BROKEN PROMISES, UNFULFILLED HOPE

What led to Boston’s busing crisis? This graphic novel explains.

In 1855, Massachusetts became the first state to abolish segregating public schools on the basis of skin color or race. But 100 years later, Boston’s Black and white students still largely attended separate schools. That’s because Boston’s neighborhoods were segregated due to discriminatory housing policies, like redlining, and students were assigned to schools close to their homes.

In 1855, Massachusetts became the first state to abolish segregating public schools on the basis of skin color or race. But 100 years later, Boston’s Black and white students still largely attended separate schools. That’s because Boston’s neighborhoods were segregated due to discriminatory housing policies, like redlining, and students were assigned to schools close to their homes.

In 1855, Massachusetts became the first state to abolish segregating public schools on the basis of skin color or race. But 100 years later, Boston’s Black and white students still largely attended separate schools. That’s because Boston’s neighborhoods were segregated due to discriminatory housing policies, like redlining, and students were assigned to schools close to their homes.

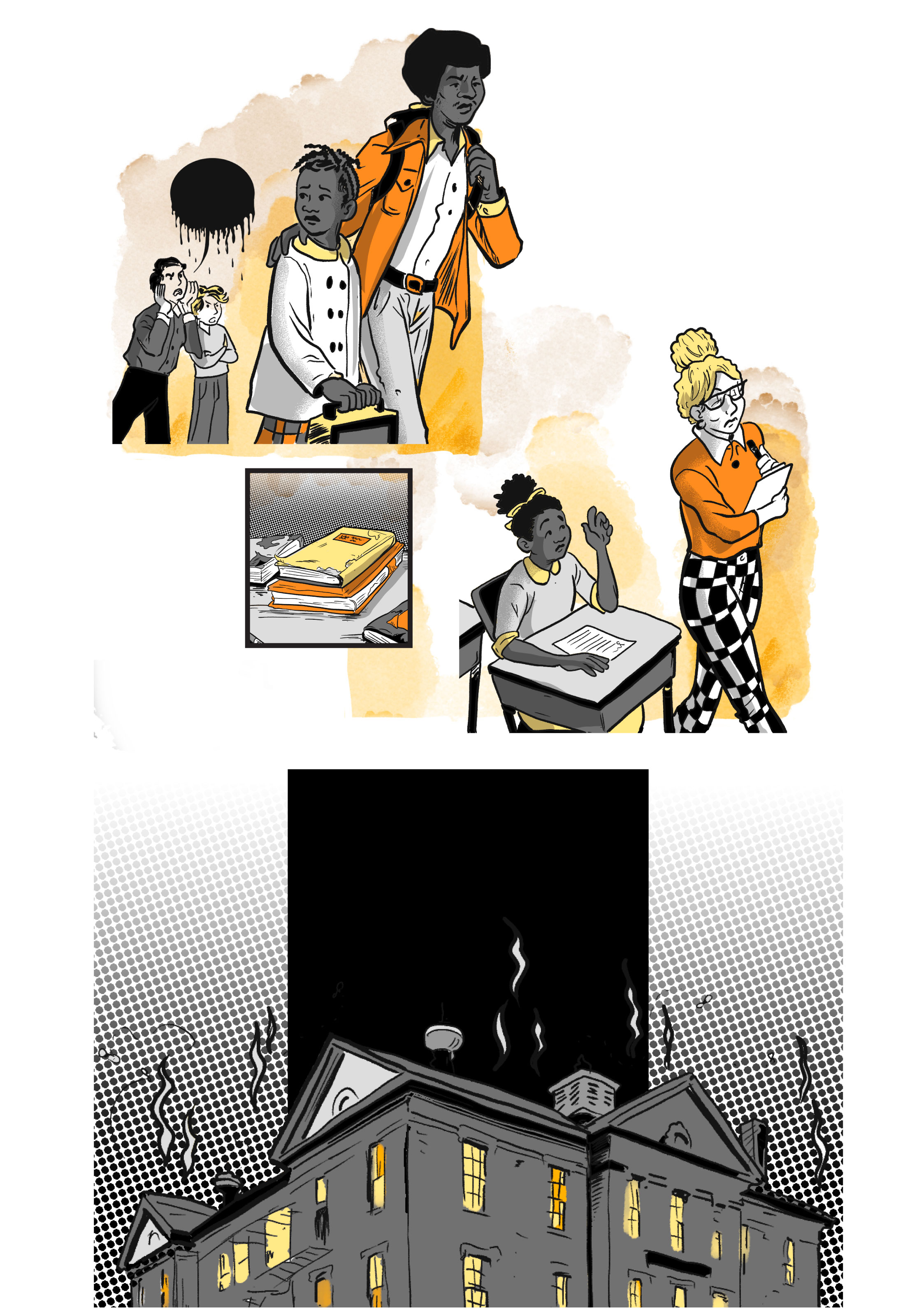

Schools in Boston’s Black neighborhoods in the 1960s were underfunded, under-resourced, and oftentimes staffed by unqualified teachers who disrespected parents and students.

Schools in Boston’s Black neighborhoods were also falling apart. The Sherwin School in Roxbury reportedly reeked of a stench so strong, parents and children could smell it from the playground across the street.

Schools in Boston’s Black neighborhoods in the 1960s were underfunded, under-resourced, and oftentimes staffed by unqualified teachers who disrespected parents and students.

Schools in Boston’s Black neighborhoods were also falling apart. The Sherwin School in Roxbury reportedly reeked of a stench so strong, parents and children could smell it from the playground across the street.

Schools in Boston’s Black neighborhoods in the 1960s were underfunded, under-resourced, and oftentimes staffed by unqualified teachers who disrespected parents and students.

Schools in Boston’s Black neighborhoods were also falling apart. The Sherwin School in Roxbury reportedly reeked of a stench so strong, parents and children could smell it from the playground across the street.

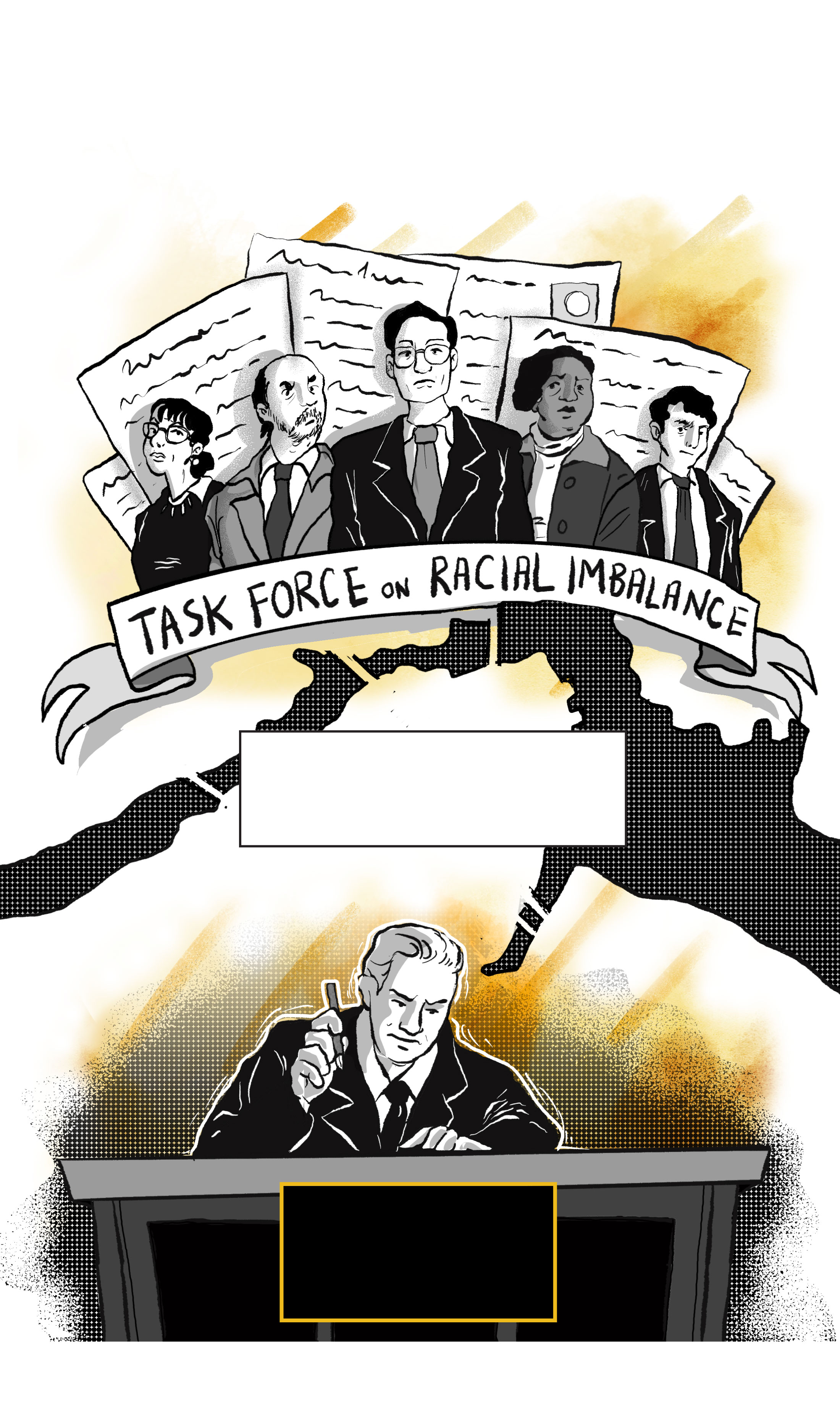

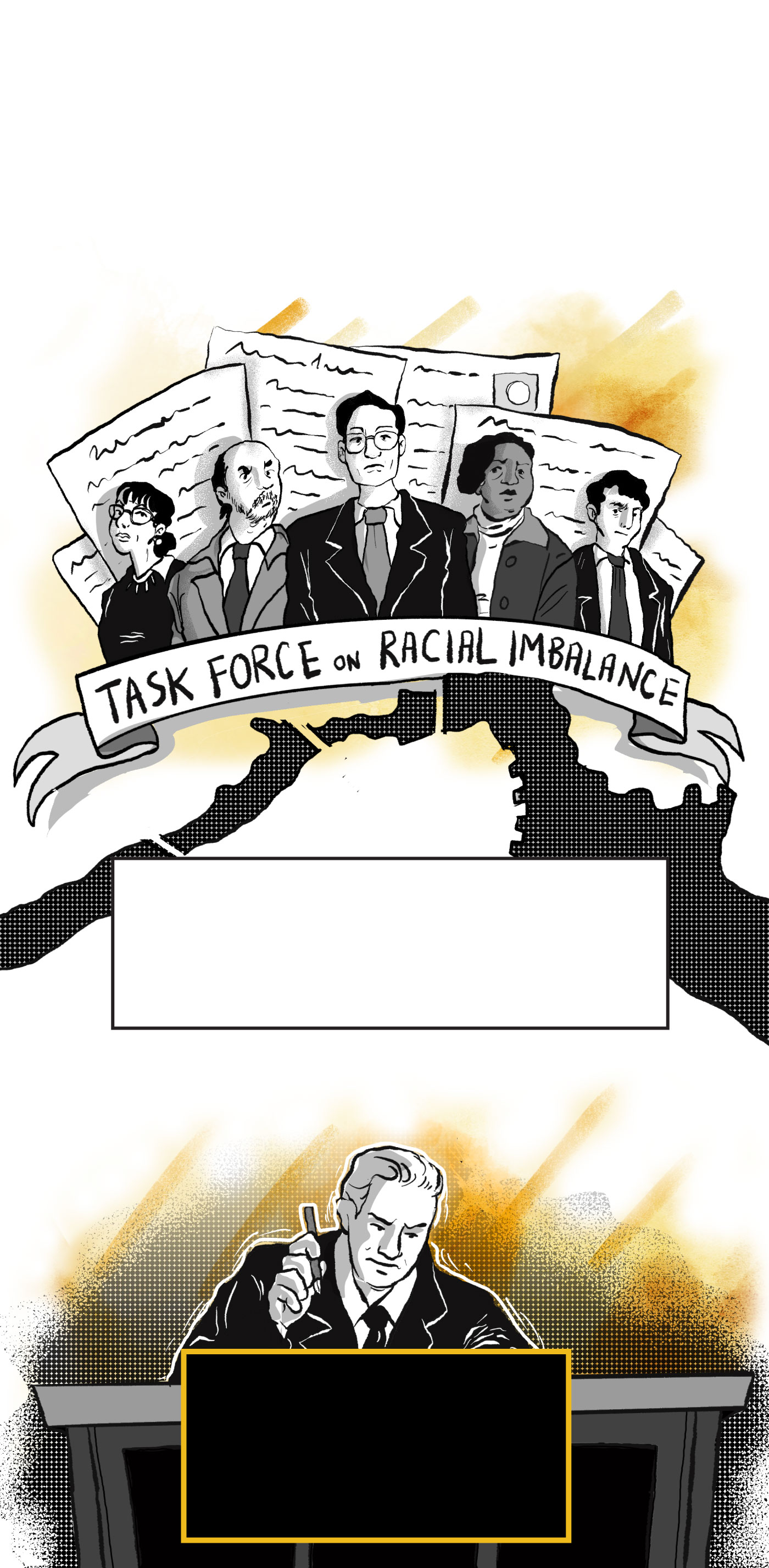

The Boston Chapter of the NAACP wanted the School Committee to acknowledge the pernicious effects of de facto segregation on the city’s schools. A groundbreaking 1965 report by the state Board of Education’s Task Force on Racial Imbalance showed school segregation was hurting Black and white students alike. Segregated schools also encouraged prejudice among all children, regardless of race.

“It is imperative that we begin to end this harmful system of separation,” the report concluded. “The means are at hand. Each day of delay is a day of damage to the children of our Commonwealth.”

That year, Governor John Volpe signed the Racial Imbalance Act into law, requiring public school districts to integrate or risk losing state funds.

The Boston Chapter of the NAACP wanted the School Committee to acknowledge the pernicious effects of de facto segregation on the city’s schools. A groundbreaking 1965 report by the state Board of Education’s Task Force on Racial Imbalance showed school segregation was hurting Black and white students alike. Segregated schools also encouraged prejudice among all children, regardless of race.

“It is imperative that we begin to end this harmful system of separation,” the report concluded. “The means are at hand. Each day of delay is a day of damage to the children of our Commonwealth.”

That year, Governor John Volpe signed the Racial Imbalance Act into law, requiring public school districts to integrate or risk losing state funds.

The Boston Chapter of the NAACP wanted the School Committee to acknowledge the pernicious effects of de facto segregation on the city’s schools. A groundbreaking 1965 report by the state Board of Education’s Task Force on Racial Imbalance showed school segregation was hurting Black and white students alike. Segregated schools also encouraged prejudice among all children, regardless of race.

“It is imperative that we begin to end this harmful system of separation,” the report concluded. “The means are at hand. Each day of delay is a day of damage to the children of our Commonwealth.”

That year, Governor John Volpe signed the Racial Imbalance Act into law, requiring public school districts to integrate or risk losing state funds.

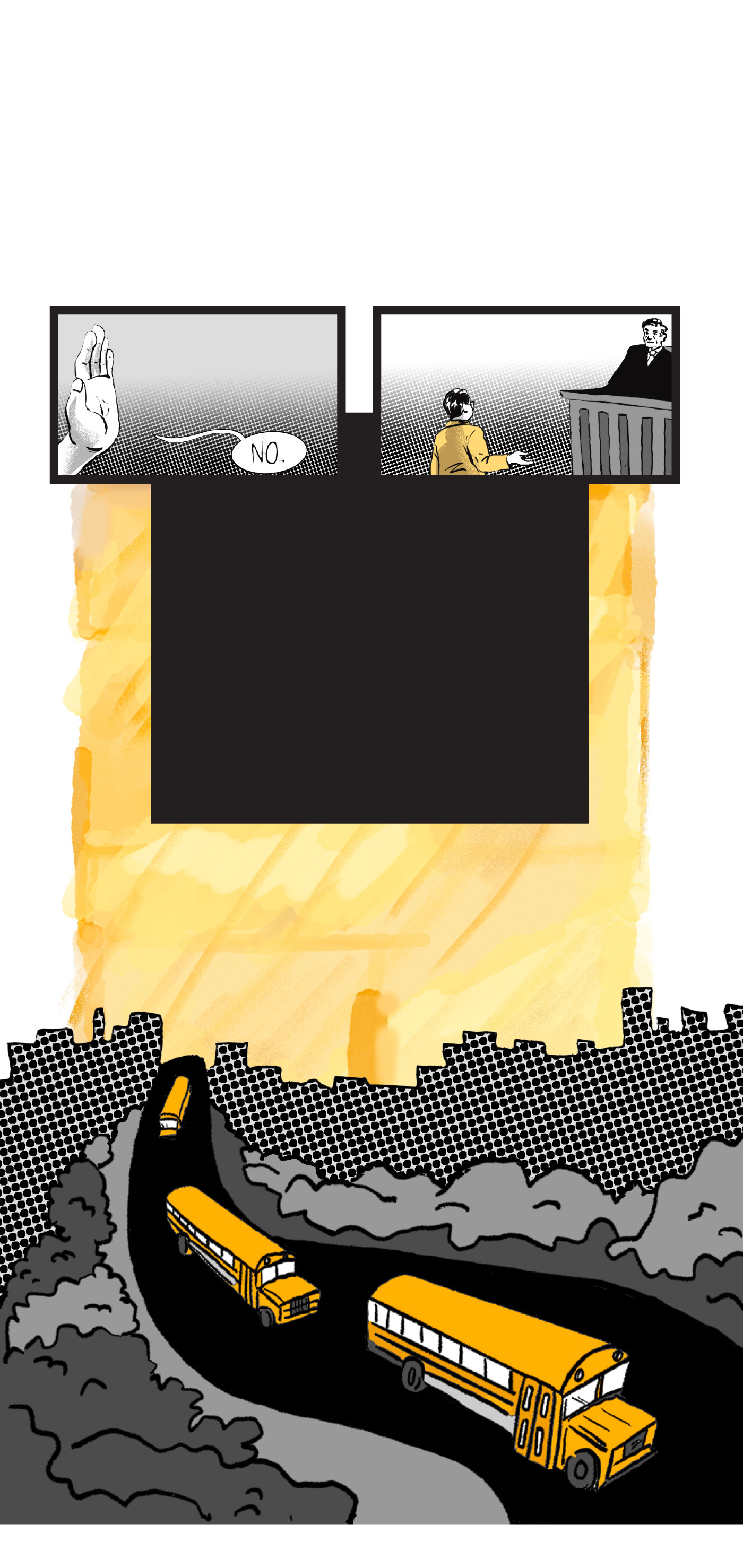

Despite years of protests and calls for change, the Boston School Committee resisted reforms that would integrate the city’s schools. The School Committee’s most vocal opponent of forced integration was Louise Day Hicks, a white woman from South Boston who served as its chairwoman from 1963 to 1965, and who favored neighborhood schools and denied de facto segregation was a problem.

The state Board of Education rejected the School Committee's plan to eliminate segregation. Instead, the School Committee tried suing to get the Racial Imbalance Act overturned. In the meantime, Black students began fleeing Boston Public Schools in pursuit of a better education at nearby suburban schools through the Metco program.

Despite years of protests and calls for change, the Boston School Committee resisted reforms that would integrate the city’s schools. The School Committee’s most vocal opponent of forced integration was Louise Day Hicks, a white woman from South Boston who served as its chairwoman from 1963 to 1965, and who favored neighborhood schools and denied de facto segregation was a problem.

The state Board of Education rejected the School Committee's plan to eliminate segregation. Instead, the School Committee tried suing to get the Racial Imbalance Act overturned. In the meantime, Black students began fleeing Boston Public Schools in pursuit of a better education at nearby suburban schools through the Metco program.

Despite years of protests and calls for change, the Boston School Committee resisted reforms that would integrate the city’s schools. The School Committee’s most vocal opponent of forced integration was Louise Day Hicks, a white woman from South Boston who served as its chairwoman from 1963 to 1965, and who favored neighborhood schools and denied de facto segregation was a problem.

The state Board of Education rejected the School Committee's plan to eliminate segregation. Instead, the School Committee tried suing to get the Racial Imbalance Act overturned. In the meantime, Black students began fleeing Boston Public Schools in pursuit of a better education at nearby suburban schools through the Metco program.

Advertisement

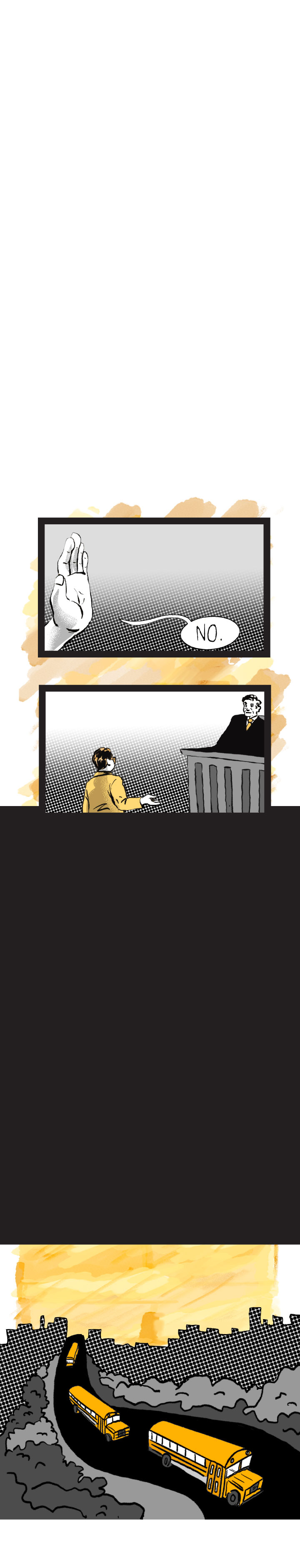

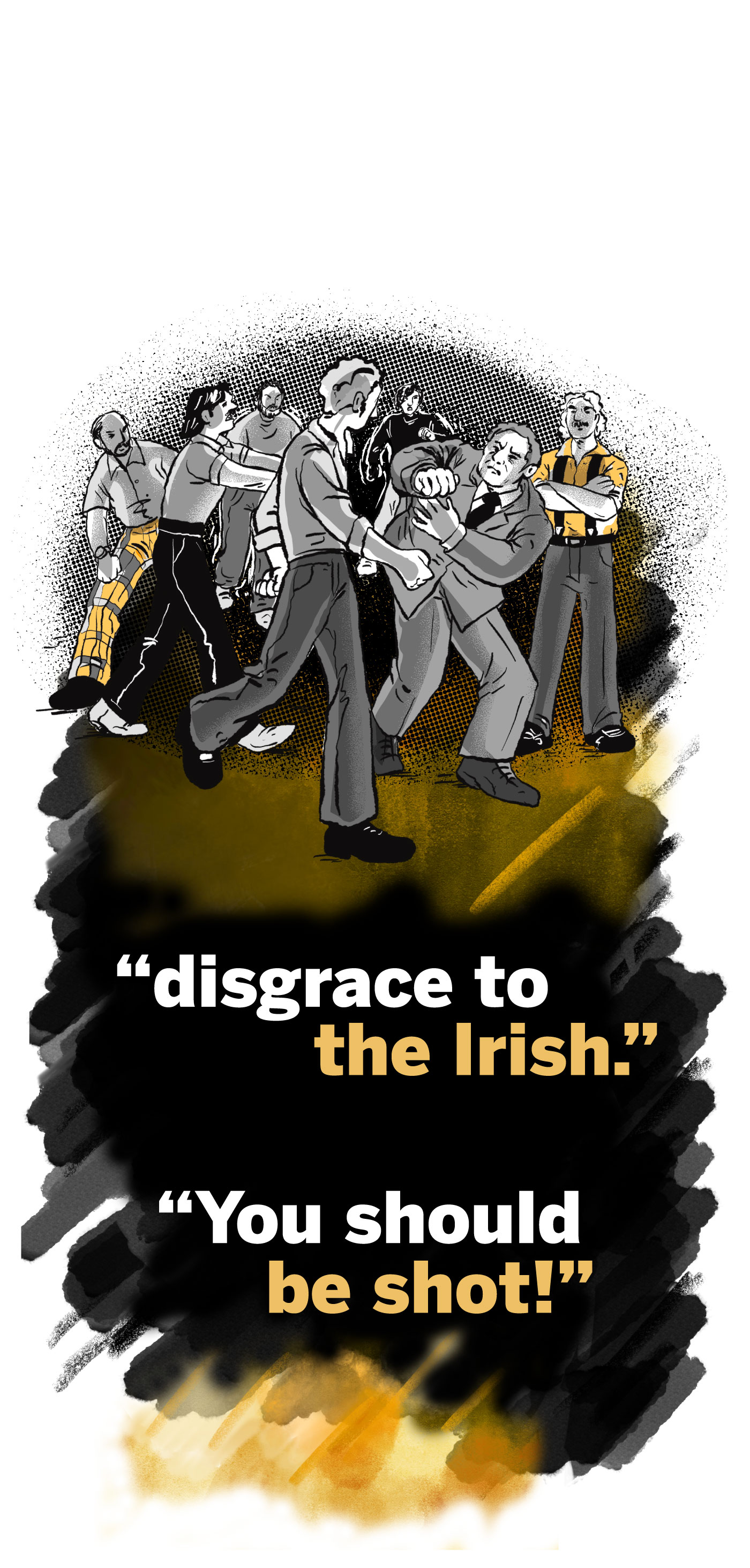

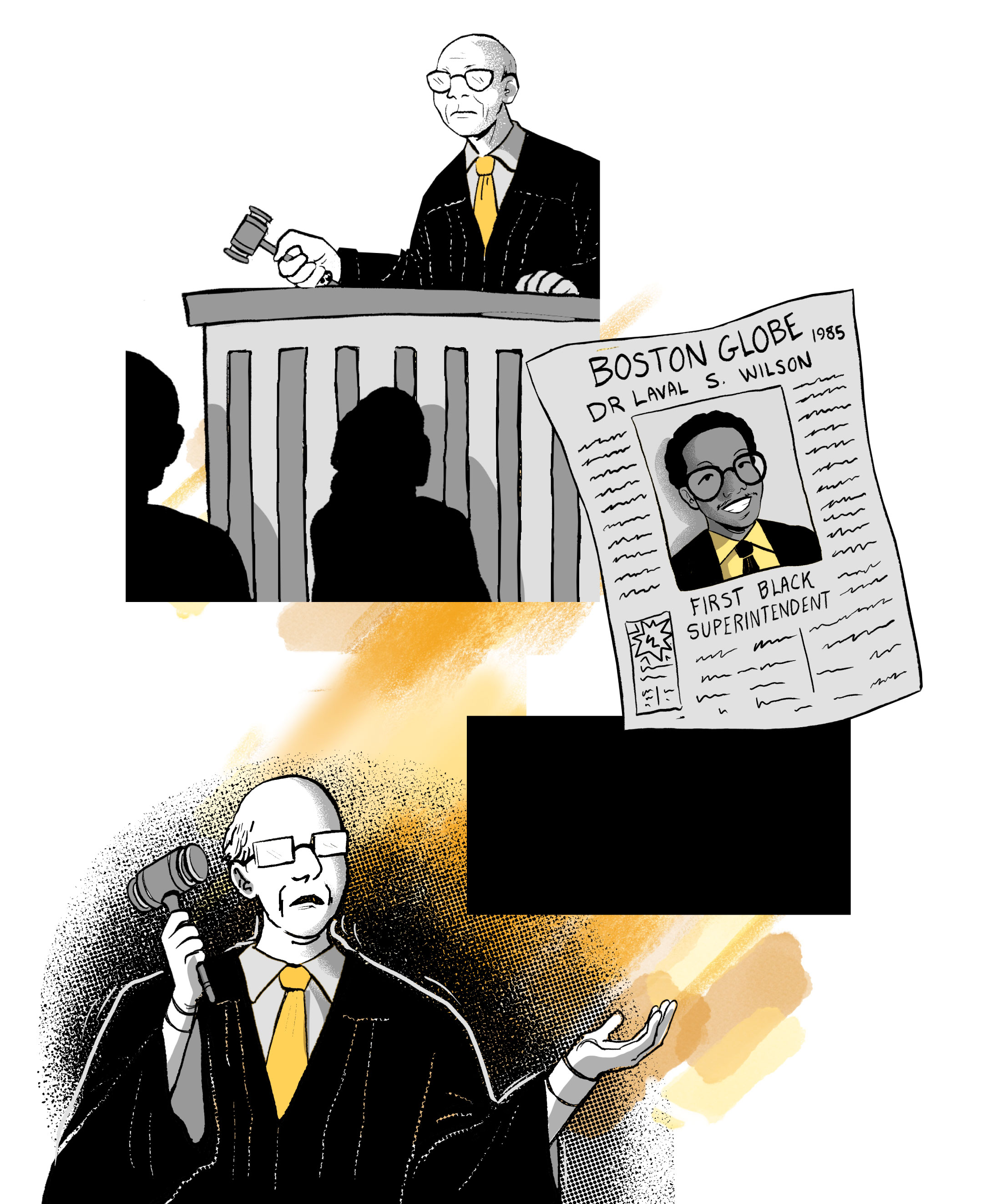

On March 15, 1972, the Boston NAACP filed a class-action suit, Morgan v. Hennigan, in federal court on behalf of 14 parents and 43 children. Tallulah Morgan, a young mother of three, was the lead plaintiff. The plaintiffs argued the city’s schools were deliberately and unconstitutionally segregated.

Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. ruled in favor of the plaintiffs two years later on June 21, 1974, writing in his decision that BPS had “intentionally brought about and maintained a dual school system.” He ordered the School Committee to come up with its own plan for integrating the schools.

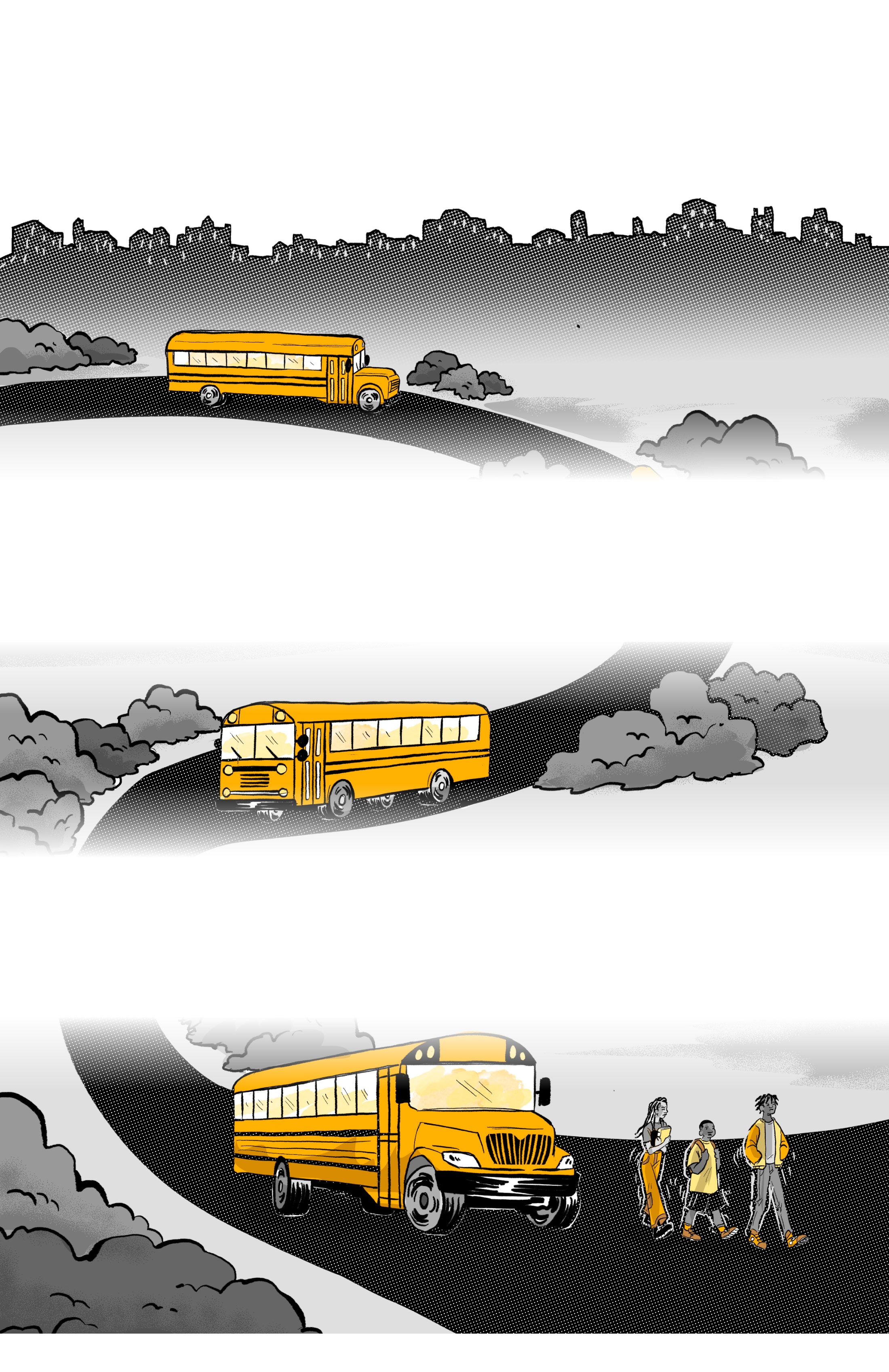

Until then, thousands of Black and white students would be bused to schools outside their neighborhoods in the fall…

On March 15, 1972, the Boston NAACP filed a class-action suit, Morgan v. Hennigan, in federal court on behalf of 14 parents and 43 children. Tallulah Morgan, a young mother of three, was the lead plaintiff. The plaintiffs argued the city’s schools were deliberately and unconstitutionally segregated.

Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. ruled in favor of the plaintiffs two years later on June 21, 1974, writing in his decision that BPS had “intentionally brought about and maintained a dual school system.” He ordered the School Committee to come up with its own plan for integrating the schools.

Until then, thousands of Black and white students would be bused to schools outside their neighborhoods in the fall…

On March 15, 1972, the Boston NAACP filed a class-action suit, Morgan v. Hennigan, in federal court on behalf of 14 parents and 43 children. Tallulah Morgan, a young mother of three, was the lead plaintiff. The plaintiffs argued the city’s schools were deliberately and unconstitutionally segregated.

Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. ruled in favor of the plaintiffs two years later on June 21, 1974, writing in his decision that BPS had “intentionally brought about and maintained a dual school system.” He ordered the School Committee to come up with its own plan for integrating the schools.

Until then, thousands of Black and white students would be bused to schools outside their neighborhoods in the fall…

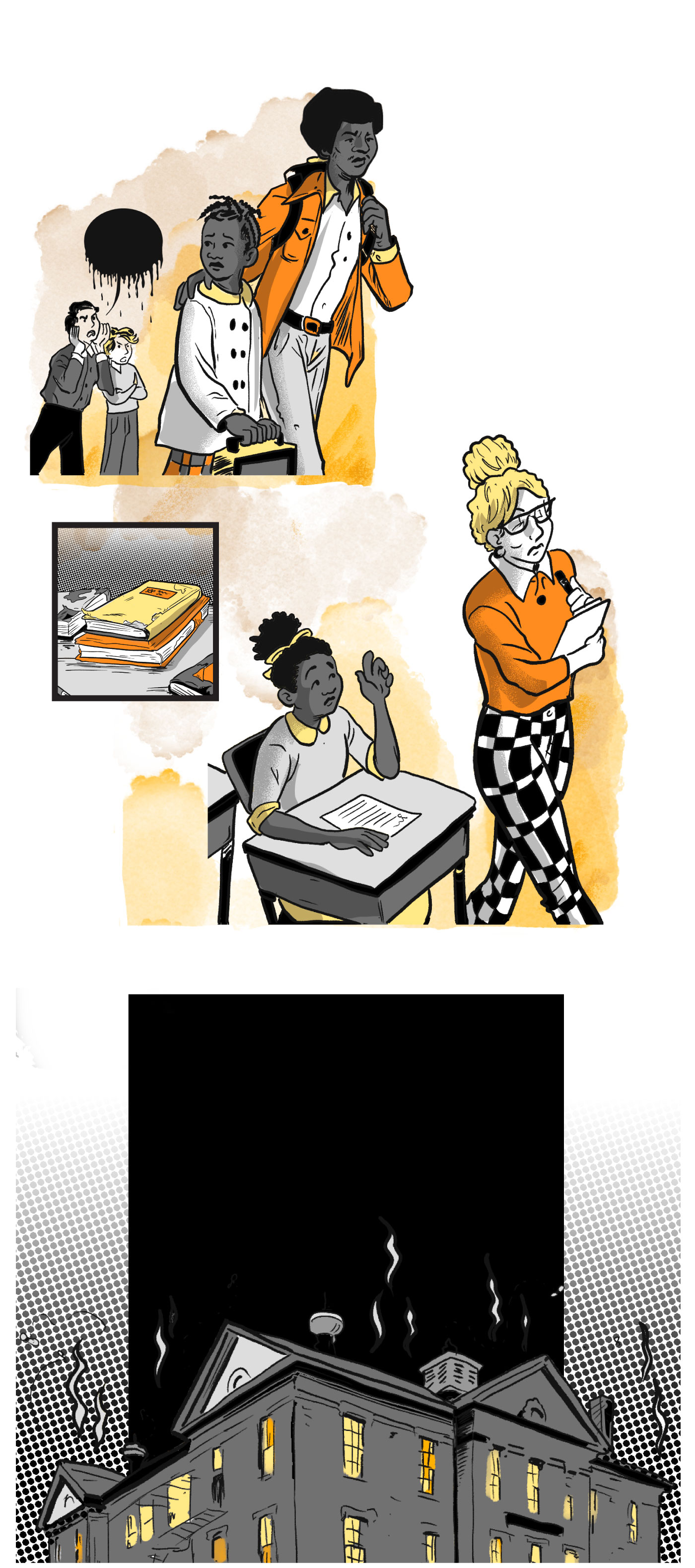

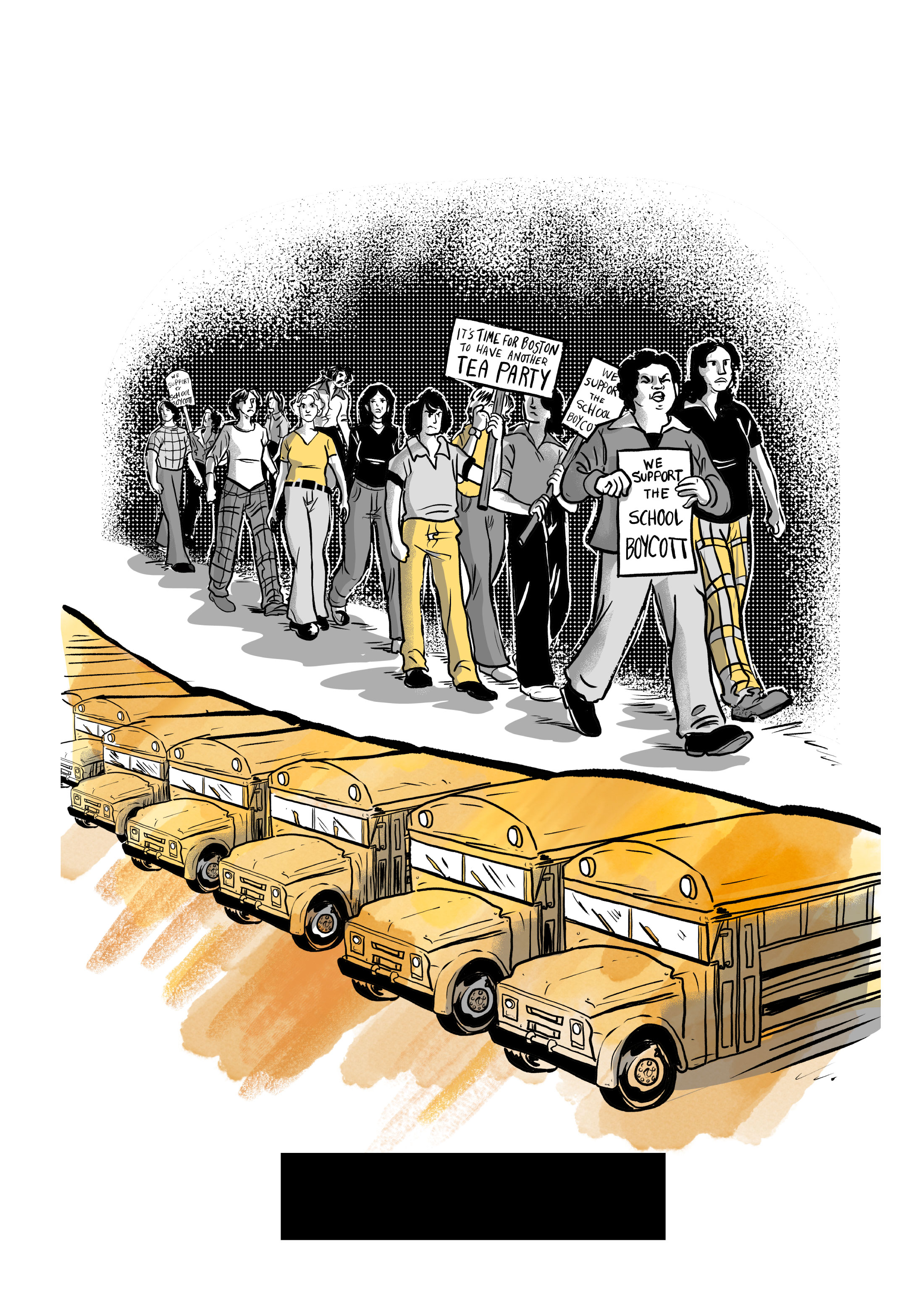

That summer, hundreds of white parents began organizing anti-busing schoolwide boycotts. Some even tried raising money to start an alternative school system.

Resistance to Garrity’s plan would only get worse as the start of the new school year drew closer…

That summer, hundreds of white parents began organizing anti-busing schoolwide boycotts. Some even tried raising money to start an alternative school system.

Resistance to Garrity’s plan would only get worse as the start of the new school year drew closer…

That summer, hundreds of white parents began organizing anti-busing schoolwide boycotts. Some even tried raising money to start an alternative school system.

Resistance to Garrity’s plan would only get worse as the start of the new school year drew closer…

On Sept. 3, 1974, a white youth threatened a Black history teacher assigned to historically white South Boston High School with a pellet gun to his head.

Another Black teacher assigned to South Boston High got his car windows smashed in.

On Sept. 3, 1974, a white youth threatened a Black history teacher assigned to historically white South Boston High School with a pellet gun to his head.

Another Black teacher assigned to South Boston High got his car windows smashed in.

On Sept. 3, 1974, a white youth threatened a Black history teacher assigned to historically white South Boston High School with a pellet gun to his head.

Another Black teacher assigned to South Boston High got his car windows smashed in.

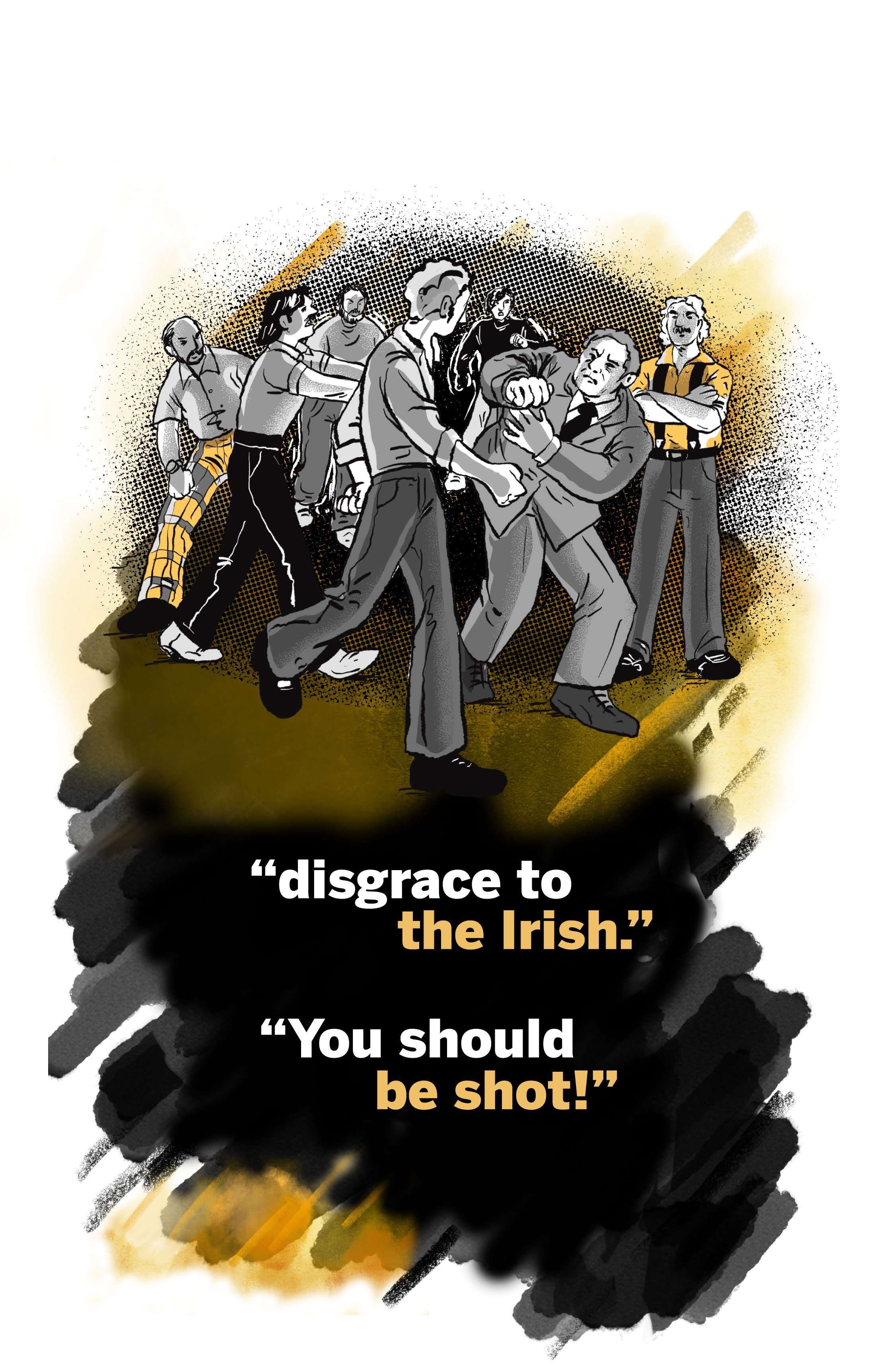

Days before the start of the new school year, the anti-busing movement’s loudest voice, a conservative group called Restore Our Alienated Rights led by Hicks, held a massive protest at Government Center. The crowd jeered and threw tomatoes and eggs at Senator Ted Kennedy, a busing supporter. He tried to calm them down. Instead, he was chased inside the building.

A protester called him a

Another shouted,

Days before the start of the new school year, the anti-busing movement’s loudest voice, a conservative group called Restore Our Alienated Rights led by Hicks, held a massive protest at Government Center. The crowd jeered and threw tomatoes and eggs at Senator Ted Kennedy, a busing supporter. He tried to calm them down. Instead, he was chased inside the building.

A protester called him a

Another shouted,

Days before the start of the new school year, the anti-busing movement’s loudest voice, a conservative group called Restore Our Alienated Rights led by Hicks, held a massive protest at Government Center. The crowd jeered and threw tomatoes and eggs at Senator Ted Kennedy, a busing supporter. He tried to calm them down. Instead, he was chased inside the building.

A protester called him a

Another shouted,

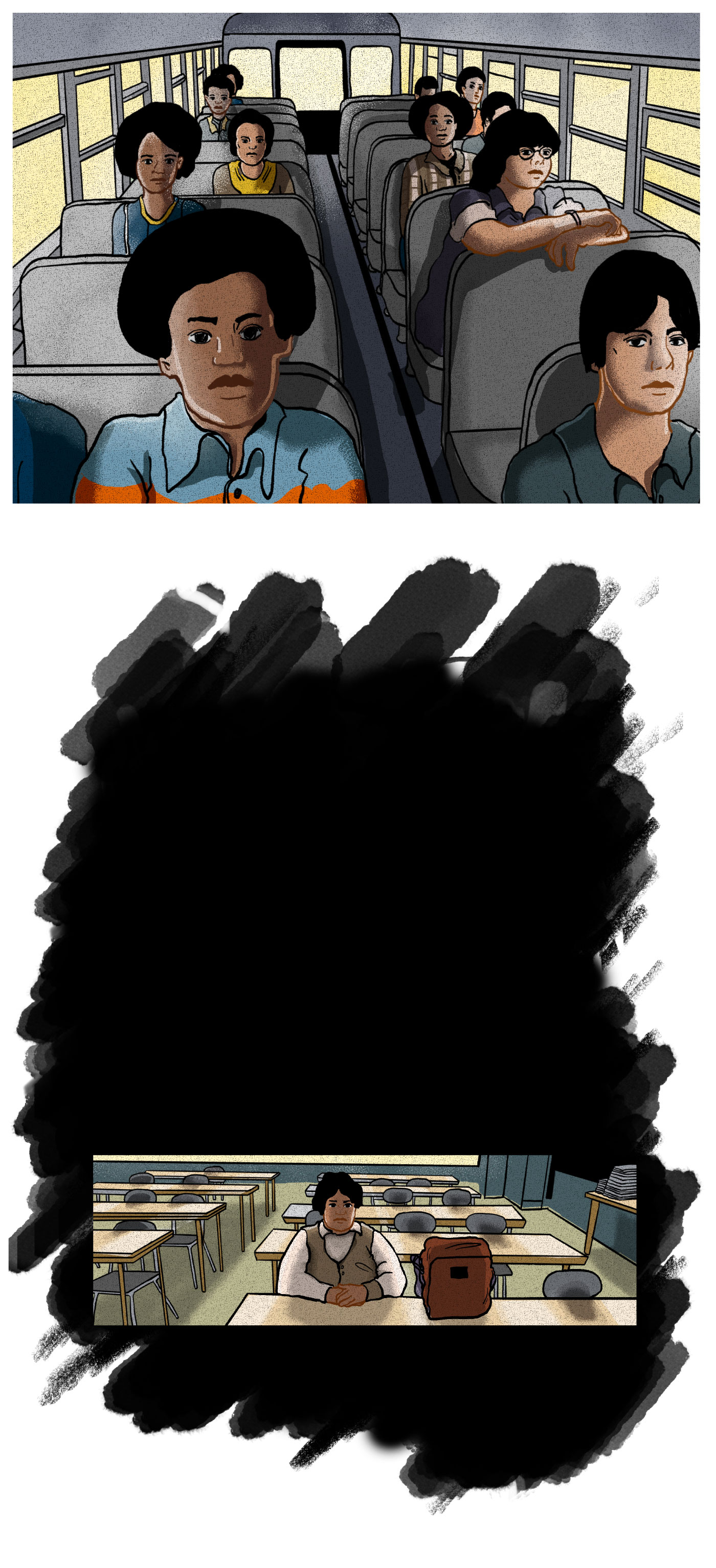

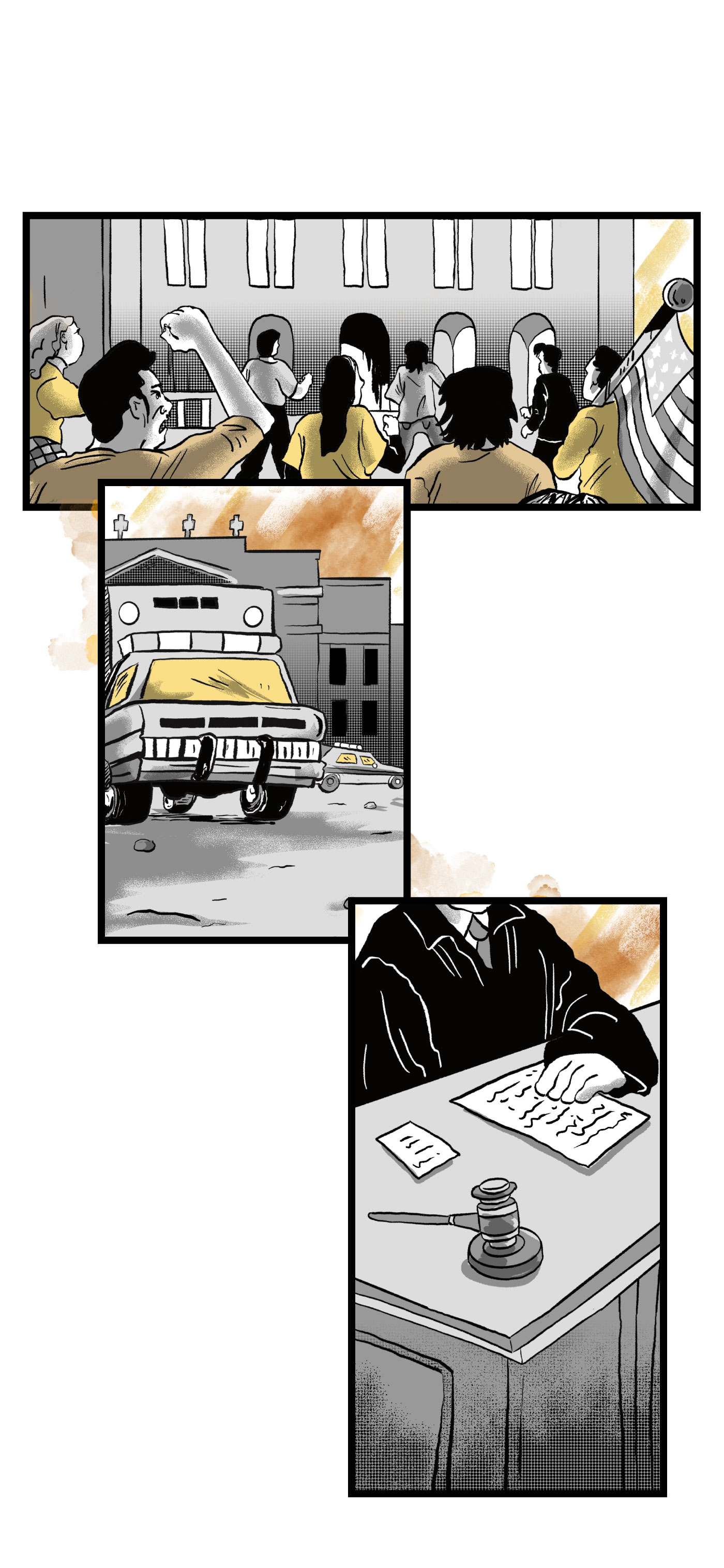

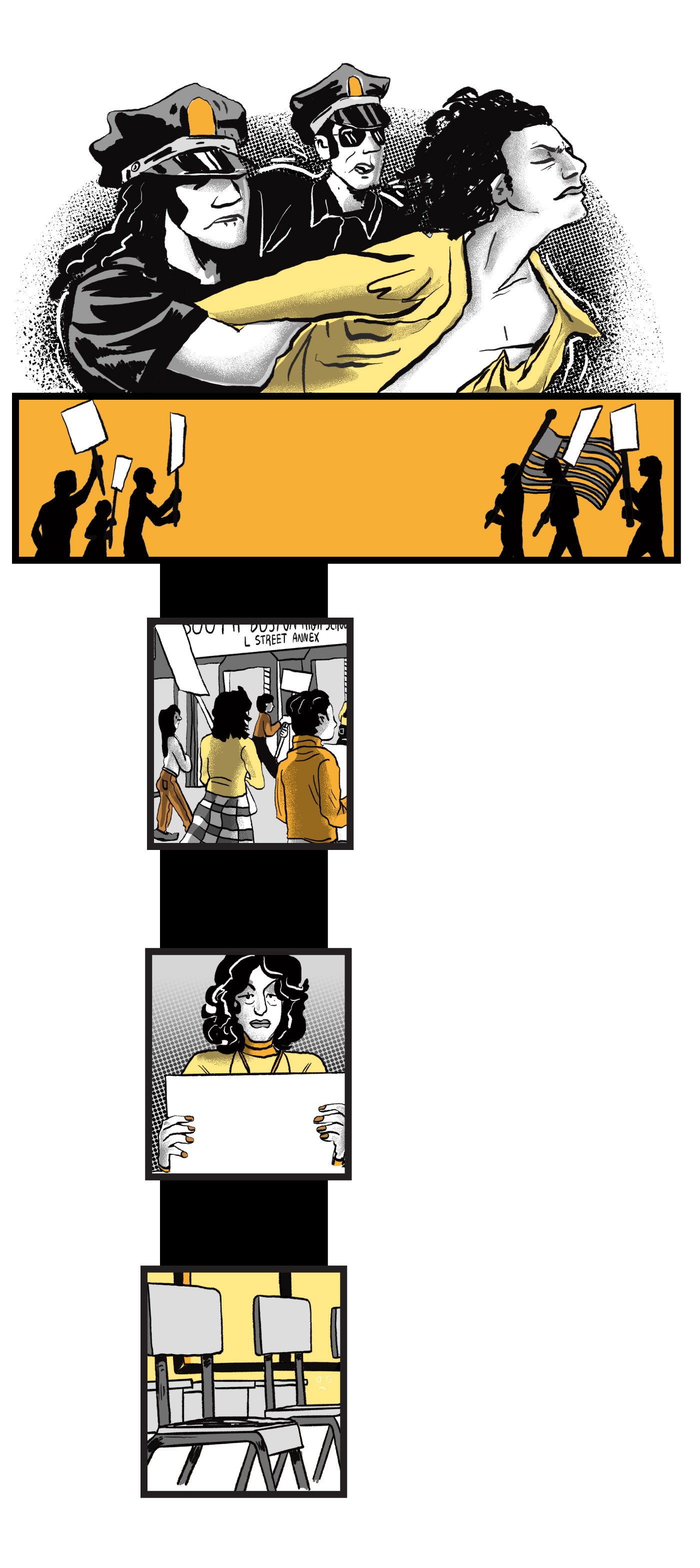

The new school year began on Sept. 12, 1974. Roughly half of the students at South Boston High and the William Bradford Annex School in Dorchester were absent. At Roxbury High, only 20 white students showed up. That day, hundreds of white protesters descended on South Boston High, where they hurled rocks and yelled slurs at the Black students arriving by bus. Eight Black students and one Black bus monitor were injured.

VIolence and protests continued to erupt across the city…

The new school year began on Sept. 12, 1974. Roughly half of the students at South Boston High and the William Bradford Annex School in Dorchester were absent. At Roxbury High, only 20 white students showed up. That day, hundreds of white protesters descended on South Boston High, where they hurled rocks and yelled slurs at the Black students arriving by bus. Eight Black students and one Black bus monitor were injured.

VIolence and protests continued to erupt across the city…

The new school year began on Sept. 12, 1974. Roughly half of the students at South Boston High and the William Bradford Annex School in Dorchester were absent. At Roxbury High, only 20 white students showed up. That day, hundreds of white protesters descended on South Boston High, where they hurled rocks and yelled slurs at the Black students arriving by bus. Eight Black students and one Black bus monitor were injured.

VIolence and protests continued to erupt across the city…

On Sept. 16, 300 white youths stormed the Andrew Square MBTA station, assaulting Black students, tearing out pay phones, and flipping over benches.

On Sept. 19, white and Black students got in a fight in the cafeteria at Hyde Park High School, leaving four students injured.

That same day, a bullet tore through the front door of Jamaica Plain High School.

David Duke, leader of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, showed up in South Boston “to help whites fight the tyranny of busing their children into the black ghetto.”

Three days later, a 200-car motorcade of anti-busing demonstrators converged outside the Boston Globe offices to protest both busing and the newspaper’s coverage of it.

On Sept. 16, 300 white youths stormed the Andrew Square MBTA station, assaulting Black students, tearing out pay phones, and flipping over benches.

On Sept. 19, white and Black students got in a fight in the cafeteria at Hyde Park High School, leaving four students injured.

That same day, a bullet tore through the front door of Jamaica Plain High School.

David Duke, leader of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, showed up in South Boston “to help whites fight the tyranny of busing their children into the black ghetto.”

Three days later, a 200-car motorcade of anti-busing demonstrators converged outside the Boston Globe offices to protest both busing and the newspaper’s coverage of it.

On Sept. 16, 300 white youths stormed the Andrew Square MBTA station, assaulting Black students, tearing out pay phones, and flipping over benches.

On Sept. 19, white and Black students got in a fight in the cafeteria at Hyde Park High School, leaving four students injured.

That same day, a bullet tore through the front door of Jamaica Plain High School.

David Duke, leader of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, showed up in South Boston “to help whites fight the tyranny of busing their children into the black ghetto.”

Three days later, a 200-car motorcade of anti-busing demonstrators converged outside the Boston Globe offices to protest both busing and the newspaper’s coverage of it.

On Oct. 6, anti-busing protesters descended on the Boston Police Department headquarters, demanding the department withdraw the patrol force assigned to protect Black students in South Boston as they arrived at and exited school.

A week later, seven white students and a white teacher were seriously injured in a series of fights at Hyde Park High School, including a 15-year-old boy who was stabbed in the gut.

On October 31, Garrity ordered the School Committee to submit the second phase of its desegregation plan for implementation in September 1975. The order required the School Committee to provide “other minority students,” including Asian Americans and Latinos, a desegregated education.

On Oct. 6, anti-busing protesters descended on the Boston Police Department headquarters, demanding the department withdraw the patrol force assigned to protect Black students in South Boston as they arrived at and exited school.

A week later, seven white students and a white teacher were seriously injured in a series of fights at Hyde Park High School, including a 15-year-old boy who was stabbed in the gut.

On October 31, Garrity ordered the School Committee to submit the second phase of its desegregation plan for implementation in September 1975. The order required the School Committee to provide “other minority students,” including Asian Americans and Latinos, a desegregated education.

On Oct. 6, anti-busing protesters descended on the Boston Police Department headquarters, demanding the department withdraw the patrol force assigned to protect Black students in South Boston as they arrived at and exited school.

A week later, seven white students and a white teacher were seriously injured in a series of fights at Hyde Park High School, including a 15-year-old boy who was stabbed in the gut.

On October 31, Garrity ordered the School Committee to submit the second phase of its desegregation plan for implementation in September 1975. The order required the School Committee to provide “other minority students,” including Asian Americans and Latinos, a desegregated education.

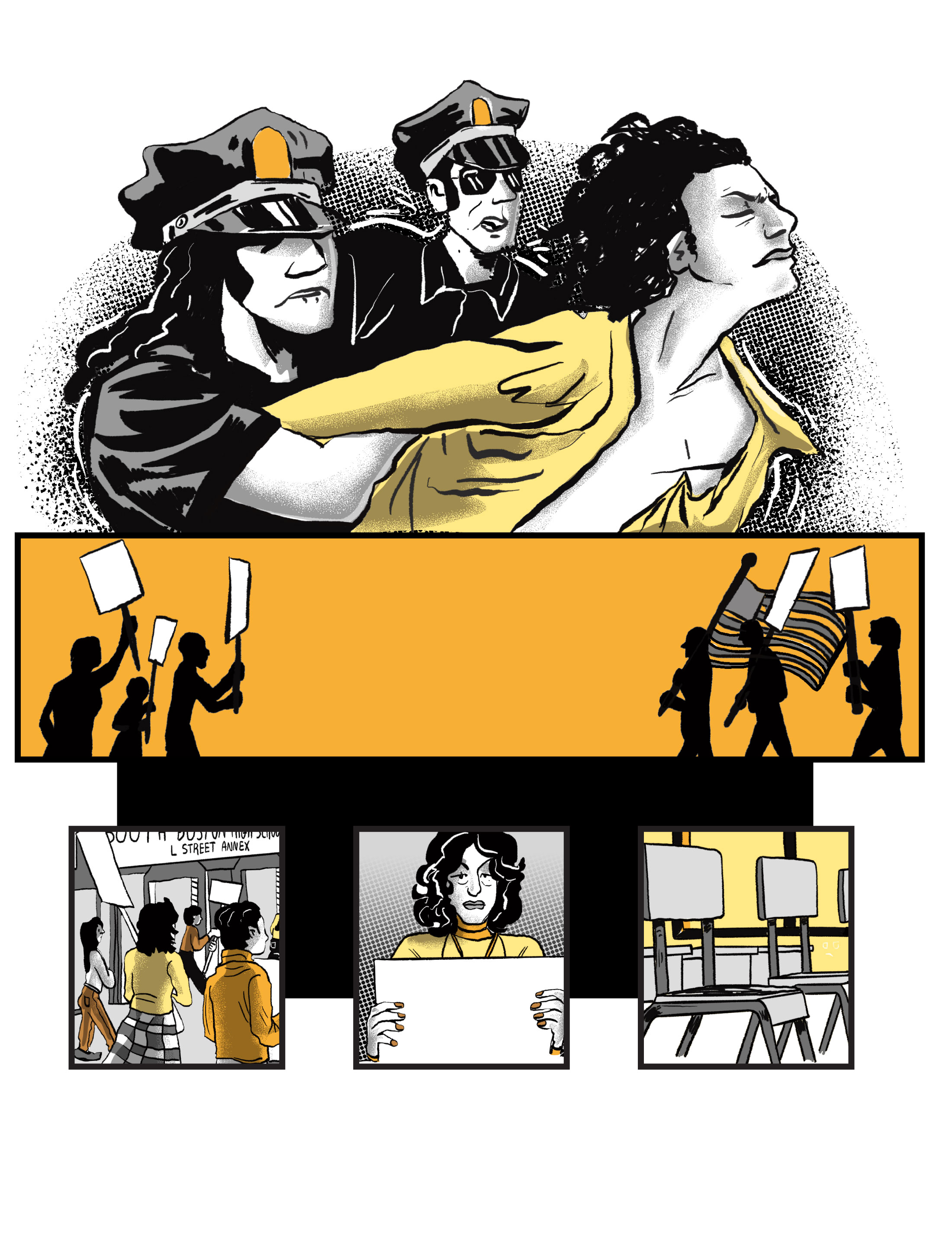

Throughout November and December, violence and protests persisted…

On Nov. 5, nearly all of the white students refused to show up at South Boston High.

On Nov, 25, the majority of Boston’s white students were absent from school.

On Nov. 24, Elvira “Pixie” Palladino led a 4,000-person anti-busing protest in East Boston.

Throughout November and December, violence and protests persisted…

On Nov. 5, nearly all of the white students refused to show up at South Boston High.

On Nov. 24, Elvira “Pixie” Palladino led a 4,000-person anti-busing protest in East Boston.

On Nov, 25, the majority of Boston’s white students were absent from school.

Throughout November and December, violence and protests persisted…

On Nov. 5, nearly all of the white students refused to show up at South Boston High.

On Nov. 24, Elvira “Pixie” Palladino led a 4,000-person anti-busing protest in East Boston.

On Nov, 25, the majority of Boston’s white students were absent from school.

On Nov. 30, Coretta Scott King led a 5,000-person pro-integration march from Boston Common to City Hall Plaza.

By the end of 1974, an estimated 15 percent of white students had abandoned BPS for private schools and other districts.

On Nov. 30, Coretta Scott King led a 5,000-person pro-integration march from Boston Common to City Hall Plaza.

By the end of 1974, an estimated 15 percent of white students had abandoned BPS for private schools and other districts.

On Nov. 30, Coretta Scott King led a 5,000-person pro-integration march from Boston Common to City Hall Plaza.

By the end of 1974, an estimated 15 percent of white students had abandoned BPS for private schools and other districts.

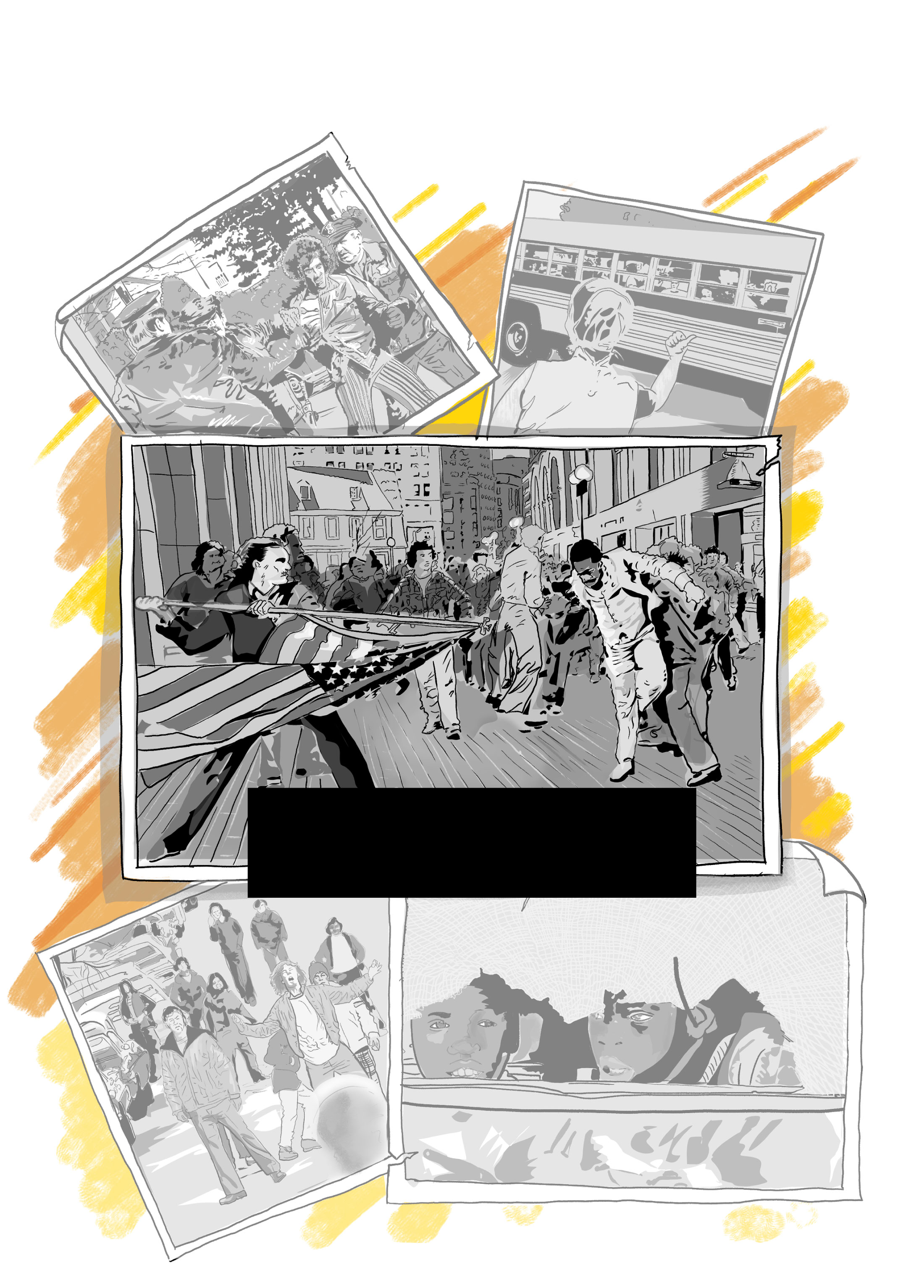

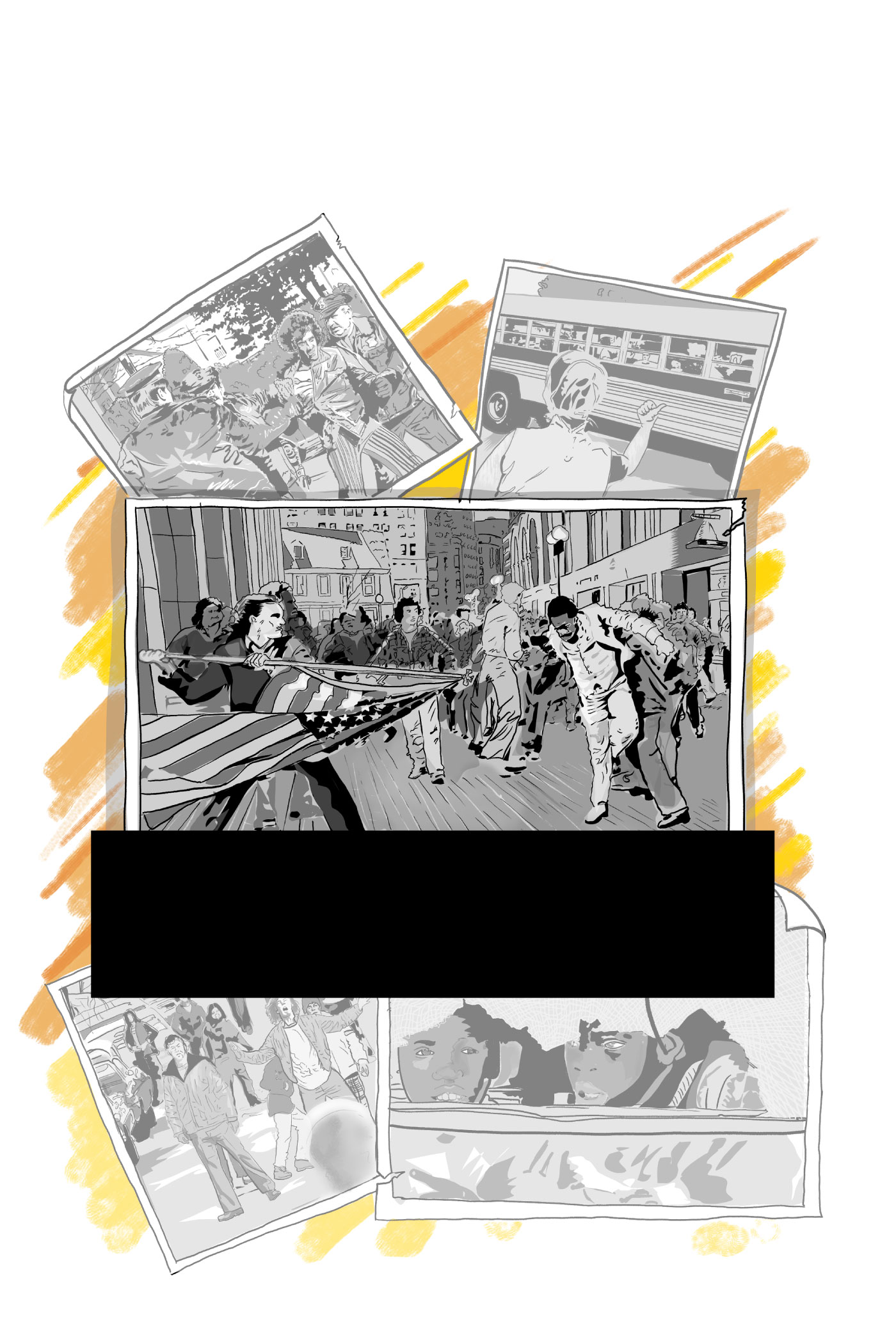

In the years immediately following Garrity’s order, anti-busing tension and violence flared across Boston, making national headlines as the city’s “busing crisis.”

A photograph by a Boston Herald American photographer called “The Soiling of Old Glory,” taken on April 5, 1976, emerged as a poignant symbol of the city’s anti-Black racism.

In the years immediately following Garrity’s order, anti-busing tension and violence flared across Boston, making national headlines as the city’s “busing crisis.”

A photograph by a Boston Herald American photographer called “The Soiling of Old Glory,” taken on April 5, 1976, emerged as a poignant symbol of the city’s anti-Black racism.

In the years immediately following Garrity’s order, anti-busing tension and violence flared across Boston, making national headlines as the city’s “busing crisis.”

A photograph by a Boston Herald American photographer called “The Soiling of Old Glory,” taken on April 5, 1976, emerged as a poignant symbol of the city’s anti-Black racism.

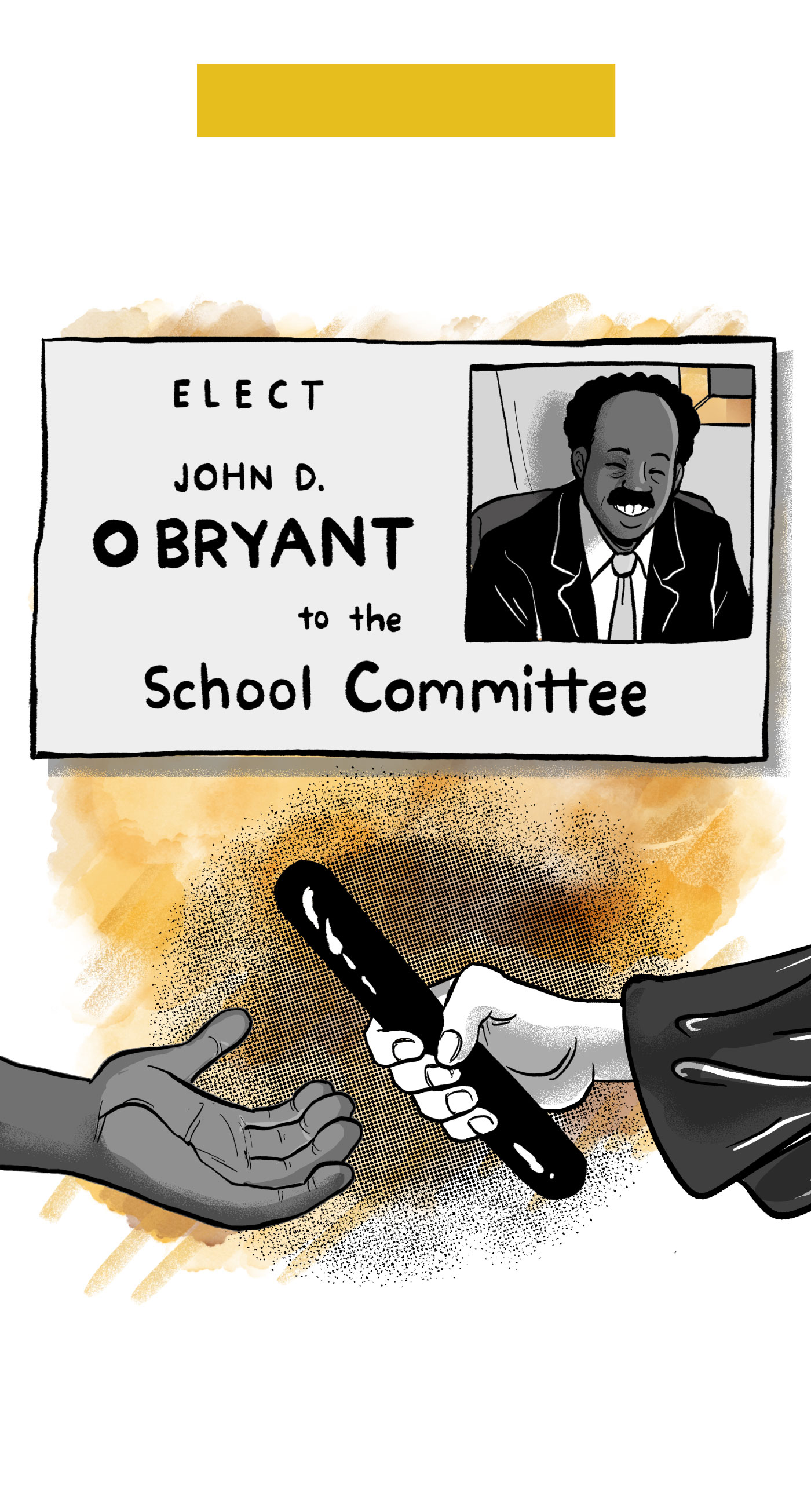

But there were signs of progress…

In 1977, John O'Bryant was elected to the Boston School Committee, its first Black member since 1895.

By 1982, Garrity had turned over day-to-day monitoring of Boston’s desegregation efforts to the state Board of Education.

But there were signs of progress…

In 1977, John O'Bryant was elected to the Boston School Committee, its first Black member since 1895.

By 1982, Garrity had turned over day-to-day monitoring of Boston’s desegregation efforts to the state Board of Education.

But there were signs of progress…

In 1977, John O'Bryant was elected to the Boston School Committee, its first Black member since 1895.

By 1982, Garrity had turned over day-to-day monitoring of Boston’s desegregation efforts to the state Board of Education.

Garrity issued his final desegregation order in 1985. And that year, Laval S. Wilson was selected as Boston’s first Black superintendent.

In 1987, a federal appeals court concluded the district’s schools were as “desegregated as possible given the realities of modern urban life,” clearing the way for the city to develop its own student assignment plan.

Garrity issued his final desegregation order in 1985. And that year, Laval S. Wilson was selected as Boston’s first Black superintendent.

In 1987, a federal appeals court concluded the district’s schools were as “desegregated as possible given the realities of modern urban life,” clearing the way for the city to develop its own student assignment plan.

Garrity issued his final desegregation order in 1985. And that year, Laval S. Wilson was selected as Boston’s first Black superintendent.

In 1987, a federal appeals court concluded the district’s schools were as “desegregated as possible given the realities of modern urban life,” clearing the way for the city to develop its own student assignment plan.

Fifty years after the Garrity decision, Boston’s proportion of white residents has shrunk due to decades of white flight to the suburbs — a phenomenon hastened by busing. In 1970, about 80 percent of Boston residents were white; now the city is 47 percent white. Just 15 percent of the district’s enrollment is white, down from 64 percent in 1970.

BPS no longer considers race and ethnicity when assigning students to schools, but students are still being bused today. Researchers have found that busing provides little academic benefit to Black and Latino students.

Boston schools serving predominantly Black and Latino students still underperform schools with higher proportions of white and Asian American students. While attendance and graduation rates among Black students are higher today than they were in the 1970s, the dream of an equal education for all still has not been achieved…

Fifty years after the Garrity decision, Boston’s proportion of white residents has shrunk due to decades of white flight to the suburbs — a phenomenon hastened by busing. In 1970, about 80 percent of Boston residents were white; now the city is 47 percent white. Just 15 percent of the district’s enrollment is white, down from 64 percent in 1970.

BPS no longer considers race and ethnicity when assigning students to schools, but students are still being bused today. Researchers have found that busing provides little academic benefit to Black and Latino students.

Boston schools serving predominantly Black and Latino students still underperform schools with higher proportions of white and Asian American students. While attendance and graduation rates among Black students are higher today than they were in the 1970s, the dream of an equal education for all still has not been achieved…

Fifty years after the Garrity decision, Boston’s proportion of white residents has shrunk due to decades of white flight to the suburbs — a phenomenon hastened by busing. In 1970, about 80 percent of Boston residents were white; now the city is 47 percent white. Just 15 percent of the district’s enrollment is white, down from 64 percent in 1970.

BPS no longer considers race and ethnicity when assigning students to schools, but students are still being bused today. Researchers have found that busing provides little academic benefit to Black and Latino students.

Boston schools serving predominantly Black and Latino students still underperform schools with higher proportions of white and Asian American students. While attendance and graduation rates among Black students are higher today than they were in the 1970s, the dream of an equal education for all still has not been achieved…

This story was developed in collaboration with The Gutter Studios, a collective of visual storytellers from Boston University’s MFA in Visual Narrative.

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporter: Deanna Pan

- Cartoonists: Joel Christian Gill, Francis Bordeleau, Ella Scheuerell, Dajia Zhou, Sandeep Badal

- Editors: Melissa Barragán Taboada, Anica Butler, Christina Prignano

- Additional editors: Cristina Silva, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Stanley Forman, The Boston Herald-American, and Charles Dixon, Dan Sheehan, Phil Preston, Joe Dennehy, Paul Connell, Jack O’Connell, and David L. Ryan, Globe staff

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara, John Hancock

- Copy editors: Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Jenna Reyes, Adria Watson

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer, Adria Watson

- Homepage strategy: Peter Bailey-Wells

- Project lead: Melissa Barragán Taboada

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC