which he staked his American dream.

For generations, home ownership has been like holding a golden ticket, a type of fortune that Americans have used as a way to build generational wealth.

It’s why Duplessy has refused to sell. “That’s my kids’ house,” he said.

But for a web of complex historical reasons, Black families like his rarely have it so simple. Black people for decades have faced an array of racist and exclusionary obstacles that have prevented them from buying homes. And when they do buy homes, systemic disparities can make it tougher for them to hold onto them — or make basic repairs. Even now, for those who do manage to buy in, biased real estate practices and de facto segregation determine how much a home is worth, and, in essence, how much wealth families will eventually transfer.

The result is a yawning racial wealth gap, exacerbated by disparities between those who can afford to purchase a home, keep it, and pass it on to future generations, and those who cannot. According to 2022 estimates, white Bostonians have a net worth 19 times higher than Black residents and more than 37 times higher than Latinos.

As city and state leaders explore ways to narrow the gap, what is clear is that homeownership can’t be the cure-all to solve generations of inequality — at least not on its own. And not unless policymakers are deliberate in confronting the racial imbalances that have allowed the gap to widen.

“We shouldn’t hold homeownership up as the way [to close the wealth gap] if we’re not also equally committed to fixing the system,” said Shanti Abedin, vice president of housing and community development at the National Fair Housing Alliance.

“It would take us centuries to close the racial wealth gap if we continue on the path that we’re on without intervention,” she added.

That means addressing current segregation and housing discrimination by eliminating exclusionary zoning codes, Abedin and other housing experts say, that have stymied the construction of new homes, created a housing shortage, and prevented neighborhood growth. Doing so, they say, would help Black and Latino families live where they want and see their home values (and, more importantly, wealth) rise at the same rates as white households.

It means providing equal access to better loans, and supporting low-income families with down-payment assistance. And, because Black and Latino households tend to have far less income than white households, and more debt, it means providing support when a head of household faces an unexpected hardship, such as the loss of a job or the accrual of medical bills.

In recent years, advocates have called for even bolder action, such as reforming the ways that banks use credit scores in considering whether to grant a loan. They have also pushed for more special-purpose credit programs that, by their nature, specifically target Black and Latino households.

More plainly, to bridge the gap, housing and civil rights advocates say, lawmakers must act with the same level of purpose that the government had when it first created the racist systems that prevented people of color from attaining wealth.

“Of course we have a wealth gap, of course we have a homeownership gap. It is intentional,” said Chrystal Kornegay, CEO of MassHousing, which supports first-time homebuyers and developers that build affordable housing.

“And that’s why we can fix it,” she said, “because intention is what is needed to do that.”

While homeownership is a path to building wealth, the amount of wealth a home provides often depends on its location. Median home values vary across Boston, with dwellings downtown and in neighborhoods on the city’s edges being the most valuable. But residential segregation and income inequality shape who has access to the most valuable houses.

Due to decades of de facto segregation and structural racism, homes in neighborhoods with majority Black or Latino residents (highlighted in red) generally have lower home values compared to houses in other parts of the city.

Majority white neighborhoods (highlighted in red), on the other hand, are more likely to have some of the most valuable properties in the city. The average median home value in white areas is $735,000 compared to $473,000 and $461,000 in predominantly Black and Latino areas, respectively. So while housing real estate may increase wealth for Black and Latino families, simply helping them buy homes will not be enough to close the racial wealth gap unless there’s also an increase in Black and Latino home values.

Wealth, by where you live

Boston’s housing market is booming. In July, the median sales price for single-family homes in the city hit an eye-popping $910,000, according to a Greater Boston Association of Realtors report. Even condos are selling at record prices.

But how much money a person’s home is worth often depends on two things: their skin color and where they live, factors that are inextricably linked.

A Globe analysis of 2021 US Census data shows the average median home value in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods was $473,000 and $461,000, respectively, compared with $735,000 for homes in mostly white neighborhoods. The numbers are a stark representation of how decades of de facto segregation and structural racism have helped widen the racial wealth gap, even when Black and Latino people do everything right to narrow it.

Take, for example, the Duplessys, who bought their home in 1986 for roughly $200,000, settling in Codman Square, a mostly Black and Latino community that fell victim to redlining and disinvestment in the 1960s and 1970s. They saw the neighborhood as welcoming and up-and-coming, with nearby parks for their children.

“Together, we could do anything we want,” Duplessy recalls himself and his wife saying.

An estimate by the home-buying website Redfin — which has a 6.42 percent median error rate for off-market homes in Massachusetts — shows the Duplessys’ two-family home could sell for roughly $787,000. The value is far below the September median sales price for two-family homes of $920,000, according to the realtor group’s report.

One major factor: The Duplessys’ home is in a neighborhood that is still largely Black and Latino, and because of that, its value is lower.

Additionally, homes in predominantly white neighborhoods appreciate at a faster rate compared to homes in Black and Latino communities. Between 2011 and 2021, the average median value of homes in predominantly white areas grew roughly 66 percent. Meanwhile, homes in Black communities increased 40 percent and in Latino communities jumped 50 percent.

So while housing real estate may increase wealth for Black and Latino families, simply helping them buy homes will not be enough to close the racial wealth gap unless there’s also an increase in their home values.

“People need the ability to grow their assets,” said Rachel Heller, of Citizens Housing and Planning Association, who pinned segregation and disinvestment in Black and Latino communities as the driving factor in widening the wealth gap.

“That’s a whole conversation, of why do we have a racial wealth gap and how much does housing play into that,” she said. “All of this lasts for generations.”

Areas with homeowners who are predominantly Black or Latino (highlighted) are often locations with some of the lowest median home values in Suffolk County, further pointing to the impact of structural segregation on wealth.

Areas with the most Black homeowners also have some of the lowest income levels in the city, highlighting how race, income, and the neighborhoods in which people live are linked.

Latino communities have the lowest median incomes in Suffolk County, census data show. As a result, areas with the most Latino homeowners (highlighted) tend to also have the lowest income levels. Homes in Latino neighborhoods are also the least valuable in the city, with an average median value that is $275,000 lower than houses in white areas.

For white homeowners, the majority (highlighted) live in areas with higher median income levels. The average median income in areas with the most white homeowners is $111,000, compared to $80,000 for Black homeowners and $70,000 for Latino homeowners.

And still today, potential home buyers and realtors say, discrimination in the real estate market and in lending practices persists, often in the form of appraisal bias, in which a housing appraiser’s unconscious bias seeps into their estimate of a home’s value.

In 2021, for instance, a study by the federal home mortgage corporation Freddie Mac of more than 12 million appraisals found homes in Black and Latino communities were undervalued far more often (12 and 15 percent of the time, respectively) than they were in white neighborhoods (7 percent of the time).

A low appraisal can affect how much a home can sell for. It can also determine how much equity a homeowner can claim when applying for a line of credit or taking out a second mortgage.

Hakim Cunningham, a lifelong Dorchester resident, suspected appraisal bias was at play after he and his sister acquired their mother’s triple-decker in 2020, after her death.

The home needed repairs, he knew that. Through his studies in college, he also knew how to navigate the mortgage process and appreciate a home’s potential value, especially in an up-and-coming neighborhood that developers now call East Codman Hill.

What baffled Cunningham was how quickly the appraisal of the home changed — after a few renovations, and after a new, nonwhite appraiser viewed the property.

His triple-decker that was assessed at $750,000 in 2020 jumped in value in only a couple of years, to $1.1 million.

While the bump is partly due to the market’s explosion, it is also because the nonwhite appraiser saw the home’s true worth: It should be valued for what it was, three separate condos, rather than a single building that could be flipped by a developer.

The change finally gave him more equity to pay for repairs and restorations.

Now, Cunningham and his sister are stewards of their mother’s dream home, but they wouldn’t call themselves rich, either. They live on the first floor and rent out the other units, and make ends meet while they hold daytime jobs.

“There’s no super wealth being made from getting a few rents a month,” he said.

Regardless, he and his sister had told themselves, “We’re not selling this. This should stay in the family, if we look at long-term ownership and long-term value.”

‘I just wanted to stay in Boston’

Even the most righteous efforts to boost homeownership for low- and moderate-income families can have their limits when it comes to closing the racial wealth gap.

Take, for example, the Saige on Fountain development in Roxbury: With all of its 40 units designated as affordable (buyers must make below 100 percent of the area’s median income, or no more than $108,750 for a two-bedroom unit, and in some cases even less), it is the largest such development in Boston.

Unveiled in October, the $21.9 million project was heralded as a model for public and private partnerships to build more affordable housing; it includes funding from city programs as well as $5 million from MassHousing’s CommonWealth Builder program, which specifically supports affordable homeownership projects. The development also taps into city and state programs that offer down-payment assistance and better interest rates, helping buyers who make far less than the restriction caps afford some of the units.

But owning one of the condos — some of which have views of the Boston skyline — has its limitations. They don’t cost much: as much as $356,000 for a three-bedroom and as little as $165,000 for a studio. But they come with deed restrictions, which limit any sale of the property within the next 30 years to someone who meets income caps. Put more simply, owners of the condos can’t sell them later for market value, limiting the amount of wealth they can accumulate as the housing market continues to boom, and the amount of wealth they can pass on to the next generation.

There is a tradeoff, though: housing stability. In Boston, where the median rent for a two-bedroom is $3,390, owning such a home means paying less on a mortgage without the burden of housing insecurity. And a homeowner can transfer the property to a beneficiary, such as a relative, who does not meet the income limits — so not transferring wealth, necessarily, but keeping a stable place to live within the family.

And that’s the intent: to keep the units affordable and in a family for generations. Dariela Villón-Maga of DVH Housing Partners, one of the co-developers, said she tells potential home buyers, “This is your starter home, and this is going to be a starter home for generations to come.”

You’d be hard pressed to find a new resident at Saige on Fountain — chosen out of a lottery of 882 applicants — who isn’t ecstatic to own a piece of Boston real estate, especially amid the worsening housing crisis.

Aisha Virgo, 31, grew up in Dorchester seeing other family members pushed out to communities south of Boston. The daughter of Jamaican immigrants who taught her the value of owning a home, Virgo said the income-level restrictions at Saige on Fountain were the only reason she could afford the unit and remain near her parents.

Now, she can see the cityscape from her one-bedroom.

“I just wanted to stay in Boston,” said Virgo, a university relations officer at State Street, the Boston-based financial services company.

Murad Wornum, who grew up in Roxbury near the development, almost gave up on buying in Boston five years ago, after he was priced out whenever he tried.

Aisha Virgo stood in her new home at the Saige on Fountain development in Roxbury. (David L. Ryan/Globe Staff)

Wornum, 46, a grants manager at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, had taken part in support programs for first-time home buyers, from attending home buyer education classes to applying for public grants.

He eventually secured down-payment assistance, and had his interest rate reduced. But it took winning one of the coveted Saige on Fountain lottery slots to purchase his first home.

“I had resigned myself to the fact that I was not going to be able to live in Massachusetts anymore,” he said. “But everybody was intent on having people in this community stay in this community.”

He now has a sense of stability, he said. Something he can pass on to his two children. It may not amount to wealth now, but it’s a start.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/bostonglobe/6DNQFOWNBBDUHE74PST34FRI6I.jpg)