Boston Globe Spotlight Team

Boston Globe Spotlight Team

A broken bond, a shaken citadel of science

Kristin Knouse and David Sabatini, both biologists, had an intimate relationship that bridged boundaries — she is young in her career, he is globally renowned — and broke the rules at Cambridge’s Whitehead Institute. After Knouse alleged harassment and other complaints emerged, an investigation rocked Whitehead, forced out Sabatini and damaged all involved. Did it have to end this way?

The two women from Whitehead Institute sat at a quiet table outside Tatte Bakery & Cafe in Kendall Square on Oct. 19, 2020, trying hard to extend their small talk before the conversation turned serious.

Ruth Lehmann, who had started as Whitehead’s director only a few months earlier, had brought along her Australian shepherd, who lazed on the sidewalk. Sitting with her was Kristin Knouse, one of the institute’s young, talented researchers who, during this conversation, could barely suppress her nerves. Her future was at stake — and maybe that of others.

Lehmann had set up this meeting to resolve a mystery: Why was Knouse, then 32, leaving Whitehead prematurely, midway through her prestigious five-year fellowship? It was a stunning step; it made no sense.

Lehmann, an award-winning germ cell biologist, had built a career in a male-dominated field and championed the success of young scientists like Knouse. On her first day as Whitehead director that July, she had promised to foster “a culture of excellence” and about a week later, commissioned a firm to conduct a diversity, equity, and inclusion survey of all staff. She couldn’t know it at the time, but the survey would, in tandem with other concerns voiced by staff, have seismic consequences.

She was aiming to improve the work environment of the place, and facing sobering realities.

The National Institutes of Health, a major government source of grants for Whitehead, had threatened fiscal penalties for institutions that didn’t transparently, and vigorously, address issues of sexual harassment and misconduct. This came after a 2018 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine found pervasive discrimination against women in science. Since the report, institutions nationwide had begun removing the names of over 100 scientists accused of sexual harassment and other misconduct from grants and awards funded by NIH.

“I hope that we can undertake honest, productive, and difficult conversations together,’’ said Lehmann, then 65, in an email to all employees on her first day as the head of Whitehead.

Lehmann knew that cultural change would come hard, because it meant dealing with issues endemic to the large, modern science labs that have turbo-charged this region’s economy. For decades, some researchers have complained that the labs often become imperious environments driven by the personality and priorities of the lab leader — the so-called principal investigator or P.I. Young scientists can become dependent on these research stars for career advancement and often feel they have little recourse if they have complaints.

That day at Tatte, Knouse couldn’t bring herself to unload her own complaint, couldn’t tell Lehmann that her anguish was all about one of those scientific stars — David Sabatini — and how, over time, her view of their complicated relationship had changed. She had come to see him as the source of her despair.

Advertisement

As far as the outside world could see, she and Sabatini were colleagues and friends, but the truth was that, off and on for more than a year, they had had about a dozen secret sexual liaisons — secret because, beyond wanting to avoid eyebrow-raising gossip, they knew that such relationships between scientists in their positions were strictly forbidden at the Whitehead. The two had bonded at first over their shared love of science — he had been her teacher and mentor — and good whiskey. And then, in an arrangement that she later told confidantes caused her increasing unease, they had casual and clandestine sex.

All along, they had agreed their relationship wasn’t exclusive, that they could see others. And he had, taking up with an American scientist based in Germany who had briefly worked in his lab. When he told Knouse about it in early 2020, she spoke of hurt and ended the relationship.

Her emotions evolved to something else. It was not about jealousy or disappointed hopes, according to friends who spoke to her then. Over time, she had become hardened in her view that Sabatini had exploited her, and that, she believed, he had a pattern of pursuing other young female scientists who craved his professional blessing.

For this reason, she sought to leave Whitehead. She also wanted to expose the powerful scientist she believed might hurt other vulnerable women.

Sabatini has said to the Globe that he never exploited his power in any way with Knouse, or any other woman.

In the meeting with Lehmann that day, Knouse found it hard to contemplate, much less talk about something so painful, so confusing, and so long a secret. She was frightened, as she told trusted colleagues, of the likely backlash.

And so when Lehmann asked why she was leaving, the younger scientist said only that she had experienced “harassment” that had deeply affected her mental health. She didn’t say what kind of harassment, or by whom.

Knouse’s allegation, though initially vague, landed like a ticking time bomb in Lehmann’s lap. After decades immersed in laboratory life, she knew that sexual harassment against women in science was all too common and that any probe would inevitably convulse the workplace, unleashing forces that could blow up into lawsuits, disruption, and truth-twisting social media storms. Lehmann had only met Knouse once before, briefly, at a work retreat.

By the next month, November, Lehmann appeared to know much more. She seemed to have some idea that Knouse intended to make a complaint about Sabatini, according to e-mails between Knouse and Lehmann reviewed by the Globe. Soon, more of Knouse’s account, full of nuance and complications and assertions that Sabatini furiously disputes, would emerge.

A sisterhood

There were good reasons why it seemed unthinkable for Knouse to leave Whitehead, and to name Sabatini as the root of her growing pain.

The institute is one of the world’s leading centers for biomedical research, a powerful draw for the best minds in the field, the capstone for a career. Very few young, aspiring scientific superstars — and Knouse was surely one — would walk away from such an opportunity.

For Knouse, even though her lab was still small, getting to a place like Whitehead and working with internationally renowned researchers had been the fulfillment of a long-held dream, though she wasn’t one of those precocious souls who had known since childhood that science was the center of their world. Growing up in Allentown, Pa., she told the Globe, she didn’t have many strong female professional role models; her mother was largely a stay-at-home mom raising her and her two younger siblings. She had imagined she might be a medical doctor, like her father.

But a summer high school science enrichment program lit the spark, and her undergraduate studies at Duke and graduate work at the Harvard/MIT MD-PhD program only confirmed her love of biological research — and her uncommon gift for the work. She became fascinated by the liver’s capacity to regenerate after injury, and wondered whether unpacking that mystery could help in the treatment of other organs.

“There was a fire inside me for this,’’ Knouse told the Globe, in her first of two interviews since her role in the Sabatini controversy became public. (Knouse declined several previous requests for interviews, but ultimately consented on the condition that her lawyers be present and that she would not publicly discuss her relationship with Sabatini due to his pending defamation case against her.)

Taking on Sabatini was hard for her. Beyond the fact of their sexual entanglement, he had been at times a special mentor to her, and having an influential patron is critical to success in the rarefied upper echelons of science. She also knew he would insist — and he did — that their sexual relationship was entirely consensual, and that his past record shows deep respect and support for female scientists. She worried about whether she could prosper at Whitehead or anywhere, if she angered Sabatini and he turned on her.

“If I launch an investigation and he DOESN’T get fired, my life will be hell,” she said to a lab member in a text obtained by the Globe.

Knouse’s resentment of Sabatini intensified when she summoned the nerve, sometime in 2019, to open up about her feelings to a handful of other women at Whitehead. They were part of an informal sisterhood that had evolved within this 40-year-old biomedical research institute, and they often traded exasperated text messages at all hours. They also confided in one another outside the lab, while jogging or kayaking or sipping cocktails.

These women were mostly young, from diverse backgrounds, and in the early stages of their careers. Their presence at Whitehead highlighted some recent successes in diversity and inclusion efforts at the institute. Women now represent about half of the total employee pool at Whitehead, though they make up only a quarter of its principal investigators and fellows.

When some of the women got together socially, all kinds of subjects were on the table, including their uncomfortable experiences involving Sabatini and the offensive edge of some of the discourse in his lab, according to interviews and texts reviewed by the Globe. There was talk of advice they had received from other researchers to “play hard to get” with him to get his support and about his eye for attractive women in the lab.

Note: Text exchanges between individuals in this story are animated.

In the fall of 2020, Knouse and other women took part in Whitehead’s zoom viewing of a newly released documentary, “Picture a Scientist.” It was about the decades-long struggle by women in science for equity and respect, and featured retired MIT molecular biologist Nancy Hopkins, as well as a former BU graduate student, Jane Willenbring, whose sexual harassment allegations against geologist David Marchant led to his firing in 2019.

After the viewing, Knouse thought to herself, as she recalled to the Globe, “It is wrong for me to stay quiet.”

She mulled her next steps methodically and anticipated how she would likely be portrayed.

Knouse’s texts that were shared with friends and investigators — and reviewed by the Globe — appear to document a gradual and wrenching evolution of her emotional state. Her feelings of exploitation had run alongside a wish for a more meaningful relationship with Sabatini, but then, at some point, Knouse became openly hostile, and wanted Sabatini to be held accountable.

The texts are not as revealing about when her change of mind began or exactly what triggered it. Sabatini and Knouse offer sharply different accounts on this score — she saying her sense of exploitation, there from the start, only escalated over time; he saying the shift came only after she learned of his new relationship. But the texts do suggest how deeply wounded and angry Knouse had become.

The texts show that Knouse, in the months before her meeting at Tatte with Lehmann, had brainstormed with friends about how she could confront Sabatini and see him penalized.

This was all happening at a time when Knouse was losing the support and counsel of one of the strongest female scientists she knew — Angelika Amon, an MIT professor who had been her mentor since graduate school. Amon was diagnosed with terminal ovarian cancer in 2018 and died on Oct. 29, 2020.

“She believed in me before I believed in myself,” Knouse told the Globe.

Amon’s widower, Johannes Weis, said in an interview that when Knouse confided in Amon about her sexual liaisons with Sabatini, his wife was angry and upset with Sabatini, whom she had long viewed as a trusted MIT colleague.

“It was abundantly clear to me that Angelika thought that this was inappropriate,’’ Weis said, “and it was David’s job not to let it happen.”

As she battled cancer, Amon tried to protect Knouse, one of her top graduate students, recommending that she not file a complaint in the Whitehead system while she still worked there.

“She was very worried about Kristin,’’ Weis said. “She offered guidance. But ultimately she knew it would have to be Kristin’s decision.”

Knouse, as she planned next steps, had sought advice from MIT’s Ombuds office, a source of confidential counsel for MIT faculty, students, and staff, at least one Title IX lawyer, and another senior MIT professor about how she might proceed against Sabatini, according to texts and interviews.

Knouse had received advice that, to make a strong case against Sabatini, it would help to show a pattern of inappropriate behavior. Knouse began encouraging researchers she knew who had privately complained about Sabatini to speak to Whitehead authorities; some agreed and some declined.

The senior MIT professor, who knew the risks faced by women who take on powerful scientists, also later gave Knouse the name of a legal expert who could help in any protracted legal fight: former federal judge Nancy Gertner.

As Knouse texted to a friend: “hopefully in a few years time i can look back and be like damn i fixed a huge systemic problem.’’

On Dec. 10, 2020, Whitehead’s diversity, equity, and inclusion survey, the culture-challenging initiative launched by Lehmann, dropped in Knouse’s e-mail box, as it did for more than 500 other employees at Whitehead. It offered a confidential way for Knouse and others to voice their concerns.

It would be the beginning of Sabatini’s undoing.

A career on the rise, then trouble

David Sabatini was riding high at the start of 2020.

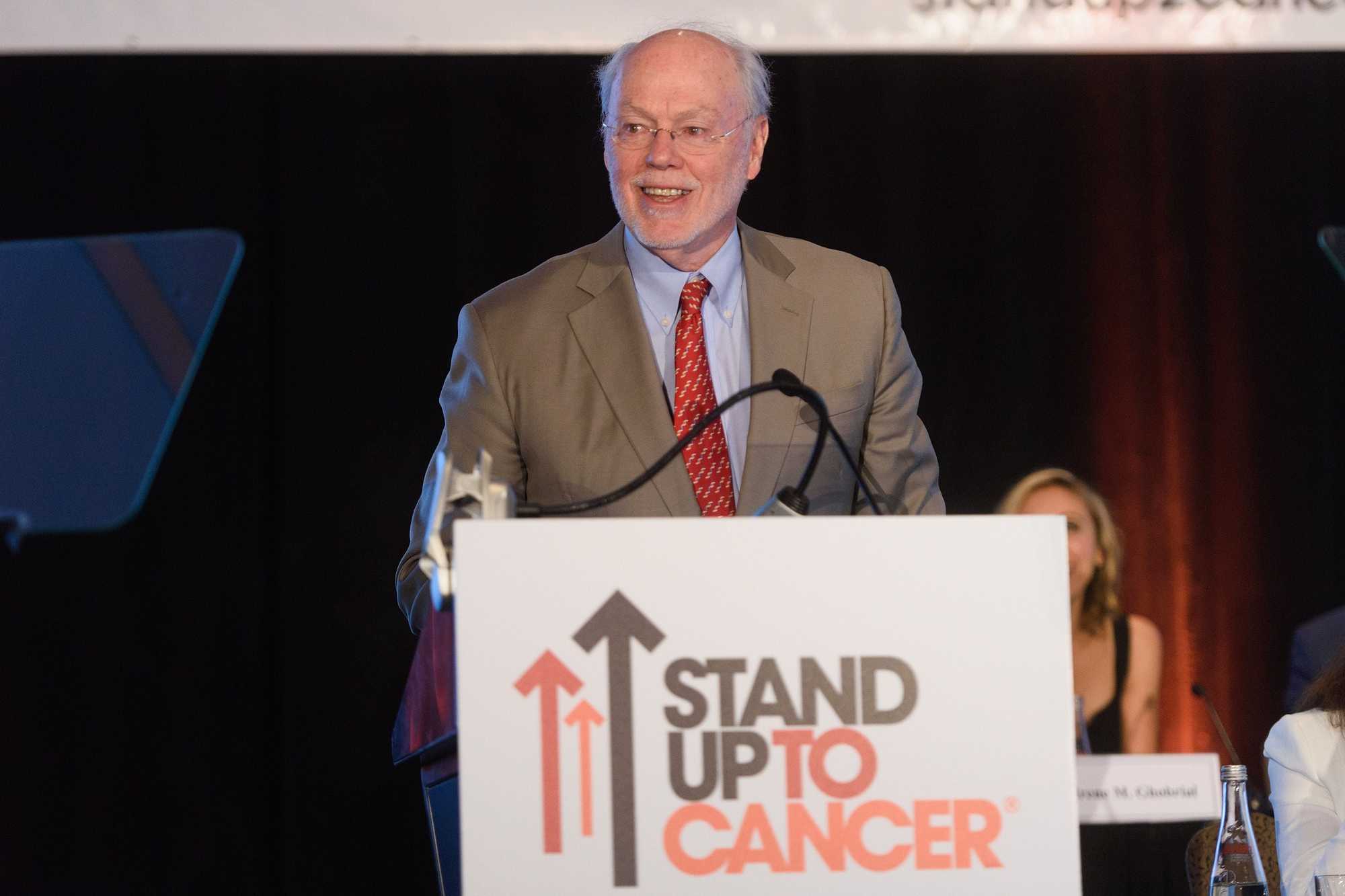

Awards and money were pouring in. He received Columbia University’s Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize, often considered a precursor to the Nobel Prize because many recipients have gone on to win one. He also shared the Sjöberg Prize for significant contributions to cancer research.

Sabatini’s achievements and growing renown also made him a magnet for researchers, many of whom were attracted by his high-intensity lab. They published scientific papers at a prolific pace, more than 200 since he launched his lab in 1997.

“There was a great esprit de corps in the lab,” said one member who was there in the years leading up to Sabatini’s fall. “It was great to be around that energy.”

Sabatini’s personal life was also taking off as well — and he married for the second time.

He had fallen in love with Lena Pernas, the researcher based in Germany who had briefly worked in his lab. Sabatini told some in his lab that the two had a “crazy connection.” He made plans to visit her overseas.

In the last days of 2020, Pernas traveled to Cambridge. On Dec. 29, she and Sabatini appeared in the Cambridge city clerk’s office and married.

Pernas did not respond to a Globe request for comment.

But amid these moments of happiness, ominous clouds were building around Sabatini’s lab. By early 2021, as the diversity, equity, and inclusion survey and a pair of other complaints came into HR around the same time, Lehmann and other administrators began to suspect one of Whitehead’s top labs may have a toxic underside.

It was abundantly clear to me that Angelika thought that this was inappropriate, and it was David’s job not to let it happen.”Johannes Weis, Angelika Amon's widower

The first signs of trouble became clear when Jones Diversity, the firm hired by Whitehead to direct the survey, began to tally the input of 225 staffers who anonymously completed it — representing roughly 40 percent of the workforce. While most addressed Whitehead’s work culture generally, three anonymous respondents singled out Sabatini.

Among them was a “white male graduate student” who said that Sabatini tolerated a particular visiting scientist who routinely made sexist and racist remarks. Another of the complainants was Knouse, the Globe has confirmed, and the third was a female trainee who did not work in Sabatini’s lab.

Separate from the survey, two female researchers who trained with Sabatini spoke to the human resource department in January 2021, according to the Whitehead investigative report, which kept their names anonymous. One of the women, a former postdoc, told Whitehead officials that she was not treated as a scientist, but as a “female scientist.” She felt she was seen as a “potential person to date” in Sabatini’s lab. She said that Sabatini, at a work retreat, asked her to “pick” between two male postdocs and was once asked by him whether she was romantically interested in his brother, Bernardo, a Harvard neuroscience professor.

The other was a former MIT graduate student who reported a “culture of competition” in the lab, but for the wrong reasons, the investigative report said. She told human resource officials that Sabatini showed more personal attention to “attractive” lab members and that female trainees deliberately “flirt a little” with Sabatini because they believe it will boost their careers.

Several other women in the Sabatini lab at the time, however, told the Globe that Sabatini never fostered a sexualized environment. “It’s unequivocally not true,” said one woman from the lab.

But the complaints of the two scientists to Whitehead human resources — both well-respected and more senior than Knouse — carried credibility with administrators and had legal impact. Lehmann, now faced with credible sexual harassment complaints against a named individual and the DEI survey results, was legally compelled to investigate.

Meanwhile, Jones Diversity reported its survey’s findings to Whitehead leadership. It scheduled a Zoom presentation for principal investigators and fellows to explain the results on March 25, 2021.

An investigation begins

Both Sabatini and Knouse were among those on the Zoom screen, looking at slides displaying statistics and quotes.

The overall DEI results found that the “culture within the Whitehead community is not inclusive for all. Women and people of color feel significantly less included than white males.”

The survey, focus groups, and interviews also documented that “the laboratory environment” was a particular area of concern. More than 30 percent said they heard “offensive language,” about topics such as race, LGBTQ status, and gender, among others. The primary source of offensive language was the institute’s most powerful players, its principal investigators, the survey said.

Whitehead DEI survey results

31%

Percentage of survey respondents who said, in the past three years, they have heard someone at work make offensive comments involving issues such as race, age,weight, LGBTQ status and gender.

28%

Percentage of people of color who felt they “need to hide a part of their identity” to assimilate at Whitehead, about twice that of white respondents.

54%

Percentage of administrative and support staff who said they felt comfortable reporting offensive comments to leadership, but only 11 percent of scientific researchers felt the same, suggesting a more tenuous connection to the institution.

Sabatini attended the Zoom from Germany, where his new wife lived. He told the Globe he had no idea any of the survey complaints were focused on him.

Later that day, Knouse reiterated her resolve to take action against Sabatini after attending that meeting.

She texted to her friend, “i am out for blood at this point,” then later added, “i’m so ready to get this over with.”

Sabatini was asked to attend another Zoom meeting the next morning, with Whitehead board members Susan Hockfield, a former MIT president, and Phillip Sharp, an MIT biology professor and a 1993 Nobel Prize winner.

They informed him that several respondents in the survey had singled out his lab. They said Whitehead would launch an investigation into him and his lab.

Sabatini replied that he always offered help to people who felt aggrieved and denied ever threatening to retaliate against them, according to Whitehead notes from the meeting. He said he had a strong record of supporting women.

He was shocked by what he heard, Sabatini told the Globe. He was hearing about some of the complaints for the first time and had never imagined that some of the banter in the lab would lead to a large-scale investigation.

Hockfield and Sharp did not respond to requests for comment.

Meanwhile, Lehmann, early in her tenure at Whitehead, was facing a nightmarish personnel crisis around one of the institute’s most prominent scientists who brought in massive research dollars.

She wrote to Sabatini outlining the concerns raised by “the survey and other sources.” She said outside investigators would seek to interview members of his lab or others who may have helpful information.

And, in what would prove to be a test of whether she could trust him, she explicitly ordered him not to try to interfere with the investigation in any way.

“We strongly advise you to refrain from asking anyone in your lab whether they have met with the investigator, plan to do so or the content of what they communicated,’’ Lehmann wrote. “Failure to abide by these strong recommendations will be considered a serious breach of trust.”

About six weeks later, an official from one of Sabatini’s principal funders, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, notified Sabatini they had been informed that the Whitehead probe also included sexual misconduct and harassment allegations.

The complaints of Knouse — and others — had been heard.

The escalation

Many powerful figures in Sabatini’s situation might have responded to such a potentially career-destroying crisis with contrition and humility. And some institutions, faced with accusations about an accomplished longtime employee, might have sought or negotiated a compromise disciplinary path.

In this case, neither Sabatini nor Whitehead opted for moderation.

Sabatini told the Globe that his lab had developed a vibrant culture and that he felt no need for apologies.

Lehmann would not comment on whether Whitehead leadership had considered a less confrontational legal option — anything short of a full investigation by a law firm.

The probe stretched over five months. The law firm hired by Whitehead, Hinckley Allen, assigned three lawyers to investigate the culture of the lab and Sabatini’s leadership. The lawyers interviewed more than 40 people and collected more than one million records, including e-mails, texts, and Slack messages, pulled from Whitehead’s IT system.

Sabatini said his sense of alarm began to grow about a week after the probe began. Though Lehmann had told him not to speak to lab members about the investigation, he did have conversations with some employees and learned that lawyers had asked tough questions that seemed aimed at him.

Sabatini also had to know that something he had kept secret — the fact of his past sexual relationship with Knouse — could blow up at any time with potentially damaging consequences. Such a relationship was strictly barred under Whitehead policies, and of course he knew that, too.

That Knouse might reveal the secret could not have surprised Sabatini. The space between Knouse and Sabatini had grown hostile since the investigation began, as she had virtually stopped talking to him and moved her lab office — previously next to Sabatini’s — to a different floor.

But if there was any doubt in his mind, it likely evaporated shortly after the probe began. Two of the top litigators in the city, Gertner, the former federal judge, and Ellen Zucker, a high-powered lawyer who handles many employment cases, notified Sabatini that they had been retained by Knouse and may be filing a potential harassment and retaliation case after the Whitehead investigation was over.

With the lawyers on board, Whitehead and MIT were also put on notice; the stakes had been exponentially raised.

But even then, Sabatini said, he did not see this for the existential threat it was. He said he banked on his own sense of what was true — and on his trust in his colleagues to put the complaints in proper perspective.

“I had a feeling that, OK, this is my home,’’ he said, of Whitehead, during a Globe interview. “I’ve been here forever. I’ve done lots of good and this will be fine.”

He said he asked to speak to Lehmann as the investigation began, but Lehmann declined, saying she wanted to let the investigation play out.

Sabatini soon hired Cambridge lawyer Todd Bennett to advise him.

Advertisement

Morale inside the lab plummeted. A number of former lab members who were questioned in the investigation told the Globe that they left their interviews shellshocked by the aggressive tone of the questions they were asked.

“It felt like the lawyers came with a thesis already made,” said one former lab member.

A Whitehead staff member said several Sabatini lab members confided in him, saying they felt “they would be personally in trouble if they didn’t give the answer these lawyers were looking for.”

“A couple of people said they wrote to Ruth [Lehmann] to say it was a manipulated process, and they felt harmed by it,” he said.

Lehmann acknowledged that some lab members raised concerns about the Hinckley investigation, and she was later assured, after speaking to the investigators, that they were making every effort to “minimize stress” in the lab.

Investigators interviewed Sabatini three times, Knouse twice. In the first of those sessions, she revealed her sexual interactions with Sabatini; it was the first time investigators said they learned of the liaisons. When they later questioned Sabatini about this revelation, he then admitted that he took part in it and depicted it as a consensual relationship between colleagues.

Meanwhile, even though ordered by Lehmann not to interfere with the investigation, Sabatini did more than just speak to some lab members. He also acknowledged to the Globe he showed several of them a sample of the texts Knouse had sent him in early 2020 when she wrote of wanting a deeper relationship with him.

Sabatini insisted to the Globe that he did not obstruct the investigation. He said that after hearing comments from members about their interviews with investigators, he had merely asked them whether they thought the probe was really about lab culture. A former member of his lab told the Globe he believed Sabatini had reached out to other lab members out of concern, after being told that some were “freaking out.”

The investigators submitted the report to Whitehead executives on Friday, Aug. 13, 2021, and then to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and MIT.

A scathing report

The investigative report resounded like a thunderclap. It stretched over 248 pages and painted a scathing portrait of Sabatini. There were only a limited number of positive references to him, citing his scientific brilliance and leadership of an intense, hard-charging lab bent on breakthrough findings. Investigators noted that the vast majority of lab members did not complain and that negative experiences were confined to a smaller number of lab members, among them “females and diverse members.”

Still, in the main, it was an unrelentingly negative depiction of Sabatini as a man who acted as if the rules didn’t apply to him. It cited Sabatini for enabling — and participating in — a gossip-filled environment with uncomfortable sexual overtones, and included specific examples.

High up in the report, they accused him of obstruction, for engaging with lab members in violation of Lehmann’s directive, and there was also the critical question of Sabatini’s credibility. It is a sphere in which they deemed him wanting. He was depicted in the report as “not credible” during his three interviews, even when presented with texts or other information to contradict his accounts.

For instance, according to investigators, Sabatini allegedly denied making a comment about preferring European women to American women because they talked more freely about sex, but was later presented with e-mails or texts suggesting he had.

Sabatini later would tell the Globe that investigators had asked him about incidents in the past that he simply couldn’t immediately recall.

It was clear that in the credibility contest between Sabatini and Knouse, the investigators overall believed Knouse. They also said they did not think she was motivated as a spurned lover to speak out.

Investigators said they did not find that Knouse had disclosed her sexual relationship with Sabatini to damage his reputation. They said they believed that “she felt trapped and obligated to Sabatini because he was her Fellow mentor and senior scientist.”

Investigators, for example, found credible Knouse’s assertion that it was Sabatini who was the initiator of almost all their proposed or actual sexual encounters. And that she was pressured to have sex with him in the fall of 2018 when she was a fellow on her first Whitehead retreat in New Hampshire. Sabatini admitted they had sex once at that retreat, at least several months after their first encounter, but told investigators that Knouse initiated it, and subsequent texts turned over to investigators represented their efforts to arrange for it. He also said that she never expressed misgivings.

Knouse produced texts showing he requested sex three times beginning before the retreat when he inquired of her, “Maybe a discrete consult in NH?” She also shared a text showing she told him she was reluctant to go along, citing “(a)ggressive policies, pre-existing target on my back, residence at the bottom of the food chain, and rooming with other fellows leaves so little room.”

The investigators reviewed many texts between the two, but not nearly all of them. Sabatini turned over all of his after the end of 2019, that is, after the sexual liaisons were over. He said prior texts were on another phone he no longer has. Knouse turned over a selection of her texts from the whole span of her relationship with Sabatini, focused on those that support her version of events.

Newsletter: The Globe Investigates

Sign up to receive Spotlight reports and special projects in your inbox.

Knouse had also told them of seemingly contradictory emotions about Sabatini, sometimes apparently wanting more from him, other times complaining about being exploited.

She “stated that her comments reflected her mixed and complex feelings for Sabatini at that time. (Knouse) told investigators that part of her wanted to be in a real, not simply sexual relationship with Sabatini, but that ... she knew that the ongoing sexual relationship with Sabatini had been the source of her deep mental health struggles, lack of productivity, and unhappiness.”

The report details the starkly diverging narratives from Knouse and Sabatini about what led them to have sex for the first time April 18, 2018, in Sabatini’s hotel room at Maryland’s Rockville Hotel after a night of drinking and dinner at a restaurant in Washington D.C.

According to Knouse, she was coaxed that night to lie on the bed next to him, even as she told him that this was a bad idea. When she recounted the reasons, including professional ones, she said he got angry and impatient. She said she felt she could not say no to him because of his stature in the field, and potential influence on her career, and eventually yielded to having sex. She said that she continued to acquiesce and have sex with him on other occasions, but that her mind was full of mixed feelings.

According to Sabatini, the entire sexual encounter was mutual from the start, and he had no recollection of her protesting for any reason.

He has told the Globe that he had considered Knouse a good friend. He said he believed that Knouse, a woman in her early 30s who now ran her own lab, would have been comfortable saying no if she didn’t want to have sex with him and that he would have respected that.

The investigators made no findings on whether the relationship was consensual, saying it was not part of their mandate. But the investigators said Sabatini and Knouse both violated Whitehead policies barring all principal investigators from having a romantic or sexual relationship with any Whitehead employee, even of the same high level. They did note that Sabatini was a more significant offender due to the status difference between them. He was a tenured faculty member 20 years her senior who still held some official “mentor” roles in her professional career.

In conclusion, the investigators placed Sabatini at the center of the blame, writing: “These findings, in the aggregate, portray a high-achieving but troubled laboratory led by a brilliant but personally flawed and immature scientist whose management of a diverse, talented and vulnerable workforce is inconsistent, arbitrary and, at times, lacking in professionalism and social awareness.”

A rapid-fire ending

Sabatini received the report on Aug. 19, 2021, about six days after it was first released to Whitehead. Within a day of his receiving it, Sabatini’s career imploded.

He told the Globe that he was stunned by the harsh judgments of the report, believing that after 24 years running one of the top labs at Whitehead, he would be given a chance to defend himself against the report’s conclusions.

He was given opportunities to meet with his superiors, but Sabatini saw them as formalities, not a credible offer to hear his side.

He was out within a day — beyond warp speed in the world of academic discipline.

Hours after receiving the report, Sabatini got an e-mail from Erin O’Shea, president of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, asking him to be part of a meeting the next day, on Aug. 20, at 1 p.m. Lehmann was also scheduled to be part of the same scheduled meeting.

That morning around 10:30, the Whitehead board of directors voted to empower a subcommittee of seven members to rule on Lehmann’s conclusion about what should happen with Sabatini. That panel voted unanimously “to affirm the recommendation of the President to terminate David Sabatini as a Member of the Institute on Aug. 20, 2021 unless her recommendation changes.”

The subcommittee included not just Lehmann, Hockfield, and Sharp, but three prominent members of the business community and MIT economic professor Paul Joskow.

Sabatini told the Globe he learned from his lawyer he was going to be fired at the 1 p.m. meeting. Lehmann, though, told the Globe the purpose of the meeting was “to hear David’s side of the story.” She added, “He could have asked for the opportunity to provide further information.”

But Sabatini did not show up at the meeting. Around 11:50 a.m., he sent separate e-mails to Lehmann and O’Shea, saying he was resigning. Lehmann e-mailed back and accepted his resignation.

But O’Shea rejected his resignation and fired him instead, saying in a letter that it was “for cause” and “due to violations of Whitehead Institute and HHMI policies, practices and principles.”

Meanwhile, officials at MIT informed Sabatini that they had received the Whitehead report and that he was being put on unpaid administrative leave while administrators reviewed next steps, including whether to revoke his tenure.

“The report raises very serious concerns about sexual and workplace harassment,’’ wrote Nergis Mavalvala, MIT’s dean of science, in a letter to the biology faculty.

The news threw the Sabatini lab on the sixth floor of the Whitehead Institute into total chaos, as lab members scrambled to save their research projects and figure out if they had a job anymore.

This place where lab experiments once hummed, where scientists hoped to break new ground and find cures for cancer, diabetes, and Parkinson’s, went quiet.

Lawsuits, but new hopes

Sabatini’s paychecks stopped. His mail slot was stuffed daily with notices from organizations cutting ties with him. He learned that his membership in the National Academy of Sciences was being reviewed in light of the allegations.

Sabatini hired prominent Boston litigator Lisa Arrowood to help set the record straight, at least as he saw it. He felt his only recourse for a fair hearing was in the courts. In October 2021, Sabatini filed a civil defamation lawsuit in state court, depicting Knouse and Lehmann as conspiring to bring him down and using the DEI survey as a pretext.

“My life was 100 percent destroyed,” he told the Globe. “This disrupted the lives of ... all my family members. ... My father will die before this is cleared up. So how am I supposed to get my life back other than to get the truth out there?”

Knouse later filed a countersuit, alleging sexual harassment and retaliation.

On social media, people in and outside academia either railed against Sabatini or fiercely defended him.

He saw support from some prominent academics who questioned his treatment by Whitehead. The former dean of Harvard Medical School, Jeffrey Flier, asked on Twitter, shortly after Sabatini’s ousting, if Sabatini had received a fair hearing. Harvey Lodish, one of the founding members of Whitehead, told the Globe he believed Sabatini’s punishment was too extreme.

Then, a number of weeks after the scandal exploded, in the fall of 2021, Sabatini had a welcome phone conversation with a friend that led him to think, perhaps, his future as a scientist wasn’t totally destroyed.

She was Dafna Bar-Sagi, executive vice president of NYU Langone Health, an academic medical center in Manhattan, and a cancer researcher who knows Sabatini’s father, a former head of the cell biology department at NYU.

After hearing Sabatini out, Bar-Sagi thought the public version of the Sabatini story was, at the very least, incomplete. She cared about the treatment and advancement of women in science, and also knew from experience that relationships and lab culture issues can be complex. “I just felt that maybe there is more to the story than meets the eye,” she said in an interview.

Given Sabatini’s scientific skill, she said she believed he could be valuable at NYU, but only if leadership at the school felt comfortable after reviewing the allegations.

Sabatini arranged through lawyers to provide NYU with Whitehead’s confidential investigative report, letters, texts, and e-mails.

In the coming months, NYU’s vetting of Sabatini fell largely to Bar-Sagi, two other top female executives, and an outside law firm. Bar-Sagi said she began by speaking to some former Sabatini trainees, as well as professional colleagues who knew Sabatini and his mentees. She said she came to think that the depiction of Sabatini’s lab as having a “toxic” atmosphere was wrong.

The team also thought the penalty applied to Sabatini was out of proportion, based on their preliminary review.

They brought their initial findings to Ken Langone, chair of NYU Langone Health.

My life was 100 percent destroyed. This disrupted the lives of ... all my family members. ... My father will die before this is cleared up. So how am I supposed to get my life back other than to get the truth out there?”David Sabatini

“In our opinion, due process had not applied,” Langone told the Globe. “We weren’t ready to make a deal with him, but we felt he was an outstanding talent and hadn’t done anything that would prohibit our interest in him.”

It was a head-snapping turn of events: Top scientists at another leading research institution had reviewed the case and reached a much more forgiving conclusion, one that gave Sabatini a chance to salvage his career.

NYU was considering offering him a non-tenured position for a trial period, with an out-clause so the school could freely dismiss Sabatini if more derogatory information surfaced.

Opinion was not unanimous among the school’s top leaders. Some NYU faculty did not want to be second-guessing the prestigious Whitehead Institute, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and MIT. University president Andrew Hamilton strongly recommended against bringing Sabatini on board, clearly an important voice in the controversy.

On March 1, 2022, Sabatini took a train to Manhattan. He had been invited to a formal dinner thrown by the Pershing Square foundation, a charity that provides grants to young researchers. Sabatini had done volunteer work for the foundation, one of the few groups that did not cut ties with him after the scandal.

When the co-founder of the foundation, billionaire philanthropist Bill Ackman, rose to offer some remarks, something surprising happened: Ackman spoke to the audience about the presumption of innocence, and David Sabatini.

Imagine if it were you, Ackman urged the crowd. Imagine if someone accused you and your career was over and there was no due process or chance to defend yourself.

When Ackman finished, people around the room began talking — talking about Sabatini. Word apparently spread that NYU was interested in him. By the end of April, the news reached Science magazine, which broke the story that NYU was in discussions with Sabatini over a faculty position.

The backlash on campus built quickly.

In late April, some 200 students and faculty from NYU’s Grossman School of Medicine poured into the streets in a high-profile demonstration against the school’s interest in Sabatini.

They held handmade signs: “Say No to Sabatini,” and “Students Against Sabatini!”

Hundreds of students and faculty members signed a petition to “collectively condemn NYU for the immense harm already done by even considering Sabatini’s employment.”

Several dozen of Sabatini’s former mentees tried to help his cause by endorsing a letter praising Sabatini and his lab’s culture, but the signees remained anonymous, for fear of career reprisals. In any case, the letter was overshadowed by the tsunami of opposition.

It was quickly obvious to NYU officials that hiring Sabatini was impossible in the face of such controversy and division.

Sabatini’s hopes for a second chance evaporated.

Advertisement

Epilogue

Today, all seven floors of Whitehead’s red brick building are humming again. Lehmann, now past her second year as the head of Whitehead and a faculty member with her own lab, says she has pushed for new hires and better communication channels with nearby research institutes. She also speaks of a renewed focus, and action plans, to foster “an inclusive, respectful, and diverse culture that inspires individuals to achieve their full potential.”

But some things haven’t changed.

Whitehead has added no formal management training, or made other institution-wide changes, that would prevent the emergence of over-powerful principal investigators. While Whitehead did implement additional antiharassment training, its rules regarding consensual workplace relationships still do not provide potential violators with a way to disclose a relationship and still keep their jobs.

But Lehmann insisted significant change is well underway. She has crafted Whitehead’s values statement and said Whitehead also adopted Jones Diversity’s recommendations, including for DEI training. And she said she strives for these cultural changes, while also aiming to hire the very best scientists.

Knouse resigned from Whitehead in June 2021, a couple months before the investigative report was released. She now runs her own lab inside the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and is also an assistant MIT biology professor.

But life over the past year has been far from easy. She has been the target of relentless attacks on Twitter as the woman who took down Sabatini. Some of the top responses to Google searches about her are about this scandal, not her science. “With every first interaction I have with someone,” she told the Globe, ”I have to think about what they’ve read about me.”

“This hurts so much,” she said in an interview during which she wept periodically.

Still, she works hard not to let the controversy or the ongoing court cases distract her from lab work. In November, she published a paper in Cell Genomics about her lab’s development of a novel technology that will allow researchers to investigate the function of every gene in a living mammal.

Sabatini is still looking for a way to pursue his passion for scientific discovery. He jumps at the chance to talk science when his former lab members reach out. They often do, but not enough to fill all his time.

He has fielded some job interest from scientific organizations interested in buying low on a distressed asset. Some are outside the US, opportunities that are hard to consider with his son living in Cambridge.

“I would like to run a lab again,” he said.

The ways his life has changed for the worse since the scandal are practically endless, he said. But some change is for the better. He said he has grown more empathetic and he is more appreciative of true friends than ever.

His marriage to Pernas did not survive. They separated in mid-2021, before the investigative report came out, and then divorced. He said they are still friends.

One warm afternoon last summer, Sabatini sat on a bench near a fountain in a small park near his home in Cambridge, and talked longingly about the thrilling science he used to do.

While he spoke, a small gray bird, a catbird, perhaps, somehow became trapped in the fountain. It beat its delicate wings against the water but could only circle the pool, like something going down the drain.

“That bird is going to drown if we don’t save it,” Sabatini said. He knelt at the edge of the pool, gently scooped up the bird in his cupped hands, and set it on the ground.

He said nothing, just watched the bird hop away, free.

To reach the Spotlight Team staff members who worked on this piece, please write to [email protected] or call 617-929-7483 or individually at [email protected], [email protected] and [email protected].

Tell us your thoughts and see reader feedback

Credits

- Reporters: Meghan E. Irons and Mark Arsenault

- Spotlight Editor: Patricia Wen

- Editors: Mark Morrow and Scott Allen

- Digital Editor: Christina Prignano

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development and graphics: John Hancock

- Photographer: Craig F. Walker, Erin Clark, and Jonathan Wiggs

- Photo editors: Leanne Burden Seidel and William Greene

- Lead photo: Jonathan Wiggs

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Audience engagement: Cecilia Mazanec and Jenna Reyes

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

© 2024 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC