When travel was treacherous for Black people: The Green Book’s legacy in New England

People were packed inside the dining room at Camp Twin Oaks: Men in white button-down shirts and women in sundresses sat at tables covered in pressed tablecloths. They picked at the breadbaskets and entertained the young children while looking around for additional chairs as more people filled the space.

Someone had a camera. Everyone paused what they were doing, turned to it, and smiled. Flash. The image of them celebrating the languid summer days on the South Shore was forever preserved.

Guests who stayed in cottages at the resort could go horseback riding at nearby stables and bring their children to swim in the crisp blue sea at local beaches. Camp Twin Oaks, a go-to destination on the Duxbury-Kingston line for Black families, was just one location listed in the Green Book.

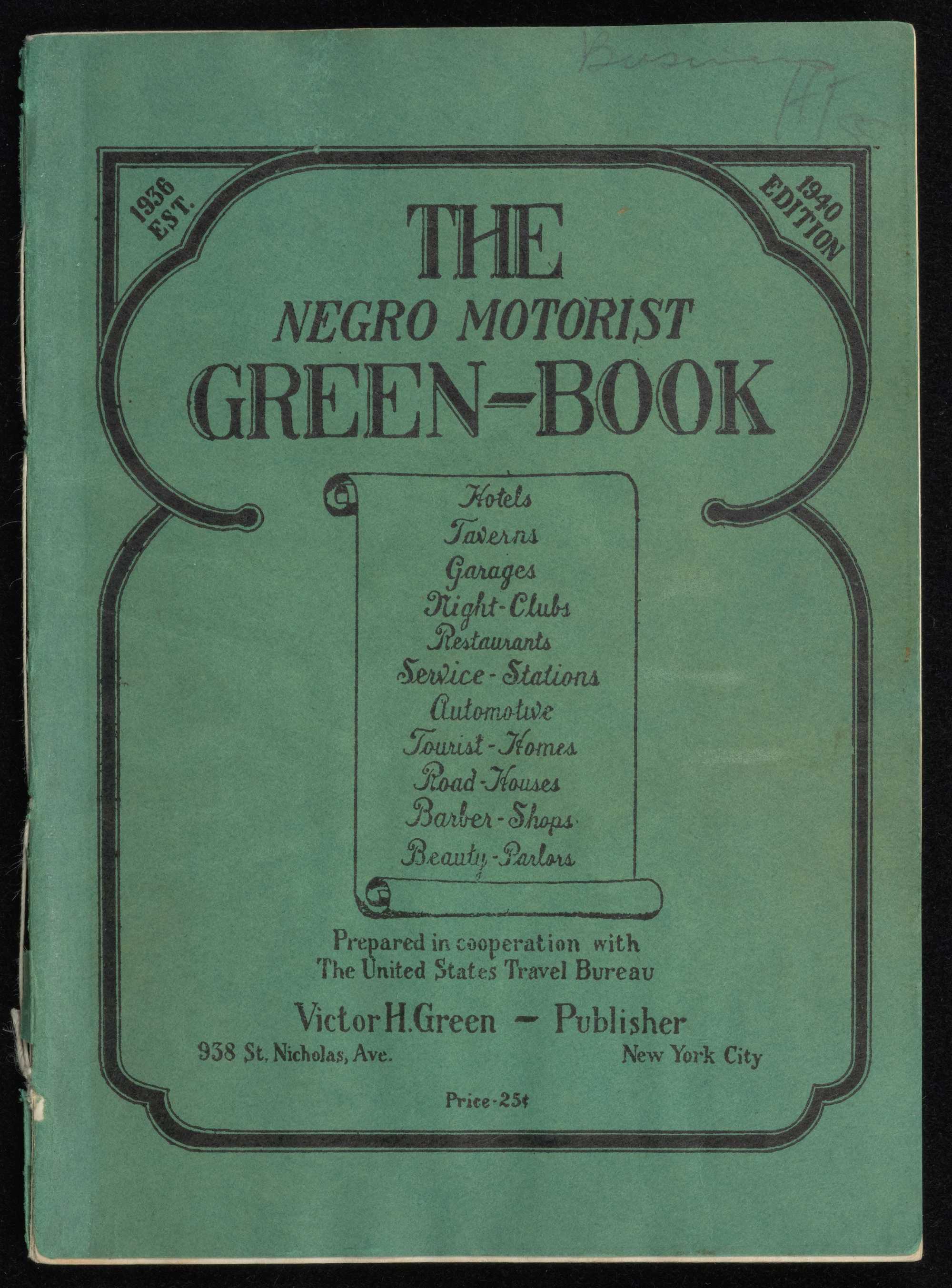

The cover of the 1940 edition of the Green Book. (The New York Public Library)

The Green Book was a travel guide listing hotels, restaurants, gas stations, barber shops, and other establishments across the country where Black travelers would not get hassled, turned away, or be put in dangerous situations. It was started in 1936 by Victor H. Green, a US Postal Service carrier who wanted his fellow Black travelers to be able to “vacation without aggravation.”

The Green Book was circulated when Black travelers had to navigate a segregated South, sunset towns, and de facto segregation in the North, with no guarantees of finding a safe place to eat or sleep. Such was the case in October 1955, when a Haverhill hotel owner refused to accept a reservation for a Black college professor despite his booking the room months in advance. And in July 1962, when seven hotels in Maine refused to provide lodging for Black actress Claudia McNeil when she was starring in a play at the Kennebunkport Playhouse.

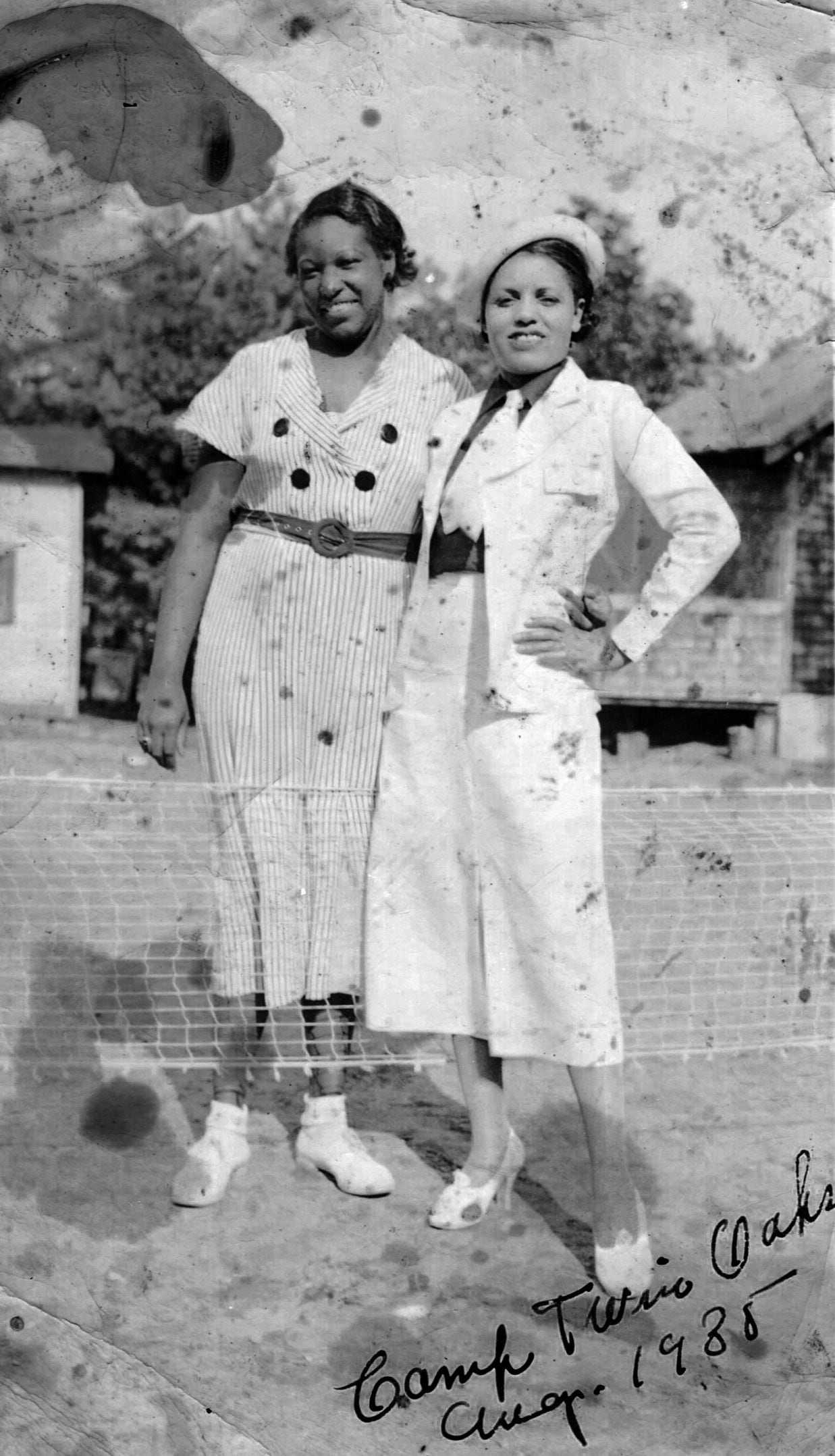

Guests dined at Camp Twin Oaks on the Duxbury-Kingston line. The resort was one of many vacation destinations listed in the Green Book. (Duxbury Rural & Historical Society)

Green’s guide wasn’t the first of its kind. Six years before the first Green Book was published, a woman in Connecticut named Sadie D. Harrison put together a nationwide directory of accommodations for Black travelers that was published in 1930.

Green’s guidebook only included New York businesses when it first came out but soon included other states and, eventually, other parts of the world. Businesses listed ranged from pharmacies to summer resorts to “tourist homes,” which were private residences where travelers could rent a room for a few nights.

After the 1964 Civil Rights Act outlawed discrimination in public places, the need for the Green Book subsided. The last edition was published in 1966. The phasing out of the Green Books, because they were no longer necessary, was one of Green’s dreams.

Advertisement

Guests posed for a photo at Camp Twin Oaks, circa 1930s. (Duxbury Rural & Historical Society)

“That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States,” he wrote. “It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment.”

Candacy Taylor, author of “Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America,” estimates that less than 5 percent of Green Book sites are still in business, and approximately 75 percent of the buildings they were housed in “are either gone or modified beyond recognition.”

The Globe created a database of Green Book sites in all six New England states. It contains approximately 350 listings that can be viewed by clicking on the dots on an interactive map. Globe reporters have also written stories about several businesses that were listed in the Green Book, some of which are still around today. If you have anecdotes about any of these places or photos to share with us, please let us know — we’d love to hear from you.

Massachusetts

The interior of the Sunset dining room at the Western Lunch Box, with proprietor Mary C. Jackson in the back left. (Boston Guardian/Library of Congress)

Western Lunch Box 415-417 Mass. Ave., Boston

The buildings at 415-417 Massachusetts Avenue used to house the Western Lunch Box, a restaurant in the Green Book. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

For one girl, Western Lunch Box was Nana’s house

Larrine King and her baby sister, Mary Ethel, leaned forward and peered out their grandmother’s upper-story brownstone window to engage in one of their favorite weekend pastimes: people watching.

People of all shades buzzed up and down the busy street. Some jetted by to urgent plans while others staggered under the weight of liquor. Several more, led by their empty stomachs, walked through the front screen door of Mary C. Jackson’s Western Lunch Box.

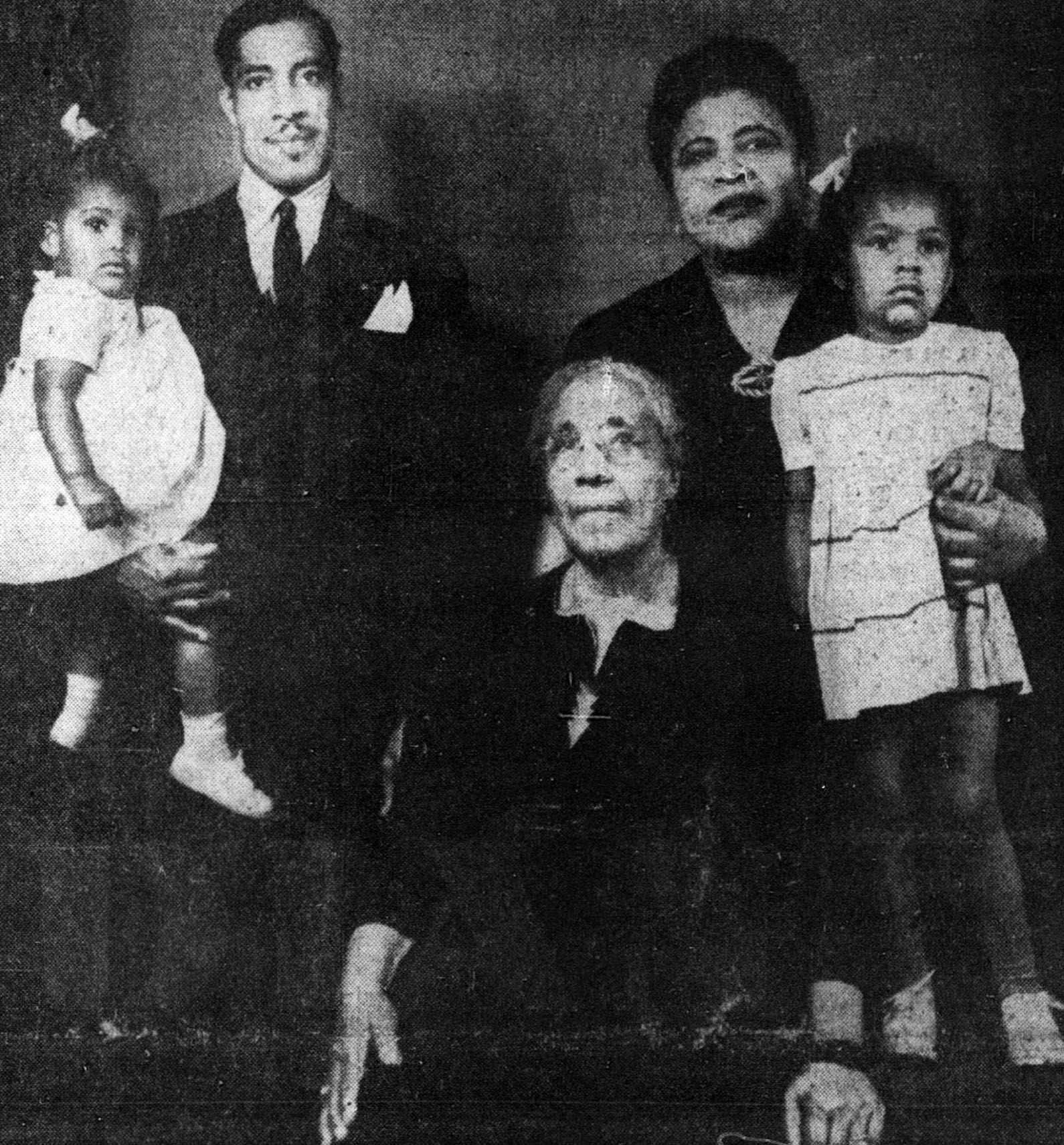

Mary C. Jackson (second from right) posed for a portrait with her family. Jackson was the proprietor of the Western Lunch Box on Mass Ave. From left, granddaughter Mary Ethel, son Lachester, mother, Jerrie Johnson, Jackson, and granddaughter Larrine. (Boston Guardian/Library of Congress)

To King, now an 84-year-old Sharon resident, Western Lunch Box wasn’t a renowned South End restaurant and guest house that hosted people from all over the country. It was Nana’s house.

It was where her grandmother’s gingerbread cookies melted into a chewy, “molassessy,” buttery concoction on her tongue. Where the savory, peppery smell of her grandma’s hot tamales seduced her nostrils. Where her fingertips wrinkled in the humongous tub of cool water as she and Mary Ethel rinsed dirt from the day’s hand-picked collard, mustard, and kale greens.

As King’s grandmother claimed in newspaper ads, Western Lunch Box was a “home away from home” for Southerners booking short and lengthy stays in Boston.

Before the actress and comedian Jackie “Moms” Mabley began donning her iconic housedress and bucket hat, she would linger near Jackson as she battered fried chicken for customers. Martin Luther King Jr., then a Boston University student, came in often because he was enthralled by Jackson’s ham hocks and greens. King remembered thinking once after speaking with Martin, “Maybe I could go to BU, too.”

Kornfield Pharmacy 2121 Washington St., Roxbury

At Kornfield Pharmacy in Nubian Square, Sharon Kamowitz (right), granddaughter of its second Jewish owner, Henry Shapiro, met current owner, Esther Egesionu, inside the pharmacy for the first time. Esther took ownership after her husband was killed. (John Tlumacki/Globe Staff)

Frappes, sandwiches, and elixirs. Kornfield Pharmacy was a local favorite.

At all hours of the day, Kornfield Pharmacy was a symphony of business. The jolt of a hand-crank cash register here. The ringing of a telephone there. The smoothing of medicinal powder on marble. Ching. Ring. Swoosh. Henry Shapiro was its hardworking conductor, and the comforting, busy medley lasted until his death.

From 8 a.m. to 11 p.m., “there were always people going in and out of the store,” said Sharon Kamowitz, Shapiro’s granddaughter. Children tugged at their parents’ clothes as they picked up their prescriptions, begging them to buy them one of the decadent frappes — a sugary concoction of milk, soda, and ice cream ― the store sold.

Hungry passersby would snag cold tuna or egg salad sandwiches from the lunch counter. Intoxicated clubbers from Aga’s Highland Tap across the street sauntered into Kornfield Pharmacy for another round of liquor, purchasing non-medicinal elixirs over the counter in inconspicuous paper bags.

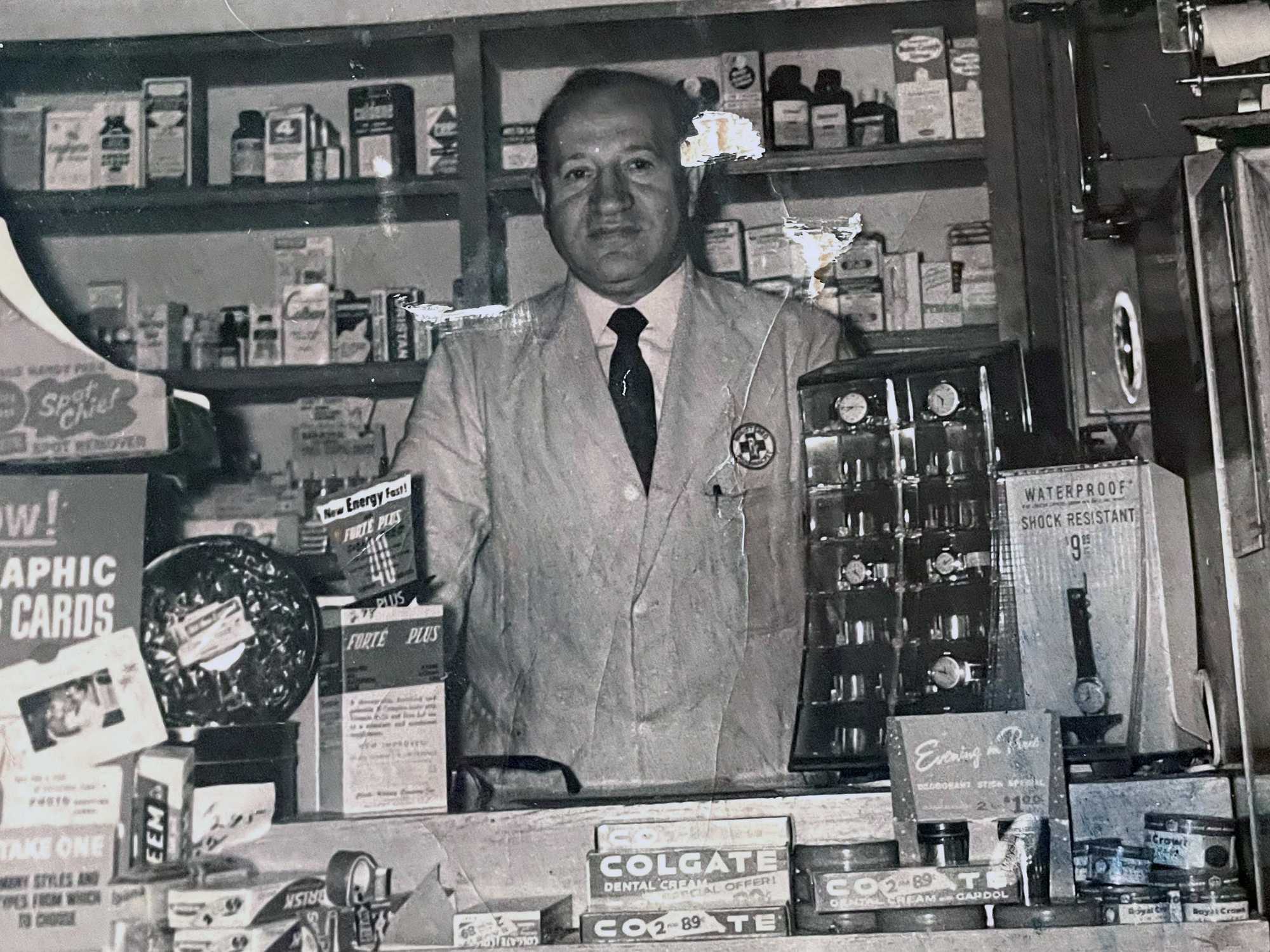

Henry Shapiro behind the counter of Kornfield Pharmacy. The photo was taken at some point in the 1950s. (Sharon Kamowitz)

Shapiro immigrated to Boston from what is now considered Ukraine dreaming of possibility. He applied to Harvard University’s medical program to become a doctor. But when he applied, he was told that “they had too many Jews,” his daughter, Elaine Bloom, told the Globe.

Shapiro didn’t give up on his dream. He went for the next best thing, which didn’t require a degree at the time: pharmacy. He worked at and later bought Kornfield in Lower Roxbury’s thriving Jewish community. While around 80 percent of the businesses in the Green Book are Black-owned, the remaining ones were sometimes owned by other marginalized groups, including Kornfield, which, under Shapiro’s stewardship, became a favorite pharmacy for locals.

His customers called him “Doc.”

Exterior of the Kornfield Pharmacy, taken in the 1950s. (Sharon Kamowitz)

Slade’s 958 Tremont St., Boston

Longtime patrons shared a laugh at the bar during jazz night at Slade's Bar and Grill in Boston. The historic establishment, a fixture on Tremont Street since 1935, has hosted the WeJazzUp band for nearly 25 years, continuing its legacy as one of Boston's enduring venues from "The Negro Motorist Green Book" era. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

Since opening in 1928, Slade’s has been a haven for the community

By Devra First

It’s a Tuesday night at Slade’s Bar & Grill, and the band is kicking into high gear. In the blue light, patrons sip drinks, eat Slade’s famous chicken wings, and nod along with the music. Some members of the ensemble, WeJazzUp, have been playing this venue for decades. Some are Berklee College of Music students sitting in for the night. Most of the customers are regulars.

A man posed in front of Slade's barbeque chicken restaurant on Tremont Street 1935-45. (Winifred Irish Hall/Northeastern)

“They call this the Black Cheers,” said Sonya Yancey, who has worked at the historic restaurant and nightclub for about 20 years. “Everybody would come here after work. We had a lawyer who sat at the bar and would give free legal advice. We had a doctor who would pop in every now and again. We had some of everybody once upon a time.”

Muhammad Ali. Ted Kennedy. Martin Luther King Jr. Bill Russell of the Celtics, who owned the place in the 1960s, nearly 7 feet tall in his burgundy suit. All passed through the doors of Slade’s, which opened in Boston in 1928 in a different location, under the name Slade’s Barbecue. The restaurant even employed Malcolm X as a server when he needed a job to get out of jail, according to current Slade’s owner Britney Kyle Papile.

Mother’s Lunch 510 Columbus Ave., Boston

The building at 510 Columbus Ave. in Boston where Mother's Lunch used to host many famous musicians. (John Tlumacki/Globe Staff)

Mother’s Lunch: where famous jazz artists practiced

Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Andy Kirk, and J.C. Higginbotham. They are just some of the jazz musicians who passed through Mother’s Lunch, a venue in Boston’s South End that had rooms for rent and kept intimate, conducive spaces for musicians on tour.

Mother’s Lunch was one of many packed brick rowhouses on Columbus Avenue but it stood out because it offered more entertainment options than the rest. It wasn’t just a place musicians could stay when they were in the city. Mother’s Lunch rented out a rehearsal space and had a nightclub called the Tangerine Room on its second floor, where jazz artists played until the night sky turned gray and then a clear, pale blue.

There was a downstairs restaurant, and when the city warmed in the summer months, patrons spilled into the street when it turned into a relaxed outdoor cafe. For a while, Armstrong’s band rehearsed at the venue daily and Ellington’s group passed through on their summer tours. The establishment offered a nurturing space for Afro-Cuban jazz, bebop, big band jazz and other complex compositions.

Advertisement

“With the jazz and nightlife, Mother’s became a prominent location and was the most important and best of a series of running houses in that area,” Jazz historian and writer Richard Vacca said.

Mother’s Lunch was owned by Wilhelmina “Mother” Garnes, a Black businesswoman from Ohio who ran it until 1956.

While Boston hotels began admitting Black people in the 1930s, many Black musicians would choose to stay at Mother’s Lunch over the other rowhouses in the South End.

Connecticut

A mural at Fulton Park in New London Conn., with an image of Sadie Harrison. (David L. Ryan/Globe Staff)

Hempstead Cottage 73 Hempstead St., New London

The exterior of 73 Hempstead St. in New London, the former home of Sadie Harrison. It is featured on New London's Black Heritage Trail. (David L. Ryan/Globe Staff)

Before the Green Book, there was Sadie D. Harrison’s trailblazing Black travel guide

My Dear Madam:

Could you tell me if there is a colored boarding house in New London? I expect to be driving through November 13 and would like to spend the night. If you know of such a place that you could recommend, I would appreciate the address.

Very sincerely yours,

W. E. B. Du Bois

Du Bois had asked the right person where to stay in the port city in southern Connecticut. Sadie D. Harrison ran a tourist home in one of the city’s first black neighborhoods, a two-story, wood-frame house called Hempstead Cottage.

Her mind turned as she read over the letter, dated Nov. 8, 1929. Du Bois didn’t know this, but for years Harrison had been creating a hotel guide for Black people traveling through the United States.

Harrison responded to the civil rights icon the next day, typing out her letter on Hempstead Cottage letterhead, telling him she’d be pleased if he stayed at the cottage.

Putting together the hotel guide was a labor of love for Harrison, who spent countless hours writing to local chambers of commerce and city officials across the country and compiling the names and addresses of hotels and tourist homes that welcomed Black guests.

This photo of Sadie D. Harrison appeared in a 1928 issue of "Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life," an academic journal published by the National Urban League. (The Internet Archive)

Publishing the book was simply one accomplishment in her intrepid life. Years before, Harrison had left her husband in Indiana, filed for divorce, and sought a restraining order against him because she was “afraid that he might do her bodily harm.” She moved to New London, purchased Hempstead Cottage, and became actively involved in the town’s Negro Welfare Council and the New England People’s Finance Corp., which provided banking services and loans to the Black community.

Harrison teamed up with Edwin H. Hackley, a Black lawyer and writer in Philadelphia, and published “Hackley & Harrison’s Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers” in 1930. It listed accommodations in 300 cities throughout the United States and Canada, including more than 200 hotels and upwards of 1,000 tourist homes.

In the introduction to the book, Harrison reprinted the letter she received from Du Bois (with his permission, of course). She said his letter, “aptly illustrates the practicality and universal need” for her newly published hotel guide.

Tom Schuch, a New London historian and researcher for the city’s Black Heritage Trail, said Harrison’s hotel guide laid the groundwork for the Green Book and other Black travel guides, “although she rarely gets any credit.”

“Prior to what she did, it was basically word of mouth,” Schuch said. “She got it into print, which made it available for people.�”

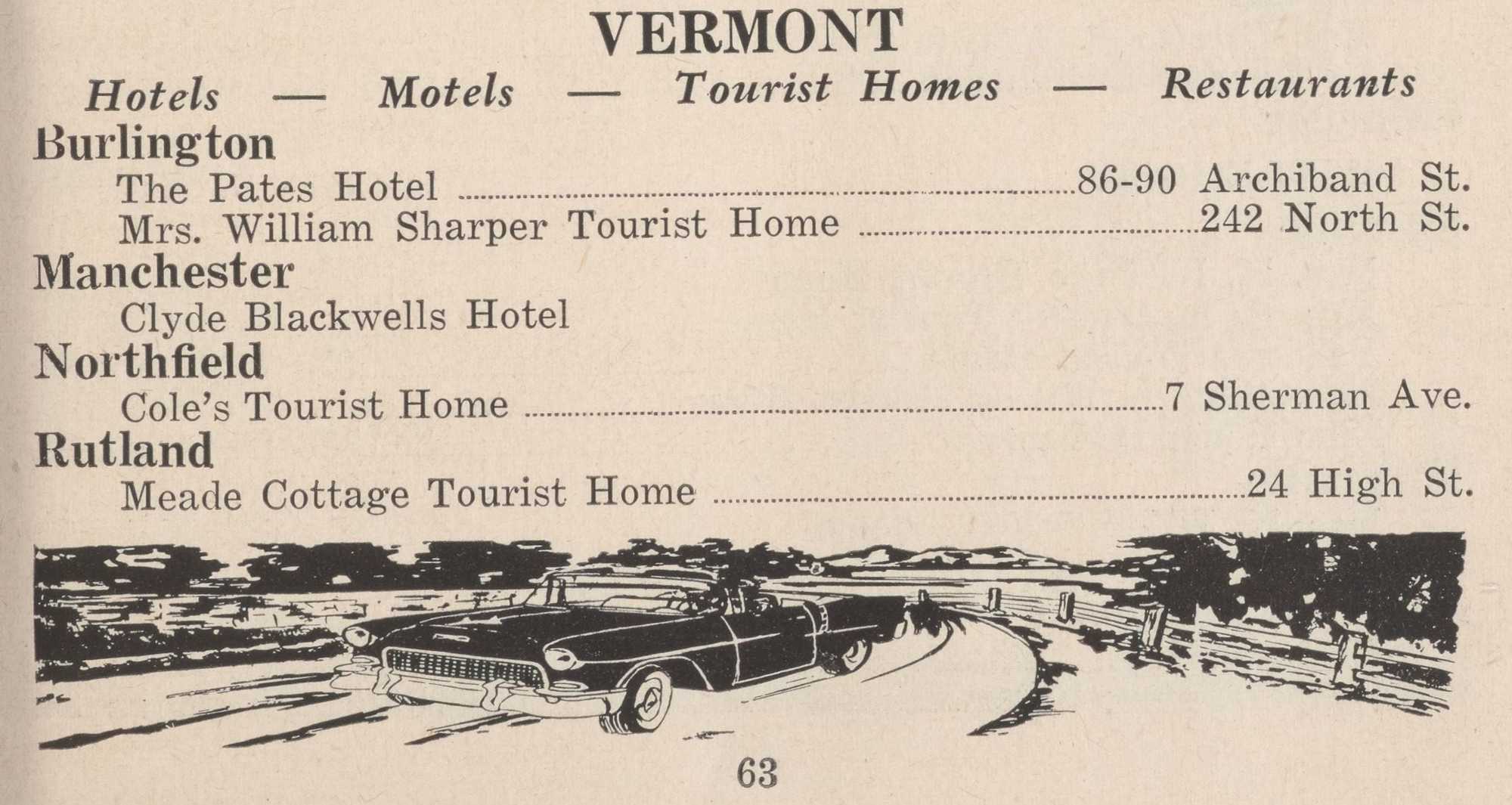

Vermont

The Pates Hotel, also known as "The Pates," was at 86-90 Archibald St. in Burlington, Vt. It was listed in the Green Book from the 1930s until the last edition was published in 1966. (Rebekah Mortensen)

The Pates Hotel 86-90 Archibald St., Burlington, Vt.

The listing for The Pates in the 1956 edition of the Green Book. (The New York Public Library)

A porch full of memories at The Pates Hotel: Vermont’s haven for Black travelers

Maxine Leary has fond memories of the time she spent doing bookkeeping work at The Pates Hotel as a teenager in the 1940s. On Saturday mornings during her freshman year of high school, she walked over to the two-and-a-half story building, which looked like several houses stitched together, knowing she’d get to spend time with one of its owners, Cleta Pate.

Pate was a Filipino native who ran the hotel with her husband, Frank, and lived there with her family. When Leary arrived, Cleta would bring out the paperwork and sit with her at the dining room table while she crunched numbers for a couple of hours. Leary remembers that Cleta was a warm and easygoing person and they laughed a lot together.

“I loved her,” Leary said.

Advertisement

The hotel had a big porch in the front where people could gather and where Frank, who was Cleta’s second husband, would sometimes spend time relaxing with his step-grandchild. Occasionally, celebrities passed through. In the summer of 1930, about a decade before Leary was employed there, a Black baseball team called the Burlington Colored All Stars took up residence there for the summer. One of the players on the team was Jesse “Nip” Winters, one of the best left-handed pitchers from that era.

Cleta purchased the building in the 1920s with Frank Pate, a military veteran who’d served in the US 10th Cavalry, an all-Black Army regiment known as the Buffalo Soldiers. She expanded it over the years to become both a boarding house and a hotel.

Long after Leary left, Cleta’s son from her first marriage, Alfred, continued to run the family business as a Green Book hotel until the 1960s, and then turned it into an apartment house.

Maine

Bob Greene in front of the former Thomas Tourist Home (far right), a Green Book destination for Black travelers in Maine. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

Thomas House Tourist Home 28 A St., Portland, Maine

A green lantern led Black travelers to Thomas Tourist Home

PORTLAND, Maine — When the sun set on Portland’s West End and the streets went quiet, the Green Lantern Grill at the Thomas Tourist Home came to life. Black soldiers, sailors, and railroad porters listened to Nellie Lutcher and Dinah Washington on the jukebox. They relaxed over cards, and they ate warm, filling meals before heading upstairs to rest at one of the few places in the city that welcomed Black travelers.

The Thomas Tourist Home was a Green Book destination used by many of the Black porters who worked out of nearby, long-gone Union Station. (Suzanne Kreiter/Globe Staff)

“Everybody knew about the Green Lantern,” said Bob Greene, a Black historian and eighth-generation Mainer.

The Thomas Tourist House was a modest, cream-colored, two-story rooming house where a green lantern hung in a bay window, lit in good weather and bad, to welcome Black members of the military and railway workers from nearby Union Station. They laughed, they gossiped, and if they wanted a drink, they brought their own. Maine did not serve liquor by the glass at the time.

The place was run by Benjamin Thomas, a Red Cap who assisted railroad passengers, and his wife, Edith, whom the government paid to feed Black service members during World War II. The couple also opened the Marian Anderson USO, named after the famed Black singer.

There is no plaque at the Green Lantern Grill, and its history is not widely known. But today, according to Kate Lemos McHale, executive director of Greater Portland Landmarks, “it’s part of a bigger story that needs to be told.”

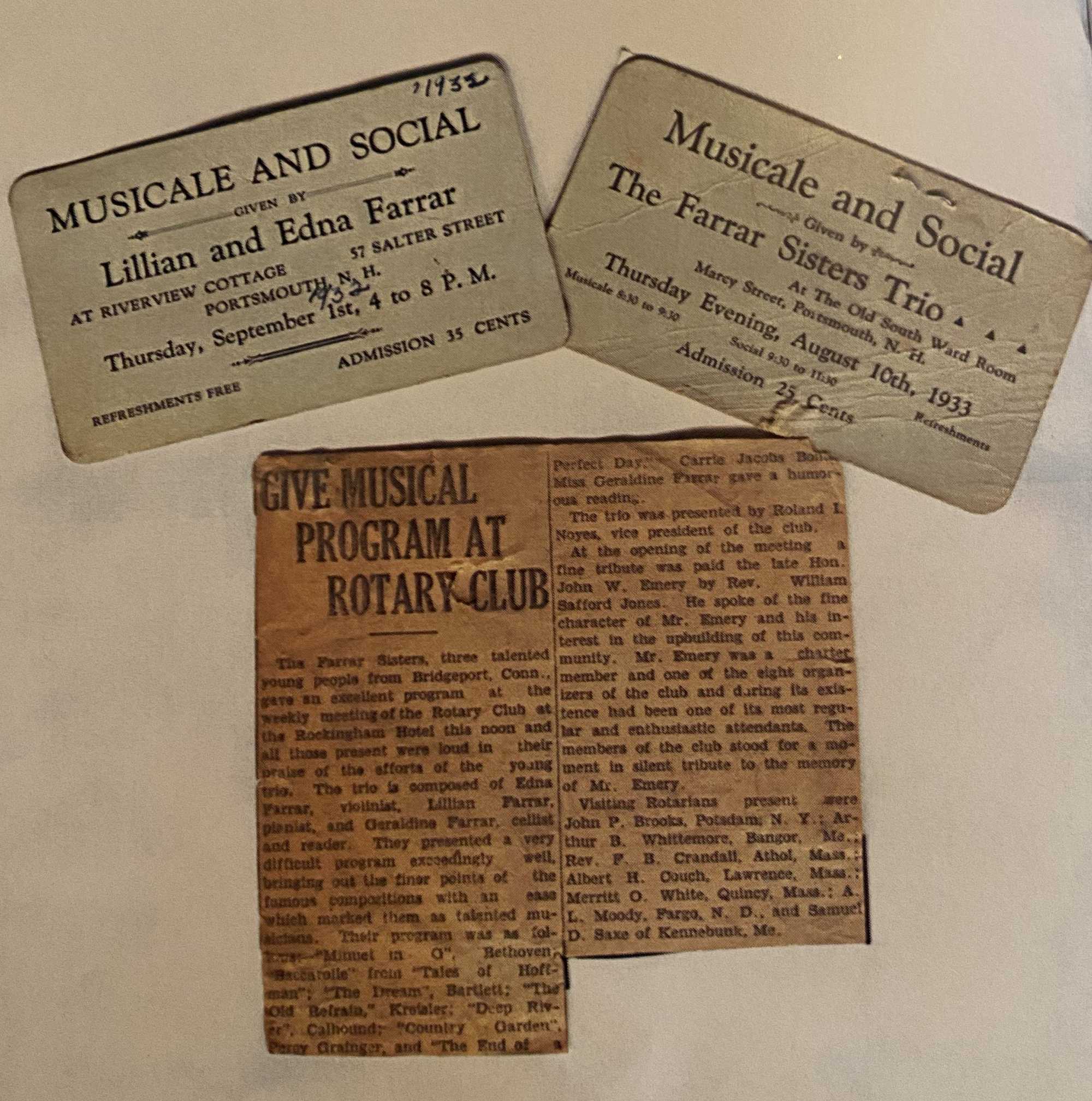

New Hampshire

This private residence, at 57 Salter Street in Portsmouth, N.H., was the site of the Blank's Riverview Cottage. (Pat Greenhouse/Globe Staff)

Riverview Cottage 57 Salter St., Portsmouth

A peaceful snapshot of Blank’s Riverview Cottage

By Amanda Gokee

Blank’s Riverview Cottage was shrouded in a restful calm that Baxter F. Jackson welcomed after days of traveling through New England and Canada, according to an essay he wrote in the 1941 Green Book.

He left for his trip on a Sunday in July with the Southernaires playing on his car’s radio. The sun was warm as he drove on roads that reminded him of ribbons, passing farmhouses and white birches as he drove through the countryside.

When Jackson reached the cottage, he had already visited Hanover, N.H., home to Dartmouth College, in addition to stops in Vermont and Quebec. He reached Portsmouth after spending two days in Old Orchard Beach, Maine, with a friend who dragged him to the beach despite it being a bit too cold to swim.

At the picturesque waterfront cottage nestled on a dead-end street, Jackson had a chance to relax. Outside, wooden shingles shielded the house from the elements, while the interior contained upscale decor, including a floral-patterned china serving dish and ornately carved side tables made of wood and marble.

He met some friends from New York there who were just beginning their vacation and they feasted on meals made by Annie B. Blanks, who ran the cottage along with her husband, Eben F. Taylor.

“If a man digs his grave with his teeth as I have been told, I hope I can dig mine with Mrs. [Blanks’] cooking,” he wrote in the essay.

In the evening, he listened to Eben talk about his younger years in the Navy, completely absorbed by the stories. He felt like his days at the cottage, frequented by musicians and Black travelers, passed too rapidly. Soon, he was on his way home dreaming of the vacation he’d take next year. He hadn’t settled on his next destination, but he hoped it would be as pleasant as the last.

The Farrar Sisters Trio performed in Portsmouth, N.H., in 1933, including at Blank's Riverview Cottage, according to the historical newspaper clippings and documents pictured. (Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire)

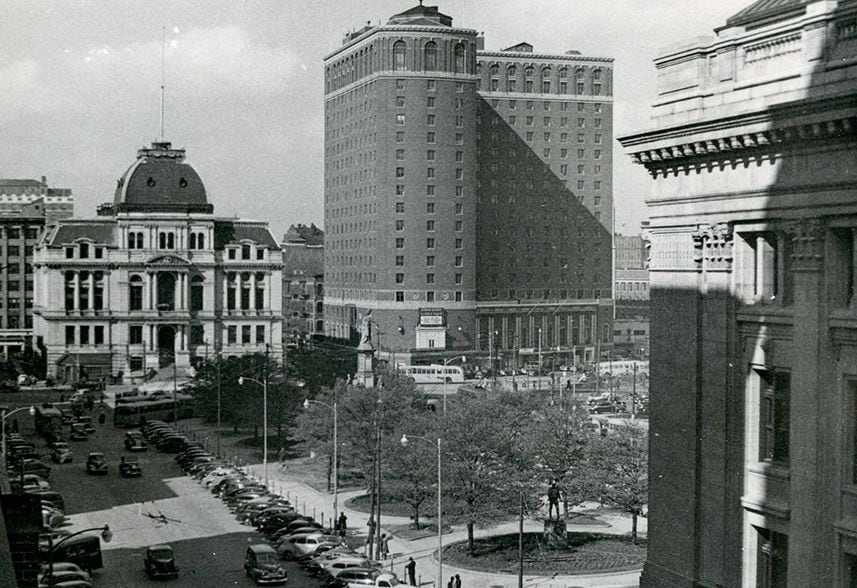

Rhode Island

The Biltmore Hotel and neighboring buildings, seen from across a plaza in Providence. (Providence Public Library)

Biltmore Hotel 11 Dorrance St., Providence

Graduate Hotel in Providence, which was previously named the Biltmore Hotel. The Biltmore was listed in the Green Book, which was a travel guide for Black Americans during the time of Jim Crowe . A view of elevator at top. (Jonathan Wiggs/Globe Staff)

Velvet, velour, and high fashion at the Biltmore Hotel

By Alexa Gagosz

A Black model in a floor-length coat walked down a catwalk. The coat swished back and forth when she moved, the fur-trimmed hem brushing against her ankles. Another model strutted in a dark, glittery dress. Others wore velvet and velour outfits created by some of the leading designers in the United States and Europe for a high fashion show hosted by Ebony magazine at the Biltmore Hotel in 1970.

It was Ebony’s 13th annual show, which had been seen in 78 cities from coast to coast since its inception. The show’s theme focused on a liberated look in various styles — from soft and casual to the most elegant, wrote fashion writers at the time.

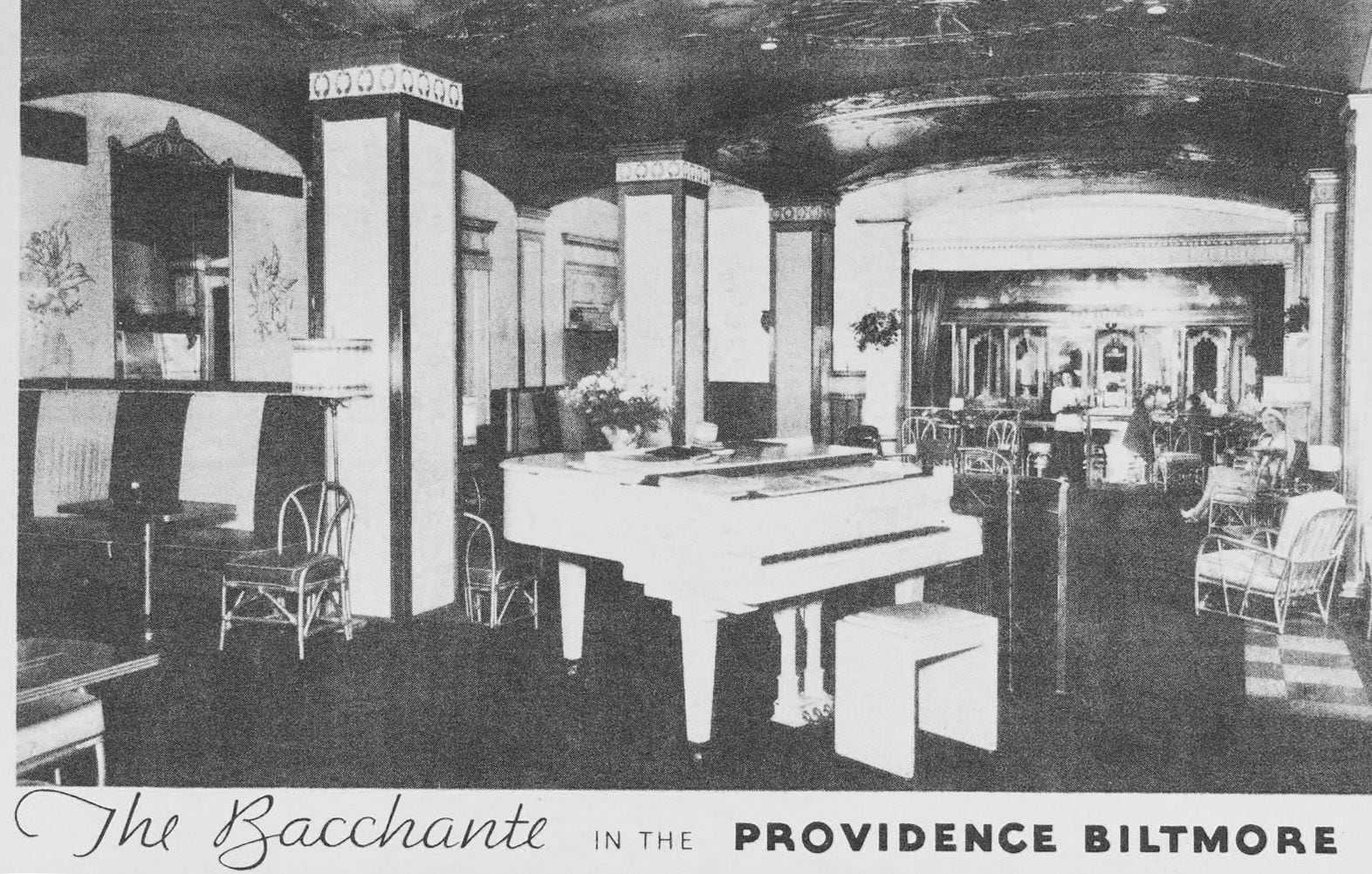

For those who were in the know or worked inside the luxurious Biltmore, having people of color at the hotel had long been the norm. The Biltmore hosted politicians, Rolling Stones bandmates, and socialites. But, even before the Civil Rights Movement, the Biltmore welcomed both Black and white guests at a time when discrimination at hotels was common.

“This was everything a traveling businessman would need access to,” said Catherine Zipf, executive director of the Bristol Historical & Preservation Society.

Interior view of the Bacchante in the Biltmore Hotel in 1950. (Providence Public Library)

The Biltmore Hotel stands 18 stories tall over downtown Providence and directly next to City Hall. It opened in 1922, with an opulent chandelier hanging from the ceiling and an awe-inspiring glass elevator rising from the center of the gold-and-marble lobby.

The Biltmore was acquired by Sheraton Hotels, which paid to be listed in the Green Book from 1947 to 1955.

Today, there are no historical markers in the hotel noting it was open to Black travelers at a time when most luxury hotels were not, and many members of its current staff and leadership are not aware it had been listed in the Green Book.

Credits

- Reporters: Emily Sweeney, Tiana Woodard, Devra First, Auzzy Byrdsell, Brian MacQuarrie, Amanda Gokee, Alexa Gagosz

- Editors: Hillary Flynn, Lylah Alphonse

- Data editor: Yoohyun Jung

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Pat Greenhouse, Suzanne Kreiter, David L. Ryan, John Tlumacki, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editors: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Design, development, and graphics: John Hancock

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editor: Michael J. Bailey

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Adria Watson, Sadie Layher, Cecilia Mazanec

- Audience editor: Heather Ciras

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC