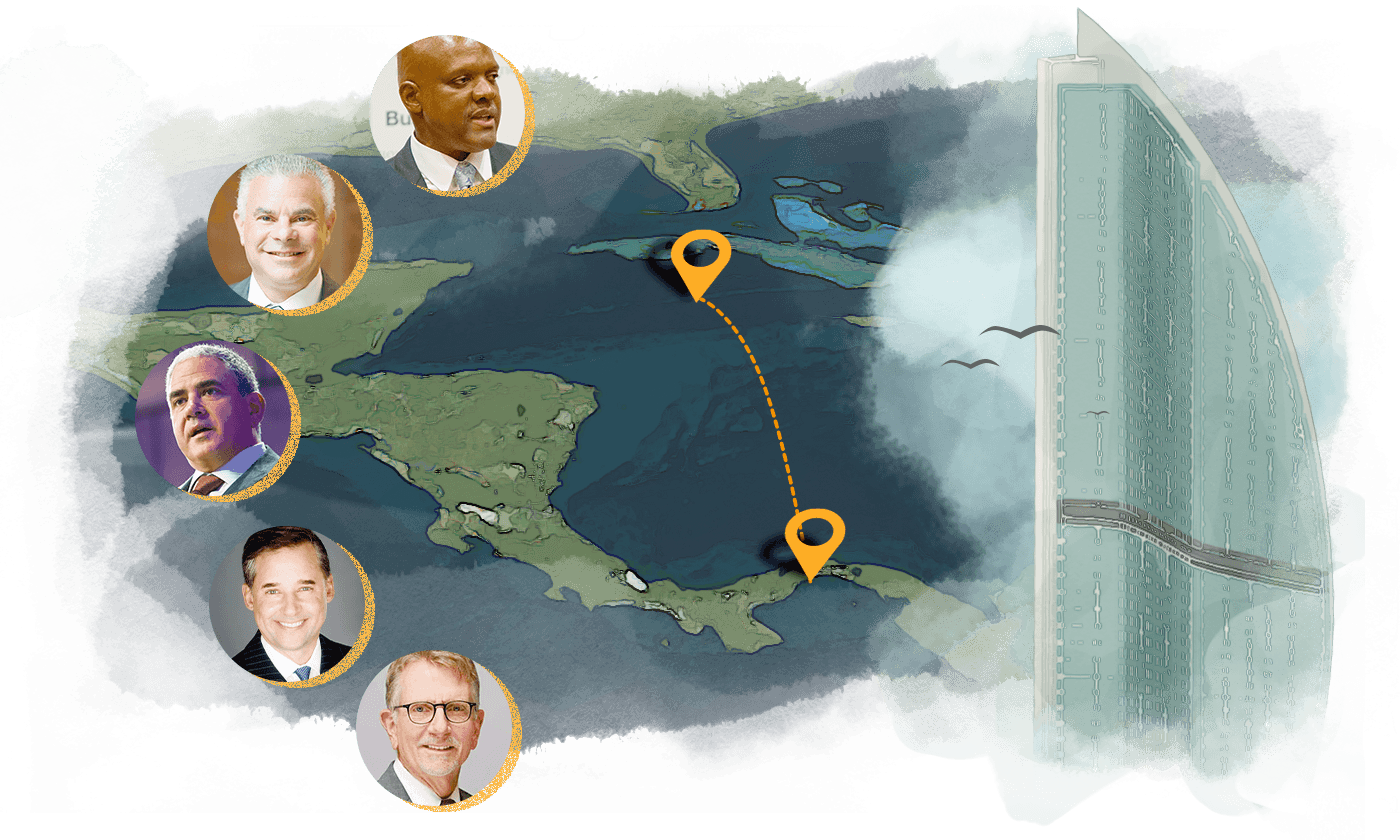

From top: Rubén José King-Shaw Jr., Dr. Michael Callum, Dr. Ralph de la Torre, Herbert Holtz, and John Doyle. (photo illustration by Ashley Borg/Globe Staff; Michael Nagle/Bloomberg, Confluent Health, FIU, Steward Medical Group, mapcreator.io)

Steward Health Care raided the coffers of its in-house malpractice insurer, leaving claimants, doctors in limbo

When Melissa Williams looks down at her ruined right hand, all she sees is loss.

Two fingers and part of her palm have been amputated.

Gone, too, is her financial security. Williams has been unable to work regularly since 2017, when she entered a Steward Health Care hospital in Melbourne, Fla., for a common operation, and a botched IV insertion led to searing pain and a host of complications that continue today. Williams sued Steward in 2019 for what seemed an egregious case of malpractice.

Five years later, and facing $500,000 in medical bills, she hasn’t seen a dollar from the hospital chain.

Explore the full project

- Death, indignity, despair: The human cost of Steward’s neglect

- How Steward’s CEO used corporate funds as the company crumbled

- Meet the corporate board that OK’d many of de la Torre's decisions

- Read the stories of patients who died after seeking care at Steward hospitals

- How a real estate firm grew with Steward, keeping its shaky finances secret

It is unclear why no settlement has been reached, and Steward continues to fight the case in court. But a Globe Spotlight Team review points to a possible explanation for the frustrations Williams and scores of other Steward patients have experienced. Executives at the overextended hospital chain have treated their in-house malpractice insurer, TRACO, like a piggy bank, pulling cash from it at will, and severely depleting the assets meant to cover claims of medical harm.

Indeed, Steward was so eager to spend TRACO’s money that it moved the insurer from the Cayman Islands — a traditionally permissive locale for foreign investors — to Panama, where certain key regulations were even more lax. Auditors had been pushing Steward to shore up TRACO’s balance sheet. But executives had other plans for the insurer’s assets and believed Panama would allow them more freedom to spend, according to three Steward insiders and internal company emails.

The aggressive draining of TRACO’s balance sheet has Melissa Williams wondering if she will ever be compensated for her losses. She and her 14-year-old son recently had to put their belongings in storage and move in with a friend.

“What if your lawsuit never settles?” asked Williams. “What if you never get a dime?”

Melissa Williams at Eau Gallery in Melbourne, Fla., where she is a member. (Jacob M. Langston for The Boston Globe)

At the time of TRACO’s relocation to Panama, executives at Steward — then growing from its base of nine Massachusetts hospitals into the largest private for-profit health care chain in the US — had already taken millions of dollars from its insurer, whose leadership overlaps substantially with Steward’s. The borrowing accelerated as Steward hemorrhaged money, with enormous IOUs from the hospital chain replacing TRACO’s funds. By the end of 2023, TRACO’s books showed $99 million in outstanding loans and interest, almost all of it owed by Steward. Separately, TRACO listed $176 million in “accounts receivable.” Bankruptcy documents make clear that most of that sum is owed by Steward.

The real value of those IOUs today is uncertain at best, given Steward’s declaration of bankruptcy in May. As of August, TRACO listed just $3.5 million in cash — an absurdly small sum when stacked against the 517 malpractice claims against Steward that are either pending, like Williams’s case, or settled but unpaid. Steward’s lawyers have said the remaining claims could cost as much as $200 million to settle.

The grim financial picture means that patients who suffered from shoddy care at Steward facilities could be harmed a second time, when they are unable to collect what they’re owed.

What happens when medical malpractice insurance runs dry

These Steward patients suffered from alleged misconduct or medical errors — some fatal — and have not seen settlement money. Read their stories.

Henrietta Randolph-Aronoff

Keith Wade

Bob Newhall

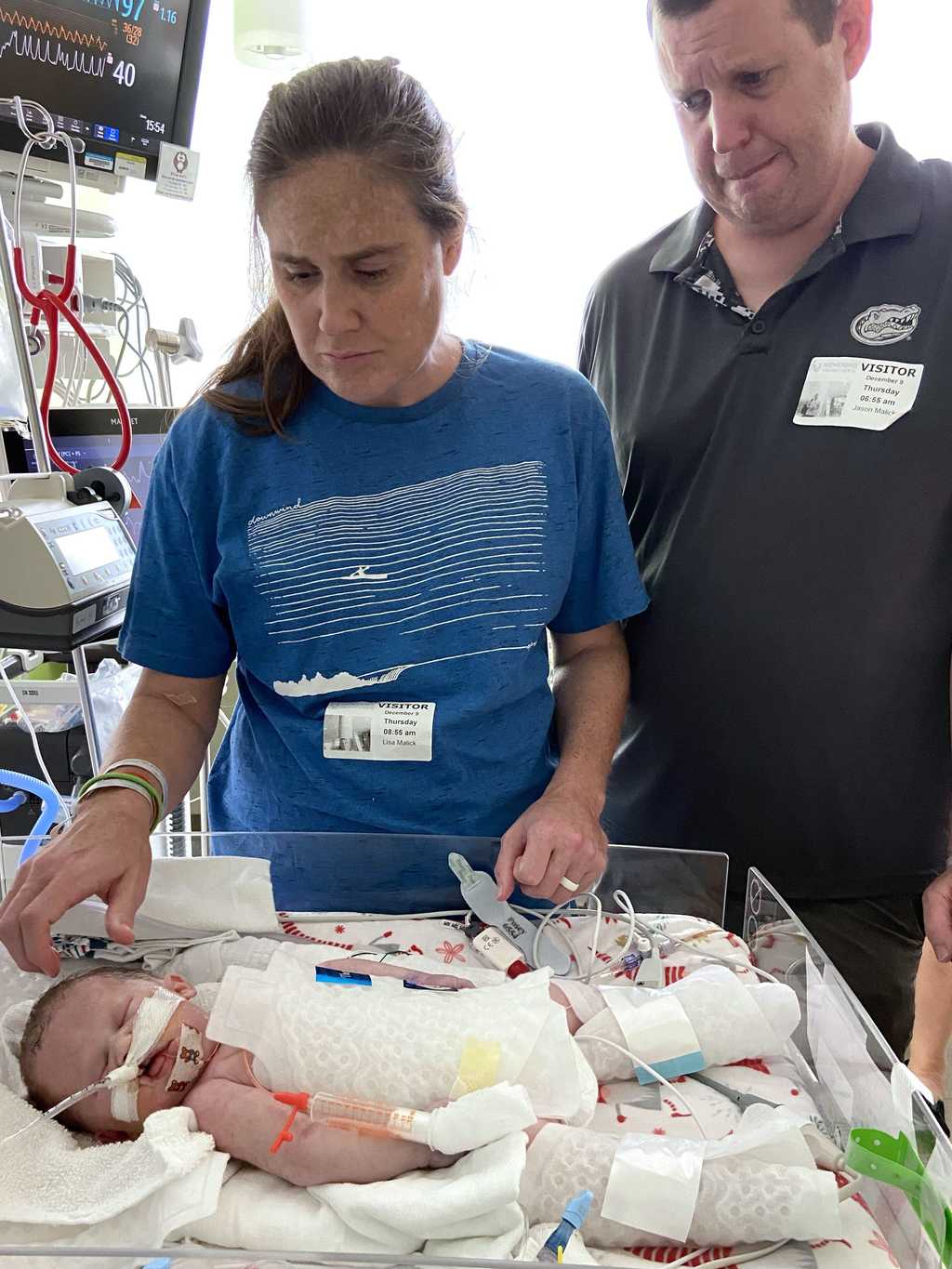

J.D.C.

Lillian Malick

Kyela Pixler

At risk, too, are some of the thousands of doctors who worked for the chain and now wonder if the malpractice insurance that was supposed to be protecting them is worthless. At least one lawyer involved in suits against Steward has begun suing doctors personally, betting they have deeper pockets than the chain.

The strip-mining of TRACO and its impacts have gotten limited attention amid a larger pattern of questionable financial dealings at Steward, whose owners took hundreds of millions of dollars in payouts even as their hospitals crumbled. The firm’s stunning collapse is now being investigated by a federal grand jury meeting in Boston.

Timothy Walsh, an attorney for TRACO, told the Globe that “TRACO is not insolvent as long as the debtors adhere to their obligations, which we expect them to do.” TRACO’s biggest debtor, of course, is Steward, which is broke.

TRACO officials declined to answer other questions. Steward representatives also declined to comment for this story.

Advertisement

Born in the islands

TRACO is what is called a captive insurer, a wholly owned self-insurance vehicle of the sort that many hospital systems prefer. Health systems like Steward typically pay premiums on behalf of their doctors, though some 200 Steward-affiliated doctors actually paid Steward malpractice premiums out of of pocket. The premiums are supposed to go into a pool that is used to litigate claims and pay them when necessary.

Money in the pool can be invested, ordinarily with a preference for low-risk vehicles that are easy to cash out. If the company manages its risk well and the pool grows large, some assets can be returned to the firm.

Decades ago, there was no mechanism to set up such captive insurers in the United States. So, in 1988, Steward’s predecessor — Caritas Christi, which was run by the Archdiocese of Boston — incorporated TRACO in the Caymans. The name is an acronym for Tailored Risk Assurance Co.

The Caymans’ reputation for permissiveness helped it become a business hub, but also landed the country on international watch lists for, among other things, failing to adequately combat money laundering. Over the last 15 years, the nation’s leaders tightened things up, and today, “the regulatory structure and requirements” of the Caymans match those of European countries, said Mark E. Reynolds, president of CRICO, the group captive insurer for many Boston teaching hospitals, which was long based in the Caymans.

Panama, by comparison, has not been a beacon of respectability. As Steward finalized its bid to move TRACO there in June 2019, one international body flagged Panama as vulnerable to money laundering. Another found it susceptible to tax evasion.

Captive insurers are rarely found in Panama

The Cayman Islands, with historically lax oversight laws, has long been a hotspot for captive insurers, ranking second in the world for the number of such entities in a jurisdiction. Panama, by contrast, is ranked 52nd. TRACO is one of just six captives located there.

| Rank | Country | Captives | Pct. of all captives |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Cayman Islands | 658 | 10.6% |

| 52 | Panama | 6 | 0.1% |

On top of that, Panama had little or no expertise in setting up and regulating companies like TRACO. The firm is one of only six captive insurers headquartered there.

Nancy Gray, who oversees captives in the region for Aon, a leading insurance consultancy, said she doesn’t know why an insurer would move to Panama. Not one of her firm’s 1,000-plus captive clients is located there.

The Cayman Islands “have been doing this for many years,” Gray said. “There is no reason to recommend a domicile without a developed practice … [and] regulators who understand the business and have been involved for a while.”

Advertisement

The wonders of Panama

But Steward’s leaders were eager to escape restrictions on how they could spend TRACO’s money. They saw Panama as a sanctuary, according to Globe interviews as well as internal emails obtained by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and shared with the Globe.

For instance, when auditors from Ernst & Young questioned whether Steward had given Panamanian officials ample notice of a change in finances, a Steward executive assured his colleagues that, unlike in the Caymans, it wouldn’t matter much.

“Seems like EY [Ernst & Young] is missing the ‘so what’ component here,” wrote Jacob Frumkin, Steward’s vice president for finance. “Whether or not we did something we shouldn’t have, the beauty of Panama is the ‘so what’ is not going to be that we’re not an insurance company anymore … it’s probably a discretionary fine of a $1,000 or something like that.”

Perhaps the most important distinction between Panama and the Caymans was the flexibility Panama allowed TRACO in using its money. In Panama, “there is no limitation on TRACO’s ability to loan or invest its assets,” Frumkin explained in an email to auditors and a group of fellow executives. TRACO had to keep a balance of just $150,000 in a Panamanian bank.

In another 2019 email, Steward’s chief financial officer John Doyle pushed for Steward’s lawyers to produce a letter explaining TRACO’s upcoming relocation. “This is needed to get EY [Ernst & Young] off of our backs re the need to fund the Cayman captive,” he said.

By May of that year, TRACO just needed a physical office to complete the relocation. TRACO’s president, Rubén José King-Shaw Jr., had an idea: How about his penthouse, in a swanky part of Panama City?

Rubén José King-Shaw Jr. (FIU)

The firm’s local attorneys balked, saying TRACO would need a “formal office, where the authorities can go and make inspections.”

King-Shaw pushed back. Less than a month later, he emailed fellow Steward executives with good news: Panama would allow TRACO to be domiciled in his penthouse.

Dr. Ralph de la Torre, Steward’s CEO, was jubilant. The move was finally on.

“Yay!” he replied in an email. “Great job!!”

‘Where the cash is’

Even as they plotted to move TRACO to Panama, Steward executives began stepping up the drawdown of TRACO’s treasury.

In 2019, they invested $132 million of TRACO’s money into Davis Hospital and Medical Center in Utah, which Steward had bought two years earlier.

Captive insurers typically invest in vehicles that are easy to cash out.

“If you needed to pay losses, to get funds for the captive, how are you going to be able to do that if you have to sell real estate?” asked Tim Slowick, who helps manage UMass Memorial Health’s captive. “Hospitals aren’t the easiest piece of real estate to sell.”

Steward did eventually sell Davis, in 2023. But there’s no evidence any of the proceeds went to TRACO. Instead, the amount TRACO listed in “investments” on its financial statements dropped by $132 million at the close of that year. And the amount TRACO said it was owed in accounts receivable jumped from $289,000 to $176 million.

Steward’s bankruptcy filings say that TRACO still owns a 30 percent share in Davis, but the hospital’s new owners, CommonSpirit Health, told the Globe they own it free and clear.

Steward, TRACO boards had significant overlap

TRACO, Steward’s in-house malpractice insurer, was overseen by many of the same people who ran Steward, including Dr. Ralph de la Torre. That may explain why Steward repeatedly raided TRACO’S accounts. Here's what it looked like in mid-2020.

| Name | TRACO position | Steward position |

|---|---|---|

| Dr. Ralph de la Torre | administrator | chairman and chief executive officer |

| Dr. Michael Callum | administrator | president, Steward Medical Group |

| John Doyle | treasurer | chief financial officer |

| Rubén José King-Shaw Jr. | president, administrator, representative | chief strategy officer |

| Herb Holtz | secretary, administrator | executive vice president and general counsel |

The IOUs continued to pile up after the move to Panama, according to emails reviewed by the Globe.

In December 2020, the insurer sent $5 million to another Steward business. Another loan was drafted in 2021, this time taking $6.7 million from a TRACO affiliate. The money was to be used to help acquire and develop a hospital in Colombia, the emails show.

“TRACO is where the cash is I am told and that is where Ralph wanted it funded from if possible,” wrote Mark Rich, then a Steward consultant and now the company’s president.

“TRACO is where the cash is I am told and that is where Ralph wanted it funded from if possible.”—Mark Rich, now president of Steward Health Care

By that time, Steward had stopped sending the premiums it was paying on behalf of doctors to TRACO, giving the captive an IOU instead, according to one former Steward executive.

TRACO’s habit of accepting IOUs and making loans to Steward, especially given Steward’s precarity, struck others in the industry as suspect.

“If you wanted to be sneaky, you could borrow money from your captive, move it to your parent company, and the captive would be holding an asset that would be that loan,” said Dr. Eric Dickson, CEO of UMass Memorial Health, which has a captive in the Caymans. “The value of that loan if your company went bankrupt is zero. We would never do that.”

While Panama’s rules were looser than those in the Caymans, TRACO nonetheless managed to break them eventually.

Last November, a month after Panama was removed from the international “gray list” for improving its anti-money laundering and financial regulation measures, the country fined Steward $25,000. TRACO was cited for “various irregularities with the administration, mitigation and control of risks,” according to a government website. The company was also cited for “refusing to submit accounting records of its operations.”

Reached by phone, Mary Arjona, chief of the Department of Administrative Law for the insurance department in Panama, said the details are confidential. Pressed further about the country’s rules for captives, she said: “Public officials do not answer these types of questions from journalists.”

The Panamanian government declined to answer written questions posed by the Globe.

Doctors, nurses at risk

Steward has filed for bankruptcy as its finances have cratered. TRACO has denied in bankruptcy filings that it is insolvent, and Steward has sought to assure its doctors and patients that TRACO continues to cover them, paying millions of dollars in defense costs, if need be. But most of TRACO’s assets are IOUs from Steward.

The companies are intertwined in many other ways. TRACO’s board still includes former Steward CEO de la Torre and another top executive, Dr. Michael Callum, though the two recently stepped down from leadership at Steward.

Steward has suggested it will resolve current claims through the bankruptcy — though that may simply mean offering victims pennies on the dollar.

Many former Steward doctors are dubious of the chain’s promises, partly because Steward has a history of not paying its defense counsel. Marc Edward Stewart, a lawyer from Arkansas, said in one of his cases, multiple Steward attorneys have quit over nonpayment.

A physician at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton has been worried about being sued after one of her patients was harmed last year. Months before Steward filed for bankruptcy, she called three law firms for advice. None wanted to represent her, fearing Steward would stiff them.

The physician asked not to be named over concerns of a potential lawsuit.

Advertisement

As TRACO executives, King-Shaw and Callum emailed doctors two months ago to assure them that their insurance was intact. Callum stepped down from TRACO shortly afterward.

The message left some providers incredulous, including Stephen Wood, who worked as a nurse practitioner at Carney Hospital until Steward closed it in August. He and a colleague purchased their own malpractice insurance in May.

“If I were to devise a prank call, this would be a great one,” Wood said. “‘All your medical malpractice is run … in Panama — by the same people who ran your hospital in the ground. But you don’t have anything to worry about! We will take care of it!’ It’s a joke.”

Some lawyers, doubtful they’ll ever collect from Steward or TRACO, have begun to target Steward doctors personally.

Ashton Hyde, a malpractice attorney, filed a suit against a Utah doctor and Steward over a problematic spine surgery in mid-2022. He recently refiled the lawsuit, this time only targeting the physician.

“We are going after the doctor individually and he is effectively uninsured,” Hyde said. “So his personal assets are exposed.”

The question of TRACO’s solvency could be relevant well into the future, because malpractice victims may bring claims years after an incident.

Two health systems — Lifespan and Boston Medical Center — that each acquired two Massachusetts hospitals from Steward have taken the unorthodox step of committing to protect their new employees from past missteps, should TRACO fail to cover them.

Melissa Williams and her son, Steen Fancher, 14, try to diagnose the problem with the 3D printer at the home they are staying at in Melbourne. (Jacob M. Langston for The Boston Globe)

Melissa Williams makes ice cream at the Melbourne home where she and her 14-year-old son are staying. (Jacob M. Langston for The Boston Globe)

Solvency never measured

TRACO’s troubles have drawn little scrutiny from the state agencies that oversee doctors and insurers, though Massachusetts regulations allow either the state Board of Registration in Medicine or the Division of Insurance to require insurers to prove “that funding of the entity is adequate.”

Michele Campbell, a spokesperson at the Insurance Division, asserted that the agency lacks the authority to request the relevant documents from an insurer that, like TRACO, is not licensed in Massachusetts.

The Board of Registration, which licenses doctors, acknowledged in an email from spokesperson Ann Scales that it does not seek financial documents from malpractice insurers. The board pointed to the Division of Insurance as the agency that would theoretically do so.

The board also asserted in an email that TRACO has been paying all its claims – an assertion disputed by multiple attorneys whose clients have unpaid settlements.

‘A bunch of loopholes’

TRACO’s depleted assets and Steward’s bankruptcy have left people like Yasmany Sosa in legal and financial limbo. Sosa’s 35-year-old wife, Yanisey Rodriguez, died a preventable death at Steward North Shore Medical Center in Florida on Sept. 7, 2022, seven days after giving birth to their first child.

Though Steward agreed to a $4 million settlement with Sosa in March, he has yet to be paid.

The money was never going to bring his wife back, or ease his grief. But it was going to help in other ways. Without his wife’s income, Sosa has had to change jobs and work longer hours, he said.

The bankruptcy has made him wonder if he’ll ever get paid.

“They killed my wife, that’s for starters. Second of all, they destroyed my family,” Sosa said through a translator. “This has all become a bunch of loopholes, legal strategies. This really is very difficult for me … I’ve already lost everything.”

Stephen Wood stood outside of the closed Carney Hospital. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

Brendan McCarthy and Hanna Krueger contributed to this report.

Feedback and tips can also be sent to the Boston Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected], or by calling (617) 929-7483. Mail can be sent to Spotlight Team, the Boston Globe, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

Credits

- Reporters: Jessica Bartlett, Liz Kowalczyk, and Elizabeth Koh

- Contributors: Brendan McCarthy and Hanna Krueger

- Editors: Gordon Russell and Mark Morrow

- Visual editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photos: Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff, Jacob M. Langston for The Boston Globe

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Kevin Martin

- Design: Ashley Borg and John Hancock

- Development and graphics: John Hancock

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC