A rogue cop, a mystery snitch, and a ‘drug rip.’ How ‘Officer Pills’ exploited policing’s informant system.

NEW BEDFORD — During daylight hours, the docks of this city’s historic port are a hive of activity — dive-bombing gulls, rumbling diesel trucks, and the playful banter of fishermen.

When night falls, the fishermen retreat to crowded triple-deckers or waterfront hotels and silence takes over, the only sounds coming from hulking boats that sway gently in Buzzards Bay.

Among them, on an early summer night in 2018, was the Little Tootie, a rust-scabbed scalloper based out of Newport News, Va., set to depart the next morning on a 10-day fishing trip down the Atlantic Coast.

Below deck, a handful of fishermen prepared for their journey. Some lay down to sleep.

Shortly before 9:30, they heard pounding on the wheelhouse door.

The stranger was dressed in black. His eyes were bloodshot. He had a pistol on his hip.

The Globe commissioned illustrations of key events for this series. In order to avoid identifying certain sources, we chose not to depict specific individuals. Illustrations are instead an artist’s rendering of events, people, and concepts.

He pushed his way into the cabin, barged into the bunk of a sleeping fisherman, and dug furiously through the man’s pockets.

Where are the drugs?

Jolted from sleep, the fisherman pushed and struggled to fight the intruder off.

An informant told me you’re bringing drugs on the boat! the intruder shouted.

Amid the melee, a crew member dialed 911.

The call that came in to the New Bedford Police Department’s dispatch center, a mile or two away, was short on details. A man had forced his way aboard. He was claiming to be a cop.

Even with this scant description, one name crept into the minds of the dispatchers.

Jorge.

Fishing boats were tied up in New Bedford, near where the Acushnet River empties into Buzzards Bay. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

Within the department, Jorge Santos was a rising star. Barely 30, he was part of a specialized squad — the marine unit — tasked with overseeing a stretch of the city’s busy waterfront. Brash and aggressive, he won raves for his work ethic from supervisors, his impressive arrest totals recounted in the local media. In policing’s vernacular, he was a worker, the kind of hard-charging officer who delivered the stats that made bosses look good.

Among many in the department’s rank-and-file, however, Santos had a far different reputation. He’d long been known as a loose cannon, a reckless officer who cut corners and maybe more.

A colleague in the marine unit had warned police higher-ups that Santos was a liability. Officer Mark Raposo told supervisors he would no longer back up Santos on calls because he didn’t want to put himself in legal jeopardy.

Now, Raposo was getting radioed by dispatch and ordered to sort out what exactly was happening aboard the Little Tootie.

A veteran New Bedford cop with a wrestler’s build, he parked his cruiser on the dock, clambered aboard the Little Tootie, and stumbled into a scene that defied explanation.

When Officer Mark Raposo arrived on June 21, 2018, the scene aboard the Little Tootie in New Bedford defied explanation. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

Advertisement

Screaming. Fighting. Shouts about pills and money.

And in the middle of the scrum stood his colleague, Santos, mumbling about a “confidential informant.”

It was a term Santos had used time and again. Having a confidential informant — a CI — meant Santos had information that no one else did. That gave him a hall pass of sorts, a shield against the kind of questions that might otherwise be asked of him. Like: Who is this secret source of yours?

Raposo stood there, befuddled. What was his colleague — off-duty, armed, alone, and without a warrant or any paperwork — doing here in the middle of the night, tussling with some out-of-town fishermen?

This wasn’t some clandestine police operation, Raposo thought. It was a robbery, a “drug rip,” in Raposo’s words. The perpetrator was a fellow cop.

And the supposed confidential informant behind it?

Probably a fabrication, Raposo figured.

Listen to the podcast

Informant, CI, snitch. Officer Jorge Santos knew well the weight of the word and the power it conferred — whether or not the CI was real.

With Santos, it was often a question. But given his track record of uncommon results — in arrests, drug seizures, and the like — it was not a question his superiors were much inclined to ask.

His behavior and their acquiescence epitomize the dark, unexamined underside of the world of police and informants.

In the decades since America declared war on drugs, law enforcement’s reliance upon informants has become nearly absolute. Today, in cities across the country, almost every drug investigation of any significance can be traced back to the word of a confidential informant.

It is impossible to overstate their importance. Their tips can launch investigations, sway judges, and upend lives. Yet, police direct and oversee this vast, anonymous army with virtually no oversight, no regulation, and no transparency.

In this vacuum of scrutiny, police misconduct and corruption have been allowed to fester across Massachusetts, the Globe Spotlight Team has found. A yearlong investigation has uncovered instances in which officers have invented CIs, had sex with informants under their purview, and used informants to settle scores, protect drug dealers, or break the law.

(J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

Among the Spotlight Team’s findings:

- Dozens of Massachusetts agencies — including one of the state’s 10 largest police departments, Brockton — have no policy governing the use of informants, a fact that one criminal justice expert calls “insane.” More than three dozen departments in the state allow the use of unregistered informants, who are unvetted and go untracked.

- Nearly nine in 10 drug raids hinge on the word of a confidential informant, according to a Spotlight Team analysis of more than 2,000 search warrants from courts covering 16 Massachusetts municipalities, including Boston, Worcester, and Springfield. In New Bedford the rate was even higher: 99 percent. The overwhelming majority of drug warrants are based on the word of just a single informant whose veracity is almost never questioned.

- Eight of the 10 police departments from the state’s largest cities refused to provide the Spotlight Team with even basic, anonymized data about their informants — including how many are currently in use, how much informants have been paid with taxpayer dollars, and more.

These local lapses mirror a pattern of informant abuse across the country, Spotlight found, where nearly every aspect of the CI system is shielded from the public.

“The culture of secrecy surrounding informants is an enormous problem not only for our criminal justice system, but also our democracy,” said Alexandra Natapoff, a law professor at Harvard University and a top expert on confidential informants. “It prevents the American public from knowing how law enforcement actually behaves.”

In practice, police can attribute information to a CI with near-certainty that they will never be compelled to produce their source — or even describe them — in court. This creates a system that rests on blind faith in police.

“These officers and detectives are given a virtual blank check by the courts, and they know it,” said Mark Booker, a Fall River defense attorney.

The system ignores the reality that cops sometimes lie.

They lied in cases brought in Oakland and Baltimore, in New York and Los Angeles. They lied in San Francisco, where a drug cop’s illicit relationship with an informant has led to the dismissal of at least 82 drug cases. And in Houston, where in 2019, a middle-aged couple were shot to death by police as they executed a search warrant based on false information attributed to an informant.

So it is no surprise that some have lied in Massachusetts, home to some of the nation’s most notorious informant scandals. Think: Whitey Bulger, the violent Boston gangster who moonlit as an FBI informant.

To peel back the curtain guarding this shadowy world, the Spotlight Team spent the past year investigating Massachusetts law enforcement’s use of informants. Reporters conducted more than 100 interviews with people from all corners of the criminal justice system, including informants themselves. The Spotlight Team requested data from each of the state’s 400-plus law enforcement agencies and examined 2,000 search warrants from courts covering 16 municipalities, including the state’s three largest cities.

What has emerged is a troubling portrait of the criminal justice system’s clandestine corner.

The New Bedford police station at 781 Ashley Blvd. The New Bedford Police Department has had a troubling history when it comes to its use of confidential informants. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

Nowhere have things veered further off the rails than in the city of New Bedford. There, some officers have exploited the secrecy of the informant system in almost every way imaginable: to enrich themselves, protect drug dealers, and attack perceived enemies — all with impunity.

In just the last few years, the Spotlight Team has found, officers in New Bedford have invented informants or urged them to lie in court. They’ve slept with informants. And they’ve been accused of directing informants to plant drugs on police targets, of providing informants with sensitive police information, and of failing to protect informants’ identities.

In this city as in many others, informant-related abuses not only go unpunished, they can serve as a precursor to promotion.

Two decades ago, a federal Drug Enforcement Administration whistle-blower warned that informant misconduct in New Bedford had grown so rampant — and veered so far from the norm — that the city was on the verge of another “Whitey Bulger incident.”

It may only have gotten worse.

The story of Jorge Santos exemplifies the risks — and the potential for corruption — in the system.

For years, people whispered about him along the waterfront, from atop barstools and aboard fishing boats with such names as Predator and Injustice.

They spoke of him like a bogeyman — the officer who made his own rules, who allegedly took what he wanted, who answered to no one, who supposedly had sources like nobody else.

Officer Pastillas, they called him.

Officer Pills.

Get Snitch City in your inbox

Sign up to receive Spotlight reports and special projects, like Snitch City

Santos was a product of New Bedford, a graduate of the city’s vocational school. At 5-foot-9, with pudgy cheeks and a pleasant smile, he wasn’t especially imposing. As a police recruit, he was considered earnest but raw — supervisors had to remind him of the dress code. But he was eager to work.

“He was a little on the uneducated side, rough around the edges, would go to fists over disrespect,” said a current New Bedford officer, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “But he was trying to do a lot of work and asking questions of older guys: ‘How do you do this? How do you do that?’”

From the outset, Santos grasped a key insight: The surest path to a coveted assignment was to deliver the stats — stops, citations, arrests — that serve as the department’s lifeblood.

His 2011 hiring coincided with the election of Mayor Jon Mitchell, a former federal prosecutor who’d campaigned, in part, on a promise to clean up the city’s crime problem (“I am the last person criminals want to see in the mayor’s office,” he declared during his campaign).

Early in his career, Santos stood out. Some patrolmen went weeks without making an arrest, but Santos would sometimes make a half-dozen in a single night.

Over a five-year period, department records show, Santos ranked sixth among 185 New Bedford officers for his street interactions — a metric that documents an officer’s production — despite being on duty for about half that period.

He was seen as both a standout and a caution. At least eight colleagues described Santos as a walking internal affairs case.

There was the time he was kicked out of a training event on Martha’s Vineyard after drunkenly trying to fight an instructor, a colleague said. Another time, he was inadvertently left behind on a fishing boat after carrying out an unauthorized search.

Advertisement

As one former New Bedford detective put it, echoing what several others told the Globe: “Whenever you’d back Jorge up, it would be, ‘Am I going to end up in Professional Standards over this? Is this going to be a career-killer for me?’”

Co-workers say Santos’ productivity afforded him an extra-long leash.

While a colleague once received a five-day suspension for supposedly joking about the number of officers present at an arrest scene, Santos wasn’t disciplined after he engaged in a high-speed chase without calling it out over the radio — it came to light only after frightened witnesses began dialing 911.

In 2017, Santos got his first big break. A new sergeant wanted him for the waterfront marine unit.

To some, it seemed an odd choice. Santos seemed unqualified — for example, he’d never served on the department’s dive team, a typical prerequisite.

Formed a decade earlier in large part to help discourage and investigate boat break-ins, the marine unit assisted the Coast Guard and the Massachusetts Environmental Police with occasional vessel searches, carried out recovery missions, and maintained relationships with the boats, businesses, and people on the waterfront.

Almost overnight, former colleagues and fishermen said, Santos made it his playground, his cruiser cutting an endless loop, back and forth, along the piers. He used low-rent tactics that left those on the docks rolling their eyes.

New Bedford marine unit Officer Jorge Santos became a fixture along the city's waterfront, often conducting questionable stops of fishermen and asking them if they were carrying pills. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

One fisherman recalled the officer wandering the waterfront in dark sunglasses and a low-brimmed cap, seeking an undercover job on a boat. Another told the Globe he’d once observed a man he believed to be Santos dressed in a suit and tie, attempting to buy drugs while speaking in a fake Italian accent.

But it was his traffic stops that set him apart.

Even for a population well-versed in racial profiling — a 2021 study by Citizens for Juvenile Justice found that New Bedford police stopped Black and brown people at significantly disproportionate rates during the late 2010s — Santos’ stops were different.

He rarely asked for a driver’s license or registration. He rarely radioed for backup.

He typically asked just one question of motorists, as his shadow darkened the driver’s side window.

Where are the pills?

New Bedford has always been a city of opportunity.

It can be difficult to imagine now, but this city was once America’s wealthiest. Its cobblestone streets were immortalized in the pages of Melville’s “Moby-Dick.” At its apex, in the mid-1800s, it was home to more than 300 whaling ships. It harvested so much whale oil that New Bedford became known as “The City That Lit the World.”

The decline came quickly.

By the early 1900s, petroleum and Edison’s lightbulb had rendered whaling obsolete. For a time, the city successfully pivoted to textiles. That, too, faded as the industry moved south or overseas, and the city entered a decades-long slide.

The drug trade was a natural to enter that void. Home to a sizable port, as well as a small airport, New Bedford was well-positioned along the corridor between Boston and Providence.

Crime and poverty spiked. Heroin and cocaine poured into the city, followed by pills and fentanyl. Drug operations became family affairs, passed, like heirlooms, from one generation to the next.

Fishing boats docked along State Pier in New Bedford. The city's port has a storied history, helping the city become America's wealthiest in the days of whaling. In "Moby-Dick," Herman Melville wrote: “Nowhere in all America will you find more patrician-like houses; parks and gardens more opulent, than in New Bedford.” (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

And though the city’s bustling harbor continued to anchor New Bedford’s economy — it still routinely ranks as the most lucrative commercial fishing port in the nation — it also grew into a haven for lawlessness. Organized crime and drug and human smuggling have all found a home here.

By the early 2000s, a new wave of immigrant laborers arrived.

Where Portuguese and Cape Verdeans once toiled, now it was Central Americans — men and women from Guatemala and Honduras and El Salvador.

The fortunate ones landed jobs aboard fishing boats; others made do in the stink of the processing plants, where the work could be back-breaking but the bosses didn’t look too closely at working papers.

Soon, the new arrivals were a constant and conspicuous presence along the waterfront. They typically spoke little English, carried their earnings in cash, and harbored a distrust for law enforcement — fueled by their immigration status — that made them reluctant to go to police.

To someone looking to take advantage, in other words, it was hard to imagine a more perfect target.

A reporter need only to utter the word “Pastillas” to get a reaction from folks along the harbor. Nearly every Spanish-speaking worker has a story. Even some Massachusetts natives had run-ins.

Kyle Curran, a second-generation New Bedford fisherman, told the Globe he’d been carrying 10 illegal suboxone strips when he was arrested by Santos for drug possession in August 2017, yet only three strips got documented in his arrest report.

A Spanish-speaking fisherman, arrested by Santos for possession of 15 pain pills, later told authorities he was positive he’d had 20. (Prosecutors later dropped the charges against both men.)

Nearly every Santos stop — according to police records, court files, and interviews with current and former members of the Police Department — started like this:

Where are the pills?

(J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

Next, Santos would squeeze his target, offering leniency if they would be his informant. He was obsessed with developing informants, colleagues said.

One fisherman arrested by Santos said the officer drove him around for 45 minutes, demanding to know where he could find pills. Another time, a fellow officer arrived at the unit’s small waterfront office to find a ragged man, just sprung from jail and clearly impaired. The colleague thought the man needed an ambulance. Santos was attempting to enlist him as an informant, the colleague said.

It was an obsession that made little sense. In policing, informants are used almost exclusively to develop the probable cause necessary to obtain a search warrant for a home or vehicle. But in his entire career with New Bedford police, records show, Santos would obtain only a single search warrant – and that was around the time he joined the marine unit, in 2017.

Once, Curran said, Santos questioned him while driving Curran to be booked on an outstanding warrant. When the officer asked whether he was aware of drug use on the waterfront, Curran scoffed.

It’s the docks, he replied. Everyone has drugs.

Instantly, Curran said, Santos turned the cruiser around and returned to the waterfront, where — armed with nothing more than Curran’s throwaway remark — he conducted a lengthy, off-the-books search of a boat while Curran remained handcuffed in the car.

Alfredo “Freddy” Loya remembers standing on the shoulder of MacArthur Drive, along the city’s waterfront, and watching Santos dig through the cab of his pickup.

Pastillas? Again?

Though based in Virginia, Loya’s work brought him regularly to New Bedford. He first encountered Jorge Santos in 2017.

The New Bedford-Fairhaven Bridge cast a shadow over MacArthur Drive. Fisherman Alfredo "Freddy" Loya once confronted Officer Jorge Santos here after Santos allegedly stole pills from him. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

Their initial introduction had been cordial. After pulling Loya over, Santos had asked to search Loya’s truck, explaining that he was part of a task force targeting drugs on the waterfront. To Loya, who’d seen how opiates had eviscerated the fishing community, it seemed a worthy endeavor.

But by the third or fourth time Santos pulled him over — each time carrying out a lengthy search — any goodwill had vanished.

Now, as he stood watching the officer conduct yet another dubious search, Loya fumed.

He was still angry a couple hours later when, back in his truck and a few miles into the long drive home to Virginia, his son-in-law motioned to the center console.

Did you see what he took? the son-in-law asked.

“Former New Bedford detective“Whenever you’d back Jorge up, it would be, ‘Am I going to end up in Professional Standards over this? Is this going to be a career-killer for me?’”

A prescription bottle of Adderall belonging to Loya’s wife was missing.

Furious, Loya turned the truck around, returned to New Bedford and scoured the waterfront until he found Santos, parked under a bridge and sitting in his cruiser. After a tense exchange, Loya said, Santos returned the prescription bottle of 100 or so pills – but only after attempting to recruit Loya as an informant.

As Santos’ behavior escalated, some dock workers began avoiding the waterfront when not working.

Others, emboldened by a few drinks, spoke of taking matters into their own hands.

One night, Loya recalled, he listened as a few fishermen talked of violence. They wanted the officer dead.

It was just talk, Loya says now, a little alcohol-fueled bravado.

But early one morning in September 2017, firefighters were summoned to the officer’s home. They found Santos’ take-home cruiser in flames.

In September 2017, Officer Jorge Santos' take-home cruiser suddenly burst into flames in front of his home. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

A New Bedford Fire Department report noted the early-morning blaze was likely the result of an electrical issue or equipment failure, an explanation that elicited chuckles from officers.

Said one former New Bedford officer: “I’ve never heard of a car suddenly bursting into flames for no reason.”

Among beat cops in New Bedford, Jorge Santos’ escalating recklessness was no secret.

For months, they’d watched his behavior with growing unease. How he’d arrive at work disheveled, or sweating, even in the dead of winter. They wondered why a guy who was supposed to be checking boat registrations seemed so focused on tracking down illegal painkillers.

Raposo, the marine unit colleague who would later find Santos aboard the Little Tootie, was so concerned by Santos’ condition and rule-breaking style that he informed the unit�’s supervisor, Candido Trinidad, that he was no longer willing to back up Santos on calls.

But Trinidad — who’d become a kind of mentor to Santos — chastised Raposo and warned him against voicing such sentiments.

“Rumor spreading,” Trinidad wrote in a 2017 email, which was obtained by the Globe, “is a violation of our department policy.”

Trinidad did not respond to requests for comment.

A half-dozen current and former officers told the Globe they were aware of Santos’ pattern of questionable stops and vehicle searches. Several said the officer’s alleged drug robberies were so common that some officers jokingly referred to him as “El Pildoro” — The Pill.

This much is certain: By early 2018, in the months preceding the Little Tootie raid, complaints about Santos’ conduct had reached the highest levels of department leadership, according to records obtained by the Globe, as well as interviews with current and former officers.

Then-Deputy Chief Paul Oliveira, who oversaw a vast swath of the department, including internal affairs, had directly received at least four complaints about Santos.

One came from then-New Bedford Detective Bryan Oliveira — who is no relation to Paul — who said he approached the deputy chief around March 2018 with information that Santos was robbing motorists. The deputy chief seemed to show no interest.

“[Paul Oliveira] didn’t write anything down,” Bryan Oliveira said in an interview with the Globe. “He was sitting there, leaning back in his chair, looking at me like, ‘What do you want me to do about it?’”

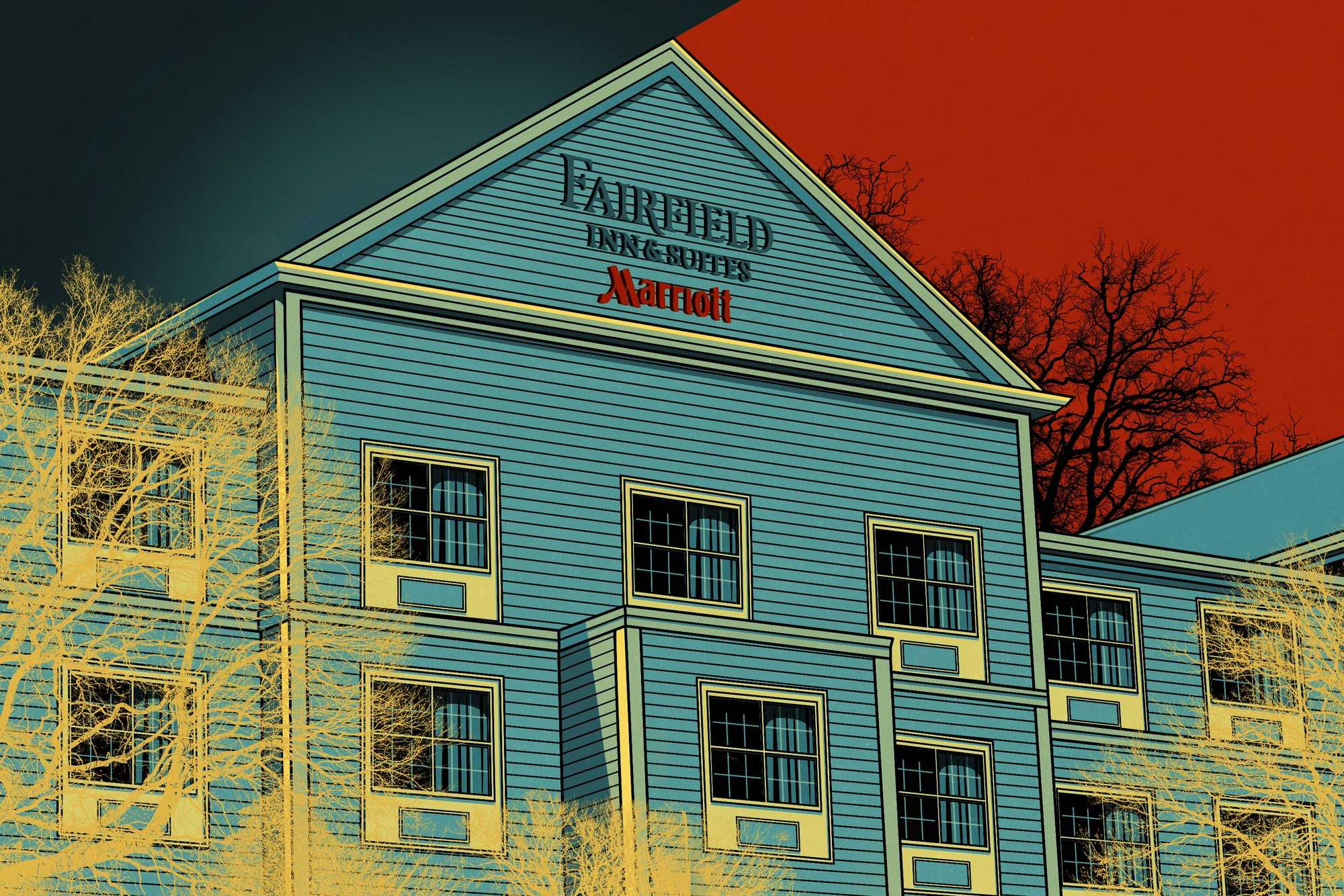

Complaints from guests staying at a Fairfield Inn near the New Bedford docks piled up around the time Officer Jorge Santos was active in the area. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

Around this same time, a security officer at a Fairfield Inn near the docks brought his own concerns to Deputy Chief Oliveira.

The security officer, Michael Roussel, who had retired as an officer in nearby Westport, told police he had first encountered Santos a year earlier, when he saw him conducting an illegal search of a hotel guest.

Roussel said he’d confronted Santos in the parking lot. Santos offered a strange response: The deputy chief wants me to do this, mentioning Paul Oliveira by name. Santos called Oliveira a “personal friend,” Roussel later told police.

Complaints from guests continued to pile up. Once, a man entered the hotel lobby and recounted a car stop, just 20 minutes earlier, in which an officer took pills from the vehicle’s passengers but allowed them to keep the cocaine and heroin in their possession.

Around May 2018, records show, Roussel reached out to Oliveira directly with his concerns. Oliveira, Roussel later told investigators, promised to look into it. Roussel told investigators he never heard back from Oliveira.

After the Little Tootie incident sparked an internal investigation, Oliveira wrote a memo documenting the complaints he had received in the months prior about Santos’ increasingly erratic — and illegal — behavior.

Oliveira did not respond to repeated requests for an interview. Holly Huntoon, a New Bedford police spokeswoman, did not directly address detailed questions sent by the Globe.

By June 2018, Santos was falling apart.

His once-prolific production was waning. In the preceding six months, records show, he had made just four drug arrests, two of them from the same incident. He was arriving at work disheveled and unshaven, several colleagues said. He started using the department-wide email system to hawk yard tools for cash.

On June 21, 2018, Santos’ shift ended at 4 p.m., police records show. But the general manager of the Fairfield Inn said Santos was stalking the hotel parking lot that afternoon, stopping at least two vehicles. It aligned with Santos’ pattern, which she and Roussel had detailed for police.

There was a flurry of other questionable activity that day. Santos called several “drug dealers” and “addicts,” according to an internal investigation.

Santos made or received seven phone calls to a man who would later be charged with trafficking illegal painkillers. He called a “pill addict and fishermen,” as well as a “pill addict and dealer,” investigators wrote in a report. Santos also called police dispatch, seeking the phone number of a man with a lengthy criminal history.

By then, Santos’ instability was obvious to anyone who bothered to look.

To his colleagues, who for months had witnessed his increasingly erratic behavior.

To department leaders, who had been fielding an escalating series of complaints about the officer.

But nothing was done. Jorge Santos was a star. Jorge Santos generated stats. Jorge Santos supposedly had informants.

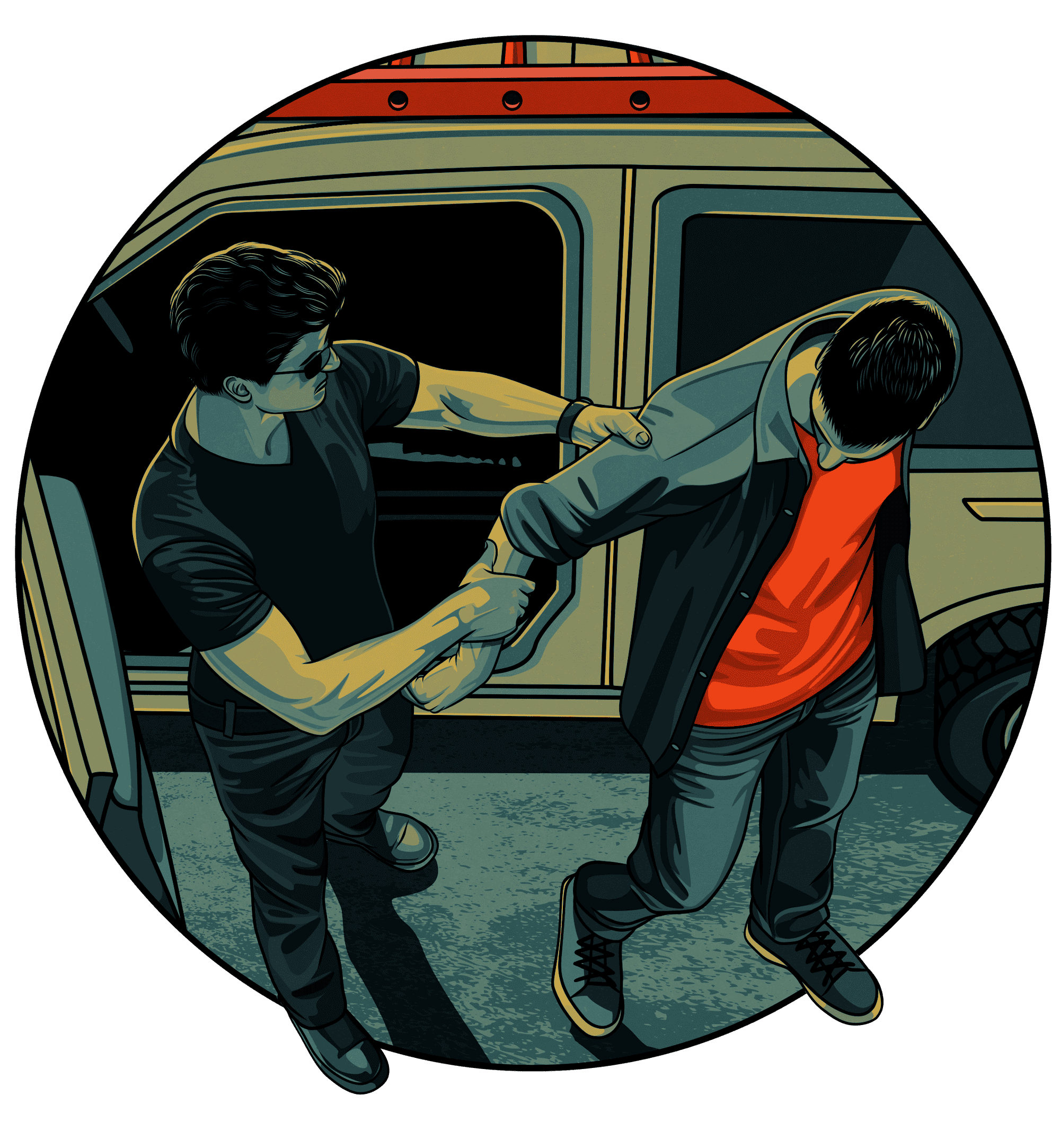

At 9:20 that night, hours after his shift ended, Santos parked his gold Jeep Commander and made his way in darkness towards the Little Tootie. He boarded the boat, forced his way inside, and chaos ensued.

Raposo showed up, quickly appraised the scene and hustled Santos off the boat. He told the fishermen to lock up and lay low.

Minutes later, 30 miles west of the city, Loya, captain of the Little Tootie, pointed his pickup east and pressed the gas.

He’d just dropped off a friend at the Amtrak station in Providence when a crew member called. The crew member said a man pushed his way into the Little Tootie’s cabin and was demanding drugs.

Pastillas, Loya figured.

Captain Freddy Loya stood on a scallop boat docked in the Small Boat Harbor in Newport News, Va. Loya was captain of the Little Tootie, another scalloper, when a New Bedford police Officer Jorge Santos boarded it, threatened the crew, and searched for drugs. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

Nearing 50, Loya was a pillar of the local fishing community, one of four Loya brothers captaining fishing vessels up and down the Eastern Seaboard. He grew up working his father’s shrimp boats in the Gulf of Mexico. Now, his own boat was under siege.

In his head, he replayed his own interactions with Santos. The stops, the demands for drugs, the theft of pills, and the push to become an informant.

Loya remembered how fishermen had fantasized about taking revenge. As he sped back toward New Bedford and the Little Tootie, Loya pounded the steering wheel, exuberant.

I got you!

Over the next few hours, Santos made a series of frantic phone calls and fired off texts.

At some point, he managed to rouse Trinidad, his former supervisor and mentor. Surveillance footage showed both men entering Trinidad’s office around 5:30 a.m.

They’d remain in there for the next two hours.

Officer Jorge Santos' version of the Little Tootie incident changed significantly in the hours after it occurred. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

When the pair emerged, Santos offered an entirely different version of the previous night’s events than the one he’d shared with Raposo and a supervisor just hours earlier.

He’d been at home the night before, he wrote in a report, when a “contact/concerned citizen” had phoned with a tip. It was big: a hundred grams of opiates aboard a scalloping boat.

Santos hurried over. On his way, he said, he’d tried — unsuccessfully — to reach a supervisor. At the boat, a crew member welcomed him aboard. Below deck, he said, he’d found a crewmember sprawled on a bed. Fearing the man was overdosing, Santos tried to revive him.

This new narrative, with Santos as hero, would crumble in the days and weeks ahead.

Members of the Little Tootie crew maintained that the wild-eyed officer from the docks had barged onto their boat, assaulted a sleeping fisherman, and demanded drugs, while muttering about a confidential informant.

Then internal investigators heard from more fishermen who came forward and shared stories about “Pastillas.” They told of illegal vehicle searches that stretched an hour; of pills that disappeared between seizure and the evidence locker; of bold drug robberies.

Stories identical, in other words, to those department leaders had been hearing for months.

Then-Chief Joseph Cordeiro told the Globe in a recent interview that he suspected Santos had “some kind of dependency” on pills and ordered him to take a drug test. Santos passed.

And what of Santos’ supposed snitch?

There wasn’t one — at least not by any reasonable definition.

There’s no evidence that the officer known for squeezing everyone on the docks had any registered informants; several current and former officers said there was no reason for officers on the marine unit to cultivate informants.

The Globe requested records showing how many informants the New Bedford Police Department has registered, and the department refused to provide them. Internal investigators would eventually find that Santos had violated departmental policy on CIs, though they did not specify how.

Raposo, who’d been first on the scene that night, told internal investigators who later reviewed the incident that Santos had initially pointed out a man boarding the Little Tootie, identified him as the boat’s captain and claimed he was his source. (The captain, Loya, was in Rhode Island at the time.)

Kelly Botelho, a New Bedford sergeant who also responded to the Little Tootie call, later reported that, on that night, he’d briefly met a man Santos identified as his informant, on a pier not far from the Little Tootie. But Botelho’s memo to the chief made no mention of an informant, and when questioned later by internal affairs about the discrepancy, Botelho struggled to explain why he’d left it out.

Santos’ supervisor, Trinidad, also told an implausible story to internal investigators.

Just a day after his early-morning huddle with Santos, he said, he’d been driving through New Bedford when he conducted a traffic stop. Trinidad claimed the driver mentioned that he worked as an informant for Santos. Trinidad told Oliveira, the deputy chief, that the man might prove useful in the internal investigation of Santos.

The Little Tootie, shown here in its home port of Newport News, Va., was the site of an alleged drug shakedown orchestrated by Officer Jorge Santos in New Bedford in 2018. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

Later, investigators would determine that this latest purported informant, a local man with an extensive criminal history, was a friend of Santos’. The two men drank together and shared meals. They hung out at the informant’s home at least once.

When internal investigators managed to question the purported informant, the man was cagey, records show. He claimed he had tipped Santos off about drugs on the Little Tootie, but also denied some of Santos’ other claims.

Pressed by internal investigators, the man acknowledged Santos had warned him that investigators would be contacting him. He said the two had spoken “two or three” times since the Little Tootie incident.

Police documents reviewed by the Globe cited 57 calls between the two in the days following the incident.

Accompanied by an attorney, Santos twice sat for interviews with internal affairs investigators. He repeatedly claimed he was unable to recall pertinent details. Several times, including when asked specifically about how he’d come by information about drugs on the Little Tootie, he invoked his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

Advertisement

As internal investigators worked their investigation into Santos, the Bristol district attorney’s office embarked on one of its own. A grand jury met in 2019. A flurry of subpoenas went out, including to Raposo.

The officer was leery.

For more than a year, Raposo had lodged complaint after complaint about Santos — to his unit supervisor, to the deputy chief, to internal affairs — only to see them ignored.

Worse, in some corners of the department, there were murmurs that Santos had been unfairly maligned. On multiple occasions, Raposo said, he was angrily confronted by colleagues who accused him of railroading a fellow officer.

Before agreeing to testify now, Raposo wanted assurances the case was being taken seriously.

Where is this gonna go? Raposo recalled asking Bristol County prosecutor Patrick Driscoll, who was involved in the grand jury probe.

We’re gonna go wherever the evidence takes us, Driscoll assured him.

Eventually, Raposo came around. He said he put on a jacket and tie and answered question after question from Driscoll — about his complaints to Trinidad, about when he’d warned the deputy chief about Jorge Santos.

In time, he said, he even came to view the grand jury proceedings as an opportunity, if not for justice, then at least vindication.

Still, he harbored no illusions about the implications of testifying against a fellow cop — especially one he knew to be volatile.

As the grand jury proceedings progressed, and an expected indictment neared, Raposo made plans to send his wife and kids to stay with his in-laws. He feared for their safety, believing Santos might come after him for breaking the supposed blue wall of silence.

Prosecutors from the Bristol district attorney's office had a grand jury investigate the allegations against Santos. The inquiry ended without charges. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

The district attorney’s probe seemed to be moving along, blessed with an embarrassment of evidentiary riches.

Alleged victims of the officer testified. An array of other evidence included phone records, Santos’ own comments, Raposo’s testimony.

The department’s own 240-page internal affairs report found that for roughly two years, Santos had turned the New Bedford waterfront into his own personal pharmacy. Calling Santos’ behavior “shocking to the conscience,” investigators cited evidence showing that the officer had systematically preyed upon some of the city’s most vulnerable citizens, “violating their constitutional rights [and] concealing his behavior through police work.”

In all, internal investigators found that Santos had violated 25 policies. Oliveira disagreed with only one finding.

The report didn’t address whether Santos fabricated informants, though it said he violated departmental policies governing informants.

Then, abruptly, the show was over.

On Dec. 20, 2019, prosecutor Patrick Bomberg wrote to Cordeiro, the police chief, and said the criminal investigation was being closed without charges.

No further explanation was offered to anyone, including not to Santos’ alleged victims, some of whom had traveled from across the country to appear before the grand jury. And not to Raposo, who learned of the decision only after he asked about it.

It was a stunning outcome, one that Raposo hadn’t imagined.

Still, he figured, there would be some penalties. Santos would most certainly face a raft of administrative charges, at least enough to push him out of the department.

Again, Raposo was wrong.

Santos was still employed — on paid, administrative leave — in July 2019, more than a year after the Little Tootie incident, when he finally went too far, even for the New Bedford Police Department.

It began as a fender bender. Security footage showed another car bumped into Santos’ vehicle. In response, Santos jumped out and yanked the other motorist from his car.

(J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

By chance, a rookie New Bedford officer was nearby. Santos demanded his handcuffs, then cuffed the motorist, dragged him away, and held him until other police reached the scene.

A State Police investigation followed. Authorities charged Santos with assault and battery and a civil rights violation.

In late January 2020, 19 months after New Bedford Police placed Santos on paid leave, the department took initial steps to terminate Santos. The mayor set a hearing date for the matter. Within weeks, Santos resigned.

Santos’ departure was without any fanfare or attention. It was a final gift from a department – and a city – that had for so long protected him.

Santos has never spoken publicly about his actions. When Spotlight reporters found him at the Florida home where he now lives, he declined to comment.

If the saga of Jorge Santos sparked a single reform within the department, or a scintilla of soul-searching, there is no evidence of it.

New Bedford police issued no new guidance on the use of informants. There was no attempt to address the concerns raised by internal affairs investigators about illegal stops, questionable searches, and supposed thefts. Even as the extent of Santos’ misconduct came into focus, supervisors struggled to condemn an officer who, for so long, had made them look so good.

As the department moved on, things quickly deteriorated for Mark Raposo.

Higher-ups shifted his schedule and changed his job duties, which pushed him back to patrol — his dream job gone. It was impossible for Raposo to see the move as anything but retribution for airing the department’s dirty laundry.

He stewed about it and then, one day in 2020, he picked up the phone and dialed the FBI.

As Raposo tells it, an agent from the bureau’s Lakeville office listened as he laid out Santos’ alleged crimes, and the lack of accountability that followed. Raposo told them about the vehicle stops, the illegal searches, and more. And he talked about how he’d taken it as far as he possibly could — all the way to New Bedford’s deputy chief, Paul Oliveira.

Unbeknownst to Raposo, that was a name the bureau knew well.

Like Santos, Oliveira had once been a young department star. Like Santos, Oliveira was brash and swaggering, and known for racking up arrests at an eye-popping pace. And like Santos, he was trailed by a near-constant stream of allegations, whispers that had eventually coalesced into an FBI probe.

An FBI spokesperson said the bureau “cannot confirm or deny the existence of investigations.”

Oliveira built his success on the backs of confidential informants. The difference between him and Santos was that he actually recruited a stable of registered informants — cultivating them, squeezing them, and building a playbook that would be utilized for decades to come. Santos and others tried to follow it.

Oliveira’s success propelled him up the ranks.

Now in his mid-50s, he can be found most days behind a desk in the corner office of a squat brick building on Rockdale Avenue, an American flag hanging in the corner.

He is New Bedford’s police chief.

Spotlight editor Brendan McCarthy contributed to this report.

Feedback and tips can be sent to the Boston Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected], or by calling 617-929-7483. Mail can be sent to Spotlight Team, the Boston Globe, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

This story has been updated to reflect that the Quincy Police Department, one of the state’s largest departments, recently adopted an informant policy. The agency had previously released records to the Globe that showed it had no policy.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporters: Dugan Arnett, Andrew Ryan

- Editors: Brendan McCarthy, Gordon Russell, Mark Morrow, Kristin Nelson

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Kirkland An

- Illustrations: J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe

- Photographer: Lane Turner

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Ronke Idowu Reeves, Adria Watson, Diamond Naga Siu, Amanda Kaufman

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Legal review: Jon Albano

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC