Fifty years ago, a federal judge ordered Boston's public schools to desegregate, thrusting tens of thousands of students into the largest busing program in the city's history.

The decision threw the city into a state of chaos. White rioters threw rocks at school buses carrying Black children into white neighborhoods. Fights broke out inside schools. Students were stabbed. Actual education came to a standstill. The city felt unsafe.

BROKEN PROMISES, UNFULFILLED HOPE

This is Boston’s busing era captured through photos

From the very start of court-ordered desegregation, in September 1974, the faces of Boston’s busing era told stories.

They were stories of hope and resistance, of dreams of inclusion and deep-rooted neighborhood insularity.

Busing was the seminal event that turned Boston against itself, pitting neighborhood against neighborhood, and redefining the way America viewed the city. For years, I have referred to it as Boston’s Civil War.

South Boston and Charlestown were transformed into areas where people of color would feel physically unsafe for years to come. Meanwhile, residents of those neighborhoods would profess their resentment at being dragged into a social experiment they never signed up for. In truth, no Boston neighborhood would emerge unscathed from the turmoil of busing in the 1970s.

Many will argue, to this day, that if improving education was the goal, desegregation never achieved it.

But the way to really feel the impact of Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr.’s landmark decision isn’t through rehashing political debates. It’s by looking into the faces of Bostonians — grappling, even warring, with their new reality.

The Black children on buses in South Boston, hoping to make it to school safely for one more day. The Black and white students on a bus together, but seated apart. The people who sought, day after day in those grim years, to shut busing down, and those who persevered.

These images tell their stories.

It was the start of the biggest social experiment in Boston’s history: After more than a decade of agitation and litigation, the walls that separated Black and white schoolchildren since the 19th century were about to come down.

But no one was under any illusions that court-ordered desegregation was a popular idea, or an easy sell. White families started protesting before school even began, planning to block busing by any means necessary, including physical intimidation.

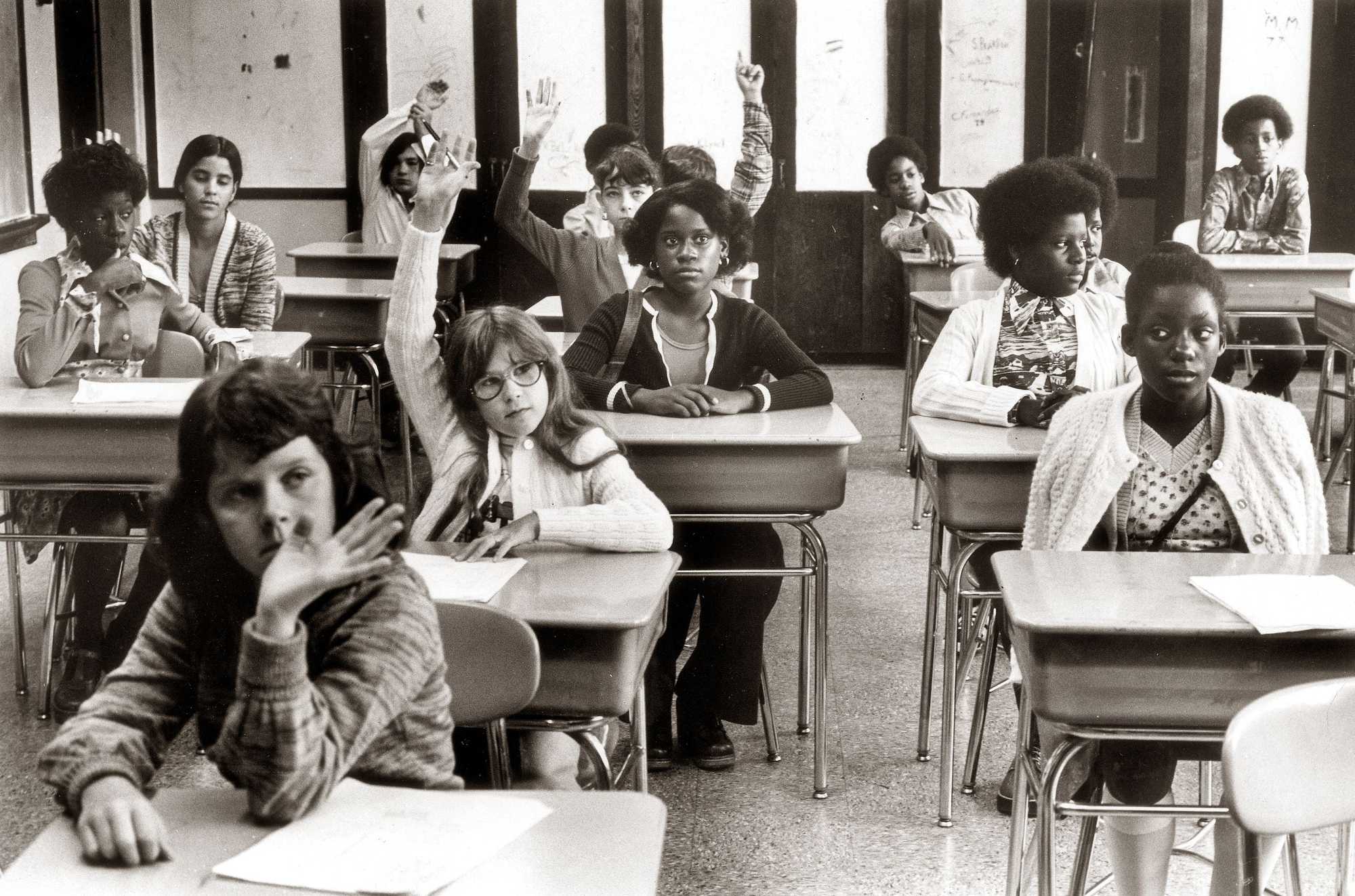

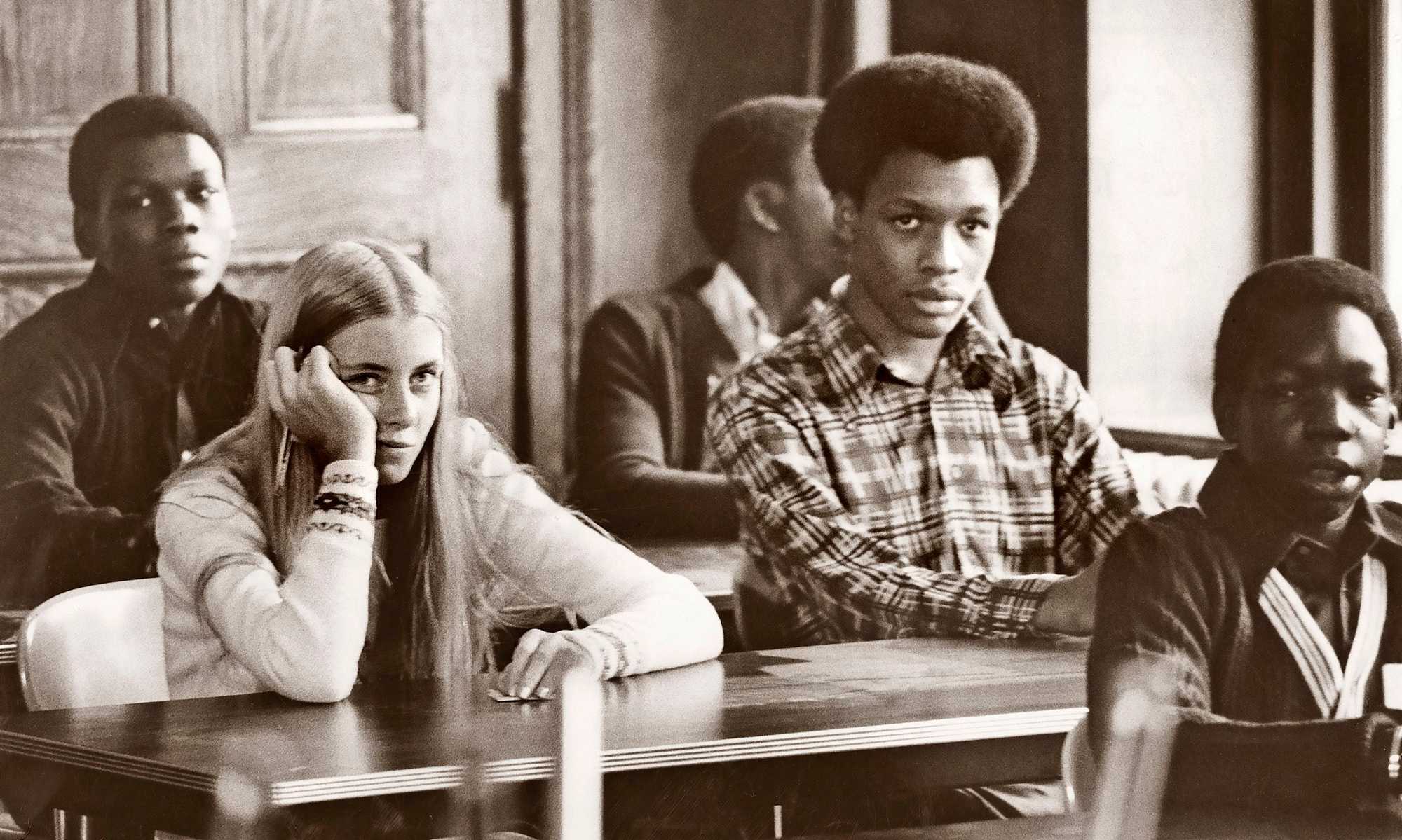

At the Curley School, the tension is written all over the faces of students — especially Black students, who were forced to be constantly on guard, and on edge.

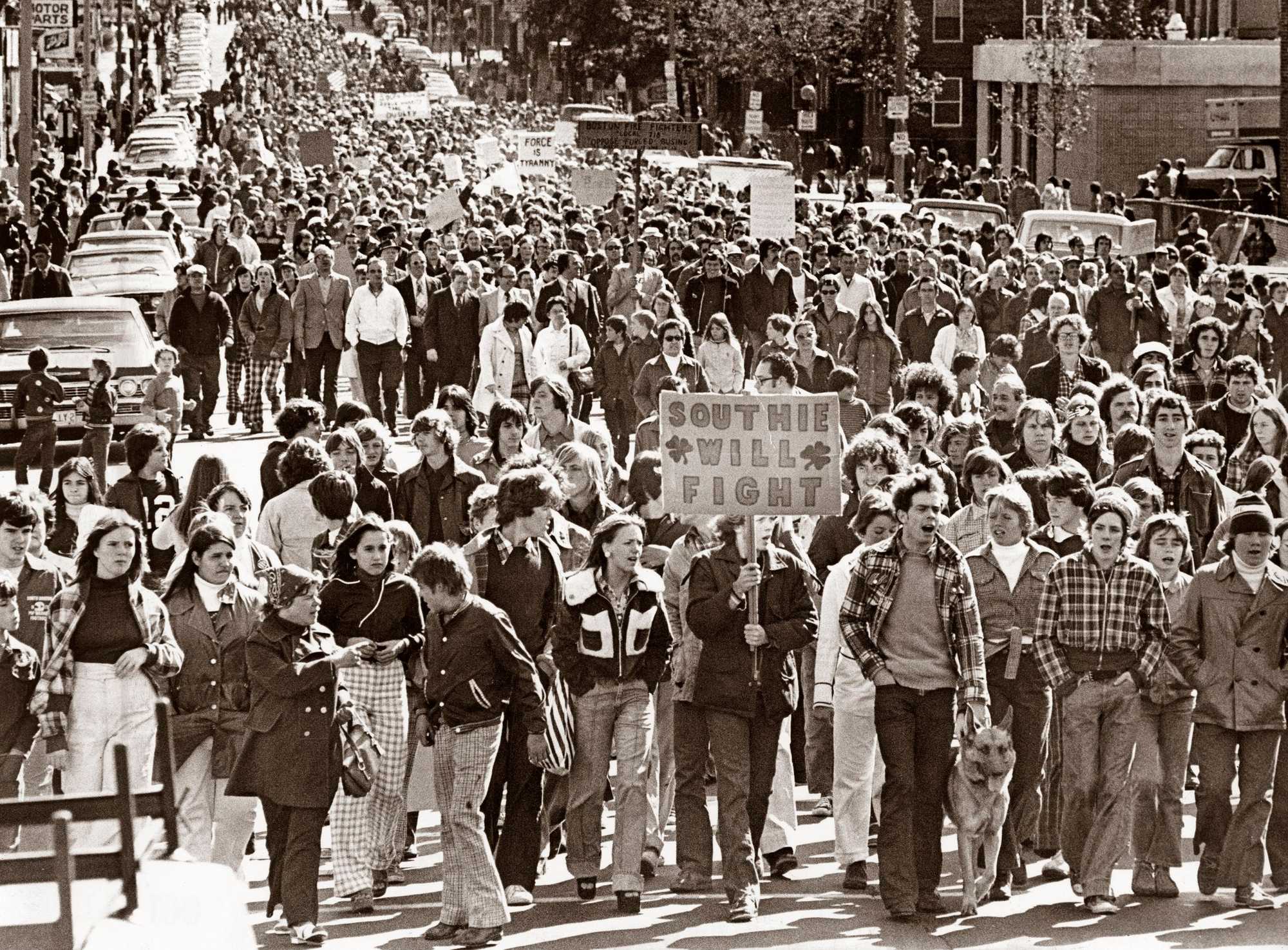

Though busing touched every Boston neighborhood, no neighborhood wore its sense of grievance and resentment on its sleeve more than South Boston. The slogan of anti-busing leader Louise Day Hicks of South Boston was “You know where I stand.” And her followers made sure to leave no doubt where they stood on busing.

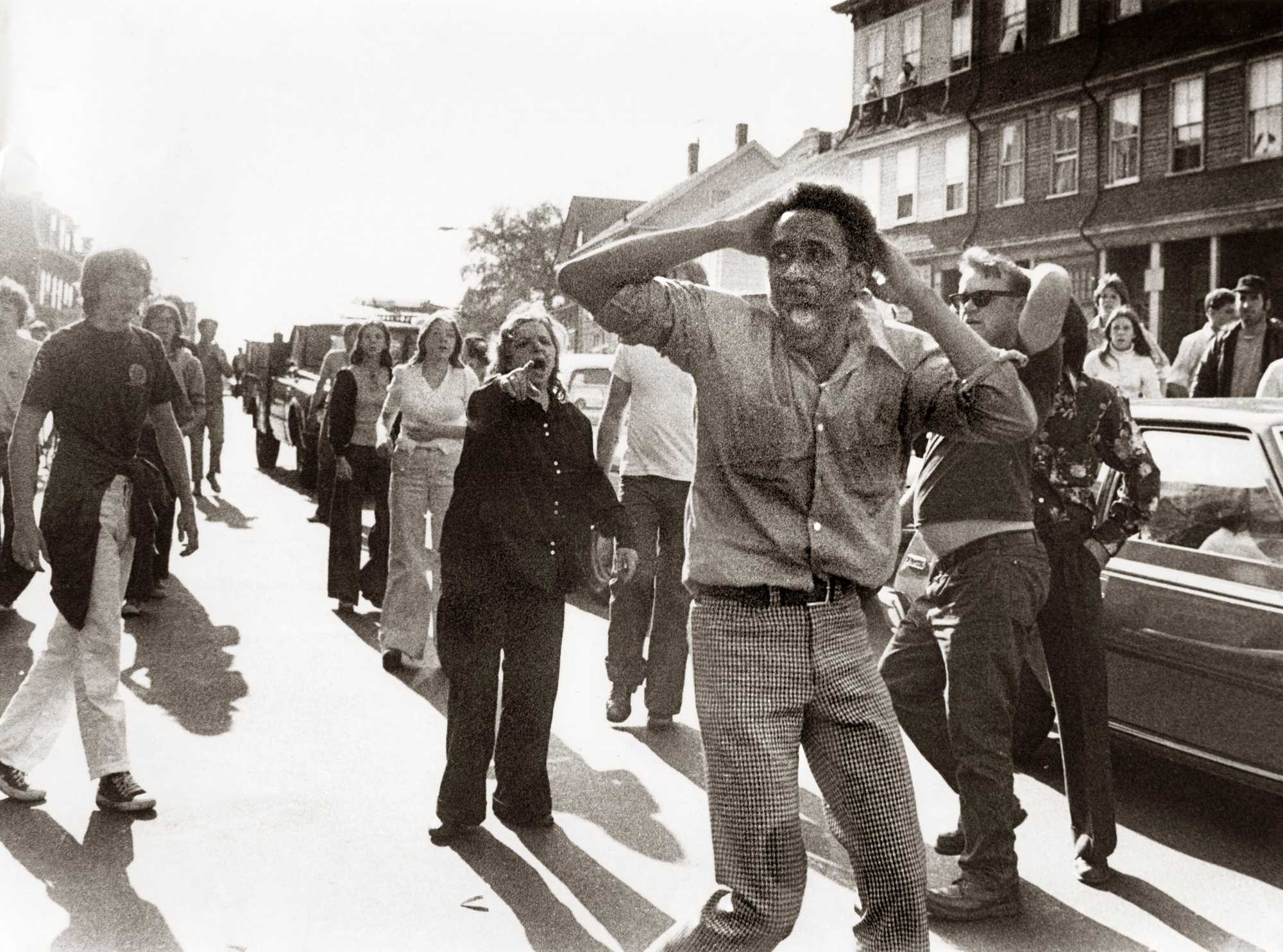

Suddenly, it was dangerous just to be a Black person in South Boston. That was true not just for students, but for anyone. Whole swaths of Boston became unsafe for people of color — and they would remain that way for years.

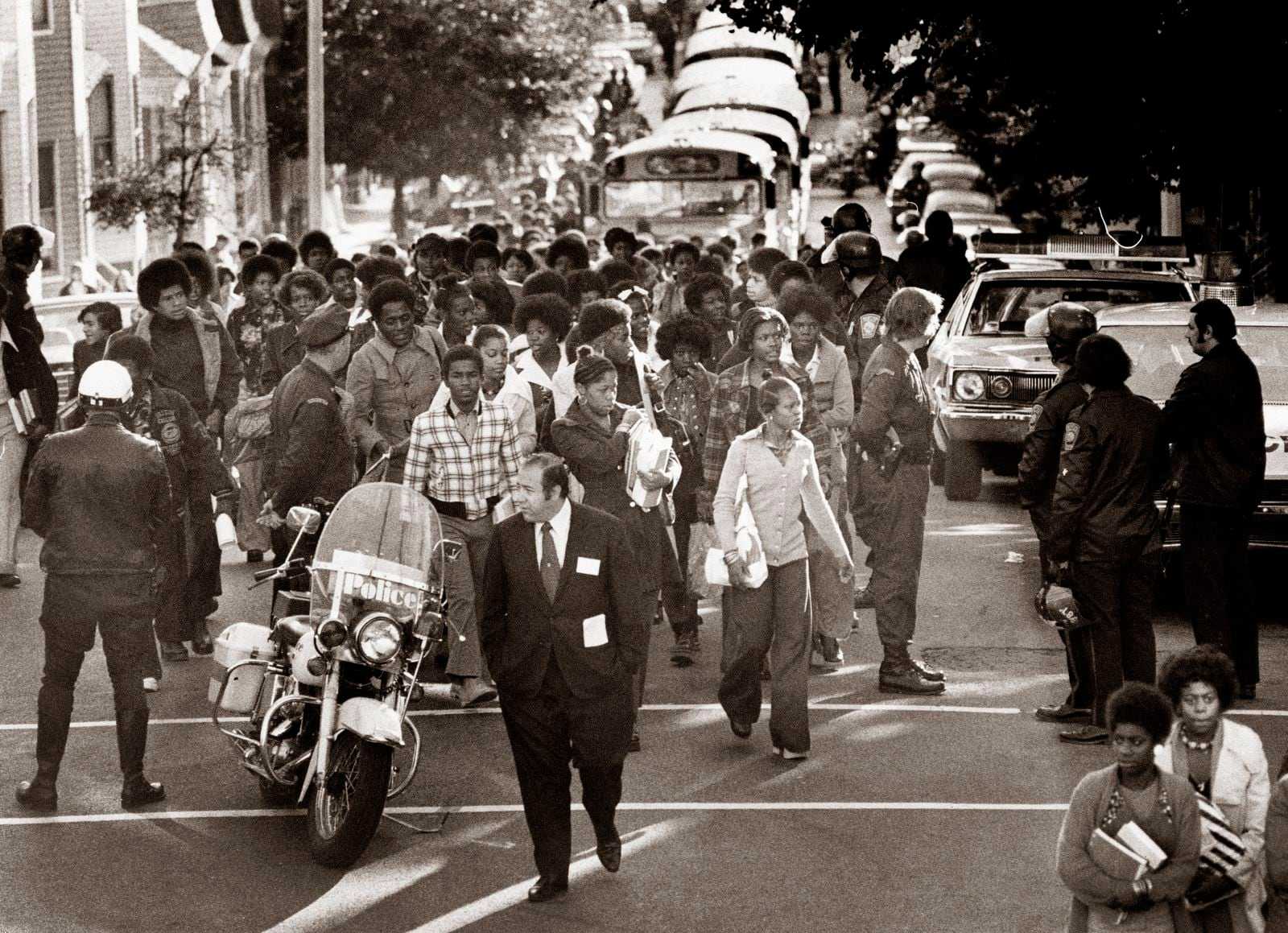

Still, Black families were undeterred. They demanded equity, and integration was the way to achieve it. Here, Black students leaving Hyde Park High School in 1976.

Students leaving the Columbia Point housing development for Roxbury High on the second day of school in 1974. Before Garrity’s court order, the white students on this bus would likely have been assigned to South Boston High. Note that the Black and white students are sitting separately.

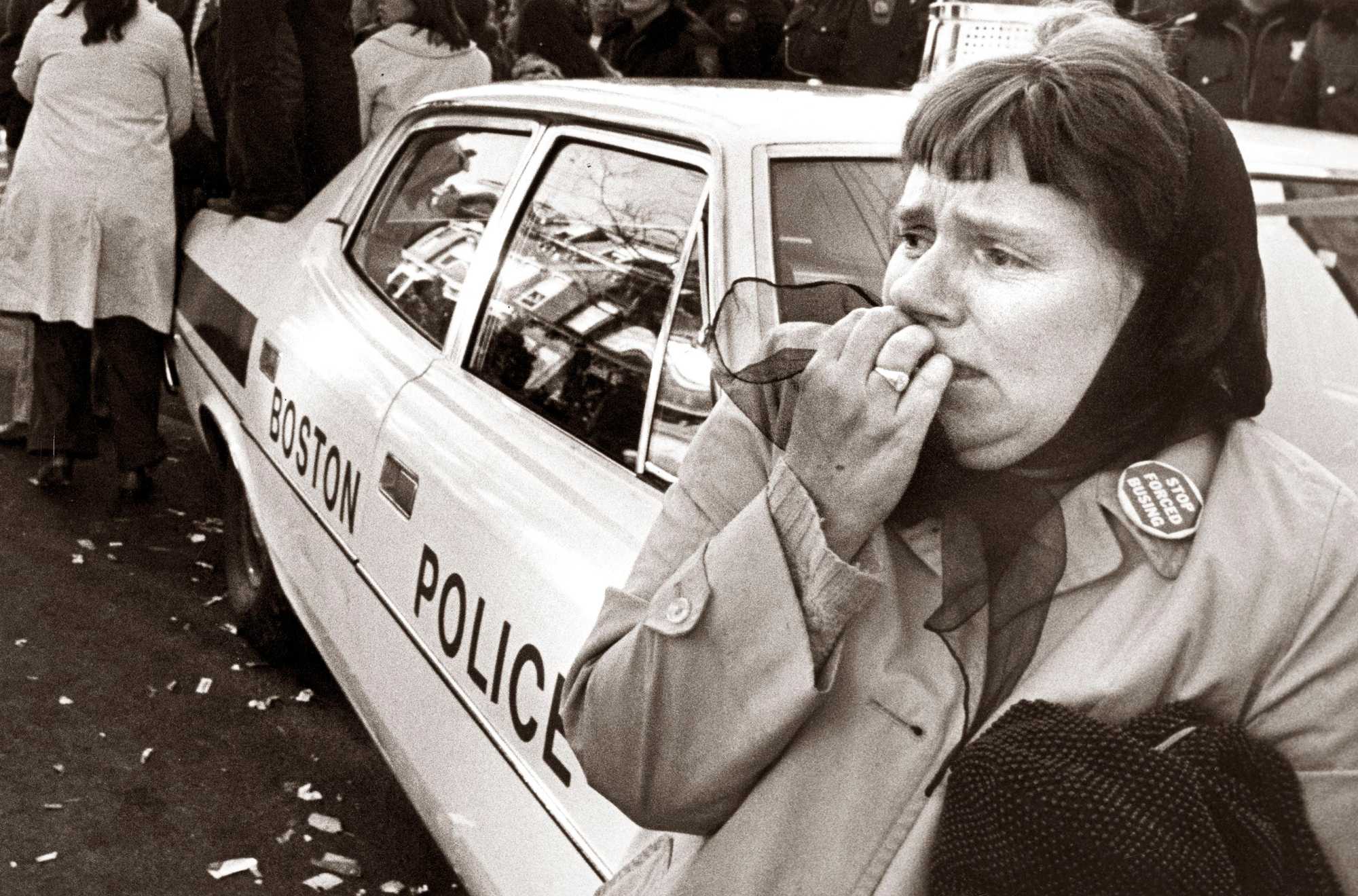

“Stop Forced Busing” was the mantra of aggrieved white residents of South Boston. Central to their sense of victimization was the idea that busing had been forced down their throats by a suburban judge who would never have to suffer its consequences. But the students they attacked hadn’t asked for that either.

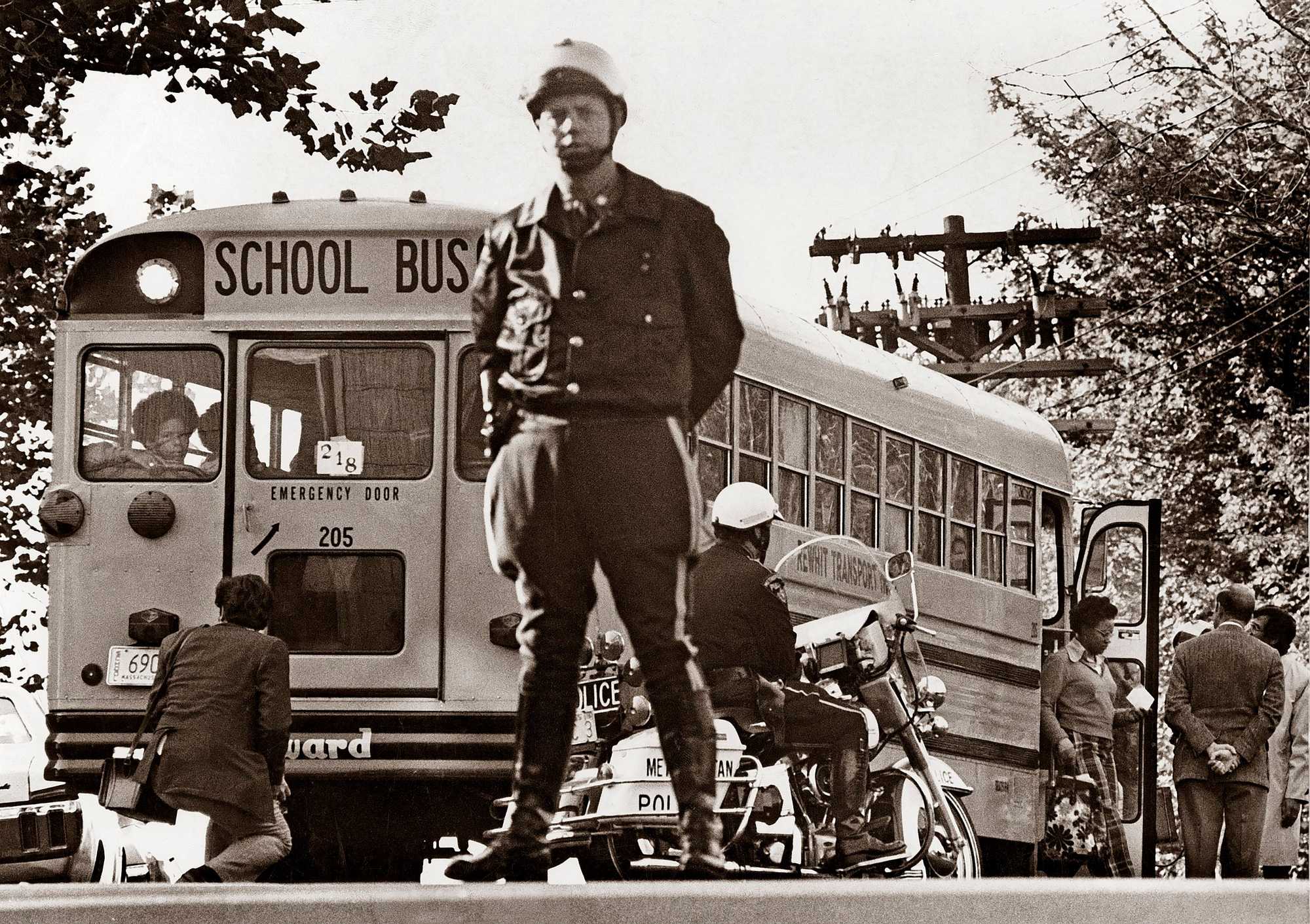

Multiple police departments would eventually be charged with protecting the safety of school buses, assisting an overwhelmed Boston Police Department. Here, officers from the Massachusetts State Police and the old Metropolitan District Commission police guard a school bus at Southie High.

Two Black students wait to leave their school bus outside South Boston High during the first year of busing. Their fear and apprehension speak for themselves.

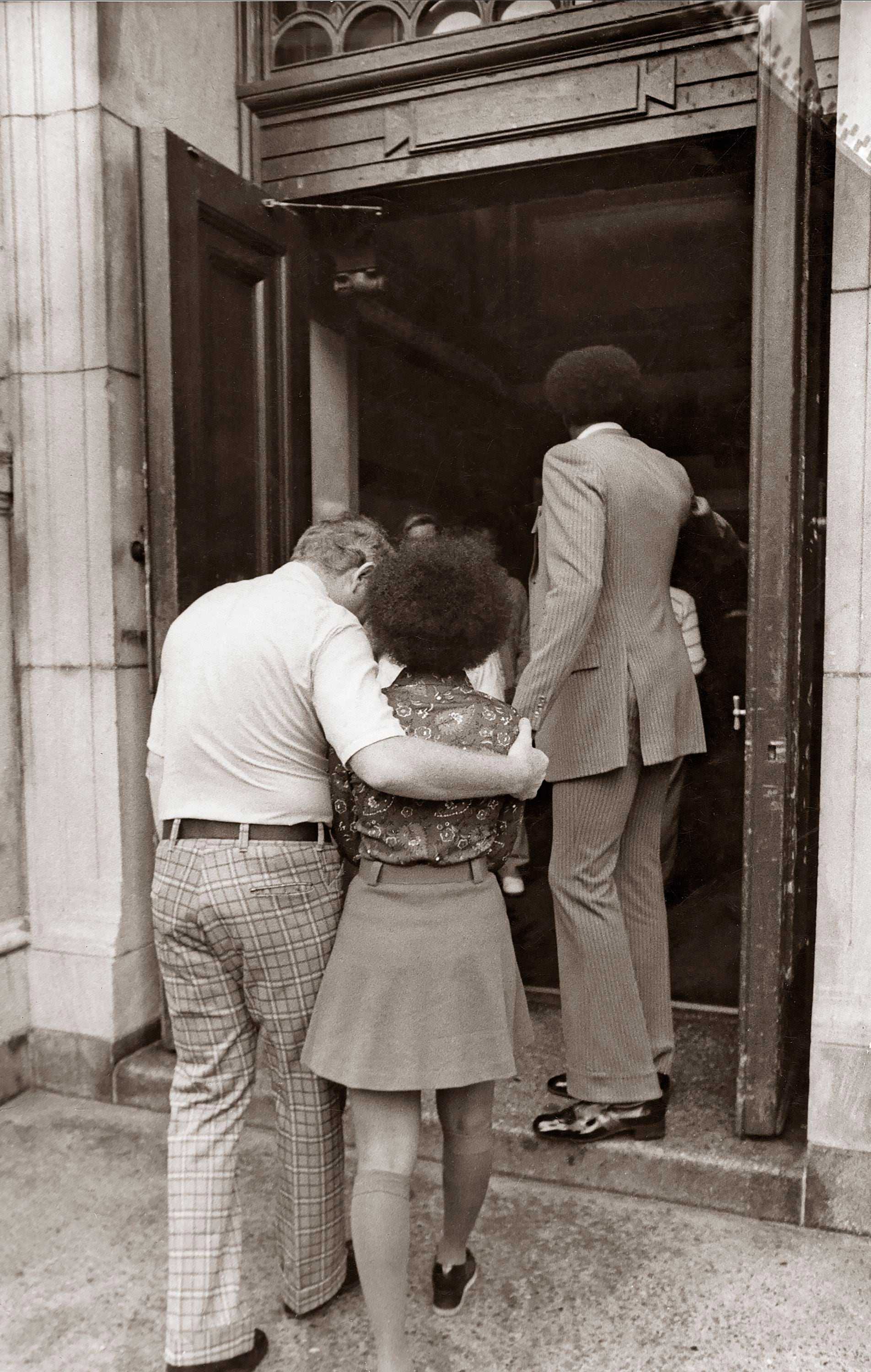

School leaders were often called on to offer emotional support for students, especially during the violent and anxiety-filled fall of 1974. Here, Roxbury High principal Charles Ray escorts a student through the door on the first day of school.

School was in session, but Roxbury High School was nearly empty on the first day of school in 1974, as white families being bused there almost all refused to go. Portraits of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy adorn the walls of this classroom, but this is far from the “beloved community” King dreamed of.

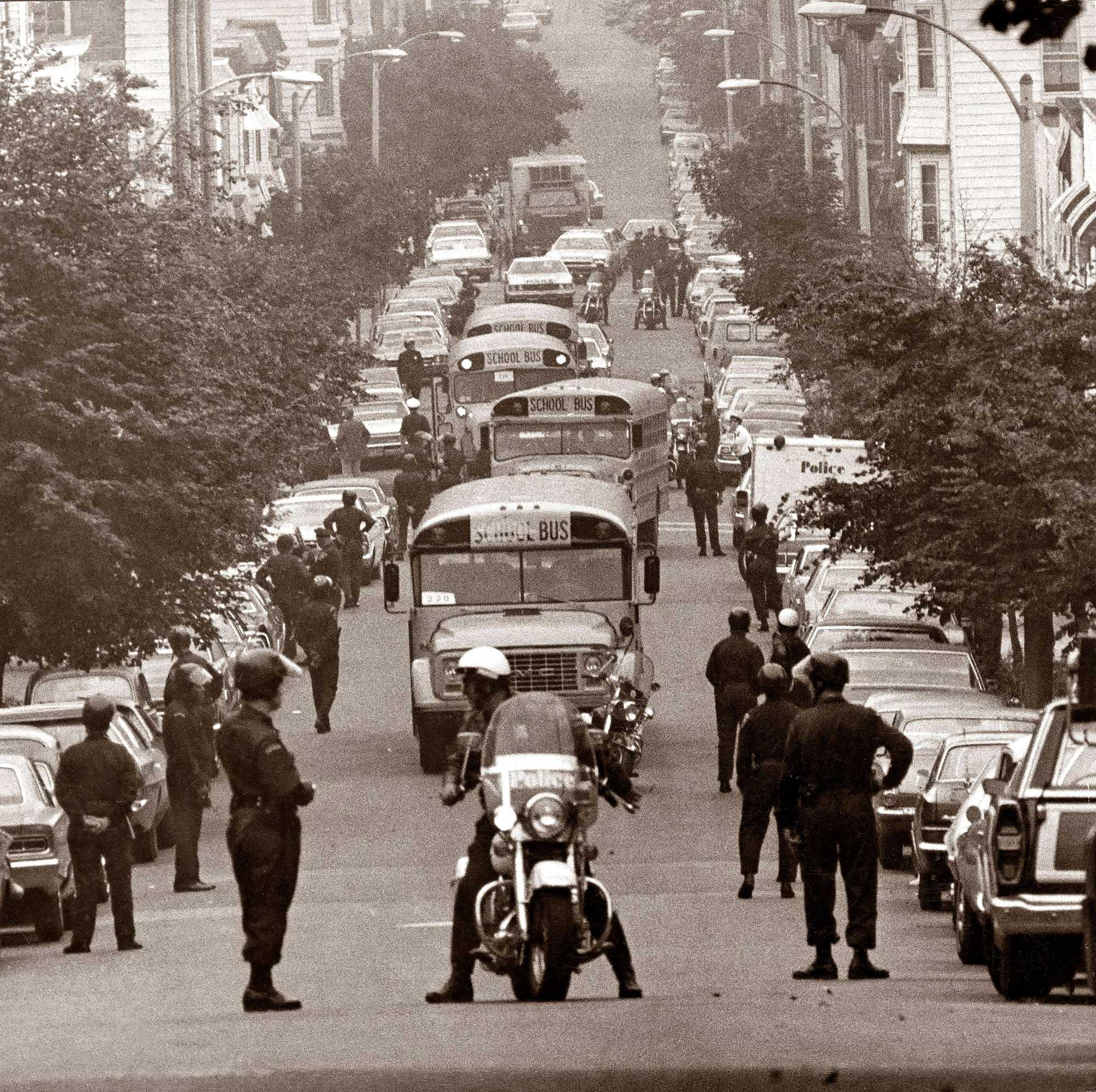

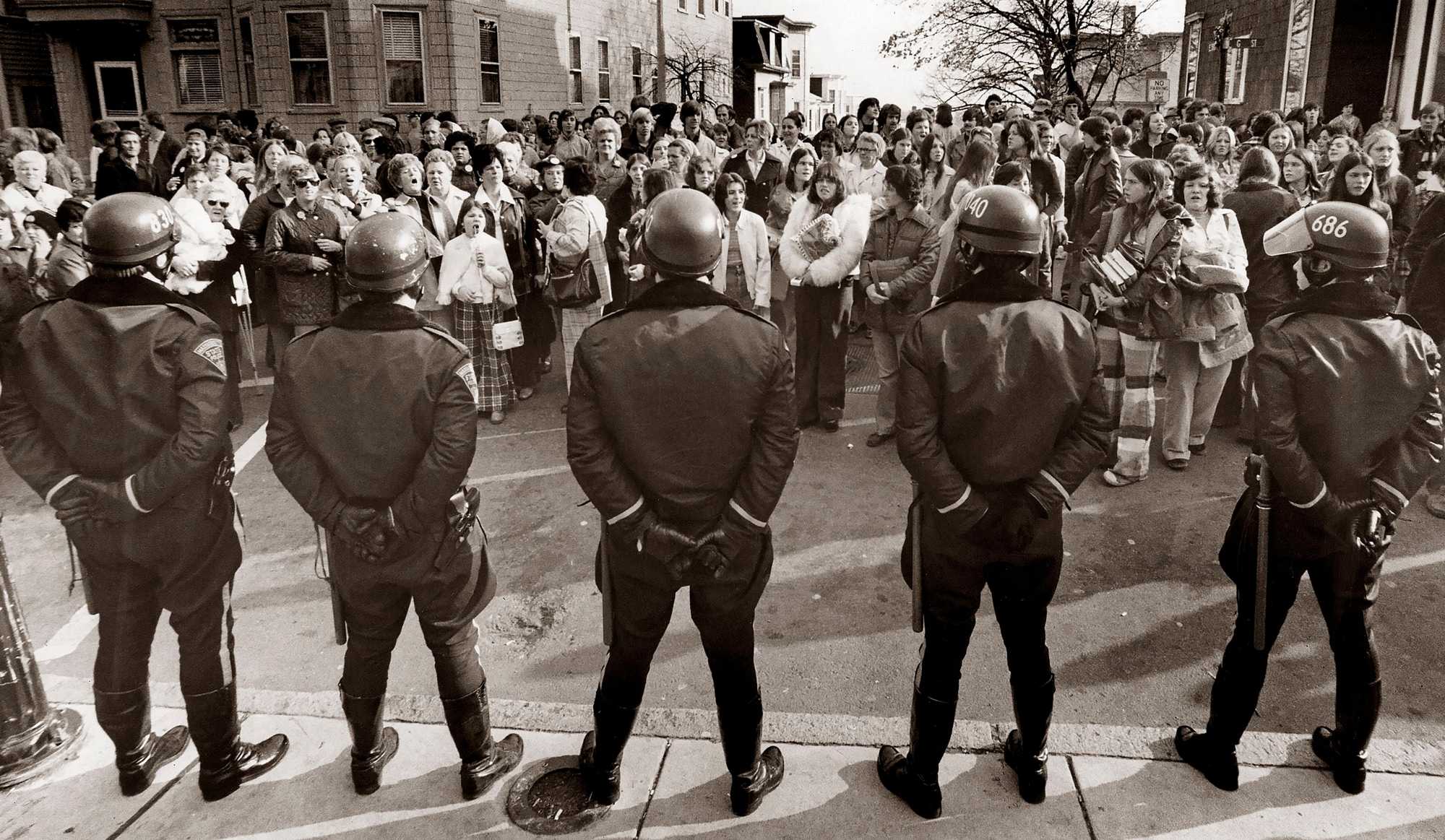

Police holding back a crowd in South Boston on the first day of school in 1974. The neighbors weren’t there to extend a warm welcome. Quite the contrary.

School buses had never needed police escorts before, but that all changed in the fall of 1974. Here, buses are being led up the hill leading to South Boston High School.

Eileen Dunner of Dorchester was one of the relatively few white students who came to Roxbury High on the first day of school in 1974. White families would eventually leave the Boston Public Schools by the thousands, but before that many simply boycotted.

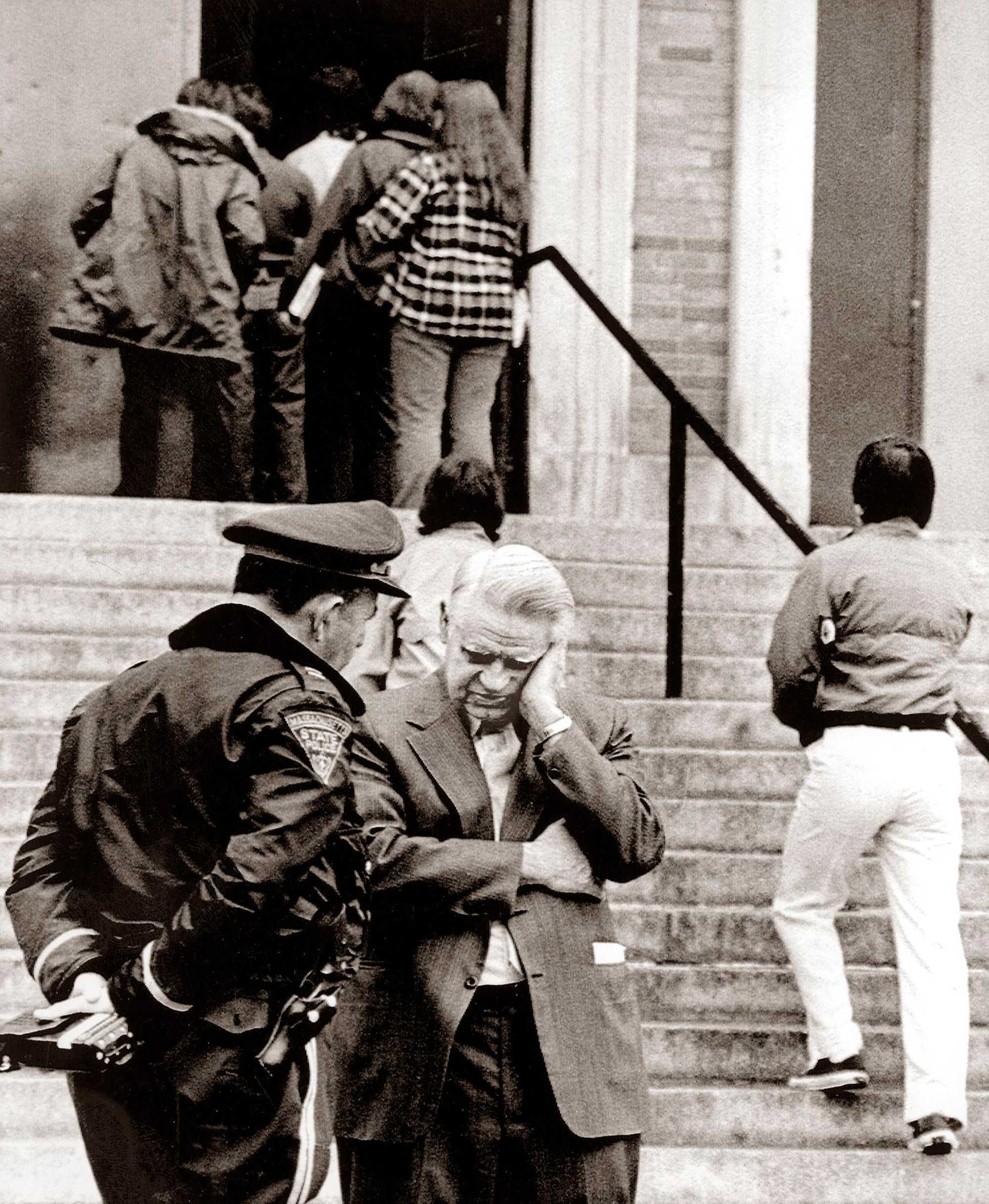

South Boston High headmaster William J. Reid talks to a Massachusetts state trooper as students file in. They were required to pass through a metal detector and be searched for weapons after the violence that accompanied the start of court-ordered desegregation. Reid may have had one of the most thankless jobs in Boston.

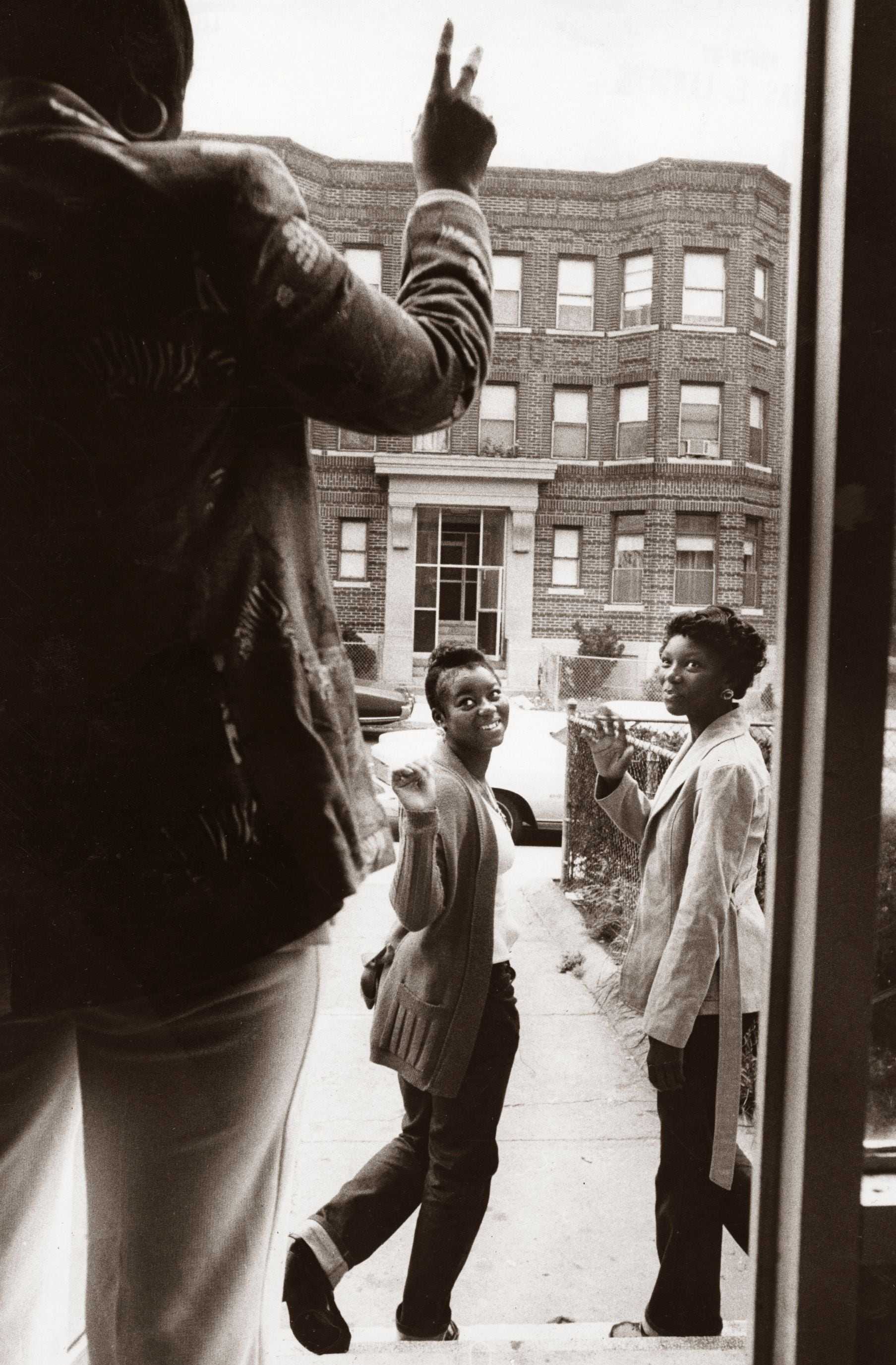

Teresa Graham (left) sends off her daughters Cynthia, 15, and Sylvia, 14, on the first day of school in 1974. For all the threats of violence, many Black families hoped that day would be the start of a new era of educational equity.

Hyde Park didn’t achieve the national notoriety of South Boston and Charlestown for opposition to busing, but it had no shortage of conflict. Here, police break up an after-school brawl among students in 1975.

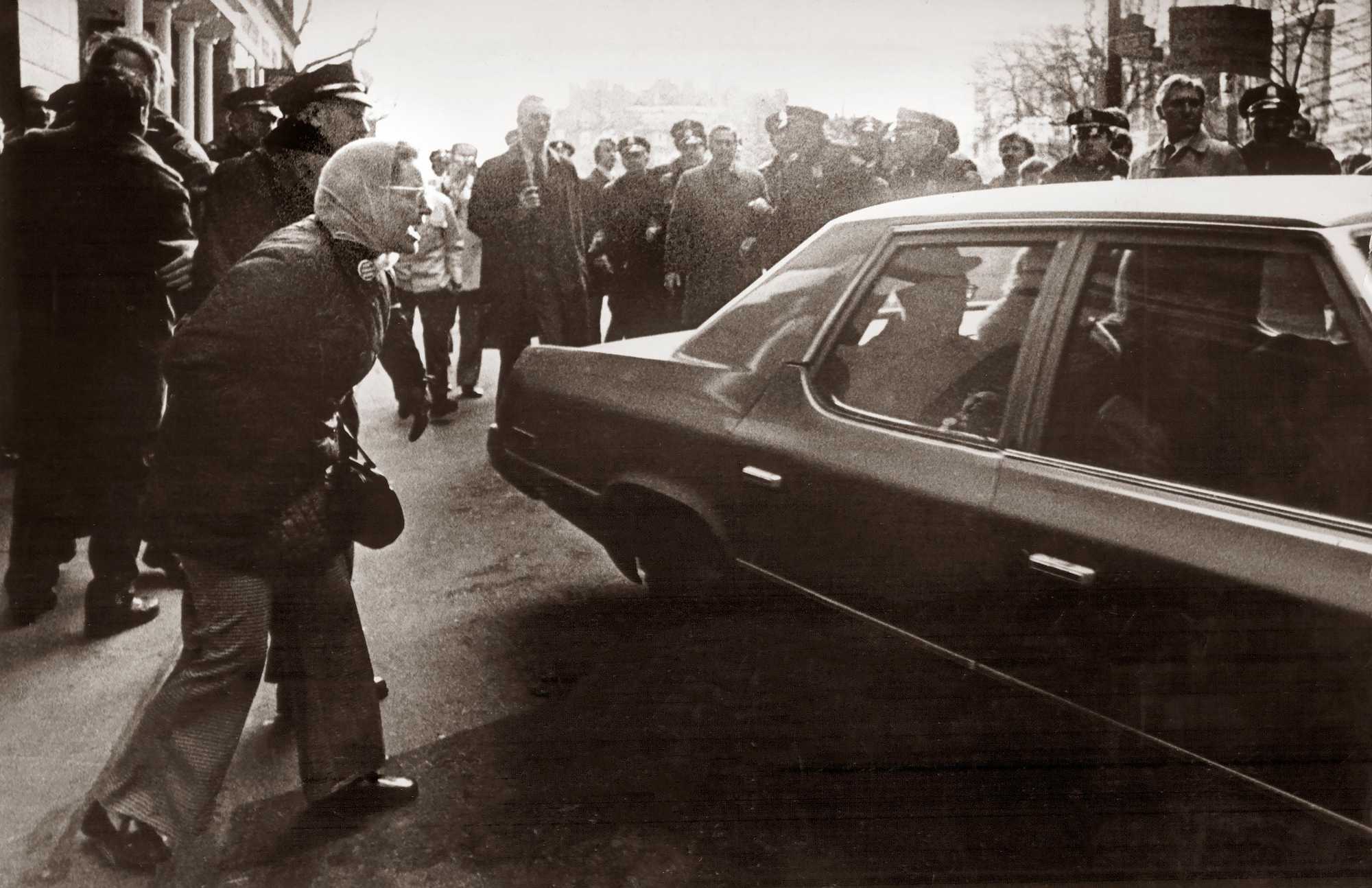

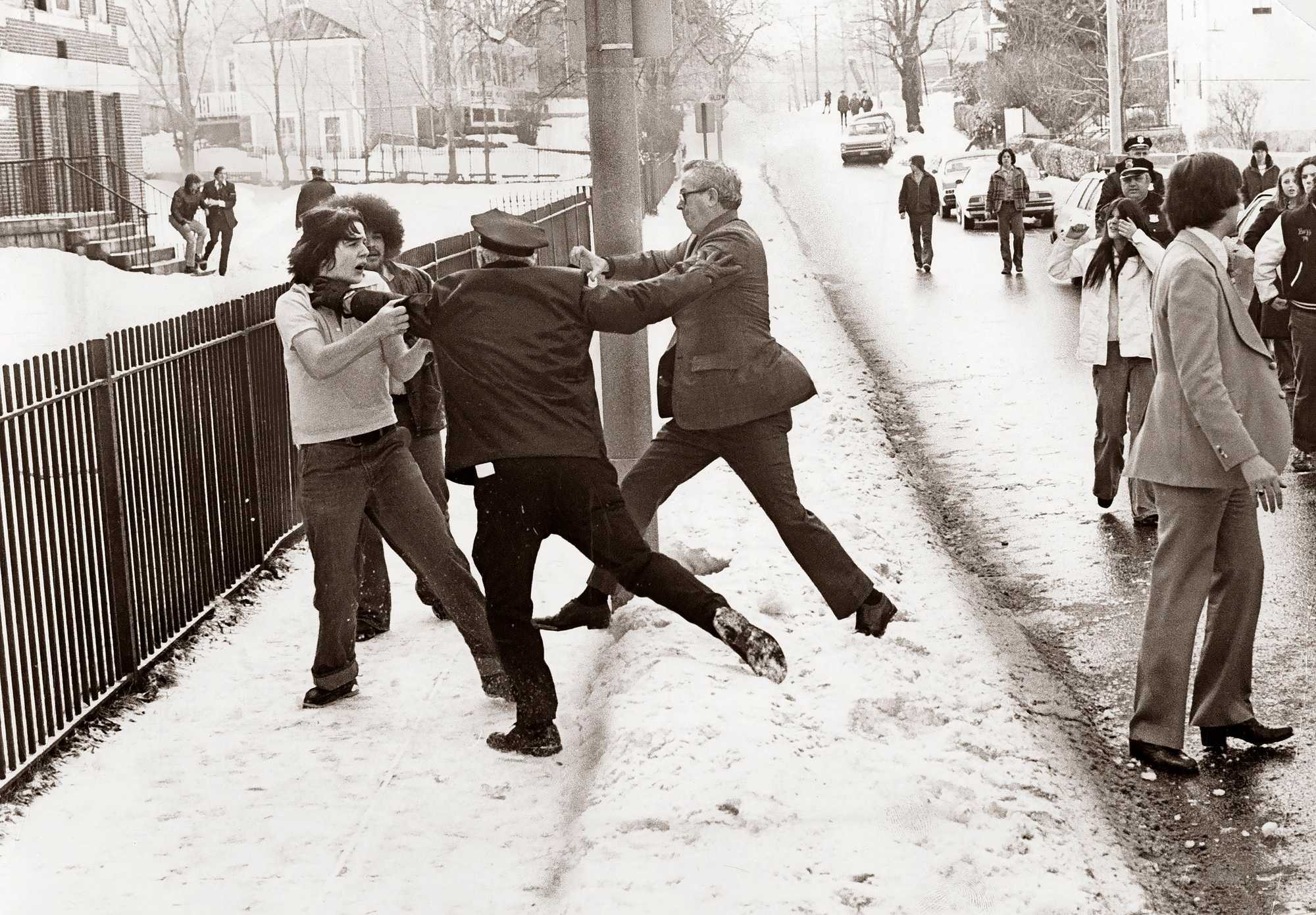

Garrity was given an award by the Massachusetts Bar Association in 1975 for ordering the end of school segregation. But he wasn’t universally celebrated. His critics weren’t shy about confronting him in person, either.

Mothers were a major force in opposing busing. Here, an anti-busing “Mothers March” in Hyde Park stops at the intersection of River Street and Hyde Park Avenue to pray in 1975.

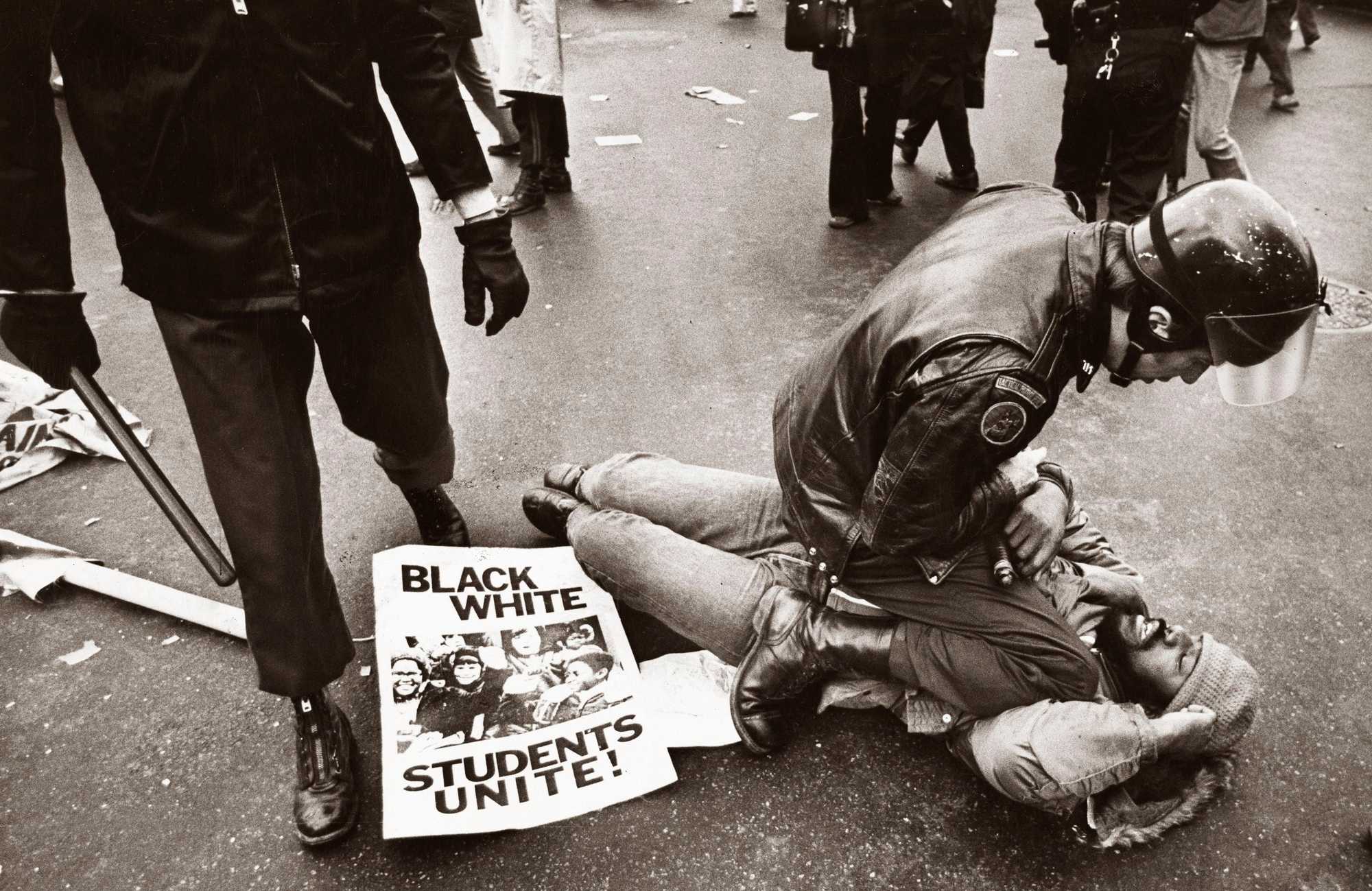

A pro-integration demonstrator was pinned to the ground by a police officer during a rally in 1974. Despite the plea on the flyer, unity was in short supply.

Often, defenders of busing protesters have been known to say, “Busing was never about race; it was about class.” This picture of fake KKK members tells a different story — racist zealots reaching for the most vile symbol of white supremacy they could think of. Even though Boston had not been Klan territory, blatant racism was never far from the surface in South Boston.

The Progressive Labor Party tried to hold a march against racism in May 1975. But these South Boston youth were not down with the cause — they chased them with sticks and stones. Ultimately 10 people were injured and eight were arrested.

This classic photo captured the violence visited on Black students on a school bus on the first day of school in 1974. Adults throwing rocks at young people was a daily occurrence during court-ordered desegregation.

A police line outside Southie High 10 weeks into court-ordered desegregation. Police would be a daily presence at the school for at least two years.

Yet another brawl outside Hyde Park High School — this one in 1976, during the second year of busing. Clearly, tensions were not cooling.

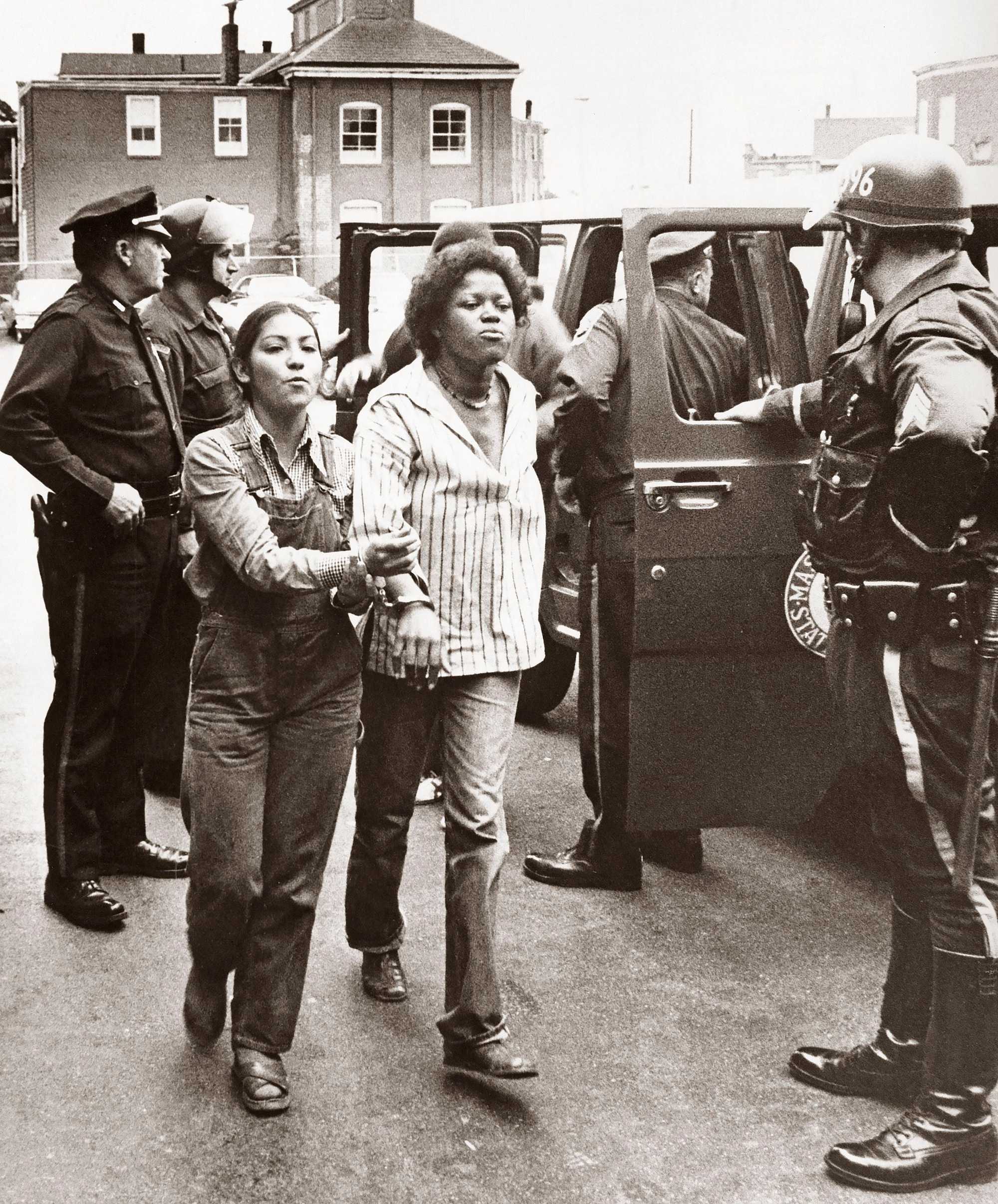

Police making an arrest in Dorchester in 1975, as activists attempted to support students who were being bused into hostile territory.

A crowd — actually, a mob — stands atop a Boston Police cruiser after a huge battle at South Boston High in December 1974. After a white student was stabbed inside the school, thousands of white protesters descended. Black students narrowly escaped the violence. One of the famous battles in Boston’s Civil War.

This story is part of a series produced by the Boston Globe’s Great Divide and Money, Power, Inequality teams. The Great Divide team explores educational inequality in Boston and statewide; Money, Power, Inequality covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporters: Mike Damiano, Christopher Huffaker, Mandy McLaren, Deanna Pan, Ivy Scott, Milton Valencia, Tiana Woodard

- Contributors: Niki Griswold, Lisa Wangsness, Marcela García, Adrian Walker

- Editors: Melissa Barragán Taboada, Kris Hooks

- Additional editors: Anica Butler, Cristina Silva, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Suzanne Kreiter, Jessica Rinaldi, Lane Turner, Craig F. Walker, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of Photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Video producers: Randy Vazquez, Olivia Yarvis

- Audio producers: Jesse Remedios, Scott Helman

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editors: Michael J. Bailey, Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Jenna Reyes, Adria Watson

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer, Adria Watson

- Homepage strategy: Peter Bailey-Wells

- Project lead: Melissa Barragán Taboada

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC