BROKEN PROMISES, UNFULFILLED HOPE

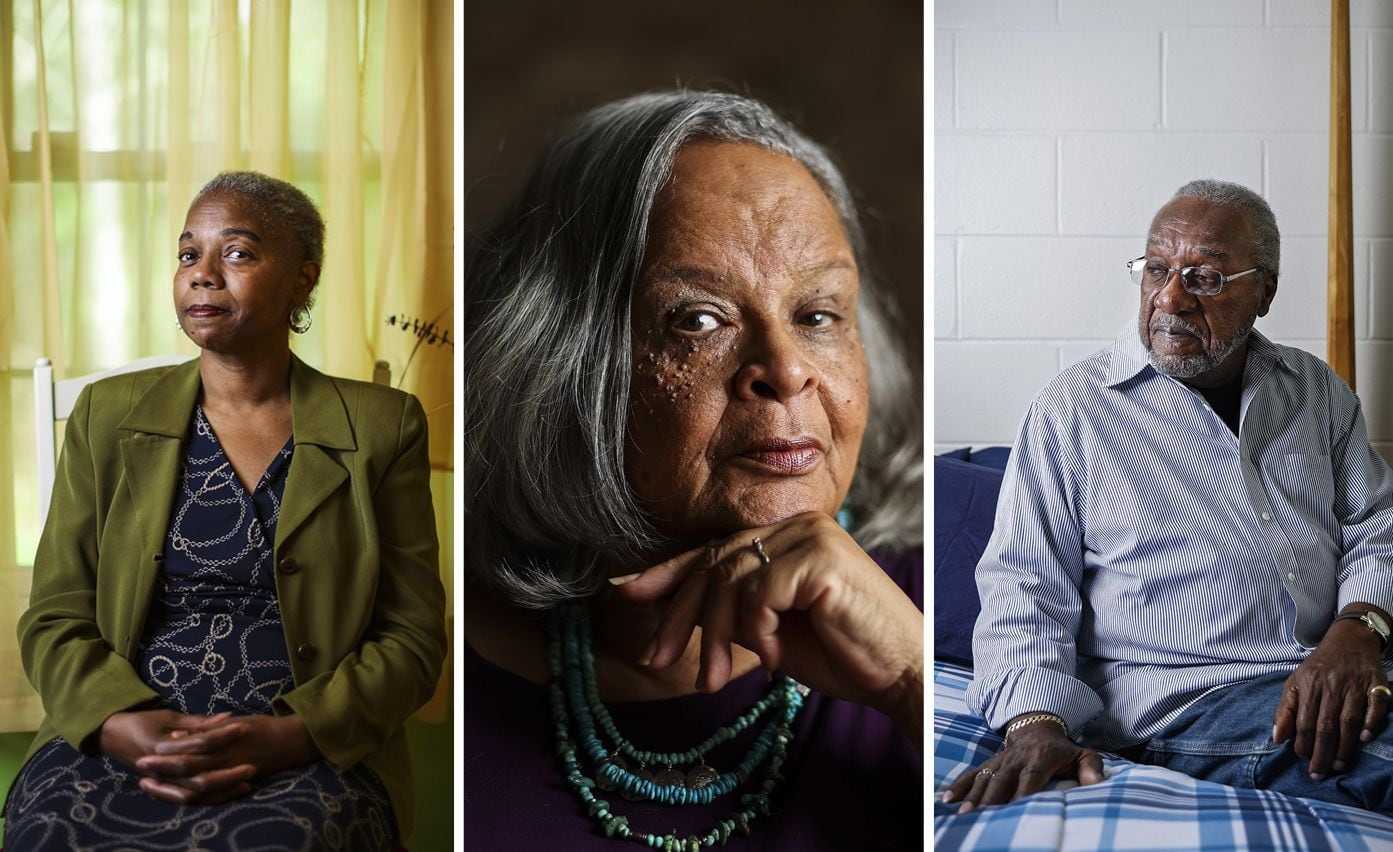

Meet the families whose lawsuit forced BPS to integrate

They were teachers, clerks, counselors, and activists. But above all, they were parents. The 14 families behind Morgan v. Hennigan, the 1974 federal decision to desegregate the Boston Public Schools, only wanted the best for their children — and they were willing to sue to get it.

The families were largely shielded from the limelight, while lawyers, community organizers, and other civil rights activists made appearances about the case. Some never publicly spoke of their reasons for signing onto the lawsuit until now. The Globe found 13 of the 14 plaintiff families. Ten agreed to be interviewed. Here are their stories:

Read the story of Earline Pruitt, her family, and their reckoning with the legacy of busing here.

Diane Bassett

“You had Black schools and you had your white schools. Both said they were teaching the kids… [but] in Roxbury, the books that they were teaching the kids from, [compared to] in the white communities — same grade — were totally different. We were just asking for an education. Same education the other kids are getting. The same books that they’re learning from, we want our children to learn from.

00:00

/ 00:00

She heard whispers of classrooms where the teachers didn’t teach, where students received passing grades on quizzes when the only correct answer on the page was their name. No teacher, she was told, seemed troubled by the fact that Black students were given completely different books to read than students in white schools. Older books. Simpler.

“That wasn’t going to happen to my children,” she said. Her oldest son, Kyle, was in kindergarten at the Boardman School, and Bassett was in the building almost every day.

Determined to demand high-quality schools for her children, she attended a School Committee meeting one evening. In the elevator, she recalled, one of the administrators spat in her face.

“We weren’t regarded as human beings,” she said. “They thought they ruled you, they were better than you. You were to do what they said, [and] how dare you stand up against them.”

Signing onto the lawsuit was her final effort.

In September, her children attended the Dennis C. Haley elementary school, but Bassett kept her eyes on other schools in the city as they struggled, not just to integrate, but to educate. When a year passed with little change, she decided to leave. In 1975, the family moved to Middleborough.

“I had to get out of Boston,” she said. “I needed all my children getting the best education possible.”

Advertisement

Pamela and Fern Burdette

“Fern: “Education is very important to me, because if you don’t have education you won’t succeed.” Q: “Do you have other memories of her, in big or small ways, communicating to you guys that education was important?” Pam: “Verbalizing it and saying, you have to do well in school, you have to study, again you know, like she said, reading to us. Being involved in more than just social things but educational things too. It was always like learning something with all the things that we did so if it wasn’t formal education in a school environment it was education in other ways to be exposed to different things, different people, different areas.”

00:00

/ 00:00

Decades before she was a plaintiff, Fern Burdette was a new transfer student at Hingham High School, after her family moved out of the city and into the suburbs. She walked into her Advanced Placement French class eager to pick up where she’d left off in Boston. But she was stunned when her new teacher launched into the lesson in fluent French.

“I expected it to be a little bit different,” she said. “But I didn’t expect this.”

Throughout her years in Boston, she’d always excelled, but now she was floundering.

“I was an A, B student in Boston, but I moved to Hingham [and] I flunked every subject in high school,” she said.

Burdette was forced to drop out of advanced French and repeat the introductory level class. The guidance counselors were supportive and encouraging, but the shock and embarrassment took a toll.

“I just could not do it,” she said. “That really devastated me.”

Burdette worked hard to improve her grades through the rest of high school, but she never forgot how ill prepared she felt on that first day of school. Those memories flooded back when she learned about the pending lawsuit as a young mother in Boston, and quickly agreed to sign on to end discrimination and improve the city’s schools.

Pamela Burdette Miller, Burdette’s daughter, said she was both proud of her mother for joining the fight, and grateful her mom made good education a priority, ultimately transferring Burdette Miller and her siblings out of BPS.

“I’m proud of her for raising us the way that she did,” Burdette Miller said, recalling how her mother read to her and her siblings nightly. “It was always [about] learning something, with all the things we did. If it wasn’t formal education in a school environment, it was education in other ways.”

Advertisement

Adrienne Alston

Daughter of Mary Crockett

“I went to my mother one day and I said, ‘Mom I want to go to Metco, I want to go to Newton High.’ Because I know that’s a very nice neighborhood and everything. And she said, ‘Adrienne, we want to make it good for all the Black kids.’ And so she said, ‘Adrienne, sometimes in life you gotta sacrifice something to get something better for the masses.’ And me, being a person who’s, I’m pretty smart you know, I can understand, so I was like OK. I’m still angry, don’t get me wrong, I'm still mad, but I don’t let her know, you know. Because I know she’s trying to do something amazing.

00:00

/ 00:00

A young Adrienne Alston was nearing the end of middle school and desperately wanted to apply to join the city’s Metco program. For years, she took extra classes at Milton Academy, a private school outside Boston, to overcome her speech impediment. The kind and attentive faculty left her longing for all the benefits suburban education seemed to offer, compared with her dingy Dorchester classrooms.

Her mother, Mary Crockett, couldn’t deny the allure, either. Her eldest daughter attended Brookline High, where the curriculum reminded her of her own high school education. It was remarkable, she thought, that growing up in rural West Virginia had somehow afforded her better schooling than most of her children were getting up North.

Resources were certainly sparse at times, but even in a segregated, Blacks-only school, Mary Crockett read Shakespeare and Chaucer, which felt far from what Black schools seemed to offer in Boston. That was why she’d joined the lawsuit: to bring those opportunities to Black students across the city.

Sitting across from her teenage daughter in the living room, Mary Crockett prepared to deliver the hard news.

“Now, you know that I and all the other parents were working on that case against Boston Public Schools,” Alston recalled her mother saying. “We want to make it good for all the Black kids … [so] we have to see this through.”

Her daughter stared back at her, struggling to understand. She was set on Metco, and getting accepted to a suburban school.

“I know, Mom, but that’s the case. That don’t have nothing to do with me,” she insisted. “I just want to go to a good school!”

After a long pause, her mother replied: “I know you do, but that wouldn’t be right. ... Adrienne, sometimes in life you gotta sacrifice something, to get something better for the masses.”

Advertisement

Tashia Burton

Daughter of Arthur Eskew

“I think as a Black man, like, shoot he was born in 1920-something, you know what I mean, let’s be honest like, what he experienced in life, from a Black man in that era, I’m sure that had an impact on him. I’m sure. Like If you were raised in that era, as blatant as it was, racism and the disadvantages, you would probably feel some kinda way. You would feel some kinda way. You know, so I think he felt some kind of way. And I think he did something about it.

00:00

/ 00:00

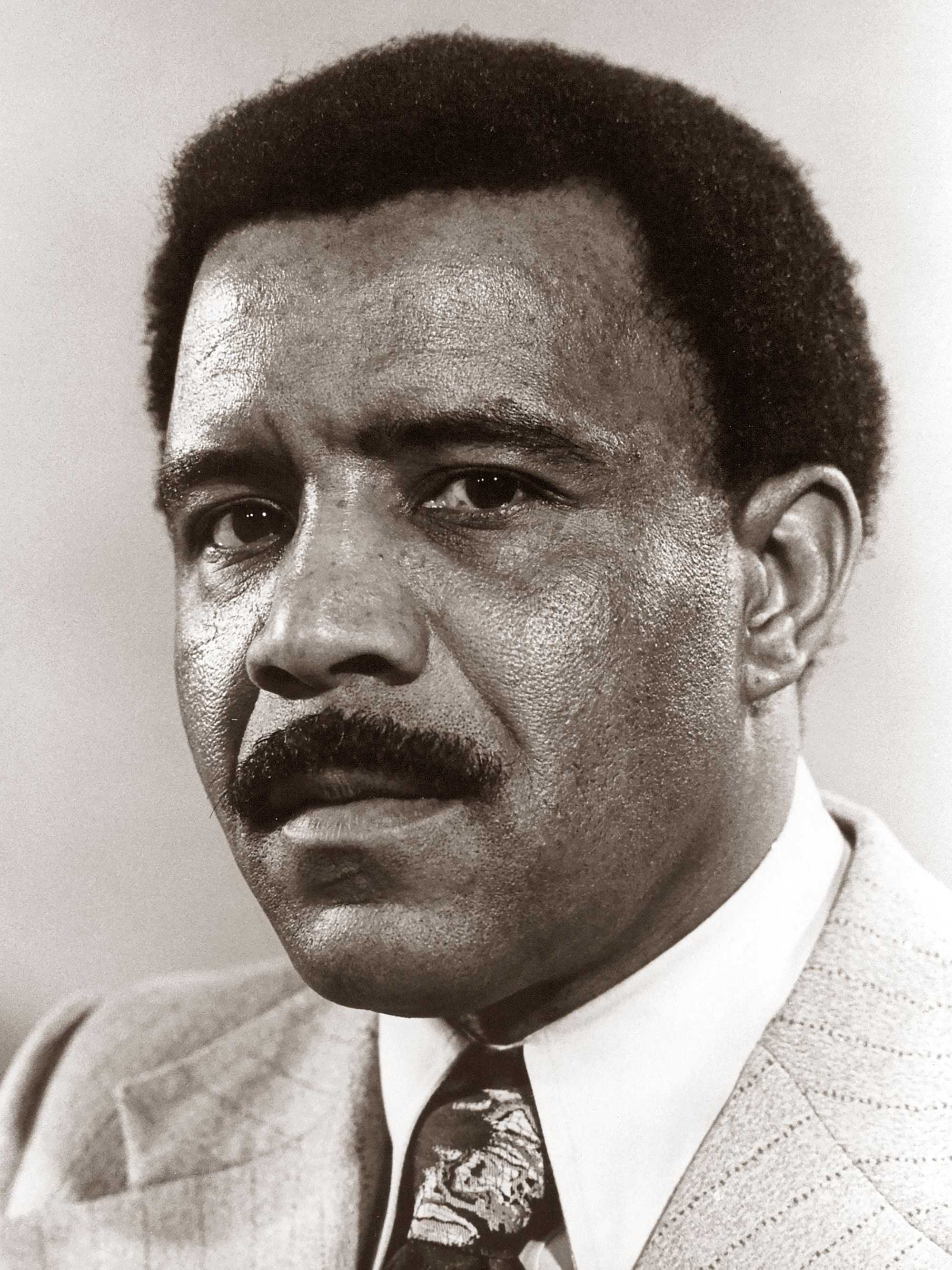

With no more than a sixth grade education, Arthur Eskew joined the military and arrived in Boston a veteran in need of a job. Through the Nation of Islam, he found work at multiple community organizations and became a vocal advocate against economic and educational discrimination.

“He was a facilitator,” said his daughter, Tashia Burton. “Whether he was [teaching] real estate or fixing up a house … we knew he was taking care of business, either on our behalf or someone else’s.”

Despite his lack of formal education, Eskew quickly gained a reputation as “the neighborhood teacher.” And he made it clear to his children that he expected them to pursue the quality of education he never had, putting them in SAT prep courses and signing them up for summer classes.

While his daughter would rather have been playing outside with her friends at the time, she now celebrates how Eskew’s dedication built a better future for her family and other Black families in Boston. His decision to join the court case, she said, was no different.

“His thought was: Let me move the needle forward,” Burton said. “‘I’m not going to sit back and just allow this inequity that I know is here, and do nothing about it.’”

Eskew died in 2012, but Burton said he would be proud to be remembered as someone who pushed for fairer, more equitable education in Boston.

“He would always say, ‘I’m planting the seed, now you’re going to grow from it,’” Burton remembered.

Lorraine Johnson-Graham

“I was like a little stone in a big, big pond, but I also felt… proud? I don't know if proud is the right word. It gave me a sense of purpose to be a part of trying to make change, and it was exhausting and it was very painful. It’s painful because in spite of, that fight continues.

00:00

/ 00:00

On the fifth page of a yellowed copy of the Bay State Banner newspaper is a photo of Lorraine Johnson-Graham, beaming into the camera at roughly 30 years old. Beside the photo, a brief story details one of her proudest accomplishments: going back to school and earning her master’s degree in education, after dropping out of high school at age 16.

The article she’s kept for more than 45 years opens with a mantra she’s often repeated to herself in life’s most difficult moments: “Don’t settle for less than you are worth.”

Johnson-Graham’s upbringing amid Boston’s racial tensions in the 1950s made this sentiment difficult to internalize at times.

“I remember one of the little [white] girls saying to me, I wasn’t too bad because I was lighter skinned, and could look like her,” Johnson-Graham said. “I was in elementary school, but I never forgot that.”

Later, her mother sent her to a predominantly white middle school in Dorchester with the hope she would receive a better education. But Johnson-Graham’s peers continued to make it clear that they equated “Black” with inferior.

“The pain, the loneliness, there was nobody there for me,” she said. So “I learned to care about the underdog.”

After leaving high school, getting married, and having her first child, Johnson-Graham found a mentor who encouraged her to return to school. Her mentor also taught her what it looked like for underdogs — like herself and other Black mothers in Boston — to fight back through grassroots activism. She became a vocal advocate for school desegregation, marching alongside Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1960s, and later signed onto the Boston schools case.

Though she is proud of her role in the lawsuit, Johnson-Graham ultimately enrolled all three of her children in the Metco program, unwilling to risk exposing them to the same circumstances she faced.

“There were a lot of wounds,” she said. “I didn’t feel safe sending my kids into Boston.”

Advertisement

Karen Means

Daughter of Grace Means

“As a kid I didn't pay that much attention. She would, you know, have meetings and stuff like that, or go out. But it really surprised me that she was involved in that. And then I remember a few things about meetings, you know, with Louise Day Hicks and Mel King, and how he interrupted one of the meetings by putting a dead rat on the table, stuff like that. It surprised me and it pleased me greatly. Very very proud of her. I mean the fact that she finished college working full time with seven kids and a dog tells you: she's strong. And directed.

00:00

/ 00:00

Grace Means was not a woman who crumpled beneath the weight of life’s obstacles. When her husband was killed in a construction accident not long after the couple bought their first house, Means was left at 31 with no job and seven children.

“Using the little money she had, she buried Daddy, moved us into the house, and finished paying for it,” her daughter, Karen, remembers. “One marvels at how she did that.”

Over the objections of her young children, who clung tightly to her before her first day of work, Means got a job as a secretary with BPS to support her family. It was there she observed firsthand the conditions of the city’s schools and was prompted to join the lawsuit.

Means, who died in 2009, wanted her children to aim for a college education, and set an example by putting herself through school while working full time.

“She used to fall asleep at the typewriter doing her homework,” Karen said.

Karen remembers her mother being “horrified” at the conditions of the BPS schools in Boston’s Black neighborhoods. At the very least, Means thought children of color deserved class materials that weren’t falling apart, and to see themselves represented in the teachers and curriculum — and she was willing to fight for it.

“She was amazingly stubborn,” Karen said, “but it served her well.”

Glenn Murphy

Son of Mary Murphy

“I got accepted into Metco way before my two siblings underneath me. They went to the public schools at least two years before they came in so they got bused out to South Boston. One went to South Boston, the other one went to I think East Boston. But they got it bad. They’d be crying, ‘I don’t want to go.’ But, you know, they had to get their education. My mother felt, probably, she just had to make a change. You got my parents and parents like my mother, they come from the South, and all they want to do is do better for their kids. And, you know, you deal with all this inequality, and you deal with the violence that goes along with it, and all you want to do is give your kids a good education.

00:00

/ 00:00

Mary Murphy was the product of a church committed to raising strong, Black women.

She went from being on welfare to working for the city’s welfare office in Grove Hall. She and her friends, other church-going Black women, looked out for one another. If one had to work late, the others could be counted on to supervise and feed the kids.

She was petite but had a commanding presence and high expectations. She enrolled her four boys in piano lessons, tap classes, and African dance, and took them on field trips to New York City to see Black theater — anything to broaden their education in and out of the classroom.

Signing onto the lawsuit seemed like a natural next step in the fight for racial equality. But after one of her sons was assigned to South Boston High School, where grown men beat the school bus with sticks and yelled racial slurs at the small, Black faces in the windows, she began to fear for her children’s safety, and moved the family to Cambridge.

In Boston, �“you got treated like Roxbury was the ghetto,” her son said. “So it was a matter of wanting us to have some diversity, and for us not to be labeled as this little Black ghetto child.”

Robert Phillips

Son of Carrie Phillips

“Leaving from the Jamaica Plain projects to go to Sudbury, Mass., it was a dramatic difference money-wise. You went from a poor neighborhood to a rich neighborhood to go to school, so that was a shock right there. … But it definitely was better. I started waking up a lot earlier, like 5 a.m., to get to school, but when I was younger I actually loved school. I used to say every day, ‘I can’t wait to go to school!’ There was good teachers out there, they never let nobody slack. [Not like in Boston, where] they didn’t care whether nobody was learning or not — you could fall asleep in class and they didn’t care.

Raising three boys in a housing project in Jamaica Plain, Carrie Phillips had rules for her home. She didn’t hesitate to wake her sons up to finish the dishes or put the laundry away. Homework had better be done before dinner.

Through Phillips, her sons also became steeped in the struggles of the civil rights movement, as their mother routinely marched the city streets demanding racial equality.

“My mother was a revolutionary,” said her youngest son, Robert Phillips. “She was all about Black power.”

In their family, the plight of Black people in America — and in Boston — felt personal. For Phillips, the differences in education between Black and white became starker after the case was decided: While her older sons went from attending Black public schools to being bused to South Boston High, she enrolled her youngest, Robert, in the Metco program at age 8. He attended school in the wealthy suburb of Sudbury.

As his brothers endured racial slurs on their way to school, and instructors who didn’t care if you fell asleep in the classroom, Robert Phillips loved learning from kind, attentive teachers. But leaving the projects for an affluent, white suburb helped him better understand what his mother was fighting for.

In the battle for equality and justice, better education wasn’t a lofty ideal — it was the way out of poverty.

“When you’re being treated badly, you want your rights,” he said, “to get out of the situation that you’re living in.”

Denise Pruitt

“It was all about the negativity and all the bad that happened. And there was a lot of bad. Don't get me wrong, there was a lot of bad. But despite it, some of us were able to achieve in life and continue to achieve in life. And that really needs to be the narrative that, you know, you tried to break us and you didn't. But nobody wants to hear that. Nobody wants to hear that the little Black girl made it.

00:00

/ 00:00

The roar of the mob softened as Denise Pruitt hustled up the staircase, through the metal detectors, and inside the hallway of Hyde Park High on her first day of school. The clamor of a harrowing bus ride was replaced with relative quiet as a hall monitor guided Pruitt to her locker and walked her to first period, the screams outside fading with every step deeper into the building.

When she entered the classroom, everything became quiet. All heads turned to stare at her, and for a moment she stared right back, taking in her new surroundings. It wasn’t half bad, she decided. The books looked newer, the desks less scratched-up, and the walls brightly painted.

“My middle school was dilapidated and really had little to offer. So I left dreary and dingy to go to this fabulous big building with clean lockers, and it was like night and day,” Pruitt said. “It was the disruptions … all the picketing and the violence, that took away from that.”

Eyes still on her, Pruitt searched the room for another dark face. She landed on a young Black teen and sat down promptly next to him. As she waited for the first bell to ring, she couldn’t help but wonder who she’d make friends with first, whether her teachers would be nice, and what new topics she’d learn this year.

When her mother signed onto the case, she explained it was because she wanted to see better public schools in their family’s neighborhood of Dorchester. And though busing was a little different than what they’d hoped, Pruitt thought maybe Hyde Park would be all right.

Richard Yarde

“I just didn't think that integrating the schools was gonna happen. I never thought that that would happen because I kind of assumed that these communities were never going to accept these kids. And as a fact, they really didn’t. And I looked at it as, it’s gonna be difficult for these children to get an education, going somewhere where they’re not accepted, they’re gonna be ridiculed. I couldn’t see how anybody could learn. Even as an adult, in that kind of a situation, it would have been difficult to learn. But I went along with it anyway because I just figured something needed to happen.

00:00

/ 00:00

Less than 10 years out of the Marine Corp, Richard Yarde still felt the instinct to protect and defend daily. As busing was underway, Yarde worked as a bus monitor on routes that traveled through South Boston and Hyde Park, and resolved he would not let harm come to a single child on his bus.

“Keep the kids safe, keep some peace and calm … that’s why I did it,” he said.

It wasn’t easy, watching grown men degrade children that reminded Yarde so much of his own son and daughter, who went to BPS schools and would ultimately graduate from West Roxbury High. But his own time in the military and years organizing with the Black Panther Party made him able to spot trouble brewing from afar. What he saw that first day of busing hardly surprised him.

“These other communities didn’t want ‘em, and everybody knew it. It was just dangerous,” he said. “I don’t know how they could actually get involved in a lesson plan after the bus ride they just came off of — having to be escorted into school by the police, and snuck around back entrances.”

After years of failed attempts to improve conditions in Black schools, Yarde was more shocked that the court had ruled in favor of desegregation in the first place. His goal in joining the case was just to bring attention to the fact that children attending Black schools in Dorchester and Roxbury were not being well served.

“I didn’t think it was going to work, and I still don’t think it was successful at all,” he said. “But I went along with it anyway because I wanted something to happen.”

This story is part of a series produced by the Boston Globe’s Great Divide and Money, Power, Inequality teams. The Great Divide team explores educational inequality in Boston and statewide; Money, Power, Inequality covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston.

Globe staff writer Niki Griswold contributed to this report.

Credits

- Reporters: Mike Damiano, Christopher Huffaker, Mandy McLaren, Deanna Pan, Ivy Scott, Milton Valencia, Tiana Woodard

- Contributors: Niki Griswold, Lisa Wangsness, Marcela García, Adrian Walker

- Editors: Melissa Barragán Taboada, Kris Hooks

- Additional editors: Anica Butler, Cristina Silva, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Suzanne Kreiter, Jessica Rinaldi, Lane Turner, Craig F. Walker, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of Photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Video producers: Randy Vazquez, Olivia Yarvis

- Audio producers: Jesse Remedios, Scott Helman

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editors: Michael J. Bailey, Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Jenna Reyes, Adria Watson

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer, Adria Watson

- Homepage strategy: Peter Bailey-Wells

- Project lead: Melissa Barragán Taboada

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC