‘Whatever they said, I would do it.’ Inside the shrinking world of one confidential informant.

He calls every few days, from a cramped cell inside a Massachusetts prison.

He talks about his past, his days playing football or basketball at the playground. He’ll talk about the present, the endless hours spent watching movies on his prison-issued tablet, the shortcomings of his New England Patriots. And often, he’ll muse about the future, picturing his final moments and how the payback might come.

The plunge of a knife? A savage beating?

Since the first death threat — just after moving to a new prison unit — he has accepted that he might not make it out alive. So he follows his own safety protocol of sorts: He won’t share his name with other inmates, is vague if asked about his hometown. Every night, without fail, he watches as the prison’s new arrivals are marched through his unit.

He studies faces: Whom does he recognize? Who might recognize him? Who could know about the label he bears?

Snitch. Rat. Informant.

This nightly ritual of survival stems from a decision he made several years ago, in the back of a New Bedford police station.

He’d been arrested for drugs and desperate to avoid jail time. The police who nabbed him knew all about him, his affiliation with a local street gang, his past arrests, and the stakes at play.

Trust us, the detectives said. Help us. We can make your case go away.

When New Bedford police signed Daniel up as an informant, he says, they told him he'd only have to help them in one gun case. (J.D. Paulsen For the Boston Globe)

He’d had a choice, of course. But he said it didn’t feel, at least in that moment, like much of one. And so he took the deal, signed a paper, and joined the ranks of confidential law enforcement informants, becoming the latest local foot soldier in the nation’s endless drug war.

He didn’t know then that his work would never be done. That even though he played by the rules, provided information he said led to arrests, did what was asked of him again and again, rules didn’t matter. Because when it comes to confidential informants, the New Bedford Police Department doesn’t follow the rules.

Over the last 30 years, New Bedford police have perverted the confidential informant system in countless ways, the Globe Spotlight Team has found. Officers have slept with informants, coached informants, lied about informants – and worst of all, endangered informants much like this one.

His arrangement with police, confirmed through department files, court records, and law enforcement sources, was one built on trust but undermined by betrayal from the department that pledged to protect him.

His backstory is known only to a handful of people, including a reporter who has received dozens of calls from prison over 18 months, the phone connection often tenuous but the desperation crystal clear.

“I just need your help …,” Daniel said one night through the sobs.

“Please.”

Daniel, who is serving time in a Massachusetts prison for his role in two shootings, called a Globe reporter from prison dozens of times over the last two years. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

This connection began with a tip from a police source, months into a Globe Spotlight investigation into informant-related police corruption in Massachusetts.

A former law enforcement officer, outraged at what he’d witnessed during his time in the department, pointed a reporter to a New Bedford police internal affairs investigation. The heavily redacted file laid out the broad strokes of this case. Additional details, from other sources, cross-referenced with other court records and files, led to a possible home address, where a letter outlining the Spotlight Team’s interest in police misconduct prompted a phone call.

The informant wanted to hear more and agreed to a 15-minute visit in a county jail in a far corner of Massachusetts.

He spoke softly into a metal telephone handset, through a pane of security glass, confirming information that only the informant cited in the police files could know.

He ultimately agreed to share his story on the condition that the Globe Spotlight Team not publicly identify him or release details that would put him in additional danger. This story will use the pseudonym Daniel.

Listen to the podcast

Daniel is just old enough to legally buy alcohol, but could pass for much younger. He has pimples on his cheeks.

His teen years were marked by arrests for drugs, assault, gun possession. One for domestic violence. He was a low-level member of a feared New Bedford street gang. As part of the group, he acknowledges, he took part in two shootings, though he maintains he never wounded anyone.

Through the streaked security glass, his eyes appear wide and seem to dart around endlessly, behind him, to his sides, over his visitor’s shoulder.

He said he is not seeking sympathy and takes responsibility for the things he’s done and the decisions he’s made.

But so, too, he believes, should the New Bedford Police Department.

Daniel found trouble early.

He said he was smoking weed by 13, selling it soon after. He got jumped by some rivals at 14, which prompted him to buy his first gun. It cost him a few hundred dollars. He said he carried it with him wherever he went, though never into his grandmother’s house, because some places, he believes, are sacred.

As the years passed, he found himself increasingly drawn to action and danger. In New Bedford, he found both, in a local gang with a savage reputation. The group trafficked drugs and guns, clashed violently with rivals. Through the years, its members have been linked to murders.

A man walked the streets near the bus station in downtown New Bedford. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

And though the terrain has shifted a bit in recent years with the arrival of more organized national gangs, his gang remains a top target for New Bedford police.

Though far from a kingpin, Daniel had some clout in the group. He was trusted with storing weapons and moving drugs, police would later say, and was known to interact with some of the organization’s top members.

To an enterprising detective charged with tracking down guns and drugs, he represented something else.

Opportunity.

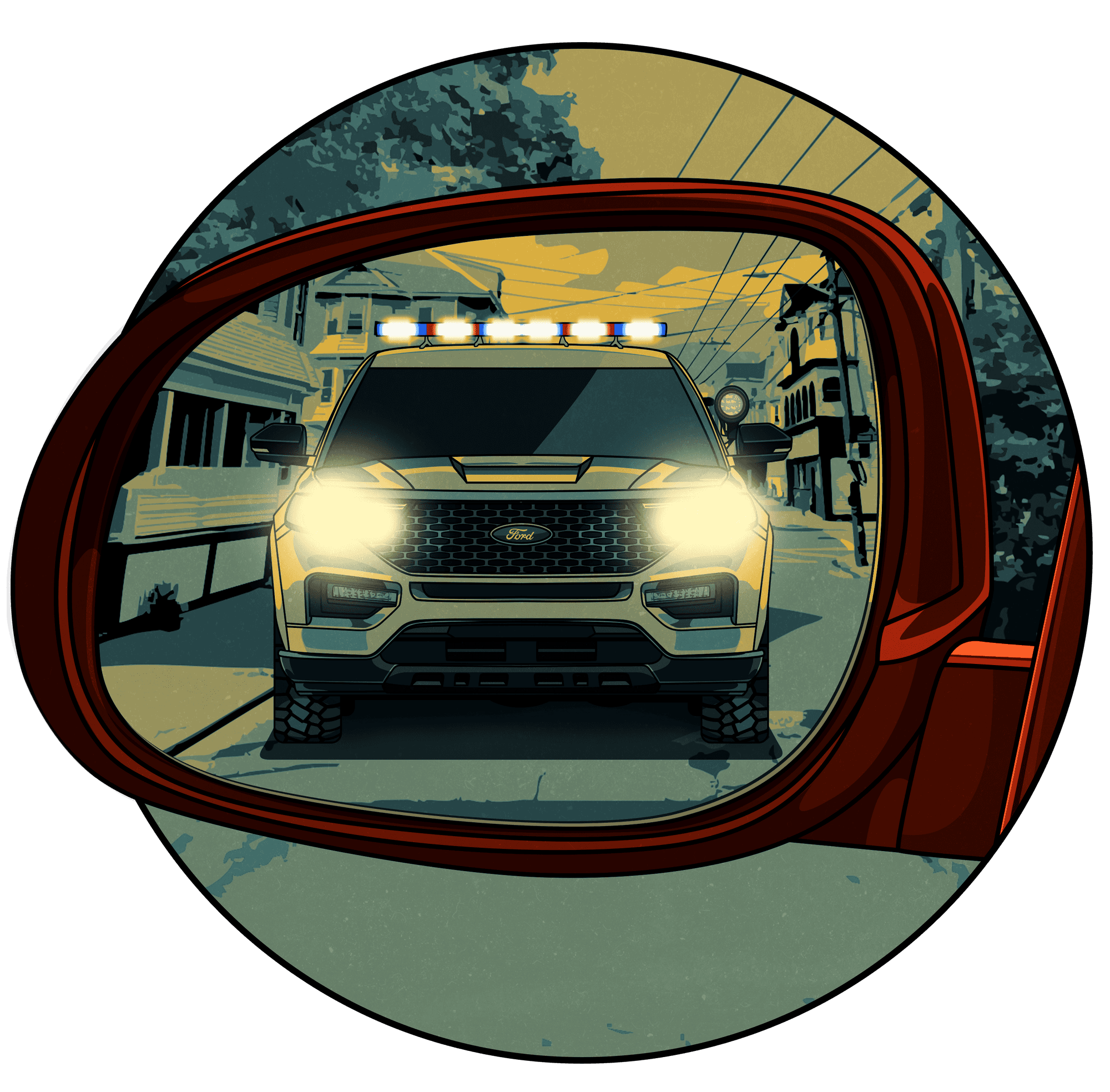

The Globe commissioned illustrations of key events for this series. In order to avoid identifying certain sources, we chose not to depict specific individuals. Illustrations are instead an artist’s rendering of events, people, and concepts.

The chance encounter took place one rainy night in 2021 in New Bedford, in a densely packed neighborhood of weathered triple-deckers, auto repair shops, and greasy takeout spots. Police lights suddenly flashed in the rearview mirror.

Pulling to the curb, Daniel quickly passed the drugs he was carrying to a friend.

The cops found nothing on him. But an officer discovered the drugs on Daniel’s friend.

Police brought Daniel back to the station on Rockdale Avenue. There were two officers: Nathaniel Almeida, a detective in the narcotics unit, and a supervisor Daniel knew only as “Pigeon.”

After they arrested him, New Bedford police offered Daniel a deal: Help us get a gun off the street, and this case will go away. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

The officers got right to it: They knew he ran with a notorious gang. They wanted to make a deal.

They told him no one would ever know. That it would be a brief alliance.

Help get us a gun, he said he was told. And you’ll be done.

Raised on gangland movies and hip-hop songs that scorned snitches, Daniel knew what he was supposed to do: Wave them off, demand a lawyer. Above all else: Keep his mouth shut.

The city’s streets were full of stories of suspected snitches being beaten, killed, or “walked off” — a kind of public, permanent shunning that some consider worse than physical harm. Not long before, a woman had been discovered at dawn, bloodied and beaten at the edge of a New Bedford park, the victim of a brutal kidnapping and assault handed down because someone thought she provided information to police.

Still, after a childhood spent in an endless circuit from courtrooms to holding cells to juvenile detention centers, the idea of going back inside felt like more than Daniel could bear.

In this moment, alone in a police station, all he wanted was to go home.

So when one of the detectives slid a sheet of paper in front of him — official confidential informant registration paperwork — he made a decision.

He’d do what they want. He’d get them a gun. And then he’d be done. No one would ever know.

Deal.

Daniel helped police in one gun case, seemingly fulfilling his deal. But they kept calling. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

For police, the benefits of a well-positioned snitch are clear. Who better to provide a peek into the illicit world, after all, than those living and operating within it? Informants also make the cases that bring accolades, promotions. By many accounts, New Bedford Police Chief Paul Oliveira built his career on the whispers of informants.

But for those on the other end of these shadow agreements, the benefits are far more ambiguous.

In most cities, including New Bedford, policies aim to provide certain protections. Informants are registered and vetted by police, their identities kept under lock and key, secret to all but a handful of police personnel. They’re promised cash payments, leniency in their own criminal cases, and — in some instances — the freedom to break the law with impunity because the crimes they help squelch are deemed more important.

In exchange, they’re sent — with no training and no protection — into the city’s darkest corners, to serve as the eyes and ears of police.

The Elm Street Parking Garage in fading daylight. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

“‘Confidential informant’ is really a misnomer, because they’re not providing just confidential information,” said Lance Block, a Florida-based attorney who has helped craft legislation aimed at establishing protections for informants. “I call them ‘civilian operatives’ ... because they’re doing what police officers do.”

He questions the whole premise.

“We don’t use civilians to direct traffic at a football game, and yet we’re going to use civilians to go undercover and potentially put their life at risk?” he adds. “It just makes no sense.”

To survive as an informant requires an extraordinary level of trust. Trust, above all, that police will protect their identity.

It is a bargain, Daniel would learn, that police don’t always keep.

“[Law enforcement does] the most ungodly things, and the only thing I can see is that there’s no oversight whatsoever,” said Michael Levine, a former longtime agent with the federal Drug Enforcement Administration who has been publicly critical of policing’s use of informants.

“Informant handling has become, in my opinion, a real danger to the public,” Levine said in a Globe interview. “Where are the rules? Where is the oversight?”

Some states have sought to implement safeguards. Minnesota recently passed a law designed to protect drug case informants. North Dakota banned the use of juvenile informants, while California enacted guidelines around using teenagers.

But in Massachusetts, where thousands of informants are currently at work, there is not a single law on the books dedicated to their safety, experts told the Globe. Police here are free to send anyone — addicts, the mentally ill, even children — into potentially deadly situations.

Advertisement

It took Daniel just a few days, he said, to deliver on the deal with Almeida, the New Bedford narcotics detective.

Daniel went to a party and set his sights on a target. Then he alerted Almeida. That day, a traffic stop led to the seizure of a gun.

There were nerves. Then guilt, Daniel said. Then relief — it was over.

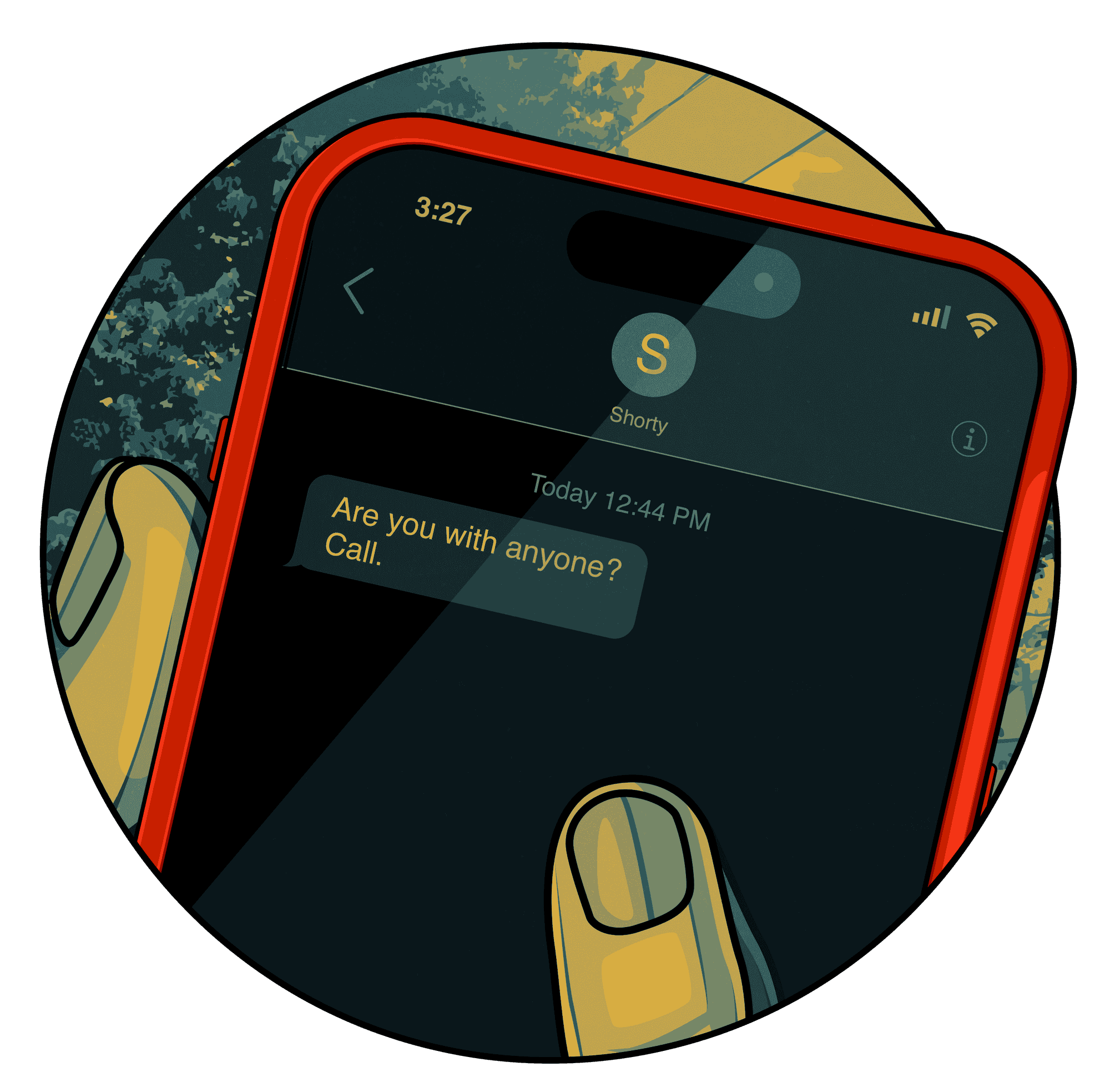

But the calls from Almeida continued, he said.

The second time, Daniel figured he might still owe him. One gun for his freedom wasn’t much.

But the third time, and the fourth time, he said, he realized the relationship wasn’t going to be the short-term arrangement Almeida promised.

Soon, the calls are coming constantly. Texts, too:

Are you with anyone?

Call.

“It became … ‘What’s going on? Who did this? Who did that?’” Daniel said in an interview. “And I’m telling him: ‘There’s a gun here, there’s a gun here, there’s a gun here.’”

Daniel told no one of this arrangement. Not friends or family. Not even his mother.

In his phone, he kept the officer’s name saved as “Shorty.”

Daniel's handler called him frequently, he said. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

For his part, Almeida, a young detective, was doing what drug cops before him did, what the police chief wanted: Making arrests, getting statistics.

Asked later why he�’d continued to help Almeida, Daniel said he didn’t believe he had a choice. At any point, he reasoned, Almeida could grow angry with him and reintroduce the initial drug charge or target him for new offenses.

Worse, there was the underlying fear that if he stopped being useful, there was nothing to stop Almeida or another officer from outing him as an informant.

The thought terrified him.

“Whatever they said, I would do it,” Daniel said.

“You just do it because that’s the police... I wasn’t going to win.”

He developed a snitching code: Never rat on family, never anyone from his inner circle. He became selective in his admissions. There were plenty of times, he said, that he was near five, six, seven guns — and didn’t say a word to his handler.

Still, the pressure to produce information was immense.

No matter how many tips he provided, how many guns he said he helped seize, it was never enough.

“If a shooting happened, he’s trying to reach out,” Daniel said of Almeida. “If they’re bored and nothing’s going on and they want to get something off the street, he’s calling. If he has questions about another kid, he’s calling.”

(Almeida would later describe the relationship in similar terms. “I would ask him about shootings in the area,” Almeida told investigators. “And he’s like, ‘Oh, yeah, I’ll find out for you.’ Sometimes he would come back to me and say, ‘Oh, yeah, like [this gang] shot up the South End.’”)

In the six to nine months he worked with Almeida, Daniel estimated he helped remove as many as 10 guns from the street.

One day, at the park, Daniel spotted a fellow gang member, a heavy-hitter with a long record: arrests for drugs and assault; battery on an officer; and for “stalking” a rival with a .38-caliber revolver. The Globe confirmed this man’s record and his involvement in this case through police records and sources and will refer to him, for safety reasons, by the name “Jack.”

Jack was a decade or so older, far higher on the group’s pecking order.

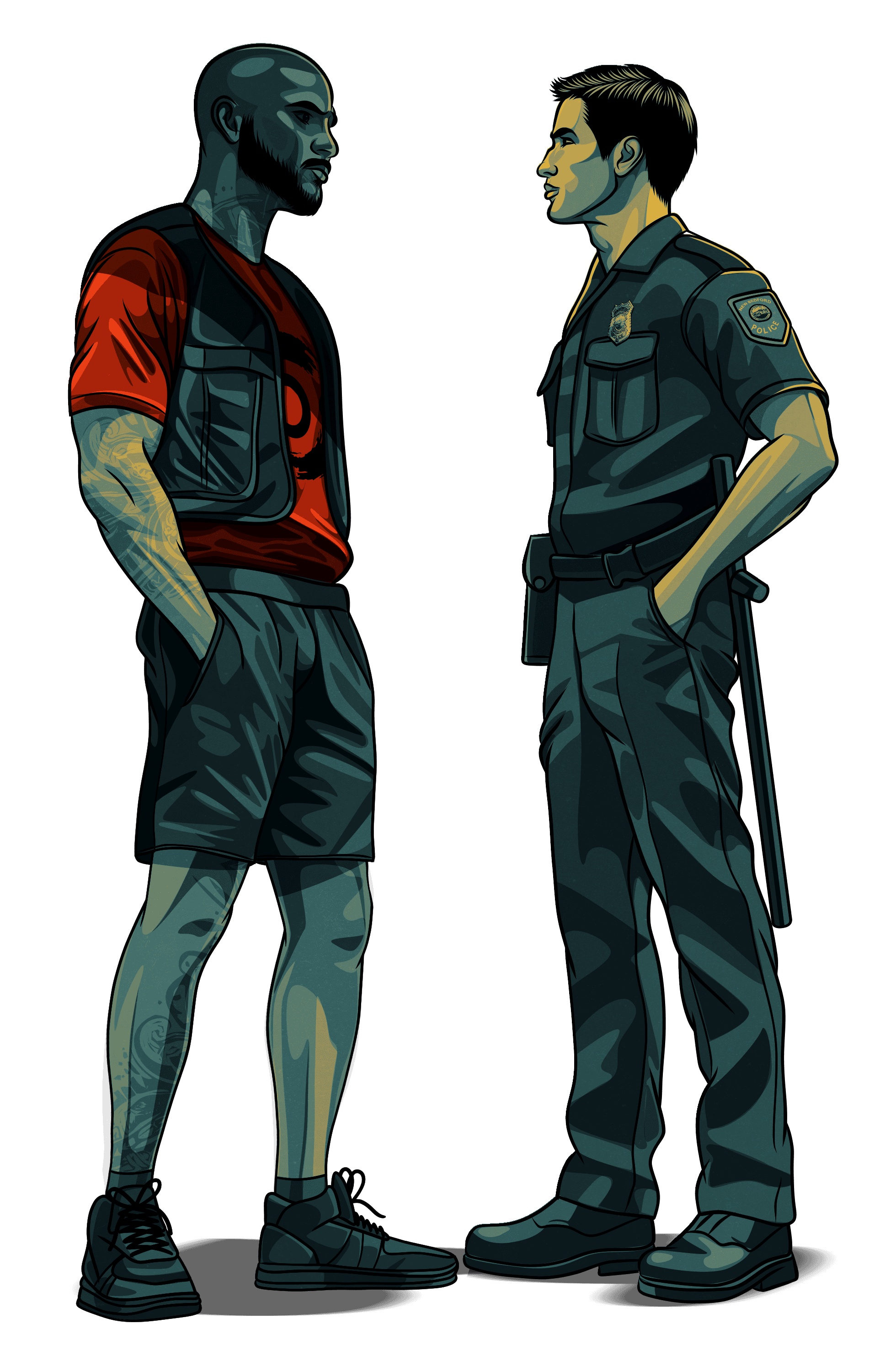

And in the park that morning, Daniel watched as Jack stood talking to a New Bedford police patrolman, a young officer with blue eyes.

A police officer met with a man at a park. (J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

It made for an odd pairing — two people on opposite sides of the law — though their encounter appeared cordial.

Afterward, Daniel approached Jack.

Who was the cop? he asked. Was he messing with you?

But it wasn’t like that, Jack explained. He and the blue-eyed officer went way back, he said. They’d grown up together, gone to high school together.

We’re mad cool, was what Daniel heard.

And Jack offered another telling tidbit, a piece of information that Daniel would file away.

The cop, Jack said, tells me everything.

(J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe)

A few months into Daniel’s work as an informant, blue lights appeared once again in the rearview mirror.

This time, it was a Massachusetts state trooper, who happened to recognize Daniel from an earlier interaction. The trooper asked: You still working for the New Bedford police?

This kind of exchange is common. In New Bedford and elsewhere, informants are generally given a pass in minor criminal matters. A good informant, after all, keeps company with criminals.

But as Daniel shared his information with the trooper, and seemed poised to go on his way, he suddenly spotted another officer nearby.

It was the blue-eyed cop from the park, Jack’s longtime friend, the one who supposedly tells Jack “everything.”

Daniel watched as that officer, listening to the exchange, scribbled something into his notebook.

The officers had barely pulled away when Daniel pulled out his phone and dialed Almeida.

He told Almeida about the blue-eyed officer who supposedly shared information with his fellow gang member. He was certain he was in grave danger, that the officer would out him to Jack.

Advertisement

Almeida would later tell investigators about this phone call. He recalled Daniel being in tears. And he said he immediately sought out his blue-eyed colleague, Alex Polson, and arranged a meeting.

The two colleagues met that same night at the department’s South End station. Polson acknowledged he was a childhood pal of Jack.

Almeida was blunt.

This kid will get killed if he gets found out, Almeida told Polson.

The message got across.

“He was like, ‘No, I completely get it,’” Almeida told investigators.

Not long after, Almeida called Daniel to tell him the matter had been handled. He’d spoken with Polson. Daniel’s secret was safe. Their work together could continue.

What Almeida didn’t do was report any of this to a supervisor or to anyone inside the department.

In the months following the Polson scare, Daniel continued to help police — and cause trouble.

He landed back in jail, following a confrontation with a group of rivals. And it was there, he said, that he first began to hear whispers about his suspected connection to police.

Daniel shrugged the comments off.

But not long after, he said, following his release from jail, he was directly confronted. By Jack.

They were at a local convenience store one night, he said, when Jack casually brought it up.

You know that cop I’m cool with? He said he put a stop on you, and he said you’re no good.

Daniel’s stomach dropped.

Immediately, he denied it.

“I said, ‘What? That’s crazy, he doesn’t know what the [expletive] he’s talking about,’” he recalled.

Jack didn’t push it. Maybe the cop got it wrong, he allowed. A case of mistaken identity.

They went on their way. But Daniel was shaken.

Briefly, he considered disappearing. But he had no money, and besides, where would he go? Everything he knew was in New Bedford.

His recent jail stint, he reasoned, provided a bit of cover; if he was working with the police, why hadn’t they helped him beat the charge?

The Ash Street Jail in New Bedford. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

Associates began to watch him closely, he said, or avoid him all together. He understood this; it’s the same way he’d once treated suspected snitches.

Every conversation, every interaction, felt like a test.

So it was no coincidence, he believed, when — a few weeks after being confronted by Jack — a group of older gang members approached him one night.

They gave him a handgun and an order. Don’t come back, he said he was told, until you empty the gun.

In that moment, Daniel had no time to gin up an excuse. No time to say he was running late to meet his girl, that he had somewhere else to be. To decline, he understood, was to admit that what the cop was saying was true.

He took the gun, climbed into a stolen car. He and several other gang members set out for a rival neighborhood.

As they drove, his mind raced, he later recalled. He prayed they’d be pulled over by police on the way, or that they wouldn’t find anyone to target.

And for a brief moment, it seemed his wish had been granted. No one was there.

Let’s try one last place, one of his associates suggested.

Nearby, a car idled under a street lamp. A group of young men had made a pitstop to retrieve a forgotten ID. They didn’t notice the car creeping to a stop nearby.

Daniel didn’t recognize them. He wasn’t even sure they were gang-affiliated.

Yo, that’s them, one of his associates said. Hop out and blow.

Advertisement

Police recovered numerous spent shell casings from the scene, from at least three guns. Bullets had pierced an apartment door frame, a dumpster, and a parked car.

Miraculously, no one was hit. But the brazenness of the attack prompted a heavy police response.

Within hours, a department-wide email went out. In it, investigators identified three primary suspects. It’s unclear whether Daniel’s name was included. One was a younger gang member who happened to be Jack’s cousin.

Police records, internal affairs files, and interviews detail what happened next.

In the wake of the email, Polson, Jack’s blue-eyed police friend, called the detective working the shooting. The detective barely knew Polson, who told him the Police Department had it all wrong. Polson said that Jack’s cousin, the one identified in the email, wasn’t “a gun kid.”

This was false.

“Lance Block, a Florida-based attorney“We don’t use civilians to direct traffic at a football game, and yet we’re going to use civilians to go undercover and potentially put their life at risk?”

Two years earlier, New Bedford police had booked the cousin with illegal gun possession.

Polson’s pitch to the detective to look elsewhere didn’t end there.

Polson made an offer: He knew this young man’s cousin, Jack, from way back. He could reach out to the cousin, try to find out more.

The detective later recalled his unease with the offer.

Just be careful, the detective warned Polson.

Later that night, Polson met the cousin in the parking lot of a waterfront bar. Immediately, before Polson could even speak, the cousin denied any involvement in the shooting.

It was clear, internal investigators would later note, that the cousin had been tipped off that he was a suspect.

Polson never documented this parking lot meeting — a fact that would later draw scrutiny from internal investigators.

Not long after, police surrounded a home where Daniel was staying, the location of which only a few fellow gang associates knew.

Again, Daniel was handcuffed and brought to the city’s police station.

Again, he sat before two detectives.

And again, he said, they made an offer.

The police station on Rockdale Avenue in New Bedford. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

Before the interrogation room camera began filming, Daniel said, the detectives told him they knew all about his work as an informant with Almeida. They wanted to set up a similar arrangement.

Tell us what you know, they said, and we’ll take care of you.

Daniel laid out his story for the investigators.

He told them about Polson, and his connection to Jack. About the State Police stop and the eavesdropping by Polson. About when Jack accused Daniel of being a snitch, and about the suspicions he’d faced since.

Daniel made no effort to conceal his wrongdoing.

He told them about the retaliatory shooting. He’d been following orders, he said, not to return until his clip was empty.

He also told police about his role in a second shooting, just days later. Like the first shooting, he said, he’d been pressured into taking part and fired into an empty vehicle.

To the detectives, he likened his situation to the movie “In Too Deep,” in which Omar Epps plays an undercover cop who infiltrates a violent street gang. Epps’s character must participate in a shooting or risk outing himself; he participates but intentionally avoids striking anyone.

Daniel said he didn’t have much of an option. “I shot around him.”

As he would later explain, he believed these admissions to police were confidential, much like the conversations he’d previously had with Almeida.

Soon, however, Daniel was charged in both shootings.

While his information brought a quick arrest, the kind that police tout in press conferences and news releases, it posed a problem for the department.

Daniel’s admissions and allegations were recorded on camera, as part of a major criminal investigation. They were impossible to ignore. And so, internal investigators requested Polson, the blue-eyed officer, come in for questioning.

Unlike the informant, Polson didn’t face investigators alone. He arrived with a union representative and a lawyer, both of whom sat in on the interview.

Daniel told police that he believed Officer Alex Polson had leaked his identity, putting his safety at risk - and setting off an internal probe into Polson. (J.D. Paulsen For the Boston Globe)

In it, Polson acknowledged he knew Jack, the high-level gang member.

Polson denied leaking Daniel’s identity as a police informant or passing along any sensitive police information to gang members.

As for his off-the-books meeting with Jack’s cousin in the bar parking lot? Proactive police work, he explained.

Still, there was plenty that Polson could not explain to internal investigators.

He offered no rationale for his failure to document the parking lot meeting, or his false claim that the cousin had no history with guns.

When investigators asked Polson for his text messages with Jack, Polson said that it was impossible. He’d deleted them all. He said he regularly cleaned out his phone.

Get Snitch City in your inbox

Sign up to receive Spotlight reports and special projects, like Snitch City

In addition, after learning of the department’s investigation, he’d deleted Jack’s contact information from his phone entirely.

Investigators were puzzled. Why?

“I’m not gonna risk my career over this,” Polson replied.

Yet, three text messages did survive.

And those messages cast doubt on Polson’s claims.

In one, Polson clearly warns Jack that New Bedford police are intensifying their investigation into a recent gang shooting.

“They’re def going to bump the heat up,” Polson wrote to Jack.

In another, Polson alerted his childhood friend that a pair of younger gang associates were “very known” to detectives.

Throughout Polson’s interview, internal investigators expressed skepticism in his claims.

At one point, a lieutenant quizzed Polson about an incident from many years earlier. The lieutenant had heard Jack once beat up a classmate that was bullying Polson.

Polson struggled to respond.

“Nah. So he, uh, he did fight this kid … once. The kid did bully me…” he said.

“But is that when you felt loyalty to him?” the lieutenant asked. “When he stuck up for you in a fight?”

“I wouldn’t say … I wouldn’t say, ‘loyalty,’” Polson said.

The interview ended soon after.

Deep in the transcript of this interview, amid redacted blocks of text, are several statements by Polson that add another layer to this complicated saga.

When investigators were looking into Daniel’s role in a shooting, Jack offered Daniel’s nickname.

”[Jack] was able to identify the kid for me,” Polson told internal investigators. “Then he just asked, uh, to not be on record.”

Investigators seemed skeptical and pressed Polson. “This guy being a gang guy, why would he trust you to give you that nickname when you called him up on the shootings if you’re not that close? He wouldn’t give it to any other cop. I’m sure if a cop called him, he’s gonna say, ‘Go pound tar.’”

“He gives you a nickname of that guy. Why would he do that if you’re not as close as you say you are?”

It was the second time, Polson said, that Jack had mentioned Daniel’s name to Polson. This means that Polson and Jack had specifically discussed Daniel, and that Jack, himself, was providing information on one of his own.

In an interview with the Globe, Polson denied sharing Daniel’s name, or any other sensitive police information with gang members.

“I know I didn’t do anything wrong,” he said. “I wasn’t sharing information.”

Polson said the allegations were false, part of an effort by Daniel to get himself out of trouble. Polson said he only learned of Daniel’s informant status when the internal investigation commenced. But that contradicts what he told internal investigators in 2022 — that he first learned of Daniel’s status when Almeida sought him out.

Asked about the discrepancy, Polson backtracked, saying his 2022 statement was correct. Polson also acknowledged that he and Jack grew up together and were friends. But they don’t hang out today, Polson added.

Then, without prompting, Polson went on to release to the Globe the name of the person who implicated Daniel in the shooting.

Polson said it’s widely known in New Bedford’s criminal world who is working with police.

“It’s kind of messed up over there, because everybody knows who’s telling,” he said. “It’s like, common sense.”

Polson ended the call to focus on his patrol shift and pledged to continue the conversation. He did not respond to repeated follow-up messages.

The New Bedford Police Department’s Professional Standards Division closed its two-month-long investigation into Polson on Oct. 19, 2022.

Given the seriousness of the allegations — that an officer in their ranks endangered the life of an informant by revealing his identity to a known gang member — the scope of the internal probe was remarkably limited.

The police in New Bedford have a long history of abusing the confidential informant system in the fight against drugs, guns, and gangs. (Lane Turner/Globe Staff)

Investigators made no attempt to retrieve Polson’s phone records, which could’ve shown the extent of his communication with Jack. Nor did they interview Jack or his cousin. In total, four people were interviewed. Three of them were New Bedford police officers. The other? Daniel.

The report does not conclude that Polson outed Daniel.

Still, it was critical.

The investigators expressed concern that an officer could be “close enough to a gang member [that] he can call for a meet with these two unsavory characters, and get the meeting,” They also found it “suspicious” that Polson had deleted Jack from his phone upon learning of the probe.

Ultimately, the investigators recommended a disciplinary charge of “releasing information that may aid others.”

It’s a serious breach of department policy, one that could — or should, experts say — land an officer on the state’s Brady List of problem officers, which would potentially jeopardize his ability to testify in a criminal case again.

But this is New Bedford.

Advertisement

The report landed on the desk of chief Paul Oliveira — the same Paul Oliveira that the Spotlight Team found had misused the informant system as a drug cop decades ago and landed in the FBI’s crosshairs. The same Paul Oliveira who, around the time of the Polson investigation, again came under FBI scrutiny, this time about the department’s trustworthiness.

Where New Bedford’s internal investigators saw subterfuge, Oliveira saw not much at all.

On the disciplinary report, the chief crossed out the recommended charge with his pen, deleting the serious charge Polson faced and replacing it with a much more benign rule violation.

Tom Nolan, a retired Boston police lieutenant who worked in the Anti-Corruption Division of internal affairs, told the Globe that the investigators’ findings were troubling.

“If you’re tipping off your buddies that they’re being looked at for criminal activity, you’re going to get fired for that — or you should get fired for that,” said Nolan. “You should be gone for that.”

Nolan also was surprised that Oliveira overruled his internal investigators.

“It is extremely unusual for a chief to basically alter the outcome of an internal affairs investigation to say, ‘No, this will not be sustained,” Nolan added.

In spring 2023, with this case behind him, Polson resigned from the New Bedford Police Department. He soon joined the police force in nearby Wareham, which issued a press release calling him a “valuable addition to our department and our community.”

The voice on the other end of the prison phone line was soft, resigned.

“It ruined my life,” Daniel said of his time as an informant. “It took my whole life away.”

“I wish I [had] a [expletive] time machine.”

He’s been in prison since pleading guilty to his role in the pair of shootings.

Initially, for his protection, he was sent to a facility far from New Bedford. But once he was convicted, officials transferred him to a prison closer to home. It’s peppered with gang members from New Bedford.

He recounted the time an inmate threatened to stab him for being a snitch.

In New Bedford’s Police Department, few things have changed. A year-and-a-half ago, the city’s Police Department announced its newest member.

It was a homecoming of sorts – the return of a familiar, blue-eyed officer.

Alex Polson.

He’s a patrolman now, working out of the same South End police station.

Andrew Ryan of the Globe staff and Spotlight editor Brendan McCarthy contributed to this report.

Feedback and tips can be sent to the Boston Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected], or by calling 617-929-7483. Mail can be sent to Spotlight Team, the Boston Globe, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

Credits

- Reporters: Dugan Arnett, Andrew Ryan

- Editors: Brendan McCarthy, Gordon Russell, Mark Morrow, Kristin Nelson

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Kirkland An

- Illustrations: J.D. Paulsen for the Boston Globe

- Photographer: Lane Turner

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Ronke Idowu Reeves, Adria Watson, Diamond Naga Siu, Amanda Kaufman

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Legal review: Jon Albano

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC