BROKEN PROMISES, UNFULFILLED HOPE

Inside the forgotten story of Chinatown mothers who mobilized during the Boston busing crisis

Editor’s note: A version of this story on the fight for better education among Boston’s Chinese American families was originally published Sept. 12, 2022.

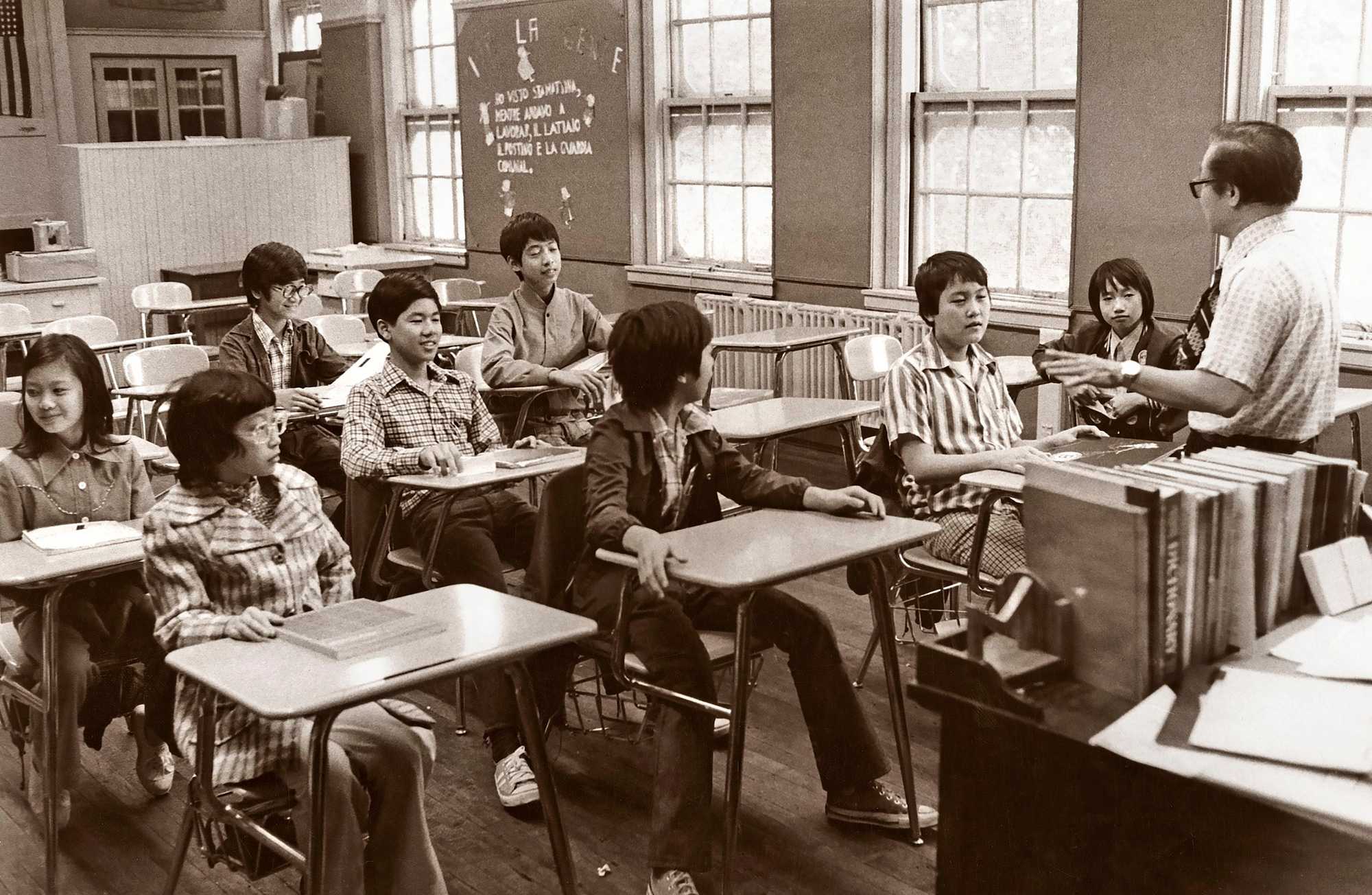

In the summer of 1975, Suzanne Lee was turning 25 and finishing her first year teaching bilingual education at the old Josiah Quincy School in Chinatown. History had been made a year earlier, when US District Court Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. found the Boston School Committee deliberately segregated city schools, igniting vicious resistance from those who opposed his remedy of busing Black and white children to schools in each others’ neighborhoods.

There was no mention in Garrity’s ruling of the students Lee taught — the children of poor Chinese immigrants who spoke little or no English, and worked as seamstresses, cooks, and busboys in Chinatown.

In the plan to desegregate Boston’s schools in the 1970s, other students of color were omitted and ignored by both the federal court and the School Committee, writer Michael Liu in his book, “Forever Struggle,” on the history of Boston’s Chinatown. “At best,” he wrote, Chinese students “were treated as pawns,” cast by white society as the “model minority” — quiet, compliant, and obedient — in order to disparage Black children.

The story of Boston’s busing crisis, the one memorialized in books, films, and podcasts, is typically characterized as a Black and white struggle. What is less known is the story Lee and her contemporaries remember — of the Chinese immigrant women who made history themselves. To ensure the safety of their children — who would also be bused to predominantly white schools — they organized a three-day school boycott in 1975 that would change the balance of power in Chinatown for decades to come.

“They didn’t do it for themselves,” said Lee, who went on to serve as principal of the Josiah Quincy School. “They did it for their children and their future — for their family.”

In the years preceding desegregation, Chinatown was at a crossroads. Developers had zeroed in on Chinatown, displacing hundreds of families with new highway construction and the expansion of Tufts-New England Medical Center. An influx of new immigrants also had moved into the neighborhood after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 abolished the national origin quota system.

May Moy was one of them, arriving in Boston with her family from Hong Kong in 1974. The Chinatown she remembers was dirty and dilapidated, with rampant crime and few social services. But Chinatown was still her family’s safe haven.

“All Chinese were welcomed,” Moy, now 82, explained through an interpreter.

Advertisement

But the rest of the city felt hostile.

“Sometimes,” she said, “you feel like they look at us as if we are here to take their position or take something away from them.”

Her first year in Boston was her hardest. She didn’t know any English, and neither did her children. Her son, who was 7 when they emigrated, was bullied at the Abraham Lincoln School in nearby Bay Village, where a fraction of the students were Chinese. He’d come home covered in bruises, Moy recalled. “I cried a lot,” she said.

By then, the first phase of the court-ordered desegregation had begun. Asian and Latino students made up as much as 7 percent of the district’s enrollment. In the fall of 1974, the Chinese community had avoided becoming a target of the violent protests engulfing predominantly white neighborhoods, where Black students were being bused. Under the state’s racial-balancing plan, more than 200 Chinese middle and high school students were bused out of Chinatown, including 174 to Michelangelo Middle School in the North End. White students and staff at Michelangelo were reportedly happy to have them, or at least they preferred them to Black children.

As one white North End mother told The Boston Globe during the first week of classes, “We don’t mind having the Chinese bused in — better than anybody else.” A white sixth grader was more direct about it: “Some are shy, but they’re mostly nice,” the boy said of the Chinese students, “and they don’t start any trouble like some of the black kids.”

The second phase of the desegregation plan was set to begin in September 1975 and would affect Chinatown’s elementary students, with approximately 1,000 set to be bused. In June, Chinatown parents received letters notifying them that their youngest children would be reassigned to schools outside of the neighborhood. But the letters were in English, which they couldn’t read.

“We didn’t know any of the details or any of the news,” recalled May Yu, now 91, speaking through an interpreter. “The only thing we had was the letter that our children would be going to a different school.”

That summer, Lee had volunteered to teach English classes on Saturdays at the old Quincy School. Her adult students were largely Chinese mothers, like Yu and Moy, who worked as seamstresses in the garment factories. A couple of mothers had approached Lee with their letters, and she agreed to organize a meeting explaining the contents to residents.

Advertisement

Lee and the mothers met weekly throughout the summer, forming the Boston Chinese Parents Association. Their ranks swiftly grew to the hundreds. They wrote letters about their concerns for their children’s safety to Garrity and school officials, but received no response. Eventually, they turned to the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, an influential, male-dominated group of local Chinese businessmen who often acted as intermediaries between Chinatown and the city leaders.

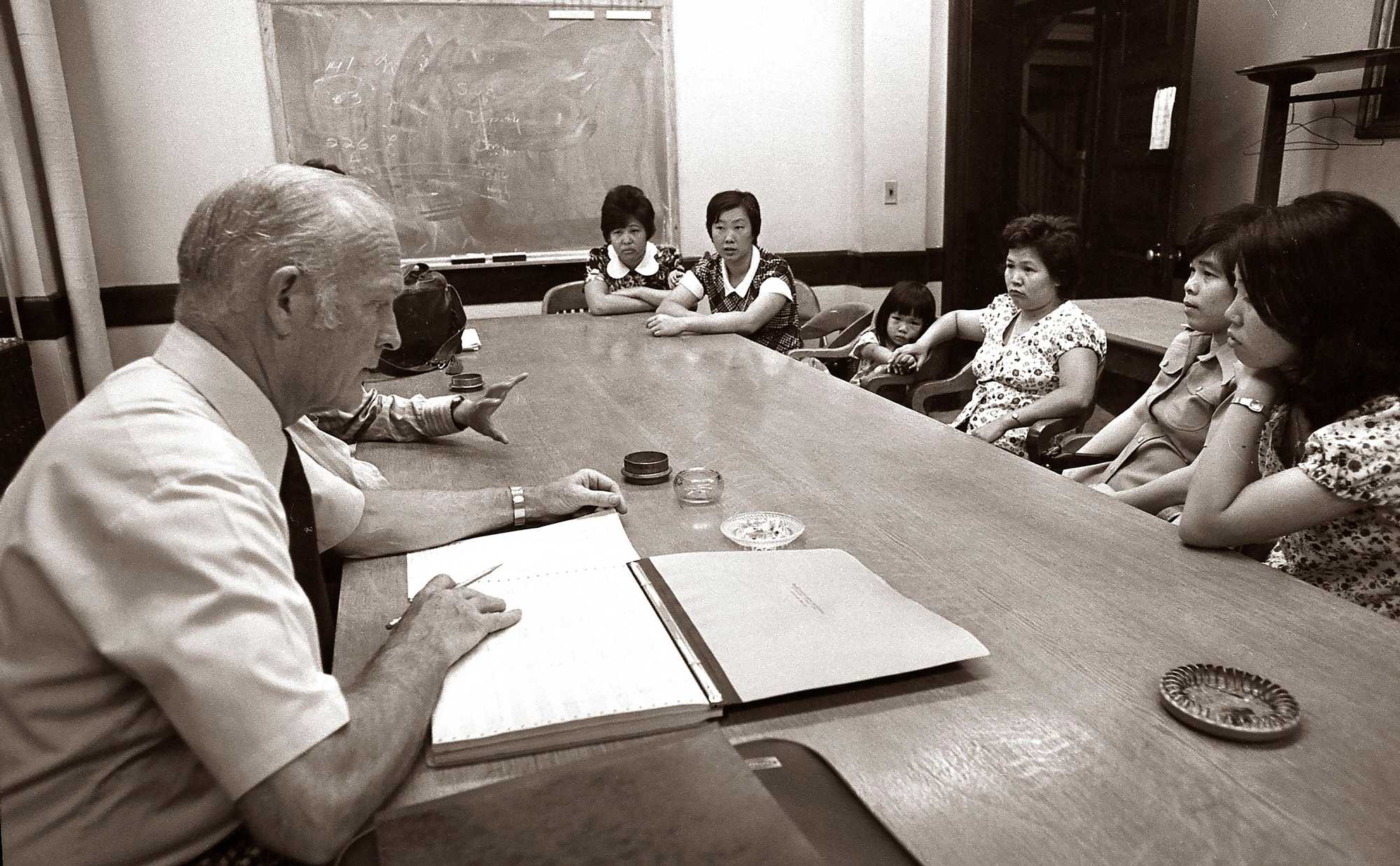

Moy was one of four mothers from the Boston Chinese Parents Association who met with the CCBA at the association’s Oxford Street office while hundreds of parents waited in an auditorium at Tufts’ Posner Hall. The mothers had hoped the CCBA could appeal to the School Committee. Instead, they were brusquely dismissed.

“They were yelling at us,” Moy recalled. “They said, ‘Why don’t you become president and chairman so you can take care of things like this? We don’t have time.’ ... There was no help at all.”

With no one to turn to but themselves, the parents started speaking out publicly. On July 30, 1975, they issued a list of nine demands to the Boston School Committee, with a request for response no later than Aug. 8.

Their demands included a minimum number of Chinese students, teachers, and aides at each of the schools where Chinese students were being reassigned. They wanted Chinese escorts on the buses transporting Chinese students, increased security at bus stops, and the hiring of staff who could communicate with the parents in Chinese.

The School Committee agreed to meet with some of the Chinese mothers on Aug. 6, with Lee serving as their interpreter. The mothers, in an interview with the Globe, praised three of the committee members “for being interested enough to ask questions and to talk to us about demands.” But two School Committee members, John Kerrigan and Paul Ellison, “whisper[ed] and snicker[ed]” the entire time, one mother said. “I want to know what they thought was so funny — the fact that we can’t speak English, that we’re Chinese?”

The School Committee made no promises. With the first day of school fast approaching, the Chinese parents threatened “severe actions” in the press. Finally, the night before the first day of classes, the parents voted unanimously to do something drastic and unprecedented — they would refuse to send their children to school.

The following morning, more than 90 percent of the Chinese students scheduled to be bused out of the neighborhood did not show up for class.

Lee, who had just returned from her honeymoon when she heard about the impending boycott, was flabbergasted at what the mothers had accomplished. She would be teaching fifth grade at the Harvard Kent School in Charlestown and had volunteered to serve as a bus monitor for students traveling from Chinatown to Charlestown. Not a single Chinese student boarded the bus, she said.

Advertisement

“[The mothers] probably called everyone that they knew at night and then they sent people to each bus stop to catch those people they weren’t able to talk to,” she said. “That took some organizing.”

Chinatown was buzzing with excitement, recalled Yu, whose children had been reassigned to the Harvard Kent School.

“Quite a few of us kept encouraging each other that we have to unite together and stand up until we feel like our children can be safe,�” she said.

The mothers had heard the stories in the news of white protesters hurling stones and bricks at buses full of Black students. “We didn’t want that to happen to our children,” Yu added.

When Lee reported to work, an urgent phone call from the US Department of Justice, which was overseeing the city’s desegregation effort, was waiting for her. Would Lee arrange a meeting with the Boston Chinese Parents Association, they asked?

The boycott continued for two more days before Lee and the parents met with an official from the Justice Department. Within half an hour, the official pledged to meet all of the parents’ demands, with the exception of hiring more Chinese teachers and aides, which was left to the teachers’ union to negotiate. As the meeting was concluding, the Justice Department staffer made an offhand comment to Lee that she would never forget: The schools needed the Chinese students to act as a “buffer” between the Black and white children.

“I was completely fuming inside,” Lee said. She couldn’t bring herself to translate the Justice Department’s message to the Chinese parents, who were celebrating their hard-fought victory. But the remarks stung because they reminded Lee about Asian Americans’ place in the nation’s racial hierarchy.

“This is what we are worth in the eyes of people who have power. They’re not concerned about getting kids back because they need education,” Lee said. “We are forever in their eyes just a wedge, we’re in between ... We are nobody until they need us for something.”

The next morning, the school buses to Charlestown and beyond were full of Chinese students. The parents’ boycott was a watershed moment for Chinatown’s working-class community, according to Liu. Many of the mothers involved in the Boston Chinese Parents Association would go on to organize Chinatown’s first rent strike at Tai Tung Village and fight for job retraining when the neighborhood garment shops closed. Liu and Lee became founding members of the Chinese Progressive Association, which, to this day, supports low-income immigrants in Chinatown.

“Initially, everybody ignored them,” Liu said. The boycott “changed the perception. It let [those in power] know that there’s a Chinese community and they need to be paid attention to.”

The Great Divide team explores educational inequality in Boston and statewide. Sign up to receive our newsletter, and send ideas and tips to [email protected].

Advertisement

Credits

- Reporters: Mike Damiano, Christopher Huffaker, Mandy McLaren, Deanna Pan, Ivy Scott, Milton Valencia, Tiana Woodard

- Contributors: Niki Griswold, Lisa Wangsness, Marcela García, Adrian Walker

- Editors: Melissa Barragán Taboada, Kris Hooks

- Additional editors: Anica Butler, Cristina Silva, Mark Morrow

- Visuals editor: Tim Rasmussen

- Photographers: Erin Clark, Suzanne Kreiter, Jessica Rinaldi, Lane Turner, Craig F. Walker, Jonathan Wiggs

- Director of Photography: Bill Greene

- Photo editor: Leanne Burden Seidel

- Photo archivist: Colby Cotter

- Video producers: Randy Vazquez, Olivia Yarvis

- Audio producers: Jesse Remedios, Scott Helman

- Design: Ryan Huddle

- Development: Daigo Fujiwara

- Digital editor: Christina Prignano

- Copy editors: Michael J. Bailey, Mary Creane

- Quality assurance: Nalini Dokula

- Audience: Cecilia Mazanec, Jenna Reyes, Adria Watson

- SEO strategy: Ronke Idowu Reeves

- Newsletters: Jacqué Palmer, Adria Watson

- Homepage strategy: Peter Bailey-Wells

- Project lead: Melissa Barragán Taboada

- Researcher: Jeremiah Manion

© 2025 Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC