Donna and Joseph Knight at their home in Middleborough. On Sept. 13, 2023, their daughter, Jennifer, collapsed and died in the registration line at Good Samaritan Medical Center after she told a nurse that she was suffering from chest pain and was having trouble breathing. The Knights are still seeking accountability for her death. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Softened reports. Lax oversight. How state officials enabled Steward’s rise and fall.

The phone call to Steward Health Care chief executive Ralph de la Torre from the state’s top health official came days after a veteran nurse at Steward’s Good Samaritan Medical Center was fired for a devastating lapse — one that a federal investigation later deemed a violation of basic care.

On Sept. 13, 2023, a triage nurse in the Brockton hospital’s overwhelmed emergency department received a plea for help from a patient in the registration line. Suffering from acute chest pain and shortness of breath, 37-year-old Jennifer Knight believed she was having a heart attack.

But 10 hours into her nonstop shift, with too few nurses to handle a surge of patients, the nurse sent Knight back to the line, without evaluating her or checking her vital signs, according to investigators. Knight collapsed just 20 minutes later and died.

That decision, and the tragedy that followed, led to the nurse’s termination weeks later, according to hospital records, and prompted an immediate protest from the nurses union.

The response from the Healey administration was also swift. Secretary of Health and Human Services Kate Walsh reached out directly to Steward’s CEO. In that call, she didn’t focus on the fatal lapse in care. Rather, she had a request.

Walsh wanted de la Torre to rehire the nurse, Holly Zachos, whose husband, George, is also a top state health official under Governor Maura Healey. Walsh made it clear the request came from Healey’s office, that Zachos had ties to the administration, and that Steward should retrain Zachos after rehiring her, according to two people briefed on the matter.

The call — which circumvented any official appeal process — occurred at a time when Steward was careening toward bankruptcy, and seeking millions in bailout money from the Healey administration. Within days, Zachos was back on the job.

Explore more

- Death, indignity, despair: The human cost of Steward’s neglect

- How Steward’s CEO used corporate funds as the company crumbled

- How a real estate firm grew with Steward, keeping its shaky finances secret

- Meet the corporate board that OK’d many of de la Torre's decisions

- Steward raided the coffers of its in-house malpractice insurer

The Globe Spotlight Team learned of the exchange through documents and sources close to the matter, who said they considered it a clear request for a political favor. Healey, Walsh, and George Zachos declined repeated interview requests. Just prior to publication of this story, Healey’s office acknowledged the phone call and that the request took place, saying her office intervened because the administration believed the nurse’s firing was unjust.

In a statement, Walsh said she had good reason to make the call. “When a patient dies in a hospital, it is almost never one person’s fault,” the statement read. “This tragic death at Good Samaritan Medical Center might have been avoided had Steward Health Care invested in quality and safety in their facilities.”

The direct ask of de la Torre, and his rapid response, is one of the most telling examples of the often-accommodating relationship that long persisted between Steward executives and state regulators.

While de la Torre and other Steward executives have faced withering scrutiny for their alleged mismanagement and plundering of one of the nation’s largest private, for-profit hospital chains, the Globe Spotlight Team has found they benefited from insufficient scrutiny from elected officials and regulators until the company foundered and it was too late.

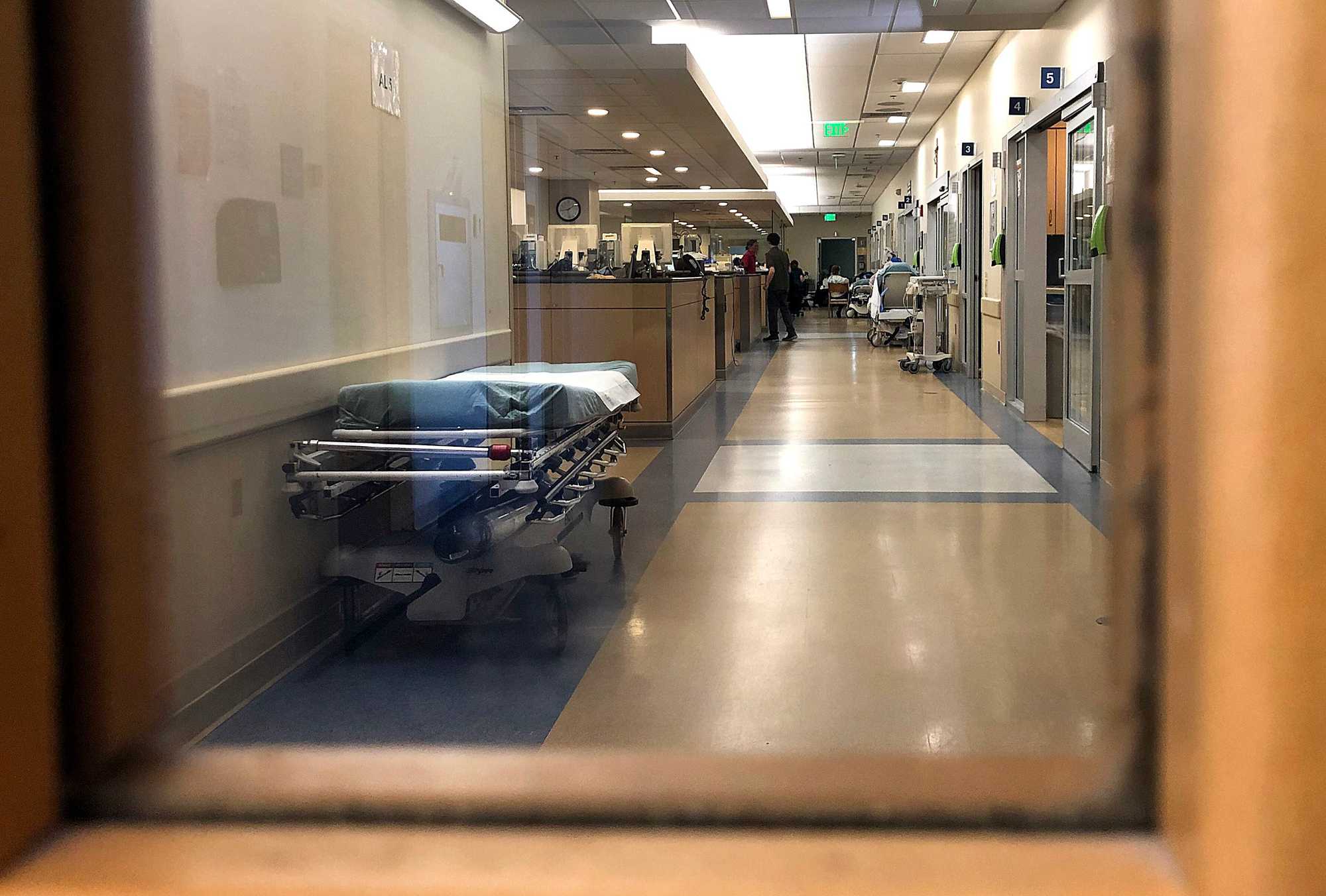

The emergency department at Good Samaritan Medical Center in Brockton, which has been cited multiple times by regulators for unsafe conditions. On Sept. 13, 2023, patient Jennifer Knight arrived at the hospital suffering from acute chest pain and shortness of breath. Yet a nurse sent her back to the registration line without evaluating her or checking her vital signs, according to investigators. Knight collapsed just 20 minutes later and died. (John Tlumacki/Globe Staff)

Advertisement

From nearly the moment of Steward’s founding in 2010, Massachusetts officials failed to discipline the Boston-born hospital chain for regulatory violations, check its aggressive expansion plans and relentless cost-cutting, or respond forcefully to dire warnings as it spiraled toward financial collapse, the Spotlight Team has found. Critical reports were softened, alarming financials went unheeded, and broken promises by Steward were unpunished. These failures spanned multiple administrations and contributed to a crisis that has harmed communities and cost lives.

Time and again, Massachusetts health regulators acquiesced to Steward’s demands even as Steward flouted state laws. Handed a loose rein, Steward’s executives rode the hospital chain right into bankruptcy.

Among the Spotlight Team’s findings:

- A top state health official directed a subordinate in 2015 to remove information about serious patient care problems at Steward from a public presentation.

- Then-Attorney General Healey’s office, which had substantial sway over health care companies, reworked a 2015 report about Steward to downplay its perilous financial condition — to the surprise of one of the report’s lead authors.

- State health officials ignored repeated pleas from Steward nurses, including Zachos, to force significant improvements at besieged hospital units, where patients languished, and in some cases died, after receiving inadequate care. At the same time, they did little as Steward eliminated critical-care beds to focus on more profitable services, closed key medical units without legally required notice, and kept its growing financial problems from public view. Steward repeatedly claimed that its finances were proprietary, and thus exempt from the disclosures required of every other hospital system.

- At pivotal moments, Steward executives pushed employees and their families to donate generously to key players on Beacon Hill and beyond, filling the campaign coffers of their would-be regulators. All told, executives and their spouses gave at least $2.4 million to federal and state candidates — largely in states targeted for hospital expansion, according to a Spotlight review of campaign finance databases.

Some of the elected officials now most vocal about Steward’s implosion collectively took in hundreds of thousands in campaign dollars from its executives and employees.

Maura Healey is among them.

This summer, Healey slammed de la Torre for fleecing hospitals, calling his actions “really reprehensible and unforgivable,” and suggesting he had fooled the state.

“He basically stole millions out of Steward on the backs of workers and patients,” she said. “Our administration is working night and day to protect jobs, protect patients, and pick up the pieces of the situation that Ralph de la Torre has put us in.”

The administration, in response to questions from the Globe, highlighted several steps it took this year to demand financial transparency from Steward and to pressure the company to transfer ownership of the hospitals.

But over her 10 years in statewide office — first as attorney general and now as governor — much more could have been done, regulatory experts said. She has had as much power as anyone else to regulate the chain.

Just months after she became attorney general in 2015, Healey’s office said Steward had fulfilled its obligations under a state oversight agreement in place since the company’s founding. Yet, the chain’s financial projections portended grave problems. As governor, Healey’s administration was briefed in the summer of 2023 about Steward’s likely collapse, records show. There’s no evidence the administration took significant action in response to the warning, the Spotlight Team found.

Health and Human Services Secretary Kate Walsh (left) and Governor Maura Healey, following a ceremony at St. Anne's Hospital in Fall River on Nov. 19. Healey and Walsh have come under criticism from front-line nurses and others for not taking more aggressive action to discipline Steward Health Care for regulatory violations and to demand improvements at its hospitals, where patients languished and, in some cases, died after receiving inadequate care. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Advertisement

The crisis began to unfold publicly in 2023, but state officials that year didn’t send in monitors to protect patients, nor did they negotiate with other providers to take over Steward’s hospitals — actions that, regulatory experts and hospital workers said, might have saved lives.

“What we witnessed with Steward was not state regulation — but the charade of regulation,” said Alan Sager, a Boston University professor of health law, policy, and management. “Everyone just went through the motions.”

So, when it comes to a quick and forceful state response, the call to de la Torre stands out.

Word of the state intervention gradually spread. In addition to the three people briefed on the details of Walsh’s phone call, several Steward nurses, as well as company insiders, independently told the Globe they were made aware that Healey’s administration had stepped in.

Julie Pinkham, executive director of the Massachusetts Nurses Association, told the Globe that after Zachos’s firing, she called Walsh directly to demand the nurse be rehired. Two hours later, Pinkham said, Walsh called back and said she had spoken to de la Torre directly and that Zachos would get her job back.

Holly Zachos declined to be interviewed. She and her husband said in written responses that they didn’t reach out to the Healey administration about her firing. The nurses union said Zachos, a union steward, was scapegoated because she was a longtime critic of hospital management.

A Steward spokeswoman declined to comment, and a representative for de la Torre, who left the company on Oct. 1, also didn’t comment.

The company, now based in Dallas, is at the center of a federal criminal investigation into alleged fraud, bribery, and corruption. Last month, federal agents separately served de la Torre and Armin Ernst, a Brookline resident who leads Steward’s international entity, with search warrants and seized their phones, the Globe has reported.

The consequences of Steward’s financial straits were first exposed in a January Globe report about Sungida Rashid, a 39-year-old woman who died after giving birth at Steward’s St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton. Doctors there were unable to treat her because the hospital ran out of a common medical device to stem internal bleeding. The device was out of stock because Steward hadn’t paid the vendor.

Sungida Rashid, 39, died after giving birth in October 2023 at Steward’s St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton. Rashid bled to death when the hospital ran out of a common medical device to stem internal bleeding. The device was out of stock because Steward had not paid the vendor. Here, Rashid was holding her newborn daughter, Otindria, the morning of her birth. (Nabil Haque)

A follow-up Spotlight investigation uncovered at least 14 other deaths here and across the country of Steward patients who didn’t receive professionally accepted standards of care. Hundreds were injured or put at risk because hospitals lacked enough staff or adequate supplies.

In the wake of these incidents there were calls from front-line hospital employees to hold Steward accountable, but they were weakened by a revolving door of regulators — some of whom came directly from Steward’s management ranks. In one case, a Steward hospital executive left to become the state’s top health official, a role in which he allegedly pressed for new regulations that benefited Steward’s expansion plans, according to an email reviewed by the Globe, a former state official, and allegations filed in a civil suit. And then he returned to Steward.

“The state had zero response to Steward’s greed and charlatan way of operating,” said Dr. Paul Hattis, a senior fellow at the Lown Institute, a Brookline health care think tank. “They were clearly not up to the challenge.”

The Spotlight Team reached out to Healey’s office in late November and sought interviews with the governor, Walsh, and George Zachos, executive director of the Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine and the husband of the fired nurse. Each declined the request.

Healey’s office emailed the Spotlight Team a statement Wednesday night.

“The Attorney General’s Office under AG Healey exercised all power and authority it had to monitor Steward Health Care System and report publicly on their financial situation,” the statement read. Healey’s office noted she defended the state as attorney general when Steward sued to withhold its financial statements.

Walsh, secretary of Health and Human Services, said the administration has always focused on protecting access to care, preserving jobs, and stabilizing the health care system. She said her call seeking Zachos’s reinstatement was motivated by her determination to do ”what I know to be the right thing — not only for this individual nurse, but for the hospital as a whole.”

Dr. Robert Goldstein, the commissioner of the Department of Public Health, said that the administration had few options in responding to Steward’s violations. The department could “deny them future expansions or take away their license completely,” which could leave patients without medical care, he said. “Regulations are black and white and we are operating in a very gray space.”

Two months ago, the Globe sent half a dozen records requests for documents, emails, calendars, and any communications from around the time Walsh called de la Torre. The state provided limited records but has not yet completed any of the requests.

Promises broken, warnings ignored

Signs of trouble emerged early in Steward’s history — and were all but ignored.

When Steward bought the Caritas Christi chain of six Massachusetts hospitals in 2010, buoyed by a huge infusion of private equity capital, top executives made a series of promises to then-Attorney General Martha Coakley. They pledged not to close or sell any of the hospitals for at least three years.

After it acquired more hospitals, Steward promised to maintain the same scope of services at two — Quincy Medical Center and Morton Hospital in Taunton — for the next 10 years.

Former Steward Health Care chief executive Ralph de la Torre at a meeting at Norwood Hospital in 2009. The embattled executive recently resigned as head of Steward and is now the target of a federal corruption probe. (John Tlumacki/Globe staff)

Steward soon broke those promises.

In the summer of 2013, Steward closed Morton’s pediatrics unit. Then on the day after Christmas in 2014, Steward closed the 196-bed Quincy hospital altogether — making Quincy the largest Massachusetts city without an acute-care hospital. The abrupt closure violated a state law requiring 90 days’ notice.

The state, resisting public pressure, took no legal action to hold Steward accountable.

By then, Steward’s financial condition was rapidly deteriorating. The company’s annual net loss more than tripled from 2012 to 2014, while its cash reserves were severely depleted, state records show.

Yet Steward’s escalating troubles did not prompt heightened scrutiny. In early 2015, staff under then-Attorney General Healey began analyzing Steward’s compliance with the terms of its takeover of Caritas. They concluded in a now-controversial report that Steward had fulfilled the obligations it agreed to in 2010.

One of the report’s lead authors was surprised by its favorable findings — and now says Healey’s office softened the report’s portrait of Steward’s dismal finances.

Nancy Kane, a management consultant and then-health policy professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, was hired by Healey’s office to analyze Steward’s financial health. What she found was unsettling: After years of staggering losses, Steward was teetering toward insolvency. The company’s cash balances had eroded while its unfunded pension and debt obligations had mushroomed. By 2014, the company had a net worth of negative $185 million. Its total liabilities exceeded $1.4 billion, she found.

“It was clear then that they were in deep financial trouble,” Kane told the Globe.

Then-Attorney General Maura Healey (center) met with staff at her office in Boston in September of 2015. (Jessica Rinaldi/Globe Staff)

Kane said she was also alarmed by another finding: That despite losing tens of millions of dollars a year, Steward in 2013 had disbursed $30.9 million to top executives in the form of loans secured by the company’s stock. To Kane, the distribution was alarming, in part because Steward leaders had committed not to extract payouts for at least three years after the Caritas deal.

“That really disturbed me at the time because it showed that Steward executives were already taking out large amounts of money to pay themselves,” she said in an interview. “My first thought was, “Whoa, I don’t trust these guys.’”

Yet when Healey’s office sent her revisions to the report, Kane said, she found her language had been softened to downplay Steward’s precarity. Kane worked under a confidentiality agreement and is unable to provide copies of the report.

The report went through “endless rewrites,” she said, in which Healey’s staff would insist on more upbeat language. The $30.9 million payout was relegated to a footnote. Kane believes it deserved more prominence.

“They kept editing [the report] to make it look happier,” Kane said. “I kept saying, “No, no, it’s not happy. They have loads of debt.’”

In a statement to the Globe, Healey’s office said the 2015 report “was clear about Steward’s financial problems.”

Advertisement

Rewriting the law, to Steward’s benefit

The muting of Kane’s findings fit a pattern. When state employees and health finance experts pointed to violations of the law and cracks in Steward’s facade, state regulators deflected the warnings or accepted the hospital chain’s excuses.

And as the more stubbornly skeptical regulators learned, Steward typically got what it wanted.

In 2014, Steward wanted to open a cardiac catheterization lab for diagnosing heart problems at its Fall River hospital, Saint Anne’s. But the state, aiming to avoid a medical arms race, had forbidden hospitals from opening such labs within a 30-minute drive of an existing one. Competitor Southcoast Health had a cath lab less than two miles — or about an eight-minute drive — from Saint Anne’s.

But Steward had a key ally: John Polanowicz, the then-state Health and Human Services secretary who had recently left his position as president of Steward’s flagship hospital, St. Elizabeth’s. Polanowicz allegedly encouraged officials in the Department of Public Health, which he oversaw, to rewrite the rules, which later allowed Steward to build the heart center.

Governor Maura Healey unfurled a Saint Anne's Hospital Brown University Health banner, covering the former Steward Family Hospital sign, during a ceremony at the Fall River hospital last month. The event marked Brown University Health’s acquisition of the former Steward hospital. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Former Steward executive John Polanowicz, pictured here in 2014, left his position to become the state’s top health official. While in office, he allegedly pressed for new regulations that benefited Steward’s expansion plans. Polanowicz denied giving the company preferential treatment. (Joanne Rathe Strohmeyer/Globe staff)

Deborah Allwes, a former health department official, said the exception was specifically tailored to benefit Polanowicz’s former — and future — employer.

In response to questions from the Globe, Polanowicz said that Allwes was “mistaken” and that the new rules were based on research about the safety of cardiac catheterization and “not to benefit any one hospital or system.”

Polanowicz said he always acted ethically while health secretary. “I did not advocate for Steward while EOHHS Secretary. I did not help the company get permission to build a cath lab,’ he said.

The favorable treatment of Steward continued, the Globe found.

In a 2016 deposition, Allwes said she was ordered by then-Public Health Commissioner Dr. Monica Bharel to remove data from a public presentation on a different matter that portrayed Steward in “a negative light.” Allwes said she had to alter slides in her presentation to omit descriptions of patient harm in Steward hospitals — incidents known as “serious reportable events,” according to the deposition taken in a Southcoast lawsuit against the health department over the cardiac catheterization issue.

Soon after, Allwes said she was scolded by Bharel, an appointee of Governor Charlie Baker, for not giving Steward adequate time to review her presentation and provide feedback on it, according to the deposition, portions of which were obtained by the Globe. Then, at the last moment, state health officials falsely claimed that Allwes was sick and unavailable to make her presentation, a move that prevented her work from immediately reaching the Public Health Council, a regulatory body chaired by the commissioner, according to a deposition by Eileen Sullivan, the Department of Public Health’s chief operating officer.

Months later, the state allowed Steward to open the heart center.

In a recent interview, Allwes, now head of a national health care company, affirmed the picture she painted in her deposition. “There was a general reluctance to hold Steward accountable and always an eagerness to make sure things were beneficial to them,” she said.

Bharel did not respond to requests for comment.

Former Public Health commissioner Dr. Monica Bharel stood for a portrait in downtown Boston in 2020. A former health department official said Bharel ordered her to remove from a public presentation data that portrayed Steward in “a negative light.” Bharel didn't respond to requests for comment. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

Laws flouted without consequence

On paper, Massachusetts boasts some of the nation’s strongest regulations for protecting public health when hospital systems seek to close or discontinue essential services. The regulations require operators to notify the Department of Public Health at least 90 days before the closure to prevent patients from being cut off from critical services.

Over the past decade, state health officials have allowed Steward to flout these regulations without any apparent disciplinary action.

A Spotlight review found at least eight instances in which Steward closed hospitals and critical-care units without proper notice — sometimes without even informing state regulators at all. In at least four other instances, Steward broke contracts with the state by closing hospitals or units they had specifically promised to keep open.

In April 2020, at the height of the pandemic, nurses at Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer and Holy Family Hospital in Haverhill discovered the doors to their intensive care units had been shut — without any notice to state or local authorities. Days later, ventilators and other equipment were carted out of the hospitals, according to the Massachusetts Nurses Association.

Yet when the union called on the state health department to inspect the shuttered ICUs, the agency responded in an email that Steward had assured them the units were open, according to documents shared with the Globe by the nurses union.

Frustrated nurses ventured inside the ICU unit at Ayer to take videos of the vacant rooms, unused medical equipment covered with sheets, and empty patient logs — and sent them to the Executive Office of Health and Human Services as evidence.

The state health department then sent in inspectors to confirm what was long evident: that the ICU was empty and sick patients were being boarded in the hospital emergency department. Even so, then-Secretary of Health and Human Services Marylou Sudders, a Baker appointee, took no immediate action, and the critical ICU beds reopened 45 days later only after legislators raised alarms. Sudders declined to comment.

The hallway inside the emergency department at Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer, on the last full day of operations before it closed its doors on Aug. 31. (David L. Ryan/Globe Staff)

Soon, another crisis hit.

On May 11, 2020, poor maintenance and a wandering mouse triggered a power outage at St. Elizabeth’s and heart monitoring equipment and other devices stopped working, the nurses union said. Nurses had to use smartphone flashlights to rush patients out of darkened rooms and into an ICU packed with COVID-19 patients.

Again, the state was alerted and failed to act.

Leaders of the nurses union told state health officials of “horrifying conditions” and possible fatalities, emails and letters show. More than 24 hours later, a state official called the union and said no action was needed because “Steward says all the lights are on,” according to Dana Simon, director of strategic campaigns at the nurses union. Eventually, the nurses turned to the city of Boston, which dispatched a team of inspectors who helped restore the power.

“I am shocked that no one died,” Ellen MacInnis, a nurse there during the 38-hour outage, told the Globe. “The state just blew us off like we were crazy.”

Over the next few years, Steward would close units in at least four other hospitals without giving proper notice and holding public hearings as required.

“If it’s an essential service, then you can’t just look the other way — but that’s what the state does, time and again,” said Hattis of the Lown Institute. “Why even have these laws if they aren’t enforced?”

Through a spokesman, Baker, who was governor for much of Steward’s downward spiral, released a statement disputing that the state went easy on the hospital chain. Rather, his administration had, during the time of COVID-19 recovery, “restricted access to distressed hospital payments” because of Steward’s non-compliance with state reporting requirements.

Throughout the pandemic, the spokesman added, Massachusetts and many other states loosened regulations on an emergency basis to help providers maintain operations.

“Many of the events the Boston Globe raises here fell within this period of unprecedented strain on the entire Massachusetts health care system,” the statement read. “Governor Baker is outraged by the behavior of de la Torre and the senior leadership team at Steward as they apparently put their own personal gains ahead of their patients’ and workers’ wellbeing.”

‘Credit to the boss’

Steward’s executives were not shy about trying to stay in the good graces of elected officials.

As the company expanded, its leaders gave generously to federal and state candidates in regions where Steward did business, according to a Globe review of campaign finance databases. Those executives’ donations spanned states from Massachusetts to Texas and totaled millions of dollars.

Steward aggressively pushed its employees to donate.

At headquarters, handwritten notes were placed on desks requesting donations — often for specific dollar amounts — for Healey, Coakley, Baker, and others, former employees told the Globe. The company’s lobbyists would also routinely email people about which of the various House and Senate races around the country to give to, sometimes with barely a day’s notice, according to emails obtained by global journalism outlet the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project and shared with the Globe.

Eleanor Gavazzi (left, waving flag) shouted at a rally advocating to keep Steward's Carney Hospital and Nashoba Valley Medical Center open. The rally took place on the front steps of the State House in Boston on Aug. 28. (Andrew Burke-Stevenson for The Boston Globe)

In those emails, Steward lobbyists and lawyers urged recipients to donate the maximum possible — and even use their spouses’ names to double personal contribution limits — so the company could raise funds “that we will credit to the boss.”

“It is vital that you go on line and make your donations by tomorrow,” one email read.

Though emails said the requests were voluntary — mandating donations is illegal — former employees said they felt pressured to give.

A former top administrator in Steward’s corporate suite recalled being asked by company executives to write $200 and $500 checks to Healey, Coakley, and a half-dozen other state politicians. He was told to hand the checks over to a Steward lobbyist, who would “bundle” them with checks from other employees.

“I gave more than I ever would have given on my own — out of fear,” said the administrator, who asked not to be named due to fear of retribution. The Globe confirmed through state campaign finance records that these donations were made.

As the Steward hospital chain rapidly expanded, company executives and their spouses donated substantially to politicians

See aggregate donations to politicians and PACs from 24 Steward executives, plus their spouses, by year.

- Total donation amount

In Massachusetts, the company focused on the state’s gubernatorial and attorney general races. De la Torre had, early in his career, hosted lavish fund-raisers for candidates including former attorney general Coakley. He once held a fund-raiser featuring then-President Barack Obama. (The Obama fund-raiser in 2010 — which snarled traffic for blocks in de la Torre’s West Newton neighborhood — netted Democratic campaigns nearly a million dollars, according to reports at the time.)

Healey was among those who reaped the benefits of Steward’s giving: She raised more than $63,200 just from a handful of Steward executives, board members, and their spouses over the last decade. Baker raised at least $28,400 from the same group.

In Healey’s statewide runs for attorney general and governor, Steward ranked in the top 20 employer groups donating to her campaigns.

De la Torre made sure the politicians knew who was putting up the money. In August 2022, Steward lobbyist Jason Zanetti wrote in an email to company executive Armin Ernst that “Ralph has agreed to help Maura’s campaign with some fundraising.” Zanetti requested Ernst donate $1,000 — the maximum amount under state law — and use a dedicated link so de la Torre would get credit. Less than 24 hours later, Ernst responded: “Done.”

A ‘massive missed opportunity’

With support from state regulators, Steward executives fulfilled their ambitious expansion plans by around 2019. Here again, health officials failed to ensure Steward followed the law.

Six current or former Department of Public Health officials, in interviews, described the state process for approving hospital expansion plans as toothless.

In some cases, they told the Globe, staffers charged with reviewing Steward’s proposals simply cut and pasted language from the proposals because they lacked the staff and accounting skills to scrutinize the assertions.

“The sad part is that the [permitting] process had the potential to hold bad actors accountable,” said a former state official who oversaw hospital expansion plans and who asked to remain anonymous because she continues to work with state agencies. “With Steward, it was a massive missed opportunity.”

For the past decade, Steward has been the only hospital system in the Commonwealth to refuse to comply with a law requiring that audited financial statements be filed annually with the state. The company stopped filing its full financial statements in 2014. The reports are designed to help regulators track spending trends and detect signs of financial stress.

Steward’s failure to file the statements was no secret — and was seen by many as a red flag.

Had regulators kept tabs on Steward’s finances, they would have seen that Steward’s expansion was funded by massive amounts of debt, and that it was on the hook for billions of dollars in future rent payments to its landlord. Regulators could have intervened to prevent, or at least limit, the devastating toll caused by Steward’s collapse, health regulatory experts told the Globe.

In 2016, state health officials developed a new, stronger law — dubbed by some the “Steward provision” — that strengthened the health department’s authority to deny hospitals’ applications for new services if they were not complying with state law.

“We crafted the ‘Steward provision’ so that they can’t get all the things they want to make money until they give you this data,” according to a former state official involved in the process who asked his name not be used for fear of retribution.

The new rule was promptly ignored. The audited financial statements still have not been filed.

Nevertheless, in reports approving Steward projects, health department officials continued to assert that Steward was in “good standing” with federal and state laws and regulations. Had the rule been enforced, regulators might have slowed Steward’s expansion, according to several former Department of Public Health officials.

Advertisement

Distress signals overlooked

By the summer of 2021, anyone with internet access could have uncovered evidence of Steward’s crumbling balance sheet. That’s because its publicly traded landlord, Medical Properties Trust, was required to disclose Steward’s audited financial results to securities regulators. The results were alarming: Steward reported an operating loss of $439 million and a negative net worth of $1.5 billion as of 2020.

In interviews, top state health officials acknowledged they were aware that Steward was in deep financial distress nearly a full year before the company filed for bankruptcy.

By April 2023, the Health Policy Commission, a state agency that oversees health costs, had seen enough signs of trouble to begin playing out adverse scenarios, said David Seltz, the commission’s executive director.

“There was a growing sense of concern and alarm with each month that passed,” Seltz said.

Steward sent multiple distress signals to state health regulators as well.

In the fall and winter of 2023, several Steward executives made regular trips to Beacon Hill to seek emergency financial help. In September, the executives sought and received a $12.65 million infusion of cash — an advance on anticipated Medicaid payments — from Healey’s administration.

By January, de la Torre and Steward executive vice president Dr. Michael Callum delivered to Walsh a grim prognosis: Steward’s losses were unsustainable and the company would have to transition its hospitals to new owners.

Good Samaritan Medical Center, a former Steward hospital, is now operated by Boston Medical Center. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

Fired nurse had political connections

The Healey administration intervention on behalf of Holly Zachos, the nurse at Good Samaritan, in September 2023, came as the meetings with Steward executives were underway.

Zachos had connections to Healey that stretched back a decade: Her husband, attorney George Zachos, was chief of the state’s Medicaid fraud division under Healey. Healey publicly lauded his “strong leadership and expertise” in “protecting the integrity of our health care system.”

He left the attorney general’s office in 2016 to become the executive director of the state’s powerful doctor licensing board, but continued to support Healey’s political career, donating to her run for governor in 2022.

Word of Healey’s intervention quickly spread through Good Samaritan’s emergency department. Several nurses said they were surprised to see Zachos back on staff, especially after state and federal health investigators cited Zachos’s actions in an investigation into Knight’s death. (The union lost its challenge to the company’s forced retraining of Zachos.)

“This basically sends a message that you can throw the nursing standard of care in Massachusetts out the window,” said Jodi Moen, a veteran emergency department nurse at Good Samaritan, who described the intervention as “appalling.”

Healey herself spoke with Holly Zachos in March 2023 when the governor, along with Walsh, took a tour of Good Samaritan, according to Pinkham, of the nurses union. During that visit, Zachos spoke with both officials in the hospital’s chapel about the dangerous conditions within the hospital, a move that, union officials allege, put her at risk with Steward executives.

“She was very worried, and expressed this to me frequently, that she’s got a huge target on her back,” said Simon, the director of strategic campaigns at the nurses union.

It’s unclear whether Steward executives were made aware of the conversation with the governor. Zachos’s termination letter made no mention of anything beyond her failure to “follow nursing standards of care” in relation to Jennifer Knight’s September 2023 death.

In the four years before Knight’s death, the Massachusetts Nurses Association repeatedly warned state officials about deteriorating conditions and understaffing at Good Samaritan. In letters and phone calls, nurses described patients dying unmonitored on hallway stretchers because they had nowhere else to put them. Often staff lacked enough portable heart monitors and electrical outlets for people queued up in the corridors. On some nights more than 80 people packed the emergency department, with the registration line stretching to the sidewalk, several emergency department nurses told the Globe.

The perilous conditions reached a critical point in the summer of 2023.

Severely ill patients who required care within minutes were left unwatched in the waiting room for hours, according to a federal investigative report. In one instance, a nurse left a vomiting patient in the waiting room for 11 hours. A friend discovered the patient barely conscious. Inspectors were critical of the hospital’s response, which consisted of sending an email to nurses, “reeducating” them on procedures. The inspectors noted that the hospital didn’t track who opened or read the email.

Two days after Knight’s death, Zachos filed an “unsafe staffing form” with the hospital that noted the emergency department that night was at more than double its capacity. There were 90 patients, with waits so long that many patients left without being diagnosed. Twenty-three nurses should have been on duty, her report said. There were only eight.

Margaret White, an emergency department nurse at Good Samaritan, said she still has recurring nightmares of patients screaming out for help from hallway stretchers — and being unable to reach them in time. Almost every shift for a year, until early 2023, White said she called a 24-hour Department of Public Health complaint line to report unsafe conditions — but eventually gave up due to a lack of response.

“We all felt hopeless,” said White, who is on a leave of absence after she was assaulted by a patient. “There were times I would run into that [hospital] chapel and pray, ‘God, please sustain us for the next four hours.’”

Conditions at the Good Samaritan emergency department did not improve until after the state sent in monitors to Steward hospitals on Jan. 31 of this year, after the Globe reported on the death of a pregnant woman at another Steward hospital and the financial crisis engulfing Steward finally became public.

‘They should be held accountable’

Donna and Joseph Knight displayed a photograph of their daughter, Jennifer Knight, on a dresser at their home in Middleborough. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

A year after their daughter’s death, Donna and Joseph Knight struggle with unanswered questions. How could someone complaining of chest pain collapse and die just feet from nurses trained to provide life-saving care? Why was she not admitted earlier? Would it have made a difference?

An autopsy later showed she had a severe blockage in one of her arteries.

When the couple arrived at the emergency department that September night, they were left alone for what felt like hours in a conference room.

Not then or after, did the hospital inform them of the events surrounding her death. Until reached by a Globe reporter, the Knights didn’t know about Zachos’s firing — or her rehiring. Nor were they told that state and federal regulators had faulted the nurse in the care of their daughter.

In his eulogy at Jennifer’s funeral, Joe Knight, a retired State Police sergeant, recounted his daughter’s lifelong love for the Boston Bruins and her devotion to her mother. Among the more than 200 attendees was a large contingent from Alloy Wheel Repair Specialists in Randolph, where Jennifer Knight was a popular office manager.

The failure of the state to act forcefully baffles her mother.

“I just don’t understand,” Donna Knight told the Globe. “They should be held accountable.”

Jessica Bartlett and Hanna Krueger of the Globe Staff contributed to this report. Khadija Sharife of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project also contributed.

Chris Serres can be reached at [email protected]. Liz Kowalczyk can be reached at [email protected]. Elizabeth Koh can be reached at [email protected]. Spotlight editor Brendan McCarthy can be reached at [email protected].

Feedback and tips can also be sent to the Boston Globe Spotlight Team at [email protected], or by calling (617) 929-7483. Mail can be sent to Spotlight Team, the Boston Globe, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

Donna and Joseph Knight held the urn of their daughter, Jennifer, at their home in Middleborough. Many circumstances of her death last year were unknown to them until recently. (Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff)

Credits

- Reporters: Chris Serres, Liz Kowalczyk, Elizabeth Koh, and Brendan McCarthy

- Contributors: Jessica Bartlett and Hanna Krueger

- Editors: Brendan McCarthy, Gordon Russell, and Mark Morrow

- Visual editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photos: Craig Walker, John Tlumacki, Jessica Rinaldi, Joanne Rathe Strohmeyer, Erin Clark, David L. Ryan, and Suzanne Kreiter

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Kevin Martin

- Data editor: Yoohyun Jung

- Design: Ashley Borg and John Hancock

- Development and graphics: John Hancock

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC