The FBI investigated him for stealing from drug dealers and misusing informants. Now he’s the police chief.

New Bedford Mayor Jon Mitchell gathered civic leaders and reporters for a major announcement one afternoon in June 2021.

A decade into his tenure, Mitchell, a former federal prosecutor who once led the task force that tracked down the fugitive gangster Whitey Bulger, had chosen the city’s next police chief, the man who would lead one of the state’s largest police departments.

His pick?

Paul Oliveira.

“This is an auspicious occasion, because I’ve known this individual for a long time, and I’m fully confident that he is up to this job,” Mitchell told the crowd.

The two had worked cases together years earlier, when Mitchell was a young prosecutor in the US attorney’s office in Boston and Oliveira was climbing the ranks of New Bedford’s Police Department.

Oliveira stood beside the mayor that afternoon, stoic. Like the rest of the nation, New Bedford was grappling with the racial reckoning in law enforcement that followed the George Floyd murder. But the city was on an upswing and crime statistics were down significantly.

“Policing has changed dramatically throughout the careers of those of us standing here,” Oliveira, then 51, said. “I believe that those experiences — good and bad — will now fuel us forward through the next chapter of police reform.”

Nearly a quarter century had passed since Oliveira rose to local prominence, orchestrating what was then the largest drug bust in city history. Since, his hair had thinned, his tanned features softened. But he still looked like he could lead a team of detectives through a drug-house door.

“If somebody would have told me 20 years ago that I’d be police chief,” it would’ve been “crazy,” he said in an interview not long after his appointment. “But, you know, that’s life, right?”

Paul Oliveira looked on as Mayor Jon Mitchell announced he would be New Bedford Police Department's new chief at a press conference in June 2021. (Peter Pereira/The Standard-Times /USA Today Network)

Oliveira wasn’t the only one who seemed surprised by his promotion. Others who had worked alongside him, served him as informants, or been arrested by him were confounded.

They sent texts or chatted, but only among one another: This guy? Does the FBI know? But what about ...

Despite their shock — and in some instances, anger — they kept their concerns buried. No one spoke out in that moment or the years since — at least not publicly.

In New Bedford, they know things often don’t end well for snitches.

New Bedford routinely ranks as the most lucrative commercial fishing port in the nation. (J.D. Paulsen For the Boston Globe)

No one is more familiar with the inner workings of the New Bedford Police Department than Paul Oliveira. In the decade before his ascension to chief, he’d overseen the department’s Professional Standards unit, known as internal affairs, which investigates allegations of police misconduct. After that, he served as deputy chief, a role in which he signed off on internal investigations of corruption or misconduct.

Oliveira understands the issues and problems in the department because over much of the last 30 years he has done his best to turn a blind eye to them, a Spotlight Team investigation found.

New Bedford officers have slept with informants, lied in search warrants about the information they’ve provided, and encouraged them to buy drugs for personal use.

Among other abuses: One informant alleged a New Bedford officer alerted a member of the informant’s gang that he was working for police. Internal investigators did not sustain the charge but determined the officer had leaked sensitive information to the gang member, an old friend. Three other informants told the Spotlight Team that officers casually revealed to them the identities of other people working for police, a dangerous breach in protocol.

Yet Oliveira has exercised a light touch when it comes to holding wayward officers to account. He’s also shown little interest in making reforms to departmental policy even in the face of abuses.

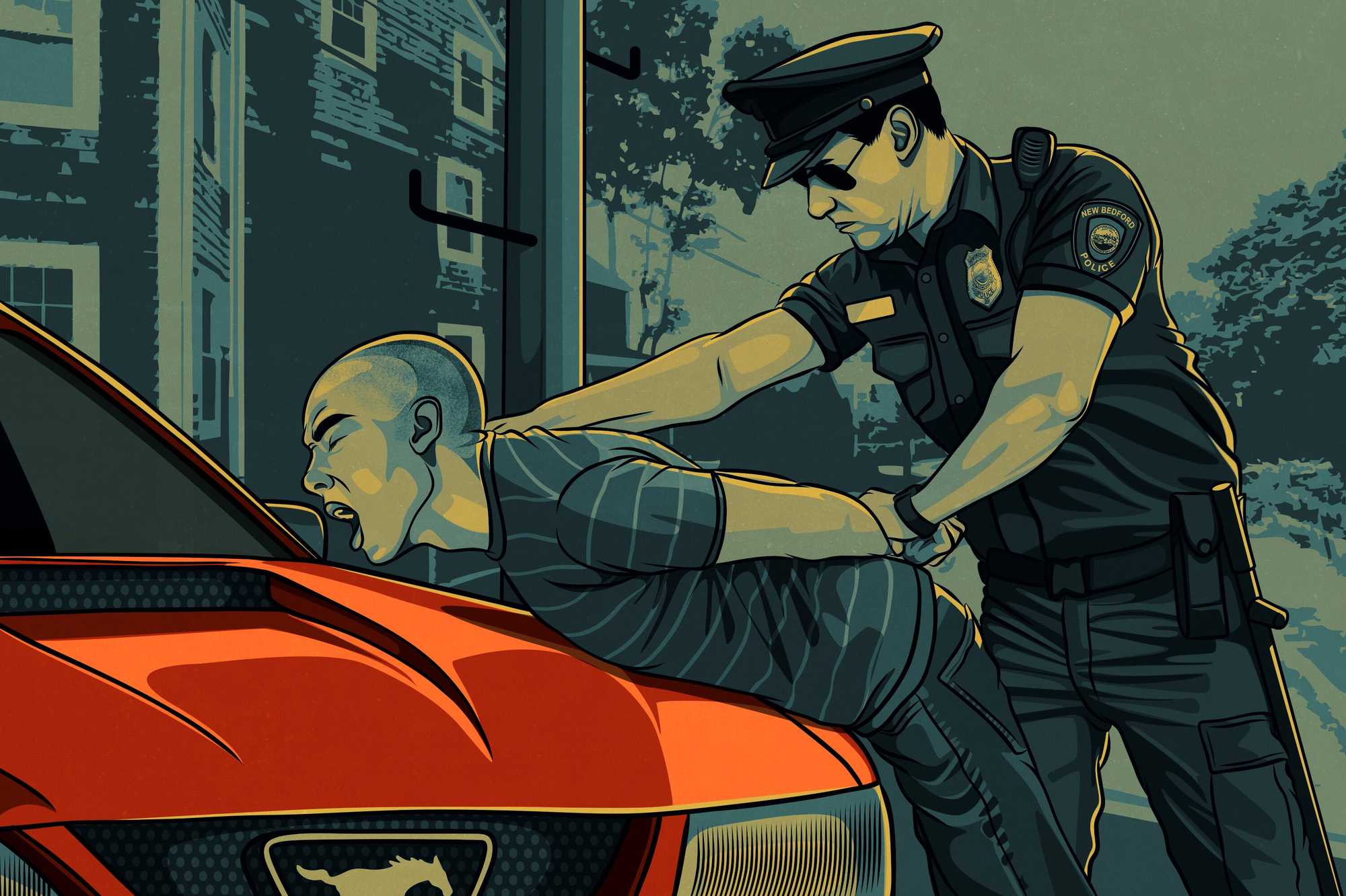

The Globe commissioned illustrations of key events for this series. In order to avoid identifying certain sources, we chose not to depict specific individuals. Illustrations are instead an artist’s rendering of events, people, and concepts.

Over the last three decades, the FBI has investigated Oliveira himself in at least three probes into alleged informant-related misconduct, the Spotlight Team has found.

One inquiry centered on allegations of corruption within the narcotics unit, around 1999, when Oliveira was a star drug detective. A retired FBI agent confirms a target of the probe was Oliveira.

Years later, around 2017, Oliveira’s former drug unit colleague was questioned by an agent from the FBI’s public corruption unit about Oliveira’s history with informants and narcotics cases.

And another former New Bedford detective told the Spotlight Team he was approached by an FBI agent in 2022 and asked about Oliveira and the department’s trustworthiness on drug investigations.

A New Bedford Police Department marine unit boat. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

Oliveira did not respond to repeated requests for an interview. Holly Huntoon, a New Bedford police spokeswoman, did not directly address detailed questions sent by the Globe.

Oliveira has never been charged with a crime or disciplined by the department. But under his watch — first as deputy chief and later as head of the department — New Bedford police have abused the confidential informant system in almost every way imaginable. And they’ve rarely been disciplined for it.

The list of errant officers includes Detective Jean Lopez, who in 2022 was excoriated by a Bristol County judge for falsely attributing information to a CI, a confidential informant. Lopez, in a brief interview with the Globe, called it a paperwork mistake.

Then there is Sasha Vicente, who as a narcotics detective in 2016 instructed an informant to skip court in order to perform a controlled drug buy, and to lie to a judge about why he missed court. She also encouraged him to purchase drugs for personal use, according to an internal investigation. Oliveira promoted her to sergeant in 2021. Two years later, she was accused of aiding a suspect fleeing a crime scene. Internal investigators found Vicente violated departmental regulations related to personal conduct and suspicious conduct, according to the New Bedford Light.

Listen to the podcast

In another case, in 2021, a Massachusetts state trooper overheard New Bedford Detective Samuel Algarin-Mojica providing sensitive information to an informant regarding a major drug investigation. An internal probe determined Algarin-Mojica broke numerous rules and “committed a very serious breach of confidentiality” that could have compromised a State Police wiretap. For reasons unclear, Oliveira disagreed with internal investigators and tossed the charges.

The list also includes Justin Kagan, the former head of New Bedford’s Organized Crime Intelligence Bureau, who as head of New Bedford’s Organized Crime Intelligence Bureau in 2019 oversaw the department’s highly sensitive informant registry system. Kagan, now a captain overseeing criminal investigations, admitted in 2023 that he falsified records to make it appear as though an informant had been registered with the department when she hadn’t been.

The New Bedford department has refused to provide the Globe with even basic information about how many informants police have registered, or how much they’ve been paid. Vicente, Algarin-Mojica, and Kagan did not respond to requests for comment, and the department ignored interview requests.

And there is Jorge Santos. Oliveira brushed off repeated complaints that the officer stalked the waterfront, conducting repeated illegal searches and seizures, preying on Hispanic fishermen, and violating the rights of countless people. Evidence collected by internal affairs also suggested Santos fabricated an informant as pretext for the attempted robbery of a fishing boat.

Advertisement

Though Oliveira approved a report that found 24 departmental infractions in connection with the boat incident, Santos was never disciplined. While on leave over that incident, he assaulted a motorist, leading to criminal charges. He resigned after 20 months of paid leave, before any administrative discipline was imposed.

Perhaps the most extraordinary case of informant-related misconduct was revealed in a 2023 Globe investigation, nearly two years into Oliveira’s tenure as chief. The Globe report detailed how Detective Jared Lucas advised federal agents in 2016 that a reliable confidential informant had tipped him off to a drug network moving kilos of heroin through the city.

In response, investigators from New Bedford and other local, state, and federal agencies mobilized, building a yearlong case dubbed “Operation High Stakes.” Lucas helped carry out surveillance, transcribed wiretapped calls, and appeared for the dramatic arrest of the supposed kingpin.

A New Bedford police officer making an arrest. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

What Lucas had failed to mention throughout — and what emerged only years later in the Globe — was that he was having a sexual relationship with the informant in the case, who happened to be the fiancée of the alleged drug kingpin. Evidence shows Lucas had also targeted a second romantic rival of his lover/informant, the focus of an unrelated trafficking case.

The Globe report led to the unraveling of that case. And it has threatened at least one more case, raising a slew of questions about what other abuses have been allowed to fester under the secrecy of a deeply flawed informant system.

The answer? A lot.

“It’s Whitey Bulger without the bodies,” one former narcotics detective told the Globe, comparing the rampant abuse of informants in the city to the FBI’s protection of Boston’s notorious gangster, who was secretly working as a snitch. “The only difference [here] … was people weren’t getting whacked for it.”

The underpinnings of how this all came to be — how the New Bedford Police Department became the poster child for informant-related abuses, how officers were continually allowed to push the boundaries and break the law — goes back more than a quarter-century.

To the 1990s, and America’s drug war.

To one narcotics detective whose success set the standard for what the department considered “good, hard police work.”

On the streets, they called him Robocop.

His badge read: Oliveira.

Advertisement

New Bedford was a battleground of drug trafficking before the turn of the century.

Drugs coursed through the city: at the port, where “dirty boats” were known to bring in after-dark, off-the-books shipments; in the city’s peeling housing projects, where toddlers played alongside discarded crack vials; and inside the motorcycle clubs and seedy waterfront bars, where cash-flush fishermen gathered to blow off steam.

Cocaine in corner-cut sandwich bags. Powdered heroin nestled in parchment paper. Marijuana bundled into bricks.

Law enforcement’s efforts had been gaining steam since President Nixon in 1971 declared drugs “Public Enemy No. 1” and a scourge requiring an “all-out offensive.”

Scenes from New Bedford. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

In turn, the country’s criminal justice apparatus weighed a number of tough responses: reinstituting the death penalty; rounding offenders up and shipping them to an island. One congressman proposed simply beheading them.

In 1986, the country’s drug offensive reached a new level. Two days after being drafted by the Boston Celtics, former University of Maryland star Len Bias died after a night of heavy cocaine use.

US Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill, a snow-haired Democrat from Cambridge, seized on Bias’s death, shepherding through the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. The law set mandatory minimum sentencing for even nonviolent drug offenses.

Lawmakers went further two years later with the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, which provided — in the words of then-President Reagan — “a new sword and shield” for police.

These bills launched a new kind of drug warrior onto the streets — aggressive, well-resourced, and empowered to root out drugs by almost any means necessary.

Victories in this all-out effort to dismantle major drug operations put a higher premium than ever on inside information — eyes and ears on the hidden operations.

Informants had always maintained a place in law enforcement; federal moles had helped chip away at organized crime for decades, while jailhouse snitches had long mastered the thorny quid-pro-quo of swapping tips for reduced sentences.

The Ash Street Jail in New Bedford. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

But as the drug war intensified, police use of street-level informants exploded. In 1995, the National Law Journal analyzed federal search warrants in Boston and three other American cities, finding that over a 13-year-period, the share of warrants citing informants doubled, to 92 percent.

Unlike other undercover work, which could be costly, risky, and time-consuming, informants were cheap, quick, and — thanks to ever-harsher penalties for even minor drug offenses — increasingly motivated to cooperate.

They also came with another benefit: Because some informants risked violent retaliation if discovered, police were granted an unprecedented level of secrecy in handling them.

Simply by citing an ambiguous safety concern, a drug detective could ensure that an informant’s identity would remain forever shielded from judges, attorneys, and defendants.

“It didn’t take officers very long to realize,” said Dennis Kenney, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, “that nobody’s ever going to call them on a confidential informant.”

(J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

In New Bedford, like most cities, the drug cops were considered rock stars.

They roamed the streets in late-model Ford Broncos seized from local drug dealers. They posed next to tables stacked high with confiscated dope, their exploits celebrated in newspaper stories.

Plainclothes, undercover, and unburdened by the minutiae of patrol work, they had a single objective: Make cases. Get drugs.

And in 1990s New Bedford, when it came to tracking down drugs, Paul Oliveira was “a god,” former colleagues said.

He was charming and polished, with a criminal justice degree from the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth when cops with such credentials were still rare. Even those who found his confidence off-putting acknowledged that cops didn’t come much smarter.

Weld Square in New Bedford, where Paul Oliveira, now the city's police chief, worked the overnight shift early in his career. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

As a young patrolman, he’d been assigned to the overnight shift in the Weld Square neighborhood, an area plagued by drugs and prostitution. There, he pressed sex workers for information, chased down tips, and disrupted the drug trade enough to capture his bosses’ attention.

In 1996, after just three years on patrol, Oliveira was tapped for the department’s vaunted drug unit.

“I wanted him,” Mel Wotton, then the lieutenant in charge of the unit, told the Globe. “He was the cock of the walk.”

Oliveira’s gift, current and former colleagues said, was his mind. In a unit full of bruisers, Oliveira was a thinker. He’d disappear for hours at a time, then re-emerge with new information and a fresh target.

New Bedford has been a hotspot in America's war on drugs. (J.D. Paulsen for The Boston Globe)

And he never seemed to miss.

It wasn’t just that he could predict where drugs were going to be; he seemed to know exactly how much would be seized, sometimes down to the gram.

“He was like Babe Ruth calling his shot,” said one former drug unit colleague.

With each bust, Oliveira’s legend grew. So too did the jealousy of his peers. They wondered how he did it.

“Good searching and a lot of luck,” Oliveira told the Globe in 1998, after leading a raid that resulted in the seizure of $50,000 worth of cocaine.

And for a long time, as the drug seizures piled up, that explanation seemed to suffice.

“I think he was probably working in the unit for a couple of years,” said a former New Bedford police lieutenant, “before anyone ever questioned how he pulled all this off.”

Get Snitch City in your inbox

Sign up to receive Spotlight reports and special projects, like Snitch City

The two-family house at 45 Jones St. didn’t look like much: decorative stone facade, yellow siding, out by the city’s airport. But among local law enforcement, it was notorious — a suspected drug house whose occupants, through no lack of effort from local police, had long eluded arrest. Even the Drug Enforcement Administration had been unable to get inside the drug network, and their home.

So Robert “Bobby” Richard, a former drug unit officer, was shocked when Oliveira gathered members of the New Bedford narcotics unit for a pre-raid briefing on Dec. 17, 1997, and identified their target of the day.

Jones Street was the site of a major drug bust by New Bedford police in 1997. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

“I remember being like, ‘Holy Christ — this place,’” said Richard, then in his second year with the drug unit.

Richard and Oliveira were friendly. They’d joined the department the same year, been promoted to the drug unit on the same day. Oliveira would sometimes recruit Richard for raids that could net lucrative overtime pay.

Later, the two would have a falling out, Richard said; during his time with internal affairs, Oliveira twice investigated Richard — first as part of a domestic assault case and, later, for smoking tobacco on duty and several other minor infractions, which resulted in Richard’s termination.

The bust that day in 1997, Richard recalled, proved to be fairly run-of-the-mill. Following an hours-long search, detectives recovered a few thousand dollars in cash and more than half a kilo of cocaine, a substantial, if not spectacular, seizure. They arrested a 40-year-old Colombian national who went by “Flaco.”

The next morning, however, Richard arrived at the department’s headquarters to find the parking lot filled with television news trucks.

What’s going on? he asked.

Paul got four kilos last night, came the reply.

That was a record for New Bedford police.

Perplexed, Richard pulled Oliveira aside. The story Oliveira told him, Richard recalled, was different from the one police officials told publicly.

The officers, Richard included, had left the house with much less coke than the ultimate haul. But Oliveira told Richard that the informant in the case later returned to the home, retrieved additional drugs the detectives had missed, and left them in the woods near the home. And then he tipped Oliveira off to the location of the stash.

Oliveira went back, picked up the drugs, and added them to the overall haul, according to Richard, who said he was repeatedly briefed by Oliveira. For his troubles, Richard said, the informant was allowed by Oliveira to keep a kilo, with a street value of about $40,000, for himself.

(J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

Richard didn’t consider himself a saint. He knew policing — and informants, in particular — sometimes required navigating gray areas.

But this was on another level.

Standing in the station that day, listening as the chief bragged to the press about the “good, hard police work” by Oliveira and the others that led to the historic seizure, Richard was floored.

“Biggest bust in the history of the New Bedford Police Department,” he said recently, “and it was all [expletive] bull[expletive].”

Of the dozen or so members of the New Bedford drug unit, none had more — or better — informants than Oliveira, according to Richard and three other detectives who worked with Oliveira in narcotics, all of the others speaking with the Globe on the condition of anonymity.

Oliveira often worked alone. Few knew the names of his informants and the department had no policy governing their use. Then, like now, the process was so secret that even the detectives carrying out the raids were typically unaware of the identity of the informant who’d helped set it up. In court, detectives merely needed to say they had a reliable confidential informant whose information set the events in motion, a claim that is rarely challenged.

A pedestrian on Elm Street walked in the gathering dark of downtown New Bedford. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

Not that Oliveira didn’t draw scrutiny. In 1998, department records show, he was investigated by internal affairs after a mother reported that Oliveira was providing her daughter with drugs in exchange for information. He was eventually cleared.

In time, colleagues began to understand Oliveira’s tactics. His specialty was the so-called “set-up” case, according to three colleagues who worked with him in the drug unit, as well as two people who later investigated him and a former informant of Oliveira’s.

In a series of interviews with the Spotlight Team, the former informant outlined his work, sharing details of drug raids that reporters independently confirmed through police and court records. The broad strokes of the informant’s story mirrored what Oliveira’s former colleagues described.

In drug work, the objective is to move up the food chain: flip a user for a dealer, a dealer for a supplier.

But Oliveira, they said, often worked in the other direction.

His stable of informants, according to his former colleagues, included high- and mid-level city dealers. At Oliveira’s behest, these informants would set up smaller drug deals in exchange for the freedom to operate unencumbered, the former colleagues said.

After facilitating these lower-level deals, the informants would alert Oliveira, who would make the busts, sometimes within hours.

“The dealer brings the drugs to the house — it’s put in the safe; Hold this for me — [then] he goes back to Paul and tells him it’s good to go — there’s 250 grams of cocaine in the house,” Richard said.

“You time the search warrant, you raid the house a few hours later, and it’s boom, success,” he added. “Over and over and over.”

New Bedford police execute a search warrant. (J.D. Paulsen For the Boston Globe)

“We didn’t really know which informants were doing which cases,” said another former narcotics detective. “But it was pretty easy to figure out.”

Once the informant dropped off the drugs, the raid went down.

According to the former officers, these dealers were deemed, per Oliveira, “on the team” and thus immune to arrest.

“We used to call it a ‘license to deal,’” said Richard.

The former Oliveira informant told the Spotlight Team it was an extraordinary license.

On several occasions in the late 1990s, the informant said, he worked with Oliveira to set up lower-level dealers. In exchange, he was allowed to sell drugs without fear.

Advertisement

The informant confirmed much of what the former officers detailed: Working with Oliveira, the informant would arrange to sell smaller amounts of drugs to others in his orbit. Before, or immediately after the sale, the informant would alert Oliveira and soon after, Oliveira and others would swoop in.

Despite what later showed up in court records — descriptions of lengthy surveillance and shoe-leather police work — the informant said the cases were typically pulled together in mere hours.

“They were looking for trafficking cases, at a minimum,” the informant said. “So, you know, you give somebody a half-ounce and [then tell Oliveira], ‘Here it is, and this is where they’re going with it.’”

The informant valued Oliveira’s protection.

“I was led to believe like ... short of murder, you could do whatever the [expletive] you want,” the informant said. “And you tell a young [person] with money and no moral compass that, you’re creating [expletive] animals, man. And that’s what I was.”

The informant estimated his set-up cases led to more than “100 years” of collective jail and prison time for others.

Union Street leads to the New Bedford waterfront. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

Wotton, a now-retired lieutenant who ran the New Bedford narcotics unit in the 1990s, defended the integrity of the unit.

“There was a lot of checks and balances,” he said in a recent interview. “We tried to build that unit on honesty, integrity, and rule of law.”

“There’s always a way to abuse the system,” he added. “Can I say 100 percent it never happened? No. But I think that we had a pretty good record and we kept it in line.”

Wotton denied that informants were given a “license to deal.”

In an interview months earlier, he was less authoritative. “I’d be remiss to say that it never happened,” he said. “But I never saw it.”

There were reasons not to look too closely.

In addition to clout and prestige, big busts brought paydays. Narcotics detectives could nearly double their salaries with overtime and court pay. What’s more, civil forfeiture laws had become lucrative for police departments; if authorities could show seized money or vehicles had been used in drug activity, they could be appropriated.

Still, as the ‘90s drew to a close, the pattern of misconduct in the unit was becoming difficult to ignore.

In 1997, an outside audit of the department found that more than 20 percent of New Bedford officers believed their colleagues were stealing drugs or money from local dealers.

Two years later, New Bedford police Officer Stephen Greany was arrested, and later convicted, for selling the identity of an undercover State Police trooper to a local cocaine dealer.

Not long after, three members of the DEA’s New Bedford office who regularly worked with New Bedford police sounded the loudest alarm yet on what they described as astonishing abuses of the CI system.

The situation in New Bedford had grown so dire, and veered so far from the norm, that the city was on the doorstep, one agent warned, of another “Whitey Bulger incident.”

By then, however, other federal investigators were already paying attention.

From his seat in a downtown Boston conference room, Arlindo Dos Santos sized up the panoply of law enforcement agencies around him. US attorney’s office. Internal Revenue Service. Massachusetts State Police.

A jovial, smooth-talking hustler, Dos Santos was a known quantity in New Bedford. His vast social circle included cops and criminals — and the distinction could be a fine one. When he’d first started selling marijuana at New Bedford’s vocational high school, Dos Santos told investigators, his drug supplier was a classmate who grew up to become a New Bedford narcotics cop.

On this day in August 1999, however, Dos Santos’ problems extended far beyond a few schoolyard dime bags. He’d been arrested on federal drug and money laundering charges for his role in a ring that allegedly pumped thousands of pounds of marijuana through the mail.

Facing the prospect of a lengthy prison sentence, Dos Santos had agreed to a proffer session, an arrangement in which defendants can swap information for leniency. This situation is typically, for defendants, a precursor to a plea deal.

But federal agents’ interest that day had little to do with his drug case, Dos Santos would later recount in a court filing. Instead, the feds wanted to know about corruption in the New Bedford Police Department’s drug unit.

One name came up again and again.

Paul Oliveira.

As it happened, Dos Santos had plenty to share. Oliveira and his supervisor in the drug unit, Wotton, were “gangsters,” Dos Santos said, “worse than me.” The pair maintained a so-called “green fund,” he told investigators: cash they’d pocket during raids. He offered names of dealers who had allegedly been ripped off by the pair.

Shortly after his proffer session, records show, Dos Santos also attended a meeting with the FBI. And he turned over a recorded conversation with Oliveira that he’d made at the FBI’s behest.

Dos Santos declined repeated requests from the Globe to comment. His account, however, is detailed in extensive sworn statements and matches the statement of another area drug dealer. The Globe also confirmed the account with two people familiar with the probe, including the lead investigator, now-retired FBI agent David Madigan.

The Spotlight Team identified five people who say they spoke directly with the FBI around this time about Oliveira and alleged corruption in the New Bedford narcotics unit. Another person said they were directly aware of the FBI probe, but never questioned.

One former member of the narcotics unit said he had a clandestine meeting with an FBI agent in the city’s Elm Street parking garage. The focus of their conversation: Oliveira and drug unit corruption.

Over the last three decades, the FBI has investigated Oliveira himself in at least three probes. (J.D. Paulsen For the Boston Globe)

“I didn’t tell them anything they didn’t already know,” he told the Globe. “The FBI knew all about this [expletive] guy.”

Oliveira was also under scrutiny for alleged obstruction of justice in the FBI probe into the narcotics unit.

John Martin, another New Bedford drug dealer cooperating with the FBI, told federal investigators that Oliveira had attempted to squeeze witnesses and interfere with the corruption investigation, according to federal affidavits and memos filed in court and obtained by the Globe.

“Martin stated that members of the [New Bedford] Narcotics Unit have been in his backyard, that [they] are constantly present around his store and are watching him constantly,” an investigator wrote in a summary of one conversation.

In an affidavit, Martin said Oliveira approached him directly, seeking the names of all the officers who were under scrutiny by federal investigators. Oliveira said Martin could get the names from Dos Santos, according to Martin. Martin declined repeated interview requests from the Globe.

Dos Santos later said in a sworn affidavit that federal agents, most notably prosecutor Michael D. Ricciuti, with whom Dos Santos was cooperating, were aware of the interference.

Dos Santos said his attorney was advised by Ricciuti that federal agents, while conducting surveillance, had watched New Bedford detectives follow Dos Santos to a local store, then had his truck towed. Another investigator in the case confirmed to the Globe that he’d been told by Ricciuti that New Bedford police were indeed interfering in the probe.

This was a remarkable allegation. If true, it meant not only that New Bedford detectives were actively impeding a federal investigation, but that the feds were aware of the interference and still didn’t pursue charges.

Ricciuti, now chief justice of the Massachusetts Superior Court, declined an interview request from the Globe.

In an interview, the lead FBI investigator, Madigan, confirmed that federal investigators believed Oliveira had interfered in the FBI probe.

“We heard Paul Oliveira went and talked to somebody,” Madigan said.

While the FBI was looking into the information provided by Dos Santos and Martin, another New Bedford drug dealer landed on their radar.

Frank “Rizzo” Simmons was a 25-year-old who sold drugs in New Bedford’s North End.

Simmons was arrested by Oliveira following an August 1998 raid of his Coffin Avenue apartment.

The apartment building at 214 Coffin Ave., where former drug dealer Frank Simmons once plied his trade. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

The apartment, Simmons admitted, had been stocked with cash and drugs: large amounts of marijuana, cocaine, and ecstasy. But during the raid, he said, he watched — handcuffed — as Oliveira and other members of the drug unit pocketed thousands of dollars in cash.

“Paul was passing out $1,000 stacks,” Simmons said in an interview with the Globe.

Simmons maintains there was $33,000 in the apartment that day, far more than the $2,230 Oliveira reported.

“And he turns to me,” Simmons recalled, “and he says, ‘That’s what we call the [expletive] green fund. Thanks, buddy!’”

The so-called “green fund” would appear repeatedly in court records and interviews, referenced by multiple drug dealers, as well as federal investigators.

One day, out on bail and awaiting trial, Simmons was summoned to his attorney’s office.

The FBI, he was told, wanted to talk.

During the ensuing call, Simmons told the Globe, an agent outlined a deal: In exchange for testifying against Oliveira and the New Bedford narcotics unit, Simmons said, the FBI offered to get his charges dismissed. They also offered up to $150,000 to relocate him.

The FBI wanted Simmons to snitch on Oliveira and the drug unit.

Reached independently by the Globe last year, Simmons’ attorney, Barry Wilson, corroborated his client’s assertions.

If convicted, Simmons faced a lengthy prison sentence. So the offer was an almost impossible stroke of good fortune, an opportunity not only to maintain his freedom, but to extract revenge on a detective he said stole $30,000 from him.

But the idea of cooperating with law enforcement, even against police, ran counter to his moral code, Simmons said. Snitching was snitching. And after consulting briefly with associates, he said, he declined the FBI’s deal.

“If I would’ve done that, as I explained to the feds, I would’ve had to look over my shoulder for the rest of my life,” he said in an interview.

So in 2001, Simmons swallowed hard and pleaded guilty to distribution charges. He was sentenced to two to four years in prison.

On the day of his sentencing, Simmons recalled, he was waiting in a holding cell inside New Bedford’s Superior Court, grappling with the implications of his decision, when Oliveira suddenly appeared.

As Simmons tells it, Oliveira approached his cell.

Former drug dealer Frank Simmons said that Paul Oliveira, then a narcotics officer, stopped by his cell in 2001 to thank him for deciding not to cooperate with the FBI. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

“He came in and said, ‘Thank you for doing the right thing,’” Simmons said.

And Simmons said he responded bluntly.

“I said, ‘Go [expletive] yourself.’”

Why, exactly, the FBI’s probe into Oliveira and the New Bedford narcotics unit fizzled remains a mystery. The FBI and the US attorney’s office declined to comment.

But Madigan, who’d worked the case for the FBI, believes Oliveira’s meddling played a role.

According to Madigan, Dos Santos and Martin suddenly cut off communication with the FBI not long after a series of interviews and proffer sessions, forcing the bureau to change tactics.

The FBI had been sketching out an undercover sting, aimed at collecting audio and video, of New Bedford narcotics cops in action. But amid the planning, New Bedford police announced an overhaul of their drug unit, which resulted in the transfer of Oliveira and others under scrutiny.

The department had been tipped off to the FBI’s efforts, Madigan said.

“Sometimes when you get all the pieces together — it takes too long, and you miss your opportunity,” Madigan said.

Seated in a diner outside New Bedford 25 years later, one former detective — the same one who’d spoken with an agent in the parking garage — said the failure to bring charges against Oliveira had huge consequences.

“For the life of me, I don’t know why the FBI didn’t run with the case,” said the former official, his coffee growing cold.

“Had they done their job back in the day, this department would be totally different.”

Change outside the department came quickly in the decades that followed.

The city’s drug trade – having once played out on street corners and in fast food parking lots – went digital, with deals made through cellphones and social media. The drugs changed, too. Prescription pain pills took prominence. New Bedford became one of the hardest hit communities in Massachusetts. Opioid overdoses skyrocketed. In 2023, for instance, opioid-related death rates in New Bedford were two-and-a-half times higher than in the state as a whole.

Through it all, federal investigators remained interested in Oliveira.

Two former New Bedford officers independently told the Spotlight Team they’ve been contacted in recent years by FBI agents and quizzed about him.

One of the inquiries is linked to federal skepticism about the New Bedford Police Department’s trustworthiness.

The opioid crisis has hit New Bedford especially hard. The rate of fatal overdoses here was two-and-a-half times that of Massachusetts as a whole in 2023. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

Bryan Oliveira, who is not related to the chief, previously served as the New Bedford police liaison to the Drug Enforcement Administration. He told the Globe that he was instructed by his DEA supervisors in 2018 not to share information about ongoing investigations with his New Bedford colleagues. He said he was told specifically to keep information from Paul Oliveira, then the deputy chief.

The order came after wiretapped phones in two active drug trafficking cases suddenly went silent, prompting FBI suspicions. Agents feared there was a leak, Bryan Oliveira said.

He told the Globe he was contacted by the FBI in 2022 and questioned about the wiretap in a high-profile Latin Kings gang case.

After two decades on the force, Bryan Oliveira had left in 2020 for a job in the Attleboro Police Department. Soon after, he sued the city of New Bedford and several members of its Police Department, alleging he faced discrimination and retaliation after a colleague outed him as gay. The case is pending.

Richard, Paul Oliveira’s former colleague, said he received a call from the FBI around the same time as Bryan Oliveira. It was the second time he’d heard from them.

About eight years ago, Richard met with an FBI agent seeking information about past misconduct in the department’s narcotics unit. The agent, assigned to public corruption, seemed interested in details, but concerned about the statute of limitations, Richard recalled.

“Former detective“For the life of me, I don’t know why the FBI didn’t run with the case.”

A few years later, around 2022, another agent reached out, Richard said.

The meeting was “about Paul Oliveira, specifically.”

Richard was forced out of the department in 2015 after an internal investigation sustained several allegations, including that he violated a state policy barring officers from smoking, that he failed to report two fender-benders, and other minor infractions. He said he shared with the FBI what he knew, including the same details he told the Globe.

After his conversations with the FBI, Richard said he expected action.

“I swear to God, I thought that the feds would pull up outside of his house one day and lock him up, and that would be it,” Richard said.

But weeks, then months, passed.

Then last July, came a different kind of announcement.

New Bedford’s mayor said he and Oliveira had agreed to a three-year contract extension, which would keep Oliveira atop the Police Department through at least 2027.

New Bedford Police Chief Paul Oliveira spoke during a press conference at City Hall discussing preparations New Bedford has taken to ensure a safe Election Day. (Peter Pereira/The Standard-Times /USA Today Network)

“Despite a decrease in police manpower, under Chief Oliveira’s leadership, violent crime in New Bedford has continued to decline with a 58 percent drop over the past decade,” Mitchell said in a news release. “Chief Oliveira has worked hard to build trust between the department and residents, which will set us up for still more improvement in public safety.”

Oliveira, meanwhile, thanked the mayor for his “steadfast trust in my leadership.”

But plans changed.

In mid-February, as the Globe began promoting this Spotlight investigation and podcast, Oliveira announced his retirement, effective May 3.

Oliveira didn’t give the reason for his departure, but in a released statement he thanked the community and the department for their support in fighting crime.

He specifically cited the narcotics division and its “brave, deeply committed” officers. “The officers there have relentlessly taken record numbers of drugs and guns off the streets, helping to make New Bedford a more desirable community to live in.”

When it comes to law enforcement’s use of informants, trust is paramount. Detectives need to trust their CIs. Informants need to trust their handlers. Judges and juries need to trust an officer when they say under oath that “a reliable confidential informant told me.”

The criminal justice system, on a whole, needs to trust police departments to play by the rules.

But New Bedford, one of the state’s largest law enforcement agencies, often doesn’t.

One night, around the same time Paul Oliveira was settling into his new post as chief, a teenager was pulled into the city’s West End police station and seated before a pair of detectives.

The teen had been caught with drugs during a traffic stop that evening. He was desperate to avoid jail time.

The detectives had an offer.

Help us out, they said, and we’ll take care of you.

The teen could not have known it then, but he was about to find out what it meant to be an informant for New Bedford police.

Andrew Ryan of the Globe staff and Spotlight editor Brendan McCarthy contributed to this report.

Feedback and tips can be sent to the Boston Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected], or by calling 617-929-7483. Mail can be sent to Spotlight Team, the Boston Globe, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

This story has been updated to include additional details about Robert Richard’s termination. The city provided records on March 17, after publication.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporters: Dugan Arnett, Andrew Ryan

- Editors: Brendan McCarthy, Gordon Russell, Mark Morrow, Kristin Nelson

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Kirkland An

- Illustrations: J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe

- Photographer: Lane Turner

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Ronke Idowu Reeves, Adria Watson, Diamond Naga Siu, Amanda Kaufman

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Legal review: Jon Albano

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC