Boston Globe Spotlight Team

Boston Globe Spotlight Team

Unfinished justice

The state’s high court in 2017 struck down a murder law that had condemned men who never killed to die behind bars. But what about those already facing that dire penalty? They are waiting.

They are men who killed nobody but have been condemned to die in prison. Men who never fired a shot or wielded a weapon, who may not even have been in the same room as the killing, or known anything about it.

And yet they have been convicted in Massachusetts of first-degree murder, and sentenced to the most draconian penalty under state law.

They live, and may die, in a strange corner of the state judicial system, convicted of an offense known as felony murder, which in rare cases allowed someone who joined in a serious crime but played no direct role in a killing, and may never have intended to harm anyone, to be punished as severely as the actual murderer.

Stranger still, the state Supreme Judicial Court ruled five years ago that the way these men were convicted was unjust, and abolished it.

But the high court did not make that ruling retroactive. That means there are men in this state who killed nobody but stand sentenced to die in prison.

How many? It is hard to know.

There is no database that tells us how many of the 1,012 people serving sentences of life without the possibility of parole in Massachusetts fit into this category. Most of them, in fact, are incarcerated for premeditated killings or murders of particular atrociousness. But a Boston Globe Spotlight Team analysis of hundreds of first-degree murder convictions going back to the early 1970s identified at least 23 people — all men — sentenced to life without parole despite not having inflicted physical violence on the victim. There could be others not captured in the Globe’s review.

Some of the people in this subset have died in prison. Of those whose race can be determined, all but one are Black or Hispanic.

They were not blameless before their incarceration. They were found to have participated in dangerous felonies, such as armed robberies, but no court ever said that they physically killed anyone or intended to. They were convicted of murder under a holding of our state’s common law that said if someone died during the commission of certain felonies, everyone involved in the venture was on the hook for first-degree murder, which carries an automatic penalty of life in prison without hope for parole. It is the death penalty slowly applied.

“Not only did I not take a life, I was not even present,” said Joseph Jabir Pope, a few months shy of 70 years old, in an interview at MCI-Norfolk state prison last November, 37 years into his life sentence.

When the high court in 2017 addressed the state’s felony-murder rule, the justices decided that to secure a murder conviction, prosecutors from that date forward would have to prove that defendants like Pope who committed no physical violence in fact shared the intent to kill.

But the court did not apply its historic reforms to those already sentenced under rules the court itself had just abolished. When California rewrote its felony-murder laws in 2018, it went further and made its reforms retroactive. While the court here could reconsider the question, and there are other possible legal remedies for those in Massachusetts left behind by the ruling, nearly five years have passed with no action.

And so these men remain behind bars, waiting either for a legal miracle or their deaths.

Paul Gunter is one of them. Born in Jamaica, he arrived in Massachusetts with his family as a teenager around 1980. In the early 1990s, he was working as a shelf stocker at Bradlees. He drove an old Toyota junker that he bought for maybe $600.

Then he was recruited as the wheelman.

It was March 21, 1991. A small group of alleged Dorchester cocaine dealers operating from an apartment in the Franklin Field housing development concluded they had been robbed. Two of them grabbed guns, according to court records, and set out to confront the men they believed had ripped them off.

The gunmen enlisted an acquaintance, the 25-year-old Gunter, to drive them in his car to a triple decker on Kenberma Road in Dorchester, about a mile-and-a-half away. Prosecutors later alleged that Gunter was part of the cocaine enterprise, which Gunter has denied. He was not convicted of a drug offense in this case.

Gunter waited in the car on the street listening to the radio while the gunmen went to an apartment.

The armed intruders didn’t find the thieves, or the drugs, at the address. But they did encounter others, and disaster swiftly ensued. One of the gunmen held a couple inside the apartment at gunpoint, as well as a man who happened to be visiting, a disc jockey named Jack Berry Jr. The other armed intruder, Corey Selby, went off in search of the thieves, who were not there. The intruders then retreated out of the apartment, but as the door was closing, Selby pushed it open, said, “Give this message” to the thieves, and fatally shot Berry, who had nothing whatsoever to do with the robbery or any drug dispute.

Police investigated and arrested the men involved. Even though Gunter never left the car, he was charged with first-degree murder, same as the shooter and the other armed accomplice, and faced a sentence of life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Gunter insisted that he didn’t know Selby would randomly execute a bystander. He says he certainly didn’t want or intend for that to happen. And he says he had no idea at the time of his arrest the extent of his criminal culpability.

“They brought us into jail,” Gunter recalled in an interview with the Globe, “and we’re sitting there, sitting there, and next thing I know they say, ‘You’re facing natural life,’ and I’m crying about leaving my family.”

Criminal intent to kill or do grievous harm is an essential element of murder prosecutions. In criminal cases in Massachusetts before 2017, however, there was a notable exception. Under the theory of first-degree felony murder, prosecutors did not have to prove that a participant in certain dangerous felonies had any specific intent to kill. It opened the law to some freak possibilities.

Imagine: A lone robber holds up a store. The thief, in this hypothetical case the Supreme Judicial Court discussed in a felony-murder ruling, trips and drops his gun. The weapon goes off accidentally and a bystander is hit. If the bystander dies, that’s felony murder — a death occurring during the commission of a dangerous felony. That’s life without parole.

“But if the victim survives,” the SJC noted, “the defendant is guilty only of the underlying felony, and is not criminally responsible for the shooting.” The shooting was, after all, an accident. “The defendant’s liability for the shooting rests, not on the defendant’s conduct, but on whether the victim lives or dies.”

To convict Paul Gunter of murder, prosecutors only had to convince the jury that by driving armed men to that apartment, Gunter was a willing participant in a dangerous felony, in this case armed assault in a dwelling. His intent to commit that crime was substituted, legally speaking, for the criminal intent required to support a murder conviction.

Gunter is incarcerated today in MCI-Concord, having served 31 years of a sentence scheduled to last until his death. He is 56.

One of the actual gunmen in his case testified for the government and was allowed to plead to the lesser crime of manslaughter, according to news coverage of the trial. He served about a decade in prison and was paroled more than 20 years ago, Department of Correction records say.

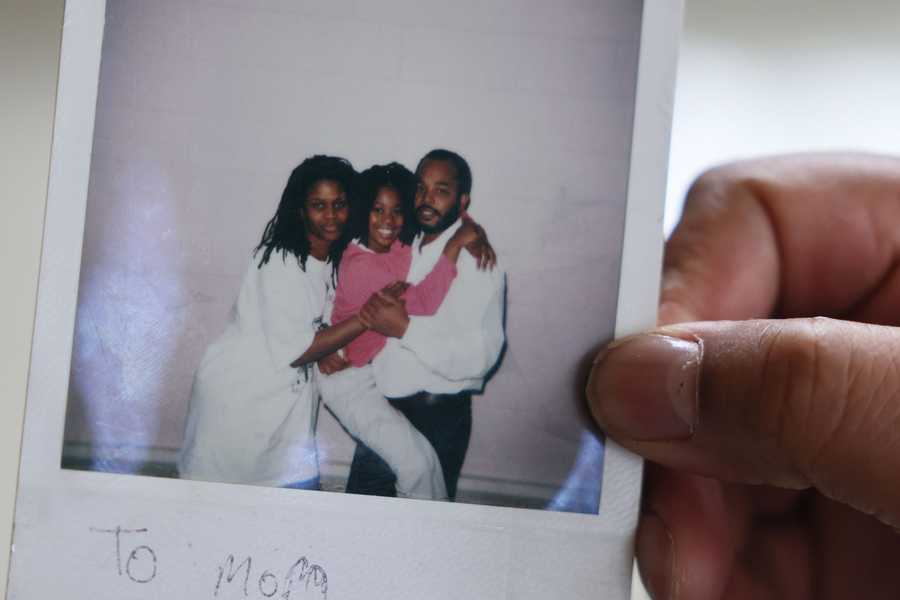

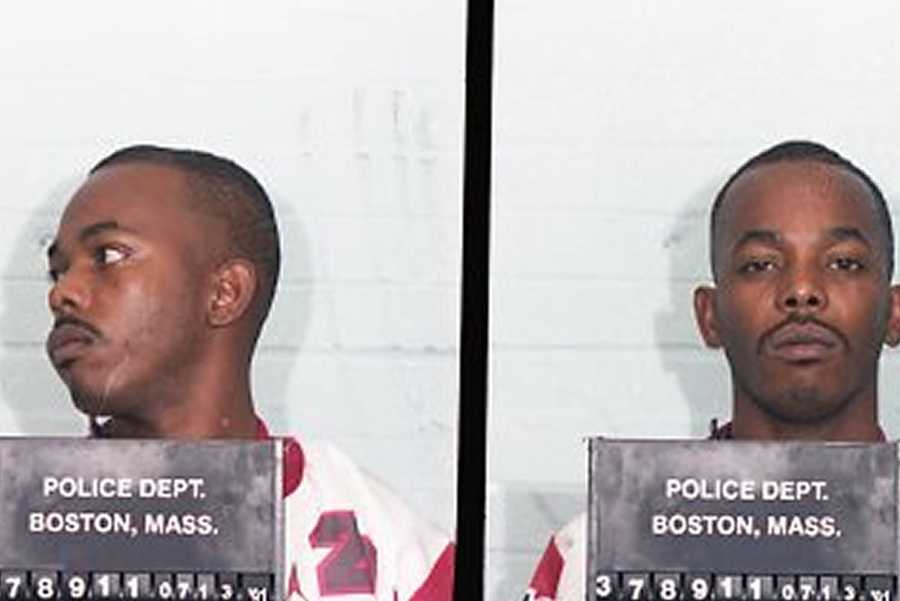

Paul Gunter held a photo of him with his family. Gunter, in his booking photo from the early 1990s. (Handout photos)

The vast majority of people convicted under the felony-murder rule are accused of committing the actual violence that killed the victim, and in many cases, acted alone. No central database exists to enable one to cull out the exceptions to this, and the Department of Correction will not release a list of everyone serving life without parole.

The Spotlight Team learned of some cases by reaching out to defense lawyers who handle such cases and the incarcerated individuals they represent. Many were young men when they committed their crimes.

The roughly two dozen individuals identified in the Spotlight Team analysis were handed automatic life terms without parole due exclusively to the felony-murder rule, despite having no role in the physical violence on the victim. In none of these cases did prosecutors have to prove the individual had any intent to kill or do grievous harm to someone, as they would if these cases came up now.

Some of these convicted men fought for years along traditional avenues of appeal to have sentences reduced or convictions overturned. In a few cases, the accomplice who actually did the killing got a lighter sentence, through a plea deal, with the opportunity for parole.

Where the punishment doesn’t fit the crime

Some people sentenced to life terms under the state’s controversial felony-murder rule have sought options for release — with mixed results.

William Allen

The latest: Governor Charlie Baker this year commuted Allen’s first-degree felony-murder sentence to second degree, opening a door for Allen, now in his late 40s, to apply for parole. Allen has maintained he never intended anyone to die and apologized for the robbery.

The crime: Prosecutors said Allen, then 20, and a friend broke into the home of a reputed Brockton drug dealer in 1994, intending to rob him. While Allen was in another room, the friend fatally stabbed the drug dealer. The killer pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was paroled more than a decade ago.

Frederick Christian

The latest: Christian benefited from landmark reforms a decade ago that enabled juveniles — who were tried as adults and convicted of first-degree murder in Massachusetts — to become eligible for parole. In 2014, the parole board approved his release from prison.

The crime: Christian was 17 when prosecutors said he and four others drove to a Brockton house in 1994 to rob drug dealers. Afterward, one of the men shot the driver and two other passengers without warning. The driver survived. Christian told police he did not know that his friend planned on shooting anyone.

Peter Cruz

The latest: Cruz died of renal failure in 2019 in his early 60s while serving a life sentence related to felony-murder charges, which he contested over the years. He had petitioned for release under the state’s medical parole program.

The crime: He was 41 when prosecutors said he and two teenagers plotted an armed robbery of a retail store employee in Holyoke in 1999. Cruz was not present during the holdup. But one of the teenagers fatally shot the employee who had chased the robbers, police say.

William E. Florentino Jr.

The latest: After four decades in prison, Florentino, now 64, had tried in 2018 to see if a state court would adjust his sentence to give him a chance at parole. But his request, occurring a year after the high court’s felony-murder reform, was denied.

The crime: Florentino was involved in a fatal holdup in an Everett liquor store on Dec. 16, 1977. Prosecutors said Florentino stole from the cash register, while his co-defendant held up the store’s owner. The co-defendant fatally shot a customer who happened to enter the store.

The rules for criminal sentencing in these extreme cases evolved slowly in the last decade. In 2013, the SJC struck down life without parole sentences for juveniles. In that decision, the ruling applied retroactively, giving people incarcerated for first-degree murder as teenagers the chance to one day apply for parole.

In 2017, another case with the potential to bring historic change arrived at the SJC. It was called Commonwealth v. Timothy Brown.

The case dated to the early morning hours of Oct. 23, 2009. Shortly after midnight, a group of friends was hanging around Brown’s one-bedroom apartment in Lowell, when one had the ill-fated idea to rob a pair of brothers he knew in a Lowell townhouse, according to court records. Four men agreed to commit the robbery that night. Brown did not. He stayed home.

However, the robbers asked Brown if they could borrow clothing to hide their faces. Brown loaned them some hoodies. One of the men asked Brown if he had a gun they could take with them. Brown, then about age 21, hesitated, but the robbers talked him into it, according to the SJC’s summary of the case. He loaned them a .380 pistol he kept under his mattress.

The crime went horribly wrong. The brothers targeted for the robbery, Hector and Luis Delgado, were killed in a brutal, chaotic scene. People in the townhouse tried to flee and hide. Hector Delgado was shot three times in his own room, and was left on his bed, gasping his final breaths. His brother, fatally shot in the abdomen, staggered a short distance before collapsing.

The assailants were caught and charged with murder. And so was the friend who had loaned them sweat shirts and a handgun — Timothy Brown. A court found that Brown’s assistance made him a participant in the underlying felony of armed robbery. And since two men died during the crime, Brown was convicted of first-degree murder under the theory of felony murder. He never went to the murder scene but was sentenced to life without parole.

The justices on the SJC agreed that Brown’s conviction was perfectly legal under the common law of the time, yet the outcome troubled them. Should such a peripheral figure in the crime serve life without parole? The court decided in “the interests of justice” to reduce Brown’s conviction to second-degree murder, which permits Brown to apply for parole after serving 15 years. It does not guarantee parole.

A faction of the SJC wanted to go further. It was led by Chief Justice Ralph Gants, a Harvard-educated former prosecutor, appointed a Superior Court judge by Republican Governor Bill Weld and to the SJC by Democratic Governor Deval Patrick.

Gants died suddenly in 2020, after a heart attack, at age 65. He is survived by his wife, Deborah A. Ramirez, a law professor at Northeastern University School of Law. Ramirez, in a Globe interview, said her late husband believed holding people liable for deaths they did not cause or intend “violated the core principle of individual blameworthiness that anchored our jurisprudence.”

“By that he meant our authority is only legitimate when we are holding you responsible for your own acts and not the acts of others,” she said.

Gants had foreshadowed this line of thinking two years before the Brown decision, in the case of Commonwealth v. Robinson Tejeda, which centered on the question of whether a participant in an armed robbery could be convicted of murder if his accomplice died during the crime.

In this case, which dates to 2012, Tejeda waited in the car while his two friends entered a house in Dorchester purportedly to buy marijuana from a local pot dealer. When it came time to pay for the drugs, one of the buyers, Christopher Pichardo, pulled out a pistol to rob the dealer, according to court documents. The dealer whipped out his own firearm. In an exchange of gunshots, Pichardo was fatally hit.

The question facing the SJC was whether Tejeda could be convicted of felony murder. On the one hand, someone did die during the commission of a dangerous felony in which Tejeda was found to have participated — an armed robbery. In this case, however, the victim was one of Tejeda’s associates.

The court’s 2015 opinion, written by Gants, signaled discomfort with the felony-murder rule, as an “exception” to the legal principle that people are held accountable for their own actions. In the end, the justices ruled that Tejeda could not be convicted of murder because, for technical legal reasons, the felony-murder rule did not apply in his circumstance. The court did not see this as an occasion to change the felony-murder rule itself.

Two years later, in 2017, the case involving Brown came up for the court’s review; it was much more on point. Reform-minded members of the court shared a sense of urgency that change needed to happen with Brown, because Justice Geraldine S. Hines, who supported reform, was bumping up against the court’s mandatory retirement age of 70, and would soon be leaving.

In the end, she was part of a 4-3 majority that brought a historic rethinking of felony murder in Massachusetts.

In writing for the majority, Gants said that the felony-murder rule had caused “convictions of murder in the first degree that are not consonant with justice.”

From the date of the ruling forward, the court ruled, no defendant would be convicted of felony murder unless prosecutors proved he or she acted with intent to kill or cause serious harm sufficient to cause a death. The ruling made Massachusetts one of a handful of states that have reformed felony-murder rules, either through the courts or, in the case of California, in 2018, by statute passed by the legislature.

Justice Frank M. Gaziano wrote for the minority on the SJC who opposed the change. He argued that the profound harm caused by a criminal act, even if not intended, should affect how severely we judge the crime. Gants’s approach, Gaziano wrote, “is predicated on an extremely narrow view of moral culpability or blameworthiness” and “diminishes the seriousness of violent felonies that result in the deaths of innocent victims.”

Gaziano’s argument may sound right to Christina Down-Robinson. In 1993, her brother Scott Down was fatally shot during a botched robbery at a Walpole McDonald’s. Two men were convicted for the murder, but only one of them shot Scott Down. The other, Samuel Michael Caze, is serving life without parole after a jury convicted him under the felony-murder rule.

Down-Robinson sees no reason to permit Caze another appeal based on the Brown ruling. Caze was the one who took the initial steps to plan the robbery, she said, even getting a job at the restaurant briefly allegedly so he could case the place. “There was a lot of thought and premeditation that went into this and that’s not something to be taken lightly,” she said.

Felony-murder reform in Massachusetts was specifically aimed at future cases, not those from past prosecution. On this the court drew a bright line: The reform would not even apply to the defendant in the case that made history, Timothy Brown. He remains incarcerated.

His mother, Kristine Brown, said it is incomprehensible that the landmark ruling involving her son did not apply to him.

“I’ll be totally honest. I get very bitter at the situation,” she said. “I think the punishment should fit the crime.”

The reason it was not retroactive, Gants suggested in his ruling, was that these were long-settled matters, and that perhaps prosecutors would have been able to prove a shared intent to kill in some of these cases, if required to do so.

“I recognize that a felony-murder case might have been tried very differently if the prosecutor had known that liability for murder would need to rest on proof of actual malice,” Gants explained, referring to a legal term, malice, that describes a defendant’s intention to cause death.

Hines, who declined to comment on the specifics of the court’s deliberations, said the court was concerned about undermining many cases that had been long decided. “People are going to criticize that — why didn’t you let people who have previously been convicted have the benefit of this?” she said in an interview. “That’s a legitimate question that people can ask about.”

Gunter says he learned about the Brown ruling while listening to the radio. His hopes soared that the ruling might give him a valid avenue for appeal, but then he was crushed to hear the ruling did not apply to people already convicted.

“I cried real tears that night,” Gunter said. He could not understand why the ruling did not apply to people like him. “It’s still puzzling to me. Why would they change that law and these guys who are sitting here [in prison] have to stay here?”

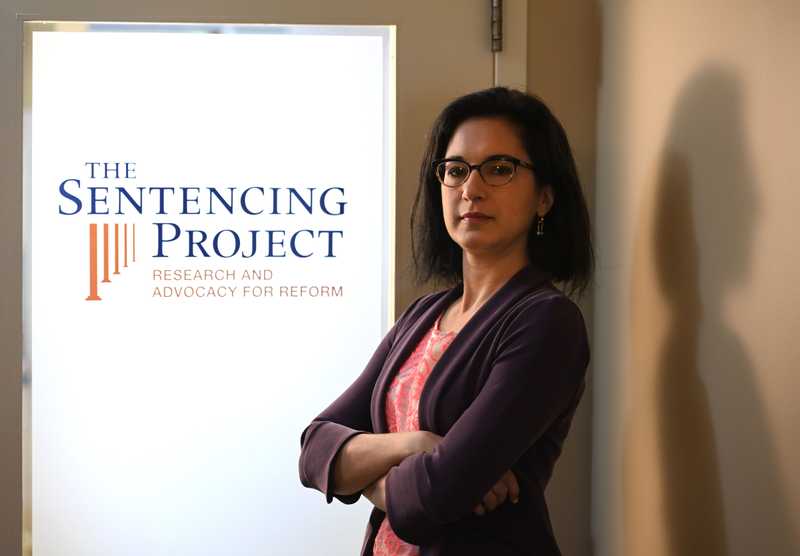

Massachusetts’ old felony-murder rule imposed the state’s harshest punishment on some who did not commit the worst crimes, said Nazgol Ghandnoosh, a senior research analyst for The Sentencing Project who authored a report this month on felony murder laws nationwide.

“The court’s 2017 decision narrows this injustice, but turns a blind eye to people languishing under the old law,” Ghandnoosh said. “The legitimacy of the criminal legal system suffers when courts deem a law unjust but do nothing to correct the extreme sentences imposed under that law.”

Where felony-murder sentences hit the hardest

Prior to 2017, Massachusetts was among 21 states that automatically imposed the most draconian sentences on people convicted of murder who did not intend to kill or participate in a killing.

⬢States where felony murder could mean automatic life without parole for some or all cases

Felony-murder reforms have taken hold in about a dozen states

States differ in how they apply felony-murder laws, but some, including Massachusetts, have made changes in response to criticism of disproportionate punishment. California is the only state that made its reforms retroactive.

⬢States that have implemented reforms

There are several potential ways to address prisoners who did not take a life and who were left behind by the Brown ruling, said Lisa Newman-Polk, a lawyer and prison reform advocate.

“The legislature could enact a law that makes the Brown decision retroactive or the governor could commute sentences,” she said. “Another possibility is for the district attorneys and [public defenders] to review these cases and jointly request that the convictions be vacated and replaced with lesser sentences.”

Commutations are very rare and politicians have proven reluctant to use their power to reduce sentences. Governor Charlie Baker in January issued his first two commutations, including one for William Allen, who was sentenced to life without parole for his participation in a 1994 armed robbery. Allen was convicted of first-degree murder despite not having inflicted any physical violence on the person killed in the robbery.

The SJC also has a case before it now that could change all that, perhaps making history again. The man behind the appeal is Joseph Jabir Pope and everyone agrees that he did not shoot anyone on the night that changed his life. But under the felony-murder rule, that did not matter.

A jury found Pope, a US Marine veteran from a big Boston family, guilty of participating in a 1984 armed robbery of brothers Efrain and Bienvenido DeJesus in a Dorchester home. Efrain was killed by a shotgun blast while Pope says he was on another floor of the house with Bienvenido. Under the felony-murder rule, Pope was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to die in prison.

Pope has maintained for decades that he was not involved in any armed robbery. He says he and a friend were at the Dorchester house to buy cocaine to resell. To buy, he said, not steal. It was a complicated case, and at trial the defense said that a third, unrelated man had done the shooting.

Throughout Pope’s trial, his lawyer consistently objected to the felony-murder rule, intending to preserve Pope’s rights to challenge his conviction if the common law on felony-murder was ever to change, as it eventually would in 2017.

Pope’s case is back now before the SJC. The case is still alive because Pope is too angry to let it die.

“Innocent prisoners generally do time differently than guilty prisoners,” he said. “I know that because I’ve been both. Those that are guilty tend to resolve themselves to their fate and on some level even find relief. With innocent prisoners there’s a hunger and rage that accompanies us on a regular basis.”

In 2020, Pope filed a motion for a new trial, in part based on witness statements that apparently were not turned over to the defense, and in part based on the fact that Pope had specifically challenged the fairness of the felony-murder rule at trial and noted the lack of evidence that he intended to kill anyone.

On that point, he was decades ahead of the SJC.

Pope said he essentially laid out Gants’s argument against felony murder in his own appeal, back in 1990. “Twenty-seven years later, using my argument and my reasoning and the actual cases that I cited, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court declared that it would never be all right for this to happen to anyone again,” Pope wrote last November. “I have been in prison for nearly 38 years and it is still all right for the Massachusetts Courts that this happened to me.”

In 2021, a single justice of the SJC reviewed Pope’s motion for a new trial and decided it had enough merit for the full court to consider.

With that appeal pending, a Superior Court judge approved a temporary stay to Pope’s life-without-parole sentence.

And last Dec. 9, Pope walked out of MCI-Norfolk, under sunny skies on a brisk winter day.

The day after Pope's release from prison, pending the results of his appeal, he went shopping for some necessities with his daughter. On the day of his release, Pope went to a mosque in Roxbury to pray. (Jessica Rinaldi/Globe staff)

He got into a car with his lawyer, Jeff Harris. As they pulled away, leaving the prison behind, Harris turned to his emancipated client and deadpanned, “Well that was pretty easy.” Getting Pope out of prison, even temporarily, was anything but easy — it took about four years of legal research and court filings.

When Harris dropped Pope off with family in Boston that evening, the men embraced. “There are no words, man,” Pope whispered in gratitude.

Pope is out of prison, but for how much longer?

Whether he goes back inside for the rest of his life is in the hands of the SJC.

Pope says the Brown ruling clearly should apply to his case. That position has drawn support from the Massachusetts Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, which said in an amicus filing, “For Mr. Pope and other defendants in his shoes, nothing is more meaningful than the chance to challenge their permanent imprisonment based on a legal fiction that has since been rejected.”

Oral arguments before the SJC were March 9. Pope sat in the front row of the gallery in a crisp suit, his overcoat and fedora on the bench beside him. His lawyer, Harris, fielded rapid-fire questions from justices. Nearly all the questions were related to Pope’s claims about prosecutors failing to turn over evidence in the 1980s. A few questions touched on the Brown decision. A decision is likely by this summer.

Now Pope waits.

“I’m hoping for the best,” Pope said. “But I always have to prepare for the worst and to a large extent, expect it. Because that’s always been a part of my journey.”

The court could allow him the new trial he seeks, or put him back in prison until the day he dies.

Tips and comments can be sent to the reporters at [email protected] and [email protected]. Contact the Spotlight Team at [email protected], or call 617-929-7483. Write to us at Globe Spotlight Team, 1 Exchange Place, Suite 201, Boston, MA. 02109-2132.

Methodology

The Globe Spotlight Team used the following methodology to find people who were convicted of first-degree felony-murder convictions, but did not directly play a role in the killing. Reporters constructed their own database because the state does not track those convicted of first-degree murder specifically under the felony-murder theory.

Reporters and researchers identified nearly 400 first-degree felony-murder cases reviewed by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court going back to the 1970s, using different sources, including www.findlaw.com. By law, all first-degree murder convictions are to get an automatic SJC review. Most of the rulings include a narrative of the crime drawn from trial evidence, helping reporters assess if the convicted individual was the actual killer. In many cases, news coverage of the crimes and trials was also reviewed.

Credits

- Reporters: Mark Arsenault and Meghan E. Irons

- Spotlight Editor: Patricia Wen

- Other reporting contributors: Lizbeth Kowalczyk, Deirdre Fernandes, Rebecca Ostriker

- Design and development: John Hancock

- Photographer: Jessica Rinaldi and Pat Greenhouse

- Photo editors: Leanne Burden Seidel and William Greene

- Video producers and editors: Anush Elbakyan and Caitlin Healy

- Animation: Dominic Smith

- Copy editor: Mary Creane

- Audience engagement: Christina Prignano

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula and Todd Dukart

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2022 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC