BROKEN PROMISES, UNFULFILLED HOPE

In the order to integrate Boston schools, Latinos were an afterthought. They’re still fighting for equal education today.

The small windowless room looked more like a custodial closet than a classroom. Fifty native-Spanish-speaking students were crammed inside. The young teacher, who spoke only English, had given up trying to maintain control of her students, who were laughing and screaming dirty words at one another in Spanish while she sat quietly at her desk.

It was 1972, and Carmen Pola, whose third- and fourth-grade daughters were in the classroom at Farragut Elementary School in Mission Hill, was appalled by the scene she encountered while visiting the campus.

“They were yelling at the top of their lungs and she couldn’t do anything because she wasn’t bilingual,” Pola recalled. “They wanted attention.”

This was no isolated outrage. At the time, Boston Public Schools offered very little in the way of support for Latino students, like Pola’s children, whose numbers were relatively small — a few thousand in a system of 95,000. Most of them were Puerto Rican, spoke little to no English, and were taught in overcrowded classrooms with limited resources and subpar instruction.

But for the language barrier, their plight was much like that of the Black students BPS was serving so poorly in those years — they too were students systematically shortchanged by racist school leadership. But in the tumultuous battle to desegregate the city’s schools — a quest that climaxed in a historic federal court order mandating busing to integrate the schools — Boston’s Latinos felt like an afterthought.

Because they were.

Advertisement

The Boston branch of the NAACP had sued the city’s obdurate School Committee on behalf of Black students and their families in 1972, and Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. ruled in their favor two years later. But Garrity’s 1974 order in Morgan v. Hennigan said nothing of the fate of Latino students and other students still learning English. The district’s “Hispanos,” as Garrity called them, were mentioned in a single, lonely footnote that stated their treatment could be considered at future hearings.

Boston’s Latinos shared something else with the Black students of that era — bitter disappointment that the busing order, when it was handed down, mandated just about nothing that would improve the education the schools offered. For Latinos, that meant nothing about the substandard curriculum, or scant bilingual offerings, or the dilapidated condition of the many school buildings that had been allowed to languish because they had served students of color.

While not as stark as the inequities of the busing era, many of those failings persist now.

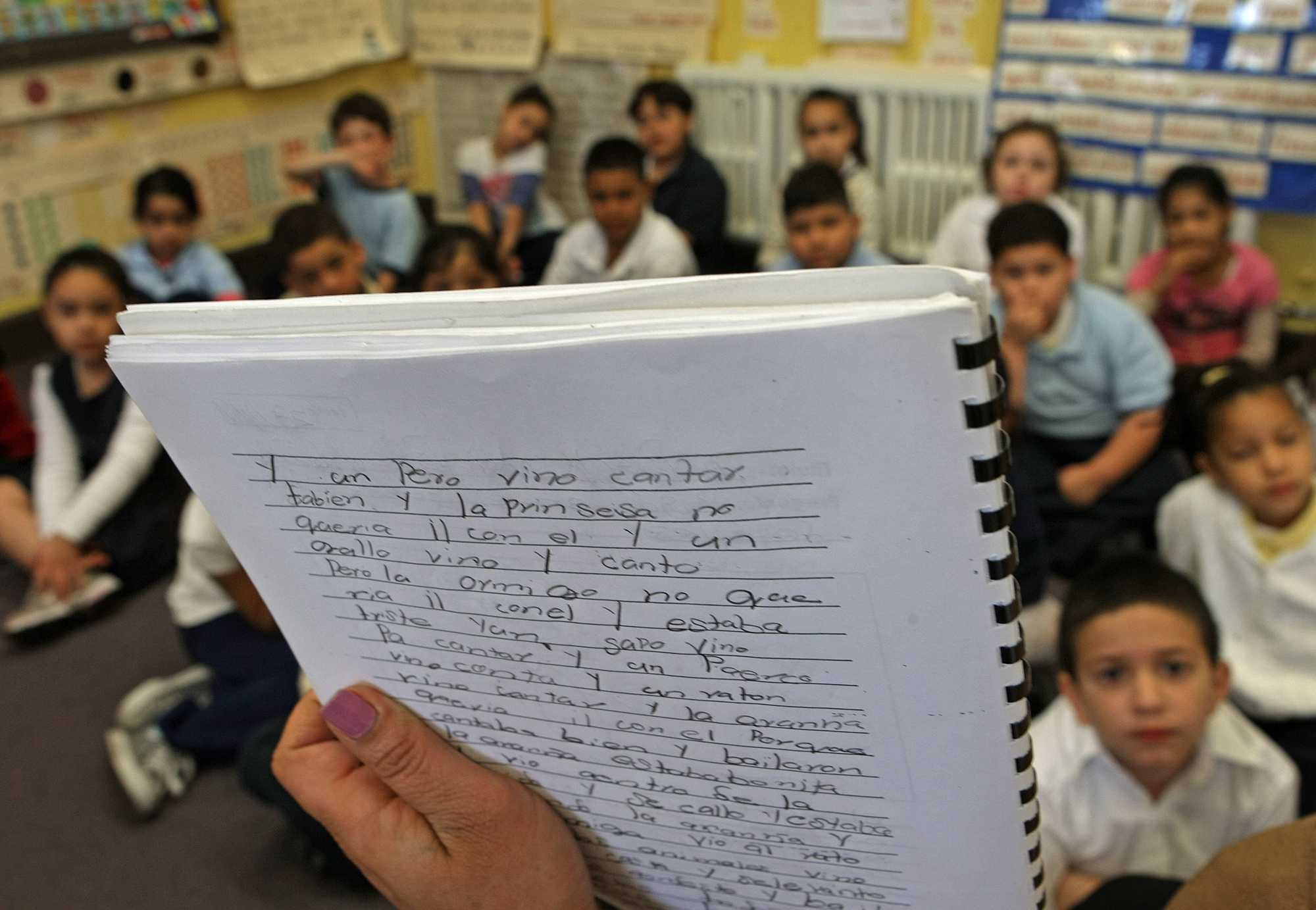

BPS still struggles to serve the needs of its English learners, leaving many Latino parents locked in the same battle as their predecessors. As they did two generations earlier, these parents, long after the passage in 1971 of a landmark state law requiring students with limited English proficiency be taught in their native tongue, are still fighting for more access to bilingual education and better support for students struggling to learn English. Just 7 percent of English learners in BPS are enrolled in dual-language programs and schools.

Today, Latinos make up close to half of the district’s 47,000 students, by far the largest racial or ethnic group in BPS, and roughly 40 percent of them are classified as English learners. Latino students’ graduation rate in 2023 — 77 percent — was 10 percentage points lower than that of their white peers. They also had the highest dropout rate last year — 11 percent — compared with Black, white, or Asian American students.

Students learning English in Boston, who represent about a third of the district’s population, lag even further behind, with their graduation rate double digits lower than the district’s average and their dropout rate nearly twice as high. Last year, less than half of the district’s elementary-age multilingual students and just 13 percent of multilingual high schoolers made progress learning English, according to state assessment data.

“The vast majority [of English learners] are not getting the kind of services that they should,” said Alan Rom, a civil rights and labor attorney, who has represented Latino parents in BPS over the years in their fight for equal education.

Ana Carolina Brito, principal of the Rafael Hernández School in Roxbury, where K-8 students are taught in both English and Spanish, said she would love to see the district expand dual-language programs, “but if we do deliver on that promise to families, we need support.”

Sixteen-year-old Dereck Medina can attest to the value of bilingual education. In 2017, Medina and his mother were displaced by Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico and evacuated to Massachusetts. He started at BPS when he was in the sixth grade. Despite not being fluent in English, Medina received no language-specific services. Often, his teachers handed him an English-Spanish dictionary. Sometimes an aide helped him translate his assignments. Learning English on the fly was hard and made schoolwork — particularly math, his least favorite subject — even more challenging. He left BPS at the end of eighth grade for a charter school.

“I didn’t feel like I could belong without knowing the language,” he said. “It was more or less a lonely time.”

Advertisement

Partway through his freshman year, Medina returned to BPS to attend the Margarita Muñiz Academy, the district’s first dual-language Spanish-English high school. For Medina, now a sophomore, attending the Muñiz has been transformative: He and his friends communicate in a medley of Spanish, “Spanglish,” and English, and argue about the subtle differences of Spanish dialects. His favorite class is Spanish humanities, where he’s learning about Latin American history and culture. For the first time in a long time, he said, he feels like he belongs.

“I’m able to learn both in my culture and my language. But I’m also able to learn in English and develop my English more than it already is,” he said. “That’s the best thing about my school.”

There were few such occasions for hope during the desegregation crisis and years of civil rights tumult leading up to it. At the time, an estimated 11,000 Spanish-speaking Latino children lived in Boston, largely in Roxbury and North Dorchester, but just 2,850 were enrolled in BPS, according to a 1969 report. The rest were effectively excluded from the district simply because there were almost no academic programs designed to serve them. A survey of the district’s non-English-speaking students in 1969 found more than 75 percent had been academically held back. In 1968, just seven Spanish-speaking students had graduated from high school in the entire city.

Even as he resorted to busing as a blunt force response to the racial animus suffusing BPS, Garrity didn’t rule on Latino students behalf because, while he acknowledged the presence of “other minorities” in the Boston system, he argued that no evidence had been presented to him showing these students suffered discrimination in the city’s segregated school system.

Garrity’s chosen remedy would, however, have indirect but adverse consequences for Latinos. Assigning students to schools on the basis of their skin color, as the judge’s plan required, meant many Spanish-speaking students would lose what few opportunities they had to learn in their native tongue. Bilingual education is possible only when large enough clusters of students with the same language background are in class together, explained Caroline Playter, an attorney who’d eventually represent Latino parents in the Morgan case. Under desegregation, Spanish-speaking children “were being dispersed all over the place.”

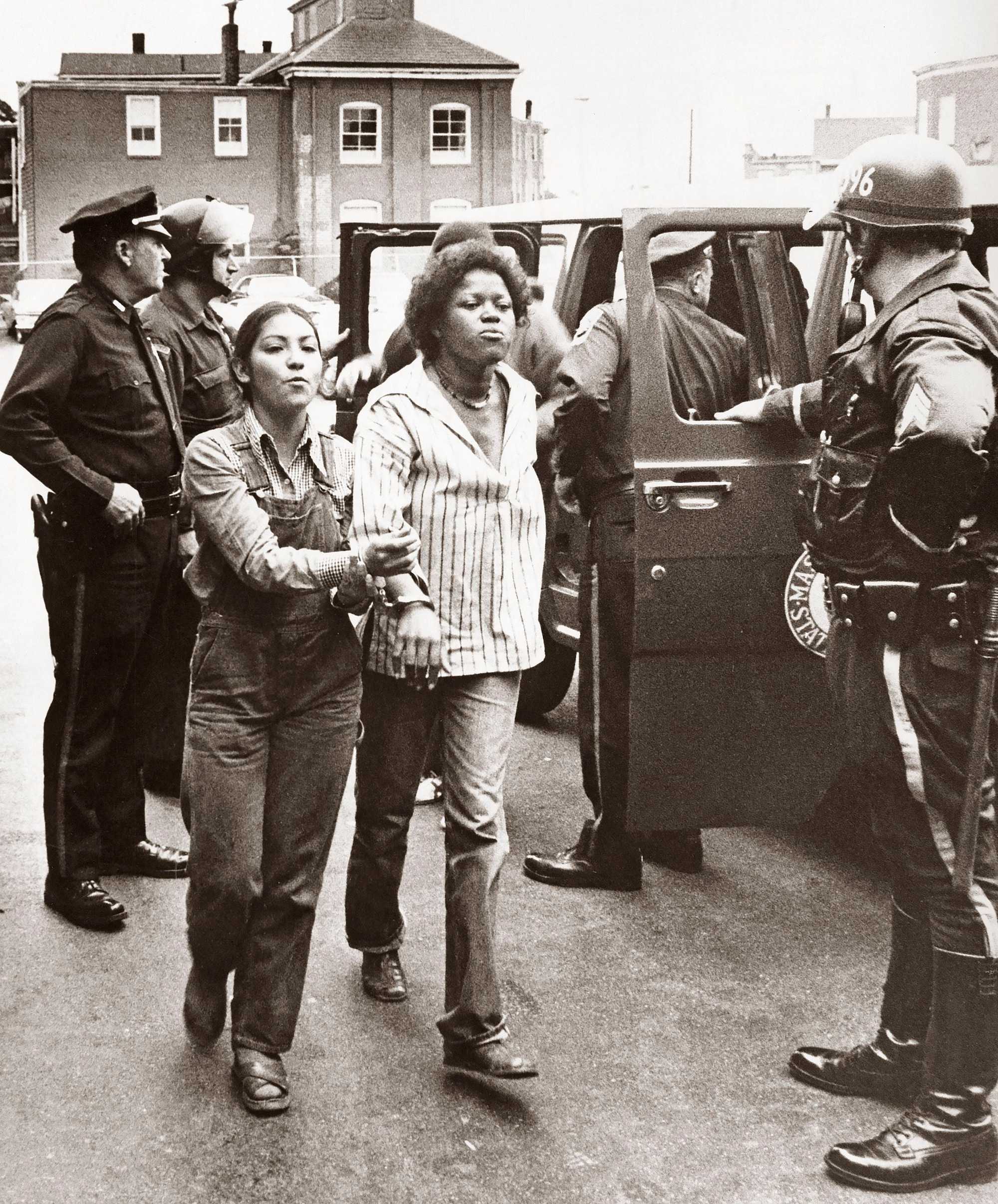

Indeed, to help schools achieve racial balance in the wake of the 1974 order, Latino students in Boston were arbitrarily classified as Black or white, to the fury of many Latino parents who feared their children would end up at different schools based on their skin tone or hair texture. David Cortiella, an activist, recalled twin brothers who were assigned to separate schools because one looked “Black” while the other looked “white.”

The 1974-75 school year “was just a mess in terms of the desegregation order — the master plan — that had been put in place,” Cortiella said.

Some in the community were determined to fight back. Pola, whose children were not getting the help they needed in school, was one of them. A seasoned community activist who had recently moved with her family to Boston from Oakland, Calif., Pola couldn’t let go of the mayhem she’d witnessed in her daughters’ classroom. She went door to door, mobilizing other Puerto Rican parents of students at the Farragut, so they could see, firsthand, the kind of education their children were getting. They pushed past the principal who had tried blocking them at the school door and marched into the classroom.

“They couldn’t believe it,” Pola said of the parents’ reaction. They went back to the principal and demanded a new classroom for their children and a teacher who could communicate with them.

Desegregation also meant the dismantling of the Hernández School, the hard-fought crown jewel of the Latino community, which almost exclusively served Puerto Rican students, who were taught all of their subjects in both English and Spanish.

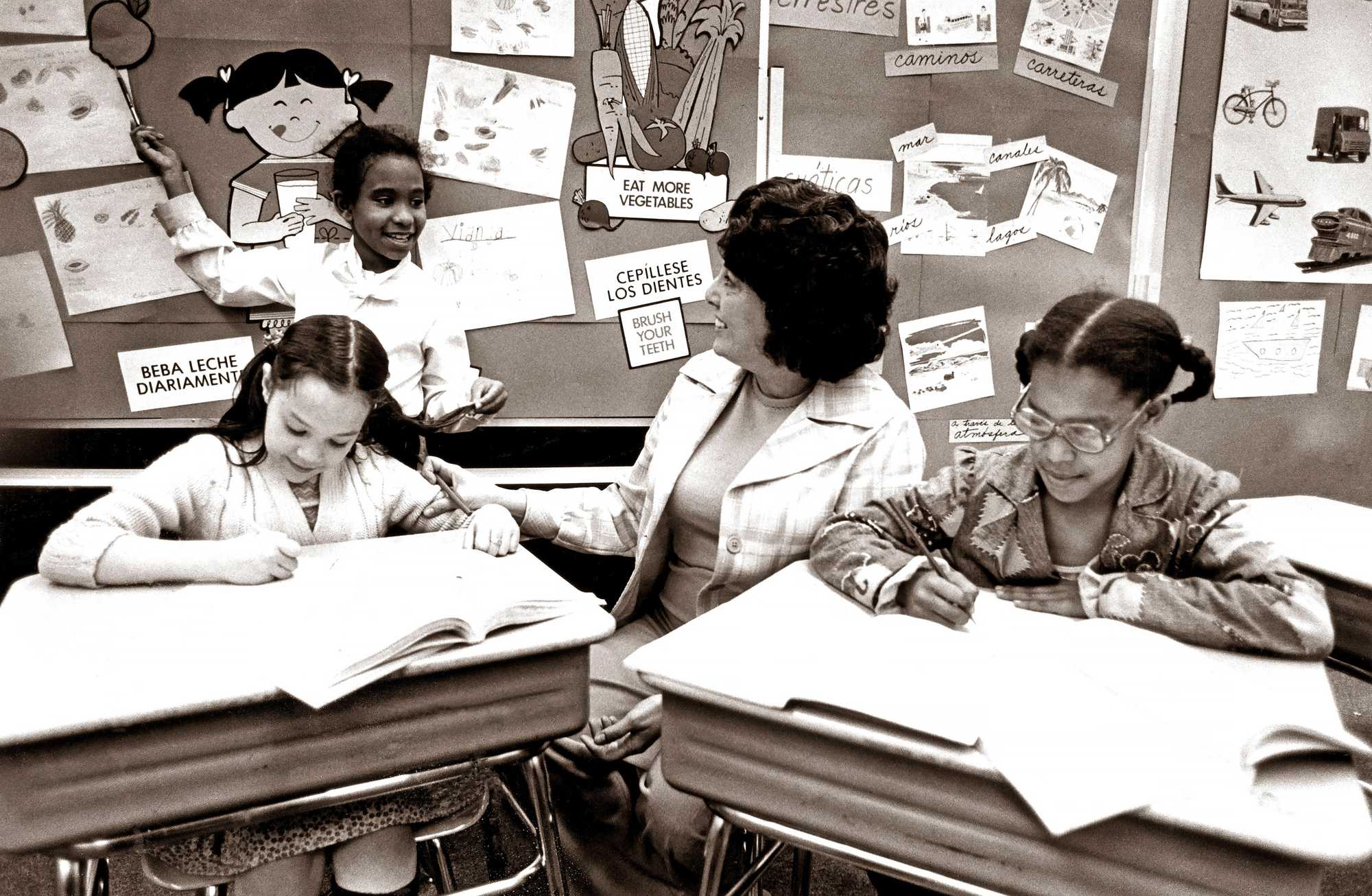

Teacher Mirta Torres instructed students at Rafael Hernández Dual Language School in 1978. (Bill Curtis/Globe Staff)

In January 1975, a grass-roots group of working-class Latino parents called the Comité de Padres pro Defensa del la Educación Bilingüe successfully petitioned Garrity to become a “plaintiff-intervenor” in the Morgan case, arguing that they were a class affected by the case’s outcome and so far, their voices had gone unheard. The Comité called on the court to classify Latino students as “Hispanic,” rather than Black or white, assign them to schools based on their specific language needs, and to compel the district to hire more Spanish-speaking teachers and guidance counselors.

Playter, the lawyer for the Comité, remembered marching alongside a group of parents representing eight languages, including Chinese, Vietnamese, Greek, and Italian, outside the federal courthouse for bilingual and bicultural education.

In a major victory for the Comité, Garrity adopted all of their recommendations in his revised decision in June 1975.

Advertisement

Their activism also saved the Hernández School, for which Garrity carved an exception in his desegregation plan, capping its enrollment at 65 percent Latino students. Today, the Hernández is nearly 80 percent Latino and 65 percent low-income, and students are thriving: More than three-quarters of students last year met or exceeded their targets on the statewide accountability measures.

“It opened the door for us to see that we are capable of changing things if we are together,” said Pola, who in 1980 became the first Latina to run for state office in Massachusetts.

But in the years following Garrity’s order, BPS failed to provide students the language services to which they were entitled, forcing parents to go back to the courts to intervene. In another setback for multilingual learners, a 2002 ballot measure outlawed bilingual education in the state until it was overturned 15 years later.

Today, multiple Spanish-speaking BPS parents said they fear their young children are losing their bilingualism — and worse, their cultural ties.

Simel Rodriguez, who immigrated to Boston from the Dominican Republic, has tried several times to get her daughter, a student at the Blackstone Elementary in the South End, a seat at the Hernández, only to wind up on a waiting list. Now her third-grader is losing her Spanish. On a recent trip to the Dominican, Rodriguez’s daughter isolated herself from her relatives because “she didn’t speak Spanish in a proper way,” Rodriguez said through an interpreter.

In October, BPS unveiled its latest strategy for educating its multilingual students as part of a deal with the state to avert a takeover of the district. The plan will place the vast majority of students learning English in full-immersion general education classes, regardless of English proficiency, where they will have access to multilingual services, but not instruction in their native language. The district’s announcement resulted in the resignation of nine of the 13 members of an expert task force charged with advising the School Committee on best practices for multilingual education.

District officials argued the new plan was consistent with feedback from the state Department of Elementary and Secondary Education after a routine probe by the agency found that many English learners in BPS do not have access to grade-level curriculum or the same kinds of learning opportunities as their English-speaking peers.

Latina mothers including Rodriguez pushed back against the plan for months, circulating petitions and forcing meetings with BPS and DESE officials. BPS has since announced plans to add new programs with native language instruction for recent migrants at four of its high schools, including the Muñiz, this fall. Its full-immersion plan for English Learners will gradually roll out, starting with the vast majority of kindergarteners in the fall.

“It’s frustrating,” said Cortiella, the former activist, “because the conditions that we had back then are the conditions we have here now.”

This story is part of a series produced by the Boston Globe’s Great Divide and Money, Power, Inequality teams. The Great Divide team explores educational inequality in Boston and statewide; Money, Power, Inequality covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporters: Mike Damiano, Christopher Huffaker, Mandy McLaren, Deanna Pan, Ivy Scott, Milton Valencia, Tiana Woodard

- Contributors: Niki Griswold, Lisa Wangsness, Marcela García, Adrian Walker

- Editors: Melissa Barragán Taboada, Kris Hooks

- Additional editors: Anica Butler, Cristina Silva, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Suzanne Kreiter, Jessica Rinaldi, Lane Turner, Craig F. Walker, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of Photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Video producers: Randy Vazquez, Olivia Yarvis

- Audio producers: Jesse Remedios, Scott Helman

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editors: Michael J. Bailey, Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Jenna Reyes, Adria Watson

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer, Adria Watson

- Homepage strategy: Peter Bailey-Wells

- Project lead: Melissa Barragán Taboada

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC