BROKEN PROMISES, UNFULFILLED HOPE

At Boston’s independent schools, parents offer their own solutions to city’s education gaps

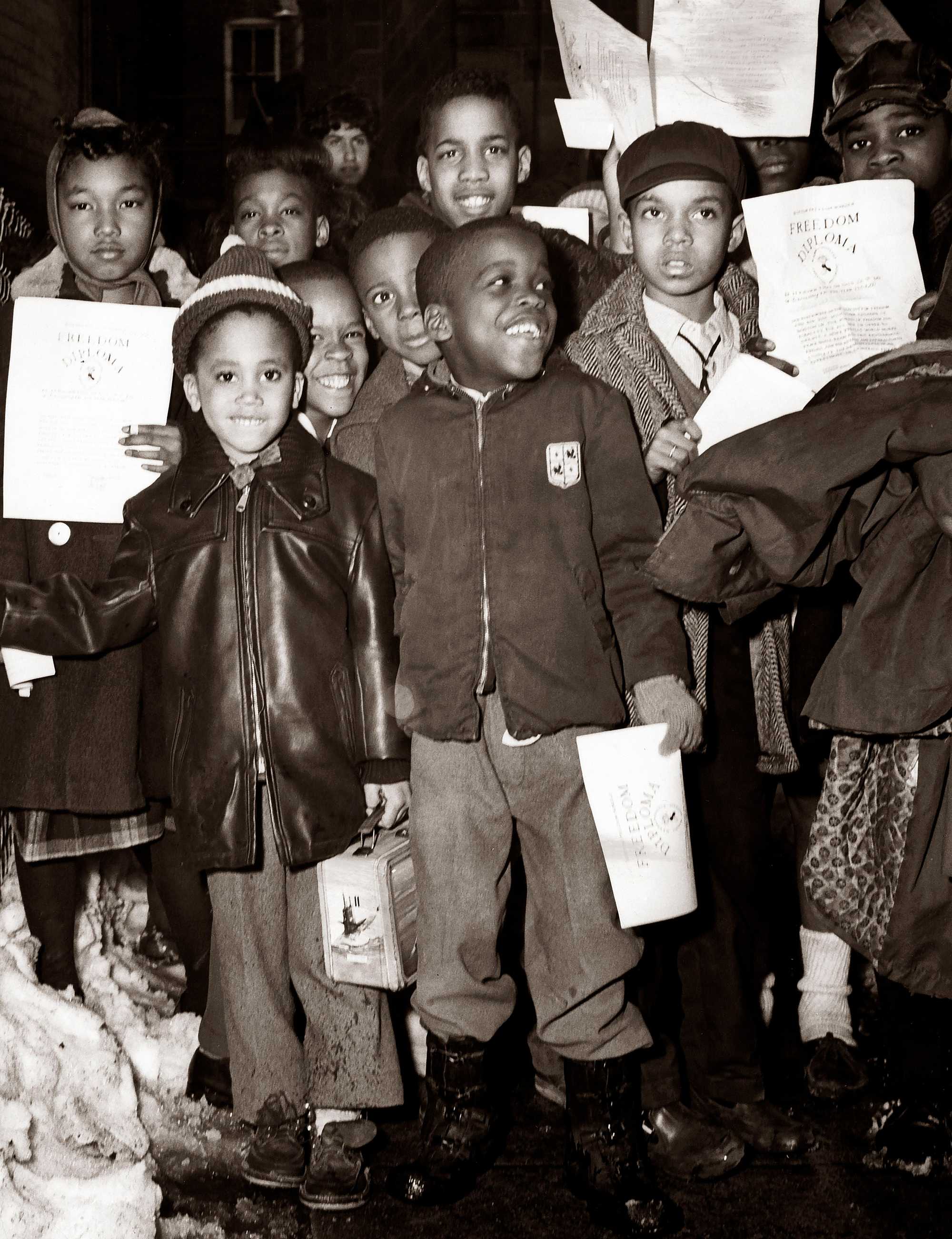

For one day in February 1964, the inside of St. Mark’s Social Center in Roxbury resembled something unheard of in Boston at the time — a fully integrated classroom. Black and white students sat side-by-side, shoulders colliding and knees brushing. The lessons of the day offered what didn’t make their public school textbooks: African American history, from the fight against segregation to cultural giants like Louis Armstrong, whose talents changed the world.

It was a flicker of revolution in a racially riven town. Across Boston’s Black neighborhoods, more than 30 pop-up schools like the one at St. Mark’s convened in churches, community centers, and nonprofits. As many as 10,000 students, many of whom were white and bused in from the suburbs, skipped class to show up at the schools as part of the Stay Out for Freedom protest of unequal and segregated education in Boston. The turnout had more than tripled from the year prior, when about 3,000 students attended the so-called Freedom Schools.

The Freedom Schools did not last long: only two days across the two years. But their legacy lives on in the idea that, if Black children are going to get the schooling they deserve, it might have to be in schools created and sustained by Black Bostonians. It was an independence movement born of necessity, one that predated and would outlast the landmark busing order of 1974.

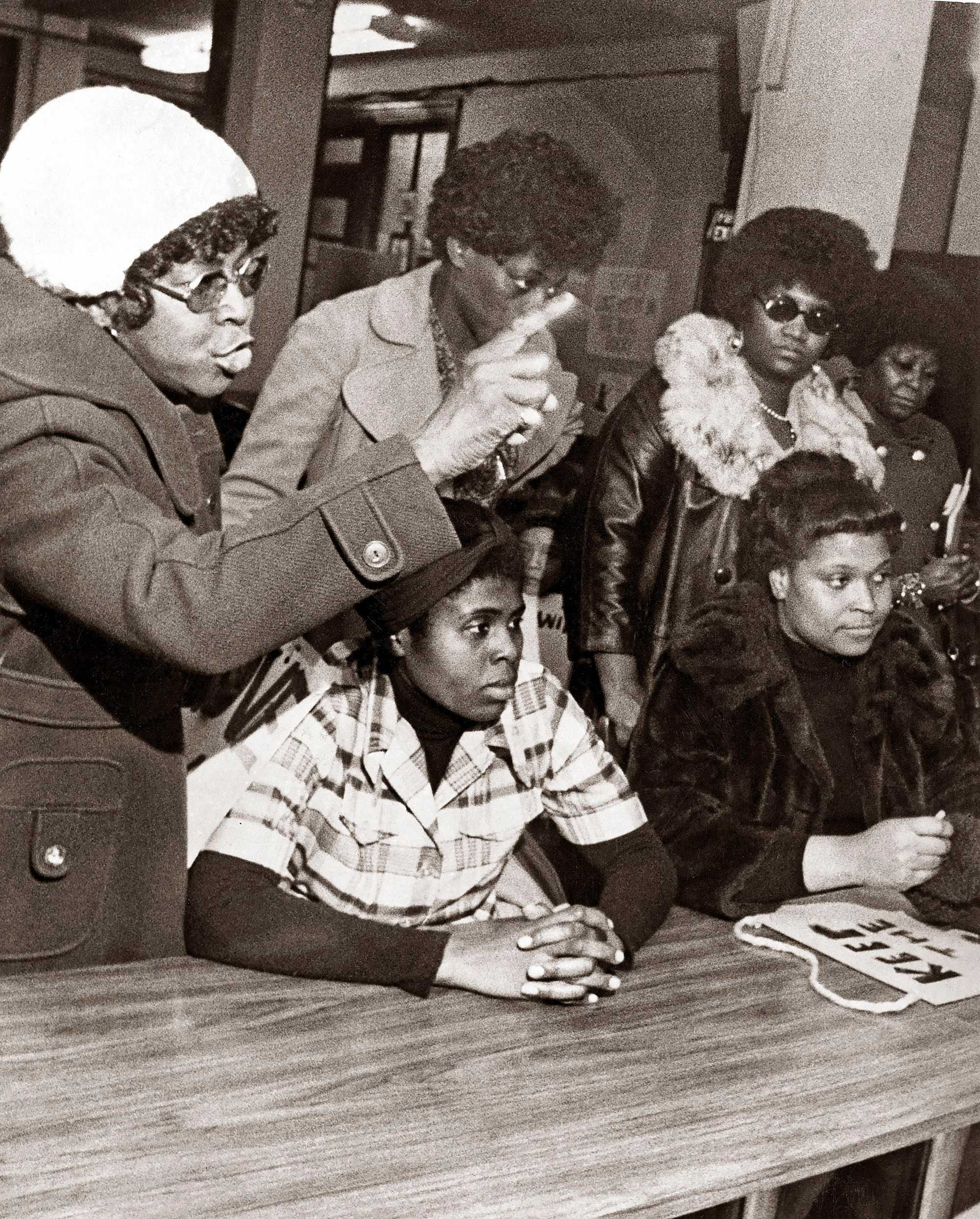

A discussion group circled up during a Freedom School event at St. Mark’s Social Center on Feb. 26, 1964. (Louis Russo/Globe Staff)

In the ‘60s and ‘70s, as Black Bostonians fought a civil rights battle for better education and as neighborhoods reeled from Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr.’s decision to integrate Boston’s public schools, the Roxbury Community School, Paige Academy, the Montessori Family Center, and the New School for Children opened as alternatives for Black students failed by BPS. Each institution was formed by residents — most often Black women — who had decided to take their children’s education into their own hands.

“When we look back at this history, we focus on the yellow school buses, white flight,” said former acting mayor Kim Janey, who attended the New School for Children in Roxbury during the early ‘70s. “But the story is the Black mothers and aunties and grandmothers who decided self-determination was the way to go, that we are going to create our own schools and educate our own kids.”

The pursuit of educational self-determination for Black families has a long history here.

Throughout the early 19th century, Black students were taught in the African Meeting House (now a historic landmark that houses the Museum of African American History) and later the Abiel Smith School, the first public school for Black children. At the time, the Boston School Committee sought to maintain a segregated system. Parents fought back, on the streets and in the courts, but were unsuccessful until 1855 when the state Legislature outlawed legal segregation in public schools.

In the 20th century, Boston saw institutions such as Otto and Muriel Snowden’s Freedom House, the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts, and several other community-run programs in Boston’s Black neighborhoods.

For Janey, the New School for Children, which opened in 1966, was like family. Her mom, Phyllis Janey, worked the front desk as a secretary. Her uncle served on the school board. And her aunt taught.

Class sizes were small, and all her teachers were Black. Among the teachers recruited to instruct New School’s pupils was Gloria Bourne Lee. The 20-something teacher, with the help of a teaching aide, led more than a dozen students through writing, arithmetic, and history. Curriculum builders infused lessons with Black leaders and historical figures.

Bourne Lee said she never designed her lessons with the intention of emphasizing Black pride or Black history. “It’s just who I was,” she said.

Janey attended school there 50 years ago — for kindergarten and first grade — so she doesn’t remember many details. But the feelings she experienced at the New School never left her.

“I’ve never felt as safe as I did then,” Janey recalled. “Feeling safe, feeling seen, feeling loved, feeling connected, and feeling valued.”

Wanting their son to have a similar educational experience, Sister Angela and Brother Joe Cook transformed their theater company into Paige Academy, a small independent school in Roxbury, in 1975. To get their vision off the ground, the young couple would walk to closing BPS schools in the neighborhood and bring the left-behind desks, chairs, and school supplies back with them.

Advertisement

Nearly 50 years later, Paige Academy has grown from a makeshift classroom of hand-me-down desks and supplies to a self-sufficient community school. Families can enroll by paying tuition or enrolling for free through the city’s universal pre-K program.

Today, about 100 children up to sixth grade are provided year-round programming. Almost all of the students are kids of color, and most of the teachers are people of color, many of whom attended the academy themselves. The school’s curriculum focuses on the seven principles of Kwanzaa.

“We really just spent time observing the kids and seeing what they needed, and then try to provide it to them,” Angela Cook said.

In one classroom on a recent morning, more than a dozen students closed their eyes, crossed their legs, connected their thumbs and middle fingers as their teacher led them in meditation. In a second classroom, Joe Cook helped one student operate a small robot with a tablet. In a third classroom downstairs, a circle of toddlers engaged in a musical math lesson, counting out each slam of their tiny hands against a cacophonous symphony of Djembe drums.

Shanta Williams, whose preschooler Jaxon attends Paige Academy, said she has seen a difference in his early education compared with her three older children, who attended public schools in New York and Boston. They were always stressed, she said, but Jaxon is more carefree.

“People feel more comfortable when their environment is more cultural,” Williams said. At Paige, “he can find his own identity.”

Newer schools, such as Roxbury Roots Montessori school that opened in 2021, have also been shaped by the desire for more culturally sensitive learning.

Roxbury Roots is small: only 24 students between ages 3 and 6, three full-time staff, two part-timers, and one volunteer.

Its founder Renee Jolley follows the example set by local educators such as Mae Arlene Gadpaille of Roxbury, who in the ‘60s opened the small Montessori Family Center to educate neighborhood teens, and made it her life mission to open a site that met the basic necessities for entire families, ranging from employment to groceries to housing.

Like the family center, Roxbury Roots emphasizes Montessori education principles — independence, hands-on activity, and go-at-your-own pace learning.

And Jolley’s creation doesn’t look like a traditional school. It looks like a home.

Advertisement

Despite the work these schools have done over the years, their creators agree that they find themselves in a sort of inescapable time loop, fighting against the same educational injustices their predecessors sought to erase.

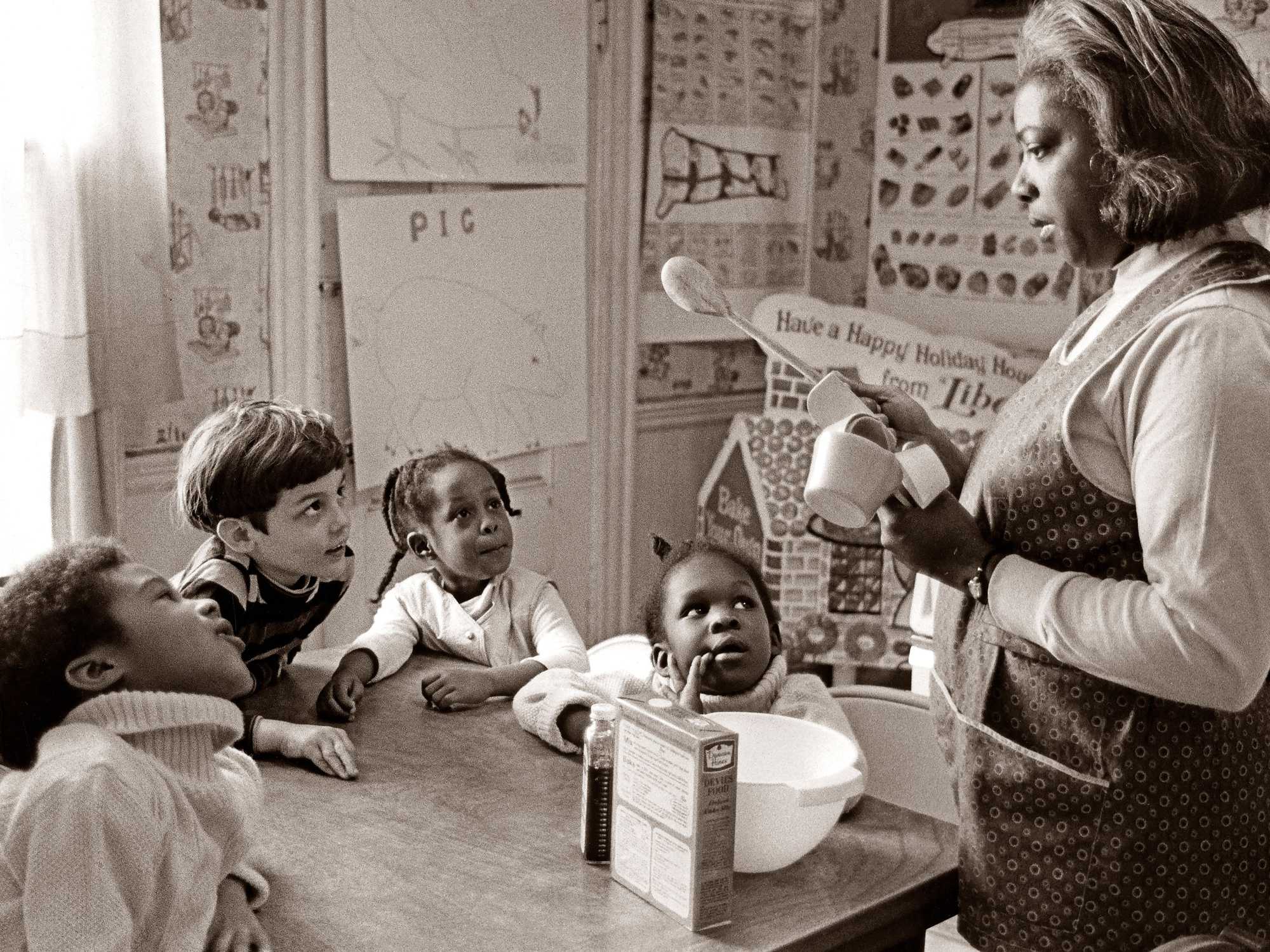

At left, students painted together at the Roxbury Community School in 1966. Cecilia Washington, Roxbury Community School dietician and chief cook, gave a group of students a cooking demonstration in 1969. (Charles Dixon, Gil Friedberg/Globe Staff)

For myriad reasons, the schools hardly make a dent in local educational inequality. They are small and many are short-lived. They don’t have the tax dollars of public schools to spend or the steep tuitions from which more affluent, whiter private schools benefit. When community funding runs dry, the schools must close.

Some independent schools, however, such as the Epiphany School in Dorchester’s Shawmut neighborhood, have withstood those blows. Founded in 1998, by the Rev. John Finley IV, an associate priest at the St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, the school relies primarily on donors and foundations for funding. It is also affiliated with the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts.

Epiphany School provides full scholarships for its middle schoolers, all of whom are enrolled through either referral or a lottery process and are at or below the federal poverty level. It feeds students and staff breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Some of the school’s 65 staff live at school-owned housing free-of-charge, and just a few paces away.

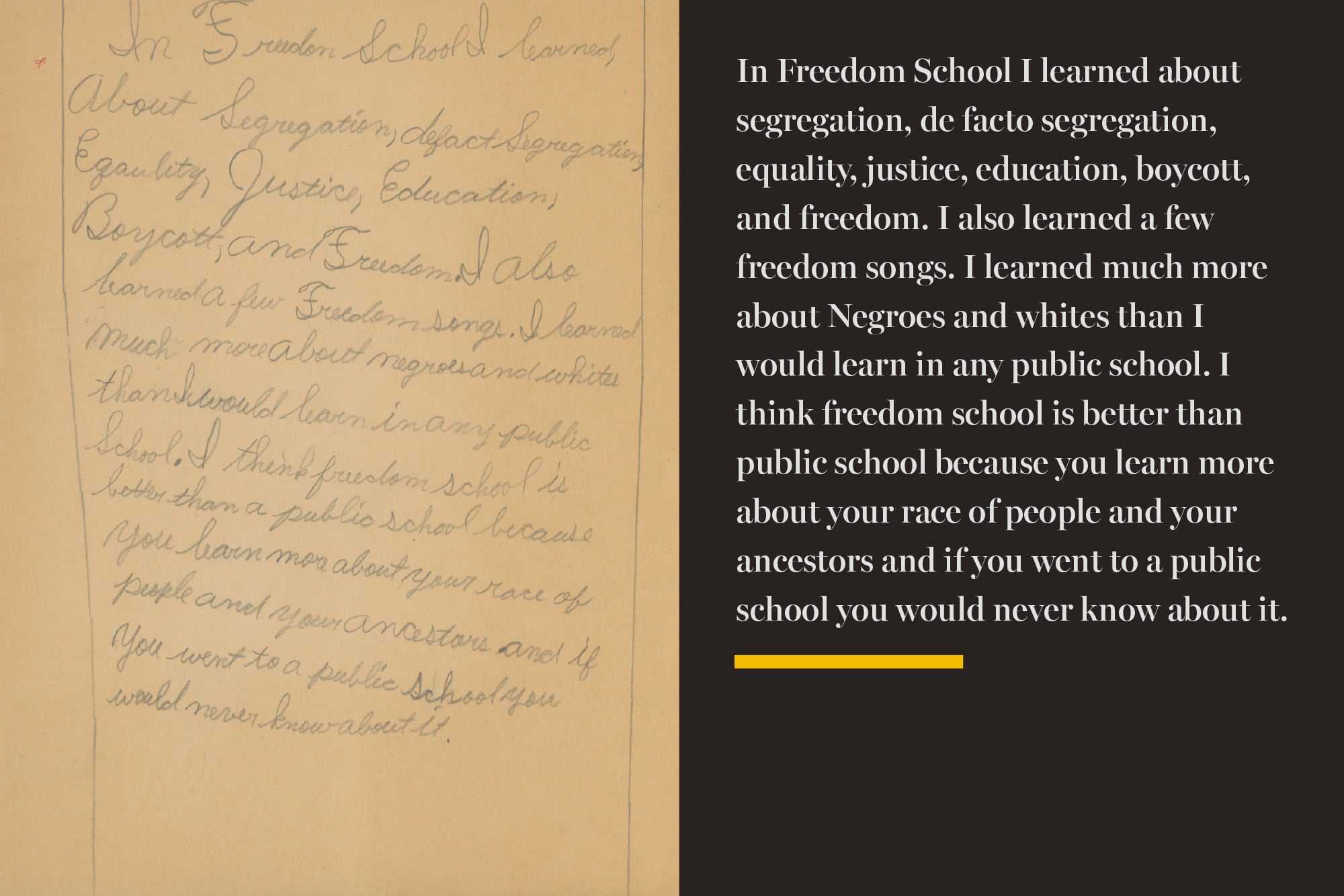

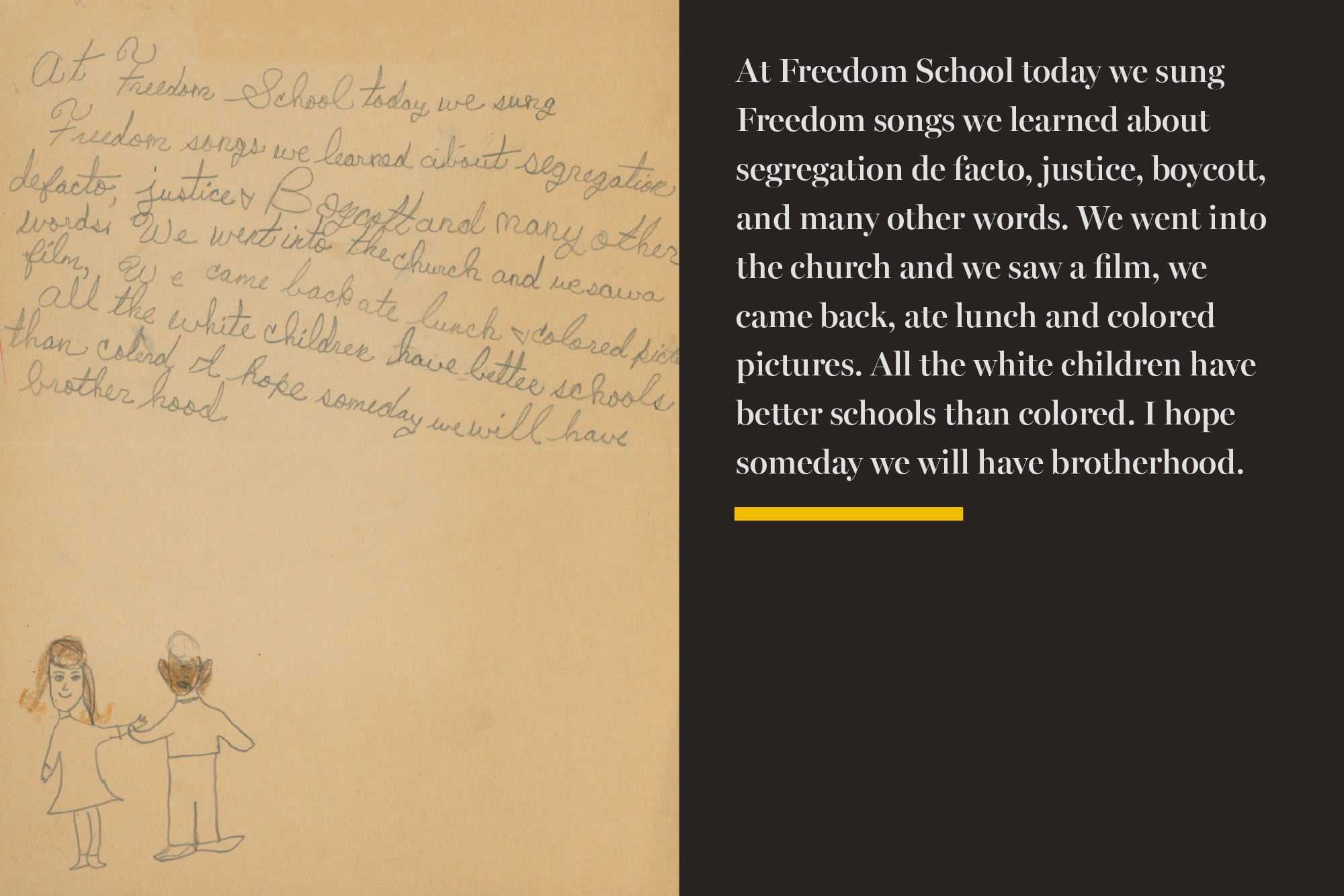

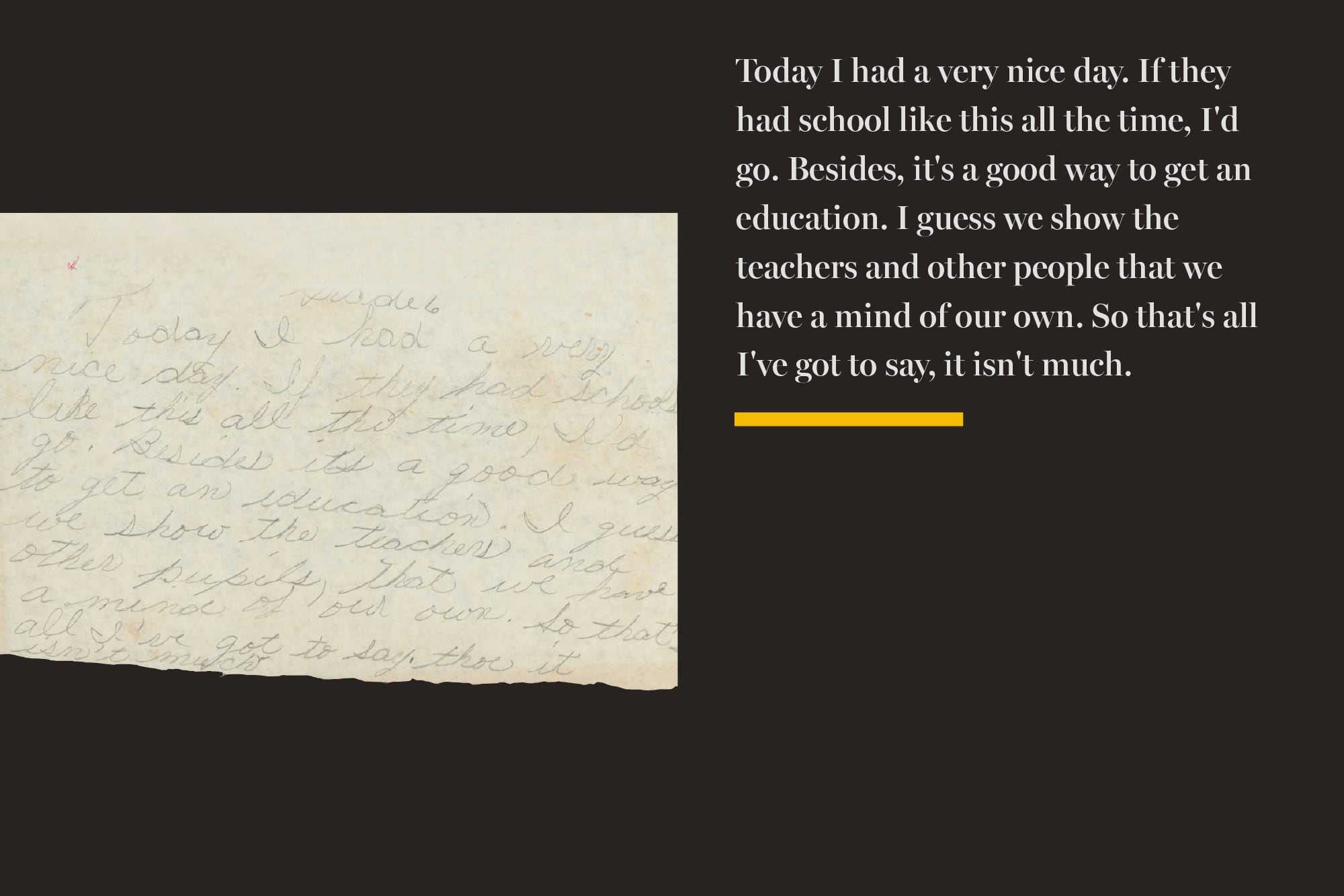

Read letters from students who attended Freedom Schools

![One student preferred the day of education over their usual public school experience: “I wish that we could go to freedom school every single day, but it wouldn’t be fare [sic] to our [Freedom School] teachers... I hope that I will meet up with them again!” (Charles Glenn papers at Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections)](/metro/2024/06/busing-in-boston/static/0d870a1231eb7c37a6820ad94cc19366/8f95c/N6JGWJUIGNHX5EBNF3HXK7WSJE.jpg)

![In this handwritten letter, one participant decried Boston’s unequal education, and the affect it has on everyone. “People don’t realize they are hurting the leaders of tomorrow, in there [sic] school work, in social life, and in living condition [sic],” she wrote. (Charles Glenn papers at Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections)](/metro/2024/06/busing-in-boston/static/71d7b08089c59bef605baf74a3461e6a/8f95c/OEMPFAIF7ZAE3HQUMAG3CZ2Y5A.jpg)

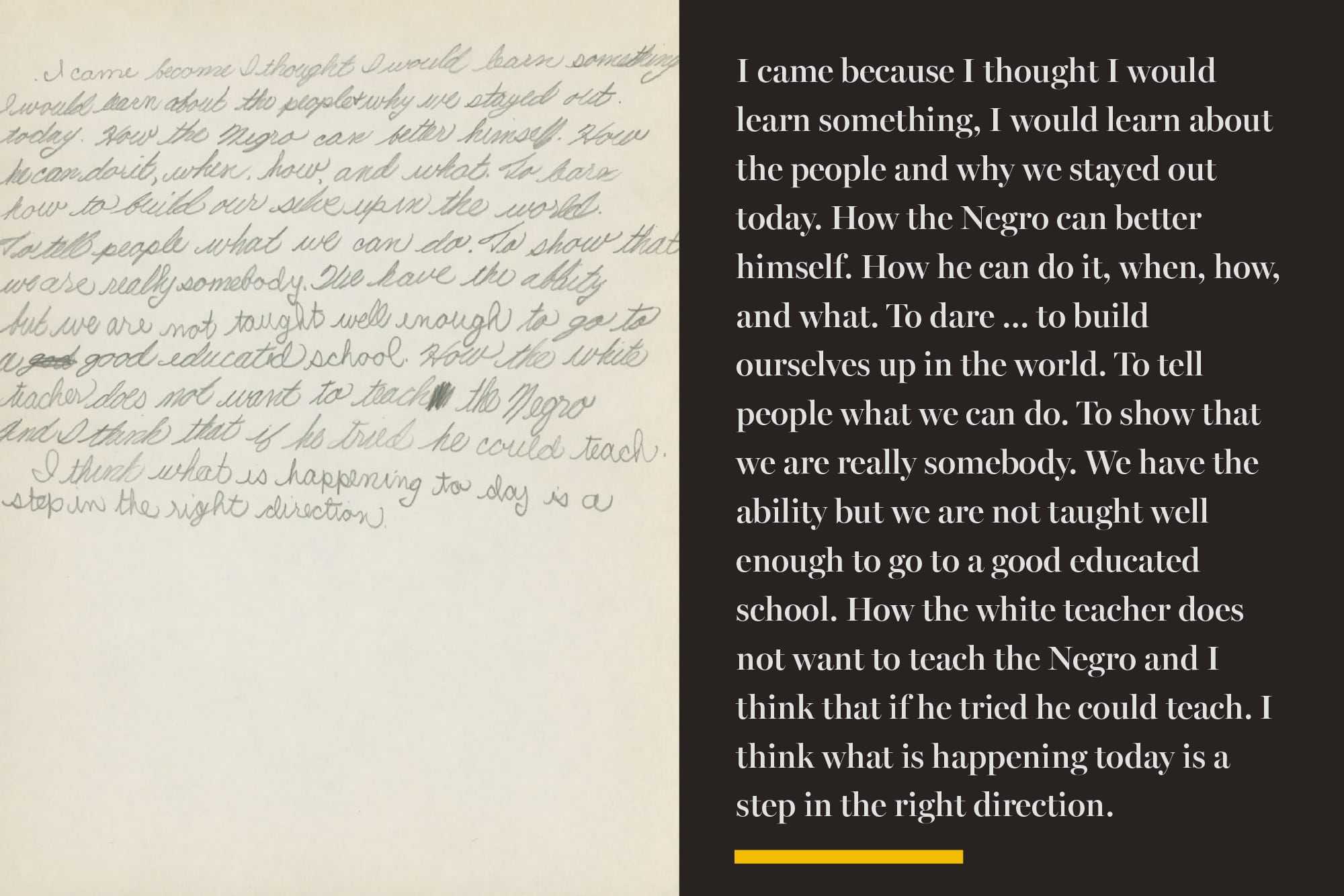

An attendee acknowledged the substandard quality of education in Black public schools, but recognizes the massive potential of her community: “We are really somebody. We have the ability but we are not taught well enough to go to a good educated school.” (Charles Glenn papers at Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections)

There are no waitlists, because hardly anyone leaves and creating one would give a “false hope” for interested families, said Finley, the head of school.

“I don’t think every school has to be the same as us at all,” said Finley, who is white. “But I do think that Epiphany is a good example of what we could hope for for every child.”

On a recent Thursday morning, about 20 sixth-graders were seated at their desks, arranged in groups of four. A Black male teacher led them through a lesson on prose. A plush sectional and synthetic succulents offered a safe space away from the stresses of classroom learning. The school serves as a space where the needs of Black children are met.

“The way I think about it — our kids, when they leave us, will not be the most important people in their new school. The school won’t be set up just for them,” Finley said. “But for five years, four years, whatever number of years they’re here, everything is set up for them.”

This story is part of a series produced by the Boston Globe’s Great Divide and Money, Power, Inequality teams. The Great Divide explores educational inequality in Boston and statewide; Money, Power, Inequality covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporters: Mike Damiano, Christopher Huffaker, Mandy McLaren, Deanna Pan, Ivy Scott, Milton Valencia, Tiana Woodard

- Contributors: Niki Griswold, Lisa Wangsness, Marcela García, Adrian Walker

- Editors: Melissa Barragán Taboada, Kris Hooks

- Additional editors: Anica Butler, Cristina Silva, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Suzanne Kreiter, Jessica Rinaldi, Lane Turner, Craig F. Walker, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of Photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Video producers: Randy Vazquez, Olivia Yarvis

- Audio producers: Jesse Remedios, Scott Helman

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editors: Michael J. Bailey, Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Jenna Reyes, Adria Watson

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer, Adria Watson

- Homepage strategy: Peter Bailey-Wells

- Project lead: Melissa Barragán Taboada

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC