BROKEN PROMISES, UNFULFILLED HOPE

Could a Two-Generation approach to education work in Boston?

HUTTO, Texas — As papas con chorizo sizzled on the stove in Selena Osuna’s small, two-bedroom apartment, the 25-year-old single mother sidled up to her older daughter at the kitchen table, a “Harry Potter” book laid before them. Legs tucked underneath her, Maliah, 8, tracked words on the page with her right pointer finger as Osuna helped to hold the book flat.

“Harry,” Maliah read, her Rs sounding like Ws, “watched the goblins white — ”

“Weighing,” Osuna interjected. “That one’s a hard word.”

“Weighing a pile of rubies as big as glowing coals,” Maliah finished, her long, dark hair tucked behind her ears, as her younger sister, Jae, 5, listened.

The evening routine, while critical to her girls’ development, didn’t come easily for Osuna, who has a part-time job and her own studies as a college sophomore. She balances her hectic schedule with the support of a program in nearby Austin that pays parents to go to school.

The idea driving this approach isn’t hard to explain. Students simply do better, academically and socially, when their parents have the kind of support that eases the constant worry about making ends meet. And their parents get a fair shot at setting an example of success.

“It’s allowed me to be more present and not have to worry about the weight of everything else,” Osuna said.

Austin’s experiment is part of a growing trend to lift families out of poverty known as a two-generation, or “2-Gen,” approach. Over the past two decades, these programs have increasingly sought to support parents and children by combining free tuition or career development with other assistance such as housing or child care. The goal is to create lasting economic growth in low-income communities.

Experts said programs such as this one, which provides child care scholarships and $500 monthly stipends, could hold valuable lessons for Boston, where many Black, and, increasingly, Latino, students have yet to experience Boston Public Schools as an engine of upward mobility.

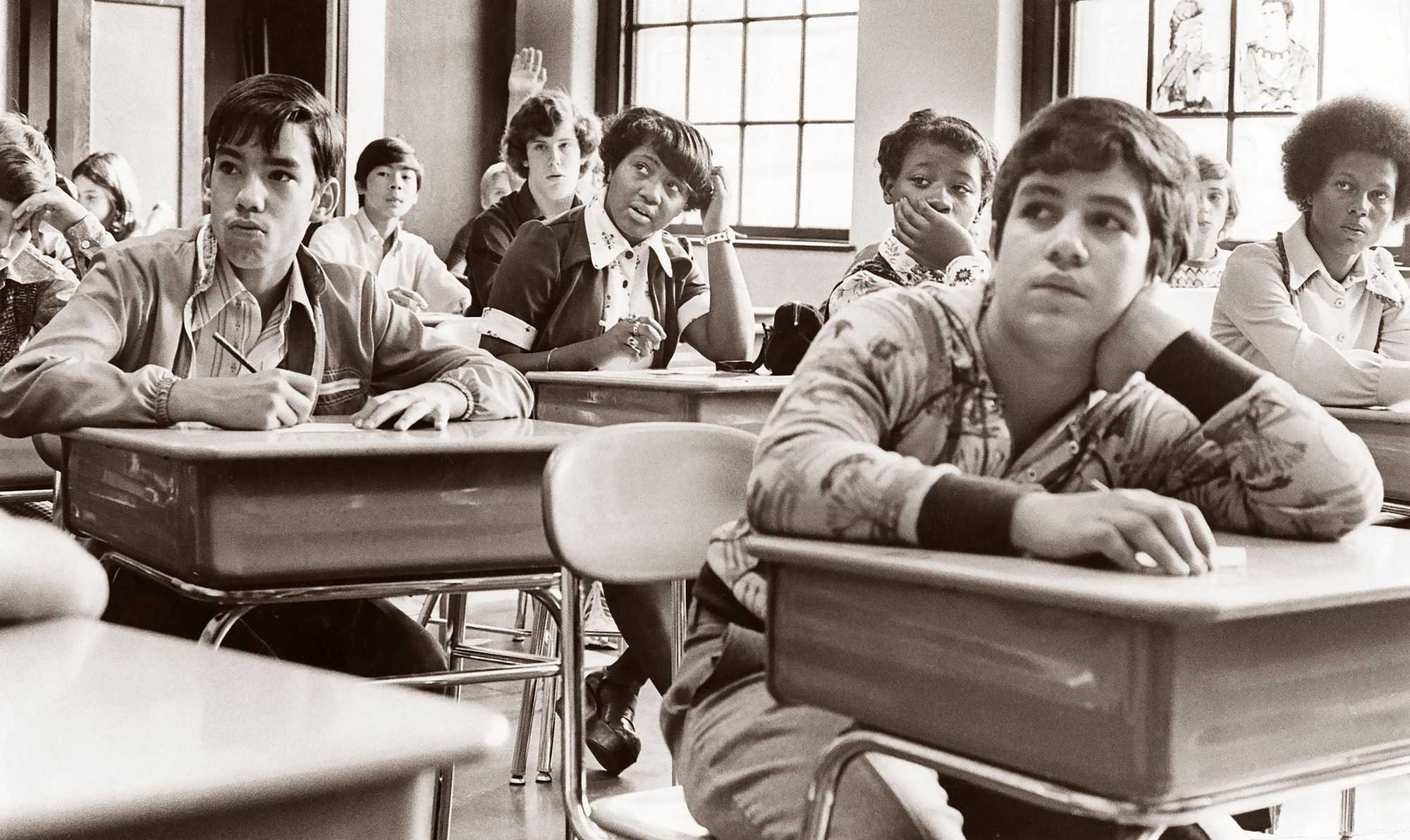

Court-ordered school integration a half-century ago was supposed to be Boston’s great equalizer. But even after decades of city and state officials pouring money into the public schools, those dollars often yield little in return, with students still struggling to find their paths to higher education, living-wage jobs, and wealth-building.

Many of those students then become BPS parents themselves, their time and resources stretched precariously thin as they attempt to make ends meet in one of the country’s most expensive cities.

Advocates argue two-generation investment is not just a matter of fixing schools or helping kids — it’s about justice. While 75 percent of white Boston residents have a bachelor’s degree or higher, less than 30 percent of Black or Latino residents do. As Boston this month marks 50 years since court-ordered busing, they say the city owes students who languished in failing schools some meaningful recompense for the educational damage done, and the economic consequences they — and their children — have suffered.

Boston's education by neighborhood

Select an education level:

Advertisement

Some nonprofits in Boston already do 2-Gen work, helping parents attain college degrees while providing their children tutoring or mentorship. But a broad two-generation approach in the city is badly needed, advocates said. Supporting parents’ education, research shows, boosts children’s aspirations for their own futures and drastically improves parents’ earnings, which are the greatest predictor of a child’s academic achievement.

“We have to think about the harm that we’ve done in the past,” said Bettina Love, a professor at Columbia University in New York who has written extensively about the concept of educational reparations. “And how do we try to repair that?”

In Texas, Osuna said she wants to show her children “you can achieve more, even if everybody else has said you couldn’t.”

The daughter of a teenage mother, Osuna grew up in a Southern California city plagued by gang violence and where poor and Latino students like her trailed their peers academically. She was homeless by her senior year of high school, and just a few days after graduation, at 17, she gave birth to Maliah. At 19, she lost the girls’ father in a tragic accident while she was seven months pregnant with Jae.

No one ever told Osuna college was for her. But after moving to Austin in 2018, she summoned the courage to try, desperately wanting to give her girls more opportunities than she’d had. She faced difficult odds: Though students who are also parents tend to have higher GPAs, their rates for completing degree programs are much lower than their classmates without kids at home.

Between classes, her job as a dental assistant, and the additional hours she spent delivering groceries to pay the bills, her daughters felt her absence. Maliah soon struggled in kindergarten, unable to sound out simple words. Osuna, feeling like a failure as a mom, ended many nights in tears.

Then she discovered Austin Community College’s Parenting Student Project. The program, supported by the United Way of Greater Austin, has allowed Osuna to maintain her studies. With the extra cash, she was able to ditch her job delivering groceries.

Jae MacDuffee, 5, leaned on her mother, Selena Osuna, as she worked on an essay for her Texas State University social work program at her apartment in Hutto, Texas. (Tamir Kalifa for The Boston Globe)

Participants in the program earn more credits, attain higher GPAs, and graduate at higher rates than the average student, said Steve Christopher, an associate vice president for Austin Community College, adding that it also sets an example for their children.

“The better version I am of myself, the more likely my children are going to feel those effects,” Christopher said.

The $500 monthly stipend, which maxes out at $6,000, covers Osuna’s car payment, affording her reliable transportation for getting to work and shuttling the girls to and from school.

Osuna, who has her sights set on a master’s degree in social work, hopes to one day provide counsel and support to families like hers, connecting them to life-changing programs.

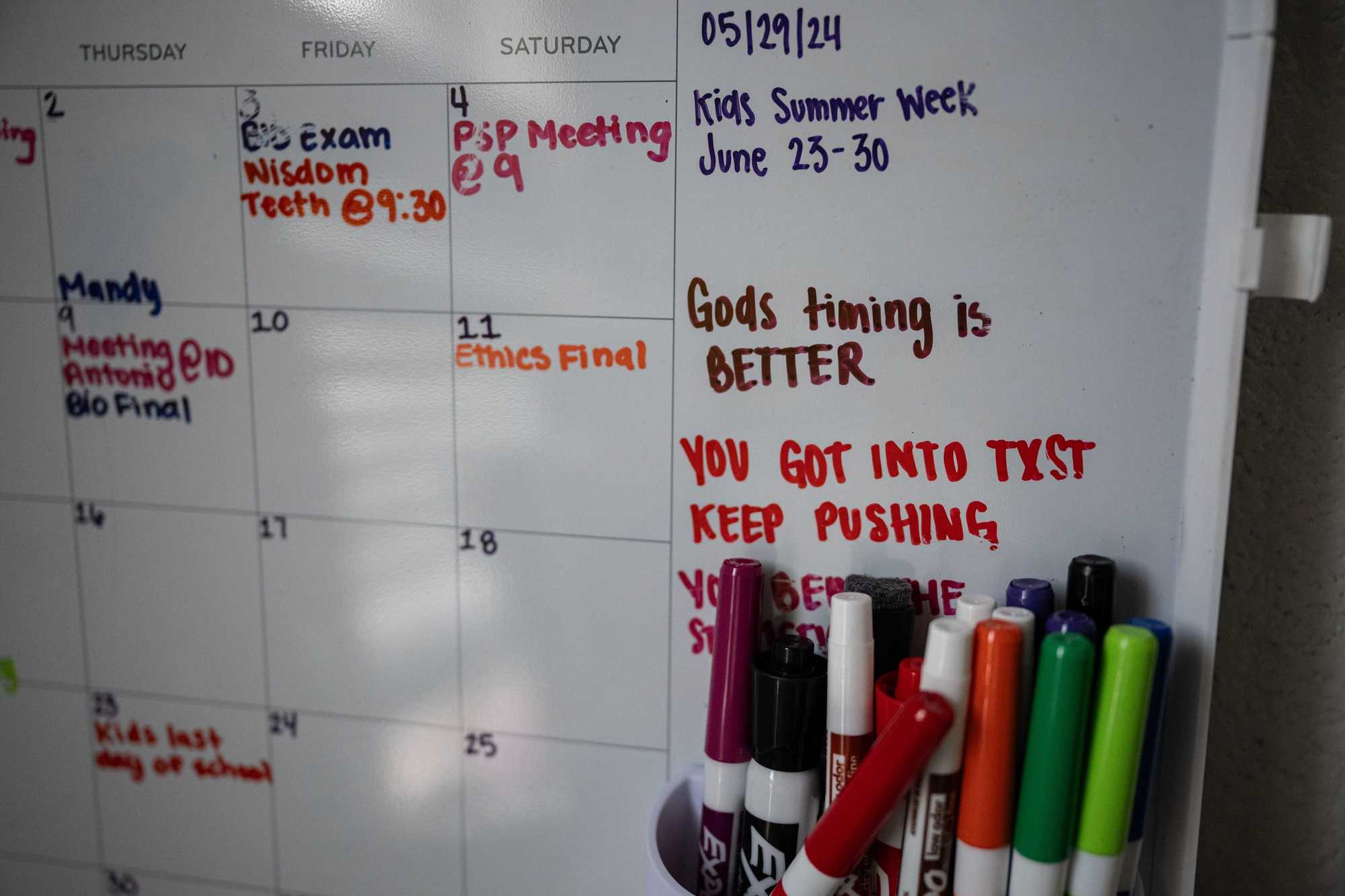

While the girls are at school, Osuna studies at the public library or in her bedroom, where a dry erase calendar details her busy schedule of classwork and mothering. Also, her determination: “YOU GOT INTO TXST, KEEP PUSHING,” she’s written, referring to her recent acceptance to Texas State University.

The changes in her life are already creating opportunities for Osuna’s daughters, who are excelling at school, in every dimension.

“Having more time for your kids and not feeling so much stress means you can be a better parent,” she said. “You can be more aware of what’s going on with your child.”

Advertisement

Two-generation programs are rooted in Indigenous communities’ holistic approach to family care, which focuses not only on physical and academic necessities, but also emotional, spiritual, and mental health needs. They have become more mainstream in recent decades, with a handful of other cities also prioritizing 2-Gen work, including Cincinnati, Atlanta, and San Francisco. In Minnesota, the 2-Gen approach is a state-level priority, with $17 million in state and federal funding earmarked for community-based initiatives.

Robyn Shahid-Bellot, dean of students for Roxbury Community College, said a 2-Gen program would be a “huge game-changer” for students at the majority-Black school. Though the college connects its students who are parents with community resources, it doesn’t directly provide child care scholarships or monthly stipends.

Recent state and city initiatives are making college more affordable, and low-income Boston parents can now send their 3-year-olds to public preschool for free. Still, the high cost of living in Boston — where median rent for a one bedroom is nearly $2,500 — can derail higher ed ambitions, Shahid-Bellot said.

Too often parents are struggling to make a living wage, said Alison Carter Marlow, executive director for the Jeremiah Program Boston, a 2-Gen nonprofit that uses individualized coaching to support mothers in earning college degrees.

“What I want to do is resource the parents so they can do for their kids what any of us would want to do for their families,” Marlow said. “We want the parent to be the hero.”

For Soneia Bowens, of the South End, having five kids at four different BPS schools makes the prospect of going back to school herself feel like a far-off dream. Parenting became a full-time job for Bowens, a former home health aide, after one of her son’s schools constantly called her to pick up the boy, who has special needs, well before the school day was over.

“I have to be on deck at all times and be accessible to them, being the only parent that they have,” Bowens said.

Bowens, who grew up in Roxbury, attended the beleaguered Charlestown High School, once the site of raucous antibusing demonstrations, in the 1990s. She never earned her high school diploma. After becoming pregnant her senior year, she started missing school.

“I was so close to graduating,” she said. “If (teachers) would have reached out more, I think that would have probably pulled me to the finish line.”

Bowens, who would be interested in a 2-Gen program like the one in Austin if offered here, wants a different outcome for her kids. Sometimes it seems to her, however, that the school system hasn’t changed since she was a student. During one meeting at her oldest son’s school, a staff member turned to the boy, 17, and told him he was old enough to drop out of school.

“I said, ‘No, as long as he’s in my house, he’s going to go to school,’” Bowens recalled. “Why would you even give him that notion?”

Yi-Chin Chen, executive director of Friends of the Children - Boston, has heard many stories from parents feeling let down by the school system. Her two-generation nonprofit employs mentors that support BPS students and their parents from first through 12th grade. But like Boston’s other 2-Gen programs, its reach is limited: For every child the nonprofit selects, there are eight more it doesn’t have the capacity to take, Chen said.

Marie Smith, senior director of programs for the nonprofit, said parents such as Bowens are owed something more by the city. Smith’s own mother dropped out of high school because of trauma she endured during busing.

“Anytime harm is inflicted on someone, there needs to be some type of reconciliation — something you walk away with, that feels like it has value. That what was owed to you is given,” Smith said. “Many people were robbed of that.”

Back in Texas, Osuna’s girls hope one day their mom is going to get a new job, one that will help them get a bigger place to live, even their own bedrooms. They envision their own possible careers: Maliah, the animal lover, a scientist, and Jae, the caretaker, a teacher.

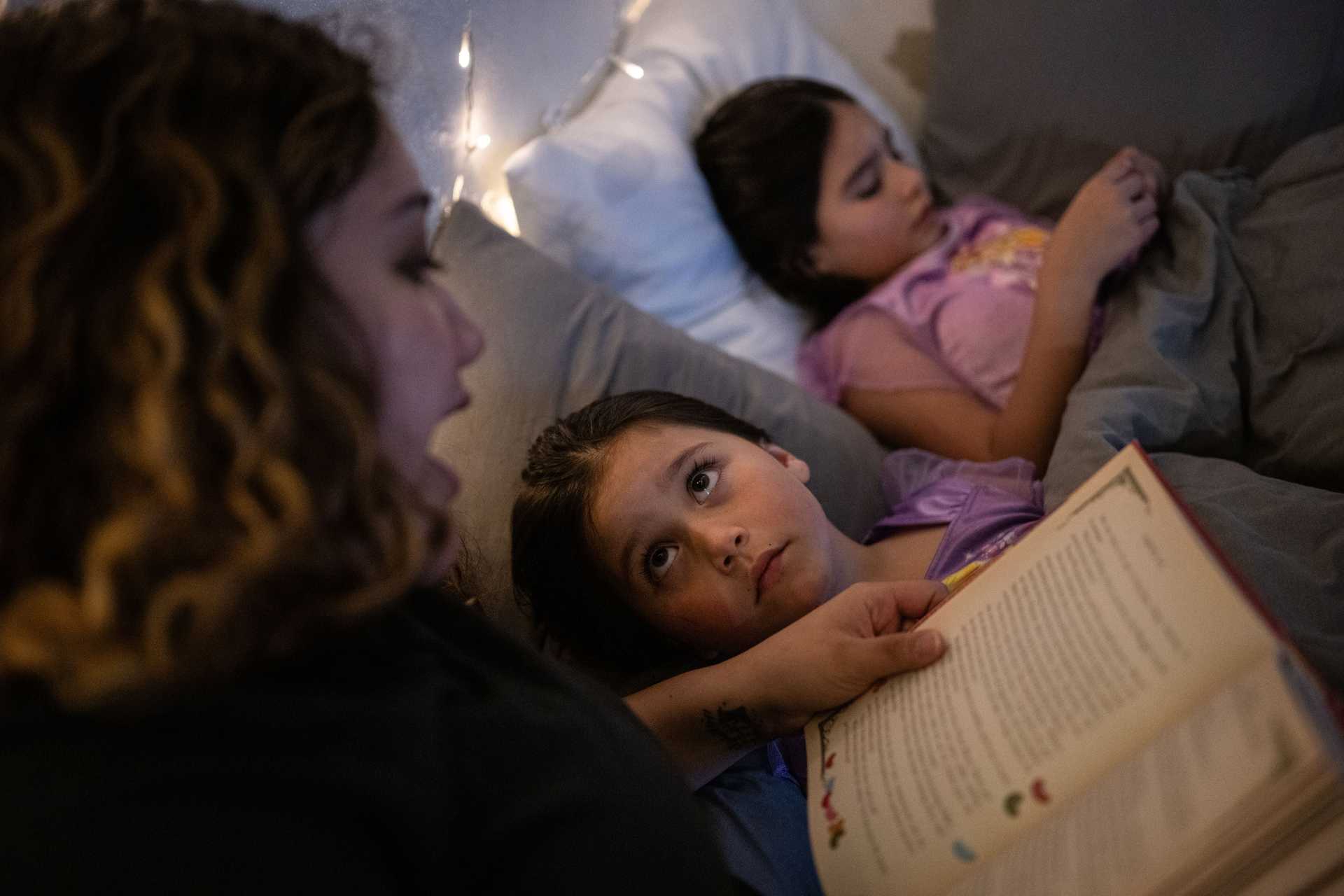

Preparing for bedtime one recent evening, Osuna combed the tangles from each girl’s freshly showered hair as the washing machine grunted. The dinner dishes waited as the three then piled onto Osuna’s king-sized bed for another round of “Harry Potter.” Maliah, who likes to do funny voices as she reads, erupted into a fit of giggles, as Jae rested her head on Osuna’s lap.

Bedtime was coming. Tomorrow, all three had school.

This story is part of a series produced by the Boston Globe’s Great Divide and Money, Power, Inequality teams. The Great Divide team explores educational inequality in Boston and statewide; Money, Power, Inequality covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporters: Mike Damiano, Christopher Huffaker, Mandy McLaren, Deanna Pan, Ivy Scott, Milton Valencia, Tiana Woodard

- Contributors: Niki Griswold, Lisa Wangsness, Marcela García, Adrian Walker

- Editors: Melissa Barragán Taboada, Kris Hooks

- Additional editors: Anica Butler, Cristina Silva, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Suzanne Kreiter, Jessica Rinaldi, Lane Turner, Craig F. Walker, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of Photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Video producers: Randy Vazquez, Olivia Yarvis

- Audio producers: Jesse Remedios, Scott Helman

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editors: Michael J. Bailey, Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Jenna Reyes, Adria Watson

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer, Adria Watson

- Homepage strategy: Peter Bailey-Wells

- Project lead: Melissa Barragán Taboada

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC