(Photoillustration by Ashley Borg/Globe staff)

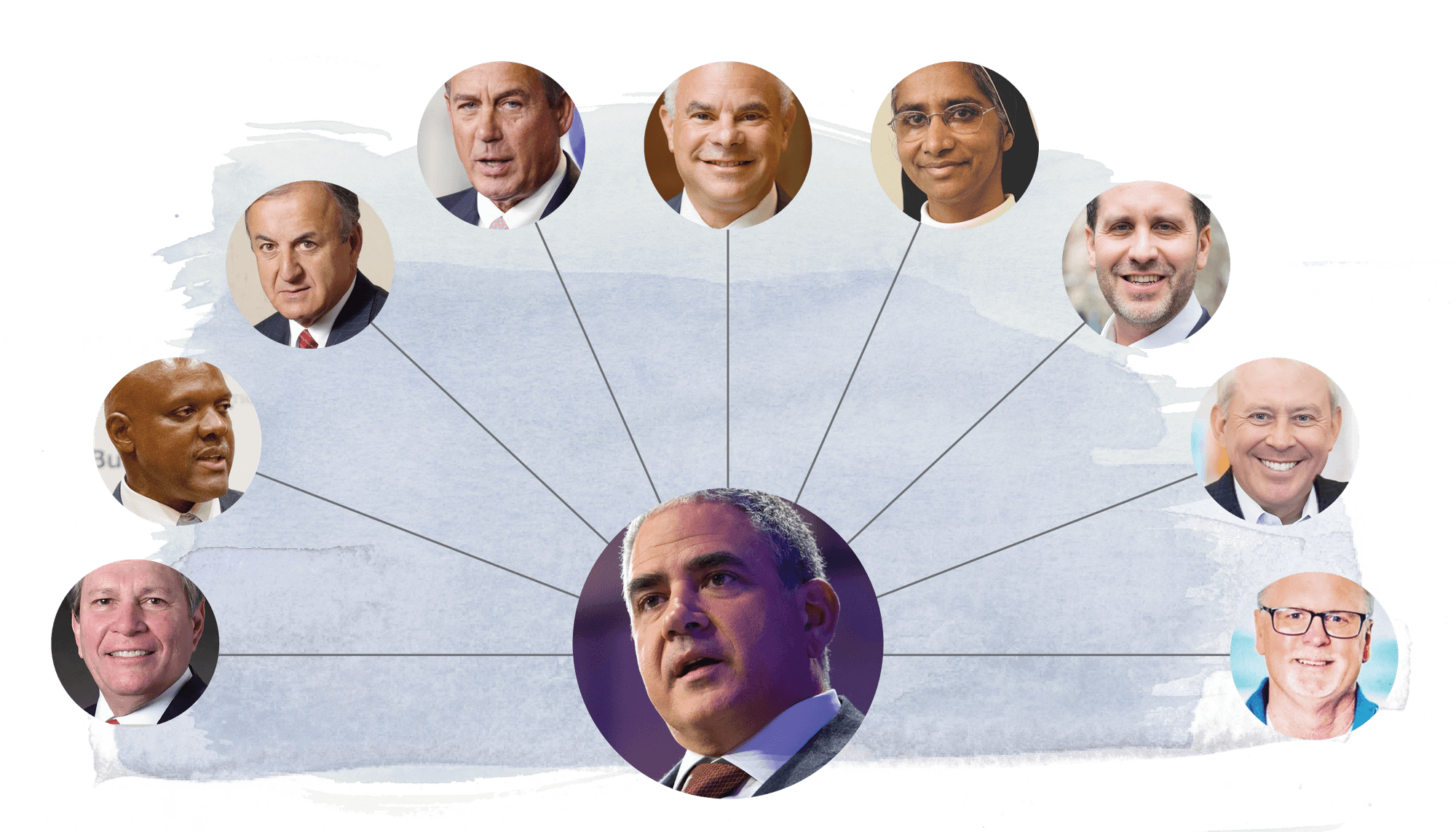

Ralph de la Torre oversaw Steward’s collapse. Meet the corporate board that OK’d many of his decisions.

When Ralph de la Torre resigned Tuesday from Steward Health Care, many of the nurses and doctors across the national hospital chain rejoiced and called it the start of a new era.

“It was about time,” said RaeAnne Hallahan, a longtime nurse at Holy Family Hospital in Methuen.

But the new Steward may not look all that different from the old one. Steward’s board of directors, in a step experts in corporate governance call highly unusual, eschewed appointing a successor to de la Torre, leaving the teetering health system without even an interim CEO or chairman. Now, Steward is led by that same board — and many of the same people — that seems to have offered little or no resistance as Steward’s hospitals were starved of resources and de la Torre got rich on massive dividends.

The board includes several top Steward executives and close de la Torre associates, as well as high-profile powerbrokers such as former US House speaker John Boehner and local real estate developer James Karam. Former Trump administration national security adviser H.R. McMaster served four years on the board before resigning in 2023.

All told, the group largely rubber-stamped de la Torre’s strategic vision for years and took home six-figure salaries for attending quarterly meetings. Several also benefited from de la Torre’s extravagant use of company funds on far-flung excursions, entertainment, and meals, a Globe Spotlight investigation has found.

Board members signed off on key deals supporting de la Torre’s aggressive for-profit model even as Steward slid toward financial ruin and patients’ lives were imperiled by staff and medical equipment shortages. Several joined de la Torre on his personal yacht to exotic retreats or dined with him at lavish restaurants, according to records obtained by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and shared with the Globe Spotlight Team. Some board members attended a European opera ball and went scuba diving together in the Adriatic Sea.

“This is a massive governance failure, because this board is clearly not leading,” said Douglas Chia, president of Soundboard Governance LLC and a senior fellow at the Center for Corporate Law and Governance at Rutgers Law School. “They are abdicating their duties.”

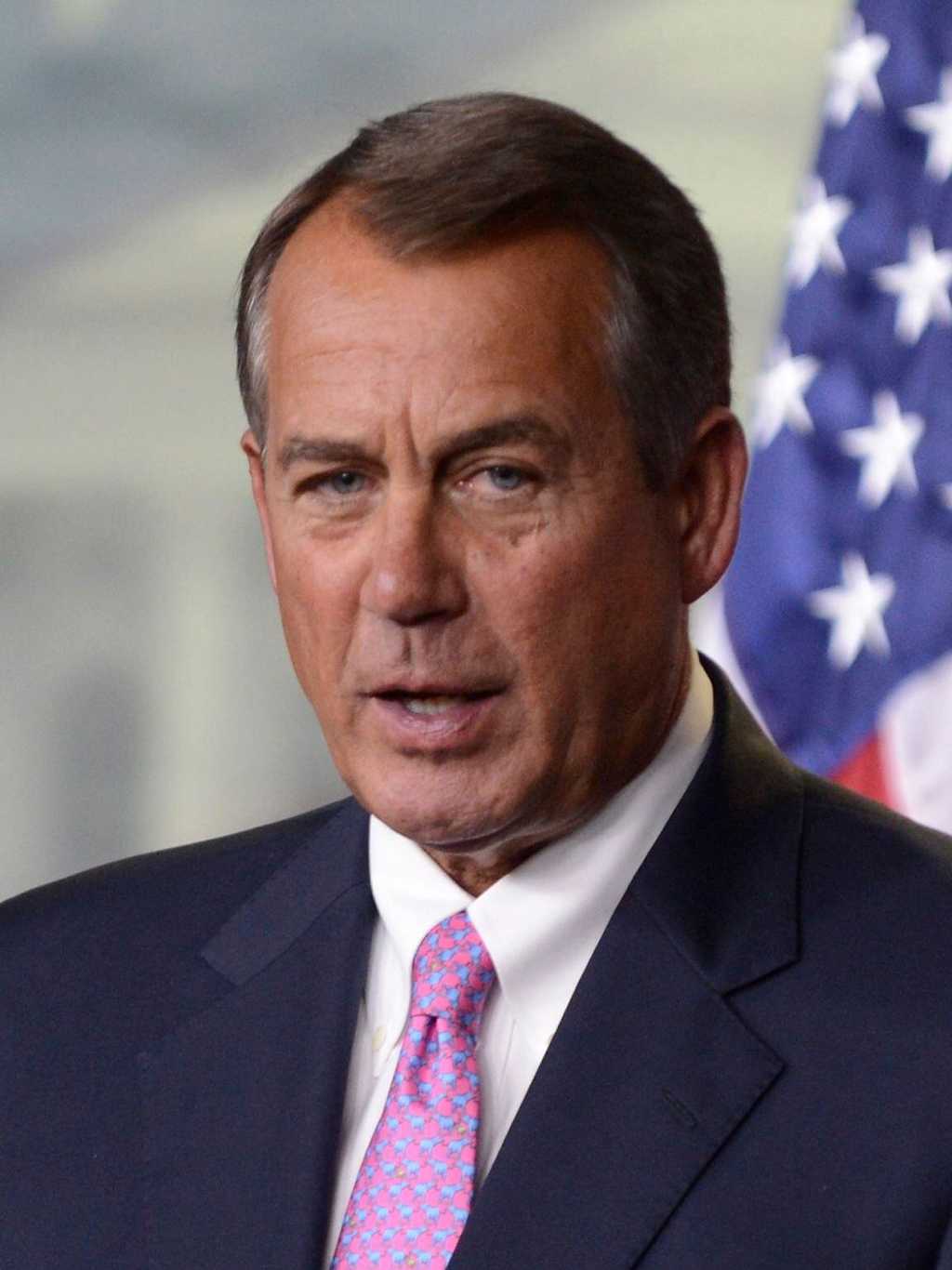

Then-House Speaker John Boehner on Capitol Hill in 2015. (NYT)

A federal grand jury in Boston has taken notice. Several board members have been summoned to answer questions from federal prosecutors or subpoenaed to appear before the jury, according to a person familiar with board operations.

The board’s inaction has alarmed many inside and outside the nation’s largest private for-profit hospital system, who point to it as a textbook case of corporate cronyism and the perils of insular boards.

“The board was overpopulated by sycophants who refused to speak up, ask questions, or take action,” said the person familiar with the board’s work.

Four corporate governance experts told the Globe that Steward’s board failed in dramatic fashion when it came to fulfilling its most fundamental duty: holding its chief executive accountable.

Advertisement

De la Torre’s mismanagement and blurring of corporate and personal funds should have prompted Steward’s board to fire him, they said, rather than allowing him to step down amicably. By itself, his refusal last month to appear before a Senate committee — in defiance of a government subpoena — marked a serious enough breach of his duties to remove him, they said.

“That’s a grave offense,” said Lawrence Cunningham, director of the John L. Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance at the University of Delaware. “If the CEO is unwilling to testify before Congress, I think the board should start looking for a new CEO.”

The Globe reached out multiple times, starting in July, to every person who served on Steward’s board in the last four years to ask about their oversight of the company. All of them either declined to comment or did not respond to interview requests.

Company spokesperson Josephine Martin declined to respond to several questions about the board. De la Torre declined to comment through his personal spokesperson, Rebecca Kral.

Public companies are required to have a board of directors. Though Steward is a private limited liability company, registered in Delaware, companies like this also typically have a board that oversees the managers of a business, provides a layer of oversight, and interacts with investors, experts said.

Current and former Steward Health Care board members

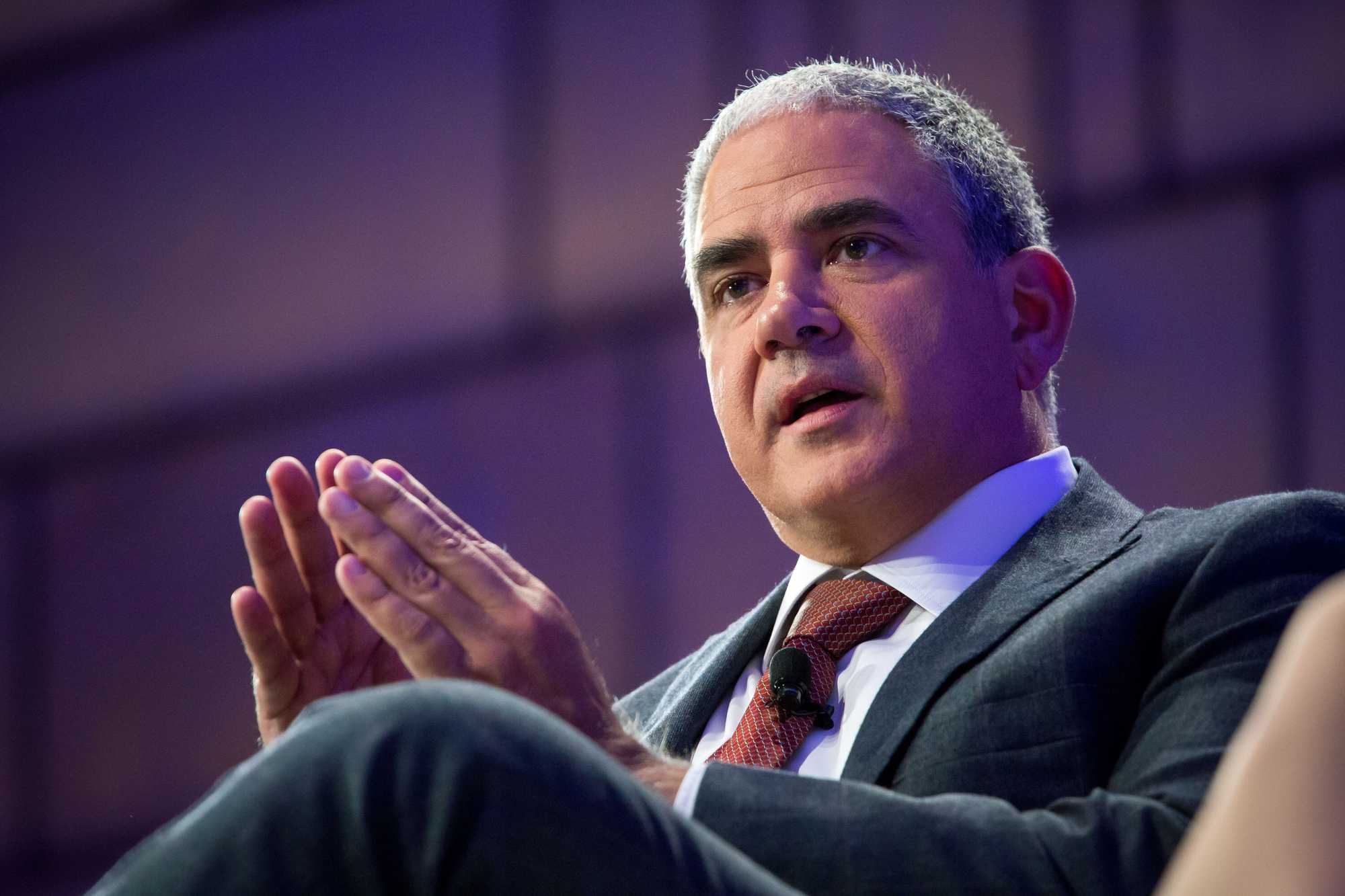

Ralph de la Torre

Former board member and former executive

De la Torre orchestrated the 2010 buyout that created Steward Health Care – becoming its chairman, CEO, and principal stockholder. He was formerly CEO of Caritas Christi Health Care and former cardiac surgery chief at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Carlos Hernandez

Hernandez is a retired CEO and former board member of Fluor Corp., an engineering and construction firm. He joined Fluor in 2007 as chief legal officer and retired from the company in 2020. He also serves on the board of the nation’s largest utility, PG&E.

Ruben King-Shaw Jr.

Steward executive

The former head of Florida’s health care agency, King-Shaw went on to serve as a high-ranking official of the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. He then held various roles at Steward, including, since 2018, chief strategy officer.

John Boehner

The longtime US representative from Ohio rose to become speaker of the House from 2011 to 2015. After resigning, Boehner joined Steward’s board in 2020. Boehner now works for the international law and lobbying firm Squire Patton Boggs, and serves on the board of a publicly-traded cannabis company.

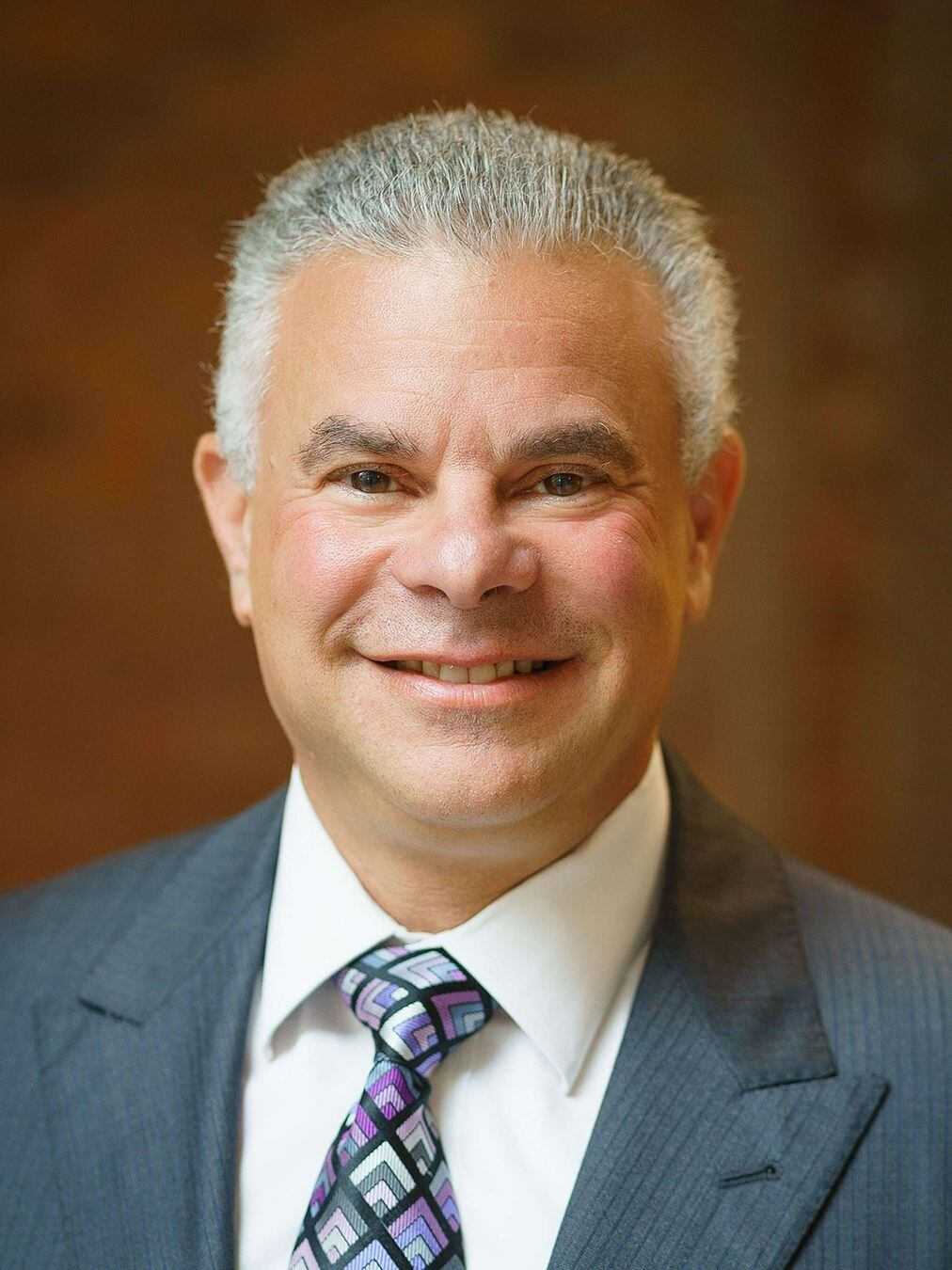

James Karam

Karam is president and founder of First Bristol Corp., a developer of retail shopping centers, office buildings, and hotels in New England. He served two stints as chair of the UMass board of trustees. He also served as chair of the board of Caritas Christi prior to its sale to Steward.

Michael Callum

Steward executive

Widely regarded as de la Torre’s deputy and confidante, Callum has held several roles at Steward, from Steward Medical Group president to executive vice president of physician services.

Sister Vimala Vadakumpadan

Sister Vadakumpadan started her career in the accounting department of Steward’s St. Anne’s Hospital in Fall River. She holds a master’s degree from Providence College, and has held a number of positions in the Dominican Sisters of the Presentation.

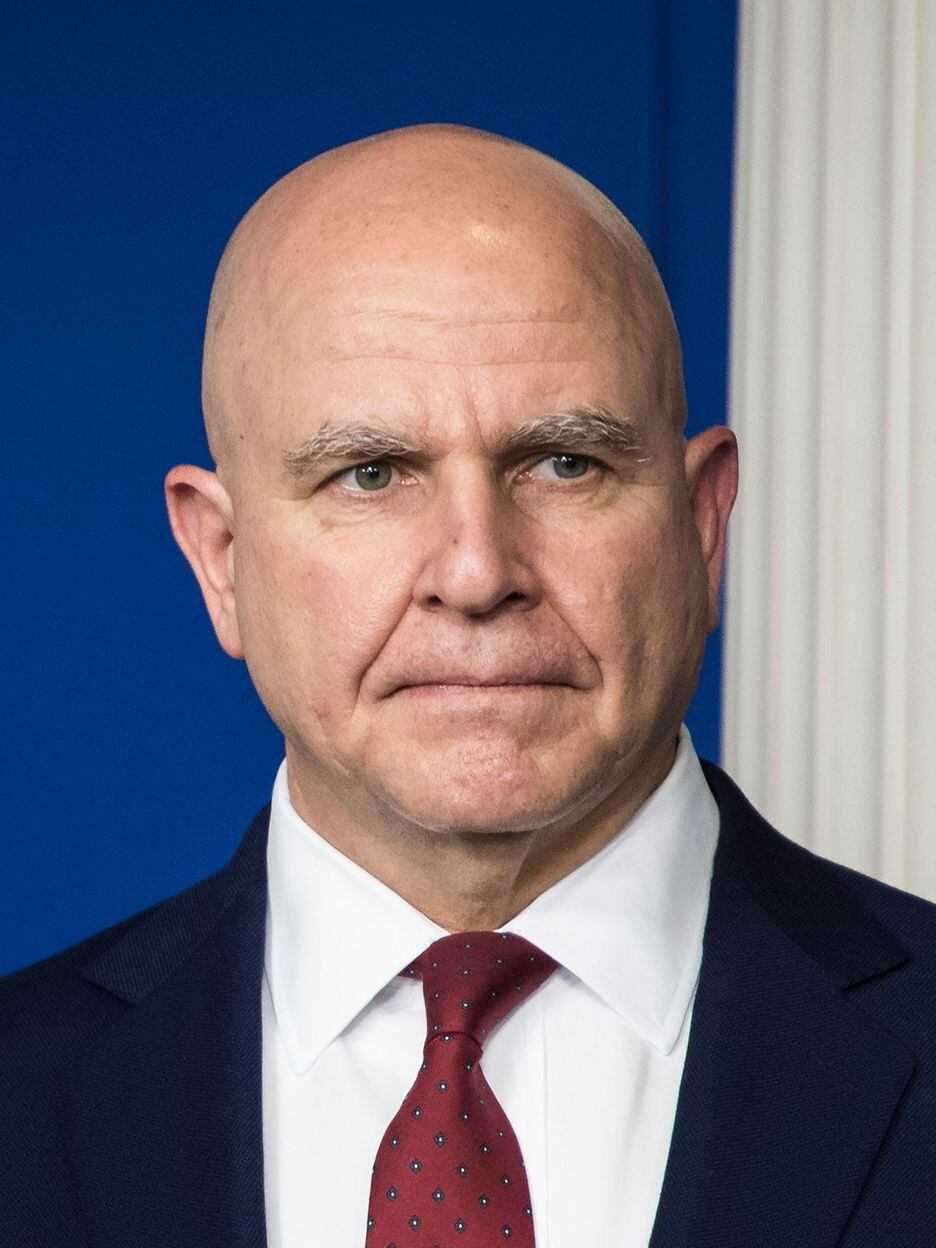

H.R. McMaster (Former member)

A retired Army lieutenant general who served in the First Gulf War, Iraq, and Afghanistan, McMaster was national security adviser to President Donald Trump from 2017 to 2018. He joined Steward’s board in 2019 and left in 2023.

Mark Rich

Steward executive

Rich played a key role in the 2010 acquisition of six Massachusetts hospitals that led to Steward Health Care. He was part of Steward’s original management team, and served in virtually every major operating role before becoming its president in 2023.

William Transier

Transier is founder and chief executive officer of a firm that provides advisory services to companies in financial distress. He was appointed as an independent manager to Steward’s board in January as part of a “transformation committee” overseeing the administration of Steward’s bankruptcy proceedings.

Alan Carr

Carr, an investment and restructuring expert, was appointed to Steward’s board as an independent manager in January as part of a “transformation committee” overseeing the administration of Steward’s bankruptcy proceedings. He has helped with other prominent bankruptcy cases, including Sears Holdings Corp.

Steward’s board was closely aware of the company’s inner workings in part because many members were company executives themselves. Corporate governance experts told the Globe that the executives were in a position to have outsize influence on a relatively small board and this is considered detrimental to independent oversight.

Among the company executives who served as board directors: Michael Callum, the company’s executive vice president for physician services; chief strategy officer Ruben King-Shaw Jr., a former high-ranking official with the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; and Mark Rich, the current president of the company. Sister Vimala Vadakumpadan, another board member, has been a longtime chairperson of the board of St. Anne’s Hospital in Fall River.

At one point last year, Steward executives, including de la Torre, held nearly half of the board’s nine positions. (The board recently added two directors, William Transier and Alan Carr, who are part of a “transformation committee” overseeing company matters related to the bankruptcy.)

The whole board was regularly updated on the company’s financial dealings, hospital budgets, and aggressive expansion plans, internal emails and board records show. Directors received multiple updates on international endeavors like Steward’s disastrous foray into Malta. In one 2021 board meeting, the Maltese operations were described in a PowerPoint as a “rapid success.” Today, Steward’s dealings in the island nation are part of a sweeping criminal corruption case being prosecuted there.

Dr. Ralph de la Torre, founder and former chief executive officer of Steward Health Care, in 2016. (Michael Nagle)

The board was also briefed on a massive $111 million payout to Steward shareholders in January 2021, according to de la Torre’s spokeswoman. That deal, in which de la Torre was the main beneficiary, too has come under scrutiny.

In other instances, directors received detailed briefings on and approved key Steward transactions, including its critical dealings with Medical Properties Trust, the Birmingham, Ala.-based landlord to which Steward paid hundreds of millions of dollars in rent.

During meetings, which typically occurred quarterly, the board was expected to review the company’s financials and advise management on risks to the company. For their part, board members received at least $125,000 to $250,000 a year from Steward, payouts, plus expenses and stock grants, documents show. By comparison, the median pay last year for non-employee directors in large companies listed on the Standard & Poor’s 500 index was $110,000, according to a recent survey.

Several directors reaped even more benefits from Steward’s largesse.

Callum and his spouse ventured off on a weeklong voyage on de la Torre’s yacht Amaral to Greece, Croatia, and Montenegro in 2022, according to internal emails. He and de la Torre were also aboard the Amaral the previous year to tour the Mediterranean islands of Sardinia, Corsica, and Monaco, capped by a night at the opulent Casino de Monte Carlo in Monaco.

Michael Callum

McMaster, the former Army lieutenant general and adviser to Donald Trump, was listed on an itinerary with his wife as guests on a five-day trip to Austria with de la Torre, an excursion linked to a Steward Health Care International board meeting. That trip included a visit to the Vienna State Opera ball and a performance at a Spanish horse-riding school. A 2023 excursion to the same ball — including a dozen tickets, private box, and hotel stay — cost approximately 120,000 euros, or roughly $130,000, according to emails shared with the Globe by OCCRP, a global journalism outlet.

McMaster, who stepped down from the board in 2023, declined through a spokeswoman in July to answer questions about his time at Steward. He was recently on a book tour and did not respond to additional requests for comment.

High-profile directors like McMaster and Boehner are often recruited by companies to build credibility and to attract new investors. Yet Steward appeared to use them to serve an additional purpose: making political connections to try to help secure lucrative overseas contracts.

Advertisement

McMaster, a decorated military commander who served in the First Gulf War, Iraq, and Afghanistan, used his rolodex of foreign connections regularly on Steward’s behalf. He brokered introductions for Steward executives to influential people, including the former US deputy national security adviser to Saudi Arabia, whom he called the “best connected person in the Kingdom,” emails show. Executives also prepped McMaster with talking points ahead of conversations with Malta’s prime minister and Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to the United States, according to emails reviewed by the Globe.

Steward executives gushed over Boehner’s and McMaster’s star power. Steward president Mark Rich referred to McMaster in one May 2021 email as “the friggin hero of the 1st Iraq War” and Boehner as a “republican non-Trump icon.”

“These are not men to be trifled with,” Rich wrote.

Then White House national security adviser H.R. McMaster (center) at a meeting in the Cabinet Room of the White House in 2017. (Alex Brandon/Associated Press)

Corporate governance specialists invoked a parallel between Steward’s board and that of Theranos, the disgraced blood-testing company that packed its board with eminent statesmen and high-powered politicians.

“Too often, people like Boehner and McMaster are invited into boards and become little more than symbols, or trophies to adorn the boardroom — instead of benefiting these companies with their insight,” said Wei Jiang, a professor of finance at Emory University’s Goizueta Business School in Atlanta. “Clearly that didn’t work in this instance. It’s a lot like Theranos.”

With Theranos, board members managed to avoid culpability by showing they were misled by a conniving CEO. That may be more difficult in Steward’s case if board members were privy to more detailed knowledge of the company’s dealings, said corporate governance experts.

The small size and tight relationships of Steward’s directors may have also hampered the board’s ability to check de la Torre’s management actions and personal excesses, experts said.

The boards of major hospital systems in New England far eclipse Steward’s in size. Mass General Brigham has a 22-person board, and Beth Israel Lahey Health’s board has 20 members.

The Steward board’s decision to forgo naming a successor to de la Torre, at least for now, reflects its ineffectiveness and detachment, experts said.

“Clearly no one is in charge,” Chia said. “This board was completely subservient to Ralph [de la Torre]. They were so checked out that when he was gone they didn’t even have a clue what to do.”

Larger boards have greater potential oversight capacity: They can bring in more independent directors with different perspectives and create specialized committees to monitor executive performance, pay, and internal controls, experts said. As recently as May 2020, Steward had just five directors on its board — a number so small that it’s shared by fewer than 2 percent of boards of large companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500 index, according to the Conference Board, a research firm.

“For a CEO who doesn’t want to be monitored, this kind of board structure would be a dream,” said Cunningham, the corporate governance expert.

Boards of private companies, like their public counterparts, can be subject to legal liability for failed oversight of company affairs, particularly if they have ignored red flags, the legal and corporate governance specialists told the Globe. Investors and creditors are among the parties that could sue boards for serious breaches of their responsibilities, they added.

Advertisement

Fifteen current and former company officers and directors have already incurred legal fees and expenses because of the ongoing investigations into Steward, the company disclosed last month in a bankruptcy filing. Steward sought a court order to allow insurance policies to cover those expenses, saying those investigations “have required, and will continue to require” those officers to pay legal fees.

“These board members need to be thinking seriously about what their personal liability might be,” said Todd Haugh, a professor of business law and ethics at Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business.

Lawsuits against company boards used to be rare, in part because the bar for bringing them was especially high. That changed in 2019, when a Delaware court allowed shareholders to sue ice-cream maker Blue Bell Creameries’ board after a listeria outbreak killed three people and caused the company to recall its products. Since then, more claims against directors have survived court challenges, putting boards on notice that they can’t turn a blind eye to clear evidence of malfeasance.

In the last few months Steward’s board has continued to meet, sometimes even weekly.

The meetings have traditionally started with Vadakumpadan, the Dominican Sisters of the Presentation nun and longtime board director, leading the group in reflective prayer. Often this year, the prayers have been for “strength and hope,” according to records reviewed by the Globe.

But in late April, Vadakumpadan opened the meeting with an invocation for something different: “humility and surrender.”

A week later, Steward filed for bankruptcy.

Mark Arsenault, Jessica Bartlett, and Hanna Krueger of the Globe staff, as well as Khadija Sharife of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, contributed to this report. Spotlight editor Brendan McCarthy can be reached at [email protected].

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporters: Chris Serres, Elizabeth Koh, Brendan McCarthy

- Contributors: Globe reporters Mark Arsenault, Jessica Bartlett, Hanna Krueger, as well as Khadija Sharife of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

- Editors: Brendan McCarthy, Mark Morrow, Gordon Russell

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photos: Doug Mills/New York Times, Michael Nagle/Bloomberg, Alex Brandon/Associated Press, Jabin Botsford/Washington Post, and Michael Reynolds/EPA

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Kevin Martin

- Design: Ashley Borg and John Hancock

- Development and graphics: John Hancock

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editor: Mary Creane

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC