BROKEN PROMISES, UNFULFILLED HOPE

50 years after busing decision, a school system still unequal, still segregated

Busing was set in motion by rightfully furious Black parents making modest demands: equal educational opportunity for their children and good schools in their own neighborhoods. It never happened.

Emmanuel Vargas stepped out of his ground-floor Hyde Park apartment and into the morning darkness. He checked the time on his phone: 6:19. He was running behind. He pulled his hood over his head as a shield from the pouring rain and speed walked to the bus stop.

When the number 40 bus pulled up a few minutes later, Vargas joined a dozen other passengers for the 21-minute stop-and-go ride up Washington Street to the Forest Hills Station. There, he caught the Orange Line to Ruggles, then the 15 bus through Roxbury to Dudley Street, before walking the last leg of his commute to school. After traveling for nearly an hour and a half, Vargas walked into homeroom at 7:40. He was 10 minutes late.

“It is what it is,” he said.

Vargas makes this nearly three-hour round trip every school day to attend the Dearborn STEM Academy, a college-focused high school with computer labs and 3-D printers. He thinks it will give him the best shot at becoming the first in his family to graduate from college and propel him to a lucrative career in computer engineering.

His draining commute is nothing out of the ordinary for a student in Boston Public Schools, a district that tests how far students will go to get the education they deserve. Fifty years after a federal court forced Boston to desegregate its schools with busing, and 36 years after that order was lifted — returning full responsibility to the city — tens of thousands of children and teenagers still crisscross Boston every school day.

Nearly a third who take the district’s school buses — more than 5,500 out of roughly 18,000 — ride more than two miles from their home or a bus stop. Others, like Vargas, commute on the MBTA. About 10,000 more travel to charter schools. Nearly 3,000 more leave the city altogether, on buses that take them to schools in the surrounding suburbs.

This is the legacy busing left behind: a school system so rife with inequities that students trek across the city and beyond in search of a quality school matched to their needs.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Court-ordered busing was meant to integrate the district. The Black families who filed the federal suit that led to the order hoped that integration would lead to better schools and fairer outcomes for their children. But nothing like that happened back then. And it still hasn’t today. Boston, after regaining control of its schools in 1988, tried to correct course, to break free from the legacy of busing and build something better in its place.

But the city never mustered the will to get that done. Instead, Boston’s public schools remain intensely segregated and the academic outcomes of the students they serve are staggeringly unequal. Boston’s children, especially its most disadvantaged, bear the consequences of that history of failure. It is the biggest broken promise in the city’s modern history.

Today, the district’s schools produce among the worst academic outcomes in the state, according to standardized tests measuring proficiency in English and math. And those abysmal district-wide results hide stark inequities among racial groups and between students from low-income families and from wealthy ones. Only 14 percent of Black BPS students test at grade-level proficiency in math, compared with 59 percent of their white classmates. In recent years, about half of Black students have gone on to college, while three-quarters of white students have.

Boston schools have certainly improved in some ways since court-ordered busing; graduation rates are up and dropout rates are down. But busing had little to do with the long-term gains, according to an analysis by Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers requested by the Globe. And the troubles plaguing BPS are much the same as they were 50 years ago: It remains a system divided by race and privilege, one that provides a robust education to some and a lackluster one to many more.

How did it come to this?

Advertisement

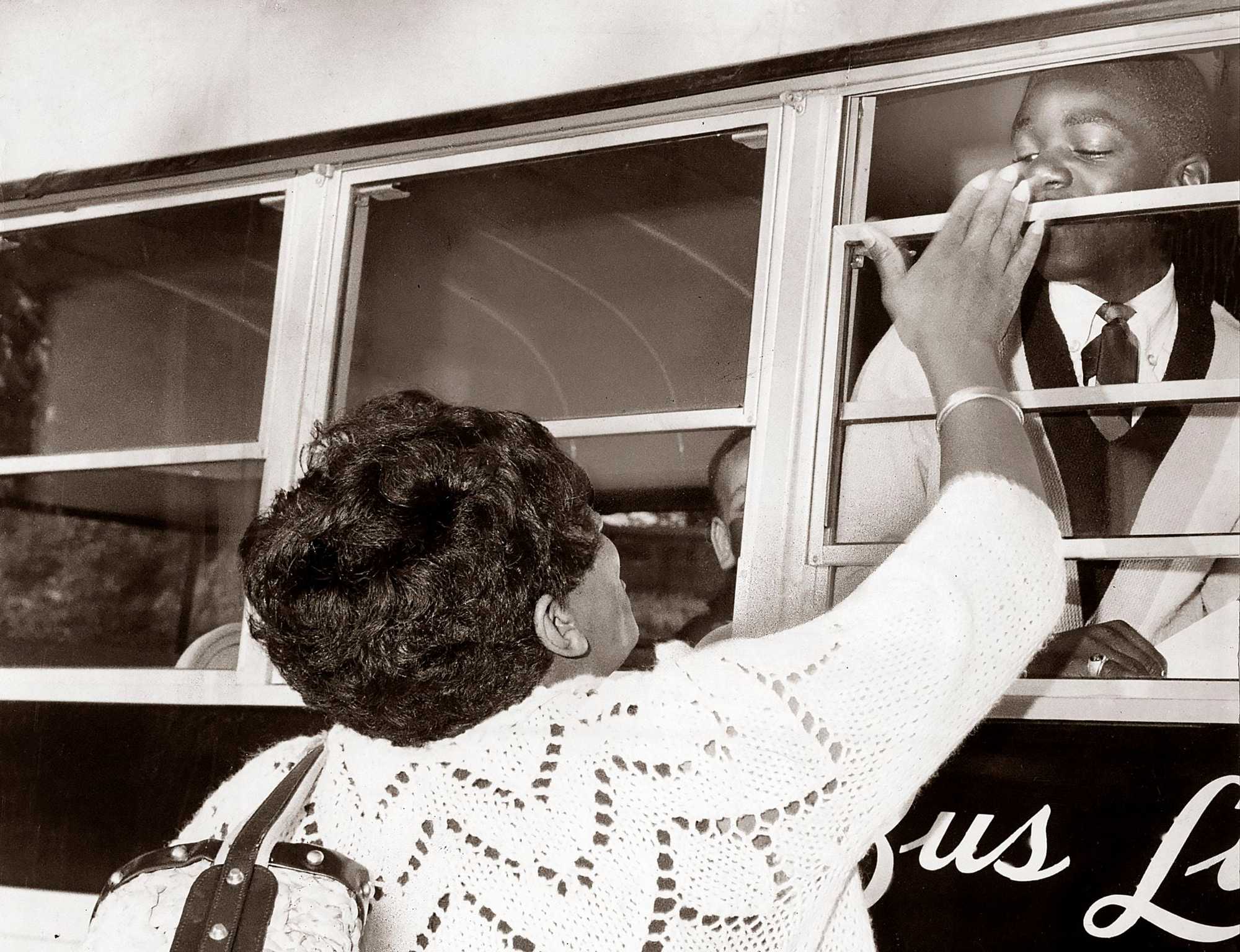

Busing was set in motion by rightfully furious Black parents making modest demands: equal educational opportunity for their children and good schools in their own neighborhoods. It was a movement that began in the early 1960s and culminated, a decade later, with a federal lawsuit brought by 14 Black families backed by the NAACP. They alleged Boston ran a deliberately discriminatory and segregated school system that illegally disadvantaged Black children.

US District Judge W. Arthur Garrity, Jr. agreed, finding on June 21, 1974, that the Boston School Committee ran a “dual system” — separate and unequal — that must be dismantled “root and branch.” His mandated remedy was busing, and when the new school year began, 18,000 students, Black and white, would be boarded onto yellow buses and taken to new schools in parts of the city many barely knew.

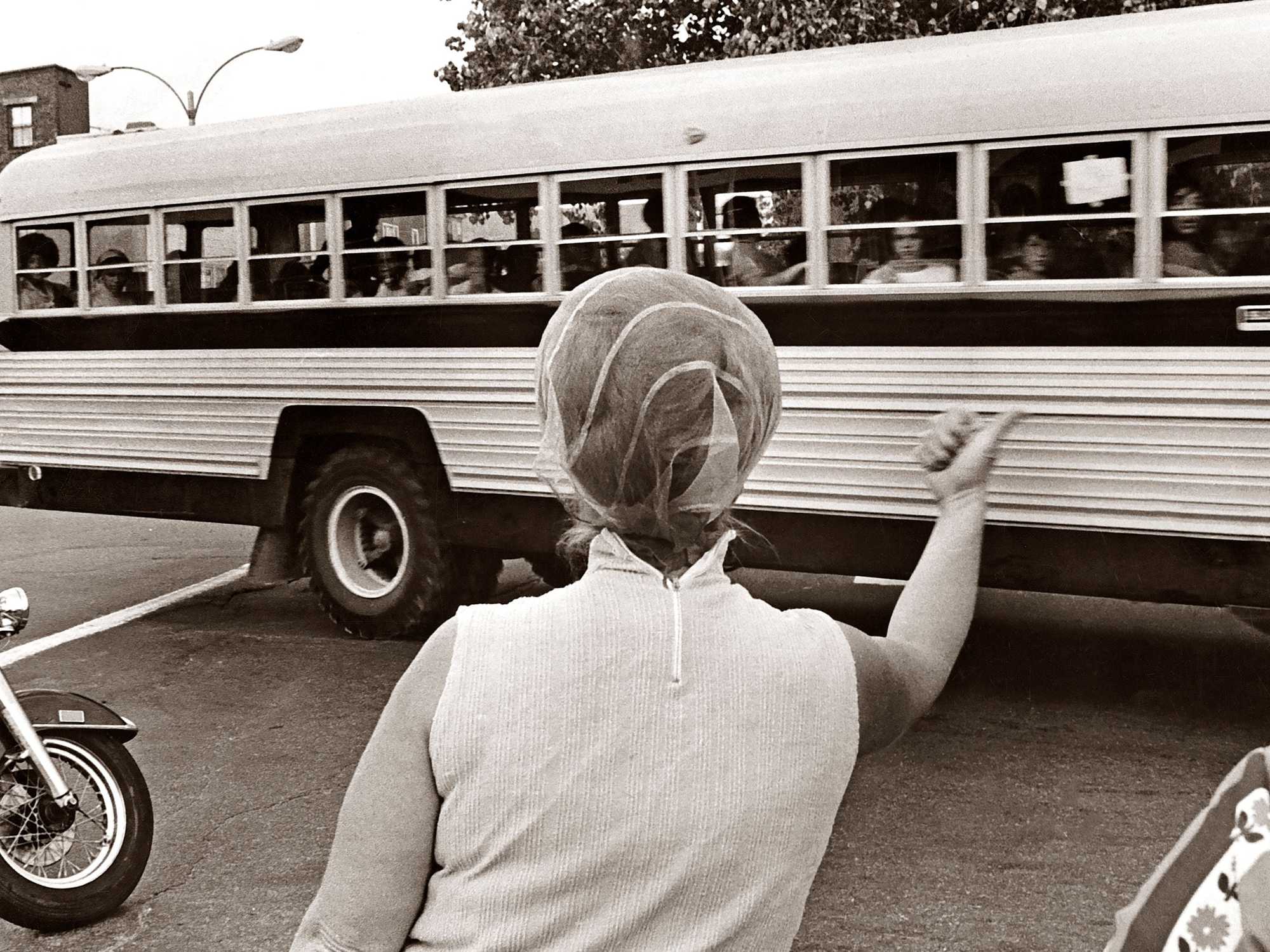

Garrity’s order tore the city apart. White mobs threw rocks at buses carrying Black children. Students fought in hallways. Hundreds were arrested during protests and clashes. One school was shut down for a month after a student was stabbed.

A woman gestured for students being bused home to Roxbury to, "Go home and stay home," as a school bus leaves Patrick F. Gavin Middle School in South Boston on Sept. 17, 1974. At right, police arrested a man during a pro-busing rally on Boylston Street in Boston on Dec. 14, 1974. (Charles Dixon, George Rizer/Globe Staff)

Many families, both Black and white, said busing had only made their education, and their lives, worse. Thousands of white families fled for the suburbs. Other Bostonians marched in favor of busing. As disruptive as Garrity’s remedy was, they saw it as the only way to secure an equal education for all.

Forced busing continued for 14 school years until a federal appeals court lifted Garrity’s order in 1987. By then, the district was still far from integrated: So many white families had left Boston that the district, once majority-white, was now 48 percent Black and 19 percent Latino. But the appeals court ruled Boston had done all it could “in good faith” to integrate its schools. Control of the district, and the convoys of buses it relied on, went back to the city.

The return of local control ushered in a period of soaring promises from political leaders, followed by repeated failures to follow through on them.

Then-mayor Raymond Flynn called the end of court-ordered busing a “historic opportunity” to restore “confidence in public education.”

He said Boston would continue busing, but now student transportation would serve to give families more options. He cut the city into three school zones, and families generally chose schools within the zone where they lived. The system, known as school choice, would be temporary, merely a bridge to a better day, when there would be high-quality schools in every neighborhood. But that never happened. Schools in majority Black and Latino neighborhoods continued to flounder, so busing rolled on.

Boston’s next mayor, Thomas Menino, had had enough. The city needed to stop pouring “dollar after dollar into gas tanks,” he said. Flynn’s school choice system, he said, tore at the fabric of local communities. He vowed to build a network of neighborhood schools that would provide all Boston families good educational options close to home. That would have led to less busing. Menino planned to close existing schools to transfer students to the new ones closer to their homes. But the plan stalled in the face of parent opposition. After decades of broken promises, parents didn’t trust the district to do what it had never done before: provide good schooling in majority Black and Latino neighborhoods.

Menino’s plan to roll back busing collapsed. In 2012, he settled on a revamped school choice system instead. Boston, it appeared, could not provide high-quality schools in every neighborhood. Instead, it created a ranking system. The best schools, defined largely by standardized test scores, were placed in Tier 1, the worst in Tier 4. Every student would have the option to attend a high-ranking school no matter how far it was from home. The idea was that even if Black and Latino students had to travel long distances, at least they would have equal access to the district’s best schools.

It didn’t work. In 2018, an analysis the city commissioned by researchers from Harvard and Northeastern found Menino’s system failed to increase access to high-quality schools for Black and Latino students because there were too few good ones. The researchers suggested some tweaks to the system that would improve it. But overall, what the analysis implied was bracing: BPS couldn’t bus its way out of its problems.

Today, nearly two-thirds of the Tier 3 and Tier 4 schools are in majority Black and Latino neighborhoods. The Tier 1 and Tier 2 schools tend to be located in whiter and more Asian parts of the city. And there simply aren’t enough of them.

School choice is merely “a game of musical chairs,” said Paul Reville, a former Massachusetts secretary of education. Too many students are shuttled from one neighborhood where they could get an inadequate education to another where they get the same.

Boston Public School finder

Explore the schools of the Boston Public School system. Click on the map or select from the dropdown menu.

Neighborhood:

Grade level:

Total number of students:

Tier school choice:

Per pupil spending:

Student/teacher ratio:

Overall building score:

Experienced teachers:

Unique language, art, and AP classes:

Student demographics:

If there was any doubt remaining about whether busing to distant Boston public schools improves academic results, it was put to rest two years ago. That’s when a team of education researchers at MIT published a landmark study of the school choice system.

They compared the academic outcomes of two categories of students: students who used the school choice system to attend distant schools and students who applied to attend the same schools, but didn’t get assigned to them. Their conclusion: School choice led to somewhat more integration, but it produced zero academic benefit — no boost in test scores or in college enrollment.

This year, at the Globe’s request, the same team analyzed outcomes at several big city districts from the era of court-ordered busing and found minimal evidence of lasting academic benefit. The research makes it clear that Boston Public Schools has improved significantly by some measures in the past 50 years — dropout rates are down, graduation rates are up. Busing, they found, may have helped somewhat in its early years, but other districts had similar results, suggesting busing deserves little credit for the long-term gains.

From an educational standpoint, the money, energy, and heartache poured into busing had mostly been a waste.

Today, Mayor Michelle Wu has her own $2 billion plan to revamp Boston schools. It involves closing dozens of them. But those plans seemingly stalled last month when the district announced that instead of closing a handful of schools after the next school year, it would close just one. (There are four mergers underway.) In an interview, Wu said her administration remained committed to carrying out her plan. But she urged patience.

Before closing any school, she said, the district had to be certain there were enough “high-quality seats” available elsewhere for every displaced student. Right now, there aren’t.

There it was again, that old and painfully familiar problem, the one that has stymied progress for all these years. What might change now?

“We have to do things right when there’s been a history of not getting it right, over so many decades,” she said.

Advertisement

Kueen King, a mother of two boys, owns a home and a hair salon in Dorchester. She loves her neighborhood. Her friends, her family, and her church are nearby. There is also a public school down the street, the Joseph Lee K-8 School. Her sons could walk there.

But she has heard bad things about the Lee from her neighbors, and she simply doesn’t trust BPS to educate her boys. Her concerns are well-founded. Only 2 percent of students at the Lee demonstrate grade-level proficiency in math.

So instead of sending them to school nearby, she wakes them up before 6 a.m. every school day and drives them to Newton, where she has enrolled them in that city’s public schools through Metco, the voluntary integration program that was born amidst the civil rights struggles of the ‘60s. “It isn’t as convenient, but I know I am getting what I need as a parent and they are getting what they need,” she said.

Tavaj King put on his backpack while his mother, Kueen, wiped the face of his brother, Tairih. At right, Kueen King hugged Tavaj after dropping him off at a Newton public school. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

Stories like King’s are common among Boston families. Aware of the district’s shortcomings, parents scramble to find adequate schooling for their children. For some, that means an all-consuming focus on getting their children into one of the district’s three selective “exam” high schools. For others, it means securing one of the limited spots in Boston’s charter schools. Or pursuing opportunities, often through Metco, outside Boston.

Parents have good reason to seek out these alternatives. Boston’s exam schools rival elite, private high schools. The top-performing charter schools have, in the recent past, matched the performance of suburban schools in standardized test scores and attendance (although they have struggled to recover from pandemic-era setbacks).

Metco, meanwhile, has produced academic results that are superior to BPS. A recent study by Elizabeth Setren, an economist at Tufts University, found that students enrolled in Metco scored better on standardized tests, missed school less, and were more likely to graduate on time than students who were on the Metco waitlist.

It’s a sad state of affairs. The “dual system” Black parents sought to dismantle 50 years ago has survived.

The exam schools and the district’s most sought after Tier 1 schools disproportionately serve white, Asian, and wealthy students. Their students outperform state averages on standardized tests. Attendance rates are comparable to those of suburban schools. Almost everyone graduates.

Meanwhile, schools with mostly Black and Latino student bodies — that is, the vast majority of the district’s schools — are older and in worse condition. They have broken generators, failed HVAC systems, cracked sidewalks and floors. Their teachers are less experienced, and turnover is high. They offer less: fewer languages and Advanced Placement classes, less art, and not as many sports teams.

They do not get equal academic results, either. On the state’s standardized tests, Black and Latino BPS students meet grade-level expectations at much lower rates than their white and Asian classmates. And the disparities begin as early as elementary school. Only 12 percent of Black third through eighth graders and 14 percent of their Latino peers meet grade-level expectations in math. That compares to 57 percent of white students and 63 percent of Asian students.

For Robert Lewis, an East Boston native who is now the president of the Boys & Girls Clubs of Boston, these outcomes are a catastrophe for Boston’s Black and Latino communities, and for the city at large. “We’ve got to educate our kids. We’ve got to get them ready for [leadership] positions, for jobs and opportunities,” said Lewis, who attended East Boston High School during the busing crisis. “We need our folks to be able to participate and compete in this 21st century economy.”

The stakes are existential. Boston must adequately educate all its children, he said, “So we’re not losing these Black and brown kids who grew up and were raised in our communities.” The white flight of the 1970s is now replaying in different form as a kind of Black exodus in the 21st century. The district has 15,000 fewer Black students than it did 20 years ago.

Funding isn’t the problem. Boston spends more per student (about $35,000 per year) than every big-city school district except New York. And it spends more on its Black and Latino students than their white and Asian peers.

Boston Latin School, the district’s flagship institution, spends approximately $24,000 per student every year, significantly less than the district average. At the Joseph Lee School — where King refuses to send her sons — per-student spending is more than $35,000.

But in Boston’s broken school system, money is only part of the story. The district serves a high-needs student body. Seventy percent of its students come from low-income families. More than a third are learning English as a second language. Almost a quarter have diagnosed disabilities. Hundreds are recent immigrants, who often reach Boston with little, if any, formal schooling. It costs more to educate students who face these disadvantages.

In-demand schools serving predominantly white and Asian students have a structural advantage, as well. They are bigger. All of the exam schools serve more than 1,500 students. That makes them more efficient and enables them to offer far more classes and programs.

The rest of the district’s high schools tend to be smaller, in large part because they are in lower demand in the school choice system. Under-enrollment drives up costs and makes it impossible to offer a wide range of classes and programs. There simply aren’t enough students to fill them.

There’s a vicious cycle at play. The worse a school’s reputation, the fewer students it attracts, and the harder it becomes to offer the students who do show up an experience to match what students at exam schools or suburban schools enjoy.

In response, parents will do what they feel they must.

“They want the best for their kids, and they are going to do anything, whether they think it’s across the street or across town, parents are going to make that sacrifice to get their kids the best,” said Kim Janey, who was bused as a BPS student and later served, for eight months, as Boston’s acting mayor. “We’ve got to do more in this city to make sure that BPS is a real option, a viable option, a strong option, the best option for families, and sadly, it isn’t.”

Advertisement

East Boston is a tantalizing example of what parents have demanded and what mayors have promised for decades: a neighborhood system where parents trust their nearby school and academic outcomes are trending upward.

Because of the neighborhood’s isolation — it’s practically an island, surrounded by a harbor, an airport, and the city of Revere — East Boston largely escaped court-ordered busing and relies less on school choice today. Neighborhood residents get priority to attend East Boston schools, and they take almost all of the seats. Phillip Brangiforte, principal at East Boston High School, estimates nearly 90 percent of his school’s students are from the neighborhood, and they choose it partly because they feel a sense of ownership of the school.

“There’s something to be said for neighborhood schools — it works,” he said after a recent concert in the school’s auditorium, which brought children from neighborhood elementary schools, many of whom will become East Boston High students. “It’s very difficult for people to have a sense of belonging [otherwise].”

East Boston High School is one of the district’s success stories. It has achieved significant gains on key academic measures. Its graduation rate has climbed from 56 percent in 2014, to 86 percent in 2023, which eclipsed the district’s average and is just a few points shy of the state’s. Last year, standardized test scores at East Boston High dipped below the district average, but it has seen sustained gains in those scores for a decade.

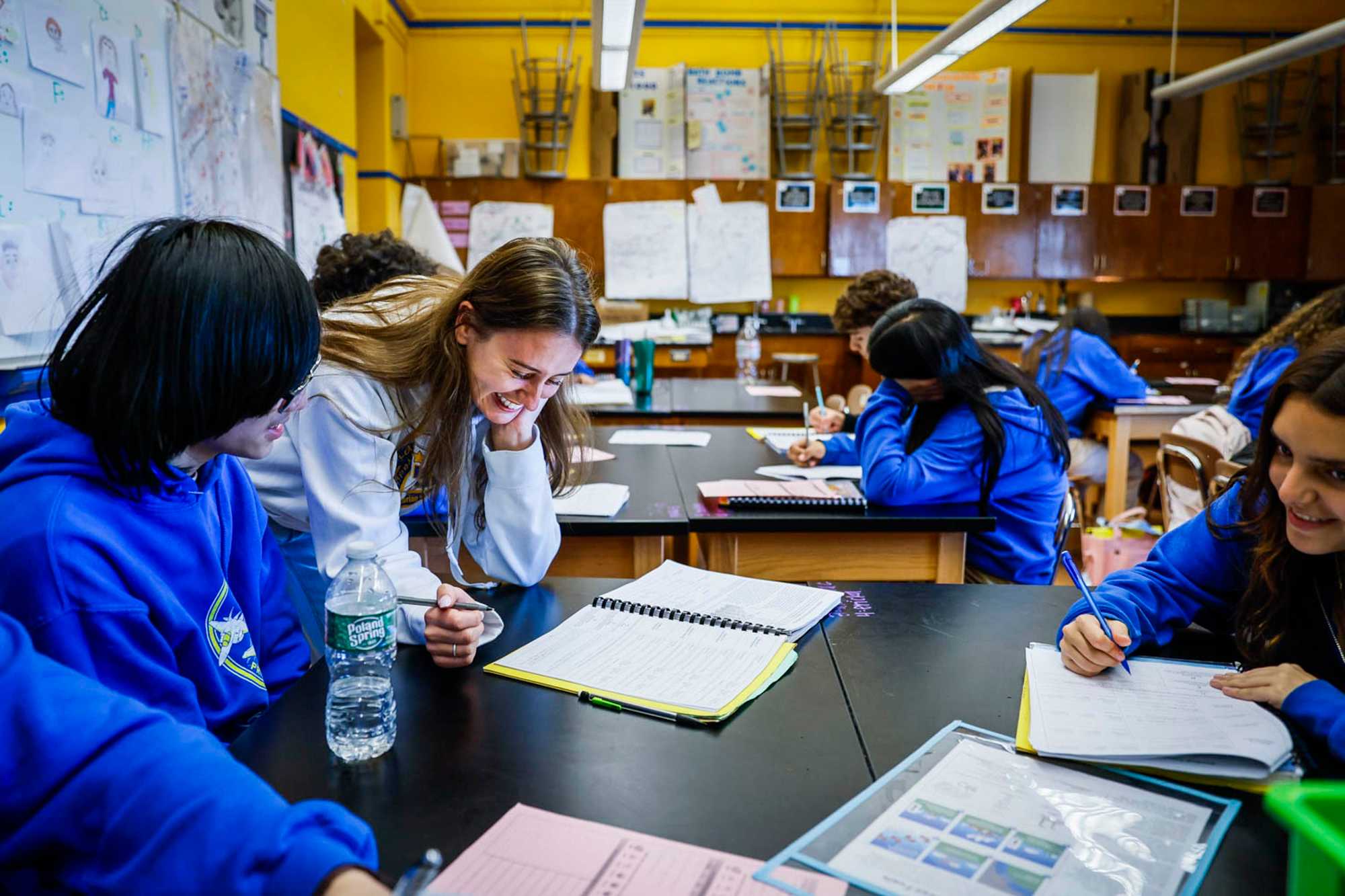

East Boston High School science teacher Molly Mus worked with her students in their classroom on May 17. In some ways, East Boston High stacks up against the exam schools with the number of offerings it has for students. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

In some ways, it even stacks up against the exam schools. It offers 13 language classes, more than 20 sports teams, music and arts programs, and an extensive program for students learning English as a second language. Because of the school’s reputation and its offerings, students clamor to go there. About 1,300 attend — 82 percent of whom are Latino — making it one of the district’s biggest. Every seat is taken.

East Boston High embodies the dream of neighborhood schooling, but also its pitfalls. In a city with intense residential segregation, sending all children to school close to their homes would mean giving up on the original goal of busing: integration.

The Black families who set busing in motion believed the city would never provide their children good schooling as long as the district remained segregated. Fifty years later, with a district that is still deeply unequal, that conviction persists.

“I think it would be wonderful if my kid could go down the street and attend the school there,” said Barbara Fields, former head of the district’s Office of Equity and a board member of the nonprofit Citizens for Public Schools. “But the tragedy of all this is we still have to go to where white kids live to get some of the benefits they have … because they won’t put it in our neighborhoods.”

Wu and the district’s superintendent, Mary Skipper, say they have no intention of abolishing school choice entirely — they will not force students to attend subpar schools. What they hope, instead, is that schools in every neighborhood will be good enough that busing as we know it would become obsolete.

It’s a familiar promise, echoing the vows of mayors who came before them. Flynn said it. Menino said it. Martin J. Walsh said it.

To get there, Skipper and Wu have said the district should close a portion of its 119 schools. Their $2 billion plan to renovate and rebuild the district called for closing dozens. Closing schools is not enough on its own to fix the district’s problems, but it is necessary, Skipper said in an interview.

So when, in May, the district announced that instead of beginning the process of closing dozens of schools, it would instead close one, many observers of the district’s troubles reacted with dismay.

It looked like one more failure, one more missed opportunity, one more delay.

Parents can’t wait. Neither can their children. So they do what they must to get the best education they can now.

A teenager bypasses a nearby school in Dorchester, fearful of its reputation for violence, to attend a charter school miles from home.

A soon-to-be ninth grader from Jackson Square agonizes over what to do if he doesn’t win admission to one of the city’s prized exam schools.

A 14-year-old from the city’s eastern edge wakes up at 6 a.m. to board a bus to high school in Brookline through Metco, because his mother doesn’t want him attending Boston schools.

To Vargas, the Dearborn Academy student who endures a nearly 90-minute commute, the ask is just too much.

“That shouldn’t be the sacrifice you have to make, just for a good education,” he said.

This article is based on publicly available data collected by MIT Blueprint Labs and The Boston Globe, and research conducted by MIT Blueprint Labs under a data use agreement with Boston Public Schools. Data was compiled by Joshua Angrist, Guthrie Gray-Lobe, Bettina Hammer, Clemence Idoux, and Parag Pathak of MIT, and Christopher Huffaker of the Globe.

This story is part of a series produced by the Boston Globe’s Great Divide and Money, Power, Inequality teams. The Great Divide team explores educational inequality in Boston and statewide; Money, Power, Inequality covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporters: Mike Damiano, Christopher Huffaker, Mandy McLaren, Deanna Pan, Ivy Scott, Milton Valencia, Tiana Woodard

- Contributors: Niki Griswold, Lisa Wangsness, Marcela García, Adrian Walker

- Editors: Melissa Barragán Taboada, Kris Hooks

- Additional editors: Anica Butler, Cristina Silva, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Suzanne Kreiter, Jessica Rinaldi, Lane Turner, Craig F. Walker, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of Photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Video producers: Randy Vazquez, Olivia Yarvis

- Audio producers: Jesse Remedios, Scott Helman

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editors: Michael J. Bailey, Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Jenna Reyes, Adria Watson

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer, Adria Watson

- Homepage strategy: Peter Bailey-Wells

- Project lead: Melissa Barragán Taboada

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC