Concetta McCarthy visited the gravesite of her beloved cousin, Gilberto Melendez-Brancaccio, on July 17 in Mt. Wollaston Cemetery in Quincy. Gilberto died at age 31 at Carney Hospital. She was like a sister to Gilberto growing up in Quincy. (Barry Chin/Globe Staff)

They died in hallways. In line. Alone. Their deaths are the human cost of Steward’s financial neglect.

Gilberto Melendez-Brancaccio often became confused and seized by religious delusions when he didn’t take his antipsychotic medication, and that was how the police found him, in June 2021, in a Quincy hotel, telling people he was God.

The police summoned an ambulance. “No,” Gilberto said at first. “I am God.” But then, as if his words and actions were operating on different wavelengths, he collected his wallet and phone, and went with the officers.

“Good,” Gilberto told them, according to a police report. “I’ll go to the hospital.”

He was a husky 5-foot-8, with a shaved head and sculpted goatee. His eyes were stunningly dark and expressive, often caught in photos with a look of melancholy. Perhaps that was from the sad things he had witnessed in his turbulent 31 years, such as his mother being consumed by mental illness, before Gilberto himself began exhibiting signs of schizoaffective and bipolar disorders.

He climbed without hesitation into the ambulance.

Even amid a psychotic break, he trusted in the hospital as a place where he could count on compassion and expert care.

His trust was misplaced — betrayed, in fact.

Gilberto Melendez-Brancaccio.

The ambulance drove him to Carney Hospital in Dorchester, part of the national Steward Health Care chain. It was a desperately depleted hospital, so starved for resources by its corporate bosses that some employees had begun referring to it by a dark nickname: Carnage.

Carney was but one piece of the failing empire of neglected Steward hospitals, some now shuttering for good or being parceled off in a bankruptcy fire sale.

The breadth and tragic consequences of Steward’s mismanagement have not yet been told in full. There has been a vast human toll, tallied in lives lost, suffering endured, physical injuries, and moral indignities. This Spotlight Team investigation is the first major effort to document the full dimensions of the harm done.

Gilberto, of course, had no idea. When he became combative, the Carney staff tried to calm him with antipsychotic and anti-anxiety medications. They put his arms and legs in restraints. Three times, he tried to flee; each time, he was again sedated and restrained.

By late morning, his heart rate had soared. His oxygen levels plummeted so low that nurses gave him a breathing mask.

Advertisement

Doctors ordered that Gilberto be continuously monitored; a patient bound by restraints must, under hospital policy, never be left alone.

But on this overnight, Carney’s emergency department was understaffed and didn’t have enough people for one-on-one monitoring. The sitter assigned to Gilberto was also watching two other patients, federal investigators later found. The investigators concluded that inadequate training and other lapses were “reasonable contributing factors” to the tragedy that followed.

This is what happened. Gilberto was left alone, tied down with Velcro straps, struggling to breathe.

Nobody noticed when his heart stopped. No one was there to raise an alarm. He died alone, in bed, in a bright blue-dot patterned hospital gown.

Nineteen hours after Gilberto entered a Steward hospital looking for help, his body was wheeled into the morgue.

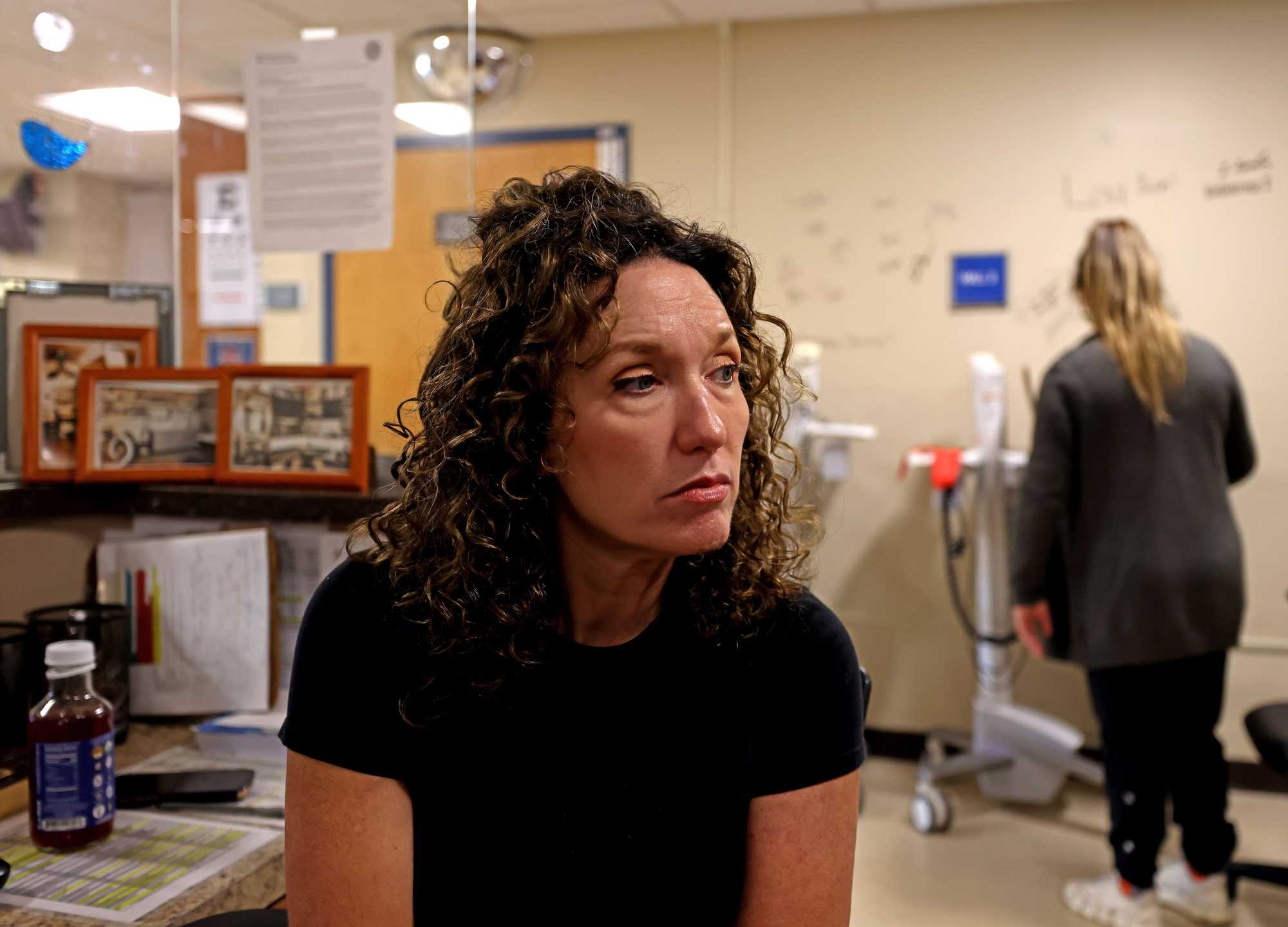

Emergency department nurse Kelly Miller sat at the nurses’ station on the last full day of operations at Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer on Aug. 30. Nashoba was one of two hospitals, with Carney the other, that Steward closed in Massachusetts recently. (David L. Ryan/Globe Staff)

A portrait of neglect

As Gilberto’s death painfully shows, those who run Steward Health Care did not have to put their hands on patients to do harm — they did it by starving the system of staff and resources.

At hospitals across the country owned by the nation’s largest private for-profit health system, countless surgeries have been canceled because unpaid vendors refused to deliver vital equipment. Time-sensitive medical tests, such as cancer biopsies, have been routinely delayed. Overworked staff members were regularly forced to scrounge for supplies, sometimes bringing items like toilet paper and pens from home.

All the while, the Boston-born company, led and largely owned by former Massachusetts heart surgeon Dr. Ralph de la Torre, prioritized expanding the chain and taking huge dividends for de la Torre and others.

The Globe first exposed Steward’s deadly failings in January with a report on the case of Sungida Rashid, a woman who died soon after giving birth at Steward’s St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton. Doctors there were unable to properly treat her because the hospital was out of a common medical device used to stem internal bleeding. The device was out of stock because Steward had been stiffing its vendor. And much more news about Steward has unfolded in the months since, including a bankruptcy filing, the recent deals to sell six of its hospital campuses in Massachusetts, and the closure of two others — one of them the beleaguered Carney.

But the full scope and tragic consequences of Steward’s mismanagement were still to be chronicled.

Nabil Haque and Sungida Rashid with their newborn daughter, Otindria, on the morning of her birth. (Nabil Haque)

Deaths like Sungida Rashid’s have occurred time and again at Steward hospitals.

The Spotlight Team identified at least 15 instances in which Steward patients died after failing to receive professionally accepted standards of care due to equipment issues or staffing shortages. This total omits deaths due to individual lapses in judgment or medical errors in order to focus on the real, systemic Steward scandal, the one driven by radical under-investment by management in hospitals that mainly serve patients on the lower end of the economic spectrum — often those most in need of care.

One died in the registration line at the Good Samaritan Medical Center emergency department in Brockton, on a day eight nurses were working when there were supposed to be 19.

Another died after forcing open a faulty window at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, and then leaping to his death, multiple nurses have confirmed to the Globe. He was in the hospital for fall injuries from an earlier suicide attempt.

At least 16 other patients suffered injuries in similar circumstances, the Globe probe found. And at least 2,000 more were found by federal regulators to have been put in immediate peril.

The Spotlight Team undertook a review of hundreds of government reports, staffing complaints filed by nurses, federal data, and wrongful death lawsuits. The investigation also relied on conversations with patients’ families and their lawyers and interviews with more than 100 current and former Steward workers.

Eleanor Gavazzi (left, waving flag) shouted at a rally advocating to keep Steward hospitals Carney Hospital and Nashoba Valley Medical Center open on the front steps of the State House in Boston on Aug. 28. Gavazzi said that Nashoba Valley Medical Center saved her son's and mother’s lives and that it would take her 40 minutes to get to an ER if it closed. (Andrew Burke Stevenson for the Boston Globe)

What emerged was a portrait of staggering neglect. Not by Steward doctors and nurses, most or all of whom were driven by the medical practitioners’ pledge to “first, do no harm,” but by business-side executives who plainly were not.

On the whole, the more than 30 hospitals Steward operated have been among the worst, the most troubled in the country over the last five years, according to several measures.

Between June 2019 and June 2024, federal inspectors who enforce hospital health and safety standards sounded the loudest-possible alarm against Steward at least 32 times — citing the company with findings of “immediate jeopardy,” a level of deficiency so serious it means patients have died, been injured, or put at grave risk. Such findings can threaten a hospital’s Medicare reimbursements, which effectively would kill a hospital.

Immediate jeopardy findings are rare; just 13 percent of 6,101 Medicare-certified hospitals received one in that same five-year span, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Yet about a third of Steward’s hospitals received an immediate jeopardy finding, a pace of failure nearly three times the national rate.

Beyond the immediate jeopardy cases, federal investigators have documented more than 300 deficiencies at Steward hospitals in the past five years, including 10 deficiencies calling out serious failures to ensure patient safety by Steward’s “governing body” — its leadership. Only one hospital chain had more such leadership deficiencies in that five-year span: Universal Health Services, which had 12, though it is several times bigger than Steward.

Deficiencies

150Source: Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Want to go deeper? Explore our database of deficicients at Steward facilities.

Liz Kowalczyk, Jessica Bartlett, Yoohyun Jung, and John Hancock/Globe Staff

Federal regulators identified more than 300 deficiencies at Steward hospitals in the past five years

Of those, nearly 80 were condition-level deficiencies, which represent a greater risk of harm or injury to patients than standard deficiencies. The ones posing the greatest and most immediate risk are labeled ‘immediate jeopardy.’ Click on the dots to see details about deficiencies at each Steward facility.

Further, Steward hospitals are also among the bottom-dwellers in CMS hospital quality ratings, which take into account death and readmission rates, patient experience, and measures of timely and effective care.

Steward’s corporate leaders were well aware of the shortages in staff and supplies plaguing its hospitals, according to company emails obtained by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and shared with the Globe, federal inspection and financial documents, and the statements of current and former Steward administrators, who addressed increasingly urgent concerns about unpaid bills to their corporate bosses.

Getting business done in a local Steward hospital, such as getting bills paid, was a major challenge because everything ran through corporate, Dr. Peter LaCamera, chief of the division of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, told the Globe.

“When it got to the point of putting heads through walls,” he said he would reach out directly to the number two person in the company, Dr. Michael Callum, executive vice president, and “plead” his case. That helped sometimes, LaCamera said, but there was always another problem looming on the horizon.

The COVID-19 pandemic tested all hospitals in innumerable ways, but Steward’s issues were a constant, before — and well after — the rise of the virus.

Internal Steward emails viewed by the Globe reveal high-level discussions about vendors going unpaid at least as far back as 2019. In January that year, Douglas Costa, chief operating officer of Steward Health Care Network, complained in an email chain among top executives:

“We have an incredible amount of vendor invoices and employee expense reports outstanding right now. We have vendors discontinuing important services to our members. I won’t even get into how much I’m floating on my personal credit card at this point in time. How can we fix this?”

That discussion included chief financial officer John Doyle, vice president of finance Jacob Frumkin, and Ruben King-Shaw, a former member of the Steward board of directors, who at that point was chief strategy officer. King-Shaw rejoined the board in 2022.

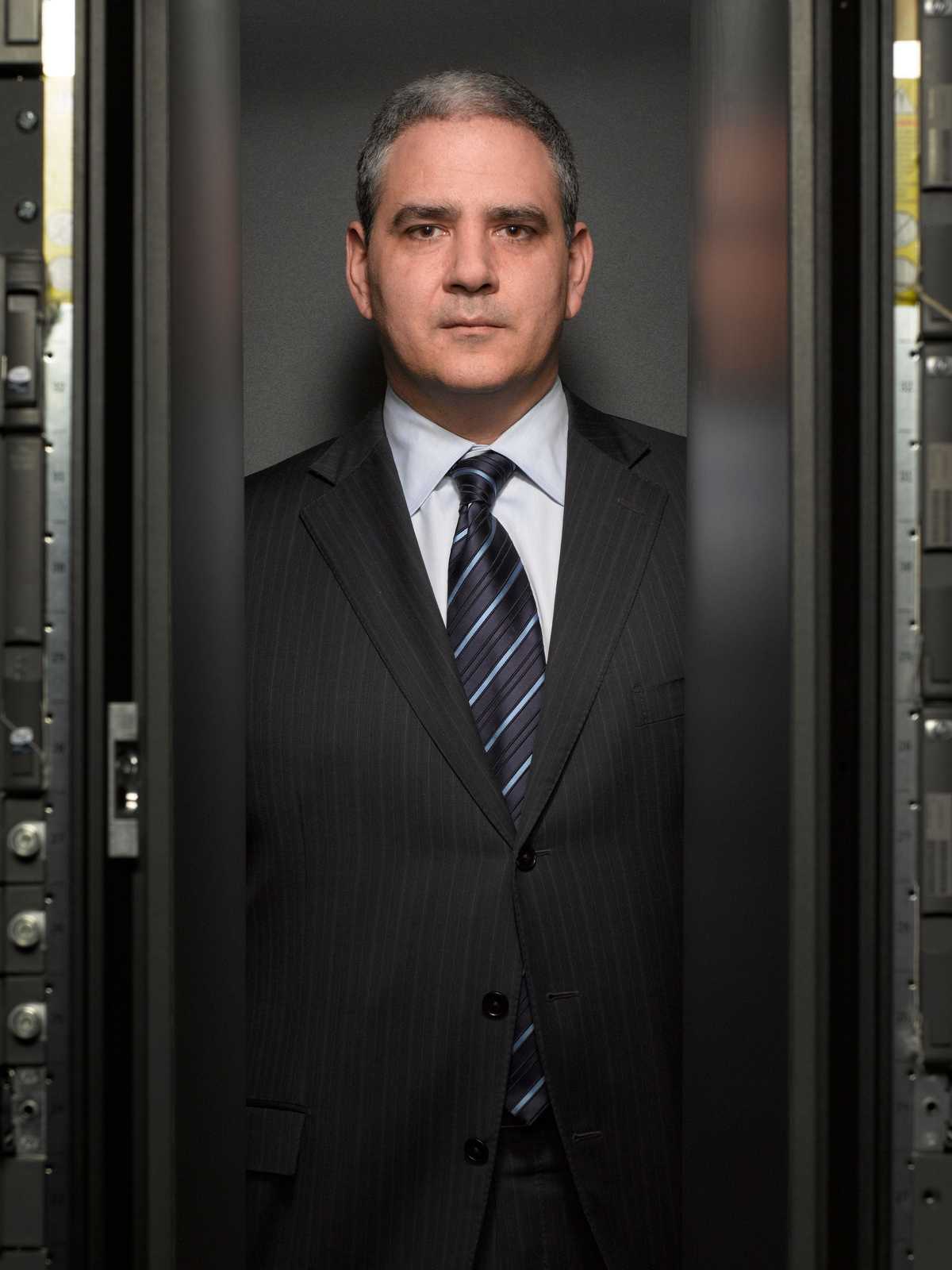

Dr. Ralph de la Torre had served as chief cardiac surgeon at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in 2005 before becoming CEO of Caritas Christi Health Care in Boston in November of 2008. (Wiqan Ang and Michael Lewis/Corbis via Getty Images)

In one specific 2019 case, the head of plant operations at Steward’s Jordan Valley Medical Center in Utah told federal inspectors he had warned corporate bosses that the vendor who provided salts for the water softening system — necessary to sanitize instruments — had threatened to stop delivery for nonpayment. His warnings went unheeded — and the vendor ultimately cut Steward off. During that time, surgical instruments were found to be contaminated, possibly leading to a patient’s infection. An employee informed hospital administrators: “Our list of credit holds by vendors is getting out of control. We will soon be in a position of not being able to acquire critical services.”

De la Torre and other Steward executives did not address a detailed list of questions sent by the Globe. “The company has no comment,” company spokeswoman Josephine Martin said in an e-mail.

The list of Steward’s failures goes on and on.

In December, a patient came to Steward’s Melbourne Regional Medical Center, in Florida, with stomach pain from a perforated bowel that needed immediate surgery. But after hours of waiting for a transfer, she died en route to another hospital 50 miles away because Melbourne, incredibly, had no general surgeon on call.

Early last year, administrators at Steward’s Holy Family Hospital in Methuen ordered staff to call patients with scheduled biopsies and tell them that their procedures — vital to early interception of cancers — had been canceled. The staff was told not to mention the reason: The company that provided the mobile testing equipment had not been paid.

Over the course of several years, St. Elizabeth’s, in an affront to basic human dignity, was out of “bereavement boxes,” the small cases used to carry the remains of deceased newborns, according to six employees, including three who said they lobbied for Steward to buy more.

Infant remains went to the morgue in bankers boxes, and when those ran out, in shipping boxes that nurses adorned with home-knit blankets and prayer cards.

“I remember seeing a very early demise, like about 17 weeks, and a nurse having to put the baby in this, just — supply box,” a Steward staff member told the Globe. “The nurses are amazing, they make everything look perfect. But it was the indignity of it.”

Paul C. Smith, president of St. Elizabeth’s, said in a statement to the Globe that he was unaware of “any situation where we did not have appropriate bereavement supplies,” and that he made these supplies a priority, “even if I had to help procure them myself.” Several of the staff members who confirmed the shortages also said that Smith, then chief operating officer, offered his personal credit card around 2019 to buy bereavement boxes.

An ambulance passed Glenwood Regional Medical Center in West Monroe, La. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Executive Pastor Tim Spencer watched rehearsal before Sunday service at First West Church in West Monroe on Sunday, Sept. 1. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

‘Would you pray for us?’

One sunny Friday last May, in the city of West Monroe, La., a massive human chain stretched around the brick mid-rise that houses Glenwood Regional Medical Center, the most troubled Steward hospital, data suggest. Some 400 people gathered at the facility, called by a local church to support a hospital in crisis. Medical workers in teal and navy scrubs stood hand-in-hand with area residents.

The prayer circle had been inspired by Glenwood’s staff, which was trying to keep their hospital afloat and their patients safe, while corporate bosses at Steward choked off operating cash and drove away employees who could only take so much.

“I heard staff members say, ‘Would you pray for us?’” said Tim Spencer, executive pastor of First West Church, which organized the prayer circle. “I heard it over and over again.”

This sort of public show of faith is wired into the DNA of northeastern Louisiana, sitting as it does midway along the southern Bible Belt. First West Church typically draws some 1,800 people for Sunday worship in an auditorium tiered like a Broadway theater.

The circle that morning was so large, organizers signaled prayer should begin with the bugle-like blast of a shofar, an ancient instrument made from a ram’s horn.

Heads bowed, the people of West Monroe prayed for Glenwood’s staff, for patients and their families, and they prayed that somebody with good intentions would buy their city’s hospital from the company that had led it to ruin.

Get the newsletter

Sign up to receive Spotlight reports and special projects in your inbox.

Glenwood should have fit neatly within Steward’s early visions for what the chain could be: a cheaper alternative to big-city teaching hospitals, a community provider that could serve people where they lived.

West Monroe, which depends on Glenwood, is in Ouachita Parish, a unit of Louisiana government similar to a county. The parish’s median household income is about $46,000, low even for Louisiana, one of the poorest states in the country. The US national median is about $75,000. Many in the parish earn their living in agriculture. Here, corn is a big crop, along with beans, cotton, rice, and timber, which feeds the local paper mill.

The hospital stands amid a cluttered row of fast-food franchises, one after another. It opened as a public hospital in 1962. Steward acquired it in 2017.

Livestock grazed in a field near Spearsville, La. A viewfinder at Black Bayou Lake National Wildlife Refuge in Monroe, La., on Aug. 29. (Craig F. Walker/Globe staff)

Jacob O’Briant and Amanda Easter enjoyed the music outside JAC's Craft Smokehouse on Trenton Street during Ouachita Live in West Monroe on Aug. 30. Country artist Timothy Wayne entertained the crowd during the free concert presented by Downtown West Monroe Revitalization Group. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

West Monroe High School junior varsity football players prayed after their game at Rebel Stadium in West Monroe, La., on Aug. 28. Mark Risinger filled his gas tank outside the Spearsville General Store in Spearsville, La. (Craig F. Walker/Globe staff)

Quickly, Glenwood became a focal point for Steward’s management failings: a one-star rated hospital that led the Steward chain in immediate jeopardy findings the past five years, with nine such violations. It is among the 10 worst hospitals nationally for immediate jeopardy citations, the Globe analysis shows.

As at many Steward hospitals, unpaid vendors placed Glenwood on credit hold, meaning the hospital struggled to get routine supplies, such as catheters and angioplasty balloons, pacemakers and surgical mesh, according to federal inspection documents. At one point this January, the director of radiology told federal inspectors that the hospital “cannot go much longer like this and that it will eventually fall like a house of cards.”

Staffing and supplies have been so short, state officials capped the 270-bed facility at 91 patients.

Inspectors documented 151 beds with broken nurse call buttons. Radiation safety badges worn by the radiology staff sat in the outgoing mail for months, not sent to a lab for testing. The vendor that sorted the mail had not been paid.

Not even Glenwood’s cafeteria was spared: The coffee vendor repossessed the coffee pots.

In the late summer of 2021, deadly, almost invisible mold spores took root in the lungs of some of the most vulnerable patients at Glenwood.

That September, the family of Theresa Williams visited her at Glenwood’s COVID ICU, seeing her only through glass. The 79-year-old great-grandmother, from a village outside West Monroe, was on a respirator, fighting for her life. She was known as a fancy dresser in high-heeled shoes, a good cook and seamstress who raised a family and then worked 25 years at a chicken processing plant.

Eleven days after Williams had been admitted, a fluid sample from her lungs tested positive for a mold known as aspergillus.

Aspergillus is generally not harmful to healthy people, but it is wildly dangerous to certain patients, including people who are immunocompromised. Under a microscope, the mold looks like a tree branch, specialists said, and that is how it grows, invading and essentially destroying lung tissue in its wake. Preventing aspergillus is one of the reasons hospitals sterilize and clean; a full-blown aspergillus infection is hard to treat and fatal in most cases.

Theresa was the fourth patient to contract an aspergillus infection in Glenwood’s COVID ICU in August and September 2021. The first three had already died, according to federal inspection reports. A fifth infection would be detected in early October. Federal records reflect no action by the hospital after the first infection, and still no action after the second.

“Two cases in the same unit would be very concerning,” Dr. Eric Dickson, CEO of UMass Memorial Health, who trained as a respiratory therapist, told the Globe. “It’s a rare disease, clusters are concerning and a second case would warrant rapid investigation.”

Joni Varnado displayed a photo of her late husband, David, at their son’s home in West Monroe, La. David, 61, died at Glenwood Regional Medical Center in August of 2021 during a mold outbreak in the COVID ICU. A doctor told Joni that David contracted a yeast infection in his lungs that went into his bloodstream. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Dr. Jeffrey Counts, an orthopedic surgeon in West Monroe, La., often had to cancel patients’ surgeries at the last minute because Glenwood Regional Medical Center lacked supplies and equipment. Numerous vendors had stopped delivering surgical supplies to the hospital because Steward Health Care was not paying them. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

But the understaffed Glenwood infection prevention department did not begin an internal investigation until the third case of aspergillus, losing two critical weeks, according to federal reports.

Steward later acknowledged the understaffing, conceding in government documents that “it had already been recognized” that Glenwood’s two-person infection prevention department needed more help. The company promised to hire an additional person. A high-ranking hospital employee told the Globe that Steward did add another person for a spell, but that the staff is now back to its 2021 level.

Glenwood also reported that the company it hired to clean the hospital lacked the right equipment to “properly clean in a healthcare environment.” The contract cleaners did not even know they needed to dust thoroughly, cleaning away the particles that can carry mold spores.

A former critical care doctor at Glenwood told the Globe that Steward’s lack of investment in the basics was to blame. “It harmed patients,” said Dr. Adebanke Vogt-Davis. “Aspergillus — I really think patients died because they had mold and fungus.”

Advertisement

Theresa Williams’s family knew none of this and never would have thought to ask. They had faith in the hospital. And then they got a call from Glenwood early on Sept. 27. Better get down here fast, the family was told. Theresa died that day at 9:42 a.m.

The Williams family only learned of the mold outbreak when a Globe reporter reached out last month.

The details about the mold infections, outlined in dire, damning terms in federal inspection reports, are publicly available, if tricky to find. They were shared with Steward administrators and executives. But no one told the affected families the extent of the outbreak. The federal reports do not name the patients. The Spotlight Team identified them by matching dates and other details to death records acquired by the team.

“The hospital didn’t mention anything about any mold,” said Chad Cappo, grandson of Patsy Strickland, 78, who died in the COVID ICU and whose death record matches the case cited in the federal report. “She was a hard-working, independent woman. … We miss her a lot.”

Chad Cappo talked about his grandmother Patsy Strickland, outside his home at Pelican Estates mobile home park in West Monroe, La., last month. The family said that nobody from Glenwood informed them about an aspergillus infection. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

A Glenwood doctor initially told the family of David Varnado, 61, that David was recovering from COVID, said his wife, Joni. Later, that same doctor reported that David had a “yeast infection” in his bloodstream. He was the first case of an aspergillus infection at Glenwood that summer. Joni knew nothing about the subsequent mold investigation, she told the Globe.

The abundant problems at Glenwood have put a question on the lips of many in West Monroe: How could it be that a company can just come into your community and ruin your hospital?

“They’re not selling swimming pool chemicals, they’re selling health care,” said the city’s mayor, Staci Mitchell, speaking of Steward. “If you want to run your pool chemical company like that, that’s your business. But this is people’s lives.”

In 2023, 10 medical leaders at Glenwood, including doctors who head major departments, wrote to the hospital governing board, saying that the company’s practice of not paying vendors was dangerous. They expressed “deep concern regarding current issues that we strongly feel are hindering our ability to render safe and effective care to patients.”

Mayor Mitchell said she personally interceded on behalf of a local landscaping business when Steward refused to pay it. Mitchell took the matter to Steward south regional president Josh Putter, and Steward ultimately paid the bill, she said.

Pent up rage at Steward bled through a hearing in April at the Louisiana State House. Debra Russell, an acute care nurse practitioner who worked 33 years at Glenwood before quitting last November, told lawmakers of the shortages plaguing the hospital, from a lack of cardiologists to life-saving drugs.

“It’s the saddest thing I’ve ever been around,” Russell said, softly.

Angry legislators learned that the regional president, Putter, was at the hearing and called on him to take some questions. He declined.

“Let the record show,” said the chair of the videotaped hearing, with frustration, “that the south regional president of Steward has refused to testify.”

With Putter watching and taking notes, a lawmaker asked Russell directly: “Based on what you’ve seen and your experience with Steward and their team, have people died because of [Steward’s] negligence?”

Russell flinched. She took a long pause, squeezed out a heavy breath, and responded in a cracked voice: “I don’t want to say yes. I don’t want to.” She paused again. “I’ve just seen too much.”

Mayor Staci Albritton Mitchell, in the council chambers at City Hall in West Monroe, La. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Dividends and debts

Steward was supposed to be a model of a new way of providing care, not the agent of this sort of neglect. Its driven and charismatic leader, Ralph de la Torre, had painted — promised — a vision of a new brand of community hospital: efficient, convenient, and more cost-effective. De la Torre was persuasive and he certainly had elite medical credentials: He had been one of Boston’s most esteemed heart surgeons, renowned for his devotion to the search for life-saving innovations.

De la Torre helped start Steward in 2010, when the Boston Archdiocese sold its chain of six Massachusetts community hospitals to Cerberus Capital Management, a New York private equity firm named for the three-headed dog in Greek mythology that guards the gates of hell. De la Torre, then CEO of the chain, stayed on as head of the new, for-profit company.

The new chain quickly expanded by gobbling up more community hospitals.

In 2016, Steward struck a company-defining $1.25 billion deal with Medical Properties Trust, a Birmingham, Ala., real estate investment trust. Steward would go on to sell its hospital land and buildings to MPT, and then lease the hospitals back, under a new “asset light” philosophy that purported to free up cash for hospitals to re-invest. This model, instead, adroitly converted physical assets into huge payouts for Steward’s owners and their investors, while saddling community hospitals with massive rent payments.

In 2017, Steward acquired the IASIS hospital chain, out of Tennessee, in a $1.9 billion deal that made Steward the country’s largest private for-profit hospital group.

Steward maintained its ambition to grow. De la Torre looked internationally for new opportunities, striking hospital operating deals in Malta and Colombia. Company emails obtained by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and shared with the Globe show Steward’s interest in expanding into Saudi Arabia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Montenegro, Georgia, Albania, and Croatia.

The former St Luke's Hospital, which was signed over to Vitals and later Steward on condition that it be redeveloped, was in a state of neglect and abandonment in Pieta, Malta. (The Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation/OCCRP)

Meanwhile, other internal Steward emails show executives juggling invoices from vendors, deciding which companies to pay and which bills to sit on.

“Why are we holding steris, globus, J&J, medtronic and boston sci?” a Steward executive wrote to the company’s vice president of finance, Frumkin, in April 2020, listing unpaid medical equipment vendors. “I think we need to be getting them something because they probably won’t supply us with materials for surgeries if we aren’t paying anything.”

The emails depict an invoicing dance as Steward officials lobbied one another over whom to pay and whom to put off.

Within a year, Steward executives bought out Cerberus for $335 million. After a decade of ownership, Cerberus departed with $800 million in profit, the company reported to Congress.

In January 2021, de la Torre and Steward’s remaining owners paid themselves $111 million from company funds, despite facing millions in vendor bills.

And, as the Globe has reported, while Steward sank into insolvency in recent years, it prioritized payments for private air travel and to a British private intelligence firm used to surveil and dig up dirt on company critics.

The enterprise collapsed in May. Steward filed for bankruptcy, seeking protection from about $9 billion in debt.

Steward’s financial problems have resounded from state houses and courthouses to the halls of Congress. De la Torre was subpoenaed to testify before a Sept. 12 hearing of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. On Wednesday, de la Torre signaled he wouldn’t testify, saying through a representative that testimony from him at this time would be “wholly inappropriate.”

There has been comparatively little public discussion of what has taken place beyond the corporate office, in the wards and hallways of the foundering chain.

Joan Shea sat with her husband’s guitar collection at her home in West Bridgewater. Michael Shea, 66, died at Good Samaritan Medical Center in Brockton. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Patients double-parked in hallways

The morning that EMTs rushed Michael Shea, 66, to the hospital, the emergency department at Good Samaritan Medical Center in Brockton was already drowning. It had been for months. Sick patients on stretchers were double-parked in a hallway, on the day after Thanksgiving, 2021. The harried staff was half-a-dozen nurses short. An inexperienced manager had to step in to care for Shea, who moaned in pain.

Mike Shea worked as a phlebotomist, but his real love was rock guitar, which he taught himself to play at age 12. By his 60s, he had collected 17 guitars, mostly electric, and was a regular musician on the Facebook site Riff of the Day, covering Aerosmith, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Jimi Hendrix.

He had received a terrible shock the month before in October, when he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. His oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute wasted no time planning Mike’s treatment.

Mike didn’t look ill, so he and his wife, Joan, decided not to immediately share Mike’s diagnosis with their four adult children. The Sheas’ eldest son was about to get married. Let’s tell the kids later, they decided. “The intent was not to have people sad at a wedding,” Joan said in a Globe interview.

Advertisement

Photographs from the reception show Mike on the dance floor, in a black tuxedo and scarlet bowtie, smiling wide enough to show off his dimples.

By Thanksgiving, though, Mike was painfully sick, too nauseous to attend dinner with his in-laws. After vomiting most of the night, he asked Joan to call an ambulance. He knew he needed hospital care.

EMTs took him to the closest one, Good Samaritan. It was a Steward hospital, struggling with the chain-wide pattern of corporate neglect that left it short of nurses, patient sitters, monitoring equipment, catheters, and even beds in the emergency department.

Mike was put on a stretcher in the hallway, connected to a heart monitor and intravenous fluids. A doctor told Joan that Good Samaritan planned to transfer Mike to Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, where, in partnership with Dana-Farber, he was receiving his cancer care. With a transfer imminent and no out-of-the-way place in the hallway for Joan to stand, she went home. It was about noon.

The doctor called Joan several hours later. Mike had “coded” and Joan “could come back to the hospital if she wanted,” Joan recalled.

She rushed back.

Nurses and doctors were pumping Mike’s chest and squeezing air into his lungs.

Joan clutched Mike’s hand. It was already cold.

A few minutes later, the doctor pronounced Mike’s death. It was about 4:15 p.m.

Joan sat stunned. All she could think to do was apologize — to her husband.

“I’m sorry I wasn’t there for you,’’ she spoke to Mike. She couldn’t understand what had happened. She had just been talking with him a few hours before.

Joan Shea displayed her wedding ring and one of her husband’s favorite guitars at her home in West Bridgewater. Mike and Joan Shea’s wedding photo (center) was displayed at their home. (Craig F. Walker/Globe staff)

The next month, the state’s largest nurses union took action, filing a complaint with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. The nurses reported that Mike had been discovered dead in the hallway.

Dana Simon, director of strategic campaigns at the Massachusetts Nurses Association, said nurses have for years fought with Steward over staffing levels. “What we heard incessantly for a decade,” he said, “from chief nursing officers and department directors and sometimes from hospital presidents is: ‘I can’t get approval from corporate for our staffing needs.’ "

In Mike’s case, nurses said the emergency department required 16 nurses that day; there were 11. The outcome “certainly may have been different if there was adequate nursing staff on to handle the number and acuity of patients that shift,” said Ann Marie Ryan, a nurse and union representative.

State public health officials investigated the union’s complaint the following January. They did not address Mike’s death in their findings, nor the death of another patient who arrived in the overcrowded emergency department that November, but they found the hospital at fault for lapses that included leaving critically ill patients with no nurse to care for them.

Joan was unaware of the nurse shortage or the union’s complaint until the Globe described them to her. The information helped nudge into place for her some puzzling aspects of Mike’s death. His death certificate listed his cause of death as cardiac arrest, and the time at 2:15 p.m., not 4:15, when the doctor pronounced the death in Joan’s presence.

Joan knew that cancer likely would cut short her husband’s life. But not so suddenly. Not without his children having a chance to say goodbye. And she would have never let him die as he did — in a crowd, and yet entirely alone.

‘It was so preventable’

Gilberto Melendez-Brancaccio, who died unmonitored in the Carney ED, is buried in a hilltop grave in Quincy. The cemetery plot had been intended for Gilberto’s grandmother, but the family didn’t have the money to buy another when Gilberto died.

Every so often, on quiet evenings after work, Gilberto’s aunt Catherina Brancaccio, who helped raise him, plays back voice messages saved on her phone. In Gilberto’s final message, months before his death, his trembling voice asks his “auntie” for medical advice in case “the worst happens.”

“I’m just doing all I can to maintain my sanity,” he says on the recording.

Months before Gilberto died, a San Diego staffing company had yanked its nurses from Carney and other Steward hospitals because Steward allegedly owed it $40 million. Carney scrambled to fill the vacancies, but the emergency department was dangerously short of staff the day Gilberto arrived, according to two people who worked at the hospital at the time.

Lead department secretary Maryanne Murphy wiped away tears after hugging a patient, Mike Clark, on the last day at the emergency department at Carney Hospital in Dorchester on Aug. 31. (Kayla Bartkowski For The Boston Globe)

“It was chaos,” recalled Stephen Wood, a longtime nurse practitioner at Carney.

“The death was absolutely devastating to everyone, because it was so preventable,” said Wood, speaking of Gilberto.

The hospital created new protocols after Gilberto’s death to tighten up the monitoring of psychiatric patients. Those included more frequent checks on patients under restraint. Yet the hospital never hired enough staff to implement these changes, Wood said. Mostly, the emergency department just pulled nurses from other units in the hospital, he said.

The staffing shortages persisted. In an internal email from September 2023, a Carney ED nurse described showing up for her shift to discover just four nurses for 25 patients. Furious, she threatened next time to sit in her car in the parking lot until more staff arrived. “This is seriously dangerous and no one should be expected to work like this,” she wrote.

Gilberto’s mother, who declined to be interviewed, is looking to force change in her own way. She filed a wrongful death lawsuit in Suffolk Superior Court against Steward and five medical professionals at the hospital, seeking justice for her loss. Her case, like much litigation against Steward, is frozen now in legal purgatory, stayed by the courts because Steward is in bankruptcy.

While Steward fights over debt and money, accountability is on hold.

Gordon Russell and Hanna Krueger of the Globe staff, and Khadija Sharife of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project contributed to this report.

Spotlight editor Brendan McCarthy can be reached at [email protected]. Feedback and tips can also be sent to the Boston Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected], or by calling (617) 929-7483. Mail can be sent to Spotlight Team, the Boston Globe, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

Credits

- Reporters: Liz Kowalczyk, Chris Serres, Jessica Bartlett, Elizabeth Koh, Mark Arsenault, and Yoohyun Jung

- Contributors: Gordon Russell and Hanna Krueger of the Globe staff, and Khadija Sharife of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project

- Editors: Brendan McCarthy and Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Craig Walker, Barry Chin, Kayla Bartkowski, David Ryan, and Andrew Burke-Stevenson

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editors: Kevin Martin and Leanne Burden Seidel

- Design: Ashley Borg, John Hancock

- Development and graphics: John Hancock

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Quality assurance: Meredith Stern and Michael Johnston

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Jenna Reyes, and Peter Bailey-Wells

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

© 2024 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC